Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Kevin MacDonald - Immigration and The Unmentionable Question of Ethnic Interests

Încărcat de

whitemaleandproud0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

249 vizualizări5 paginiPeter bergen: arguments over immigration are usually limited to cultural or economic factors. He says No one wants to talk about the 800-lb. Gorilla sitting over there in the corner. Immigration enthusiasts are quick to smear environmental concerns as "the greening of hate," bergen says.

Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Kevin MacDonald - Immigration and the Unmentionable Question of Ethnic Interests

Drepturi de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

RTF, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentPeter bergen: arguments over immigration are usually limited to cultural or economic factors. He says No one wants to talk about the 800-lb. Gorilla sitting over there in the corner. Immigration enthusiasts are quick to smear environmental concerns as "the greening of hate," bergen says.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca RTF, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

249 vizualizări5 paginiKevin MacDonald - Immigration and The Unmentionable Question of Ethnic Interests

Încărcat de

whitemaleandproudPeter bergen: arguments over immigration are usually limited to cultural or economic factors. He says No one wants to talk about the 800-lb. Gorilla sitting over there in the corner. Immigration enthusiasts are quick to smear environmental concerns as "the greening of hate," bergen says.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca RTF, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 5

VDARE.COM - http://www.vdare.com/macdonald/041027_immigration.

htm

October 27, 2004

Immigration And The Unmentionable

Question Of Ethnic Interests

By Kevin MacDonald

[Previously by Kevin MacDonald: Was the 1924 Immigration Cut-off "Racist"? and

Thinking About Neoconservatism]

Arguments over immigration are usually limited to cultural or economic factors. Political

scientists like Samuel Huntington point out that the culture of the countHYPERLINK

"http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=2495&print=1%5d"ry will

change dramatically if there is a continued influx of Spanish-speaking immigrants. And

economists like George Borjas have demonstrated that large masses of newcomers

depress wages and create enormous demands on the environment and on public services,

especially health care and education.

These lines of argument are, of course, legitimate. But there always seems to be an

element of timidity present. No one wants to talk about the 800-lb. gorilla sitting over

there in the corner—the issue of ethnic interests.

Any attempt to bring up the ethnic issue is usually strangled in the cradle. Indeed, other

lines of argument are frequently met by assertions that they are masking ethnic concerns.

Thus immigration enthusiasts are quick to smear arguments that immigration will harm

the environment as "the greening of hate."

This strategy has been highly effective—because, if there is one area where the

intellectual left has won a complete and decisive victory, it is in pathologizing any

consideration by the European majority of the United States of its own ethnic interests.

By "pathologizing" I mean not only that people have been indoctrinated that their

commonsense perceptions of race and ethnicity are an "illusion," but, further, that the

slightest assertion of ethnic self-interest or consciousness by the European majority of the

United States is the sign of a grave moral defect—so grave that it is a matter of

psychiatric concern.

Of course, this is hypocritical. While assertions of ethnic interest by Europeans are

stigmatized, assertions of ethnic interest by other groups are utterly commonplace.

Mexican activists loudly advertise their goal of reconquering the Southwestern United

States via immigration from Mexico—which would obviously be in the ethnic interests of

Mexicans but would presumably harm the interests of European-Americans. Jewish

organizations, in the forefront of the intellectual and political battle to pathologize the

ethnic interests of European Americans, have simultaneously been deeply involved in

organizing coalitions of minority ethnic groups to assert their political interests in

Congress and in the workplace. Plus the Jewish effort on behalf of their ethnic brethren in

Israel is legendary—and can only be described as awesomely effective.

I believe we should get rid of the hypocrisy and discuss ethnic interests openly and

honestly.

Until recently, ethnic interests were understood intuitively by everyone. People have an

interest, or "stake" in their ethnic group in exactly the same way that parents have a

genetic interest in raising their children. By bringing up my children, I ensure that my

unique genes are passed on to the next generation. This is the fundamental principle of

Darwin’s theory of evolution. But in defending my ethnic interests, I am doing the same

thing—ensuring that the genetic uniqueness of my ethnic group is passed into the next

generation.

And this is the case even if I don’t have children myself: I succeed genetically when my

ethnic group as a whole prospers.

A major step forward in the scientific analysis of ethnicity is Frank Salter’s book On

Genetic Interests: Family, Ethny, and Humanity in an Age of Mass Migration. Salter’s

basic purpose is to quantify how much genetic overlap people in the same ethnic group or

race share, as compared to people from different ethnic groups or races.

Different human ethnic groups and races have been separated for thousands of years.

During this period, they have evolved some genetic distinctiveness.

But, Salter notes, measuring these differences is now a straightforward process, thanks to

the work of researchers like Luigi Cavalli-Sforza whose book The History and

Geography of Human Genes documents the genetic distances between human groups.

It turns out that the distances between human populations correspond approximately to

what a reasonably well-informed historian or demographer or tourist would expect. For

instance, Scandinavians have greater overlap of genetic interests with other

Scandinavians than other Europeans. Europeans have a greater genetic interest in other

Europeans than in Africans.

In fact, on average, people are as closely related to other members of their ethnic group,

versus the rest of the world, as they are closely related to their grandchildren, versus the

rest of their ethnic group.

Salter suggests we think of it this way: citing authors like Garret Hardin and E. O.

Wilson, he argues that we can’t just keep on expanding our numbers and usage of

resources indefinitely. If immigrants contribute to the economy in ways that the native

population cannot, the national carrying capacity is raised. But if they are a drain on

resources or even of average productivity, they must take the place of potential native-

born in the ultimate total population. It’s a zero-sum game.

Let’s suppose that immigrants have equal capacities to the native born. Then if 10,000

Danes emigrate to England and ultimately substitute for 10,000 English natives, the

average Englishman loses the genetic equivalent of 167 children (or siblings) in the

ultimate total population, because of the close genetic relationship between Denmark and

England This is not a great loss.

However, if 10,000 Bantu emigrate to England and substitute for 10,000 English natives,

the average Englishman loses the genetic equivalent of 10,854 children (or siblings).

And, of course, it works the opposite way as well: If 10,000 English emigrate to a Bantu

territory and substitute for 10,000 Bantu natives, the average Bantu loses the equivalent

of 10,854 children (or siblings).

This is a staggering loss. Small wonder that people tend to resist the immigration of

others into their territory. At stake is an enormous family of close relatives. And history

is replete with examples of displacement migration—for example, Europeans displacing

Native Americans, Jews displacing Palestinians in Israel, Albanians displacing Serbs

from Kosovo.

All of the losers in these struggles would have been better off genetically and every other

way, if they had prevented the immigration of the group that eventually came to dominate

the area.

Nevertheless, the big story of immigration since World War II is that wealthy Western

societies, with economic opportunities and a high level of public goods such as medical

care and education, have become magnets for immigration from around the world.

Because of this immigration, and high fertility among many immigrant ethnic groups, the

result is rapid displacement of the founding populations, not only in the United States, but

also in Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, and The Netherlands, Germany and Italy.

If present trends continue, the United States’ founding European-derived population is set

to become a minority by the middle of this century. In the British Isles, the submergence

date is just two generations later, around 2100.

European populations that are allowing themselves to be displaced are playing a very

dangerous game—dangerous because of the long history of ethnic strife furnishes them

no guarantees about the future. Throughout history there has been a propensity for

majority ethnic groups to oppress minorities. A glance at Jewish history is sufficient to

make clear the dangers faced by an ethnic group that does not have a state and political

apparatus to protect its interests.

It does not take an overactive imagination to see that how coalitions of minority groups

could compromise the interests of formerly dominant European groups. We already see

numerous examples where coalitions of minority groups attempt to influence public

policy against the interests of the European majority—for example, "affirmative action"

hiring quotas and immigration policy.

Besides coalitions of ethnic minorities, the main danger facing Europeans is that wealthy,

powerful European elites are often unaware of, or do not value, their own ethnic interests.

Frequently, they in effect sell out their own ethnic groups for short-run personal gain.

There are many contemporary examples, most notably the efforts by major corporations

to import low wage workers and outsource jobs to foreign countries.

Of course, these elite Westerners are the last to suffer personally from ethnic

replacement. They are able to live in gated communities and send their children to private

schools. They are intensely interested in obtaining wealth and power in order to promote

the interests of their immediate family, or, sometimes, their social class. But they

completely ignore their enormous family of ethnic kin.

This extreme individualism of Western elites is a tragic mistake for all ethnic Europeans

—including the elites themselves, who are losing untold millions of ethnic kin by

promoting mass immigration of non-Europeans. It is a case of putting short-run class

interest and self-interest before long-run ethnic interest.

In the long run, globalism and multiculturalism are a threat to almost everyone’s ethnic

interest because both ideologies actually legitimize and increase ethnic competition.

Globalism results in increased competition because everyone has potential access to

everyone else’s territory, opening opportunities for plundering another's backyard.

Multicultural societies sanction ethnic mobilization because they inevitably become

cauldrons of competing ethnic interests.

In this very dangerous game of ethnic competition, some ethnic groups are better

prepared than others. Ethnic groups differ in intelligence and ability to control economic

resources. They differ in their degree of ethnocentrism, in the extent to which they are

mobilized to achieve group interests, and in how aggressively they behave toward other

groups. They differ in their numbers, fertility, and the extent to which they encourage

responsible parenting. They differ in the amount of land and other resources held at any

point in time and in their political power.

Given these differences, it is difficult at best to ensure peaceful relations among ethnic

groups. Even maintaining a status quo in territory and resource control is very arduous, as

can be seen by the ill-fated attempts of Americans to achieve an ethnic status quo with

the 1924 immigration law. Accepting a status quo would not be in the interests of groups

that have recently lost land or numbers. It would also likely be unacceptable both to

groups with relatively low numbers and control of resources and, conversely, to high-

fertility groups.

Yet the alternative—that all humans renounce their ethnic group loyalties—seems

unrealistic and utopian.

Indeed, given that some ethnic groups, especially ones with high levels of ethnocentrism

and mobilization, will undoubtedly continue to function as groups far into the foreseeable

future, unilateral renunciation of ethnic loyalties by other groups means only their

surrender and defeat and disappearance—the Darwinian dead end of extinction.

The future, then, like the past, will inevitably be a Darwinian competition. And ethnicity

will play a crucial role.

Salter’s conclusion: the best way to preserve ethnic interests is to defend an ethnostate—a

political unit that is explicitly intended to preserve the ethnic interests of its citizens.

Promoting ethnostates is not only fair, it also serves the interests of most peoples. All

existing nations are vulnerable to displacement by highly mobilized ethnic minorities,

especially if the minorities have high fertility.

As Frank Salter argues, a far better solution is to acknowledge everyone’s right to live in

a state dominated by their ethnic group.

This "universal nationalism" would allow people the right to live in an ethnostate that

would protect their ethnic interests—and therefore, by extension, the genetic interests of

the vast majority of the human race.

Kevin MacDonald [email him] is Professor of Psychology at California State University-

Long Beach.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Touch Grass: Antelope Hill Writing Competition 2023De la EverandTouch Grass: Antelope Hill Writing Competition 2023Încă nu există evaluări

- Kevin MacDonald - Can The Jewish Model Help The West To SurviveDocument8 paginiKevin MacDonald - Can The Jewish Model Help The West To Survivewhitemaleandproud100% (1)

- Kevin MacDonald - Understanding Jewish InfluenceDocument28 paginiKevin MacDonald - Understanding Jewish Influencewhitemaleandproud67% (3)

- The Story of the Bank of England (A History of English Banking, and a Sketch of the Money Market)De la EverandThe Story of the Bank of England (A History of English Banking, and a Sketch of the Money Market)Încă nu există evaluări

- Chaim Weizmann's Letter To MR Churchill, September 10, 1941: Quick NavigationDocument3 paginiChaim Weizmann's Letter To MR Churchill, September 10, 1941: Quick Navigationgiorgio802000Încă nu există evaluări

- Understanding NSDocument17 paginiUnderstanding NSKazo NicolajÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Conquest of a Continent; or, The Expansion of Races in AmericaDe la EverandThe Conquest of a Continent; or, The Expansion of Races in AmericaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kevin MacDonald - Was The 1924 Inmmigration Cut-Off RacistDocument8 paginiKevin MacDonald - Was The 1924 Inmmigration Cut-Off RacistwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Nation in the Village: The Genesis of Peasant National Identity in Austrian Poland, 1848–1914De la EverandThe Nation in the Village: The Genesis of Peasant National Identity in Austrian Poland, 1848–1914Evaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Anti-Imperialism CritiquedDocument21 paginiAnti-Imperialism CritiquedSmith JohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Essay On The Inequality of The Human Races - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument4 paginiAn Essay On The Inequality of The Human Races - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopedialimechipÎncă nu există evaluări

- Professor Kevin MacDonald - Critique of JudaismDocument29 paginiProfessor Kevin MacDonald - Critique of JudaismShane Webster33% (3)

- Black Invention MythsDocument16 paginiBlack Invention MythsjoetylorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kenneth Molyneaux - Klassen (Fiction)Document122 paginiKenneth Molyneaux - Klassen (Fiction)theoriginsofmidgardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joseph Goebbels - Communism With The Mask OffDocument32 paginiJoseph Goebbels - Communism With The Mask OffSkylock122100% (1)

- TBR 2015 CatalogDocument24 paginiTBR 2015 CatalogHennot Do Norte0% (1)

- Kevin McDonald - Stalin's Willing Executioners - VdareDocument8 paginiKevin McDonald - Stalin's Willing Executioners - Vdarewhitemaleandproud100% (3)

- Black Innovation V S HerrellDocument4 paginiBlack Innovation V S HerrellAbegael880% (1)

- 02 TcoaDocument455 pagini02 TcoaNikos Athanasiou100% (2)

- The Good Society - Matt KoehlDocument8 paginiThe Good Society - Matt Koehlulfheidner9103100% (1)

- 1935 - New Light On The ProtocolsDocument19 pagini1935 - New Light On The Protocolsmamacita puercoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Irrefutable Evidence Against The HolocaustDocument5 paginiIrrefutable Evidence Against The HolocaustRené D. MonkeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allied Plans For Annihilation of The German People 19pgDocument19 paginiAllied Plans For Annihilation of The German People 19pgPeterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tribal Marxism For Dummies - Gilad AtzmonDocument11 paginiTribal Marxism For Dummies - Gilad AtzmonVictoriaGiladÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jewish World PlagueDocument4 paginiJewish World PlagueMario ChalupÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hans F. K. GüntherDocument4 paginiHans F. K. GüntherMaryAnnSimpsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- George Soros Your Enemy by Daniel EstulinDocument16 paginiGeorge Soros Your Enemy by Daniel EstulinZebdequitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lob78 Lost ImperiumDocument10 paginiLob78 Lost Imperiumshaahin13631363Încă nu există evaluări

- The Revisionist - Journal For Critical Historical Inquiry - Volume 2 - Number 2 (En, 2004, 122 S., Text)Document122 paginiThe Revisionist - Journal For Critical Historical Inquiry - Volume 2 - Number 2 (En, 2004, 122 S., Text)hjuinix100% (1)

- Rudolf Report 01f4ad01Document455 paginiRudolf Report 01f4ad01polish_327923Încă nu există evaluări

- Pierce GeorgeLincolnRockwell ANationalSocialistLifeDocument38 paginiPierce GeorgeLincolnRockwell ANationalSocialistLifeulfheidner9103Încă nu există evaluări

- George Lincoln RockwellDocument32 paginiGeorge Lincoln RockwellrayaroburÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Jewish Question - A Marxist Interpretation (1946) - Abram LeonDocument96 paginiThe Jewish Question - A Marxist Interpretation (1946) - Abram LeonFabi KrongoldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kevin MacDonald - Jewish Involvement in Shaping American Immigration Policy 1881-1965Document56 paginiKevin MacDonald - Jewish Involvement in Shaping American Immigration Policy 1881-1965whitemaleandproud100% (1)

- Cold War Axis-Soviet Anti-Zionism & The American Right (Kerry Bolton, 2009)Document11 paginiCold War Axis-Soviet Anti-Zionism & The American Right (Kerry Bolton, 2009)ayazan2006Încă nu există evaluări

- Pyreaus Library Article Fire Blood Tears April19Document42 paginiPyreaus Library Article Fire Blood Tears April19rkomar333Încă nu există evaluări

- Designs of The Jews On Art and Architecture (c.1950s) - Father FeeneyDocument5 paginiDesigns of The Jews On Art and Architecture (c.1950s) - Father Feeneysaskomanev25470% (1)

- Mein Side of The Story: Key World War II Addresses of Adolf HitlerDocument145 paginiMein Side of The Story: Key World War II Addresses of Adolf Hitlernonono619Încă nu există evaluări

- Revilo Pendleton OliverDocument1 paginăRevilo Pendleton OliverCorneliu MeciuÎncă nu există evaluări

- JewishWarOfSurvival - Arnold LeeseDocument69 paginiJewishWarOfSurvival - Arnold Leeseperegrine200200Încă nu există evaluări

- HY E Rite: Evin AC OnaldDocument6 paginiHY E Rite: Evin AC OnaldErlin ErlinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bolton - Thinkers of The RightDocument98 paginiBolton - Thinkers of The RightGuy Deverell100% (3)

- The Crucifixion of PalestineDocument5 paginiThe Crucifixion of PalestineSaleh VallanderÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Racist Roots of Gun ControlDocument10 paginiThe Racist Roots of Gun ControlAmmoLand Shooting Sports NewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Why Do They Hate Us So?" A Western Scholar's Reply: Puppet MastersDocument6 pagini"Why Do They Hate Us So?" A Western Scholar's Reply: Puppet Mastersfrank_2943Încă nu există evaluări

- Vassula Ryden-Constance CumbeyDocument3 paginiVassula Ryden-Constance CumbeyFrancis LoboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Karl Marx - On The Jewish QuestionDocument23 paginiKarl Marx - On The Jewish QuestionNeena ThurmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alfred Rosenberg The Track of The Jew Through The AgesDocument215 paginiAlfred Rosenberg The Track of The Jew Through The Agesstrikes holo100% (1)

- Maurice Samuel - You GentilesDocument110 paginiMaurice Samuel - You GentilesMichael100% (2)

- The Left, the Right, and Social Revolt – Part 2Document14 paginiThe Left, the Right, and Social Revolt – Part 2Zinga187Încă nu există evaluări

- Six Million Open GatesDocument271 paginiSix Million Open Gatesimorthal100% (2)

- Was The Holocaust Reported by The Allies Exaggerated?Document2 paginiWas The Holocaust Reported by The Allies Exaggerated?Xinyu Hu100% (1)

- Book History Patton U of U - History - The Murder of General PattonDocument5 paginiBook History Patton U of U - History - The Murder of General PattonKevin CareyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carlos Whitlock-Porter - Made in Russia The HolocaustDocument428 paginiCarlos Whitlock-Porter - Made in Russia The Holocaustfredodeep76Încă nu există evaluări

- An Interview With Michael A. Hoffman IIDocument18 paginiAn Interview With Michael A. Hoffman IIEdward de Burseblades100% (2)

- Norwegian Fascism in A Transnational PerDocument25 paginiNorwegian Fascism in A Transnational PerSmith JohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Report To Himmler On EvolaDocument3 paginiA Report To Himmler On EvolahyperboreanpublishingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Creek - The Corn Fable - Vce NakonvkuceDocument5 paginiCreek - The Corn Fable - Vce NakonvkucewhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kazakh Verbal Structures and Descriptive Verbs - Sample PagesDocument6 paginiKazakh Verbal Structures and Descriptive Verbs - Sample PageswhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Certain Aspects of The Dutch Influence On PapiamentuDocument270 paginiCertain Aspects of The Dutch Influence On Papiamentuwhitemaleandproud100% (1)

- YDLI The Carrier SyllabicsDocument7 paginiYDLI The Carrier SyllabicswhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zaar TextsDocument89 paginiZaar TextswhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- English-Thai Avian Flu GlossaryDocument34 paginiEnglish-Thai Avian Flu GlossarywhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cherokee Clitics - The Word Boundary ProblemDocument14 paginiCherokee Clitics - The Word Boundary ProblemwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muskokee or Creek First Reader - Robertson and WinslettDocument25 paginiMuskokee or Creek First Reader - Robertson and WinslettwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tuscarora - Early Vocabularies and Dictionary Development - A Cautionary Note ERICDocument10 paginiTuscarora - Early Vocabularies and Dictionary Development - A Cautionary Note ERICwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- English-Burmese Avian Flu GlossaryDocument30 paginiEnglish-Burmese Avian Flu GlossarywhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Choctaw Sketch - BroadwellDocument76 paginiChoctaw Sketch - BroadwellwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zaar GrammarDocument35 paginiZaar GrammarwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hupa Language Dictionary 2nd Ed 1996Document131 paginiHupa Language Dictionary 2nd Ed 1996whitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Amdo Dialect of LabrangDocument31 paginiThe Amdo Dialect of LabrangwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching English To The Lao - Revised VersionDocument57 paginiTeaching English To The Lao - Revised VersionwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Citizens of A Non-Existent State - LatviaDocument32 paginiCitizens of A Non-Existent State - LatviawhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zaar English Hausa DictionaryDocument111 paginiZaar English Hausa DictionarywhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kazakh Textbook Beginning and Intermediate - Sample PagesDocument15 paginiKazakh Textbook Beginning and Intermediate - Sample PageswhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pagini6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- The Reality of Red Subversion The Recent Confirmation of Soviet Espionage in AmericaDocument15 paginiThe Reality of Red Subversion The Recent Confirmation of Soviet Espionage in Americawhitemaleandproud100% (3)

- Zaar Appendice III GreetingsDocument4 paginiZaar Appendice III GreetingswhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zaar Dictionary Grammar Texts - IntroDocument9 paginiZaar Dictionary Grammar Texts - IntrowhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zaar - English-Zaar IndexDocument33 paginiZaar - English-Zaar IndexwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kevin McDonald - Stalin's Willing Executioners - VdareDocument8 paginiKevin McDonald - Stalin's Willing Executioners - Vdarewhitemaleandproud100% (3)

- Kevin MacDonald - Understanding Jewish Influence III - Neoconservatism As A Jewish MovementDocument61 paginiKevin MacDonald - Understanding Jewish Influence III - Neoconservatism As A Jewish Movementwhitemaleandproud100% (1)

- Kevin MacDonald - Understanding 1 Background Traits For Jewish ActivismDocument36 paginiKevin MacDonald - Understanding 1 Background Traits For Jewish ActivismwhitemaleandproudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kevin MacDonald - Thinking About NeoconservatismDocument6 paginiKevin MacDonald - Thinking About Neoconservatismwhitemaleandproud100% (1)

- Social Studies Teaching StrategiesDocument12 paginiSocial Studies Teaching Strategiesapi-266063796100% (1)

- Wheelen Smbp13 PPT 10Document27 paginiWheelen Smbp13 PPT 10HosamKusbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biome Summative AssessmentDocument2 paginiBiome Summative Assessmentapi-273782110Încă nu există evaluări

- Small Sided Games ManualDocument70 paginiSmall Sided Games Manualtimhortonbst83% (6)

- Should Students Who Commit Cyber-Bullying Be Suspended From School?Document2 paginiShould Students Who Commit Cyber-Bullying Be Suspended From School?LucasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 7 Summative AssessmentDocument2 paginiChapter 7 Summative Assessmentapi-305738496Încă nu există evaluări

- Bridge Team ManagementDocument75 paginiBridge Team ManagementSumit RokadeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Althusser's Marxist Theory of IdeologyDocument2 paginiAlthusser's Marxist Theory of IdeologyCecilia Gutiérrez Di LandroÎncă nu există evaluări

- mghb02 Chapter 1 NotesDocument1 paginămghb02 Chapter 1 NotesVansh JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kenya HRH Strategic Plan 2009-2012Document72 paginiKenya HRH Strategic Plan 2009-2012k_hadharmy1653Încă nu există evaluări

- Ok Teaching by Principles H Douglas Brown PDFDocument491 paginiOk Teaching by Principles H Douglas Brown PDFUser PlayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Skills Rating SystemDocument12 paginiSocial Skills Rating Systemapi-25833093460% (5)

- IHRM Chapter 1 IntroductionDocument23 paginiIHRM Chapter 1 Introductionhurricane2010Încă nu există evaluări

- Bound by HatredDocument235 paginiBound by HatredVenkat100% (1)

- Adm. Case No. 5036. January 13, 2003. Rizalino C. Fernandez, Complainant, vs. Atty. Dionisio C. Esidto, RespondentDocument50 paginiAdm. Case No. 5036. January 13, 2003. Rizalino C. Fernandez, Complainant, vs. Atty. Dionisio C. Esidto, RespondentCess Bustamante AdrianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nuri Elisabet - 21180000043Document3 paginiNuri Elisabet - 21180000043Nuri ElisabetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elizabeth F Loftus-Memory, Surprising New Insights Into How We Remember and Why We forget-Addison-Wesley Pub. Co (1980) PDFDocument225 paginiElizabeth F Loftus-Memory, Surprising New Insights Into How We Remember and Why We forget-Addison-Wesley Pub. Co (1980) PDFAbraham VidalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Creative Writing Techniques for Imagery, Figures of Speech, and DictionDocument2 paginiCreative Writing Techniques for Imagery, Figures of Speech, and DictionMam U De Castro100% (5)

- The Self From Various Perspectives: SociologyDocument8 paginiThe Self From Various Perspectives: SociologyRENARD CATABAYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Explain The Barrow's Three General Motor Fitness Test in DetailDocument4 paginiExplain The Barrow's Three General Motor Fitness Test in Detailswagat sahuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Towards Interactive Robots in Autism TherapyDocument35 paginiTowards Interactive Robots in Autism TherapyMihaela VișanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beauty FiltersDocument1 paginăBeauty FiltersshruthinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychiatric Interview Professor Safeya Effat: I History Taking 1. Personal DataDocument4 paginiPsychiatric Interview Professor Safeya Effat: I History Taking 1. Personal DataAcha Angel BebexzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Training RegulationDocument21 paginiTraining Regulationvillamor niez100% (2)

- STS Intellectual-RevolutionDocument17 paginiSTS Intellectual-RevolutionLyza RaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Entrepreneurial Strategy: Generating and Exploiting New StrategiesDocument20 paginiEntrepreneurial Strategy: Generating and Exploiting New StrategiesAmbika Karki100% (1)

- Syllabus Division Primary Classes of AJK Text Book Board by Husses Ul Hassan B.Ed (Hons) Govt P/S Nagyal Tehsil &distt MirpurDocument48 paginiSyllabus Division Primary Classes of AJK Text Book Board by Husses Ul Hassan B.Ed (Hons) Govt P/S Nagyal Tehsil &distt MirpurMuhammad NoveedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Measuring Individuals’ Misogynistic Attitudes Scale DevelopmentDocument42 paginiMeasuring Individuals’ Misogynistic Attitudes Scale DevelopmentReka Jakab-FarkasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spin Master Toronto Interview Guide: Click Here To Enter Text. Click Here To Enter Text. Click Here To Enter TextDocument3 paginiSpin Master Toronto Interview Guide: Click Here To Enter Text. Click Here To Enter Text. Click Here To Enter TextRockey MoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRM Questionnaire ResultsDocument8 paginiCRM Questionnaire ResultsAryan SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Be a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooDe la EverandBe a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsDe la EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (1422)

- For the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityDe la EverandFor the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (56)

- Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat PhobiaDe la EverandFearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat PhobiaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (112)

- Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its LegacyDe la EverandRiot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its LegacyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (13)

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryDe la EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (14)

- Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,De la EverandBound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (69)

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsDe la EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (386)

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsDe la EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (16)

- Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleDe la EverandSomething Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (34)

- Summary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDe la EverandSummary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- White Guilt: How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights EraDe la EverandWhite Guilt: How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights EraEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (43)

- Say It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyDe la EverandSay It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (18)

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusDe la EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (22)

- Feminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionDe la EverandFeminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (89)

- O.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It: The Shocking Truth about the Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron GoldmanDe la EverandO.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It: The Shocking Truth about the Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron GoldmanEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (2)

- Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageDe la EverandWordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (82)

- Walk Through Fire: A memoir of love, loss, and triumphDe la EverandWalk Through Fire: A memoir of love, loss, and triumphEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (71)

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesDe la EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (70)

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateDe la EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (18)

- The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, 10th Anniversary EditionDe la EverandThe New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, 10th Anniversary EditionEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (1044)

- The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row (Oprah's Book Club Summer 2018 Selection)De la EverandThe Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row (Oprah's Book Club Summer 2018 Selection)Evaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (231)

- Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityDe la EverandGender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (317)

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveDe la EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (22)

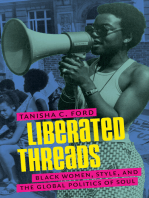

- Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of SoulDe la EverandLiberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of SoulEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Family Shepherds: Calling and Equipping Men to Lead Their HomesDe la EverandFamily Shepherds: Calling and Equipping Men to Lead Their HomesEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (66)