Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Allen, Sarah - The Cultivated Self - Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

Încărcat de

sem2u2Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Allen, Sarah - The Cultivated Self - Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

Încărcat de

sem2u2Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Rhetoric Review, Vol. 29, No.

4, 364378, 2010 Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0735-0198 print / 1532-7981 online DOI: 10.1080/07350198.2010.510058

SARAH ALLEN

Rhetoric Review, Vol. 29, No. 4, Jul 2010: pp. 00 1532-7981 0735-0198 HRHR

University of Northern Colorado

Rhetoric Review

The Cultivated Self: Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

As Crowley and Hawhee explain in Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students, debate as we know it today is nothing more than spat, mere theater because conceptions of opinion-as-identity stands in the way of rhetorical exchange. However, in Foucaults Self Writing and in Montaignes Essais, another version of subjectivity in writing is conceptualized and practicedone where the subject is constituted in practices at work in the care of the self. In this version of subjectivity, the productive exchange of ideas would be possible.

The Cultivated Rhetoric Review Self: Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

Last spring I had a student who, in the essays he submitted to me and to the class, jeered at the rape and murder of women.1 When I first met with the student to talk about the content in his essays, he was hostile: But this is who I really am! he exclaimed. I have a twisted sense of humor! At the time of our conference, we were reading works by Peter Elbow and bell hooks on voice, and in response to those works, he felt empowered to finally be able to say what [he] really think[s] in a paper. Unfortunately, according to the texts we were reading, which he cited to make his argument that I should allow this kind of content in his essays, he was indeed justified in voicing what he saw as his true self, even if the voicing silenced/marginalized others. In taking this case to several of my rhetoric and composition colleagues, the most consistent bit of advice I got from them was to steer the student away from thinking about his self-on-the-page as a constitutive act of voice (a textual representation of the real writer) and, instead, as a construction of ethos. With this shift in perspective, the assumption was that he would be able to see the selfon-the-page from the perspective of a reader, as his audience might see it. Then,

364

The Cultivated Self: Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

365

we could talk about the effectiveness of that ethos, how persuasive (or in this case, how offensive/frightening) it might be, and how to revise that ethos so that it would be more effective. Of course, what was implied in their advice, too, was that the student would then see the error of his ways, for, inevitably, he would find that the more effective ethos would be one that aligned with the values, morals, and codes of conduct deemed acceptable by an audience of . . . me . . . and, ideally, of upper-level English majors. The problem with this implication is, I hope, obvious: that the student would be required to conform to institutionally accepted values. This would not necessarily be a problem if those values only involved what makes writing good. But, lets not kid ourselves: The production of good writing is often intimately intertwined with, if not dependent on, the demonstration of the values of what makes a good person (thus the importance of ethos). However, in this particular case, the practice of disciplining a student into conforming to my notions of the good person smacks of a kind of liberalism gone wrong, for by asking a student to examine the ethos in his writing in order to deploy it more effectively, Im not just asking him to think critically and to write persuasively. Im also teaching him to conform to particular sociopolitical values. As such, I become a part of a system where the disciplining practices of our field take a turn toward the silencing practices of intellectual tyranny. Undoubtedly, Ive been on the receiving end of the same kind of intellectual tyranny and known, first hand, its benefits. It comes with the disciplining of grad school and then of becoming a professional. But the difference is that I choosehowever thoughtfully or naivelyto participate in the disciplining practices that now constitute the self that I recognize as the academic. Admittedly, some of that choosing happened without much awareness, but it was still a choice (for example, I knew my belief system was dramatically changing over the course of my PhD program). My student whom I would be discipliningvia grade reductions, for exampleinto conforming to more institutionally approved values (all in the name of effective ethos) has little choice if he values his GPA and all that students typically associate with their GPAsa good career, a valued/validated intellect, respect from others, and so forth. No doubt one could argue (as I often do myself) that its more important to be teaching my students to be attentive, respectful, socially responsible, and critical thinkers than to give them the space to be their own persons, which in my students case, would translate to being a person who participates in and perpetuates some of the most horrible isms of the world. Still, by teaching said values, how am I much better than that kind of person? More importantly, how am I doing what I promise to do with every new group of students: support, mentor, and challenge?

366

Rhetoric Review

Certainly, I knowand can arguethe difference between the self-righteousness that I invoke for my own purposes and the self-righteousness articulated in the rapecelebrating paper written by my student. I can argue that I am attempting to insert myself into discourses that perpetuate dangerous hierarchies and abuse, that I am trying to create a disruption, trying to break a chain forged over centuries of problematic thinking, talking, and acting along perilous conceptions of gender roles. But after making such attempts over a decade of teaching, I know for certain that if students think you are trying to silence them by challenging their beliefs/arguments, your attempts at disruption will only persuade them to shut down the exchange (ironically, often in the name of self-expression). In part, the problem seems to stem from our modern-day conceptions of debate and self, under which we have subsumed the conception of ethos. To be more specific, as Crowley and Hawhee explain to rhetoric students in their textbook Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students, debate as we know it today is often nothing more than spat, mere theater (3) because the conception of opinion-as-identity stands in the way of rhetorical exchange (5). In other words, according to Crowley and Hawhee, Americans tend to link a persons opinions to her identity. We assume that someones opinions result from her personal experience, and that those opinions are somehow hersthat she alone owns them (5). Thus folks tend to get very upset when their opinions are challenged, because the assumption is that their opinions are not all that are at stake in a debate; their identities, their selfhood, are. The presence of this assumption about opinion-as-identity in our own classes, pedagogies, and even scholarship is, arguably, the residual effect of an institutional purchase (with all the associated advertising for) of Romanticism and its hero, the Romantic subject. Borrowing the wording of John Muckelbauer in his work on imitation, were seeing the effects of the institutional emergence of romantic subjectivity, an ethos that emphasizes creativity, originality, and genius (62). One of those effects can be seen in the fact that conceptions of the writer, especially, are bound up in that belief in opinion-as-identity. To explain, we tend to see our subjectivities as constructed via our experiences, meaning that we see our subjectivities as entirely dependent on our ability to have and to interpret those experiences, as if what we experience and how we experience happen in a subject-object relation (that is, me vs. the experience). When we enter into a relation with the object-that-is-experience, we interpret it and in that act become agents. In turn, life becomes a series of events to be interpreted, interpretations that we can possess by imposing a narrative of that life (enter creativity), a narrative that is the product of our unique perspectives (enter originality), which are unique because of the unique constellation of experiences that have been interpreted by our individual selves (enter genius).

The Cultivated Self: Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

367

The upshot of this tangle is that we get to see ourselves as agents in this worldnot simply as actors but as unique entities that necessarily interpret and possess experience differently. What we also get is the belief that my perspective is who I am and that any challenge to that perspectivewhich, ironically, can be represented by groups to which I belong, like institutions, families, and so forthis a threat to my very existence. I hope it seems now more obvious that there is not much room for debate in such a belief about subjectivity. One can easily see this belief in opinion-asidentity at work in my students argument about his voice, his true/honest self, on the page. One can easily see it in the failed attempts on my part to interject in a discourse in which that voice is implicated. And one can see it in the truncated conceptions of ethos today: where in order for ethos to be effective, the writer must construct the self-on-the-page in such a way that it represents the values and mores accepted by its audience so that said audience can find affirmation of its own identity in the argument (as if thats what any argument doesaffirm or negate identities). If we, as rhetoric and composition scholars and teachers, really find any usefulness for argument and debate, or for rhetoric more generally, then the failures we face due to this particular conception of subjectivity are, frankly, unacceptable. For the purposes of this article, then, I would like to make visible a bygone way of approaching the self and others which might suggest possibilities for the present (Rabinow, Introduction xxvii)possibilities for how one might conceive of subjectivity in writing. To do this work, I turn to the work of Michel Foucault. The particular practices that will be examined in this project are described best in Foucaults article, Self Writing. In it he introduces self writing as a series of practices in which the writer participates to constitute and/ or cultivate his/her self. Through this exploration of Foucaults work on subjectivity, particularly of subjectivity in writing, I hope to describe a compelling and progressive study of subjectivity in writingone that makes possible the kind of exchange that Crowley and Hawhee advocate for in their work. Of course, Foucaults work provides only the system of thought, the skeleton, so to speak, around which one can shape the conception/articulation of an actual subject-in-writing. In order to provide a few actual subjects-in-writing, in which to examine relevant writing practicesin order to flesh out for this particular version of subjectivityI have chosen to take up the essays of Montaigne. Ive chosen Montaignes essays for a few important reasons: (1) because the essay is often deemed the last free space for self-expression/exploration and (2) because Montaigne is considered the father of the genre. More importantly, given the fact that his essays are often quoted to support the concept of opinionas-identity, his work seems an interesting and valuable place to start.2

368

Rhetoric Review

Self Writing In Self Writing, Foucault looks at the role of writing in philosophical cultivation of the self just before Christianity: its close link with companionship, its application to the impulses of thought, its role as a truth test (208). Specifically, he studies the practices of self writing in the works of Seneca, Plutarch, and Marcus Aurelius. What he finds is that the close link with companionship, as well as self writings application to the impulses of thought and its role as a truth test, are all elements found in the works of these writers. These three elements should sound familiar to essayists and essay scholars, for essay-writing involves conversing with a reader (companionship), writing the mind on the page (the application of writing to the impulses of thought), and experimenting with and/or exploring ideas (truth tests). The difference, though, between Foucaults articulation of these elements and more common articulations from essay scholars/writers, is that the former involves the privileging of practicesof conversing, of applying, of testingnot the sovereignty of the writer, as the creator of a companionship, as the creator of an application of writing to thought, as the creator of a truth test. To explain, much of Foucaults work focuses on several modes of objectivation, modes through which the subject subjects his/her self. Subjecting, however, does not simply imply making into an object, as the term objectivation might suggest. Rather, a rendering happens in that subjecting, so that the subject-onthe-page is constituted, not reflected or constructed. The distinction I want to make here between constituted and constructedand as I understand it in Foucaults workis one of agency: that is, saying a subject is constructed puts more emphasis on the writer who is writing (an actor doing the constructing) while constituted emphasizes the processes of subjection, the practices within which a subject is subjected.3 For example, the practices of self writing, at least pre-Christian self writing, are driven not by the creative genius or essence of the expressive writer but by the cultivation of the art of living.4 Foucault argues that according to the Pythagoreans, the Socratics, and the Cynics, the art of living can only be acquired with exercise, via a training of the self by oneself (Self Writing 208). This training is a way of caring for the self. Foucault states, In Greek and Roman texts, the injunction of having to know yourself was always associated with the other principle of having to take care of yourself, and it was that need to care for oneself that brought the Delphic maxim [know thyself] into operation (Technologies 20). In other words, self writing is not simply the process of figuring out what I already know, who I already am. Rather, care of the self, which involves multiple practices that shape the self, makes possible knowledge

The Cultivated Self: Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

369

of ones self (not the other way around, which is the assumption I see in my students now, for example). To explain, Foucault describes two different forms of writing that are modes of caring for the self, training the self, in writing. They are the hupomnemata and correspondence. For the purposes of this study, the focus will be on the hupomnemata because correspondence is a mode with specific limitations that would not fit the tradition of the essay.5 The hupomnemata, on the other hand, were written for the purpose of meditation, which is precisely what Montaignes essays were written for (this will be explained further in the coming pages). Additionally, the emphasis on meditation makes for interesting possibilities for thinking about the practices that constitute the subject-on-the-page. The Hupomnemata Examples of hupomnemata include account books, public registers, or individual notebooks serving as memory aids. These were used as guides for conduct. In Self Writing Foucault states, They constituted a material record of things read, heard, or thought, thus offering them up as a kind of accumulated treasure for subsequent reading and meditation (209). These texts were not simply memory maintenance. They were a material and a framework for the exercises of reading, rereading, meditating, [and] conversing with oneself and with others (210). In other words, these texts were not written out, (re)read, and referenced simply for the sake of recollection but, to quote Plutarch, to [elevate] the voice and [silence] the passions like a master who with one word hushes the growling of dogs (qtd. in Self Writing 210). So, for example, I keep a notebook of quotations Ive gathered from readings, of ideas Ive discovered through encounters with other texts, and so on. In some cases Ive reread and written more at length (Ive meditated on) the quotes/material gathered there, and that meditation has helped to hush the growling of dogs; in other cases the quotes sit alone on the page without much/any meditation applied to them. But the collection, itself, still constitutes hupomnemata. More broadly, the purpose of the hupomnemata is to make ones recollection of the fragmentary logos transmitted through teaching, listening, or reading, a means of establishing a relationship of oneself with oneself, a relationship as adequate and accomplished as possible (211). As to how that collection becomes a means to establishing a relationship of oneself with oneself, the process is complicated. To start by putting this relationship into more general terms (and work down to the specifics), the truths constituted in these texts are, through the practice of meditation, planted in the soul; that is, the soul must make them not merely its own but itself (210, my emphasis). To understand this

370

Rhetoric Review

process and to practice it, one must shift away from thinking about subjectivity in terms of opinion-as-identity and toward a different version. In the former version of subjectivity, the assumption that the soul makes these truths its own would have been true. Students would either accept and own the truths they encountered in readings, or they would reject them. In turn, when writing about those truths, the writer becomes the owner of those beliefs by interpreting and then rendering them through her own unique perspective. However, in stating that the soul does not merely make particular truths its own but makes them itself, the distinction is as follows: that the soul does not create, possess, and/or wield truths; rather, the soul is constituted in the practices of reading, rereading, and writing about those readings (that is, meditating)the practices made possible by the hupomnemata.6 Essay-writing, however, is often used in contemporary writing classrooms as a tool for revealing the innermost self, as a tool for confession of what is hidden/ secret, of what is oppressed/silenced in the selfthe stuff of the soul that we own but have not owned up to, so to speak. Despite this common conception of the essay, though, in Montaignes work confession does not actually seem to be the purpose. Rather, Montaignes essays work much like the hupomnemata, which were written for a purpose that is nothing less than the shaping of the self (Self Writing 211). Montaigne admits to this project, too, in Of Giving the Lie. He states, Painting myself for others, I have painted my inward self with colors clearer than my original ones. I have no more made my book than my book has made me (504). In effect, he is saying here that in writing his book, he has not confessed a self; instead, the producing has written his self. 7 The Practices of Reading and Writing: Returning to the Hive Montaigne describes at least a part of the process of the constituting of self as such: I have not studied one bit to make a book; but I have studied a bit because I had made it, if it is studying a bit to skim over and pinch, by his head or his feet, now one author, now another (Of Giving 505, my emphasis). Accordingly, it is not that he studied other works and then wrote about them; rather, in the making of the book, Montaigne meditated on other authors works, and they became a part of the constitution of his self. For example, in Of Books he talks about transplanting original ideas (for example, from the works of Seneca) into his own soil and confound[ing] them with his own (296). Again, self writing is not simply an act of appropriation of others works. It is a complex practice, which involves reading and rereading and constantly writing, so that in these operations, the self is constituted. In describing this process of meditation (that is, of reading and writing), Foucault uses the

The Cultivated Self: Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

371

metaphor of returning to the hive.8 Writing is a way to gather thoughts and is an exercise of reason that counters the great deficiency of stultitia, which endless reading may favor (Self Writing 211). Most academics are familiar with the great deficiency of stultitia in trying, for example, to research for a paper, presentation, book, or essay. It is the experience(s) of mental agitation, distraction, change of opinions and wishes, and consequently weakness in the face of all the events that may occurall brought about by too much reading and not enough writing. The hupomnemata, however, provide the writer with the means for fixing acquired elements, so that the past is constituted in a way that allows the writer the possibility of turning back, of meditating on that past (212). I can imagine that the hupomnemata, then, can be used like personal diaries or writers notebooks, much like Didion describes in On Keeping a Notebook, where writers collect material for reflection and/or for future writings.9 However, its worth noting that theres a difference between collections like Didions notebooks and my students diaries. The latter, at least according to my students, are often simply collections of confessions, which have very little use-value beyond the act of confession (and in fact, are oftentimes impossible to understand after any considerable lapse of time because of their opaquely self-referential prose). The writer rarely returns to them. The hupomnemata, on the other hand, are supposed to be guidebooks. So, for example, I used to keep a quote journal, which was comprised of lines from texts I found to be particularly compelling. I returned to them when I needed themusually for ideas for paper topics, but also for good advice when confronting complicated situations in my personal relationships, work, and so forth. Of course, the diary could be used the same way if the writer made a commitment to returning to the entries, to reflecting on them, even to rewriting/ amending them. I have seen creative writing teachers ask students to keep journals, for example, so that the students would cultivate their writer-selves more often (that is, beyond formal class assignments) and so that they would have a body of material to work on and from in those formal assignments. Point being, the hupomnemata are not just another practice in pop psychology. They are not simply collections of affirmations I repeat to myself in order to empower myself. Rather, in the act of meditating on those texts, a disciplining, a cultivating, of self occurs, for in that act, a relationship of oneself with oneself is established, a relationship that should be as adequate and accomplished as possible, that makes possible a relation between the two (subjected) subjects that work agonistically toward an end that belongs to an ethics of control (Care 65). The process is a bit like Heracles wrestling the Nemean lion, which (if I may make a somewhat obscure reference) is described in The Mythic Tarot as a symbolic struggle between Heracles and his ego. It is an encounter of oneself to

372

Rhetoric Review

oneself, the latter of which is in relation to the former but not as its reflection, not even as its equal. Rather, the two are constituted in the encounter and struggle agonistically toward an end that is the conversion of the self. Thus the end that belongs to an ethic of control is not an end where Heracles slays the lion or vice versa. Instead, he masters it. It is submitted, as is he, in the encounter that involves a series of practicesperhaps of tactical maneuvers, of fatal bites and pinched veins. In fact, in The Mythic Tarots reading of the story, neither player can be negated or rejected; to convert/transform, neither can be killed. To come at this relationship another way (and, thus, hopefully to understand it better), one of the ways one can cultivate that relationship so that it is as adequate and accomplished as possible is to practice turning back, fixing the past in such a way that it can be studied. In this practice the writer can, in turn, prepare for the future. In Of Presumption Montaigne states, Not being able to rule events [or Fortune], I rule myself, and adapt myself to them if they do not adapt themselves to me (488). In other words, he cannot control the future, so instead, he composes a self, ideally, a self that can adapt to the events that may happen in the future. In describing how one can work toward this self, in Of Experience, he states, He who remembers the evils he has undergone, and those that have threatened him, and the slight causes that have changed him from one state to another, prepares himself in that way for future changes and for recognizing his condition (822). In that remembering, in meditating on the past, and in preparation for the future, he practices control, and because of it, he will also be able to practice control in whatever future struggles he encounters.

The Practice of the Disparate To the question, again, then: How does one write the self, particularly a more vigilant or less susceptible self? In part, one does so by returning to the hive, as shown above, by collecting material, reading it repeatedly, reflecting on it, and writing about it. However, it is not enough to simply return to the hive. In order for the writing to workin order for it to actually create a more disciplined or at least a different personthe truths (the maxims) of the writings being meditated on and of the writings generated in that meditation must be tested. Again, self writing is not repeating affirmations (I am a good scholar. I am a good scholar). In order for it to work, in order for that relationship between writer and page to transform the self of the writer, truths (for example, quotes from my quote journal or entries from a students diary) must be put to the test. Thus they are not adopted as the writers own, but in the process of testing them, the writer is cultivated/disciplined. To put this is Foucaults terms, the

The Cultivated Self: Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

373

writing of the hupomnemata is also (and must remain) a regular and deliberate practice of the disparate (Self Writing 212). The practice of the disparate is a way of combining the traditional authority of the already-said with the singularity of the truth that is affirmed therein and the particularity of the circumstances that determine its use (Self Writing 212). In other words, writing becomes, again, a practice of meditation, but in this practice, the writer considers the selected passage as a maxim that may be true, suitable, and useful to a particular situationor not. To explain this a bit further, the purpose here in practicing the disparate is for mastery over the self, not through a conclusive and utterly naked revelation of self, as is so often argued about Montaignes work, but through the acquisition and assimilation of truth. This truth is in the logoi, the teaching of the teachers. And this truth, found in the already-said, as its been called, grants the writer access to the reality of this world (Foucault, Technologies 35). For example, Montaigne finds that in all of the interpretations that might occur in the art of language, there is not one universally true interpretation. However, this does not discourage him from the practice of the disparate, for while belying the possibility of clear, irrefutable meaning in the language-use of, say, lawyers and doctors, Montaigne quotes Seneca (that is, an example of the already-said, the teaching of the teachers): What is broken up into dust becomes confused (Of Experience 816). This is a precise example of the writer testing a maxims truth, suitability, and usefulness in a particular context: In ultimately arguing that there is no one interpretation for a text, Montaigne finds Senecas statement to be true, suitable, and useful to his point. Also, by bringing together his experience and Senecas insight (by practicing the disparate), Montaigne gains access to reality, in this case the reality that when we take a closer look at the meaning-word relation, the equal sign we might assume (or hope) to be between them is simply not there. Would it not be wonderful if our students always approached outside sources the same way? Instead of inserting quotes that have been taken totally out of context, reduced to isolated entities, and thrust among the students own text like fence posts, they might actually test out the truth, the validity, of some piece of scholarship. They might meditate on it, even try to apply it to some situation in their own lives; they might attend to it seriously and see what comes out of that attending. I, for one, would much rather read those papers/essays than the ones where students write what they already think they know while simultaneously practicing reduction or outright misrepresentation of others works. After all, how much generation of knowledge, shared discovery, or intellectual exchange are we going to see in papers that do not practice any genuine attentiveness to othersother writers, other ideas, and so forth?

374

Rhetoric Review

The Process of Unification That said, the writing practices described here are not simply all about others. They are as much about the subject-that-is-the-writer per the relation that they enact between that subject and the subject that is constituted on the page. To put this in Foucaults terms, the role of writing is to constitute, along with all that reading has constituted, a body. That body is constituted because the writing becomes a principle of rational action in the writer himself. Per this principle, the writer constitutes his own identity through this recollection of things said (Self Writing 213). And in this way, the writer unifies all of these fragmentsthe fragments found in his or her hupomnemataby bringing them together, meditating on them, and, thereby, constituting a self. In other words, the writer constitutes his own identity by historicizing his or her self. Foucault states, Through the interplay of selected readings and assimilative writing, one should be able to form an identity through which a whole spiritual genealogy can be read (Self Writing 214). The writer negotiates his or her self within the discourses of truth that are at work, via the reading, rereading, meditating, and writing of, or on, other authors works. To put this in very practical terms, he or she enters into the conversation, as so many of my colleagues call it, a conversation that may be between the work of Montaigne and Foucault, for example. In practicing the disparate, there is awareness of that conversationthe writer becomes aware of what ideas/beliefs he or she is engaged with/in. He or she becomes aware of being a part of a lineage of ideas, of a system of beliefs, and so forth. Thus an essay is not the transparent representation of an isolated, fixed, stable, unique agent, nor is he or she the socially constructed representation of a pre-existing agent in a world that consists of re/oppressing practices. Rather, the self is an historical moment, an event in the movement of time, space, power, and so forth. Subjectivity in self writing and in an essay is possible because of (is produced by) the practices and processes articulated herereading, writing, practicing the disparate, and unification. To relay an apt metaphor, Seneca states, The voices of the individual singers are hidden; what we hear is the voices of all together. . . . I would have my mind of such a quality as this; it should be equipped with many arts, many precepts, and patterns of conduct taken from many epochs of history; but all should lend harmoniously into one (qtd. in Self Writing 214). What This Means for Debate In reference to classical texts, Foucault states, The care of the self is the care of the activity and not the care of the soul-as-substance (Technologies 25). In this statement lies the most profound distinction between the technologies

The Cultivated Self: Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

375

of self that are articulated by Foucault and arguably by Montaigne and the writing-of-self that is described in other versions of subjectivity: The self is not a substance. There is no given, fixed self, which is acted on and manipulated by outside forces, even by the outside presence/agency of the writer. Rather, in the act of writing (an act of caring), a self is constituted, and that act involves much more than the writer dictating what words make it onto the page, in what order, and in what context(s). Admittedly, this seeming reversal, where the subject is subjected, flies in the face of most Western philosophy. In an interview with Foucault, the interviewer states, But what I dont understand is the position of consciousness as object of an epistem. The consciousness, if anything, is epistemizing, not epistemizable. This confusion, perhaps, sums up the bewilderment toward Foucaults work on subjectivity, for most of Western philosophy operates under the fundamental belief that transcendental consciousness . . . conditions the formation of our knowledge (An Historian 98). Foucaults theory of subjectivity refuses an equation on the transcendental level between subject and thinking I. He states, I am convinced that there exist, if not exactly structures, then at least rules for the functioning of knowledge which have arisen in the course of history and within which can be located the various subjects (An Historian 98). For example, within the hupomnemata there are specific ruleslike the reading and recording of other authors texts, like the incorporation of them into the writers work, and so onthat serve as particular operations within which the subject-on-the-page is constituted. Obviously, the writer practices these practices, but he is not the transcendent origin of these practices. Rather, the point is that in these practices, the self is possible. This shift in thinking about subjectivityabout how the self is constituted in practiceshas implications for how we exchange ideas, how we enter into conversations and participate in them, how we debate. For now, the belief in opinion-as-identity destroys the possibility of productive exchange. For example, I spoke recently with a friend about (his interpretation of) particular tenets of Methodism. In discussion we were able to draw out how homophobia gets off the ground, so to speak, in that belief system. We did this work together, with me asking pointed questions and him responding to them as honestly as he felt he could. When I asked why he continued to believe in a school of thought that required him to reject his gay daughter, he became very upset. In the end he argued that the belief system was more important to him, because it defined for him what counted as a good life and a good person, than anything else (including acceptance of his daughters lifestyle). This was his choice, his identity, and I had no right to challenge it. Of course, because the rejected person is someone I care for, I was angry at said friend for his unwillingness to continue the conversation, the debate, about his

376

Rhetoric Review

belief system, just as I was angry at the student who joked about raping women for his stubborn alignment with a dangerous belief system. And no doubt they were angry with me for challenging their beliefs. The problem, though, is not that anger entered into the debate. Rather, the problem is that in both caseswith my friend and with my studentthe challenge was read as an attack (once my questions moved away from what do you believe? or what are you trying to say here? to what are the implications of those beliefsfor you and for others?). In reading the challenge as an attack, the exchange of ideas was cut off. The debate never really got to be a debate because, for both my friend and my student, the conversation was a situation where his opinion-as-identity was on the line. Each felt the need to defend that opinion-as-identity at all costs, not to debate. If we took seriously, though, the idea that the subject is constituted in practices, in the practices of self-writing, for examplein the practices of meditating on others works/insights and on our ownthen we would be able to get past the belief in opinion-as-identity and to actually exchange ideas, share opinions, and even potentially cultivate better selves. By better, I mean that in that exchange, wed be able to participate in the generation of other possibilities, in critique, and even (sometimes) in the resolution of conflict (which I do not necessarily equate to consensus), not simply the back-and-forth articulation of what we already know/believe. In other words, we would be cultivating more fluid, dynamic selves, not finite selves. Crowley and Hawhee state, In ancient times, people used rhetoric to make decisions, resolve disputes, and to mediate public discussion of important issues. . . . [Too,] rhetoric helped people to choose the best course of action when they disagreed about important political, religious, or social issues (1). I believe that rhetoric can still help us to accomplish these ends, not by imposing a better moral order but by creating and/or discovering possibilities for engagement among and within individuals and groups. However, until conceptions of the self change, rhetoric will continue to be seen as mere spat and disagreement as destructiveby popular culture. Consequently, we will continue to experience the same disengagement (including polarization) in student papers, in our class discussions, and even in our personal discussions. We must begin to take seriously the idea that we can cultivate our selves, discipline our selves, that the identity is not comprised of opinions that are uniquely ones ownpossessed by an individual genius. We must begin to teach our students how to participate in the cultivation and transformation of their selves in writing. We must continue to work to disrupt the conception of and belief in opinion-as-identity, for if we do not, then debate will continue to be a he said, she said affair, not the rigorous exchange of ideas and transformation of self and community we see in ancient rhetoric.

The Cultivated Self: Self Writing, Subjectivity, and Debate

377

Notes

Thanks very much to RR readers Peter Elbow and Edward Schiappa for their careful readings, thoughtful comments, and support in the revision and publication of this article. 2 That said, my work meets with an interesting danger: Though I hope that in narrowing my focus to Montaignes essays, I might avoid generalizing the essay as a genre, or writing as a practice, and instead exercise the kind of specific attentiveness that is far better mastered by Foucault, I find resisting that move to generalize difficult, if not in some cases impossible. Despite this potential/ inevitable failure on my part, my purpose here is to provide a different conceptualization of subjectivity in writing, one that could prove to be another way of potentially engaging other writers/essayists work, perhaps by future scholars. 3 Consequently, the concept of the writer-as-agent is disrupted in Foucaults work, and as such, one implication is that this version of subjectivity takes seriously the idea that the writer is one subject being subjected by a number of forces (acting on the body, for example) and that the subject-on-thepage is necessarily something different. 4 Though perhaps obvious, its worth pointing out here that reconceptualizing essay-writing as a complex of practices subverts the idea of the inspired or innately talented essayist. If we writing teachers want to take seriously the idea that it can be taught, then this theory of subjectivity gives us a way to teach it as a complex of practices, as something other than an expressive art that the student writer is innately either good at or not. 5 Specifically, correspondence is addressed to a particular reader (usually a close friend) in an attempt to make the writer present to that reader so that the text can act as a (often ethical) guide for the reader. At least in terms of Montaignes work, the reader was more generally conceived, and his project involved more than writing to guide, though that certainly could have been part of his purpose. 6 This is not to say that Foucault does not take seriously the ownership of texts by their authors. For example, in What is an Author? his study of the author function does not involve any assumptions about the author-as-creator of the text or about the author manifested in the text. Rather, Foucault is most interested in the historical operations that are part of the author function, a function that does not invoke the privileging of an authors agency over/in a text but an enunciation of how the authors name provides a mode of existence, circulation, and functioning of certain discourses (211). For example, a text with the name Montaigne attached to it can be expected to be a prototype of the essay. It can be expected to be written in a meandering, contemplative mode, to quote many important, classical authors, to incorporate personal experiences, and to be relentlessly skeptical of its own claims. 7 The similarities here in Foucaults articulation of self writing and Montaignes description of being made by his book are very likely due, at least in part, to the fact that Montaigne was such an avid reader of Senecas worka writer who was very much invested in the self-disciplining practices in self writing. Montaigne goes so far as to write about the Seneca in [him] in his essay Of Books (297), and in the same essay, he states that the books from which he learned to arrange [his] humors and [his] ways are those of Plutarch and Seneca. (It is worth noting, too, that in the 2003 Penguin Edition of Montaignes essays, translator M. A. Screech uses the verb control instead of arrange. See Michel de Montaigne: The Complete Essays. Translated and edited with an Introduction and Notes by M. A. Screech. As Foucault points out, [T]he theme of application of oneself to oneself is well known [in Antiquity]: it is to this activity . . . that a man must devote himself, to the exclusion of other occupations (Care 46). Montaigne, too, takes this occupation as seriously as the writers of Antiquity. He states, For those who go over themselves in their minds and occasionally in speech do not penetrate

1

378

Rhetoric Review

to essentials in their examination as does a man who makes that his study, his work, and his trade, who binds himself to keep an enduring account, with all his faith, with all his strength (Of Giving 504). 8 I believe that this is a reference to a metaphor about beehives found in the opening paragraph of Nietzsches Genealogy of Morals, and this metaphor, perhaps unsurprisingly, also shows up in Senecas writing. 9 In On Keeping a Notebook, Didion argues that we should use our notebooks to keep in touch with old selves, past experiences, seemingly fleeting ideas/images/feelings. She states, It is a good idea, then, to keep in touch, and I suppose that keeping in touch is what notebooks are all about (140).

Works Cited

Crowley, Sharon, and Debra Hawhee. Ancient Rhetorics: for Contemporary Students. 4th ed. New York, NY: Pearson/Longman, 2009. Didion, Joan. On Keeping a Notebook. Slouching Toward Bethlehem. New York, NY: Noonday P, 1968. 13141. Foucault, Michel. Care of the Self: Vol. 3 of History of Sexuality. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York, NY: Vintage, 1988. . An Historian of Culture. Foucault Live: Interviews, 19611984. Ed. Sylvere Lotringer. Trans. Lysa Hochroth and John Johnston. New York, NY: Semiotext(e), 1989. 95104. . Self Writing. Ethics, Subjectivity and Truth: The Essential Works of Michel Foucault, 19541984. Vol. 1. Ed. Paul Rabinow. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York, NY: New P, 1997. 20722. . Technologies of the Self. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Ed. L. H. Martin, H. Gutman, and P. H. Hutton. Amhurst: U of Massachusetts P, 1988. 1649. . What is an Author? Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology: The Essential Works of Michel Foucault, 19541984. Vol. 2. Ed. James D. Faubion. Trans. Robert Hurley and Others. New York, NY: New P, 1998. 20522. Greene, Liz, and Juliet Sharman-Burke. The Mythic Tarot. Chagrin Falls, OH: Fireside, 1986. Montaigne. Of Books. The Complete Essays of Montaigne. Trans. Donald M. Frame. Stanford: UP, 1958. 296305. . Of Experience. From The Complete Essays of Montaigne. 81557. . Of Giving the Lie. From The Complete Essays of Montaigne. 50306. . Of Presumption. From The Complete Essays of Montaigne. 478502. Muckelbauer, John. Imitation and Invention in Antiquity: An Historical-Theoretical Revision. Rhetorica 21.2 (2003): 6188. Rabinow, Paul. Introduction: The History of Systems of Thought. Ethics, Subjectivity and Truth: The Essential Works of Michel Foucault, 19541984. Ed. Paul Rabinow. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York, NY: New P, 1997. xixlii.

Sarah Allen is an assistant professor of English at the University of Northern Colorado. She teaches courses in rhetoric, composition theory, and creative nonfiction. She is currently working on a book on imitation practices in writing.

Copyright of Rhetoric Review is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- (O'Connor, Brian) Idleness A Philosophical EssDocument105 pagini(O'Connor, Brian) Idleness A Philosophical EssKaram Abu SehlyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Call of Character: Living a Life Worth LivingDe la EverandThe Call of Character: Living a Life Worth LivingEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (2)

- Contemporary Philosophy: The Promise of Philosophy and The Landmark ForumDocument9 paginiContemporary Philosophy: The Promise of Philosophy and The Landmark ForumTim20C100% (2)

- The Philosophy of UnschoolingDocument102 paginiThe Philosophy of Unschoolingxoxom19116100% (1)

- Love of KnowledgeDocument31 paginiLove of KnowledgeJOHNATIEL100% (1)

- CARET Programme1 Bennett-1Document10 paginiCARET Programme1 Bennett-1TerraVault100% (3)

- (Critical Perspectives) Paulo Freire-Pedagogy of Freedom - Ethics, Democracy, and Civic Courage - Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (2000) PDFDocument109 pagini(Critical Perspectives) Paulo Freire-Pedagogy of Freedom - Ethics, Democracy, and Civic Courage - Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (2000) PDFDavid VillegasÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Paul Lederach The Moral Imagination-Chapter 8Document217 paginiJohn Paul Lederach The Moral Imagination-Chapter 8Alexis Colmenares100% (2)

- Getting Queer:: Teacher Education, Gender Studies, and The Cross-Disciplinary Quest For Queer PedagogiesDocument24 paginiGetting Queer:: Teacher Education, Gender Studies, and The Cross-Disciplinary Quest For Queer PedagogiesKender ZonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychology, Power and PersonhoodDocument314 paginiPsychology, Power and Personhoodkoritzas100% (4)

- Application Performance Management Advanced For Saas Flyer PDFDocument7 paginiApplication Performance Management Advanced For Saas Flyer PDFIrshad KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- More Than Cool ReasonDocument12 paginiMore Than Cool Reasonisiplaya2013Încă nu există evaluări

- John Paul Lederach The Moral Imagination The Art and Soul of Building PeaceDocument217 paginiJohn Paul Lederach The Moral Imagination The Art and Soul of Building PeaceMarta Gomes100% (2)

- Borrero Anthony - Statement of Teaching Philosophy Spring 2013Document5 paginiBorrero Anthony - Statement of Teaching Philosophy Spring 2013api-216013501Încă nu există evaluări

- Fences - Physical and Socio-Cultural BoundariesDocument20 paginiFences - Physical and Socio-Cultural BoundariesvaidehiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Farr - 'Protest Genres and The Pragmatics of Dissent'Document9 paginiFarr - 'Protest Genres and The Pragmatics of Dissent'Kam Ho M. Wong100% (1)

- Phillips (2006) - Rhetorical Maneuvers - Subjectivity, Power, and ResistanceDocument24 paginiPhillips (2006) - Rhetorical Maneuvers - Subjectivity, Power, and ResistanceMichael JohnsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Download Complicities A Theory For Subjectivity In The Psychological Humanities Natasha Distiller full chapterDocument67 paginiDownload Complicities A Theory For Subjectivity In The Psychological Humanities Natasha Distiller full chapterrichard.talbott508Încă nu există evaluări

- Britzman-Is-there - a-Queer-Pedagogy-Or-Stop-Reading-StraightDocument17 paginiBritzman-Is-there - a-Queer-Pedagogy-Or-Stop-Reading-StraightChris AthertonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allsup - Creating An Educational Framework For Popular Music in Public Schools. Anticipating The Second-WaveDocument28 paginiAllsup - Creating An Educational Framework For Popular Music in Public Schools. Anticipating The Second-WaveemschrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self and SchizophreniaDocument21 paginiSelf and SchizophreniaAriel PollakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personal Experience Essay SamplesDocument5 paginiPersonal Experience Essay Sampleshixldknbf100% (2)

- Fan Shen The Classroom and Wider Culture Identity As A Key To Writing English CompositionDocument9 paginiFan Shen The Classroom and Wider Culture Identity As A Key To Writing English Compositionapi-239908663Încă nu există evaluări

- A Philosophical Retrospective: Facts, Values, and Jewish IdentityDe la EverandA Philosophical Retrospective: Facts, Values, and Jewish IdentityÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Quest For A New EducationDocument17 paginiThe Quest For A New EducationremipedsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foucault QuotesDocument3 paginiFoucault QuotesRaloÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Beginning To Irony - Self-Reflection in The Arts and SciencesDocument10 paginiFrom Beginning To Irony - Self-Reflection in The Arts and SciencesQ JoniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Royster - First VoiceDocument13 paginiRoyster - First VoiceИя ВласоваÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bolis&Schilbach Topo D 18 00007 r1Document52 paginiBolis&Schilbach Topo D 18 00007 r1Graziana RussoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Download Feeling Like It A Theory Of Inclination And Will Tamar Schaprio full chapterDocument67 paginiDownload Feeling Like It A Theory Of Inclination And Will Tamar Schaprio full chapteralfred.jessie484100% (5)

- Sentence Starters For Argumentative EssaysDocument5 paginiSentence Starters For Argumentative Essaysafibxejjrfebwg100% (2)

- Understanding Your Self in Various Perspectives (38 charactersDocument24 paginiUnderstanding Your Self in Various Perspectives (38 charactersLoad StarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Putting Emotion Into The Self: A Response To The 2008 Journal of Moral Education Special Issue On Moral FunctioningDocument23 paginiPutting Emotion Into The Self: A Response To The 2008 Journal of Moral Education Special Issue On Moral FunctioningMohamadFikrieIzuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hawthorne Reparative ReadingDocument7 paginiHawthorne Reparative ReadingSun PraboonyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ricoeur - Approaching The Human PersonDocument10 paginiRicoeur - Approaching The Human Personlucas StamfordÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Identify Themes in A Literature ReviewDocument5 paginiHow To Identify Themes in A Literature Reviewgahezopizez2100% (1)

- The Para-Academic Handbook: A Toolkit for Making-Learning-Creating-ActingDe la EverandThe Para-Academic Handbook: A Toolkit for Making-Learning-Creating-ActingAlex WardropÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cavell, The Division of TalentDocument20 paginiCavell, The Division of TalentMaria Nathalia SegtovichÎncă nu există evaluări

- Major Assignment 3 RemediatedDocument6 paginiMajor Assignment 3 Remediatedapi-708320736Încă nu există evaluări

- Anti War EssayDocument7 paginiAnti War Essayafibalokykediq100% (1)

- Kyle Bjorem's Philosophy of Teaching WritingDocument1 paginăKyle Bjorem's Philosophy of Teaching WritingNicholas SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nelsonturner ThecreativetheoryDocument8 paginiNelsonturner Thecreativetheoryapi-284708289Încă nu există evaluări

- Identity, GeeDocument28 paginiIdentity, Geeanon_421547066Încă nu există evaluări

- Excerpts On Spiritual & Psychological Effects of The OutdoorsDocument42 paginiExcerpts On Spiritual & Psychological Effects of The OutdoorsraywoodÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Aristotelian Primer On Making The Wrong Decision: IndecisitivityDocument17 paginiAn Aristotelian Primer On Making The Wrong Decision: IndecisitivityC.J. SentellÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Ethics, Diversity, and Conflict: The Graduate Years and Beyond, Vol. IDe la EverandOn Ethics, Diversity, and Conflict: The Graduate Years and Beyond, Vol. IÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Values. An Interview With Joseph RazDocument15 paginiOn Values. An Interview With Joseph Razramón adrián ponce testinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- TPM Philosophy Academic Philosophy and p4cDocument6 paginiTPM Philosophy Academic Philosophy and p4cGupi PalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Someone To Write My EssayDocument4 paginiSomeone To Write My Essaynpvvuzbaf100% (2)

- The Legacies of Liberalism and Oppressive Relations: Facing A Dilemma For The Subject of Moral EducationDocument21 paginiThe Legacies of Liberalism and Oppressive Relations: Facing A Dilemma For The Subject of Moral EducationColton McKeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Co-Subjective Consciousness Forms CollectivesDocument24 paginiCo-Subjective Consciousness Forms CollectivesfenomenotextesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Descombes A Propos of The Critique of The Subject (1988)Document9 paginiDescombes A Propos of The Critique of The Subject (1988)Boudzi_Boudzo_5264Încă nu există evaluări

- The Philosophy of Objectivism: Implications For Instructional DesignDocument12 paginiThe Philosophy of Objectivism: Implications For Instructional Designsam nacionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Real-Self Expression Exploring the Dimensionalities of Who We Are From the Authors of Letting Go and Taking the Chance to be RealDe la EverandReal-Self Expression Exploring the Dimensionalities of Who We Are From the Authors of Letting Go and Taking the Chance to be RealÎncă nu există evaluări

- LINDE - 1993 - The Creation of Coherence. Charlotte Linde, 1993.Document18 paginiLINDE - 1993 - The Creation of Coherence. Charlotte Linde, 1993.mecarvalhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflective Writing in ArtsDocument10 paginiReflective Writing in Artsfaizan iqbalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feminism NegDocument139 paginiFeminism NegPirzada AhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhetorical Analysis: University of Sulaymaniah College of Language School of EnglishDocument9 paginiRhetorical Analysis: University of Sulaymaniah College of Language School of EnglishAhmad HashimÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Axiomatic Self: A coherent architecture for modeling realityDe la EverandThe Axiomatic Self: A coherent architecture for modeling realityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding PDFDocument15 paginiUnderstanding PDFJerome Chester GayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Animal of realities: Our evolutionary identity as a species and individualsDe la EverandAnimal of realities: Our evolutionary identity as a species and individualsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Experiential Learning in Adult Education: A Comparative Framework by Tara J. Fenwick, Asst. ProfessorDocument20 paginiExperiential Learning in Adult Education: A Comparative Framework by Tara J. Fenwick, Asst. ProfessordinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Driscoll, Connected, Disconnected, or UncertainDocument24 paginiDriscoll, Connected, Disconnected, or Uncertainsem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Ching, Kory Lawson - Peer Response in The Composition Classroom - An Alternative GenealogyDocument18 paginiChing, Kory Lawson - Peer Response in The Composition Classroom - An Alternative Genealogysem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Carillo, Ellen - (Re) Figuring Composition Through Stylistic StudyDocument17 paginiCarillo, Ellen - (Re) Figuring Composition Through Stylistic Studysem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Bizup, Joseph - BEAM - A Rhetorical Vocabulary For Teaching Research-Based WritingDocument16 paginiBizup, Joseph - BEAM - A Rhetorical Vocabulary For Teaching Research-Based Writingsem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Teacher's Role in Enabling Students to Participate in Academic DiscourseDocument13 paginiTeacher's Role in Enabling Students to Participate in Academic Discoursesem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Borg, Erik - Discourse CommunityDocument3 paginiBorg, Erik - Discourse Communitysem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Fernsten, Linda - Discourse & DifferenceDocument18 paginiFernsten, Linda - Discourse & Differencesem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Bazerman, Charles - Discursively Structured ActivitiesDocument14 paginiBazerman, Charles - Discursively Structured Activitiessem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Biology Sample Paper Hacker John CSE BioDocument5 paginiBiology Sample Paper Hacker John CSE Biosem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Bisaillon, Jocelyne - Professional Editing Strategies Used by Six EditorsDocument28 paginiBisaillon, Jocelyne - Professional Editing Strategies Used by Six Editorssem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Over 100 Ways to Say "SaidDocument1 paginăOver 100 Ways to Say "Saidsem2u2Încă nu există evaluări

- Plo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentDocument22 paginiPlo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentkrystelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lifting Plan FormatDocument2 paginiLifting Plan FormatmdmuzafferazamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Derivatives 17 Session1to4Document209 paginiDerivatives 17 Session1to4anon_297958811Încă nu există evaluări

- Das MarterkapitalDocument22 paginiDas MarterkapitalMatthew Shen GoodmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- SyllabusDocument8 paginiSyllabusrickyangnwÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biomass Characterization Course Provides Overview of Biomass Energy SourcesDocument9 paginiBiomass Characterization Course Provides Overview of Biomass Energy SourcesAna Elisa AchilesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Container sizes: 20', 40' dimensions and specificationsDocument3 paginiContainer sizes: 20', 40' dimensions and specificationsStylefasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseDocument29 paginiInflammatory Bowel Diseasepriya madhooliÎncă nu există evaluări

- School of Architecture, Building and Design Foundation in Natural Build EnvironmentDocument33 paginiSchool of Architecture, Building and Design Foundation in Natural Build Environmentapi-291031287Încă nu există evaluări

- Readers TheatreDocument7 paginiReaders TheatreLIDYAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arcmap and PythonDocument29 paginiArcmap and PythonMiguel AngelÎncă nu există evaluări

- ILOILO Grade IV Non MajorsDocument17 paginiILOILO Grade IV Non MajorsNelyn LosteÎncă nu există evaluări

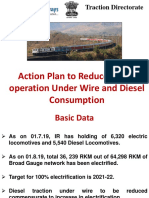

- Final DSL Under Wire - FinalDocument44 paginiFinal DSL Under Wire - Finalelect trsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bhikkhuni Patimokkha Fourth Edition - Pali and English - UTBSI Ordination Bodhgaya Nov 2022 (E-Book Version)Document154 paginiBhikkhuni Patimokkha Fourth Edition - Pali and English - UTBSI Ordination Bodhgaya Nov 2022 (E-Book Version)Ven. Tathālokā TherīÎncă nu există evaluări

- It ThesisDocument59 paginiIt Thesisroneldayo62100% (2)

- Legend of The Galactic Heroes, Vol. 10 Sunset by Yoshiki Tanaka (Tanaka, Yoshiki)Document245 paginiLegend of The Galactic Heroes, Vol. 10 Sunset by Yoshiki Tanaka (Tanaka, Yoshiki)StafarneÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV Finance GraduateDocument3 paginiCV Finance GraduateKhalid SalimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab 5: Conditional probability and contingency tablesDocument6 paginiLab 5: Conditional probability and contingency tablesmlunguÎncă nu există evaluări

- MES - Project Orientation For Night Study - V4Document41 paginiMES - Project Orientation For Night Study - V4Andi YusmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henry VII Student NotesDocument26 paginiHenry VII Student Notesapi-286559228Încă nu există evaluări

- Cover Letter IkhwanDocument2 paginiCover Letter IkhwanIkhwan MazlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lcolegario Chapter 5Document15 paginiLcolegario Chapter 5Leezl Campoamor OlegarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- CERTIFICATE - Guest Speaker and ParentsDocument4 paginiCERTIFICATE - Guest Speaker and ParentsSheryll Eliezer S.PantanosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managing a Patient with Pneumonia and SepsisDocument15 paginiManaging a Patient with Pneumonia and SepsisGareth McKnight100% (2)

- Verbos Regulares e IrregularesDocument8 paginiVerbos Regulares e IrregularesJerson DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iso 30302 2022Document13 paginiIso 30302 2022Amr Mohamed ElbhrawyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Simptww S-1105Document3 paginiSimptww S-1105Vijay RajaindranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kenneth L. Campbell - The History of Britain and IrelandDocument505 paginiKenneth L. Campbell - The History of Britain and IrelandKseniaÎncă nu există evaluări