Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Fauna Found at Kuala Sepetang Eco Tourism

Încărcat de

lovelynjsDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Fauna Found at Kuala Sepetang Eco Tourism

Încărcat de

lovelynjsDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Fauna found at Kuala Sepetang Eco Tourism Matang Mangrove Forest is the largest and well reserved mangrove

ecosystems in Peninsular Malaysia. These ecologically abundant mangrove habitats stretch along the west coast tidal mudflats of northern Perak for almost 50km. Along the Mangrove Kuala Sepetang Estuary, there lived many types of faunas, which are such as kelipkelip, ikan belacak , dolphins, clams and eagles. This estuary was also regarded as the breeding grounds for numerous species of marine crustaceans including crabs, shrimps, lobsters, horseshoe crabs and prawns as well as fishes and shellfishes. As a fact according to the Perak State Forestry Department, in the Matang Mangrove Forest there are: 1. 28 true mangrove species and 13 associate mangrove species; 2. 19 mammals such as the Long-tailed Macaque (Macaca fascicularis), Leopard Cat (Felis bengalensis), Malayan Pangolin (Manis javanica), Smooth Otter (Lutra perspicillata), Short-tailed Mongoose (Herpestes brachyurus) and Island Flying Fox (Pteropus hypomelanus); 3. at least 155 species of birds including the Great Argus Pheasant (Argusianus argus), Buffy Fish Owl (Ketupa ketupu), Pink-necked Green Pigeon (Treron vernans), the rare Bronzed Drongo (Dicrurus aeneus) and the Mangrove Whistler (Pachycephala grisola); 4. a species of river dolphin, i.e. the Chinese White Dolphin (Sousa chinensis); 5. 112 species of modern bony fishes and 3 species of stingrays; 6. and about 50 species of crabs and 20 species of prawns and shrimps, both edible and non-edible.

During the trip along the Kuala Sepetang Eco Tourism Centre, we only managed to see certain faunas along the estuary, which are such as the kelip-kelip, ikan belacak, clams and eagles. Dolphins were supposed to be seen too but due to hot weather at that time, they did not appear on the sea surface.

1. Kelip-kelip

Bird watching and fishing are the primary activities in the morning while at night get a boat ride to see synchronized blinking lights of fireflies of Pteroptyx species on Berembang trees or Sonneratia caseolaris. Lampyridae is a family of insects in the beetle order Coleoptera. They are winged beetles, and commonly called fireflies or lightning bugs for their conspicuous crepuscular use of bioluminescence to attract mates or prey. Fireflies produce a "cold light", with no infrared or ultraviolet frequencies. This chemically produced light from the lower abdomen may be yellow, green, or pale-red, with wavelengths from 510 to 670 nanometers. About 2,000 species of firefly are found in temperate and tropical environments. Many are in marshes or in wet, wooded areas where their larvae have abundant sources of food. These larvae emit light and are often called "glowworms", in particular, in Eurasia. In many species, both male and female fireflies have the ability to fly, but in some species, females are flightless.

Figure 1(b): Firefly (species unknown) captured in eastern Canada ; the top picture is taken with a flash, the bottom only with the self-emitted light.

Fireflies tend to be brown and soft-bodied, often with the elytra (front wings) more leathery than in other beetles. Although the females of some species are similar in appearance to males, larviform females are found in many other firefly species. These females can often be distinguished from the larvae only because they have compound eyes. The most commonly known fireflies are nocturnal, although there are numerous species that are diurnal. Most diurnal species are nonluminescent, however, some species that remain in shadowy areas may produce light. A few days after mating, a female lays her fertilized eggs on or just below the surface of the ground. The eggs hatch three to four weeks later, and the larvae feed until the end of the summer. The larvae are commonly called glowworms. The term glowworm is also used for both adults and larvae of species such as Lampyris noctiluca, the common European glowworm, in which only the nonflying adult females glow brightly and the flying males glow only weakly and intermittently. Fireflies hibernate over winter during the larval stage, some species for several years. Some do this by burrowing underground, while others find places on or under the bark of trees. They emerge in the spring. After several weeks of feeding, they pupate for 1.0 to 2.5 weeks and emerge as adults. The larvae of most species are specialized predators and feed on other larvae, terrestrial snails, and slugs. One such species is Alecton discoidalis, which is found in Cuba. Some are so specialized, they have grooved mandibles that deliver digestive fluids directly to their prey. Adult diet varies. Some are predatory, while others feed on plant pollen or nectar. Most fireflies are quite distasteful to and sometimes poisonous to vertebrate predators. This is due at least in part to a group of steroid pyrones known as lucibufagins (LBGs), which are similar to cardiotonic bufadienolides found in some poisonous toads.

Light production in fireflies is due to a type of chemical reaction called bioluminescence. This process occurs in specialised light-emitting organs, usually on a firefly's lower abdomen. The enzyme luciferase acts on theluciferin, in the presence of magnesium ions, ATP, and oxygen to produce light. Genes coding for these substances have been inserted into many different organisms. All fireflies glow as larvae. Bioluminescence serves a different function in lampyrid larvae than it does in adults. It appears to be a warning signal to predators, since many firefly larvae contain chemicals that are distasteful or toxic. Light in adult beetles was originally thought to be used for similar warning purposes, but now its primary purpose is thought to be used in mate selection. Fireflies are a classic example of an organism that uses bioluminescence for sexual selection. They have a variety of ways to communicate with mates in courtships: steady glows, flashing, and the use of chemical signals unrelated to photic systems. Some species, especially lightning bugs of the genera Photinus, Photuris, and Pyractomena, are distinguished by the unique courtship flash patterns emitted by flying males in search of females. In general, females of the Photinus genus do not fly, but do give a flash response to males of their own species. Tropical fireflies, in particular, in Southeast Asia, routinely synchronise their flashes among large groups. This phenomenon is explained as phase synchronization and spontaneous order. At night along river banks in the Malaysian jungles (the most notable ones found near Kuala Selangor), fireflies ( kelip-kelip in the Malay language or Bahasa Malaysia) synchronise their light emissions precisely. Current hypotheses about the causes of this behavior involve diet, social interaction, and altitude. Female Photuris fireflies are known for mimicking the mating flashes of other "lightning bugs" for the sole purpose of predation. Target males are attracted to what appears to be a suitable mate, and are then eaten. For this reason the Photuris species are sometimes referred to as "femme fatalefireflies." Many fireflies do not produce light. Usually these species are diurnal, or day-flying, such as those in the genus Ellychnia. A few diurnal fireflies that inhabit primarily shadowy places, such as beneath tall plants or trees, are luminescent. One such genus is Lucidota. These fireflies use pheromones to signal mates. This is supported by the fact that some basal groups do not show bioluminescence and, rather, use chemical signaling. Phosphaenus hemipterus has photic organs, yet is a diurnal firefly and displays large antennae and small eyes. These traits strongly suggests pheromones are used for sexual selection, while photic organs are used for warning signals. In controlled experiments, males coming from downwind arrived at females first, thus male arrival was correlated with wind direction, indicating males' chemotaxis into a pheromone plume. Males were also found to be able to find females without the use of visual cues, when the sides of test Petri dishes were covered with black tape. This and the facts that females do not light up at night and males are diurnal point to the conclusion that sexual communication in P. hemipterus is entirely based on pheromones. 2. Ikan belacak (Mudskipper) (Genus Periophthalmus)

Figure 2(a): Periophthalmus gracilis (from Malaysia to North Australia) Mudskippers are members of the subfamily Oxudercinae (tribe Periophthalmini),[1] within the family Gobiidae (Gobies). They are completely amphibious fish, fish that can use their pectoral fins to walk on land.[2][3] Being amphibious, they are uniquely adapted to intertidal habitats, unlike most fish in such habitats which survive the retreat of the tide by hiding under wet seaweed or in tidal pools.[4] Mudskippers are quite active when out of water, feeding and interacting with one another, for example to defend their territories. They are found in tropical, subtropical and temperate regions, including the Indo-Pacific and the Atlantic coast of Africa. Compared with fully aquatic gobies, these fish present a range of peculiar behavioural and physiological adaptations to an amphibious lifestyle. These include:

Anatomical and behavioural adaptations that allow them to move effectively on land as well as in the water.[3] As their name implies, these fish use their fins to move around in a series of skips. They can also flip their muscular body to catapult themselves up to 2 feet (60 cm) into the air.[5] The ability to breathe through their skin and the lining of their mouth (the mucosa) and throat (the pharynx). This is only possible when the mudskipper is wet, limiting mudskippers to humid habitats and requiring that they keep themselves moist. This mode of breathing, similar to that employed by amphibians, is known as cutaneous air breathing.[4] Another important adaptation that aids breathing while out of water are their enlarged gill chambers, where they retain a bubble of air. These large gill chambers close tightly when the fish is above water, keeping the gills moist, and allowing them to function. They act like a scuba diver's cylinders, and supply oxygen for respiration also while on land.[4] Digging deep burrows in soft sediments allow the fish to thermoregulate,[6] avoid marine predators during the high tide when the fish and burrow are submerged,[7] and for laying their eggs.[8]

Even when their burrow is submerged, mudskippers maintain an air pocket inside it, which allows them to breathe in conditions of very low oxygen concentration.[9][10][11] The genus Periophthalmus is by far the most diverse and widespread genus of mudskipper. Eighteen species have been described.[12][13][14] Periophthalmus argentilineatus is one of the most widespread and well known species. It can be found in mangrove ecosystems and mudflats of East Africa and Madagascar east through the Sundarbans of Bengal, Southeast Asia to Northern Australia, southeast China and southern Japan, up to Samoa and Tonga Islands.[1] It grows to a length of about 9.5 cm [1] and is a carnivorous opportunist feeder. It feeds on small prey such as small crabs and

other arthropods.[15] Another species, Periophthalmus barbarus, is the only oxudercine goby that inhabits the coastal areas of western Africa.[1]

3. Dolphins

Figure 3(a): Dolphin showing itself to the public.

Figure 3(b): Dolphin

Occasionally, the Chinese White Dolphin (Sousa chinensis), also known as the Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin, can be spotted swimming along the river-mouths. This dolphin is one of the 2 known species of pink freshwater dolphins found in the world. A native of Southeast Asia, the dolphin is either white or pink-skinned and can grow to the length of 3.5 metres. There is also a prehistoric archaeological site in Pulau Kelumpang. Out to the sea, visitors on boats may also be fortunate enough to see dugongs (Dugong dugon) swimming near the river deltas.

4. Kerang

Figure 4(a): Kerang being cleaned.

Figure 4(b): A final clean before the Kerang are ready to go out.

5. Eagle (Burung Helang)

Figure 5(a): Eagles flying gracefully in the air

Along the coastline and near to villages, tourists will be welcomed by the sight of Brahminy Kites (Haliastur indus). This stunning Malaysian mystery bird is actually the official mascot of Jakarta. This is an adult Brahminy kite, Haliastur indus, a medium-sized accipiter. This species can be distinguished from other closely-related kites by its rounded tail (both the black kite, Milvus migrans, and red kite, M. milvus, have V-shaped tails), rich chestnut plumage and contrasting white head and breast, and large, dark eyes. These birds are fairly common throughout Southeast Asia, India and Australia, and generally make their living by either scavenging seafood or kleptoparasitism (stealing prey from other birds), but they will sometimes hunt bats or hares.

6. Milky Stork

Figure 6(a): Milky Stork resting above the trees.

Kuala Gula Bird Sanctuary is within the Matang Mangrove Forest Reserve, which is located along the coast of Perak, 43 km or less than an hour's drive from Taiping town. Kuala Gula is renowned for its diversity of wildlife especially amongst birdwatchers for it is a hotspot for waterbirds, both resident and migratory species. Various waterbird/migratory species can be observed from the end of August until April the following year. Nearly two hundreds bird species including migratory species, have been recorded. Estimated more than 200,000 migratory birds to stop over here every year. Endangered species such as the Milky Stork Mycteria cinerea, Lesser Adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus), Chinese Egret (Egretta eulophotes) and Common Greenshank (Tringa nebularia) can be found along the Kuala Sepetang Estuary. The Milky Stork (Mycteria cinerea) is a large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. This mediumsized stork can reach a height of 91 to 95 cm (36 to 37 in), with a wing chord length of 43.550 cm (17.1 20 in), a culmen length of 19.427.5 cm (7.610.8 in), a tarsus length of 18.825.5 cm (7.410.0 in) and a tail of 14.517 cm (5.76.7 in).[2] The sexes look similar. The plumage is general white contrasted with a naked red face and a long shiny green-black tail and flight-feathers. This species occurs in Cambodia, Peninsular Malaysia and the Indonesian islands of Sumatra, Java, Bali, Sumbawa, Sulawesi and Buton. The milky stork feeds on fish, amphibians and small rodents. It is classified as vulnerable owing to loss of coastal habitat, hunting and trade.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Codex of The BeastlandsDocument20 paginiCodex of The Beastlandselements cityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Origami Artist's Bible (PDFDrive)Document599 paginiOrigami Artist's Bible (PDFDrive)Natzu CalixtoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Worksheet - Non-Mendelian TraitsDocument4 paginiWorksheet - Non-Mendelian TraitsJude GÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Terminologies in Animal Science and Other Related InformationDocument6 paginiTerminologies in Animal Science and Other Related InformationOliver Talip100% (4)

- Exalted 3E - Hundred Devils Night Parade (COMPILED)Document93 paginiExalted 3E - Hundred Devils Night Parade (COMPILED)241again100% (7)

- Poultry Housing EquipmentDocument24 paginiPoultry Housing Equipmentgemma salomonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 Principles of An EagleDocument3 pagini7 Principles of An EagleBatool Khan100% (5)

- Owls in The Family Full Story.Document2 paginiOwls in The Family Full Story.kasthuri100% (1)

- Agriculture Science SbaDocument11 paginiAgriculture Science Sbataylor noelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise Bahasa InggrisDocument4 paginiExercise Bahasa Inggrisenglish teacherÎncă nu există evaluări

- VERB TYPES AND FORMSDocument5 paginiVERB TYPES AND FORMSAadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1st Maths Term I EM - WWW - Tntextbooks.inDocument66 pagini1st Maths Term I EM - WWW - Tntextbooks.inSara SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Finches and their nesting habitsDocument2 paginiFinches and their nesting habitsNitish SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- IEO (International English Olympiad) Class 4 Past Paper (Previous Year) Paper 2014 Part 2 Download All The Papers For 2020 ExamDocument2 paginiIEO (International English Olympiad) Class 4 Past Paper (Previous Year) Paper 2014 Part 2 Download All The Papers For 2020 ExamVenkatajagadeesh p100% (1)

- Dialogues Vowels Ord1 SPDocument11 paginiDialogues Vowels Ord1 SPJustina ReyÎncă nu există evaluări

- METAMORPHOSISDocument27 paginiMETAMORPHOSISPhoebe O. TumammanÎncă nu există evaluări

- ENGLISHDocument12 paginiENGLISHPingcy UriarteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bird, A Single Species That Constitutes The Family Balaenicipitidae (Order BalaenicipitiformesDocument2 paginiBird, A Single Species That Constitutes The Family Balaenicipitidae (Order BalaenicipitiformesSANCHEZ PRINCESS MAEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Know The Bear Facts For Kids: Black Bears in New Jers Ey Activity GuideDocument16 paginiKnow The Bear Facts For Kids: Black Bears in New Jers Ey Activity GuidenervozaurÎncă nu există evaluări

- 50 Remarkable Facts About ButterfliesDocument59 pagini50 Remarkable Facts About Butterfliesdesign designÎncă nu există evaluări

- Song I've Got A RabbitDocument2 paginiSong I've Got A RabbitLady RakkelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Animal Mystery IIDocument1 paginăAnimal Mystery IInikitetÎncă nu există evaluări

- EnglishDocument11 paginiEnglishdmarandiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Adventures of Danny Meadow MouseDocument33 paginiThe Adventures of Danny Meadow MousesaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- How People Can Help Endangered BluebirdsDocument8 paginiHow People Can Help Endangered BluebirdsLinh LuuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stages in The Life Cycle of OrganismsDocument44 paginiStages in The Life Cycle of OrganismsCatherine Renante100% (1)

- Endangered Animals LessonDocument2 paginiEndangered Animals LessonMasoumeh RassouliÎncă nu există evaluări

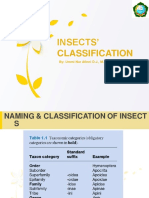

- Klasifikasi SeranggaDocument129 paginiKlasifikasi SeranggaUmmi Nur AfinniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sinhalese Folklore NotesDocument79 paginiSinhalese Folklore NotesDummy MailÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test 3Document4 paginiTest 3Ilmi UsfadilaÎncă nu există evaluări