Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Working With Bilingualism: The Aim of Our Care.

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in Practice0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

133 vizualizări3 paginiChavda P, Helsby L. (2003)

The advantages of bilingualism are such that a speaker's overall competency may be more than a sum of parts. This article reports that recognising and facilitating this in group therapy not only has benefits for the children concerned, but brings parents and other staff on board too. Language groups were run in Leicester for two groups, each with 7 boys, with a bilingual background of English and Gujarati spoken at home. At the start of the groups the parents completed a questionnaire which looked at their expectations and their understanding of language issues. The structure and activities of the therapy sessions and homework (translated into Gujarati for parents) are described. Children were encouraged to access and name items in both languages and to use home language outside the home setting.

Titlu original

Working with bilingualism: the aim of our care.

Drepturi de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentChavda P, Helsby L. (2003)

The advantages of bilingualism are such that a speaker's overall competency may be more than a sum of parts. This article reports that recognising and facilitating this in group therapy not only has benefits for the children concerned, but brings parents and other staff on board too. Language groups were run in Leicester for two groups, each with 7 boys, with a bilingual background of English and Gujarati spoken at home. At the start of the groups the parents completed a questionnaire which looked at their expectations and their understanding of language issues. The structure and activities of the therapy sessions and homework (translated into Gujarati for parents) are described. Children were encouraged to access and name items in both languages and to use home language outside the home setting.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

133 vizualizări3 paginiWorking With Bilingualism: The Aim of Our Care.

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeChavda P, Helsby L. (2003)

The advantages of bilingualism are such that a speaker's overall competency may be more than a sum of parts. This article reports that recognising and facilitating this in group therapy not only has benefits for the children concerned, but brings parents and other staff on board too. Language groups were run in Leicester for two groups, each with 7 boys, with a bilingual background of English and Gujarati spoken at home. At the start of the groups the parents completed a questionnaire which looked at their expectations and their understanding of language issues. The structure and activities of the therapy sessions and homework (translated into Gujarati for parents) are described. Children were encouraged to access and name items in both languages and to use home language outside the home setting.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 3

groups

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE SPRING 2003 +8

t has been well documented that group

therapy for children is an effective way of

working (Brigman et al, 1992). It allows par-

ents to see their child in relation to other

children and gain a different perspective so

that, instead of solely focusing on their

childs difficulties, they can begin to appreciate

their strengths. However, when working in a busy

community clinic, it is very easy to select children

for group therapy on the basis of high caseload

numbers, rather then looking carefully at individ-

ual needs. This is particularly problematic for

bilingual children and their families as, when

selecting them for group therapy, their overall

language competencies may not be taken into

account. When a childs full abilities are not

acknowledged, parents are automatically margin-

alised and unable to participate fully in the group

therapy experience.

l

The advantages of

bilingualism are such that

a speakers overall

language competency

may be more than a sum

of parts. Panna Chavda

and Laura Helsby find that

recognising and facilitating

this in group therapy not

only has benefits for the

children concerned, but

brings parents and other

staff on board too. Here,

they tell us what they did

and why they did it.

you are pannng

therapy groups

have bngua

cents

want to measure

eectveness

Read ths

The vibrant, multicultural City of Leicester has

many minority ethnic groups represented, and a very

high bilingual speaking community. We find bilin-

gual children can be included in general groups with

monolingual children where the aim is to improve

areas such as social skills, attention and listening.

However, we wanted to offer more targeted groups

with a focus on the specific needs of bilingual chil-

dren with language development difficulties.

When planning our groups for a busy inner city

clinic, we used the Malcomess (1999) decision-

making loop (figure 1) to identify the clinical

need, in other words the why of therapy. When

we ask why we do things with clients - as well as

what we do and how we do it - it enables us to focus

on a more functional model of service delivery

rather than just a diagnostic, medical model. It

allows us to tailor care to individuals and to begin to

look at the outcome of intervention. We then arrive

at a care aim which leads to goal setting, interven-

tion and review with a measure of effectiveness.

We grouped individuals according to their care

aims then identified care aims for the overall

group. Our level of input included the planning

phase (two weeks), running the groups (six

weeks), and the post-group report writing, review

and contact with schools (two weeks).

We ran two language groups for children chosen

on criteria of age, language difficulties, parental

commitment and support. All came from a bilingual

background with English and Gujarati spoken at

home. The first group had seven boys aged 5-8 years,

presenting with mainly moderate language difficulties

across both languages. The second group also had

seven boys, this time aged 7-10 years, with higher level

language difficulties across both languages.

Insight

At the start of the groups the parents completed a

questionnaire (adapted with permission from

Hulme et al, 2001). We wanted to look at parents

expectations of the language group and to gain

insight into their understanding of language issues.

The questionnaires were discussed with parents

in Gujarati and, if needed, in English. Several

themes emerged:

1. Many children with language 100% disagreed

problems are simply lazy.

All of the parents felt the difficulties their children

experienced with language were genuine.

Working with

bilingualism:

Panna Chavda Laura Helsby

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE SPRING 2003 +,

groups

2. Playing with your child is 100% agreed

important in learning language.

3. Parents play a vital role in the 100% agreed

treatment of language disorder.

While all agreed that parents as well as other mem-

bers of the family play an important part in the

treatment of language difficulties, some found it

difficult to fully support therapy due to time

restraints, lack of ideas and language barriers.

4. Language disorder is a 40% agreed,

new type of a problem; it 40% disagreed,

was not around years ago. 20% did not know

Although some parents knew about language dis-

order, over half did not know it existed.

5. Gujarati children have 70% disagreed,

language problems because 30% agreed

they have to learn to use or were unsure

more than one language.

Most parents related this question to their child.

A small number felt that learning Gujarati and

another language can initially cause confusion,

and that a child may find it difficult. The majori-

ty saw that the difficulties their child experienced

were not due to learning Gujarati and another

language. Comments included, It is the parents

attitude that causes the problem not the lan-

guage. Some parents reported that they had

been advised to speak in English to their child,

which gave them the impression that this would

resolve the language difficulties.

6. Learning to speak more 70% disagreed,

than one language causes 10% agreed and

language problems. 20% were unsure

Similarly, the majority felt that learning to speak

more than one language generally causes no

problem, and cited their own successful experi-

ences. They acknowledged that it may initially

take some children longer to learn two languages

but in the long-term there are more advantages

associated with it. They also noted the importance

of learning the home language for bonding with

the family members and for cultural identity.

7. Children with language 50% agreed,

difficulties often have 40% disagreed and

problems with their behaviour. 10% were unsure

The majority who agreed with this related it to

the children being unable to express themselves,

leading to frustration.

8. Children with language 95% disagreed and

disorder are stupid and will 5% agreed about

have problems getting a the difficulty in

good job when they grow up. getting a job

The majority disagreed. They felt that, with enough

help, their childrens language difficulties should

not hinder them in the future, and they were opti-

mistic about the children doing well. They felt the

attitude of other people such as teachers, parents

and employers would be important.

9. Attending the group 50% agreed and 50%

will cure my childs felt it would help the

language problem. language difficulty but

not cure it.

Half of the parents were hoping that attending

the group would cure the language problem.

Half did not feel the group would provide a cure

but that it would help the child to learn and give

ideas to parents on how to deal with the lan-

guage problem and think differently.

10. Speech and language 100% disagreed and

therapy does not work. felt it helped their child

The majority were very confident that speech and

language therapy

to date had made

a big difference

in the childrens

learning. A

number felt that

school had a vital

role to play and

that getting the

right help at

school was

i m p o r t a n t .

Parents said that

they had more

ideas on how to

work with their

childs language. They felt early detection of the

problem was important.

The questionnaire gave qualitative information

about the parents perception of their childs lan-

guage difficulty. Discussion with them during the

completion of the questionnaire gave insight into

the understanding of our role as speech and lan-

guage therapists, and meant we could reinforce cer-

tain perceptions and change others through the

group.

Closer bond

The groups ran in a local clinic for 45 minutes once

a week over a six week block with two bilingual

English / Gujarati speech and language therapists.

The group children who are statemented have

school-based language support assistants.

Holding the group over the school term from

January to March enabled these assistants to

attend without the burden of a larger time com-

mitment. They observed the group dynamics and

activities and got involved where appropriate.

They were an extremely useful resource and

helped to develop a very important closer bond

between schools and the speech and language

therapy service. In turn, the assistants reported

how beneficial it was to have time to reflect and

to practise the activities during the week.

After the six weeks the remainder of the term

time was given over to re-running the group tasks

in school at the discretion of the language support

assistants.

The groups had a structure each week:

A gelling game to encourage group cohesion

(for example, (a) fruit salad - objects or pictures

were given to each child, two items were called

out, and the children with those items swapped

places; (b) passing a ball with a verbal activity).

Activities to develop attention and listening

skills in a group setting via Sounds of the World

listening tape (UNICEF, no longer available).

The core of the sessions consisted of tasks based

on themes. Examples of themes were advertising

(for older children), countries and languages spo-

ken, food and drink, animals, transport, shapes,

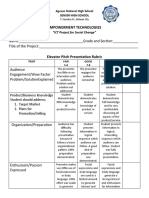

Figure 1 Clinical Decision-Making Loop (Episode of care)

Identify Clinical Needs

Intervene

Review

goals and

measure

effectiveness

Set goals for

intervention

Kate Malcomess, 1999

the aim of our care

and training given so we take advantage of the

rich possibilities offered by bilingualism and

ensure that the children receive therapy appropri-

ate to their clinical needs.

Panna Chavda is Clinical Lead Speech and Language

Therapist (Bilingualism) and Laura Helsby Chief

Speech and Language Therapist with Leicester City

West NHS Primary Care Trust. Address for correspon-

dence: Childrens Speech and Language Therapy

Service, Prince Philip House, St Matthews Health and

Community Centre, Leicester LE1 2NZ.

References

Asian Book of Nursery Rhymes. Mantra

Publishing. (ISBN 1852697016).

Brigman, G., Lane, D. & Switzer, D. (1992)

Teaching Children Success Skills.

Journal of Educational Research 92

(6) 232- 329.

Cummins, J. (1984) Bilingualism and

Special Education: Issues in

Assessment and Pedagogy.

Multilingual Matters, Clevedon.

Hulme, S., Rahman Jennings, Z. &

Thomas, D. (2001) Alternative

Methods. Bulletin of the Royal

College of Speech & Language

Therapists August, 10-12.

Malcomess, K. (1999) Measuring

Effectiveness. Workshop. (See

Malcomess, K. (2001) The reason for

care. Bulletin of the Royal College of

Speech & Language Therapists

November, 12-14.)

Masidlover, M. & Knowles, W. (1979)

Derbyshire Language Scheme.

Derbyshire County Council.

Sage, R. (2000) Class Talk. Stafford Network

Education Press.

Useful Resources

* The Bilingual Family Newsletter is written by and

for parents. See www.multilingual-matters.com,

e-mail marjukka@multilingual-matters.com or

write to Multilingual Matters, Frankfurt Lodge,

Clevedon Hall, Victoria Road, Clevedon, England

BS21 7HH.

Online catalogue: www.bilingual-supplies.co.uk.

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE SPRING 2003 o

groups

words from one language are used in a sentence in

another language. So we said, I like baath for din-

ner for I like rice for dinner.

Positive and valuable

The children needed to feel they could use their

home language outside the home setting to help

with their communication. This approach increased

their confidence and self-esteem and enabled

them to use both their languages in a positive and

valuable manner. In addition, the language support

assistants and parents saw first-hand, or through

feedback in the homework discussion, how suc-

cessfully both languages could be used to help

bilingual children with language difficulties.

Having parents taking part in the groups with

feedback given in their home

language ensured the positive

aspects of bilingualism were

conveyed, and allowed code

switching and other normal fea-

tures of bilingual communication

to be reinforced.The language

support assistants were able to

understand the importance of

using the childs overall commu-

nicative abilities and to value the

learning of the home.

During each session, we kept a

record our observations of the

childrens language and interac-

tion while completing the tasks.

This information was used when

we completed a communication

skills rating questionnaire

adapted from The

Communication Opportunity Group Scheme

(COGS) (Sage, 2000), which is used in

Leicester to promote effective communica-

tion in schools. We found it a very useful

tool to measure baseline performance for

bilingual children, and will be using it as an

ongoing measure of change and as a basis

for discussion with parents and teachers.

The rating scale has four main areas: general

skills, formal conversation, formal presentation

(speech/writing) and non-verbal communi-

cation. It is rated from high competency to

no evidence of the skill on a scale of 1-5.

The communication skills rating alongside

conventional assessment provides a much

more holistic picture of the childrens lan-

guage strengths, weaknesses and progress,

allowing the mapping of skills over time

across both languages and along different

parameters.

Where there are fewer bilingual children

it can be problematic to have bilingual groups for

their specific languages but, for effective therapy,

it is better to include children who have the same

home language and English, rather than children

of many different languages. In areas where there

are no bilingual speech and language therapists,

co-workers and interpreters should be accessed

Do we seect cents or groups on

the bass o ther need - or our

need to get through our caseoad'

Do we oer a servce whch

takes account o the strengths

o a cents background'

Do we promote code swtchng,

exca borrowng and namng

n two anguages wth our

bngua cents'

Reectons

colours. We also had activities to develop giving

and receiving requests based on the Derbyshire

Language Scheme (Masidlover & Knowles, 1979)

and time sequences related to simple stories.

Maps of the world, cross cultural food items (pic-

tures and false foods) and advertisements from

local community and high street shops were useful

resources.

Gujarati nursery rhymes (adapted from Mantras

book of Asian Nursery Rhymes).

Although we had the structure and themes to

follow, there was flexibility for the pupils to intro-

duce and lead a topic of their choice.

Homework was given at the end of each session.

This was translated in Gujarati and discussed with

parents. This formed one of the most valuable

aspects of the intervention as it allowed the par-

ents to understand the what and why of the

groups. Parents who were present during the

group sessions benefited most from watching the

strategies the speech and language therapist

employed during the group, as they were able to

try these out at home. The aims of the group and

the homework set were, as a result, more thor-

oughly understood, and compliance on complet-

ing the homework was high.

Cummins (1984) discusses the idea of a common

underlying proficiency model in bilingualism. We

know there is more than enough room inside our

thinking quarters for two or more languages, and

research also suggests there is transfer between

languages. For example, a child taught multiplication

and subtraction in one language does not need to

have those concepts re-taught in the second lan-

guage, only the vocabulary to reproduce it. We

aimed not to do the tasks in one language then

another, but to use the

natural discourse of a

bilingual speaker accord-

ing to the situation to

facilitate vocabulary

and word finding. The

session reflected the

childrens natural bilin-

gual use of language

where code switching

and lexical borrowing is

a normal feature. All

the tasks were therefore

done in English and

Gujarati, led by the

bilingual Gujarati speak-

ing therapists.

In vocabulary work,

for example with our

food theme, we encour-

aged the children to

access and name items in both languages to build

up semantic links and facilitate word recall. Code

switching (for example, I have been to India, hu

rikshawma beto meaning I have been to India,

I sat in a Rikshaw) was used naturally through-

out. Names of food items were used in conversa-

tion as an example of lexical borrowing, where

We aimed not to do

the tasks in one

language then

another, but to use

the natural

discourse of a

bilingual speaker

according to the

situation to facilitate

vocabulary and

word finding.

Homework was

translated in Gujarati

and discussed with

parents. This formed

one of the most

valuable aspects of

the intervention as it

allowed the parents

to understand the

what and why of

the groups.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Winning Ways (Winter 2007)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Winter 2007)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Document78 paginiMount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Speech & Language Therapy in Practice75% (8)

- Turning On The SpotlightDocument6 paginiTurning On The SpotlightSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Document1 paginăIn Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Autumn 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Autumn 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalDocument2 paginiIn Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winning Ways (Summer 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Summer 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowDocument1 paginăHere's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeDocument1 paginăHere's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ylvisaker HandoutDocument20 paginiYlvisaker HandoutSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Summer 10Document1 paginăHere's One Summer 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Winter 10Document1 paginăHere's One Winter 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Document2 paginiIn Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologyDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applying Choices and PossibilitiesDocument3 paginiApplying Choices and PossibilitiesSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Spring 11Document1 paginăHere's One Spring 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- My Top Resources (Winter 11) Clinical PlacementsDocument1 paginăMy Top Resources (Winter 11) Clinical PlacementsSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief... : Supporting Communication With Signed SpeechDocument1 paginăIn Brief... : Supporting Communication With Signed SpeechSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Practical FocusDocument2 paginiA Practical FocusSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Pathways: Lynsey PatersonDocument3 paginiNew Pathways: Lynsey PatersonSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding RhysDocument3 paginiUnderstanding RhysSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Winter 11Document1 paginăHere's One Winter 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief Winter 11Document2 paginiIn Brief Winter 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One I Made EarlierDocument1 paginăHere's One I Made EarlierSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Exequiel F. Guhit English 1O 10 - St. Francis Week 5Document3 paginiExequiel F. Guhit English 1O 10 - St. Francis Week 5Ju Reyes80% (5)

- Procedure Text GILANGDocument3 paginiProcedure Text GILANGMar KudidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Corpus Approach To Analysing Gerund Vs InfinitiveDocument16 paginiCorpus Approach To Analysing Gerund Vs Infinitivesswoo8245Încă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum Vitae of Anvita Abbi, PH.D.: Chairperson: Centre For LinguisticsDocument20 paginiCurriculum Vitae of Anvita Abbi, PH.D.: Chairperson: Centre For LinguisticsKABILAMBIGAI VÎncă nu există evaluări

- Passé ComposéDocument5 paginiPassé Composéalex1971Încă nu există evaluări

- Elevator Pitch Rubrics (ICT For Social Chnage)Document2 paginiElevator Pitch Rubrics (ICT For Social Chnage)Dran OteroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foreign Language InstituteDocument2 paginiForeign Language Institutedckapoorasfl9846Încă nu există evaluări

- Pretest in Oral CommunicationDocument4 paginiPretest in Oral CommunicationmariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Language Policy and PlanningDocument82 paginiIntroduction To Language Policy and PlanningFE B. CABANAYANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Animal House RapDocument3 paginiAnimal House RapMariana FontÎncă nu există evaluări

- текшеруучу суроолорDocument12 paginiтекшеруучу суроолорNuri Dm FlowerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toy Enc 1102 Spring2021Document25 paginiToy Enc 1102 Spring2021api-355676368Încă nu există evaluări

- Milton Model EbookDocument17 paginiMilton Model EbookJustinTangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Russian-English English-Russian Dictionary Русско-английский англо-русский словарь (PDFDrive)Document628 paginiRussian-English English-Russian Dictionary Русско-английский англо-русский словарь (PDFDrive)Đani NovakovićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physicians Use of Inclusive Sexual Orientation Language During Teenage Annual VisitsDocument9 paginiPhysicians Use of Inclusive Sexual Orientation Language During Teenage Annual VisitsTherese Berina-MallenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ingles Trabalho FeitoDocument8 paginiIngles Trabalho FeitoSamuel ZefaniasÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Teaching Manual (Contents & Index)Document314 paginiEnglish Teaching Manual (Contents & Index)Constanza U. RedshawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hyphens & ParenthesesDocument47 paginiHyphens & ParenthesesMuhammad Nazri SalimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3shape Grammars1Document94 pagini3shape Grammars1OSHIN BALASINGH100% (1)

- ExamDocument10 paginiExamhell oÎncă nu există evaluări

- A2 EDU20001 Developing LiteracyDocument10 paginiA2 EDU20001 Developing Literacynaima fadilyyt7i8 please 0tlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form of Passive: Example: A Letter Was WrittenDocument7 paginiForm of Passive: Example: A Letter Was WrittenMhel LimbagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food CultureDocument3 paginiFood Culturejai sreeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task 1 & Task 2 Highly Important Sentence StructuresDocument22 paginiTask 1 & Task 2 Highly Important Sentence StructuresRizwan Bashir100% (1)

- 0510 s08 Ms 11+12Document13 pagini0510 s08 Ms 11+12Hubbak Khan100% (1)

- Interrogative Sentences (Oraciones Interrogativas)Document4 paginiInterrogative Sentences (Oraciones Interrogativas)Mario Javier Ganoza MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- O'Grady and Dobrovolsky Eds, 1997 Contemporary Linguistics 3rd EdDocument27 paginiO'Grady and Dobrovolsky Eds, 1997 Contemporary Linguistics 3rd EdLourdes SerrizuelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language Ecology Sociolinguistic Environment Contact and DynamicsDocument10 paginiLanguage Ecology Sociolinguistic Environment Contact and Dynamicssharma_maansiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oceanic Linguistic TodayDocument59 paginiOceanic Linguistic Todayraoni27Încă nu există evaluări

- Volume 26 Legon Journal of The Humanities PDFDocument174 paginiVolume 26 Legon Journal of The Humanities PDFRobin100% (1)