Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

05 CGilbertand Gubar Anxietyof Authorship

Încărcat de

Angela P.Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

05 CGilbertand Gubar Anxietyof Authorship

Încărcat de

Angela P.Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Dr.

Richard Clarke LITS2307 Notes 05C

SANDRA GILBERT AND SUSAN GUBAR THE MAD WOM AN IN THE ATTIC (1979): INFECTION IN THE SENTENCE: THE WOMAN WRITER AND THE ANXIETY OF AUTHORSHIP In this theoretical chapter of one of the seminal works of Feminist literary criticism, Gilbert and Gubar seek to define what it means to be a woman writer in a patriarchal culture where, since time imm emorial, the pen has consciously and unconsciously been conceptualised as a metaphorical penis and the author viewed in term s of a father who insem inates a text with his meaning. The central question for Feminists, according to Gilbert and Gubar, is thus: does the Queen try to sound like the King, imitating his tone, is inflections, his phrasing, his point of view? Or does she talk back to him in her own vocabulary, her own timbre, insisting on her own viewpoint? (46) To answer this, Gilbert and Gubar go back to the theories of literary history proffered by Harold Bloom , to wit, his account of the process by which writers assimilate and then consciously or unconsciously affirm or deny the achievements of their predecessors (46). They find Blooms theory of the anxiety of influence particularly useful in this respect, to be precise, the writers fear that he is not his own creator and that the works of his predecessors . . . assume essential priority over his own writings (46). Gilbert and Gubar underscore that Blooms Oedipal model of the strong poet (whereby a man can only become a poet by som ehow invalidating his poetic father [47]) is undoubtedly a masculinist one but one, as such, em inently suited to understanding the patrilinearity of Western literary history and the psychosexual and sociosexual con-texts by which every literary text is surrounded (47). They contends that Bloom s theory less recommends or perpetuates than it analyses the patriarchal poetics and attendant anxieties which underlie our cultures chief literary movem ents (48). There are two questions which accordingly present themselves to Gilbert and Gubar. Firstly, can feminist critics speak of and thus study, as Elaine Showalter does, for example, the existence of an autonomous tradition of women writers? Gilbert and Gubar seem uncomfortable with the idea that one can completely sever the ties linking womens writing with the male-dom inated canon. Moreover, even if this were desirable, they do not want to simply reverse Blooms model and to speak, thus, of a similar Oedipal process dominating relations between literary women, especially given the questions surrounding the applicability of Freuds essentially androcentric theories to women and the controversial nature of his model of femininity. Secondly, if the answer to the first question is no, where and how can / does the female writer (especially earlier ones like the Bronts) fit into the male literary tradition as described by Bloom? How can his theory of the anxiety of influence be adapted to explain the female tradition? In answer to this, Gilbert and Gubar assert that women writers experience what they term an anxiety of authorship (49) for the simple reason that she must confront precursors who are alm ost exclusively male, and therefore significantly different from her. Not only do these precursors incarnate patriarchal authority . . ., they attempt to enclose her in definitions of her person and her potential which, by reducing her to extreme stereotypes (angel, m onster) drastically conflict with her sense of self--that is, of her subjectivity, her autonomy, her creativity. (48) For the female writer, the anxiety of authorship consists, thus, in the radical fear that she cannot create, that because she can never become a precursor the act of writing will isolate or destroy her (49). Moreover, Gilbert and Gubar argue that just as the male artists struggle against his predecessor takes the form of what Bloom calls revisionary swerves, flights, misreadings, so the female writers battle for self-creation involves her in a revisionary process . . . not against her (male) predecessors reading of the world but against his reading of her. In order to define herself as an author she must redefine the term s of her socialization. Her revisionary struggle . . . often becom es a struggle for what Adrienne Rich has called Revision--the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction. . . . (49) Importantly, according to Gilbert and Gubar, the female writer often can begin such a struggle only by seeking a female precursor who, far from representing a threatening force to be denied or killed, proves by

Dr. Richard Clarke LITS2307 Notes 05C

example that a revolt against patriarchal authority is possible (49). In other words, where, for Bloom , the paternal relationship between the male writer and his predecessor is inherently conflictual and accordingly conceptualised in Oedipal terms, literary maternity is, by contrast, exemplary and peaceful, according to Gilbert and Gubar. It is in this way that the female writer seeks to legitimize her own rebellious endeavours (50). At the same time, it is a fact that one of the consequences of living in a patriarchal society is that wom en experience their gender as a painful obstacle or even a debilitating inadequacy (50). Thus, Gilbert and Gubar contend that the loneliness of the female artist, her feelings of alienation from male predecessors coupled with her need for sisterly predecessors and successors, her urgent sense of her need for a female audience together with her fear of the antagonism of m ale readers, her culturallyconditioned timidity about self-dramatization, her dread of the patriarchal authority of art, her anxiety about the impropriety of female invention all these phenomena of inferiorization mark the woman writers struggle for artistic self-definition and differentiate her efforts at self-creation from those of her male counterpart. (50) From this point of view, for both male and female writers, literary texts are coercive, imprisoning . . . literature usurps a readers interiority, it is an invasion of privacy (52).

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Budgeted Lesson. 2nd Quarter - PERDEVDocument2 paginiBudgeted Lesson. 2nd Quarter - PERDEVJonalyn BanezÎncă nu există evaluări

- NHRD Journal On Change ManagementDocument128 paginiNHRD Journal On Change Managementsandeep k krishnan100% (18)

- Passive Voice Harry Potter1Document1 paginăPassive Voice Harry Potter1Angela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Essays On Virginia WoolfDocument6 paginiEssays On Virginia WoolfAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Meditation PPT-3Document12 paginiMeditation PPT-3Rowmell Thomas0% (1)

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument2 paginiReview of Related Literature and StudiesNoldlin Dimaculangan73% (79)

- Guidelines-CLIL-materials 1A5 Rel01 PDFDocument25 paginiGuidelines-CLIL-materials 1A5 Rel01 PDFrguedezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Everyday VocabularyDocument5 paginiEveryday VocabularyAngela P.100% (1)

- New Cpe Writing TipsDocument5 paginiNew Cpe Writing TipsAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Future Tenses Future simple: will + ρήμαDocument4 paginiFuture Tenses Future simple: will + ρήμαAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Easter Egg HuntDocument1 paginăEaster Egg HuntAngela P.0% (1)

- ELSTeachers HandbookDocument89 paginiELSTeachers HandbookAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Error AnalysisDocument3 paginiError AnalysisAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Autumn PictionaryDocument1 paginăAutumn PictionaryAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Early Language Learning in EuropeDocument5 paginiEarly Language Learning in EuropeAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Farmakonisi Push Backs Public StatementsDocument2 paginiFarmakonisi Push Backs Public StatementsAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Amazing Facts Statements and AnswersDocument2 paginiAmazing Facts Statements and AnswersAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Europe Is A Fortress, Greece Is A Frontier StateDocument7 paginiEurope Is A Fortress, Greece Is A Frontier StateAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Easter Color by NumbersDocument3 paginiEaster Color by NumbersAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Events That Changes History WorksheetDocument1 paginăEvents That Changes History WorksheetAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

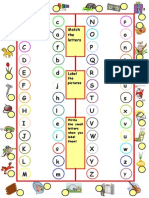

- ABC Match and LabelDocument1 paginăABC Match and LabelAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Implementing The Curriculum With CambridgeDocument59 paginiImplementing The Curriculum With Cambridgeirfan shahidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Origami Cat 2 Body InstructionsDocument1 paginăOrigami Cat 2 Body InstructionsAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Greece: The End of The Road For Refugees, Asylum-Seekers and MigrantsDocument12 paginiGreece: The End of The Road For Refugees, Asylum-Seekers and MigrantsAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Alphabets: Name: - Class: - LessonDocument1 paginăAlphabets: Name: - Class: - LessonAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- EUN+Starter+Teacher's+Book+Unit+4+9780521726382c04 p043-049Document7 paginiEUN+Starter+Teacher's+Book+Unit+4+9780521726382c04 p043-049Angela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Confusing Word Pairs: Accept / ExceptDocument8 paginiConfusing Word Pairs: Accept / ExceptAngela P.Încă nu există evaluări

- Jacob Kounin by Alang Ridhwan p5pDocument19 paginiJacob Kounin by Alang Ridhwan p5pAlang RidhwanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychology: History & PerspectivesDocument32 paginiPsychology: History & PerspectivesTreblig Dominiko MartinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motivational Theory PDFDocument36 paginiMotivational Theory PDFminchanmonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship Evaluation FormDocument3 paginiInternship Evaluation Formnaruto uzumakiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tom Coyne/Speech On LeadershipDocument3 paginiTom Coyne/Speech On LeadershipKenn BlancoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Singing Game Lesson Plan PDFDocument3 paginiSinging Game Lesson Plan PDFapi-511177039Încă nu există evaluări

- Learning at HomeDocument1 paginăLearning at Homeapi-557522770Încă nu există evaluări

- Differences in Verbal and Performance IQ in Conduct Disorder Research Findings From A Greek SampleDocument5 paginiDifferences in Verbal and Performance IQ in Conduct Disorder Research Findings From A Greek SamplePaul HartingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dilemma TrainingDocument3 paginiDilemma TrainingManuel Mejía MurgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Medical Error To Disclose or Not To Disclose 2155 9627-5-174Document3 paginiA Medical Error To Disclose or Not To Disclose 2155 9627-5-174Aduda Ruiz BenahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading Explorer 3 E 4 SB + Online WB Sticker Code KEY - UNIT 1 IMAGES OF LIFE WARM UP Possible - StudocuDocument1 paginăReading Explorer 3 E 4 SB + Online WB Sticker Code KEY - UNIT 1 IMAGES OF LIFE WARM UP Possible - StudocuBeverly AlmeidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Madeleine Leininger and The Transcultural Theory of NursingDocument8 paginiMadeleine Leininger and The Transcultural Theory of Nursingratna220693Încă nu există evaluări

- NSTP ReflectionDocument2 paginiNSTP ReflectionVheilmar ZafraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Data Collection and PresentationDocument2 paginiData Collection and PresentationKim Angel AbanteÎncă nu există evaluări

- S Rohan Rao - 1588713646 - Assignment6Document4 paginiS Rohan Rao - 1588713646 - Assignment6amitcmsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection On Field Research WorksheetDocument2 paginiReflection On Field Research Worksheetapi-369601432Încă nu există evaluări

- Motivational Theories - A Critical Analysis: June 2014Document9 paginiMotivational Theories - A Critical Analysis: June 2014jimmycia82Încă nu există evaluări

- Appraising Analogical ArgumentsDocument23 paginiAppraising Analogical Argumentskisses_dearÎncă nu există evaluări

- Establishing My Own Classroom Routines and Procedures in A Face-to-face/Remote LearningDocument10 paginiEstablishing My Own Classroom Routines and Procedures in A Face-to-face/Remote LearningBane LazoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genet HailuDocument77 paginiGenet HailuBrook LemmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Textual Notes - S-R TheoriesDocument29 paginiTextual Notes - S-R TheoriesSandesh WaghmareÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSYDocument4 paginiPSYSaqib AkramÎncă nu există evaluări

- Independent Trader: You Are An..Document7 paginiIndependent Trader: You Are An..Dimas KhairulyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treadway Lima Tire Plant - Case Analysis by Vishal JoshiDocument8 paginiTreadway Lima Tire Plant - Case Analysis by Vishal Joshivijoshi50% (2)

- 11 - Chapter 4 Basics of Research MethodologyDocument13 pagini11 - Chapter 4 Basics of Research Methodologyshivabt07Încă nu există evaluări