Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Sober

Încărcat de

Daniel EhieduTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Sober

Încărcat de

Daniel EhieduDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The third term passed like a dream.

Every day after school, Rikyen would hurry home and do her chores at hyperspeed. Then it would be the exhilarating run to the Place, arriving breathless to find Jaja already waiting for her on the waterside. And then the spinning carousel of activity: swimming, climbing, stumbling upon, discovering, shouting, wondering, wandering, sometimes holding hands, eating baskets upon baskets of fruit. Some days flowed fast; some days passed slow, but there was always happiness and there was always Jaja, until Rikyen began to confuse which was which. At sunset she would leave him and reluctantly head home to a wondering mother, envying Jajas absolute freedom and the fact that he could spend the rest of his life in the Place if he wanted. She would do her homework by the light of the hurricane lamp and then wander outside to the edge of the village square. She would sit on her grandmothers chair and watch the antics of the playing children. A part of her knew that she was hoping that Jaja would show up, even though she knew that that wasnt going to happen. He had never come down to the village square as far as she could remember, but there was always a strange picture in her mindprobably imagined, she decidedof him with shorter dreadlocks and a rounder face, staring down at her from the where he clung to the back of a tall, beautiful woman who Rikyen could not actually remember ever seeing in real time. Still, she would sit in the chair and watch the other children, and many times she would wish her grandmother was still alive, because Jaja was a big, happy secret that begged to be given away, but she dare not tell anyone that she spent the highlight of her day at Outside Lake with the mad son of Amara the village witch. Only the old woman would have listened without her eyes widening in horror or without slapping Rikyen across the face. Perhaps her father would have listened to her, too, but Rikyen was a little afraid of Dogara. He was always so well, so quiet. Once, there had been a party in their househer own birthday, she remembered; Dogara always had them celebrated in grand styleand a lot of people had come. It had started off as a childrens affair, with chewing gum and chin-chin and Rikyen the celebrant in white kwois-kwois shoes, but by evening it had begun to degenerate into something else as the men returned from the farms and began to drift to drift toward

the source of loud music. Soon, the music was louder and the records were changed from Dan Maraya to Bob Marley. Dogara sent four muscular men to Mama Dikwat. One pair returned carrying a pot of roasted dog meat, the other an even larger pot of steaming burukutu. The women present retired to the kitchen to set about making pepper soup. The children, taking the hint, wandered off to play somewhere else. The men settled down for a night of what would forever after be little more than a hazy memory. Much later that night, Rikyen made her way across the sleeping village from Promises house to her own compound. The place was now quiet; the men had drunk hard and fast and had fallen asleep on benches and beneath tables. They would have to be up early for tomorrows work. Apart from an occasional mumbling or the low, undulating rumble that consisted of the individual snores that could only be expected from such a gathering, the courtyard was fairly quiet. All the women, her mother included, had deserted the compound. They would return in the morning to fetch their wincing men, and they would talk loudly and shake them roughly, sadistically make them suffer in their hangovers, showing no mercy after they had been forced to sleep alone last night. Rikyen picked her way among the drunk and snoring men, a bit light-headed from the strong, strong smell of burukutu that hung over the compound like spirits over a mass burial. The compound was lit liberally enough by the big moon, but her parent s house was dark inside. Rikyen hated the dark. She wished shed slept over at Promises house, but she had come back because otherwise she would have had to make the journey early the next morning to fill the water pots from the river before bathing and heading off to school, and she preferred to come back home now than in the harmattan seasons harsh pre-dawn cold, when the air would be so cold it would hurt to breathe. She considered going to one of the tenants in the compound and borrowing a lantern, but the two houses with lit windows belonged to bachelors; both were young farmers who would not miss the nights festivities for anything less than sex. Either they would e lying half-dead among the other bodies out in the courtyard, or they would have locked themselves in with a woman. Either way, it would be difficult for Rikyen to get them to come and give her a light. She decided to brave it. All she had to do was find her way to her room. She didnt think she would lie awake in the dark; she was so very tired, and the damned kwois-kwois

shoes were a curse on her feet (Oh, what if shed known the torture had only just begun?). She would be out cold before she hit the pillow, she reassured herself, took a deep breath, squared her shoulders and entered the dark, empty house. She stopped just in front of the doorway, loathe to close the door and abandon the moonlight outside, even though it didnt help much against the darkness. But she had to shut out the mosquitoes that were swarming weaving between the sleeping men. Drunk mosquitoes. Standing in the silver rectangle just inside the open door, still hesitating, she noticed a dull glow not far up ahead, little brighter than a dying ember. Someone had lit the hurricane lamp but had turned it very low. She could leave the door open and hurry to the lamp and raise it to a safe, blazing brightness before shutting herself in the house. A little relieved, she started toward the table. She was almost there when she stumbled over a pair of unseen legs. She emitted a small shriek as she staggered backward, tripped over her own feet and started to fall. She heard a grunt, scrambling movement, and then a large pair of hands grabbed her around the waist and steadied her. She was about to unleash another shriek when they let go. Careful, said a gruff, familiar voice. She squinted but she could not see him properly; her eyesight had already begin failing by then. She heard his knee joints crack as he stood up from the floor and she saw a tall shadow reach over and raise the brightness of the lamp to a comfortable glow. Her father was frowning down at her. He too, had been sleeping: his eyes were red and face looked rumpled, but otherwise he was perfectly normal. Where have you been? She told him, in a voice that had gone a little squeaky. He had never laid a hand on her, had always been gentle, and yet she was a bit scared of him. Thinking back many years later, she wondered if she had not been scared of him as much as she had been terrified of somehow annoying him, making him shout at her and beat her like the other fathers, cracking the perfect portrait of the father she so admired. Your mother would have been furious, Rikyen. It is late and you have school tomorrow. But he wouldnt tell on her. He never did. Even his small frown had already melted away and he was smiling slightly, smiling slightly at her frown.

Come on, now. Lets get you to bed. He had picked up the hurricane lamp and led her through the body-strewn parlor. There were men asleep in here too, though she noticed that the path to the table from the front door had been cleared. Standing by the bed, holding up the lamp, he smiled at her grimace as she pulled off the kwois-kwois shoes. She was the one who had said she had wanted them. I will be in the parlor, he told her. Anything you want, you call and I will come. She nodded as he tucked her into bed like a very small child. He left her bedroom door wide open, leaving the lamp shining brightly in the doorway. She always wondered how he knew she was afraid of the dark when her mother did not. Snuggled under the thick blanket, feeling a warm, sleepy pleasantness, she watched her father with half-closed eyes by the light of the lamp as he made his way back into the parlor, shut the front door and went back to his position on the floor, stopping all the while to push a fallen pillow under somebodys head, lift a person who had almost slid off back onto the couch, pull down anothers jelabia from where it had slid up to expose a mans bare buttocks. That was how Rikyen always remembered her father: a man bending to do small, infinite acts of kindness, surrounded by drunken men, stone-cold sober.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

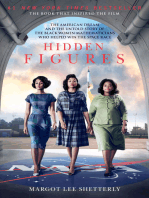

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- EFL Listeners' Strategy Development and Listening Problems: A Process-Based StudyDocument22 paginiEFL Listeners' Strategy Development and Listening Problems: A Process-Based StudyCom DigfulÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 кмжDocument6 pagini7 кмжGulzhaina KhabibovnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- OrderFlow Charts and Notes 19th Sept 17 - VtrenderDocument9 paginiOrderFlow Charts and Notes 19th Sept 17 - VtrenderSinghRaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modul9 VPNDocument34 paginiModul9 VPNDadang AbdurochmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Trial of Jesus ChristDocument10 paginiThe Trial of Jesus ChristTomaso Vialardi di Sandigliano100% (2)

- Green IguanaDocument31 paginiGreen IguanaM 'Athieq Al-GhiffariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Networking ProjectDocument11 paginiSocial Networking Projectapi-463256826Încă nu există evaluări

- Narrative of John 4:7-30 (MSG) : "Would You Give Me A Drink of Water?"Document1 paginăNarrative of John 4:7-30 (MSG) : "Would You Give Me A Drink of Water?"AdrianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vocabulary Words - 20.11Document2 paginiVocabulary Words - 20.11ravindra kumar AhirwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Signal&Systems - Lab Manual - 2021-1Document121 paginiSignal&Systems - Lab Manual - 2021-1telecom_numl8233Încă nu există evaluări

- Pesticides 2015 - Full BookDocument297 paginiPesticides 2015 - Full BookTushar Savaliya100% (1)

- NURS FPX 6021 Assessment 1 Concept MapDocument7 paginiNURS FPX 6021 Assessment 1 Concept MapCarolyn HarkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Garden Club of Virginia RestorationsDocument1 paginăGarden Club of Virginia RestorationsGarden Club of VirginiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Construction Agreement SimpleDocument3 paginiConstruction Agreement Simpleben_23100% (4)

- The Problem Between Teacher and Students: Name: Dinda Chintya Sinaga (2152121008) Astry Iswara Kelana Citra (2152121005)Document3 paginiThe Problem Between Teacher and Students: Name: Dinda Chintya Sinaga (2152121008) Astry Iswara Kelana Citra (2152121005)Astry Iswara Kelana CitraÎncă nu există evaluări

- PH Water On Stability PesticidesDocument6 paginiPH Water On Stability PesticidesMontoya AlidÎncă nu există evaluări

- 61 Point MeditationDocument16 pagini61 Point MeditationVarshaSutrave100% (1)

- Governance Whitepaper 3Document29 paginiGovernance Whitepaper 3Geraldo Geraldo Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- FFT SlidesDocument11 paginiFFT Slidessafu_117Încă nu există evaluări

- HUAWEI P8 Lite - Software Upgrade GuidelineDocument8 paginiHUAWEI P8 Lite - Software Upgrade GuidelineSedin HasanbasicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surefire Hellfighter Power Cord QuestionDocument3 paginiSurefire Hellfighter Power Cord QuestionPedro VianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BROADCAST Visual CultureDocument3 paginiBROADCAST Visual CultureDilgrace KaurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music 10: 1 Quarterly Assessment (Mapeh 10 Written Work)Document4 paginiMusic 10: 1 Quarterly Assessment (Mapeh 10 Written Work)Kate Mary50% (2)

- National Healthy Lifestyle ProgramDocument6 paginiNational Healthy Lifestyle Programmale nurseÎncă nu există evaluări

- HSE Induction Training 1687407986Document59 paginiHSE Induction Training 1687407986vishnuvarthanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Mercy Guided StudyDocument23 paginiA Mercy Guided StudyAnas HudsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mbtruck Accessories BrochureDocument69 paginiMbtruck Accessories BrochureJoel AgbekponouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Congestion AvoidanceDocument23 paginiCongestion AvoidanceTheIgor997Încă nu există evaluări

- Soul Winners' SecretsDocument98 paginiSoul Winners' Secretsmichael olajideÎncă nu există evaluări

- JurisprudenceDocument11 paginiJurisprudenceTamojit DasÎncă nu există evaluări