Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Student Perceptions of A Positive Climate For Learning: A Case Study"

Încărcat de

Tan Soon YinTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Student Perceptions of A Positive Climate For Learning: A Case Study"

Încărcat de

Tan Soon YinDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Educational Psychology in Practice Vol. 27, No.

1, March 2011, 6582

Student perceptions of a positive climate for learning: a case study

Alexia Gillen*, Angela Wright and Lucy Spink

School of Education, Communication and Language Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK

Educational 10.1080/02667363.2011.549355 CEPP_A_549355.sgm 0266-7363 Original Taylor 2011 0 1 27 alexia.gillen@ncl.ac.uk AlexiaGillen 000002011 & and Article Francis (print)/1469-5839 Francis Psychology in Practice (online)

This study examines students perceptions of factors they consider important in creating a positive classroom climate for learning. It investigates preferred learning environments and explores the associated elements identified by students. Four initial focus groups were employed with an inductive thematic analysis being undertaken to identify themes from these discussions. Based upon the results, a questionnaire was constructed and administered to 116 students in Year 7 and Year 8. Thematic analysis of focus group transcripts identified 11 themes pupils perceive as important in creating a positive learning climate. These themes reflect five dimensions of classroom climate (physical aspects, order and organisation, lesson content and delivery, peer relationships and staff/student relationships). Questionnaire analysis using a t-test demonstrated that these factors were considered to be important by Year 7 and 8 students as a whole, with no significant gender differences. Implications for practice in creating a positive climate for learning are identified and questions for future research are raised. Keywords: students; perceptions; classroom climate; learning environments

Introduction Defining school and classroom climates While a single agreed definition does not exist, classroom climate has been described as the perceived quality of the classroom setting and is seen as a major determinant of behaviour and learning (Adelman & Taylor, 1997). Byrne, Hattie and Fraser (1986) suggest that the ideal classroom climate is one that is conducive to maximum learning and achievement (p. 10). The term school climate has been defined as the way in which students experience psychological and physical characteristics of the school environment as a whole (Sink, 2005) and has been associated with key outcomes such as academic achievement (Reid, Gonzalez, Nordness, Trout, & Epstein, 2004) and school leaving age (Reinke & Herman, 2002). The climates of the classroom and school have been described as a reflection of the values, belief systems, ideologies and traditions within a school setting, thereby reflecting the schools culture (Adelman & Taylor, 1997). Although the terms school climate and classroom climate are often used interchangeably throughout the literature, they do have distinct definitions. Johnson and Johnson (1999) suggest that the school climate relates to the organisational setting for learning and teaching and can be associated with the accumulation of classroom

*Corresponding author. Email: alexia.gillen@ncl.ac.uk

ISSN 0266-7363 print/ISSN 1469-5839 online 2011 Association of Educational Psychologists DOI: 10.1080/02667363.2011.549355 http://www.informaworld.com

66

A. Gillen et al.

climates. Therefore, it is evident that a complex interaction occurs between school and classroom climates, with each environment influencing the other. For the purpose of this study, the focus is upon the classroom climate, which the authors regard as the way in which students experience the psychological and physical characteristics of the classroom. Johnson and Johnson (1999) suggest that by focusing on the creation of positive classroom climates that provide a supportive environment for students to learn, a beneficial and supportive school climate can be encouraged. Discussion throughout this paper explores elements of the classroom environment considered to support learning.

Impact of classroom climate The climate within a classroom can impact upon students within the setting in a number of ways. Miller, Ferguson, and Byrne (2000) investigated the influence of classroom climate in relation to difficult classroom behaviour and found that students perceived factors such as strictness of classroom regime and fairness of teachers actions as influential on behaviour. The literature (Anderson, Hamilton, & Hattie, 2004; Glover & Law, 2004; Ryan & Patrick, 2001) identifies links between the climate of the classroom and the factors that impact on learning such as student engagement, attendance, self-efficacy and the overall quality of school life (Fraser, 1998). This highlights how the climate within an environment can influence the degree to which students are willing and able to learn, and the extent to which the environment supports them in this task. Whilst Freiberg (1998) agrees that the school climate can be a positive influence on well-being, he also notes its potential to be a significant barrier to learning, impacting adversely upon academic performance and pupil motivation.

A multi-dimensional environment Climates within a school can be considered as multi-dimensional (Marshall, 2004) and due to the complex interactions of social, physical and organisational factors: the classroom climate has been described as a fluid state (Adelman & Taylor, 1997). Bronfenbrenners Eco-systemic Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) provides a model to explain the complex interactions that occur between individual students and their environment, contributing to the classroom climate and learning outcomes. Stemming from a social constructionist perspective, an eco-systemic approach suggests that a dynamic, interactive process takes place whereby the young persons characteristics, values and responses interact with factors within their environment, influencing both the individual and the eco-system surrounding him or her (Kelly, 2008). This approach also highlights the need to acknowledge the way in which school climate may be influenced by systems that are both internal and external to the organisation.

Identifying dimensions within a classroom climate Based on an extensive review of the literature, Trickett and Moos (1973) identified three sets of variables that influenced the climate within a classroom:

Educational Psychology in Practice

67

relationships (including teacher support, the interactions between students and their peers and teachers); systems maintenance and change (such as organisation and order, rule clarity and teacher control); goal-orientation (including task-orientation and competition).

From these, the Classroom Environment Scale (CES; Trickett and Moos, 1973) (a 90 item questionnaire) was devised and has become widely utilised as a measure of classroom climate. However, the measure was developed in the United States and one therefore should be mindful if generalising to different countries and cultures. Nevertheless, the research conducted by Trickett and Moos (1973) was significant in that it provided a framework for factors thought to impact upon the classroom climate for learning and established a gateway for future research. Social elements Further research by Trickett and Moos (1974) highlighted the importance of affiliation in the classroom, illustrating how levels of friendship between students provided additional learning support, such as helping each other with homework and enjoying working together. However, although the importance of friendship has been shown to be relevant during adolescence (Adams, Gullotta, & Markstrom-Adams, 1994) the impact may vary with the age of the student. Ryan and Patrick (2001) added further weight to the importance of social factors. Their research found that students engage in more adaptive patterns of learning in a classroom where they are encouraged to work with others, their ideas are respected and teachers are understanding and supportive of needs. Although perceptions measured in the Ryan and Patrick (2001) study were specific to maths classes, research by Anderson et al. (2004) also found that social aspects of classroom climate generally are significantly related to student participation, engagement and task completion, all of which are measures of motivation to learn. Furthermore, Topping (2005) proposed that thoughtful use of cooperative learning can encourage academic gains in a range of targeted curriculum areas. Describing classrooms as inherently social places, Ryan and Patrick (2001, p. 438) also found that students perceptions of teacher support and the teacher promoting interaction and mutual respect were related to positive changes in motivation and engagement, impacting upon the climate for learning. Ryan, Gheen and Midgley (1998) found students sought more help in classrooms where teachers attended to students academic and social needs, illustrating the significant impact the teacher can have in creating a positive learning and social climate. Physical elements While the majority of research (discussed earlier) has focused upon the impact of social elements of the learning climate, physical factors have also been explored. Features such as air quality (Khattar, Shirey, & Raustad, 2003) condition of furniture (Knight & Noyes, 1999) and displays (Killeen, Evans, & Danko, 2003) are all considered to influence student engagement, yet results from research into these aspects are often equivocal (see Woolner, Hall, Higgins, McCaughey, and Wall [2007] for review of the impact of physical aspects on students ability to learn).

68

A. Gillen et al.

Creating a positive classroom climate for learning Research discussed earlier has considered the way in which different factors can impact upon the climate in both the classroom and school. With inclusion being a current driving force in education and psychology, there is a need for schools to develop a positive and supportive climate that responds to the diverse needs of all. As emphasised in Index for Inclusion (Booth & Ainscow, 2002), to become inclusive, schools need to reduce barriers to learning by restructuring cultures, policies and practices to make changes for the benefit of all students. A major theme to emerge from schools that have been successful in creating a more inclusive atmosphere is the emphasis placed on developing more positive relationships between staff and pupils, and valuing the opinions of the student body (Osler, 2000). These findings were supported by Marshall (2004), who identified additional factors that are influential to school climate (and, by inference, classroom climate) such as feelings of trust and respect for students and teachers. Hughes and Vass (2001) suggest that teachers can implement a range of strategies that will have a positive impact on the climate of the classroom. Published in the Department for Education and Skills (DfES, 2004) guidelines, the strategies highlight the importance of considering social, organisational and physical aspects and the impact they have on students ability to learn. These strategies will be explored further in the discussion. Researching the student perspective While research cited has illustrated factors that impact upon the climate for learning, Flutter (2006) suggests that students perception of the environment can be equally if not more influential than other factors deemed to be significant:

For students, the physical conditions of school are often the familiar face of a much deeper set of issues about respect feeling that you matter in school, that you belong, that it is your school and that you have something to contribute. (p. 191)

Dorman (2008) notes that, while much research explores classroom climate in the United States and Australia, few European studies have been published. LaRocque (2008) proposes that examining the classroom environment from the perspective of the students appears to be most promising for understanding the educational process. Moreover, educational research is becoming increasingly focused on the student voice, enabling researchers to gain a better understanding of the factors that impact on a students experience within school (Flutter & Rudduck, 2004). The increasing focus on the importance of students views and perceptions of their preferred learning environment (Dorman, 2008; Sanorr, 2001) and the impact this may have on affective and cognitive outcomes (Fraser, 1998) highlights the need for further consideration in this area. Current study Following Ofsted inspection which highlighted weaknesses in the general areas of teaching and learning, the current research was conducted at the request of the school leadership team. The research aimed to explore aspects of the classroom environment that students perceive as important in creating a positive climate for learning. Freiberg

Educational Psychology in Practice

69

(1998) suggests that the climate for learning may be particularly important for students in their initial years at an establishment in order to support a smooth transition between schools. In light of this, the researchers agreed to involve pupils in Years 7 and 8 who had most recently experienced transition into the secondary school setting. The research sought to identify the degree of importance that students attach to different elements and provide a clear picture of the way in which features of the classroom environment can be adapted to support student learning. Method Background to the school The Year 7 and Year 8 pupils who participated in this study attend a Middle School in the UK. The proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals is higher than average and some pupils experience social and economic disadvantage. Students come from a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds, with significant pockets of deprivation. The proportion of pupils with learning difficulties and disabilities is similar to other schools but the number with statements of educational needs is higher. The Year 5 to Year 8 Middle School is federated with a High School and shares a governing body. More recently, the Middle School has been co-located with the High School. Years 7 and 8 pupils are educated within the High School and Years 5 and 6 in a separate 113 pupil primary unit. Overview of procedures The study applied a mixed-methods approach to obtain quantitative and qualitative data and to offset different categories of bias and measurement error (Zhang, 2008). Data triangulation was used to increase the validity of the qualitative research (Zhang, 2008). Initially, focus groups were conducted to gather the views of a sample of students about their perceptions of what creates a positive learning climate. This approach is supported by Barbour (2007) and was chosen so that open-ended questioning would determine variables that could later be studied quantitatively (McCracken, 1988). Inductive thematic analysis (as described by Braun and Clarke [2006]) was performed on the qualitative information gained to identify dimensions and themes important to the students. These dimensions and themes were used to create a questionnaire that was completed by all Year 7 and Year 8 students to provide quantitative data.

Focus groups Participants The population consisted of 61 Year 8 pupils and 55 Year 7 pupils; with 68 being male and 48 female. A sample of four boys and four girls from each year group was selected to participate in the focus groups. Focus groups were divided by gender and year group to encourage a more open forum for discussion. Participants were randomly sampled from an alphabetical year group list. Although only four pupils were required to participate in each focus group, five names were chosen in case of absence on the scheduled date of the group. The sampling fraction was computed by dividing the size of the sample needed (five girls and five

70

A. Gillen et al.

boys) into the total number of girls and boys in each year group (for example, in Year 8 the total number of boys was 40 so this was divided by five, the number of participants needed for the focus groups, and as a result, every eighth person on the list was selected as a participant). The beginning of the list was selected as the starting point and every eighth number was the person selected. Materials Focus groups were recorded using a dictaphone and were later transcribed by one of the researchers. Additional ideas from the pupils were recorded using large sheets of paper and marker pens. Transcriptions were analysed using thematic analysis to draw out salient themes. Procedure Each focus group was asked by a member of school staff to meet with all three researchers. Focus groups commenced with introductions, an explanation of the aims of the group and the research. Participants were requested to work collaboratively to think about what their ideal classroom (that helped them to learn best) would look like and include. Pens and paper were provided. Pupils were directed to either draw or use words to describe their ideal classroom. Pupils were encouraged to expand on these initial ideas to inform the main discussion in the focus group. The focus groups lasted between 40 minutes and one hour. All participants were made fully aware of the purpose of the focus groups and were told from the outset that participation was optional and they could choose to leave at any time.

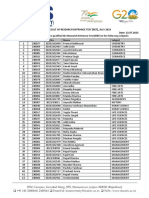

Analysis Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). To increase inter-rater reliability, each researcher analysed the transcriptions separately and compared interpretations to reach agreement on themes identified. A total of 11 themes was identified. Due to commonalities in themes, these were grouped into five over-arching dimensions; for example, seating arrangements, displays on walls and quality of environment were grouped into the dimension Physical Environment. Some themes were reflected in more than one dimension (see Figure 1 for dimensions and component themes).

Figure 1. The five overarching dimensions and component themes.

Questionnaire Construction The questionnaire was constructed using the information from the thematic analysis. The questionnaire consisted of 33 statements; three statements were devised to represent varying aspects of each of the 11 themes (see Appendix 1). Where possible these were adapted from the CES (Trickett & Moos, 1973). The CES was selected due to a number of factors: previous wide-spread use in this area (Fisher & Fraser, 1983a, 1983b); appropriateness for secondary age pupils (Moos, 1979; Fisher & Fraser, 1983b); and ease of adaptability. Of the three statements for each theme, two statements were worded positively (for example, It would help me to learn best if the

Educational Psychology in Practice

71

Figure 1.

The five overarching dimensions and component themes.

tables were arranged in groups instead of rows) and one statement worded negatively (for example, I would learn best if I didnt know what the lesson objective was) or was the reverse of a previous statement (for example, It would help me to learn best if I could choose who to sit with and I would learn best if the teacher told me who to work with) so as to minimise respondent acquiescence and encourage careful consideration of statement responses (Coolican, 2004). Statements were randomly ordered as recommended by Robson (2002). One of the themes emerging from the focus groups, Teacher Attributes, was omitted from the questionnaire because it was felt this is an aspect of the learning environment that cannot be easily controlled. Participants were required to answer each statement on the questionnaire using a fourpoint Likert-type scale. The researchers acknowledge criticism that a four-point scale may result in bias through the issue of forced choice for those students who may genuinely be undecided on an issue; however it was agreed that results could offer greater insight into student views if response acquiescence was reduced by eliminating the mid-point of the scale. The use of a four-point scale is already evident in empirical research on attitudes, for example, Godfrey, Partington, Richer, and Harslett (2001) and was, therefore, considered valid. To increase understanding of the points on the scale the following verbally meaningful descriptors were assigned: Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, and Strongly Disagree (Leong & Austin, 2006). Questionnaire pilot The questionnaire was piloted with four pupils who had previously participated in the focus groups, in order to eradicate any difficulties regarding wording and administration. The pupils involved were randomly chosen by the Assistant Head Teacher. Any comments were acknowledged and necessary changes made.

72

A. Gillen et al.

Participants All Year 7 and Year 8 pupils present on the day of administration completed the questionnaire. School policy enabled the completion of anonymous questionnaires by pupils without additional parental consent. Administration Registration period was identified by the Assistant Head Teacher as the most appropriate time for questionnaire administration; therefore school staff administered them. To ensure consistency, specific and detailed instructions were provided for staff prior to administration. Participants were encouraged to complete the questionnaire independently but support was given if required. All participants were informed of their right to anonymity and confidentiality. They were advised that participation was optional. Analysis Of the 124 returned questionnaires, eight were not included for analysis due to incorrect completion, that is, a response was not provided for all statements or multiple responses were selected for one statement. The remaining questionnaires were subjected to analysis using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (see Appendix 2 for question coding). Chi-square and t-test analysis were performed to investigate statistical significance in relation to year group and gender ratings on all themes and dimensions. Results Questionnaire responses were totalled and the mean score for each question calculated. Conversion of scores into means allows a more accurate representation of the continuous nature of attitude or strength of opinion. The use of meaningful descriptors on a spectrum from strongly agree to strongly disagree further supports this type of analysis. This approach is consistent with that taken in a number of other studies of classroom climate (see Anderson et al., 2004; Byrne et al., 1986). Chi-square tests The data for each question were visually scanned and questions that showed large amounts of variance in responses were subjected to chi-square analysis. This form of analysis is useful for testing if observed data are representative of particular distributions. This is based on a comparison of observed and expected counts and was used to compare statement responses between genders: male and female, and between year groups. Despite the fact that a significant difference was revealed for a number of statements, these results were invalid because more than 20% of the cells had a count less than five. However, one valid significant difference (p < 0.05) was identified for gender in response to the statement I would learn best if the teacher ALWAYS used the same task at the start of the lesson, with boys showing more agreement than girls. Levels of significant agreement and disagreement Due to the non-significant chi-square results, responses were analysed to identify statements showing a high level (90% or more) of agreement or disagreement. Percentage

Educational Psychology in Practice

Table 1. Statement It would help me to learn best if the tables were arranged in groups instead of rows I would learn best if I was comfortable in the classroom I would learn best if the teacher listened to my views It would help me to learn best if I could choose who to sit with I would learn best if I knew that I was doing well I would learn best if the same rules were used for everyone I would learn best if I could share ideas with my friends I would learn best if the activity was explained clearly Statements showing agreement of 90% or more. Theme Seating arrangements

73

Quality of environment Pupil voice Seating arrangements Reward Consistency of approach Collaborative working Clarity of instructions and expectations I would learn best if the teacher offered help to me when I am stuck Teacher support I would learn best if I could do practical activities e.g. drama, Range of activities making things I would learn best if I felt comfortable asking the teacher for help Teacher support I would learn best if the classroom was tidy and well-organised Quality of environment Table 2. Statement I would learn best if the classroom was NOT colourful Statement showing disagreement of 90% or more. Theme Quality of environment

of agreement was calculated by combining responses of Strongly Agree and Agree, and disagreement was calculated by combining the categories of Strongly Disagree and Disagree. Twelve statements showed agreement of 90% or more (see Table 1). Only one statement showed disagreement of 90% or more (see Table 2). t-Tests Results showed that there were no significant differences between either year group or gender ratings on any theme or dimension, except for one gender response as previously mentioned. Comparison of themes To enable the strength of agreement on the importance of each theme to be determined, the means of the three statements representing each theme were added together to calculate totals for themes. The maximum total for each theme is 12 (three statements multiplied by maximum value of four). The themes were then ranked to highlight the perceived order of importance of each element in contributing to the creation of a positive climate for learning (see Table 3). Within these 11 themes Lesson Structure was perceived to be least important and Quality of the Environment the most important. Comparison of overall dimensions As the five overarching dimensions were constructed from varying numbers of themes, scores were converted to proportions of their maximum. For each

74

A. Gillen et al.

Ranking of themes by mean score. Theme Quality of environment Reward Teacher support Displays Clarity of instructions and expectations Seating arrangements Collaborative working Range of activities Pupil voice Consistency of approach Lesson structure Mean total 10.11 9.85 9.63 9.47 9.43 9.40 9.36 9.35 9.22 9.02 8.68

Table 3.

Rank importance #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6 #7 #8 #9 # 10 # 11

Table 4.

Ranking of dimensions by mean score. Dimension Physical environment Order Peer Lesson Staff Mean score (maximum score = 1) 0.81 0.79 0.78 0.77 0.76

Rank importance #1 #2 #3 #4 #5

dimension, the achieved scores for each theme were added together and then divided by the maximum possible score for that dimension, for example, the dimension of Physical Environment = Quality of environment + Displays + Seating arrangements 36 (that is, nine questionnaire statements maximum rating value of four). This proportional score, therefore, represents the strength of agreement for a dimension and its perceived importance in creating a positive climate for learning (see Table 4). This highlights the dimension of Physical Environment to have greatest perceived importance and Staff/Student Relationships as being the least important. Discussion This case study indicates that students do perceive particular elements to be important through the creation of a positive climate in supporting their learning, and the multiplicity of dimensions identified is consistent with Marshall (2004). The findings of the perceived importance of physical elements of the classroom environment is consistent with Woolner et al. (2007) and the importance of social elements with Ryan and Patrick (2001). Findings were consistent across both year group and gender, indicating shared perceptions. These results contrast with Byrne et al.s (1986) results which concluded differences in students perceptions of preferred classroom learning environment do exist. However, the results may be of interest to educational psychologists (EPs) as a reminder that despite the recent emphasis placed on peer collaboration and

Educational Psychology in Practice

75

other social elements associated with learning, it should not be assumed these elements are as important to students themselves. Physical elements Whilst thematic analysis from the focus groups highlighted the importance of psychosocial aspects of the learning environment (for example, being able to work collaboratively and use peer support in learning), the overall results emphasise the perceived importance of the physical environment (for example, the layout and organisation of the classroom). This can be explained through basic needs psychology such as Maslows Hierarchy of Needs (Maslow, 1971) and highlights the importance of meeting basic needs, such as physical comfort, before an individual will consider their psychosocial needs. Social elements The most highly rated item on the questionnaire related to individuals choosing who they sit with, highlighting the perceived importance of social elements such as friendship and support. It should be noted that the attitudes teachers display towards the importance of promoting interaction and the development of mutual respect between peers will impact on student views of the importance of peer relationships within the classroom. Although staff/student relations were rated as the least important element, students still rated this as important in creating a positive learning climate. It is not possible within the design of the present study to measure the extent to which the relationships that students currently have with staff may have impacted on their preferences in this area. Order and organisation The importance of order within the classroom was consistently recognised, with the theme of reward rated most highly. The emphasis placed on the concept of reward may be a consequence of the disparity pupils experience in reward systems (for example free time, activity of own choosing) between primary and secondary classrooms. In the focus groups, students discussed systems such as Golden Time (time set aside, usually once a week, for children to engage in activities designed to provide time for relaxation and fun) in primary classes; this appears to have no place in secondary classrooms. By strongly rating a need for free time at the end of lessons, students drew attention to a need to reconsider the use of such practices beyond the primary classroom. This highlights the importance of staff in effecting this dimension within the classroom, that is, implementation of reward systems are largely determined by school policy and individual teacher practice. Consequently there is likely to be significant interaction between dimensions of order and staff/student relationships. This has considerable implications for the direct impact the teacher has in creating a positive classroom climate. Lesson structure and content The overall view emerging from the dimension of lesson structure and content is a need for clarity and variety. Students perceive that a range of activities, clearly explained and presented in a supportive environment, are important in creating a

76

A. Gillen et al.

positive climate to support learning. A need for more practical activities and learning in environments other than the classroom emphasises the importance of exploratory and participatory learning that is likely to have been evident in the primary curriculum that these students have recently experienced. Although the literature suggests (DfES, 2004) that a prompt start to lessons is desirable, students in this study showed indifference to this idea. This may be explained through their preference for time at the beginning of lessons to meet social needs with peers, or a possible need for a break from the constancy of the secondary timetable. The elements identified within this study as having importance for students may already be present in the actual learning environment experienced by participants. However this study emphasises factors that students perceive to have greatest impact on learning, possibly because they affect elements such as motivation and behaviour, concurrent with Ryan and Patrick (2001) and Miller et al. (2000). Although one cannot conclude that preferred learning environment is synonymous with the environment most conducive to learning, empirical evidence (Fraser, 1998) suggests that there are implications for affective factors and consequently cognitive outcomes and attainment from learning. Implications This study encourages recognition of the impact of the environment on individuals and emphasises the student voice regarding preferences for learning both key issues likely to be of interest to EPs. In engaging with schools, EPs are well placed to raise awareness and understanding of the immediate classroom environment. Supporting schools in understanding the association between the environment and affective factors such as motivation and well-being and the ultimate impact these factors have on attainment and learning of students has relevance to EP work. The findings have practical implications for schools and are congruent with DfES (2004) advice on improving learning climate. This study therefore supports the implementation of readily accessible strategies such as:

making the most of lesson beginnings greeting students, having activities and materials pre-prepared; sharing lesson objectives with pupils; allowing opportunities for collaborative working; using a range of seating arrangements for activities; providing displays of work; using language and opportunities to build relationships and raise self-esteem.

However, the results suggest there are additional factors to be considered:

The importance of the quality of the physical environment must not be underestimated. This includes the general comfort of students and the impact of learning in a tidy, well-organised environment. Students show a preference for selecting with whom they engage in collaborative learning activities. Simply providing opportunities for collaboration is insufficient, and students are likely to be more motivated to engage when they can choose who they work with. Students need to be involved in making choices about their learning, for example, curriculum content and approaches to learning.

Educational Psychology in Practice

77

Based on these considerations this study suggests a need for classroom practice to be developed and evaluated to better achieve a balance between independent and collaborative learning, as well as teacher controlled learning and student involvement in the learning process. This suggests a movement towards student centred environments, which emphasise collaborative learning may be required to meet learner preference. There are wider implications in considering how including pupil perceptions/voice in decision-making may not only improve aspects of pupil motivation and identity, but may also improve overall school culture and ethos, as indicated by Flutter (2006). EPs are well placed to support schools to recognise the benefits that may be gained through developing a stronger sense of community membership within the school as a whole and emphasising a pupil-centred approach to creating environments for learning, and facilitating changes at the psychosocial level to align the actual classroom climate with the expressed preferences of its pupils. Many exemplary teachers are likely to employ aspects of these factors in their practice and do create environments that are congruent with the preferences that students express. Factors identified in this study provide tools that may be used to evaluate the actual environments that exist within a school. Additionally, strategies to meet the identified student preferences can be implemented in the classroom with little or no cost implications. Implementation of these strategies influences the creation of a positive classroom climate and potential school improvement. Discussing these results and entering into a dialogue with students may allow the strength of perceptions to be further explored and increase the likelihood of creating congruence between preferred and actual classroom climate. Whilst the authors recommend that it is the school itself that engages in discussion with its pupils to determine their views and perspectives on the classroom environment, this is an area in which EPs can, and should, play an integral part in facilitating. Future study This study acknowledges limitations in its methodology and generalisability that may be addressed through future studies. Whilst this study draws on a moderate sample of students, the fact that it is based within the context of one single school raises issues about the generalisability of the findings. Furthermore, considering the evidence of Ryan and Patrick (2001) that preferred learning environments may alter with age, it is acknowledged that caution must be applied in attempting to generalise the results from the year groups sampled to older students within the school. Although a random sampling method was used to select participants for the focus groups, it is noted that the only variables considered within this study were year group and gender. Whilst students within this school are streamed into three ability levels for core subjects, the sampling technique did not take into account whether each ability stream was equally represented within the sample. Although evidence is presented within this study that neither gender nor year group has a significant overall effect on perception of factors, it is possible that factors unaccounted for such as ability or learning style may have impacted on the views expressed by participants and on the results obtained. Time constraints meant that only the perceptions and views of students were examined, and it is recognised that students represent only one side of the learning partnership. Future study exploring teacher perceptions would be beneficial in providing a fuller picture.

78

A. Gillen et al.

As this study relies on student self-report to measure the strength of perceptions, this allows no consideration of where these attitudes may originate, nor attempts to separate an individuals perception from the collective perceptions of groups and classes as a whole. Furthermore, if one acknowledges that the attitudes and perceptions of individuals are affected and effected through interaction with all aspects of an individuals environment, then variables in an individuals wider environment may also impact not only on the perceptions they have of the learning environment, but also on how they interact with the actual classroom environment. Therefore, consideration of alternative sources of information beyond simple self-report is needed to better understand the interaction of factors that impact on individuals perceptions, for example, classroom observation and in-depth student interviews. Although measures were taken during construction and piloting to increase questionnaire reliability it is noted that this study used an adapted questionnaire. Therefore, further investigation and refinement is recommended to increase internal consistency, reliability and validity if it is to be used for larger scale studies. Whilst this study supports the suggestion that students are best placed to indicate their preferred learning climate, it also raises further questions for future study. Further study is required to measure the extent that a match between preferred and actual classroom climate has on both the cognitive and affective outcomes for learning. In addition, study is needed to investigate the relationship between classroom climate and school climate and the reciprocal interaction between them. The impact that the overall school climate, for example, the policies and ethos, has on classroom climate will also have implications for the creation of a preferred-actual climate match.

Conclusion Classroom climate plays a major role in shaping the quality of school life and provides a significant opportunity not only for school professionals, such as teachers, but for EPs to become sensitised to important aspects of classroom life. Importantly, EPs are in a position of responsibility to act as a critical friend to schools to empower them to create their own positive change. By supporting schools to engage with pupil views of preferred classroom environments and raising awareness of the association between classroom climate and cognitive and affective outcomes of learning, it may be possible to influence the creation of the classroom climate that meets the needs of all individuals.

References

Adams, G.R., Gullotta, T.P., & Markstrom-Adams, C. (1994). Adolescent life experiences (3rd ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Cole Publishing Company. Adelman, H.S., & Taylor, L (1997). Addressing barriers to learning: Beyond school-linked services and full service schools. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67(1), 40842. Anderson, A., Hamilton, R.J., & Hattie, J. (2004). Classroom climate and motivated behaviour in secondary schools. Learning Environments Research, 7, 211225. Barbour, R.S. (2007). Doing focus groups (book 4 in qualitative methods kit). London: Sage. Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2002). Index for inclusion: Developing learning and participation in schools. Bristol: CSIE. Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77101.

Educational Psychology in Practice

79

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Byrne, D.B., Hattie, J.A., & Fraser, B.J. (1986). Student perceptions of preferred classroom learning environment. Journal of Educational Research, 80(1), 1018. Coolican, H (2004). Research methods and statistics in psychology (4th ed.). London: Hodder and Stoughton. Department for Education and Skills (DfES). (2004) Creating conditions for learning. Retrieved January 22, 2009, from http://nationalstrategies.standards.dcsf.gov.uk/node/95488 Dorman, J.P. (2008). Using student perceptions to compare actual and preferred classroom environment in Queensland schools. Educational Studies, 34(4), 299308. Fisher, D.L., & Fraser, B.J. (1983a). A comparison of actual and preferred classroom environment as perceived by science teachers and students. Journal of Research and Science Teaching, 20, 5561. Fisher, D.L., & Fraser, B.J. (1983b). Validity and use of classroom environment scale. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 5, 261271. Flutter, J. (2006). This place could help you learn: Student participation in creating better school environments. Educational Review, 58(2), 183193. Flutter, J., & Rudduck, J. (2004). Consulting pupils: Whats in it for schools? London: Routledge-Falmer. Fraser, B.J. (1998). Classroom environment instruments: Development, validity, and applications. Learning Environments Research, 1, 733. Freiberg, H.J. (1998). Measuring school climate: Let me count the ways. Educational Leadership, 56(1), 2226. Glover, D., & Law, S. (2004). Creating the right learning environment: The application of models of culture to student perceptions of teaching and learning in eleven secondary schools. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 15(34), 313336. Godfrey, J., Partington, G., Richer, K., & Harslett, M. (2001). Perceptions of their teachers by aboriginal students. Issues in Educational Research, 11, 113. Hughes, M., & Vass, A. (2001). Strategies for closing the learning gap. Stafford: Network Educational Press. Johnson, D.W., & Johnson, R.T. (1999). Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning (5th ed.). New York: Allyn & Bacon. Kelly, B. (2008). Frameworks for practice in educational psychology: Coherent perspectives and a developing profession. In B. Kelly, L. Woolfson & J. Boyle (Eds.), Frameworks for practice in educational psychology: A textbook for trainees and practitioners. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Khattar, M., Shirey, D., & Raustad, R. (2003). Cool & dry Dual-path approach for a Florida school. Ashrae Journal, 45(5), 5860. Killeen, J.P., Evans, G.W., & Danko, S. (2003). The role of permanent student artwork in students sense of ownership in an elementary school. Environment and Behavior, 35(2), 250263. Knight, G., & Noyes, J. (1999). Childrens behaviour and the design of school furniture. Ergonomics, 42(5), 747760. LaRocque, M. (2008). Assessing perceptions of the environment in elementary classrooms: The link with achievement. Educational Psychology in Practice, 24(4), 289305. Leong, F.T.L., & Austin, J.T. (2006). The psychology research handbook. London: Sage. Marshall, M.L. (2004). Examining school climate: Defining factors and educational influences (white paper, electronic version). Retrieved January 27, 2009, from Georgia State University Center for School Safety, School Climate and Classroom Management Website: http://education.gsu.edu/schoolsafety/download%20files/whitepaper_marshall.pdf Maslow, A.H. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York: Viking Press. McCracken, G. (1988). The long interview. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Miller, A., Ferguson, E., & Byrne, I. (2000). Pupils causal attributions for difficult classroom behaviour. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(1), 8596. Moos, R.H. (1979). Evaluating educational environments: Procedures, measures, findings and policy implications. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Osler, A. (2000). Childrens rights, responsibilities and understandings of school discipline. Research Papers in Education, 15(1), 4967.

80

A. Gillen et al.

Reid, R., Gonzalez, J.E., Nordness, P.D., Trout, A., & Epstein, M.H. (2004). A meta-analysis of the academic status of students with emotional/behavioural disturbance. The Journal of Special Education, 38(1), 130143. Reinke, W.M., & Herman, K.C. (2002). Creating school environments that deter antisocial behaviors in youth. Psychology in the schools, 39(5), 549559. Robson, C. (2002). Real world research. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Ryan, A.M., Gheen, M., & Midgley, C. (1998). Why do some students avoid asking for help? An examination of the interplay among students academic efficacy, teachers socio-emotional role and classroom goal structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 528535. Ryan, A.M., & Patrick, H. (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents motivation and engagement during middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 38(2), 437460. Sanorr, H. (2001). A vision for designing responsive schools. Raleigh, NC: National Clearinghouse for Educational Facilities & School of Architecture, North Carolina State University. Sink, C. (2005). My class-inventory short form as an accountability tool for elementary school counselors to measure classroom climate. Professional School Counseling. Retrieved March 15, 2009, from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0KOC/is_1_9/ai_n15792004 Topping, K.J. (2005). Trends in peer learning. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology, 25(6), 631645. Trickett, E.J., & Moos, R.H. (1973). Social environment of junior high and high school classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 65, 93102. Trickett, E.J., & Moos, R.H. (1974). Personal correlates of contrasting environments: Student satisfaction in high school classrooms. American Journal of Community Psychology, 2, 112. Woolner, P., Hall, E., Higgins, S., McCaughey, C., & Wall, K. (2007). A sound foundation? What we know about the impact of environments on learning and the implications for building schools for the future. Oxford Review of Education, 33(1), 4770. Zhang, K.C. (2008). Square pegs in round holes? Meeting the educational needs of girls engaged in delinquent behaviour. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 13(3), 179192.

Educational Psychology in Practice

81

Appendix 1. Creating a classroom for learning

I am I am in male Year 7 female Year 8

Strongly Strongly disagree Disagree Agree agree 1. It would help me to learn best if the tables were arranged in groups instead of rows 2. I would learn best if I DIDNT know what the lesson objective is 3. I would learn best if the displays on the wall had information to support my learning 4. I would learn best if the classroom was NOT colourful 5. I would learn best if I was comfortable in the classroom 6. I would learn best if the teacher gave lots of warnings but NO yellow cards 7. I would learn best if the teacher listened to my views 8. It would help me to learn best if I could choose who to sit with 9. I would learn best if I knew that I was doing well 10. I would learn best if the same rules were used for everyone 11. I would learn best if I ONLY got to work in the classroom 12. I would learn best if I could share ideas with my friends 13. I would learn best if I got the opportunity to work with different numbers of people 14. I would learn best if the activity was explained clearly 15. I would learn best if there were NO rewards for working well 16. I would learn best if the teacher offered help to me when I am stuck 17. I would learn best if the teacher told me the plan for the lesson at the start of the session 18. I would learn best if the teacher ONLY worked with one group in the lesson 19. I would learn best if I recorded my work in different ways e.g.,posters, drawings, computer 20. I would learn best if I could do practical activities e.g. drama, making things 21. I would learn best if the teacher ALWAYS used the same task at the start of the lesson 22. I would learn best if the lesson started quickly

(Continued.)

82

A. Gillen et al.

Appendix 1. (Continued.)

Strongly Strongly disagree Disagree Agree agree 23. I would learn best if there was NOTHING on the walls 24. I would learn best if I got free time when I finished my work 25. I would learn best if I felt comfortable asking the teacher for help 26. I would learn best if ONLY people who misbehaved were kept back after the lesson 27. I would learn best if I knew what the teacher expected me to do 28. I would learn best if I sat on my own 29. I would learn best if the teacher allowed me to make choices about my work 30. I would learn best if the teacher made decisions WITHOUT asking my opinion 31. I would learn best if the displays on the wall showed that my work is valued 32. I would learn best if the teacher told me who to work with 33. I would learn best if the classroom was tidy and well-organised

Appendix 2. Questionnaire coding

Questionnaire responses were coded with values 14 to allow further analysis. For statements positively supporting a theme, for example, I would learn best if I was comfortable in the classroom responses were coded as follows: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, 4 = Strongly Agree. Statements that were not seen to support a theme and for which disagreement was expected, for example, I would learn best if I DIDNT know what the lesson objective is were given reverse values: 4 = Strongly Disagree, 3 = Disagree, 2 = Agree, 1 = Strongly Agree.

Copyright of Educational Psychology in Practice is the property of Routledge and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Adult Learners and TechnologyDocument13 paginiAdult Learners and TechnologyTan Soon YinÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Pedagogy To Adult Training: A Comparison Research On The Roles of The Educator - School Teacher and Adult TrainerDocument10 paginiFrom Pedagogy To Adult Training: A Comparison Research On The Roles of The Educator - School Teacher and Adult TrainerTan Soon YinÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Pedagogy To Adult Training: A Comparison Research On The Roles of The Educator - School Teacher and Adult TrainerDocument10 paginiFrom Pedagogy To Adult Training: A Comparison Research On The Roles of The Educator - School Teacher and Adult TrainerTan Soon YinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Future of Adult EducationDocument4 paginiFuture of Adult EducationTan Soon Yin100% (1)

- The Future of Adult EducationDocument1 paginăThe Future of Adult EducationTan Soon YinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Psychological Foundations of CurriculumDocument12 paginiPsychological Foundations of CurriculumshielaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feelings and Moral Decision-Making: The Role of EmotionsDocument10 paginiFeelings and Moral Decision-Making: The Role of EmotionsJustin ElijahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading Comprehension Strategies: Make Connections Visualize Ask QuestionsDocument1 paginăReading Comprehension Strategies: Make Connections Visualize Ask Questionsnirav_k_pathakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prof. Ed 9 Act.5 Allan Balute Beed III-ADocument2 paginiProf. Ed 9 Act.5 Allan Balute Beed III-AAllan BaluteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notice Ret Result-July 2023Document2 paginiNotice Ret Result-July 2023webiisÎncă nu există evaluări

- 05 Etica Muncii - Aspecte Particulare in Domeniul MedicalDocument6 pagini05 Etica Muncii - Aspecte Particulare in Domeniul MedicalAlexis SacarelisÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9 - Lesson 4Document4 pagini9 - Lesson 4Lapuz John Nikko R.100% (2)

- Does Self Confidence Enhance Performance?: Riphah International UniversityDocument30 paginiDoes Self Confidence Enhance Performance?: Riphah International UniversityMuhammad TariqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Syllabus Forensic Psychology Spring 2016Document6 paginiFinal Syllabus Forensic Psychology Spring 2016Karla PereraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3 Lesson 4 For StudLearner Assessment in Literacy InstructionDocument3 paginiModule 3 Lesson 4 For StudLearner Assessment in Literacy Instructionvincentchavenia1Încă nu există evaluări

- Davao Doctora College Nursing Program Nursing Care Plan: General Malvar ST., Davao CityDocument3 paginiDavao Doctora College Nursing Program Nursing Care Plan: General Malvar ST., Davao CitySheryl Anne GonzagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prosocialness Scale For AdultsDocument2 paginiProsocialness Scale For AdultssarahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rafd 1Document4 paginiRafd 1api-432200858Încă nu există evaluări

- Improving Socio-Emotional Behavior with SkillstreamingDocument6 paginiImproving Socio-Emotional Behavior with SkillstreamingFELY B. BALGOAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Communication Techniques in Ice Age (2001Document3 paginiCommunication Techniques in Ice Age (2001Sserumaga JohnBaptistÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction to Supportive Therapy (SIDocument29 paginiIntroduction to Supportive Therapy (SINadia BoxerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nimhans - FIELD VISIT REPORTDocument4 paginiNimhans - FIELD VISIT REPORTvimalvictoria50% (2)

- Chapter 16 LeadershipDocument18 paginiChapter 16 LeadershipRafaelKwongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Level 12 Passage 4Document4 paginiLevel 12 Passage 4SSSS123JÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fighting For ConnectionDocument20 paginiFighting For Connectionkogaionro100% (1)

- Gender Development Theory and IdeologiesDocument22 paginiGender Development Theory and IdeologiesMichelle GensayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Haueter NSQ 2003Document20 paginiHaueter NSQ 2003Andra TheoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cot 1 Diass 2021 2022Document17 paginiCot 1 Diass 2021 2022KARLA DOLORE GRAPIZA100% (2)

- 16PF Personality Questionnaire GuideDocument31 pagini16PF Personality Questionnaire GuideFrances AragaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rabisanto Trishviola Joy C. CHAPTER 9 EXERCISESDocument6 paginiRabisanto Trishviola Joy C. CHAPTER 9 EXERCISESLiza Aingelica100% (1)

- Student DiversityDocument2 paginiStudent DiversityNathalie JaxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aniver Diaz-Maysonet, RGS6035.E2, Assignment IDocument4 paginiAniver Diaz-Maysonet, RGS6035.E2, Assignment IAniverÎncă nu există evaluări

- Victor Tausk - On MasturbationDocument20 paginiVictor Tausk - On MasturbationAndré Bizzi100% (1)

- Anthony Stevens - The Two Million-Year-Old Self PDFDocument80 paginiAnthony Stevens - The Two Million-Year-Old Self PDFCiprian Cătălin Alexandru0% (1)

- IMD 121 - Topic 2 - Self in CommDocument25 paginiIMD 121 - Topic 2 - Self in CommnanaÎncă nu există evaluări