Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Prof Ngugi Wa Thiongo Keynote Address Sat 29th June 2013

Încărcat de

The New VisionDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Prof Ngugi Wa Thiongo Keynote Address Sat 29th June 2013

Încărcat de

The New VisionDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

1

Makerere Dreams: Language and New Frontiers of Knowledge By Ngg wa Thiongo1

I feel truly grateful for the honor you have conferred on me by bringing me back to the scene of so many incredible memories. It was on this Hill that year after year, beginning in 1961, we celebrated the realization of a dream fought for in the streets of Dar, Nairobi and Kampala for over sixty years. The Makerere Students Guild, with its tradition of free and fair elections had already undermined the colonial practices but anticipated this moment. What the Guild had done for students who came from the three countries and even from beyond would now be the norm for the three countries. So we received the news of the independence of Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya as collective victory. Tanzania and Uganda were the first; but when finally Kenya came into the mix, we spilled into the streets of Kampala, all the way to the clock tower, and sang along with the masses of the three territories: Tulimtuma Nyerere Speech given at the programme for the University of East Africa 50th anniversary celebrations on 29th June 2013, Main hall, Makerere University

1

2 Kwa Uhuru, Kenya Uganda Tanganyika, Sisi twasaidiana We would put the names of the other two leaders, Kenyatta, and Obote in turns. In our euphoria, we allowed ourselves to dream of an imminent East African Union. This anniversary is then also that of a great moment in our history as East Africans; those of us who were on the Hill for the birth of new nations might well say with Wordsworths welcome of the French revolution:

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, But to be young was very heaven!

Even at a personal level, it was a moment of magic transformation. I entered Makerere in July 1959, a colonial subject of white settler state, and left in 1964, a citizen of an independent black Republic. During the same period, Makerere changed from being a colonial appendage of the University of London into an independent institution, the University of East Africa. The University of East Africa born on 28th june 1963 was formally dissolved on july 1 1970 but I like to think of it as transformation into three national universities, Nairobi and Dar, which in turn have spawned more universities and colleges in East Africa. There has thus been certain continuities but whatever the continuities, the degree certificates of the new dispensation would no longer draw their

3 legitimacy from their appendage London. So to celebrate the historic moment of a transformation of an institution that boasts of, among its distinguished alumini, Presidents, Prime Ministers, Doctors, Agriculturists, professors, diplomats, writers, musicians, artists, sportsmen and women who span every region of Africa and the globe, is to commemorate a great achievement by every measure possible. It is an achievement born of a century of dreams that has been Makerere since its foundation in 1922. Because of the regions Makerere had served, bringing on to one Campus students from Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Malawi, even Zimbabwe, Makerere was also site and symbol of dreams we still have to dream, and fight for: the dream of East African Union or better still, a politically and economically united Africa. Makerere was the site of another dream. I was one of a group that included John Nagenda, Peter Nazareth, Jonathan Kariara, David Rubadiri, Micere Mugo to cite a few, who wrote stories and poems and essays for the English Departments magazine Penpoint. In a way Makerere of my time was a personal paradise: the Kenya I came from was under a state of emergency with the dead and the tortured often lay in the streets. We lived under what Fanon calls a nervous condition of the colonized in a white settler town. Makerere opened the space of my imagination. It was here, on this Hill, that I wrote my first two novels, Weep not Child and The River Between, and numerous short

4 stories. My play, The Black Hermit, was written for the specific purpose of celebrating Ugandas independence. East African writers of my generation were largely Makerere products. In addition to spawning East African writers, this Hill hosted the historic gathering of African writers of English expression in June 1962. They came from all corners of the continent: Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, J P Clark and Christopher Okigbo from Nigeria; Lewis Nkosi, Eskia Mphahlele, Arthur Mamaine, Bloke Modisane from South Africa; with John Nagenda, Jonathan Kariara, Rajat Neogy and I representing East Africa. In attendance were also Langston Hughes from America and Arthur Drayton from the Caribbean, giving the gathering a truly Pan African dimension. There had been great gathering of black writers before but they met everywhere else but Africa, Rome in 1956 and Paris in 1959. Makereres was the first ever gathering of black writers in Africa. These writers would later give us whats the nearest thing to a genuine Pan African intellectual article: the book, African literature. When Achebe passed on recently he was mourned all over the continent. His book, Things Fall Apart, the text most discussed at the conference alongside that of Dennis Brutus of South Africa, is read in all Africa. The work of others like Okot pBitek and Wole Soyinka, and that of the generations that have followed, Dangarembga, Ngozi Adichie and Doreen Baingana are equally well received as belonging to

5 all Africa. Thus if Makerere was the site and symbol of an East African intellectual community, Makerere marked the birth of literary Panafricanism. It was at that conference that the questions of who we are as Africans, nationals, continentals, or even diasporics, was raised; It so happened that every single participant in that Makerere event wrote in English; the product of our imagination derived its legitimacy from the linguistic appendage to London. The physical empire may have come to an end but the very triumph of that conference was the mark of the continuity of metaphysical empire. Language is at the heart of the metaphysical empire. So it is not just creative writing and literature: Scholarship in and about Africa has continued being an integral part of the European metaphysical empire. At this 50th anniversary it behooves us, the inheritors and custodians of that scholarship, to glance at the implications of that continued appendage to Europe. We have to look at the scholarship that has emerged since our formal declaration academic independence from London. And the scholarship out of Makerere and its sister institutions is not tiny. Graduate in virtually every academic field at the University of East Africa and the other higher institutions of learning arising from it, are to be found in every corner of the globe. I was once on a visit to a Canada, in a region I thought not part of the beaten track, when I got a call and an invitation to meet with Makerereans. I

6 dont even have to go to Canada and other places. Thursday night I entered the business lounge of the British airlines at Heathrow airport feeling alittle worn out as a result of a sleepless night across the Atlantic, when my eye caught an African person about to take his fruit salad. We nodded at each other, started talking. His name was Dr Jones KYAZZE, former UNESCO representatitve to United Nations and presently a member of Mutesa 1 Royal University Council. He had been attending Rotary International Convention, in Lisbon and so, like me, he was in transit. But guess what! He joined Makerere two years after I left; and he was a Northcorter like me. But unlike me whose degree certificate still said, University of London, his was fully from the University of East Africa. So we are talking about a scholarship which has made and continues to make significant mark in depth and breadth in Africa and the world. But scholarship, any scholarship, is not a neutral activity, even in its conceptual vocabulary. No matter in whose hands, scholarship impacts how people look and view social reality, including history and culture. For centuries, cartographers conditioned people to think that Africa is smaller than Europe. Yet as some maps have shown, Africa is bigger than a combination of Europe, USA, China, India, Argentina, and New Zealand put together. Scholarship started and helped perpetuate the notion of Africa north of Sahara, including Egypt as European, and the South as being Africa proper, the horde of tribes in perpetual warfare. Hegel emphatically declared that history, the enlightenment of reason and science, had bypassed his proper Africa which remained enveloped in the

7 dark mantle of the night, an image no doubt arising from his reading of colonial travel narratives that talked about Dark or Darkest Africa. Hegels image becomes a truth in the grandiloquent stupidity of Trevor Roper of Oxford when in the 1960s he claimed that Africa had only darkness to exhibit prior to European colonial presence. Since darkness was not a subject of history, the history of Africa begun with European colonialism. Some of these attitudes have changed in large part because of enlightened scholarship, but still, the nomenclature of North and South of the Sahara, and the vocabulary of warring tribes, have become enshrined in the annals of scholarship and popular parlance. An article describing my coming had to specify that I was from Kikuyu tribe. The continued evaluation of events in Africa through the prism of the tribe, tribes and tribesmen, masks and distorts the real issues driving African realities. First is the differential definition of communities. Why are a quarter million Icelanders a nation; and ten million Ibos, a tribe? Why are 4 million Danes a nation; and twenty million Yorubas, a tribe? Even when scholars and journalists dont use the word nation in reference to European peoples, they at least refer to them by the names they call themselves. Thus they talk about the English, the Germans, the French, the Chinese, or simply, Chinese people, English people. But when it comes to Africa the words tribe and tribesmen must be appended to the reference. An Englishman gets a nobel prize in chemistry. He is rightfully referred to as Mr So and so, an English man or woman. An African gets a nobel prize in chemistry, and he is editorialized as Mr so and so, an X or Y tribesman or tribeswoman. In other continents, heads of government are referred as Presidents and Prime Ministers of their specific countries. African heads of state must be editorialized as President so and so yes, but an x or y Tribesman.

8 A recent Reuters news service piece even talked about tribal blood!! What color is tribal blood or bloodshed? The word is so tainted by its colonial usage that whatever cognitive scientific meaning it might once have had, has all been but subsumed under its pejorative colonial umbrella. The word has become a code. Once the readers see it, they assume that the actors are doing whatever they are, because of an inherent tribal mark in their character. In the process the real issues of governance, democracy, patterns of property ownership and economic control, uneven regional development, corruption, get lost. It is as if a particular person is corrupt because of his genetic pool, labeled tribe. This vocabulary, permeating European studies of Africa to this day, was invented by colonial Anthropology, in its beginnings at least, the study of the insider by the outsider, for the consumption of fellow outsider. He gathered information and put it in his language and we cannot blame him for that. What we can question is the fact that our various fields of knowledge of Africa are in many ways rooted in the entire colonial tradition of the outsider looking in, gathering and coding knowledge with the help of native informants, and then storing the final product in a European language for consumption by those who have access to that language. In other words, we still collect intellectual items and put them in European language museums and archives and people have to dig into those languages in order to access knowledge about ourselves. Our knowledge of Africa is largely filtered through European languages and their vocabulary. Is it not time that our scholarship stopped finding legitimacy in European languages in the same way that Makerere, as an institution, stopped deriving its legitimacy from appendage to London?

9 How many historians, African and non-African alike, who have ever written even a single document in an African language? How many researchers have even retained the original field notes in words spoken by the primary informant? At a recent conference in Leeds, in response to my question as to whether any of the more than a hundred scholars had ever written a page in an African language in their entire scholarship on Africa, only three hands were raised. For more than a page, not one hand was raised. I asked a question that I always ask. Can you imagine a Professor of French history who did not know a word of French? But in the case of Africa, either on the continent or abroad, one can get employment as an African specialist without having to demonstrate any competence in any African language. I have seen prizes been announced specifically for the promotion of African literature. But only on condition that the entries are not in an African language. Can you imagine the horror that it would raise if someone offered a prize for the promotion of French literature but only on condition that the participants write it in Zulu? French Literature in Zulu? Unfortunately even within the continent we have come to accept that view that whats African is only so if it is in English or French. Both African and non-African scholars can claim to be specialists of this or that aspect of African history, culture, society, politics, without accepting the linguistic challenge and the responsibility. There are those of course who will argue that African languages are incapable of

10 handling complexities of social thought, that it has no adequate vocabulary, in short, African languages, like their speakers, are riddled with poverty. This objection was long ago answered by one of the brightest intellects from Africa, Cheikh Anita Diop, when he argued that no language had a monopoly of cognitive vocabulary, that every language could develop its terms for science and technology. He tried to debunk the claims of poverty of African languages, the inadequacy of words and terms. It should not be forgotten that even English and French had to overcome similar claims of inadequacy as vehicles for philosophy and scientific thought as against the then dominant Latin. African languages need is a similar commitment from African intellectuals Some cynics will respond and assert that an African language cannot sustain a written intellectual production. Books written and published in Danish with four million speakers number thousands and fill up the shelves of many libraries. The Yoruba people number more than ten million. But intellectual production in the two languages is very different. How come that ten million Africans cannot sustain such a production whereas four million Danes can? Icelanders number about two hundred and fifty thousand. They have one of the most flourishing intellectual productions in Europe. What a quarter of a million people can do, surely ten million people can also accomplish. Today we talk of Greek and Latin intellectual heritage and forget that these productions were city in origins. The vaunted Italian renaissance and its rich and varied heritage in the arts and architecture and learning were largely from the different regions of Rome, Florence, Mantua, Venice and Genoa. What the vernaculars of these city states, principalities and regions by way of intellectual production have been able to do, can be done by any other

11 similarly situated languages. The question remains: what would be the place of European languages in African scholarship? No matter how we may think of the historical process by which they came to occupy they place the now do in our lives, it is a fact that European languages (principally English, French and Portuguese) now carry immense deposits of some the best in literary and general African thought. They are granaries of African intellectual productions. These languages have enabled a common visibility of African presence. These languages also enable conferences like this with attendants from different regions and language groups. The latter in fact defines best the mission we should assign to French and English. Use them to enable dialogue among African languages and visibility of African languages in the community of world languages instead of their being a tool of disabling by uprooting intellectuals and their production from their original language base. Use English and French to enable and not to disable. The question of dialogue among African languages through translations directly or via a third language is vital. But currently there is a dismissive arrogance when it comes to African languages and what they have to offer. This then is the challenge of our scholarship today: How best to really connect with the African continent, in the era of globalization? For African scholars, we cannot afford to be intellectual outsiders in our own land. We must re-connect with the buried alluvium of African memory and use it as a base for the further planting of African memory on the continent and in the world. This can only result in the empowerment of African languages and cultures and make them pillars of a more self-confident Africa

12 ready to engage the world, through give and take, but from its base in African memory. African intellectuals must do for their languages and cultures what all other intellectuals in history have done for theirs. In nutshell:If you know all the languages of the world and you dont know your mother tongue or the language of the culture of the community into which you are born, that is enslavement. But if you know your language and add all the languages of the world, that is empowerment. The choice for us is between intellectual enslavement and and intellectual empowerment and of course I hope we choose the path of empowerment. When Makerere school of fine art was first founded, the school used to import clay from London. Good art could only come out of European soil. It was only when artists like Elimo Njau and Sam Ntiro came to the scene that they said: let the children paint. Use whatever material is around you including from Banana plants. Thus begun a kind of renaissance of contemporary East African art. The scholar however cannot do this alone. He or she needs a publisher. Everybody knows how frustrating it is to write manuscript and then have to put on a shelf for lack of a publisher who is even willing to look at it. But the scholar and the publisher cannot do it alone. They need enlightened government language policies. Unfortunately even African governments are buying into the recipe for Africa intellectual suicide. I dont know how much the world and other monetary forces of globalization have to do with it, but African governments are turning their back on African languages. They deny them resources. This is a far cry from the days of Kwame Nkrumah who on assuming power in 1957 set up Bureau for African languages. Or of Julius Nyerere who did so much for Kiswahili in terms of policy but additionally did his bit in translating

13 Shakespeare into Kiswahili. Julius Nyerere, a product of Makerere, was also the first and only Chancellor of the University of East Africa. I wish each and every African country would emulate the idea of setting up a Central Bureau of African languages that would see into the development and relationships of African languages in their own country. In the particular case of East Africa, I would like to see a three language policy: strengthen mother tongue as the foundation; add Kiswahili as the common language; and then English. In terms of books, I would love to see more translations among those three and of course between African languages as a whole. Scholars of the new generation: let us extend the dream that was always Makerere and venture forth and open new frontiers of knowledge. Let Africa open new spaces in the economy, politics, and culture. Let Africa be at the forefront in the renaissance of a new more inclusive humanity. Let ourselves be the beginning of new selves. Then will our dreams merge with that millions of working people in our countries and Africa that Martin Carter, from Walter Rodneys country, once wrote about in his poem looking at your hands: I have learnt from book dear friend, of men dreaming and living and hungering in a room without light who could not die since death was too poor who did not sleep to dream but dream to change the world and so, if you see me looking at your hands, listening when you speak,marching in your ranks you must know, I DO NOT SLEEP TO DREAM BUT DREAM TO CHANGE THE WORLD

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Commentaries on Contemporary Nigerian PoliticsDe la EverandCommentaries on Contemporary Nigerian PoliticsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ali A. Mazrui - Pan-Africanism and The Intellectuals Rise, Decline, and Revival PDFDocument22 paginiAli A. Mazrui - Pan-Africanism and The Intellectuals Rise, Decline, and Revival PDFCelina Castro Jaimes0% (1)

- Apartheid PresentationDocument5 paginiApartheid PresentationVictoriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines For School Level PlanningDocument64 paginiGuidelines For School Level Planningbanduwgs100% (1)

- Friday Daily Nation Uhuru3Document53 paginiFriday Daily Nation Uhuru3nbwogora5752Încă nu există evaluări

- "After Mandela: The Struggle For Freedom in Post-Apartheid South Africa" by Douglas FosterDocument10 pagini"After Mandela: The Struggle For Freedom in Post-Apartheid South Africa" by Douglas FosterOnPointRadioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Freedom, Festivals and Caste in Trinidad After Slavery: A Society in TransitionDe la EverandFreedom, Festivals and Caste in Trinidad After Slavery: A Society in TransitionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mbeki Thabo TamboDocument9 paginiMbeki Thabo TamboKwame Zulu Shabazz ☥☥☥Încă nu există evaluări

- What Was The Nature of Resistance To ApartheidDocument11 paginiWhat Was The Nature of Resistance To Apartheidspellas83% (6)

- CJ Maraga ProfileDocument14 paginiCJ Maraga ProfileAnonymous 3QQW2A6vyyÎncă nu există evaluări

- My Life's Footprints:: Rhoda Peace Tumusiime's AutobiographyDe la EverandMy Life's Footprints:: Rhoda Peace Tumusiime's AutobiographyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rights After Wrongs: Local Knowledge and Human Rights in ZimbabweDe la EverandRights After Wrongs: Local Knowledge and Human Rights in ZimbabweÎncă nu există evaluări

- Names: Biko, Stephen Bantu Born: 18 December 1946, King Williams Town, Eastern Cape (Now Eastern Province)Document5 paginiNames: Biko, Stephen Bantu Born: 18 December 1946, King Williams Town, Eastern Cape (Now Eastern Province)stÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nigeria's Aborted 3Rd Republic and the June 12 Debacle: Reporters' AccountDe la EverandNigeria's Aborted 3Rd Republic and the June 12 Debacle: Reporters' AccountÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Road to Reform: The Politics of Zimbabwe's Global Political AgreementDe la EverandThe Hard Road to Reform: The Politics of Zimbabwe's Global Political AgreementÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daniel Branch (2007), "The Enemy Within: Loyalists and The War Against Mau Mau in Kenya", Journal of African History, 48 (2007), Pp. 291-3Document25 paginiDaniel Branch (2007), "The Enemy Within: Loyalists and The War Against Mau Mau in Kenya", Journal of African History, 48 (2007), Pp. 291-3TrepÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roger S. Boulter - Afrikaner Nationalism in Action - F. C. Erasmus and South Africa's DefencDocument23 paginiRoger S. Boulter - Afrikaner Nationalism in Action - F. C. Erasmus and South Africa's Defencuchanski_tÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mau Mau Uprising Torture Claims Against UKDocument4 paginiMau Mau Uprising Torture Claims Against UKrahul181Încă nu există evaluări

- FURLONG, PATRICK - Apartheid, Afrikaner Nationalism and The Radical Right - Historical RevisionisDocument18 paginiFURLONG, PATRICK - Apartheid, Afrikaner Nationalism and The Radical Right - Historical Revisionisuchanski_tÎncă nu există evaluări

- White Narratives: The depiction of post-2000 land invasions in ZimbabweDe la EverandWhite Narratives: The depiction of post-2000 land invasions in ZimbabweÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frantz Fanon: Philosophy, Praxis and The Occult ZoneDocument37 paginiFrantz Fanon: Philosophy, Praxis and The Occult ZoneTigersEye99100% (1)

- The African National Congress and the Regeneration of Political PowerDe la EverandThe African National Congress and the Regeneration of Political PowerÎncă nu există evaluări

- When a State Turns on its Citizens: 60 years of Institutionalised Violence in ZimbabweDe la EverandWhen a State Turns on its Citizens: 60 years of Institutionalised Violence in ZimbabweÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Return of MakhandaDocument30 paginiThe Return of MakhandaLittleWhiteBakkieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nyayo House PDFDocument88 paginiNyayo House PDFomuhnateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Un Nished Struggles Against Apartheid: The Shackdwellers' Movementin DurbanDocument38 paginiUn Nished Struggles Against Apartheid: The Shackdwellers' Movementin DurbanTigersEye99Încă nu există evaluări

- Nelson Mandela Story by (Media Action Plan - Org)Document41 paginiNelson Mandela Story by (Media Action Plan - Org)Morris BilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unpacking the Impact of Land Dispossession for Effective Land Restitution Research in South AfricaDe la EverandUnpacking the Impact of Land Dispossession for Effective Land Restitution Research in South AfricaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Melancholia of Freedom: Social Life in an Indian Township in South AfricaDe la EverandMelancholia of Freedom: Social Life in an Indian Township in South AfricaEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- How Europe Underdeveloped AfricaDocument15 paginiHow Europe Underdeveloped AfricaAdaeze IbehÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Protest to Challenge, Vol. 1: A Documentary History of African Politics in South Africa, 1882-1964: Protest and Hope, 1882-1934De la EverandFrom Protest to Challenge, Vol. 1: A Documentary History of African Politics in South Africa, 1882-1964: Protest and Hope, 1882-1934Încă nu există evaluări

- The Promise of Justice. Book One. The Story: King Justice Mpondombini Sicau's struggle for the amaMpondo KingdomDe la EverandThe Promise of Justice. Book One. The Story: King Justice Mpondombini Sicau's struggle for the amaMpondo KingdomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visionary Schools: Liberating At-Risk Students, Transforming a NationDe la EverandVisionary Schools: Liberating At-Risk Students, Transforming a NationÎncă nu există evaluări

- A House in Zambia. Recollections of the ANC and Oxfam at 250 Zambezi Road, Lusaka, 1967-97: Recollections of the ANC and Oxfam at 250 Zambezi Road, Lusaka, 1967-97De la EverandA House in Zambia. Recollections of the ANC and Oxfam at 250 Zambezi Road, Lusaka, 1967-97: Recollections of the ANC and Oxfam at 250 Zambezi Road, Lusaka, 1967-97Încă nu există evaluări

- TWC2 Newsletter May-Jun 2011Document14 paginiTWC2 Newsletter May-Jun 2011Transient Workers Count TooÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Civil Strife to Peace Building: Examining Private Sector Involvement in West African ReconstructionDe la EverandFrom Civil Strife to Peace Building: Examining Private Sector Involvement in West African ReconstructionÎncă nu există evaluări

- David Anderson Huw Bennett Daniel Branch (2006) - A Very British Massacre. History Today, August 2006.Document7 paginiDavid Anderson Huw Bennett Daniel Branch (2006) - A Very British Massacre. History Today, August 2006.TrepÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2016 Abantu Book Festival ProgrammeDocument16 pagini2016 Abantu Book Festival ProgrammeSA Books100% (1)

- Presentation - Sacli 2018Document10 paginiPresentation - Sacli 2018Marius OosthuizenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lost in Democracy: “An Analytical Inquest into Africa’S Difficulties with Democracy and the Prospects of Finding Alternative Systems of Government That May Work Without Hitches.”De la EverandLost in Democracy: “An Analytical Inquest into Africa’S Difficulties with Democracy and the Prospects of Finding Alternative Systems of Government That May Work Without Hitches.”Încă nu există evaluări

- Statement by Dr. Francis Mading DengDocument10 paginiStatement by Dr. Francis Mading DengAbyeiReferendum2013100% (1)

- Tafelberg Short: Awakening the Lion: The case of The Lion Sleeps TonightDe la EverandTafelberg Short: Awakening the Lion: The case of The Lion Sleeps TonightÎncă nu există evaluări

- Famous Social Reformers & Revolutionaries 5: Nelson MandelaDe la EverandFamous Social Reformers & Revolutionaries 5: Nelson MandelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Origins of Non-Racialism: White opposition to apartheid in the 1950sDe la EverandThe Origins of Non-Racialism: White opposition to apartheid in the 1950sÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stories of the Liberation Struggles in South Africa: Mpumalanga Province, Part IiDe la EverandStories of the Liberation Struggles in South Africa: Mpumalanga Province, Part IiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zimbabwe's Trajectory: Stepping Forward or Sliding BackDe la EverandZimbabwe's Trajectory: Stepping Forward or Sliding BackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Volume5 PDFDocument463 paginiVolume5 PDFdavid mendibleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Origins and Solutions to Africa’S Rebel Conflicts (The Seirra Leone Chapter): Politicians Centered ApproachDe la EverandOrigins and Solutions to Africa’S Rebel Conflicts (The Seirra Leone Chapter): Politicians Centered ApproachÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Museveni's CHOGM Business SpeechDocument12 paginiPresident Museveni's CHOGM Business SpeechThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Museveni's 2023/24 Budget SpeechDocument7 paginiPresident Museveni's 2023/24 Budget SpeechThe New Vision0% (1)

- State of The Nation Address 2023Document51 paginiState of The Nation Address 2023The New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Museveni End of Year Message 2023Document11 paginiPresident Museveni End of Year Message 2023The New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Executive Order No. 3 of 2023Document18 paginiExecutive Order No. 3 of 2023The New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Museveni's Heroes Day 2022 SpeechDocument9 paginiPresident Museveni's Heroes Day 2022 SpeechThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Museveni's Speech As Uganda Celebrated 60 Years of IndependenceDocument31 paginiPresident Museveni's Speech As Uganda Celebrated 60 Years of IndependenceThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Museveni's End of Year AddressDocument34 paginiPresident Museveni's End of Year AddressThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Successful Candidates General Duties & DriversDocument25 paginiList of Successful Candidates General Duties & DriversThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Museveni's Speech On World Teachers Day 2020Document12 paginiPresident Museveni's Speech On World Teachers Day 2020The New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- State of The Nation Address 2022Document32 paginiState of The Nation Address 2022The New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba's Speech at Thank You Concert in EntebbeDocument3 paginiGen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba's Speech at Thank You Concert in EntebbeThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

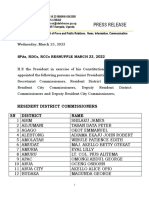

- SPAs, RDCS, RCCs ReshuffledDocument12 paginiSPAs, RDCS, RCCs ReshuffledThe New Vision100% (3)

- Final Admission List of Students To Government Health Training CollegesDocument298 paginiFinal Admission List of Students To Government Health Training CollegesThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ruling Aine Godfrey Kaguta Sodo V NRM & AnotherDocument23 paginiRuling Aine Godfrey Kaguta Sodo V NRM & AnotherThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- President's Statement To Kampala Bomb BlastsDocument3 paginiPresident's Statement To Kampala Bomb BlastsThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- 58TH Independence Anniversary Speech by President Yoweri MuseveniDocument13 pagini58TH Independence Anniversary Speech by President Yoweri MuseveniGCICÎncă nu există evaluări

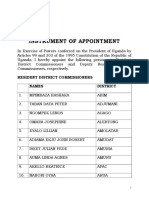

- New RDCs & Deputy RDCsDocument16 paginiNew RDCs & Deputy RDCsThe New Vision100% (2)

- Dorothy Kisaka Inauguration SpeechDocument9 paginiDorothy Kisaka Inauguration SpeechThe New Vision100% (1)

- Cabinet 2019/20Document13 paginiCabinet 2019/20The New Vision80% (5)

- Presidential Address On The National LockDownDocument22 paginiPresidential Address On The National LockDownMujuni Raymond Carlton QataharÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Lady's Address On The Reopening of SchoolsDocument9 paginiFirst Lady's Address On The Reopening of SchoolsThe New Vision100% (1)

- H.E. The President's Message To BuzukuuluDocument25 paginiH.E. The President's Message To BuzukuuluThe New Vision100% (1)

- President Museveni's CPC SpeechDocument15 paginiPresident Museveni's CPC SpeechThe New Vision100% (1)

- Salva Kiir Easter MessageDocument3 paginiSalva Kiir Easter MessageThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018 State of The Nation Address UgandaDocument30 pagini2018 State of The Nation Address UgandaThe Independent MagazineÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Yoweri Museveni's Speech at TICADDocument10 paginiPresident Yoweri Museveni's Speech at TICADThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Museveni's Address To The Mozambique ParliamentDocument16 paginiPresident Museveni's Address To The Mozambique ParliamentThe New VisionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Private Admission List 2017/18Document1.052 paginiPrivate Admission List 2017/18The New Vision95% (19)

- President Yoweri Museveni's Speech at The Commissioning of The Hoima-Tanga PipelineDocument8 paginiPresident Yoweri Museveni's Speech at The Commissioning of The Hoima-Tanga PipelineThe New Vision100% (1)

- French Course IntroductionDocument37 paginiFrench Course IntroductionAadya SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Taught CoursesDocument9 paginiEnglish Taught CoursesmousaviniashayanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mika GlossaryDocument29 paginiMika GlossaryMika Jean CallaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- C1 Apprendre Du VocabulaireDocument4 paginiC1 Apprendre Du VocabulaireAlexandra CandreaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gannello CVDocument2 paginiGannello CVapi-392859826Încă nu există evaluări

- Argyro Kanaki in PressDocument23 paginiArgyro Kanaki in PressargyroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anh 9Thí Điểm (UNIT 7- Unit 12)Document36 paginiAnh 9Thí Điểm (UNIT 7- Unit 12)Minh TuấnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pimsleur French I PDFDocument29 paginiPimsleur French I PDFbios200983% (6)

- Escuela Municipal Gustavo Bisquertt Popeta – Rengo English WorksheetDocument2 paginiEscuela Municipal Gustavo Bisquertt Popeta – Rengo English WorksheetCarolina Pérez Silva100% (1)

- French School VocabularyDocument7 paginiFrench School VocabularymomoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multilingualism Cultural Identity and EdDocument11 paginiMultilingualism Cultural Identity and EdIBRAHIM MAJJADÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3-Minute French 25 Lesson SeriesDocument117 pagini3-Minute French 25 Lesson SeriesAFAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role of English in FranceDocument2 paginiRole of English in FranceArli MiscalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Offer 2020-2021 - Edito 2-1Document18 paginiCourse Offer 2020-2021 - Edito 2-1Jessica Jeongah ChoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Countries Where English Is The ONLY Official Language2Document1 paginăCountries Where English Is The ONLY Official Language2Candy BereniceÎncă nu există evaluări

- AEF 2 File Test 5Document4 paginiAEF 2 File Test 5william75% (4)

- 12.S8 061608 Fpod101Document4 pagini12.S8 061608 Fpod101Dante MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Y PDF - Google Docs: Bilingual Visual Dictionary Russian EnglishDocument3 paginiY PDF - Google Docs: Bilingual Visual Dictionary Russian EnglishFernanda VilelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- TheDutchLanguageinBritain 1550 1702 ASocialHistoryoftheUseofDutchinEarlyModernBritain JobyDocument468 paginiTheDutchLanguageinBritain 1550 1702 ASocialHistoryoftheUseofDutchinEarlyModernBritain Jobytzarabis100% (1)

- GROSJEAN 1982 - Life With Two Languages An Introduction To Bilingualism (Livro)Document388 paginiGROSJEAN 1982 - Life With Two Languages An Introduction To Bilingualism (Livro)Karina Borges Lima100% (2)

- Duolingo GuideDocument239 paginiDuolingo GuidePrabha T100% (1)

- TLB108 04 - 02Document2 paginiTLB108 04 - 02truck diesel solutionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exploring French WorkbookDocument136 paginiExploring French WorkbookWes Ryan63% (8)

- Explore the Beauty of PeruDocument17 paginiExplore the Beauty of PeruAlejandro García GómezÎncă nu există evaluări

- English As A Second LanguageDocument6 paginiEnglish As A Second LanguageczirabÎncă nu există evaluări

- Countries, Nationalities and LanguagesDocument2 paginiCountries, Nationalities and Languagesbvhmot200Încă nu există evaluări

- Language Policy in A Multilingual SocietyDocument11 paginiLanguage Policy in A Multilingual SocietyBeny Pramana PutraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test Bank For Human Geography People Place and Culture 10th Edition Erin H Fouberg Alexander B Murphy Harm J de BlijDocument18 paginiTest Bank For Human Geography People Place and Culture 10th Edition Erin H Fouberg Alexander B Murphy Harm J de Blijdenisedanielsbkgqyzmtr100% (20)

- File Test 1 - InglesDocument7 paginiFile Test 1 - InglesCris Álvarez RomeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arguments For and Against Quebec SeparationDocument2 paginiArguments For and Against Quebec SeparationAthena Huynh25% (4)