Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Meaning Is in The Eye of The Beholder

Încărcat de

AnneKPTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Meaning Is in The Eye of The Beholder

Încărcat de

AnneKPDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Running head: MEANING IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

Meaning is in the Eye of the Beholder Anne K. Przybysz Ohio University

MEANING IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER Many people believe that texts have a specific meaning regardless of the reader and the

readers knowledge and experiences; however, I encourage you to rethink this concept. Different people bring different backgrounds into reading a text and use their previous knowledge and experiences to gain an understanding of a text, especially when the text is difficult. People have different ways of trying to interpret a text, and some are better than others, allowing them to grasp a better understanding of complex ideas. In everyday life we see how gender and cultural differences affect communication between two people. These same differences can affect the meaning readers pull out of a text. Margaret Kantz, James E. Porter, Christina Haas and Linda Flower, Bill Bryson, and W. Ross Winterowd have all entered the conversation about rhetorical reading and have contributed their own thoughts. Kantz argued that students should think of facts as claims. She also argues that students need to develop an original argument and evaluate their resources; students should not only be summarizing and rephrasing their resources arguments. Porter challenges Kantz with his argument that no writing is truly original. Porter argues that all writing contains aspects of other writing in some way whether it be in topic, style, or grammar. Authors sometimes assume that their audience has previous knowledge about certain information, so they may not explain every piece of their text in detail. Haas and Flower added to the conversation by encouraging students to form their own hypotheses about the texts meaning and to make connections between different parts of the text as they read. Rhetorical reading involves understanding the texts purpose, context, and influence on the audience, and it also involves the readers using their previous knowledge and experiences to understand the text. Rhetorical reading requires readers to use their critical thinking skills when trying to interpret a text. Bryson joined the conversation in his analysis of the English language. Bryson argued that English

MEANING IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER develops as the meanings of words change over time; therefore, readers who understand the meaning of words in the past can bring that knowledge into reading a difficult text that uses the

older meanings of words. Winterowd entered into the conversation with his argument that writers put down their meaning on a piece of paper and readers have to draw the original meaning from the authors work. Various factors can affect the way people draw meanings out of texts. Societal views and norms can affect the way people interpret texts. How people define themselves in relation to their pasts and their families can also affect the way people interpret texts. People are progressively bought up from an early age to better read and understand the meanings behind texts. These tendencies that affect how well people read, understand, and interpret texts are best broken down into three categories: differences in gender, culture identification, and educational background. Gender differences can affect the way people interpret readings. In my sociology class last semester, the class discussed the different ways teachers treat their students based on being male or female. When males have a hard time understanding a topic they are encouraged to think it through and to come up with the correct answer. However, when females have a tough time understanding a concept the teacher tends to give them the correct answer; this may be one reason why both Haas and Flowers example student Kara and Kantzs example student Shirley performed subpar on the assignments they were given (Haas & Flower, 2011, p. 128; Kantz, 2011, p. 70). Male students are thought to be allowed to speak up while female students are thought to be quiet. Both of these gender differences give males an edge on being able to interpret challenging texts, so males are more likely to interpret complex reading material closer to an accepted interpretation by a teacher.

MEANING IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER Cultural differences play a role in the ways people decipher complex texts. People are taught to connect to various cultures from the time of their youth, and these connections to various cultures shape the ways they view the world. Many American families continue to connect with their original countries of origin, and these connections can affect the way people read texts. For example, a family that emigrated from England to the United States might be more inclined to believe Winston Churchills account of the Battle of Agincourt. In Kantzs article Helping Students Use Textual Sources Persuasively Kantzs character Shirley may be

more inclined to take details from Churchills account because it boosts about the English victory (Kantz, 2011, p. 71). At the same time, Shirley may be less willing to believe Guizot and Guizot de Witts account because they are trying to downplay the English victory (Kantz, 2011, p. 73). The two articles have different arguments about the events of the battle, and if a reader feels connected to one side over the other because of a cultural connection to a particular group, then that reader could pick out claims made from one side of an argument and ignore claims from the other side of an argument. Cultural differences such as language also have the potential to play into different interpretations of texts. As Bryson points out in his article Good English and Bad the English language is so complex that authorities of the language often get the phrasing wrong (Bryson, 1991, p. 45). Imagine a child brought up in an environment where proper English is seldom used; that child will probably receive a public education, but because of the improper use of language used around the child every day the child will not understand most of the proper English used in complex sources. Examples of these cultures that do not follow academic English are common; it may be more common to find cultures that speak improper English rather than proper English. These cultures and subcultures, such as cultures formed around the inner-cities and bi-lingual

MEANING IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER areas of the country, may assign meanings to words in texts different from the authors

intentions. Brysons example of the grammatically correct different from as opposed to the more commonly used different to or different than pales in comparison to cultures that drastically reshape the foundation of the English language (Bryson, 1991, p. 48). A persons educational level is normally a good indicator of how well a person interprets various texts. The American educational system begins to teach the fundamentals of reading to students in kindergarten. The educational system continues to teach students, with varying levels of success, skills needed for reading throughout every grade until graduation, first high school and then college. At the high school level students are expected to be able to point out reading devices such as introductory and concluding paragraphs, main points, and supporting evidence. In college the educational system expects students to be able to read texts more deeply and infer more claims from the readings. Haas and Flowers article Rhetorical Reading Strategies and the Construction of Meaning demonstrates this through one of its examples. The article points to a comparison of two summations of the introduction to a psychology textbook. The first summation, written by an undergraduate student, puts forward a vague idea about what the author of the sample piece meant and goes on to paraphrase the reading; however, the second summation, written by a Ph.D. student, did the same things as the first summation, with better wording in the response, and went on to include a hypothesis of the authors purpose and gives him a specific persona (Haas & Flower, 2011, p. 131). Haas and Flowers examples continually point out that an experienced or more educated reader draws more from texts than a less experienced or less educated reader. Haas and Flowers demonstrate that a more educated reader will get a deeper and wider variety of meaning from the texts that he or she reads.

MEANING IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER While there are instances when a persons educational status may not be the best predictor of his or her reading ability, these exceptions do not disprove the rule. A high school senior could be very motivated or receive some form of supplemental education that increases

his or her reading ability; transversely, a college student may seek only to get by and put minimal effort into doing his or her work. These and a variety of other factors can come into play, but the fact remains that the educational system expects more out of people the further up those people go inside the system. Haas and Flowers point that a more experienced, or better educated, reader is not contradicted by any kind of exception noted above. A part of the reason for the phenomena that Haas and Flowers article points out on the variability of readers educational level is found in Porters article Intertextuality and the Discourse Community. Theoretically, the higher a persons educational level the higher his or her number of readings over a lifetime. A typical high school student will not have read as many complex texts as a typical college graduate. The college graduate will have a greater degree of intertextuality (information from previous texts) to draw on when he or she needs to write about or interpret the meaning of any given text (Porter, 2011, pp. 88-89). The college graduate has a greater body of textual material in which to connect any given argument. If the educational system works properly, then at the time of the high school students graduation from college the high school student will possess a large body of texts in which to connect new material. W. Ross Winterowd in his article The Rhetorical Transaction of Reading asserts that The writer projects his meanings, intentions, and so forth onto the page (1976, p. 185). Winterowd further asserts that the reader has to reconstruct the authors original meaning (1976, p. 186). While an author certainly writes a piece of work with a specific meaning in mind, the readers purpose does not have to be the simple task of reconstructing the authors original

MEANING IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER intention. A reader can interpret events an author puts forward in a different light from what the

original author intended. A reader can impose his or her knowledge or preconceived notions onto an authors work, or that reader can identify and refute ideas put forth by the author. A part of the danger of Winterowds article is the notion that a reader can get the meaning of a text wrong. While some interpretations of texts may be better than others, the meaning people derive from texts always goes beyond the meaning the author intended for it. Despite peoples belief that a text has a specific meaning regardless of the reader, the truth is that a variety of factors direct how a person draws meaning out of a text. Gender and how society treats females differently from males, in American society at least, may account for some subpar performances for females in school. Cultural differences such as feeling connected to one group over another or varied and often improper language usage can affect the way a person accepts and rejects authors various claims and can even affect how much of a text the reader understands. The educational system attempts from its earliest stages to create better readers, but few people have the ability to go all the way up to the graduate school level; many people may not even make it past the high school level. No matter what a persons level of education, a higher education does not mean that readers will take a uniform meaning away from a text; readers with a higher education are simply more likely to draw more meaning from a given text. No matter what an authors intentions, it is difficult for a reader to read a piece of work wrong because a piece of literature means different things to different people. At the very least a reader should remember that if literature is like a pane of glass as Winterowd points to in his simile one of the images people see in a pane of glass is their own reflection (1976, p. 190). Literature and the meaning people derive from it is always personal and always a reflection of the reader.

MEANING IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER References: Bryson, B. (1991). Good english and bad. In The mother tongue: English & how it got that way (pp. 134-146). New York: Avon. Haas, C., & Flower, L. (2011). Rhetorical reading strategies and the construction of meaning.

In E. Wardle & D. Downs (Eds.), Writing about writing: A college reader (pp. 120-138). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martins. Kantz, M. (2011). Helping students use textual sources persuasively. In E. Wardle & D. Downs (Eds.), Writing about writing: A college reader (pp. 67-85). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martins. Porter, J. E. (2011). Intertextuality and the discourse community. In E. Wardle & D. Downs (Eds.), Writing about writing: A college reader (pp. 86-100). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martins. Winterowd, W. R. (1976). The rhetorical transaction of reading. College Composition and Communication, 27(3), 185-191.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- A Shorter Course in English Grammar and Composition (1880) PDFDocument200 paginiA Shorter Course in English Grammar and Composition (1880) PDFfer75367% (3)

- Porgy and Bess Student Study Guide PDFDocument20 paginiPorgy and Bess Student Study Guide PDFdorje@blueyonder.co.uk100% (2)

- Abhilasha AshtakamDocument5 paginiAbhilasha AshtakamSasidharan RakeshÎncă nu există evaluări

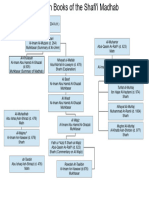

- Main Books of Shafii Madhhab ChartDocument1 paginăMain Books of Shafii Madhhab ChartM. A.Încă nu există evaluări

- Gayatri in English - Twelfth Part of The Third Chapter of Chandogya Upanishad in English With The Original Texts, Meanings, Etymology and Inner Meanings. Consciousness and The Universe.Document29 paginiGayatri in English - Twelfth Part of The Third Chapter of Chandogya Upanishad in English With The Original Texts, Meanings, Etymology and Inner Meanings. Consciousness and The Universe.Debkumar LahiriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pride and Prejudice Volume 1 Discussion QuestionsDocument2 paginiPride and Prejudice Volume 1 Discussion QuestionsMazen JaberÎncă nu există evaluări

- Talent Level 3 Table of ContentsDocument2 paginiTalent Level 3 Table of ContentsfatalwolfÎncă nu există evaluări

- Atherton The House of PowerDocument5 paginiAtherton The House of PowerJared MoyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Narrative TextDocument1 paginăNarrative TextMayRoseLazoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1st MaterialsDocument27 pagini1st MaterialsJeraheel Almocera Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treasure Island Chapter 23Document11 paginiTreasure Island Chapter 23Ahsan SaleemÎncă nu există evaluări

- 32IJELS 109202043 Oedipal PDFDocument3 pagini32IJELS 109202043 Oedipal PDFIJELS Research JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anand The UntouchableDocument3 paginiAnand The UntouchableArnab Mukherjee100% (1)

- Critique On Dead Poets SocietyDocument6 paginiCritique On Dead Poets SocietyMary Ann Medel100% (1)

- Erickson Ib Lit Course Outline 2020Document2 paginiErickson Ib Lit Course Outline 2020api-234707664Încă nu există evaluări

- CTSA 6-8 A Millerd The OutsidersDocument3 paginiCTSA 6-8 A Millerd The OutsidersMohammed WafirÎncă nu există evaluări

- SOAL UTS 1 BASA JAWA KELAS XIDocument7 paginiSOAL UTS 1 BASA JAWA KELAS XIUmu ChabibahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ueber Andronik Rhodos PDFDocument83 paginiUeber Andronik Rhodos PDFvitalitas_1Încă nu există evaluări

- Literary Section English Language Notes for Third Secondary Literary 2013/2014Document43 paginiLiterary Section English Language Notes for Third Secondary Literary 2013/2014kareemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marvel Previews 005 (December 2015 For February 2016)Document114 paginiMarvel Previews 005 (December 2015 For February 2016)Dante IrreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pilgrigmage ND TemplesDocument4 paginiPilgrigmage ND TemplesRajendra KshetriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coffee Table Book Submission Paritosh SharmaDocument17 paginiCoffee Table Book Submission Paritosh SharmaPARITOSH SHARMAÎncă nu există evaluări

- ConfessionsDocument9 paginiConfessionsNaveen Lankadasari100% (3)

- Socratic Circles Handout: The Chrysalids Novel StudyDocument1 paginăSocratic Circles Handout: The Chrysalids Novel Studyascd_msvu67% (3)

- The Sevenfold Spirit of GodDocument18 paginiThe Sevenfold Spirit of GodSuma Stephen100% (1)

- Capítulo: Santi y BelénDocument5 paginiCapítulo: Santi y BelénLorena ZentiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rancangan Semester English NewDocument4 paginiRancangan Semester English NewNormazwan Aini MahmoodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kenneth CopelandDocument18 paginiKenneth CopelandAnonymous 40zhRk1100% (1)

- The Moon That Embrace The SunDocument36 paginiThe Moon That Embrace The SunNorma PuspitaÎncă nu există evaluări