Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Journalism in A Network Society

Încărcat de

Mindy McAdamsTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Journalism in A Network Society

Încărcat de

Mindy McAdamsDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

This

introduction to the topic Journalism in a network society was written on request for the 3rd World Journalism Education Congress, Mechelen, Belgium, July 2013. http://wjec.be/

Introduction Text Syndicates WJEC-3

(this information will be published on www.wjec.be)

Syndicate number (1a -> 6c) Syndicate theme Author - Name Author - Organisation Author e-mail address 10 keywords introduction text

5a Journalism in a network society Mindy McAdams University of Florida - Gainesville, Florida, USA mmcadams@jou.ufl.edu network, society, social, political, economic, organization, power,

The phrase the network society refers to the conditions in which we live today. Like the information age or the industrial age, the phrase attempts to sum up a time in human history that is characterized by great changes in the way many people live in the world, setting this era apart from previous eras. Characteristics and effects of the network society are not limited to the developed nations. In the 1990s, two books devoted to exploring the idea of the network society were published in English: The Rise of the Network Society (1996), by Manuel Castells, and The Network Society (1999), by Jan van Dijk. (The latter was first published in Dutch in 1991, under the title De Netwerkmaatschappij.) Most references to the network society cite one or both of those books. In this paper, I will first present some basic definitions of the network society. Then I will outline some connections between ideas about the network society and the field of journalism. Finally, I will discuss some themes that journalism educators might include in their courses. 1. Network Society: Definitions Let us consider some broad definitions at the outset. A network society is a society whose social structure is made of networks powered by microelectronics-based information and communication technologies. By social structure I understand the organizational arrangements of humans in relationships of production, consumption, reproduction, experience, and power expressed in meaningful communication

coded by culture. A network is a set of interconnected nodes. A node is the point where the curve intersects itself. A network has no center, just nodes. (Castells, 2004a, p. 3) Van Dijk (2012) describes the network society as: A modern type of society with an infrastructure of social and media networks that characterizes its mode of organization at every level: individual, group/organizational and societal. Increasingly, these networks link every unit or part of this society (individuals, group and organizations). In western societies, the individual linked by networks is becoming the basic unit of the network society. In eastern societies, this might still be the group (family, community, work team) linked by networks. (p. 22) Van Dijk compares the network society and mass society, saying the latter had an infrastructure of groups, organizations and communities. The basic units of mass society, then, are or were relatively large collectives (p. 22), such as a mass audience. Castells (1996) discusses the end of the mass audience in chapter five. In a brief book exploring mostly Castells ideas, Darin Barney (2004) writes: The phrase network society applies to societies that exhibit two fundamental characteristics. The first is the presence in those societies of sophisticatedalmost exclusively digital technologies of networked communication and information management/distribution The second, arguably more intriguing, characteristic of network societies is the reproduction and institutionalization throughout (and between) those societies of networks as the basic form of human organization and relationship across a wide range of social, political and economic configurations and associations. (pp. 2526) Networks are made of nodes, ties and flows: A node is a distinct point connected to at least one other point, though it often simultaneously acts as a point of connection between two or more other points. A tie connects one node to another. Flows are what pass between and through nodes along ties. To illustrate, we might consider a group of friends as a network: each friend is a node, connected to at least one other friend but typically to many others who are also connected, both independently and through one another; the regular contacts between these friends, either in speech or other activities, whether immediate or mediated by a technology, are the ties that connect them; that which passes between themgossip, camaraderie, support, love, aidare flows. (Barney, 2004, p. 26) Barney (2004, pp. 525) discusses the relationship of the network society concept to post-industrialism, the information society, post-Fordism, postmodernism and globalization. As a society transitions from a manufacturing economy, where factories and tangible products form the basis of wealth, to a knowledge economy in which service industries such as finance, retail and recreation dominate, power and wealth depend more and more on access to and control of information.

The economic base of the network society is information, not industry. The network society is a global (or transnational) phenomenon that absorbs nation-states, weakening but not destroying them. All networks (social, cultural, political and economic) are both structuring (they make possible certain outcomes and prevent others) and highly flexible, able to expand or contract, grow new nodes or destroy old ones, often with breathtaking speed. Space and time are reconfigured by the flexibility of networks. The network society is always on and the placement of its members in territorial space is less important than their existence in the space of flows where crucial economic and other activity occurs. (Barney, 2004, p. 29) The network society is a phrase that indicates the connectedness of almost everything, globally and electronically. My country may have more nodes than your country, but all countries have nodes. Few societies on earth today are wholly outside the network. Some nodes have ties to only one or two other nodes, but there are no nodes that are completely cut off from all others. Without ties, a node is excluded from the network and ceases to be a node. Access to networks, and control over flows: These determine power in the network society. Access alone is not sufficient to confer power, but without access, one is powerless. [E]ntire regions or countries on the periphery of the global economy, or entire classes of people within the core itself, are effectively denied access and thereby excluded from crucial technological, economic, political and social networks. (Barney, 2004, p. 31) [T]he penalty for being outside the network increases with the networks growth because of the declining number of opportunities in reaching other elements outside the network. (Castells, 1996, p. 71) 2. The Network Society and the Journalism Field What does it mean for journalism to exist within a network society, to be enmeshed in such a system, in a world where communications are instant and asynchronous across oceans and continents? Observing the journalism field from this perspective invites us to consider how many connections (ties) there are between journalism institutions/actors and other nodes in various networks, and how timeless time and the space of flows affect the field. The word field calls to mind the work of Pierre Bourdieu. I have used it deliberately, because it encompasses all of these for any single field under discussion: A range of activities and products The people who do those activities and make those products The organizations (companies, firms, corporations) where those people work The history of all of those (activities, products, people, organizations) The laws, ethics and beliefs that govern all of those

So the field of journalism, encompassing its history and its people, the work and the products of that work, and so on, exists within the network societynot as a thing inside a bubble or a jar, sealed off from the rest of the world, but connected, as everything is connected. Madsen (2004) says the sociologies of Bourdieu and Castell do not immediately appear very comparable (p. 4)and then proceeds to weave them together, while noting strengths and weaknesses of each approach. As Madsen points out, a field and a network are constituted differently. The network society concept does not consider how an individual node (such as a reporter) functions within in a historical context; field theory accounts for a system of influences that affects individuals and institutions, and for how the autonomy of a field is increased or decreased by other fields. When we recognize journalism as a field, in Bourdieus sense of the word, we see clearly that journalism is not only products. It is not only corporations and media houses. Journalism is not only its mediums, such as television or print. Journalism comprises more than reporters, editors and other human actors. We can use the concept of the network society to understand what is happening to journalism, its products and the media houses. We can use it to understand how audiences are changing. We can consider the individual journalist as a node in a network (van der Haak et al., 2012). However, it is difficultperhaps impossibleto use the concept of the network society to understand journalism itself. For that, field theory is a better conceptual tool. Field theory works as a tool for studying both the micro-level practices of individual reporters (professional and amateur) and the macro-level institutional structures in which they invariably find themselves ... situated within a broader cultural, political and economic context (Compton and Benedetti, 2010, p. 488). The network society concept works as a tool for examining the effects of globalization on information flows, power that spans national borders, cultural products that invade other cultures. It works as a tool for examining the influences of multinational companies such as Google and Facebook. It works for examining structures that constrain and enable flows of capital and ideas. All of these can be applied to journalism studies. 3. How to Educate for Journalism in a Network Society These are several themes that journalism educators might want to include in their courses. a) Networking logic. Castells describes the new technological paradigm as having five central characteristics (1996, pp. 7072). One of these is networking logic, meaning that any system (or set of relationships) relying on information technology will be subject to both the benefits and constraints of networks, such as the ability to manage increasing complexity of interaction (p. 70). Ever-increasing microprocessor power means that humans literally can manage, process and analyze exponentially more data and more connections than was possible in the past, and at ever greater speeds. Data are infinitely sortable and infinitely combinable, enabling patterns to emerge that might never have been

discovered without digital technology. Thus networking logic enables not only movement of information but also the creation of new information based on making connections and finding patterns. Networking logic might be a useful idea in combination with teaching about data journalism: http://datajournalismhandbook.org/ And big data: http://journalistsresource.org/studies/economics/business/what-big-data-research-roundup b) Social media networks and journalism flows. One persons digitally enabled social network can be described using the words nodes, ties and flows. Journalism products (articles, videos, etc.) often enter these social flowsfor example, you share a link, and people in your social network might choose to open the link, comment about it, re-share it, etc. The activities of professional journalists in social networks (e.g., https://www.facebook.com/kristof) create direct ties between them and individual readers or viewers. Before the network society, people had social networks and kinship networks, but those networks never incorporated journalism like digital social networks do. c) Networked journalism. This is a practice that leverages networks to improve and expand journalists work and work products. In part, the journalist builds a network of collaborators (not merely sources) who are also part of the audience. Read more about it here: http://www2.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/POLIS/Files/networkedjournalism.pdf http://buzzmachine.com/2006/07/05/networked-journalism/ http://pressthink.org/2013/05/designs-for-a-networked-beat/ Includes: crowdsourcing, participatory journalism, citizen journalism, user-generated content. The actual product of journalistic practice now usually involves networks of various professionals and citizens collaborating, corroborating, correcting, and ultimately distilling the essence of the story that will be told. (van der Haak et al., 2012, p. 2927) d) Disaggregation of media products and audiences. When nodes and their ties to other nodes can be continually reconfigured, the mass is atomized, exploded into particles. That is disaggregation. A reader now reads news articles, not a newspaper, and can open items from many different publishers. A viewer now watches a video or an episode, not a television network. Members of a family watch individual screens, one per person. There is no need to share a copy of a newspaper. The items of journalism are now separated from the bundles or packages that used to bind them together. An important collateral effect is that journalism products are becoming less important to advertisers, who can command the screens of consumers attention without buying time or space from a journalism organization. e) Economics of journalism businesses. Financial support of journalism organizations and media houses varies from country to country. The BBC and its news operations, for example, are supported by license fees collected from all TV owners in the United Kingdom. In countries where the media houses are not

financed by the government or political parties, the disruption caused by audience migration to free online and mobile information sites has eroded revenues from both subscription fees and advertising. f) Transnational corporations and their role in helping or harming freedom of expression. Such corporations include Google and Facebook, which have a huge presence in so many different countries. A useful text on this topic is MacKinnon (2012). g) The network re-routes around censorship. This can be considered part of networking logic (see above) but warrants further attention in relation to transnational news flows. In the global network society, when a nation-states press and broadcast systems are controlled by the ruling political party, people with Internet access can get news reports from other countries. Language and other factors can be barriers. (The quote The Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it is attributed to Internet pioneer John Gilmore in the article First nation in cyberspace, by Philip Elmer-DeWitt, Time magazine, Dec. 3, 1993.) h) The space of flows vs. the space of places. Local journalism is centered in geographic space, but where is entertainment and celebrity journalism centered? If we compare journalism about where we live with journalism about professional sports and global celebrities, we can open a discussion about what the public needs to know vs. the news and information that the public desires. Castells space of flows also connects to important issues for journalism coverage, such as global manufacturing, trade and human capital, all related to transnational economics. i) Timeless time. The 24-hour/7-days operations of global markets are part of this, but how does 24/7 information affect the traditional news value of timeliness? We still see reporters racing to be first with a scoop (and sometimes making serious errors), but when does the audience for news actually value minute-by-minute updates? Young people who grew up with 24/7 information technology dont have the same attitude toward time and news, and journalists need to adjust their work routines accordingly. Castells (1996) refers to the timelessness of multimedias hypertext (p. 492), and I am reminded of my students reliance on being able to look up anything they need, whenever they need it. j) Real virtuality. Castells (1996) writes of all reality being captured and relayed to us through media. It brings to mind the Internet abbreviation IRL (in real life), used to specify that what is described is, in fact, real. Yes, we sometimes have to make that clear. One intersection with journalism is the increase in altered photographs appearing in respected publications. Does the audience trust journalism to be real? The phrase real virtuality might seem amusing at first glance, but its a genuine condition for young people who grew up with multiple screens. See: http://www.niemanlab.org/2011/04/photoshop-journalism-and-forensics-why-skepticism-may-be-the- best-filter-for-photojournalism/ The space of flows and timeless time are the material foundations of a new culture that transcends and includes the diversity of historically transmitted systems of representation: the culture of real virtuality where make-believe is belief in the making. (Castells, 1996, p. 406)

4. References Barney, D. (2004). The Network Society. Cambridge, U.K.: Polity. Benson, R., & Neveu, E. (Eds.). (2005). Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field. Cambridge, U.K.: Polity. Bourdieu, P. (1998). On Television (P. P. Ferguson, Trans.). New York: The New Press. (Note: Originally published in French, 1996.) Castells, M. (1996). The Rise of the Network Society. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, Vol. 1. Oxford: Blackwell. (Note: 2nd ed., 2000; 2nd ed. with new preface, 2010, published by John Wiley & Sons.) Castells, M. (2000a). Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society. British Journal of Sociology, 51(1), 524. DOI: 10.1080/000713100358408 Castells, M. (2000b). Toward a sociology of the network society. Contemporary Sociology, 29(5), 693 699. Castells, M. (2004a). Informationalism, networks, and the network society: A theoretical blueprint. In M. Castells (Ed.), The Network Society: A Cross-Cultural Perspective (pp. 345). Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar Publishing. Castells, M. (Ed.). (2004b). The Network Society: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar Publishing. Available: http://www.scribd.com/doc/22569675/The-Network-Society-a-Cross- cultural-perspective-Manuel-Castells-ed Castells, M. (2007). Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. International Journal of Communication, 1, 238266. Available: http://ijoc.org/ojs/index.php/ijoc/article/view/46 Compton, J. R., & Benedetti, P. (2010). Labour, new media and the institutional restructuring of journalism. Journalism Studies, 11(4), 487499. DOI:10.1080/14616701003638350 MacKinnon, R. (2011). Consent of the Networked: The Worldwide Struggle for Internet Freedom. New York: Basic Books. Madsen, M. R. (2004). Legal field or legal network? A Bourdieusian critique of Manuel Castells network society. Retfaerd, 25(4), 418. Available: http://www.retfaerd.org/old_issues/vol-25-2002 van der Haak, B., Parks, M., & Castells, M. (2012). The future of journalism: Networked journalism. International Journal of Communication, 6, 29232938. Available: http://ijoc.org/ojs/index.php/ijoc/article/view/1750/832 van Dijk, J. (2012). The Network Society, 3rd ed. London: Sage. (Note: 1st ed., 1999; 2nd ed., 2006. Originally published in Dutch, 1991.)

van Dijk, J. (1999). The one-dimensional network society of Manuel Castells. New Media and Society, 1(1), 12738. DOI: 10.1177/1461444899001001015 Volkmer, I. (2002). Journalism and political crises in the global network society. In B. Zelizer & S. Allan (Eds.), Journalism After September 11 (pp. 235246). London: Routledge. Zelizer, B., & Allan, S. (Eds.). (2002). Journalism After September 11. London: Routledge. Available: http://site.iugaza.edu.ps/mamer/files/Journalism-after-9-111.pdf

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

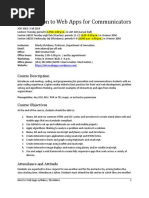

- New Media and A Democratic Society Syllabus 2018Document7 paginiNew Media and A Democratic Society Syllabus 2018Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- JOU4930 Artificial Intelligence Syllabus Spring 2021Document9 paginiJOU4930 Artificial Intelligence Syllabus Spring 2021Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Web Apps Syllabus 2019Document9 paginiWeb Apps Syllabus 2019Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advanced Web Apps Syllabus McAdams s2020Document8 paginiAdvanced Web Apps Syllabus McAdams s2020Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- JOU 4364 Advanced Web Apps s2019Document7 paginiJOU 4364 Advanced Web Apps s2019Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Web Apps Syllabus 2020Document12 paginiWeb Apps Syllabus 2020Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Advanced Social Media Syllabus 2017Document6 paginiAdvanced Social Media Syllabus 2017Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- MMC 6612 Syllabus 2017 v2Document6 paginiMMC 6612 Syllabus 2017 v2Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Intro To Web Apps Syllabus 2018Document9 paginiIntro To Web Apps Syllabus 2018Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Intro To Web Apps Syllabus 2017Document8 paginiIntro To Web Apps Syllabus 2017Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Readings MMC6612 Fall 2017Document3 paginiReadings MMC6612 Fall 2017Mindy McAdams100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Syllabus MMC4341 2015 v2Document7 paginiSyllabus MMC4341 2015 v2Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- JOU 4364 Sec 2F03 Advanced Web Apps McAdams s2018Document7 paginiJOU 4364 Sec 2F03 Advanced Web Apps McAdams s2018Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Advanced Web Apps Syllabus 2017Document7 paginiAdvanced Web Apps Syllabus 2017Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Intro To Web Apps Syllabus 2015Document7 paginiIntro To Web Apps Syllabus 2015Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Readings MMC6612 Fall 2015Document3 paginiReadings MMC6612 Fall 2015Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- MMC 6612 Syllabus 2016 v.2Document6 paginiMMC 6612 Syllabus 2016 v.2Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Media Skills Syllabus S2016Document6 paginiSocial Media Skills Syllabus S2016Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Two Code Courses For Journalism StudentsDocument3 paginiTwo Code Courses For Journalism StudentsMindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transmedia StorytellingDocument7 paginiTransmedia StorytellingMindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- MMC 6612 Syllabus 2015Document6 paginiMMC 6612 Syllabus 2015Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Readings MMC6612 Fall 2015Document3 paginiReadings MMC6612 Fall 2015Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Syllabus Social Media Management S2015Document7 paginiSyllabus Social Media Management S2015Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intro To Web Apps Syllabus 2016Document7 paginiIntro To Web Apps Syllabus 2016Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Web Apps 2 Syllabus 2016Document6 paginiWeb Apps 2 Syllabus 2016Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- MMC 6612 Syllabus 2014Document5 paginiMMC 6612 Syllabus 2014Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syllabus Social Media MGT 2014Document7 paginiSyllabus Social Media MGT 2014Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Syllabus JOU6344 Fall 2013Document7 paginiSyllabus JOU6344 Fall 2013Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Readings MMC6612 Fall 2014Document3 paginiReadings MMC6612 Fall 2014Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syllabus MMC4341 2014Document6 paginiSyllabus MMC4341 2014Mindy McAdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay Writing FCE Part 1 - Sample Task # 5 - Technological DevelopmentsDocument3 paginiEssay Writing FCE Part 1 - Sample Task # 5 - Technological DevelopmentsMaria Victoria Ferrer Quiroga100% (1)

- Why Should I Hire You - Interview QuestionsDocument12 paginiWhy Should I Hire You - Interview QuestionsMadhu Mahesh Raj100% (1)

- الترجمة اليوم PDFDocument155 paginiالترجمة اليوم PDFMohammad A YousefÎncă nu există evaluări

- ChaucerDocument22 paginiChaucerZeeshanAhmad100% (1)

- Fear and Foresight PRTDocument4 paginiFear and Foresight PRTCarrieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memento FranceDocument56 paginiMemento FranceDiana CasyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines Public SpeakingDocument4 paginiGuidelines Public SpeakingRaja Letchemy Bisbanathan MalarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Operational Planning Transforming Plans Into ActionDocument52 paginiOperational Planning Transforming Plans Into ActionDiaz Faliha100% (1)

- Linking Employee Satisfaction With ProductivityDocument6 paginiLinking Employee Satisfaction With Productivityani ni musÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment in The Primary SchoolDocument120 paginiAssessment in The Primary SchoolMizan BobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Crisis ManagementDocument9 paginiCrisis ManagementOro PlaylistÎncă nu există evaluări

- 235414672004Document72 pagini235414672004Vijay ReddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- CrucibleDocument48 paginiCrucibleShaista BielÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2022 City of El Paso Code of ConductDocument10 pagini2022 City of El Paso Code of ConductFallon FischerÎncă nu există evaluări

- EBS The Effects of The Fall of ManDocument12 paginiEBS The Effects of The Fall of ManAlbert A. MaglasangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Culture, Society and Politics - OverviewDocument56 paginiUnderstanding Culture, Society and Politics - OverviewRemy Llaneza AgbayaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organizational Development InterventionsDocument57 paginiOrganizational Development InterventionsAmr YousefÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Life Cycle of A Butterfly Lesson PlanDocument2 paginiThe Life Cycle of A Butterfly Lesson Planst950411Încă nu există evaluări

- Bayan, Karapatan Et Al Vs ErmitaDocument2 paginiBayan, Karapatan Et Al Vs ErmitaManuel Joseph FrancoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamentals of LogicDocument18 paginiFundamentals of LogicCJ EbuengaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decalogues and Principles PDFDocument31 paginiDecalogues and Principles PDFهؤلاء الذين يبحثونÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCQ On Testing of Hypothesis 1111Document7 paginiMCQ On Testing of Hypothesis 1111nns2770100% (1)

- Theoretical Framework For Conflict ResolDocument9 paginiTheoretical Framework For Conflict ResolAAMNA AHMEDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Habit 1 - Be Proactive: Stephen CoveyDocument7 paginiHabit 1 - Be Proactive: Stephen CoveyAmitrathorÎncă nu există evaluări

- George Barna and Frank Viola Interviewed On Pagan ChristianityDocument9 paginiGeorge Barna and Frank Viola Interviewed On Pagan ChristianityFrank ViolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yes, Economics Is A Science - NYTimes PDFDocument4 paginiYes, Economics Is A Science - NYTimes PDFkabuskerimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Level 3 Health and Social Care PackDocument735 paginiLevel 3 Health and Social Care PackGeorgiana Deaconu100% (4)

- Art and Aesthetics: Name Matrix NoDocument3 paginiArt and Aesthetics: Name Matrix NoIvan NgÎncă nu există evaluări

- PepsiCo Mission Statement Has Been Worded by CEO Indra Nooyi AsDocument2 paginiPepsiCo Mission Statement Has Been Worded by CEO Indra Nooyi AsSyarifah Rifka AlydrusÎncă nu există evaluări

- BONES - Yolanda, Olson - 2016 - Yolanda Olson - Anna's ArchiveDocument96 paginiBONES - Yolanda, Olson - 2016 - Yolanda Olson - Anna's ArchivekowesuhaniÎncă nu există evaluări