Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Comparative Advantage and Competitiveness

Încărcat de

Kookoase KrakyeDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Comparative Advantage and Competitiveness

Încărcat de

Kookoase KrakyeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Declaration

I do hereby declare that except for references to other peoples works which have

been duly acknowledged, this thesis presented is my own and has not been written

for me, in whole or in part by any other person(s).

Isaac Fokuo Donkor,

isaacfdonkor@gmail.com

November, 2008

UNIVERSITT HOHENHEIM

The Determinants of Competitiveness and Performance of

Ghanas Key Non-Traditional Exports

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award

of a degree of master in Agricultural economics

by

Donkor, Fokuo Isaac

Institute for Agricultural Policy and Agricultural Markets

Chair, Agricultural and Food Policy

University of Hohenheim,

Stuttgart, Germany

Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Harald Grethe, Prof. Dr. Tilman Becker

November, 2008

The Thesis Committee for Universitt Hohenheim

certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis:

The Determinants of Competitiveness and Performance of Ghanas

Key Non-Traditional Exports

Approved By

Supervising Committee:

Supervisor:

(Prof. Dr. Harald Grethe)

(Prof. Dr. Tilman Becker)

Dedication

To my Parents George K. Donkor and Comfort Donkor

i

Acknowledgement

I am thankful to the Almighty God for all his protection throughout this journey. To

God be the glory for the great things He has done in my life up to date.

I wish to express my heartfelt thanks to Prof. Dr. Harald Grethe for believing in me and

opening his door to me anytime. His thoughtfulness, advice and insight shaped the final

outcome of this thesis. To Eckhard Volkmann, my former boss at GTZ, I am most

grateful for your kindness. You are second to none. My sincere gratitude also goes to

Katja Glause and Anna J ankowski for taking time to help shape the thesis. The thoughts

and direction of the thesis was in part owed to my internship at the South Centre in

Geneva. To Darlan, Luisa Bernal and Zeeshan, Marumo, Nicole, Angela, Wase and

Heather, I say thanks a lot.

Secondly, I am forever, indebted to the friendship of Patience Tinashe Shoko. You will

forever remain my friend. To Sheila, I say thanks for being there. And to all my

Ghanaian colleagues in Hohenheim; J oseph, Seth, Richard, Akwasi, Augustine, Moro

and Carl I say Ayekoo. To Henry Lubinda, Nina Koch, Franziska Harich, Rohan Orford

and Samuel Boama I say hi-five buddies.

Finally, to Katrin Winkler, the Coordinator of the Agricultural Economics program of

the University of Hohenheim, you are the best.

ii

Abstract

The Determinants of Competitiveness and Performance of Ghanas

Key Non-Traditional Exports

By

Donkor, Fokuo Isaac (M.Sc.)

Universitt Hohenheim, Stuttgart, 2008

SUPERVISOR: (Harald Grethe)

Global trade has expanded, even as, conventional barriers to trade continue to decline.

At the same time, the continual decline in the value of primary commodities on the

international market is subjecting many developing economies, including Ghana, with

small export portfolios into fiscal difficulties. The need for product and market

diversification in an increasingly competitive trading regime becomes imperative.

The paper examines Ghanas diversification drive in the export sector over the past

decade. Specifically, it analyses for performance and competitiveness in its production

and exports of ten product lines not included in its traditional exports basket of raw

cocoa beans, and timber in the agro-forestry sector. Referred to as non-traditional

exports, they are products not forming part of the customary diets of its people and are

mainly produced for their cash values through exports, such as; fresh pineapples,

preserved fruits, cashew and Shea nuts, as well as, those resulting from vertical and

horizontal diversification of its traditional exports including; cocoa butter, cocoa paste,

preserved tuna, plywood and veneer.

Employing the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) and the Contribution to Trade

Balance (Lafay), indices as proxies for the level of specialization and thence a measure

of competitiveness, the following observations were made: that cocoa paste and

plywood are most competitive non-traditional exports from Ghana followed closely

cocoa butter and veneer. Cashew nuts and fresh pineapples revealed positive

comparative advantages and Lafay indices at marginally reduced levels whilst preserved

fruits and frozen tuna revealed not specialization. Preserved fruits revealed de-

specialization. There was no data for Shea nuts.

iii

The general conclusion was that non-traditional exports emanating from endowed

traditional export baskets like cocoa beans (cocoa butter and paste) timber (veneer and

plywood) performed better averagely and are more competitive on the international

market (i.e. products that have undergone vertical diversification) than those existing as

stand-alone or novel products (horizontal diversification).

Key words: Non-traditional exports, Competitiveness, Diversification

iv

Table of Content

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I

ABSTRACT I

ACRONYMS V

LIST OF TABLES VII

LIST OF FIGURES VII

LIST OF GRAPHS/BOX VIII

CHAPTER I 1

1.1 RESEARCH TOPIC 1

1.2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVE 4

1.3 ORGANIZATION OF THESIS 4

CHAPTER II 5

2.1 BRIEF OVERVIEW OF GHANAS ECONOMY 5

2.1.1 GHANAS EXPORT PERFORMANCE 2002-2006 6

2.1.2 GROWTH TRENDS AND DIRECTION OF EXPORTS 7

2.1.3 MAJ OR EXPORT DESTINATIONS AND THEIR SHARE OF EXPORTS 8

2.2 NON-TRADITIONAL EXPORTS (NTES): CONCEPTS AND DEFINITIONS 9

2.3 DETERMINANTS OF EXPORT PERFORMANCE AND COMPETITIVENESS 12

2.3.1 THE THEORY OF THE FIVE COMPETITIVE FORCES 13

2.3.2 BARRIERS TO ENTRY 14

2.3.3 RIVALRY AMONG EXISTING COMPETITORS 14

2.3.4 SUBSTITUTES 16

2.4 OTHER FACTORS THAT AFFECT EXPORT PERFORMANCE AND

COMPETITIVENESS 17

2.4.1 THE EFFECT OF PREVIOUS PERFORMANCE 17

2.4.2 DIVERSIFICATION 18

CHAPTER III 20

3.1 METHODOLOGY 20

3.2 COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE 20

3.3 LAFAY INDEX 21

3.4 DATA REQUIREMENTS AND SOURCES 23

v

CHAPTER IV 24

4.1 RESULTS 24

4.1.1 DISAGGREGATION OF GHANAIAN EXPORTS 24

4.1.2 APPROXIMATION OF COMPETITIVENESS: THE SYMMETRIC REVEALED COMPARATIVE

ADVANTAGE (SRCA) 25

4.2 NORMALIZED COMPETITIVENESS MEASURE: THE LAFAY INDEX 25

CHAPTER V 30

5.1 DISCUSSION OF RESULTS 30

5.1.1 COCOA INDUSTRY 30

5.1.2 TIMBER INDUSTRY 32

5.1.3 THE PINEAPPLE AND PRESERVED FRUITS INDUSTRIES 33

5.1.4 NUTS INDUSTRY 37

5.1.5 THE FISHERY SECTOR 38

5.2 POTENTIALLY COMPETITIVE EXPORTS 40

CHAPTER VI 42

6.1 OPTIONS FOR INCREASING COMPETITIVENESS 42

APPENDIX 47

BIBLIOGRAPHY 54

Acronyms

AGOA Africa Growth and Opportunity Act

CAPEAG Cashew Processors and Exporters Association

CDC Cashew Development Center

CEPII French Economic Research Institute

CMC Cocoa Marketing Commission

COCOBOD Market Board

CPC Cocoa Processing Company

vi

CRIG Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana

CTB Contribution to Trade Balance

ECOWAS Economic Community of West Africa

EEC European Economic Community

EPAs Economic Partnership Agreements

EU European Union

EUREPGAP European Good Agricultural Practices

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN

GAP/IPM Good Agriculture Practices/Integrated Pest Management

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GEPC Ghana Export Promotion Council

GNPC Ghana National Procurement Agency

GPRS II Ghana Poverty reduction Strategy II

GSP+ Generalized Systems of Preference plus

GTZ-MOAP German Technical Cooperation- Market Oriented Agriculture

Program

HS Harmonized System of Classification

IMF International Monetary Fund

ISO International Standard Organization

ITC International Trade Centre

LBCs Licensed Buying Companies

MOF Ministry of Fisheries (Ghana)

MOTI/PSI Ministry of Trade and Industry and President Special Initiative

(Ghana)

NTE Non-Traditional Export

PPRC Producer Price Review Committee

vii

RCA Revealed Comparative Advantage

RSCA Revealed Symmetric Comparative Advantage

TIPCEE USAID Trade and Investment Program for Competitive Export

Economy

TRADEMAP Trade Interactive Map of ITC

UNCTAD UN Conference on Trade and Development

WTO World Trade Organization

List of Tables

Table 1: Top Performing NTEs From Ghana in 2006........................................................ 3

Table 2: GDP Structure based on Main Economic Activities between 2000-2004 (in %) 6

Table 3: Rank of major importing markets for products exported by Ghana..................... 8

Table 4 Leading Cashew exporters and Unit Price Differential based on Processing

(2006)................................................................................................................................ 16

Table 5: Major products exported by Ghana (2006)......................................................... 24

Table 6: Revealed Symmetric Comparative Advantage (RSCA)..................................... 25

Table 7: Lafay Index of Ghanaian Top-performing NTEs (2006) ................................... 26

Table 8: Lafay Index of Major Exporters of NTEs exported by Ghana (2006). .............. 28

Table 9: World Imports of Cocoa and Cocoa Products (2002-2006)............................... 31

Table 10: Number of Marine Fishing Vessels in Ghana.................................................. 39

Table 11: Potential NTE Basket for Ghana (Lafay Index , 2006).................................... 40

List of Figures

Figure 1: The Five Competitive Forces that Determines Industry Profitability (Porter,

1990)................................................................................................................................. 13

viii

List of Graphs/Box

Box 1: Adapting To Changing Market Preference: Buyer Driven Approach........ 36

Graph 1: Major Cashew Producers (2006). ...................................................................... 15

Graph 2: Market Share of Major Cocoa Importing Countries in 2006 (%)...................... 32

Graph 3: Main Export Destinations of Ghana Fresh Pineapples (2006). ........................ 35

Graph 4: Growth trends in Potential NTEs on the International Market (2003-2006)..... 41

1

1CHAPTER I

1.1 Research Topic

Global trade has expanded steadily in the past decade as a result of a more formalized

trading regime across countries at both the bilateral and multilateral levels (World

Economic Outlook, 2007). For many developing countries therefore, it has become

imperative that they are positioned to take advantage of existing, as well as, new

opportunities arising from the development of global markets and trade negotiations,

even as, conventional barriers to trade continue to decline. Many developing

countries foreign receipts from trade have for decades been accrued to the

production and exports of primary commodities with minimal vertical diversification

(Barghouti et al., 2004). Over time, the value of primary commodities has declined

on the international market, subjecting many developing economies with small

export portfolios into fiscal difficulties (Radetzki, 2002). The need to diversify their

production horizontally

1

and vertically at a more competitive level has become

essential to developing countries including Ghana.

Ghanas economy, for many decades since its independence, has relied heavily in the

production and exports of its naturally-endowed primary commodities including

cocoa, gold and timber. However, as a result of many factors including loss of market

share to more competitive producers

2

, there have been concerted efforts over time to

1

Horizontal diversification refers to the process of entering into the production of new lines

within a particular product sector. For example commercial production of pineapple in the

fruits and vegetable sector constitute a horizontal diversification. On the other hand

commercial processing of pineapple into pineapple juice, jam etc. constitute vertical

diversification.

2

Ghana was more competitive when the production and exports of these primary

commodities were heavily dependent on labour and prevailing natural conditions which well

suited production. With the advent of improved technology for example in the mining

sectors, more endowed countries are able to produce more minerals for exports

competitively. Improved R&D in the late 1980s turned the production of cocoa into a capital

intensive business even as supply surge therefore depressing world market prices.

2

shift production into innovative sectors that favours the natural and human

endowment of the economy. The shift has been promulgated in two folds:

vertically by moving up the production chain for a particular sector mainly in the

form of continuous product development and horizontally by entering into

production areas within a particular sector hitherto unexploited commercially.

Products emanating from this form of venture are the so-called non-traditional not

least because these products are novel in terms of their commercial exploitation

(Singh, 2002).

Many developing countries endowed with certain climatic conditions have taken

advantage of the increased demand for out-of-season food crops by consumers in the

temperate regions to produce those crops mainly for exports with considerable

returns on such investments. These crops commonly referred to as non-traditional, is

defined by Singh (2002) as crops and products that are not part of the customary diet

of the local populations and are grown primarily for their cash values and export

potential. For many African countries engaged in the production and export of non-

traditional products, the European Economic Area remains the most lucrative market

where these countries enjoy not only a considerably enhanced market access, but

sustained consumer demand for those products exported by them albeit under strict

quality and safety controls (Dolan, and Humphrey, 2000).

Studies have consistently shown that the continuing deterioration in the terms of

trade of developing countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan regions traditional exports

is offset, among other measures

3

, by shift to non-traditional activities (Helleiner, G.

K. 2002; Dolan, C., J . Humphrey, 2000 and C. Harris-Pascal. 1999). The potential

therefore, of non-traditional exports (NTEs) to developing countries, including

Ghana, cannot be overemphasized.

For any country (or firm) to enter into a particular market, the onus lies on its ability

to identify commercially viable venture which is able to compete given a set of

endowments and constraints (Rauch, 1999). The Ghana Export Promotion Council

3

Other factors that offset deterioration in terms of trade include efficient import substitution,

policy-related measures etc.

3

(GEPC) is the trade promotion arm of the Ministry of Trade and Industry tasked with

facilitating the development and promotion of Ghanas non-traditional exports. It

seeks to achieve its set objectives through the provision of development initiatives

including market penetration assistance, capacity building and information delivery

to exporters. The GEPC is additionally tasked with identifying potential products for

exports. It produces a list of products which is reviewed every 3 to 5 years on

performance.

The GEPC identifies the following ten products as the countrys top-ten performing

non-traditional exports as of 2006:

Table 1: Top Performing NTEs from Ghana in 2006.

PRODUCT

GROUP

NUTS HORTICULTURL

PRODUCTS

MARINE

PRODUCT

S

MANUFACTURED

PRODUCTS

Cashew

nuts

Fresh Pineapple Frozen

Tuna

Cocoa Paste

Shea Nut Preserved Fruit Prepared

Tuna

Cocoa Butter

Veneer Sheet

Plywood

Source: GEPC, 2006.

The UN Commission on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the World Trade

Organization (WTO) identifies the lack of technical capacity on the part of many

developing countries in identifying and prioritizing potential production and export

sectors of their economy. As a result these organization have been collaborating

through a joint effort, the International Trade Centre (ITC) to assisting developing

countries identify potential export sectors, as well as, with information in the

formulation of enabling trading regime by the provision of market development

tools, trade statistics information and market contacts. The GEPC receives such

support from the ITC in this regard. GEPC relies almost entirely on the use of the

ITC trade research tools in identifying potential sectors and products for exports. On

casual inspection, it is not clear what indicators were used to identify these products

and question arise as to why certain products are missing from the list of potential

products especially when they are deemed to be top performing products on the

international market. Also, the list provides little information regarding the prevailing

4

domestic conditions and how these conditions might play in the export performance

and competitiveness dynamics.

1.2 Research Objective

This thesis as its main objective, therefore, tries to identify a set of indicators of the

export performance of the listed products using the information provided by the ITC.

It empirically applies the theory of comparative advantage and specialization

(modified as a proxy for competitiveness) using set of trade data from the ITC to test

the export performance of the so-called top ten NTEs of Ghana. Finally, these

indicators are used to identify alternative potential non-traditional products for

exports.

In order to arrive at the set objective, the paper will attempt to provide answers to the

following questions:

1. Are these products non-traditional? What accounts for their categorization?

2. What are the main indicators of export performance and how are they

different from that of competitiveness?

3. What are the measurable and non-measurable factors affecting export

performance and competitiveness?

4. Which products are deemed as performing well and which are not. What

should be included as potential NTE?

1.3 Organization of Thesis

The paper is organized in four sections. Section 1 justifies the choice of topic for

research and outlines the objectives and expectations of the thesis. Section 2 reviews

the theoretical framework in which the research will be carried out. The goal is to

discuss available literature on factors that influence performance and competitiveness

in the context of non-traditional exports. Section 3 explores the methods of research

by provision of the theoretical background for these methods. It explains the source

of data and the shortcomings in its use. Analysis of results including calculations of

the indices of export competitiveness, as well as, discussions of the underlying

elements influencing these outcomes are detailed in Sections 4 and 5 respectively.

Conclusions, summarizing the various sections of the thesis are provided in

Section 6.

5

2CHAPTER II

This chapter forms the conceptual and theoretical framework in which the analysis

for the thesis will draw from. It is divided into three sub-sections: First, a general

economic overview of Ghana, including the export structure, growth patterns and

export destinations is provided. Second, products and sectors that constitute non-

traditional exports in the wider context are reviewed and thence the various

classifications of NTEs are analysed as per the role NTEs play in the economies of

developing countries. The last sub-section reviews some of the determinants of

competitiveness drawing largely on, Michael Porters five forces of competitiveness

proposition. Other factors such as effect of previous performance and diversification

are also discussed.

2.1 Brief Overview of Ghanas Economy

The Ghanaian economy with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per Capita of US$

520, growing at an annual average of 5.7 per cent, has experienced noticeable gains

in its macroeconomic indicators in the medium term, with for example, an annual

inflationary rate of 14.6 per cent in 2006 compared to 27.1 per cent in 2000 (The

World Bank, 2006). Industrial activities, mainly mining and construction, (5%) and

services sectors including transportation and the financial services (4.7%) lag behind

agriculture (6%) in their contribution to annual GDP growth (GPRSII, 2006). Crops

and livestock production, cocoa sub-sector, forestry and fishing are the most

important agricultural activities contributing over 37 per cent to total GDP in 2004

(see Table 2). Despite the relative strength of the agricultural sector to the rest of the

economy, it remains underdeveloped and marginally financed. The government in its

poverty reduction strategy survey, GPRS II concedes that

the stagnation of technologies and in some areas, the wide gender inequalities in

access to and control over land and agricultural inputs, including extension services,

as well as adverse environmental factors such as climate variability and land/soil

degradation, continue to be challenges posed to the growth potential of the

agricultural sector(GPRS II, 2006).

6

Ghanas total export in value in 2006 was approximately US$ 3.6 billion down 35%,

from the 2005 value of US$ 5.6 billion. Imports by Ghana exceeded its exports by

US$ 1.7 billion during the same period in 2006. According to the International

Monetary Fund IMF, 2006) decline in the prices of the countrys major commodities

gold, and cocoa on the world market accounted for the countrys dismal performance

in 2006. Despite that, medium term exports grew at 28 per cent between 2002 and

2006 (ITC, 2006).

Table 2: GDP Structure based on Main Economic Activities between 2000-2004 (in %)

Economic Sector 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Agriculture 35.27 35.24 35.15 36.38 37.94

Crops And Livestock 22.01 22.25 22.43 22.35 22.12

Cocoa Sub-sector 4.81 4.58 4.36 5.77 7.60

Forestry & Logging 3.89 3.92 3.94 3.95 3.98

Fishing 4.57 4.49 4.42 4.30 4.24

Industry 25.40 25.22 25.28 25.10 24.74

Mining & Quarrying 4.98 4.72 4.72 4.68 4.59

Manufacturing 9.02 9.00 9.03 8.94 8.75

Electricity & Water 2.69 2.70 2.69 2.66 2.59

Construction 8.71 8.79 8.83 8.79 8.8

Services 28.82 29.16 29.21 28.94 28.65

Transport, Storage & Communication 4.29 4.36 4.41 4.41 4.44

Wholesale, Retail Trade Restaurants & Hotels 6.72 6.80 6.87 6.82 6.81

Financial & Business Services and Real Estate 4.26 4.28 4.32 4.30 4.29

Government Services 10.06 10.17 10.08 9.92 9.69

Community, Social & Personal Services 2.56 2.62 2.62 2.58 2.56

Producers Of Private Non-private Services 0.94 0.93 0.92 0.90 0.87

Net Indirect Taxes 10.51 10.38 10.36 9.14 8.66

Source: Ghana Statistical Services (cited in GPRS II), 2006.

2.1.1 Ghanas Export Performance 2002-2006

Improved and sustained export performance is a key to Ghanas economy. The

contribution of trade to its total GDP remains substantial. However, the extent

of development of the sector is dismal. According to Aryeetey and McKay

(2004), until the turn of the 21st Century, Ghanas external trade sector

experienced minimal changes with insignificant growth in its export

composition. The country relied heavily on its major traditional export

products; cocoa, timber and minerals (including gold, diamond bauxite and

manganese) which were susceptible to negative price development over that

period. This assertion is agreed by Frimpong-Ansah and J onathan (1991) who

observed that the share of exports to GDP declined significantly from the late

7

1960s until the early 1980s, associated with sharp decline and disinvestment

in the cocoa sector and a strong anti-export bias in policies. Between 1977

and 1983, the economy experienced structural difficulties as a result of

political instabilities.

4

However, the economy recorded some modest gains

from the institutionalization of IMF/World Bank sponsored policies such as

the Economic Recovery and the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAP) in the

late 1980s. The measures stipulated under the SAP included policies that

sought to reform the cocoa and gold sectors including subscription to more

liberal trade and fiscal policies. Again, attention was given to improving the

countrys participation in the export of non-traditional products. These NTEs

are mostly agricultural or processed agricultural products, including

pineapples, yams, wood products, cocoa products, canned tuna and oil palm

products. From 1989 to 1996 earnings from non-traditional exports increased

from US$23.8 million to US$276.2 million. This new trend has continued and

in 2003 the sub-sector brought in $588.9 million (Aryeetey and McKay,

2004).

2.1.2 Growth Trends and Direction of Exports

Ghana exported US$ 3.6 billion of merchandise in 2006, at rate above the world

average of 17 per cent per annum, between 2002 and 2006. However, short-term

growth in value of its exports declined by approximately 35% between 2005 and

2006 mainly as a result of unit price fall in its major traditional exports of cocoa (

which accounts for over 34% of total exports), precious stones and mineral (32%)

and timber (8%). For example between 2005 and 2006, 11 of the countrys top-20

export products experienced a decline in their export value between 2005 and 2006

cumulating in an average short-term growth of -35 per cent in 2006 (ITC, 2006).

Ghanas share of world merchandise export is 0.03 per cent.

4

The country between these periods was under military dictatorship. Political power shifted

hands amongst 3 separate regimes. It is important to note also, that, poor climatic conditions

affected the mainly rain-fed agricultural production in the early 1980s resulting in massive

famine in 1983.

8

2.1.3 Major Export Destinations and Their Share of Exports

The European Union (EU) remains Ghanas most important export market. . Ghanas

trade with the EUat 65% of total traderemains the largest compared to anywhere

in the world According to trade theories, colonial ties play a major role in how and in

what countries trade (Rauch, 1999). The countries of sub-Saharan Africa including

Ghana have had a long standing relationship with many of the EU countries

including the United Kingdom, France and Belgium who incidentally remain the

major trade partners of Africa. Again, the establishment of regional trade agreements

between developing and least developed countries of the southwith colonial ties to

Europehas helped facilitate trade between the two blocs. The Economic

Partnerships Agreements (EPAs) between EU and the group of Africa Caribbean and

Pacific countries is an example of such initiative that promote trade between these

two blocs by the provision of preferential treatments. Table 3 provides an overview

of the major destinations of Ghanas export between 2003 and 2006. Europe has had

a strong and sustained presence in Ghana. However, South Africa has become

important market for the countrys export growing in value from US$87 million in

2003 to just US$100million shy of a billion in 2006. Exports to big markets such as

the United States of America and India have also experienced some modest growth

even though they have been sporadic; the former as a result of the introduction of the

African Growth and Opportunity Act aimed at improving selected developing

economies participation in the United States market. From US$67m in 2003, total

exports from Ghana to the U.S. recorded a value of US$1.8billion in 2005.

Table 3: Rank of major importing markets for products exported by Ghana

Rank/Year 2003 2004 2005 2006

1 Switzerland

(25.7)

Netherlands

(25.4)

USA

(33.6)

South Africa

(25.8)

2 UK

(20.0)

UK

(13.5)

South Africa

(13.9)

Burkina Faso

(12.6)

3 Netherlands

(11.8)

Belgium

(7.3)

Belgium

(7.3)

Netherlands

(11.1)

4 Belgium

(4.9)

Free Zones

(6.8)

Nigeria

(7.7)

Switzerland

(6.8)

5 Germany

(4.8)

France

(6.2)

India

(6.4)

France

(4.6)

6 South Africa

(3.8)

South Africa

(6.0)

UK

(5.9)

Belgium

(4.0)

Source: ITC, 2006 (with own modifications).

9

2.2 Non-Traditional Exports (NTEs): Concepts and Definitions

The notion of what constitutes NTEs varies across countries, products and over time.

A country defines it traditional export based on its portfolio of commercially

successful exports over a time period. Diversification of its exports into new sectors

therefore, constitutes it non-traditional base. For instance, Singh (2002) defines non-

traditional crops as those that are not part of the customary diet of the local

population and are grown primarily for their high cash values and exports potentials.

Takane (2004) on the other hand emphasizes the relative relentless promotion of

exports of novel products against the more traditional stock of products as those

constituting its NTEs. Helleiner (2002) who has conducted extensive analyses on the

economic components of NTEs outlines four different factors that may influence

policy interest in NTEs as follows:

1. The hope of finding new export products that are not as vulnerable to

deteriorating terms of trade and/or declining world demand as are the

traditional bundle of exports (e.g. Delgado, 1995)

2. The hope that diversification in the export portfolio will reduce export

instability and, more broadly, risk; diversification may, for these purposes, be

achieved either through a new mix of products or via an expanded range of

markets (e.g. Alwang and Siegel, 1994)

3. The belief that certain new export products may generate greater dynamic

effects learning, positive externalities, etc. than traditional exports (e.g.

Wangwe, 1995; Ernst et al., 1998)

4. The prospect of exporting products that were previously producedwithin the

country but were not exported.

10

2.2.1 Classification and Categorization of NTEs

The concept of what constitute non-traditional will continue to vary depending on the

expectations of a policy, research or market study. Whilst the notion of dynamic

5

versus stagnant approach has been employed to classify traditional exports from non-

traditional (UNCTAD, 1996; Helleiner, 2002), NTEs have been classified by a

threshold percentage of export. The World Bank for example in its compendium of

development indicators (World Bank, 2004a: 2004b) defines NTEs as the ten

largest three-digit commodity groups in the countrys exports in the base year (1983

1984), unless those ten do not account for at least 75 per cent of those exports, in

which case more three-digit groups are added as necessary until at least 75 per cent is

reached. NTEs are, by implication, all of the rest (Helleiner, 2002). This is a

departure from earlier classifications that ascribed exports shares of less than 1 per

cent (Labys and Lord 1990), 2 per cent (Balassa, 1977) and 3 per cent (Balassa et al.,

1971 cited in Helleiner 2002). NTEs have also been defined by it newness in a

countrys production basket. By this definition, products are classified as non-

traditional by the fact that it had not hitherto been exploited commercially for

exports. This method however, conflict with products that are not in themselves new

but minor in the level of production and exports and hence might not necessarily be

novel (Singh 2002; Takane, 2004; Little and Dolan, 2000; Helleiner, 2002).

2.2.2 The Role of NTEs to Developing Economies

Proponents of theory of Export-led growth have argued on the premise that once

economic agents gain an advantage through the capture of export markets, it tends to

sustain that advantage through the operation of various cumulative forces which

generates a so-called virtuous circles for favoured economic agents (Thirwall,

2003). Externalities are therefore, generated, as a result, in the non-export sectors of

the economylearning effects, increased investment, improved infrastructure and

5

Dynamic products are those with both the most rapidly increasing OECD import demands

and an increasing share in OECD imports, while the most stagnant products are those with

both lower rates of growth in OECD demand and a declining share therein (Helleiner, 2002).

11

productivity etc.which drive the entire economy (Helleiner, 2002). By implication,

when economic agents fail to take advantage of such export opportunities, it leads to

the creation of vicious circles with attending negative externalities. In the case of

developing countries, their performance in the production and exports of their

traditional products put them in the second category (J ebuni et al., 1992; UNCTAD,

1998; Grossman and Helpmann, 1991). Helleiner (1998) argues for example that,

with the exception of South Africa and Mauritius, most African countries have not

maximised the positive externalities associated with their exports on their economies.

Traditional exports, more often, have narrow economic participants on their

production chain and without appropriate interventions, the growth and development

are accruable only to economic agents operating in that sector alone. Helleiner (2002)

classifies such production processes with limited or de-linked developmental effects

as being staticwith low productivity, low investment etcand hence continued

deterioration in the terms of trade of such economies and argues a shift to NTE with

dynamic effects as the key to larger economy-wide effect. The horticultural

industry has long been touted as one of such dynamic sectors with wider

development secondary effects. A study by McCulloch and Ota (2002) asserted that

households that participated in horticulture in rural communities sampled earned a

comparatively higher income than those that did not with women being the main

earners.

The success of pioneering non-traditional agricultural exporters such as Kenya, South

Africa and Guatemala have variously been cited in literature to promote the

development and replication of the sector in other developing countries. In an

example, von Braun, (1994) reported that the production of export vegetables created

new employment opportunities, reduced the need to rely on uncertain off-farm

employment, and increased the household incomes of the smallest Guatemalan

farmers (Singh, 2002). In Bhutan, the production and exports of high-value products

such as Masutake mushroom and lemon grass oil to J apan and Europe, respectively

have consolidated the countrys niche market in these product sectors and as Tobgay

(2005) emphasizes, despite the relatively high cost of transport of the products to

these market, the relatively respectable returns have ensured the growth of the

12

sectors. In many developing countries, horticulture which is a key NTE sector

currently accounts for 20 per cent of world agricultural exports (UNCTAD, 2008).

The relatively low cost of labour and favourable natural resource endowments in

many developing countries confers them with comparative advantage in that sector

(Okello, 2004 cited in UNCTAD, 2008) aside the good prices that it offers compared

to traditional exports which have experienced price decline over time. According to

the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2006) the fishery

sector presents export opportunities for many coast-lying developing countries

because fish stocks in most high-consuming developed countries have depleted even

as their demand continue to grow.

2.3 Determinants of Export Performance and Competitiveness

This section examines the theoretical background that explains patterns of exports

from across countries in todays increasingly competitive market. Numerous theories

explain the differences in pattern of trade, export performance and competitiveness

across countries and economic blocs including; the Ricardian model that points to

technological differences as the source of comparative advantage (Leamer and

Lundborg, 1993). On the other hand Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson theory of

comparative advantage reflects on the supplies of productive inputs (existence of

factor endowments) as the main source of comparative advantage and yet the

Chamberlainian school of thought (including Krugmans New Trade Theory)

(Eszterhai, 2007) refers to the existence of economies of scale and prevailing market

structure as the main sources of competitiveness. Whilst this thesis is not the

platform to discussing the merits or otherwise of these various theories, the thesis

chooses to rely heavily on Michael Porters so-called five-forces of competition

theory (Porter, 1990) in explaining the pattern of exports with respect to the topic

under discussion.

The fundamental insight of Porters theory is that national prosperity is created, not

inherited (Porter, 1990) thereby refuting, in the process, the traditional economic

theory that variables like labour costs, interest rates, and economies of scales are

most elemental to explaining a nations competitive advantage (Helvik and

Harnecker, 2005). It is important to keep in mind that nations by themselves do not

13

initiate trade; it is the done by individuals and individual firms within nations and

therefore, Porters model which is an industry-level framework with the nation as

its core unit of analysis becomes important in capturing the elements of export

patterns at the national level without losing sight of the importance the individuality

of firms.

2.3.1 The Theory of the Five Competitive Forces

Figure 1: The Five Competitive Forces that Determines Industry Profitability (Porter, 1990).

Figure 1 illustrates the five competitive forces that determine industry profitability as

espoused by Michael Porter in his book Competitive Strategy published in 1980. In

it, he argued that the essence of formulating competitive strategy is relating a

company to its environment (11, p.3). The environment, he argued, results from

historical activities and traditions, factors which are inherited rather than created.

In order for firms to counter (or to take advantage of) the effects of the existing (or

pre-existing environment), strategies need to be created and hence his assertions

that prosperity is created. Porter details the forces of competition as follows:

Potential Entrants

Suppliers Buyers

Substitutes

Industry

Competitors

Rivalry among

Existing Firms

Bargaining Power of

Suppliers

Threat of New Entrants

Bargaining Power of

Buyers

Threat of Substitute

Products/Services

14

2.3.2 Barriers to Entry

Industries whilst facing barriers to entry, must compete for buyers, ward off potential

entrants/substitute products and bargain for the least cost supply at any given

business cycle. The success of any single industry therefore, is how it is able to relate

to these competing forces continuously. Porter considers barriers to entry to include

economies of scale, product differentiation, capital requirements, switching costs,

access to distribution channels, cost disadvantages independent of scale, government

policy and expected retaliation. For example the fruits processing industry in Ghana

faces significant entry barriers into the European market not least because as a

relatively capital intensive market, most EU member countries are themselves

producers and need to protect their industries (Hummels and Klenov, 2005). Whilst,

conventional barriers to exports of fresh fruits to the EU has substantially been

reduced, processed fruits juices not only face tariff escalation but also a more

stringent safety and quality standard. Hallack and Schott in 2005 estimated the

relationship between per capita income and aggregate demand for quality. He

observed that rich countries tend to import relatively more from countries that

produce high-quality goods (as had long been argued by Linder in 1961). The

capacity to penetrate these markets while addressing these concerns, therefore, is

essential to developing countries Fruit products that undergo vertical diversification

are especially subjected to stringent quality management procedures (from ISO

9001:2004 to HACCP) to provide quality assurance to an increasingly powerful

consumer in the supplier-consumer relationship (Anderson and Nielsen, 2001). The

EU sets very high standards on pesticide use and its residual effect on processed

products. These measures reduce the competitive edge of producers from many

developing countries not least because they are capital intensive (especially private

standards such as EUREPGAP).

2.3.3 Rivalry among Existing Competitors

Secondly, existing competitors devise measures to secure market share, maintain or

expand their reach. The intensity of their rivalry depends on the balance of

competitors, industry growth, the size of fixed or storage costs, the amount of

differentiation or switching costs, the minimum size of investments, the types of

15

competitors, the strategic stakes and the size and types of exit barriers. Competition

affects a firms performance in two-fold; performance resulting from its exposure to

the domestic market and that to the foreign market (Commander and Svejnar, 2007).

Secondly, the extent of the effect of competition on a firms performance is

dependent on the direction of product diversification. According to Herzer and

Nowak-Lehman (2006), under certain conditions

6

positive effects of increased

competition resulting from vertical diversification comes about from learning-by-

exporting, whilst, horizontal diversification may lead to improvements from

learning-by-doing

7

. However, Sachs and Warner (1997) warned that for producers

and exporters of primary products, these effects (learning-by-doing/exporting) may

not be significantly important in affecting performance.

Major Cashew Producers (2006)

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

V

i

e

t

n

a

m

I

n

d

i

a

B

r

a

z

i

l

N

i

g

e

r

i

a

I

n

d

o

n

e

s

i

a

T

a

n

z

a

n

i

a

C

o

t

e

d

'

I

v

o

i

r

e

G

u

i

n

e

a

B

i

s

s

a

u

M

o

z

a

m

b

i

q

u

e

B

e

n

i

n

Countr ies

P

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

(

1

0

0

0

M

T

)

Graph 1: Major Cashew Producers (2006).

6

On perfect market conditions, such as that firms are price takers, perfect competition etc.

7

Herzer et al year, page argues that if knowledge is generated through a systematic

learning process set off by exporting, developing countries will gain from orienting their

sectors towards exporting. Also exporters learn to diversify and improve their reach into

markets by gaining knowledge of their foreign buyers specifications, quality standards etc

which makes them (exporters) more competitive.

16

The cashew market presents a good example of how the amount of differentiation

affects the level of competition among rival producers. The unit value of cashew on

the international market is considerably dependent on the level of processing as

evident in Table 4. The 2006 average world price of shelled cashew was over

US$4400 per MT compared to US$619 when unshelled. Conversely, the major

suppliers of shelled cashew are notably absent in the unshelled cashew trade, even

more they tend to be net importers of that product as is the case of India which

imports substantial volume (88.04%) of unshelled cashew from Africa, including

Ghana. The Netherlands import a bulk of its shelled cashew from India and Vietnam

mainly to meet domestic demand, as well as, for re-exports to high value markets in

the EU. World exports of shelled cashew grew at 17 per cent between 2002 and 2006

even though supply dipped to -1 per cent between 2005 and 2006. On the other hand,

demand for unshelled cashew has not been healthy mainly because most importers of

the product are themselves producers and exporters and demand transmission in the

shelled cashew market is negatively magnified in times of poor demand. World

imports of unshelled cashew increased by 10 per cent in the medium term but fell by

11 per cent in the year leading to 2006.

Table 4: Leading Cashew exporters and Unit Price Differential based on Processing (2006).

Shelled Cashew Unshelled Cashew

Rank

Value of

Export

currency

Unit

Price(Per

MT)

currency

Value of

Export

currency

Unit Price

(Per MT)

currency

World 1,340,716 4,405 World 331,007 619

1 India 546,029 4,508 Cote d'Ivoire 91,331 619

2 Vietnam 380,985 4,236 Guinea Bissau 49,462 433

3 Brazil 187,538 4,338 Benin 48,520 707

4 Netherlands 106,943 4,982 Tanzania 35,633 647

5 Belgium 16,435 5,020 Mozambique 23,678 3,050

6 Tanzania 14,975 3,918 Ghana 8,881 328

Source: ITC (2006) with modifications.

2.3.4 Substitutes

Substitute products offer alternatives and limit the size of profits (REF). Porter

asserts that substitutes also depend on price and the ease of switching costs (REF).

Take the cocoa industry for example. Demand for chocolate and other food

preparations made from cocoa reached US$ 13 billion in 2006, exceeding the

17

previous year by more than US$500 million. Cocoa butter as the main ingredient

used in the production of chocolate and other cocoa-based confectionaries. Dand

(1999) asserts that whilst improved technology may extend the use of an expensive

material in production, the use of cheaper substitute for that material may also be

employed as a cost-reductive measure. The cocoa butter industry presents such

example. The relatively high unit cost of cocoa butter in the production of cocoa

confectionaries in the early 60s fuelled interest in research to find cheaper

substitutes cumulating the development of Coberine in 1960 by UNILEVER as a fat

for cocoa butter. Over the years, there has been growing interest in the development

of so-called Cocoa Butter Equivalents (CBEs) and Cocoa Butter Replacers (CBRs)

used at varying degree in the production of confectionaries albeit under strict

regulations. Dand, however, contends that how these substitute have impacted on the

competitiveness of cocoa butter remains unclear for several reasons: lack of data that

relates the relevant variables, substitution may be done for technical rather than for

economic reasons, the overall price of the product impact more on demand (and the

use of substitute may actually increase the consumption of cocoa).

2.4 Other Factors that Affect Export Performance and

Competitiveness

The factors that affect performance and competitiveness are not exhaustive.

However, many developing countries are engaged in the export of primary goods

and, their capacity to access information of niche markets, trends and growths of

products may be lacking. To such business agents, reliant on past performance is one

means of reading into the market and ultimately devising new competitive strategies.

Secondly, there is a gap between what is produced and exported from many

developing countries and the final products that is consumed from these initial

exports (REF). This section assesses how these two factors affect performance and

competitiveness.

2.4.1 The Effect of Previous Performance

Researchers acknowledge that there is no concrete theoretical framework for

investigating export performance (Leonidou, Katsikas and Samiee, 2002; Lages et al,

2004). Lages et al (2004) contends that researchers are more prone to studies that

18

desires and rewards theories that look for factors to improve performance and tend to

overlook firms reactive behaviour especially in retrospect. According to Cavusgli and

Nevin (1981), preceding export performance is likely to be positively related to a

commitment in the next period because export commitment is a function of resource

availability (Lages et al., 2004). They argued that when firms commitment to the

exporting venture increases as a result of positive past performance; they tend to

allocate more resources to that venture. For example, managers and employees will

be motivated to increase capital, production inputs and labour resulting from

increased wages etc. (they refer to these forces as the internal publics). Also,

improved past performance may stimulate growth in client numbers, interest from

credit institutions and suppliers of inputs (external publics). In the manufacturing

sector for example, Mauritius presents a good example of consistent improvements in

that sector. In 1980-90, Mauritius exported 48 per cent of her total exports as

manufactures but by 1995, it had increased its manufactured exports to 67 per cent

raising its per capita of manufactured exports from US$341 to US$823 (Teal, 1999).

Nonetheless, other researchers point out the possibility of the so-called fat cat

syndrome where past positive performance is associated with mediocrity and

relaxation of future commitments (Cyrert and March, 1963; Bourgeois, 1981; March

and Simon, 1958; Litschert and Bonham, 1978; cited in Lages et al., 2004).

2.4.2 Diversification

Another important element of export performance is diversification

8

.Hughes and

Oughton (1993) established two theoretical relationships between profitability and

diversification. They pointed to Williamson (1975) proposition that through greater

exploitation of a firms assets, reduction in transaction costs, and benefits that accrue

from economies of scope, diversification may be expected to increase profitability by

facilitating increased efficiency. Secondly, they argued that diversification

8

Market diversification entails shifting exports to new and more rewarding markets with

adequate adaptive capacity and long term expectation of sustained demand growth at lower

costs, whilst product diversification on the other hand include the expansion of the existing

export lines to cover more competitive goods and services.

19

strengthens firms recognition of their interdependence by increasing the number of

arenas which they meet and compete thereby providing greater scope for multi-

market contacts with the effect of reducing competition. However, Encaoua et al

(1986) who has extensively analyzed the relationship between diversification on

global market power (Hughes and Oughton, 1993) argued that diversification has a

two-way effect depending on whether the diversified firms produce substitute or

complement goods. Firms may choose to diversify their markets for several reasons

including to reduce their reliance on an increasingly monopolistic market (Dolan and

Humphrey, 2000), to improve their stake in price determination (Gereffi and

Korzeniewicz, 1994) and to find potential commercially viable markets (Minot and

Ngigi, 2004). The increasingly assertive role of EU supermarket chains, for instance,

in the horticulture market was a source of concern to many exporting developing

countries particularly, as prices were no longer a function of the primary produce

itself but more accruable to product differentiation through value addition in the

supply chain (Dolan and Humphrey, 2000; Humphrey, 2002; Gereffi and

Korzeniewicz, 1994; Gioe, 2006). According to Gioe (2006) in 1989, supermarkets

sold 33 per cent of fresh fruits and vegetables in the UK but by 1997, their share had

increased to 70 per cent. Many exporting countries responded to this development by

diversifying their exports to market where they could exercise more bargaining

power and control on prices whilst at the same time they concentrated on meeting

some new requirements and demands that influence prices such as standards,

traceability requirements and packaging (Minot and Ngigi, 2004). On the other hand

product diversification may be embarked upon mainly as a result of prevailing

market conditions. For instance, in the pineapple industry, consumers preference

shift from the traditional sweet cayenne variety to the MD2 on the European market

accounted for the shift in its commercial production across countries. Cote dIvoire

for example, a pioneering pineapple exporting country squeezed several competitors,

particularly Kenya and Ghana, out of business in the late 1980s on the EU market as

a result of it innovative-market-oriented-approach in that business (; Owen and Wood

1997 cited in Gioe, 2006).

20

3CHAPTER III

3.1 Methodology

The research setting is the non-traditional export sector of the Ghanaian economy.

The identification of the specific products for research was based on GEPCs list of

prioritized NTEs using 2006 as the base year. Two indices were employed for

analysis: The Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) and the Lafay Index (LI).

The merits informing the choice of these indices are discussed subsequently. The aim

of the research method is to answer the following research question: are the listed

products competitive? The underlying reasons resulting from the answers to this

question are subsequently discussed in following sections.

3.2 Comparative Advantage

Numerous systems have been devised to measure the patterns of trade, including

export competitiveness. The concept of comparative advantage is widely used in

economic literature to evaluate the patterns of trade and specialization of countries in

commodities which they have a competitive edge (Prasad, R. 2006). The paper

employs the so-called Balassa index with some modifications to measure Ghanas

competitiveness in the identified top-ten NTEs. The Balassa index, the Revealed

Comparative Advantage (RCA)

9

of country i in the trade of a product j is measured

by the items share in the countrys exports relative to it share in the world trade.

(Leishman et al 1999). It is calculated as follows:

i

ij

S

S

RCAij =

where

=

i

ij

X

ij

X

ij

S

9

The RCA has the disadvantage of obscuring real comparative advantages or disadvantages

in products groups where trade is distorted by export incentives and trade barriers primarily

agricultural products. These distortions results in upwards biased RCA index values (Prasad

2006; ITC 2001). The Paper employs Laursen (1998) adjustment technique to the RCA to

make it more symmetric.

21

( is the ratio between country is export of good j (denoted as X

ij

) and the world

export of good j;

=

j i

ij

j

ij i

X X S

,

is the ratio between country is total exports and the total exports of the entire world.

By definition therefore, the market j becomes the focal point of comparison of

country is export of product j relative to the total world exports. In our case S

ij

is the

ratio between Ghanas export of a selected NTE and the world export of that product

and S

i

is the ratio between Ghana total exports and the total exports of the world.

RCA

ij

greater than 1, indicates that country is share in market j is greater than its

share in the world market, implying that the country is relatively morecompetitive in

market j than in other markets and hence has a revealed comparativeadvantage in

good j. The opposite is true for RCAij less than 1. The RCA however, produces

outputs incomparable at both sides of 1. Laursen (1998) employs the following

mathematical equation to make the resulting RCAs symmetric: (RCA-1)/(RCA+1).

The resulting measure which ranges from -1 to +1 is referred to as the Revealed

Symmetric Comparative Advantage (RSCA). Non- adjusted Balassa Index runs the

inherent risk of overestimating index above 1 when compared to observations below

1. The RSCA normalises this shortcoming of the RCA. The main short-coming of RCA,

a single flow indicator, is that it does not allow a synthetic assessment of thecountry's

position in international trade (Iapadre, 1996). For any given level of export

specialization, as measured by the RCA or the RSCA indicator, a country's

comparative advantages may differ, according to its degree of import dependence.

Therefore, other indicators that bring import into the equation become imperative.

3.3 Lafay Index

The second method employs the Contribution to the Trade Balance (CTB), an

indicator developed by the French Economic Research Institute CEPII. Also referred

to as the Lafay Index (Dagenais and Muet 1994) it compares the balance of trade of a

country for a selected product to a theoretical balance, corresponding to the absence

of specialization (ITC 2006; Zaghini, 2003). This instrument is useful in identifying

22

strong and weak points of a specific country and comparing them with its

competitors at an aggregated level of industry. Unlike the RCA, the Lafay Index

takes into account, both a countrys exports and import of the focal product

considering the important role of intra-industry trade worldwide (Zaghini, 2003).

Secondly, Zaghini, again, asserts the normalization of each products trade balance

over their respective overall trade balance eliminates structural distortion introduced

by short term cyclical fluctuations which have significant influence in the magnitude

of trade flows. The Lafay index is given for a country i and good j as:

( )

( ) ( )

= =

=

+

+

(

(

(

(

=

N

j

i

j

i

j

i

j

i

j

N

j

i

j

i

j

N

j

i

j

i

j

i

j

i

j

i

j

i

j i

j

m x

m x

m x

m x

m x

m x

LFI

1 1

1

100

where xi j and mij are exports and imports of product j of country i, towards and

fromthe rest of the world, respectively, and N is the number of items. According to

the index, the comparative advantage of country i in the production of item j is thus

measured by the deviation of product j normalised trade balance from the overall

normalised trade balance, multiplied by the share of trade (imports plus exports) of

product j on total trade (Zaghini, 2003). It therefore holds true that

0

1

=

=

N

j

i

j

LFI

.

Positive values of the index indicate a degree of comparative advantage whilst

negative value is an indication of the erosion of specialization. According to Iapadre

(1996), besides being used as a measure of trade performance, in disaggregated

analysis, the normalized trade balance such as the Lafay index, is often interpreted

also as an indicator of trade specialization. High and positive normalized balances are

recorded for commodities in which the national production is very competitive in

both foreign and domestic markets. Therefore, it may be considered as an ex-post

synthetic indicator of the competitive success of national products.

23

3.4 Data Requirements and Sources

The empirical analysis is conducted using trade data from the International Trade

Centres (ITC), interactive trade databases (TRADEMAP, PRODUCTMAP AND

MACMAP). The database provides comprehensive trade data including tariffs,

performances on existing and new market opportunities.

It reports for over 220 countries and territories covering approximately 5300 products

defined at the 2, 4, or 6 digit level of the Harmonized System of trade classification.

Trade statistics between 2001 and 2006 are analyzed. A particular short-coming of

the ITC data is that it occasionally mirrors corresponding figures from partner

countries, as proxies, of non-reporting focal countries (mainly from developing and

least-developed countries) (ITC, 2006).

24

4CHAPTER IV

4.1 RESULTS

4.1.1 Disaggregation of Ghanas Exports

Table 6 shows the merchandise exports of Ghana ending 2006. Ghanas total

export reached US$3.6 billion in 2006. Cocoa and product remain the

countries number export followed by precious metals and wood products.

Total merchandise export between 2005 and 2006 declined by 35 per cent

resulting in relative poor export performance of its major exports including

cocoa, wood products and edible fruits. The export of footwear increased

significantly by as much as 209410 per cent between 2005 and 2006 whilst

meat, fish and seafood recorded the highest losses within the same period.

Table 5: Major products exported by Ghana (2006)

RANK

PRODUCT VALUE EXPORTED

currency

GROWTH RATE (EXPORTED

VALUE) currency

SHARE IN WORLD

EXPORTS in %

2002-2006 2005-2006

All 3,613,994 28 -35 0.03

1 Cocoa/Cocoa

Products

1,241,079 14 3 5.34

2 Precious metals 1,153,148 31 28 0.49

3 Wood products 280,727 35 -61 0.25

4 Cotton 229,421 38 6573 0.46

5 Plastic products 175,526 85 1099 0.05

6 Edible fruit 143,747 76 -59 0.27

7 Footwear 43,997 291 209410 0.06

8 Aluminium

product

43,856 63 -7 0.03

9 Meat, Fish and

seafood

35,248 -14 -90 0.12

10 Oilseed, grain,

seed

32,527 26 -16 0.1

Source: International Trade Centre (ITC, 2006) with own modifications.

25

4.1.2 Approximation of Competitiveness: The Symmetric Revealed

Comparative Advantage (SRCA)

Table 6 illustrates the level of specialisation of the selected NTEs from Ghana by

comparing the countrys export structure of each product to the world export

structure of the rest of the world. When the RSCA for a given product (and for a

given country) equals -1, that sector is structurally under-specialized compared to the

rest of the world and conversely, a sectors comparative advantage is revealed at +1.

From the RSCA figures (2003 - 2006), products that revealed relative strengths

include cocoa paste, cocoa butter, veneer sheets, plywood, cashew and fresh

pineapples. Preserved fruits revealed relative advantages in 2003 and 2004 but

subsequently declined in 2005 before strengthening the following year. Tuna enjoyed

a brief spell in 2003 but have since declined considerably. These figures in

themselves do not assume that the sectors have not been improving. Corresponding

increases in world exports impact negatively on RSCA even if absolute imports from

Ghana in a particular sector increases.

Table 6: Revealed Symmetric Comparative Advantage (RSCA).

4.2 Normalized Competitiveness Measure: The Lafay Index

From the tabulated Lafay index for Ghana in 2006 (Table 7), cocoa paste had the

highest score (12.5) followed by plywood (8.0) and Cocoa butter (7.5). Conversely,

Prepared tuna was the worst performing product (-38.2) with frozen tuna following

PRODUCT 2003 2004 2005 2006

Cashew Nuts 0,96 0,98 1,00 0,97

Shea Nuts 1,00 - - -

Fresh Pineapple 1,00 1,00 0,97 0,99

Preserved Fruits 0,79 0,83 0,24 0,61

Frozen Tuna 0,87 -1,00 -0,36 -0,78

Prepared Tuna 0,48 0,92 0,74 0,87

Cocoa Paste 1,00 1,00 0,99 1,00

Cocoa Butter 0,91 0,99 0,98 0,99

Veneer Sheets 0,99 0,99 0,98 0,99

Plywood 0,94 0,94 0,99 0,97

26

closely (0.0005). Generally, the RSCA compares well with the Lafay Index for the

year under review and for each product. However, a close look at pineapple exports

revealed a strong index with the RSCA but relatively subdued by Lafay. This is

because unlike RCA (RSCA) which does not take imports into account, Lafay index

also normalises the trade balance for each product. Relatively high degree of

importation of prepared tuna for example could explain why a strong RCA index in

2006 is not reflected in the Lafay Index.

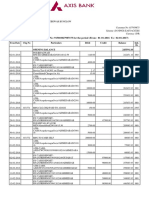

Table 7: Lafay Index of Ghanaian Top-performing NTEs (2006)

PRODUCT LAFAY INDEX, 2006 PRODUCT LAFAY INDEX,

2006

Cashew Nuts 1.255781 Cocoa Paste 12.47717

Shea Nuts - Cocoa Butter 7.496998

Fresh

Pineapple

1.812341 Veneer Sheets 6.918528

Preserved

Fruits

0.195966 Prepared Tuna -38.1971

Frozen Tuna 0.000521 Plywood 8.039844

The second stage compares Ghanas Lafay Index to that of selected competing

countries

10

. Table 8 provides and overview of the Lafay indices of these competing

exporters of Ghanas main exporting NTEs in 2006

11

. Ghana compares relatively

well in the production and exports of unshelled cashew, cocoa products, veneer sheet

10

The selection of the competing countries were based on the following measures:

competitive countries that share geographical relationship with Ghana and by extension have

common production patterns for example Cote dIvoire; secondly, countries that enjoy

similar tariff measures as Ghana on the EU market example Fiji (via the Cotonou

Agreement); Finally, world top performing countries for the selected product in the absence

of conditions 1 and 2.

11

The calculation of the competing countries Lafay indices was based on the assumption

that for each selected NTE, that country exports and imports the remaining NTEs in equal

value as Ghana. Holding the value of imports and exports of the remaining NTEs was

important to establishing a basis for comparison.

27

and plywood. It however, performs comparatively poorly in the exports of tuna

products, as well as, unshelled cashew and preserved fruits. Essentially the bulk of

Ghanas cashew exports are sold unshelled (1.25) like her competing African

countries of Cote dIvoire (12.87) and Guinea-Bissau (6.97). The competitiveness

indices of India and Vietnam in the exports of shelled cashew reflects it performance

in 2006. The negative values of Belgium and the Netherlands in the exports of

pineapple and cocoa paste is indicative of the fact that these countries are mainly into

re-exports of these products rather than primary producers. For example, in 2006

Belgium imported US$ 691 Million in value of raw cocoa of which approximately 66

per cent came from Ghana and Cote dIvoire. Kenya is the most competitive exporter

of preserved fruits from Africa exporting over US$ 50 Million worth in 2006

compared to Ghanas exports of US$ 1.8 Million. Ghana has the best plywood

industry in Africa even though China, Malaysia and Brazil have significant share of

that product export market in the world. China, like Malaysia, supplies primarily the

United States of America, South Korea, J apan and the EU whilst over 88 per cent of

Ghanas plywood is supplied to Nigeria (ITC, 2006). In the cocoa industry, Cote

dIvoire has consistently proven the main competing supplier other than Ghana albeit

both countries have a competitive market share on the international cocoa market.

Ghana compares relatively well in the production and exports of unshelled cashew,

Cocoa products, Veneer sheet and Plywood. It however, performs comparatively

poorly in the exports of tuna products, as well as, unshelled cashew and preserved

fruits. Essentially the bulk of Ghanas cashew exports are sold unshelled (1.25) like

her competing African countries of Cote dIvoire (12.87) and Guinea-Bissau (6.97).

The competitiveness indices of India and Vietnam in the exports of shelled cashew

reflects it performance in 2006. The negative values of Belgium and the Netherlands

in the exports of pineapple and cocoa paste is indicative of the fact that these

countries are mainly into re-exports of these products rather than primary producers.

For example, in 2006 Belgium imported US$ 691 Million in value of raw cocoa of

which approximately 66 per cent came from Ghana and Cote dIvoire. Kenya is the

most competitive exporter of preserved fruits from Africa exporting over US$ 50

Million worth in 2006 compared to Ghanas exports of US$ 1.8 Million. Ghana has

the best plywood industry in Africa even though China, Malaysia and Brazil have

28

significant share of that product export market in the world. China, like Malaysia,

supplies primarily the United States of America, South Korea, J apan and the EU

whilst over 88 per cent of Ghanas plywood is supplied to Nigeria (ITC, 2006). In the

cocoa industry, Cote dIvoire has consistently proven the main competing supplier

other than Ghana albeit both countries have a competitive market share on the

international cocoa market.

Table 8: Lafay Index of Major Competitors of NTEs exported by Ghana (2006).

CASHEW (SHELLED) LAFAY INDEX

India 76,80

Vietnam 52,10

Ghana 0

Cashew (Unshelled)

Cote D'Ivoire 12,87

Guinea-Bissau 6,97

Ghana 1.25

Pineapple

Costa Rica 61,24

Belgium -42,22

Cote D'Ivoire 9,97

Ghana 1.81

Preserved Fruits

China 142,95

Thailand 77,49

Kenya 7,24

Ghana 0.19

Tuna

Spain 6,65

Indonesia 8,13

Fiji 0,89

Ghana 0.0005

Cocoa Paste

Netherlands -3,76

Cote D'Ivoire 33,16

Ghana 12.47

Cocoa Butter

Netherlands 41,98

Malaysia 49,78

Cote D'Ivoire 25,45

Ghana 7.49

Veneer Sheet

USA 73,78

Gabon 16,55

Cote D'Ivoire 8,51

Ghana 6.91

29

Plywood Lafay Index

China 410,22

Malaysia 272,95

Brazil 91,69

Ghana 8.04

30

5CHAPTER V

5.1 Discussion of Results

The factors discussed in section two which are believed to affect the competitiveness

and performance of NTEs will be employed to discuss the findings of the research.

These include standards, prior experience in exports, diversification, government

interventions, barriers (discussed under porter), existence of intra-industry trade etc.

The resulting indices are not exhaustive in defining the competitiveness of the NTEs.

However, they shed important insight into some aspects of the structure, character

and direction some of which are discussed below in sector-by-sector basis.

5.1.1 Cocoa Industry

The cocoa and timber industries have long been the backbone of the Ghanaian

economy and have undergone significant structural and institutional transformation

since independence (WTO, 2008). The export of raw products used to characterize

the two sectors and even today substantial portions of cocoa and timber are exported

in the raw state (see Table 5). Vertical diversification of cocoa beans into power,

paste and butter was largely informed by the continued deterioration in the world

markets prices of cocoa beans beginning in the late 1970s (Dand, 1999). Cocoa and

timber have high RCA and Lafay indices indicating party the existence of

comparative advantage but also could as a results of lessons learnt from past export

performance in those industries (see Chapter 2.5.1). Cocoa is Ghanas most dominant

cash crop and single most important export product (WTO, 2008; ITC, 2006) and the

importance of that industry to Ghanaian economy is underscored in its precise

network of administration under the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning

(MOFEP). The COCOBOD, a semi-autonomous institution under MOFEP is the

main body tasked with research and marketing of cocoa in Ghana.

The COCOBOD carries out its research work through the Cocoa Research Institute

of Ghana (CRIG) which provides research and advice on, amongst others, agronomic

practices that impact on diseases and pests. The Ministry of Food and Agriculture

provides Extension Services to farmers. The Cocoa Marketing Commission, CMC is

the body responsible for marketing of cocoa beans either through exports or sale to

31

local processing companies. CMC purchases cocoa beans from farmers through

Licensed Buying Companies (LBCs) which are mainly private entities involved in

internal marketing of the beans. Price of cocoa beans purchased from farmers is

decided by the Producer Price Review Committee (PPRC) which has farmer, as well

as, government representation.

Domestic processing of cocoa is growing in importance with a medium-term

objective of 40% output. As of 2007, 5 private processing companies were involved

in the production of butter, powder, liquor and cocoa by-products with a combined

processing capacity of 253, 000 MT (WTO, 2008). The GCPC is however, the main

cocoa processing industry, and is partially government-owned. Since locally

produced cocoa products compete directly with processing companies on the export

market, tariff escalation on these markets is the main draw on domestic processing

for exports.

Table 9: World Imports of Cocoa and Cocoa Products (2002-2006).

Cocoa Product Combined

World Imports

Unit Value

(US$/MT)

Growth in

Import Value

2002-2006

Growth in

Import

Quantity

2002-2006

1 Chocolate 13,491,880 3,334 14 7

2 Beans 4,874,867 1,655 6 11

3 Butter/fat &Oil 2,794,413 4,140 18 6

4 Paste 1,202,692 2,098 3 7

5 Powder 918,066 1,547 -2 5

6 Husk/Skin/Waste 43,143 432 10 -2

Source: ITC, 2006.

According to the WTO (2008), Ghana imposes a 20% import tariff on cocoa and

cocoa products. Cocoa exports are subject to taxes and repatriation of export revenue

and its conversion into local currency. The industry is unmatched in the level of