Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Adekoya SexualityTermPaper Final

Încărcat de

ohayshayDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Adekoya SexualityTermPaper Final

Încărcat de

ohayshayDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Adekoya 1

Sewa Adekoya Sexuality Term Paper Clare Casey Favela On Blast: How Brazilian Baile Funk Inspired The World To Express Yourself The film, Favela on Blast, directed Wesley Pentz and Leonardo HBL, gives an introductory overview of the genre, culture, and lifestyle of funk a type of music that originated in the slums of Rio de Janeiro. While funk music in Brazil was born from imported records of American pop, soul, and funk singers, today funk has created its own distinct sound, which has evolved to represent the millions of poor people who populate the favelas (slums). While more popular funk songs of the 2000s were produced by male DJs and contained explicit, sexual and erotic content, female funkeiras (funk artist) have brought their own manner of sexual discourse to funk music, thus challenging and subverting the traditional roles of women in the favela. Filmmaker Wesley Pentz, also known as DJ Diplo, is famous for his eclectic mix of world rhythms and electric beats, drawing most of his inspiration from Brazil, Jamaica, and countries of the Caribbean. However, the sexual scripts, and definitions of gender and sexuality vary quite greatly between the United States and the Caribbean. Critics of Diplos music have argued that his interpretations and reenactments of third world cultures promotes a negative stereotype of men and women who inhabit the areas where his music originates from. Although both cultures have varying definitions of gender and sexuality, Diplos formal introduction of baile funk culture to the first world introduces a new opportunity for teenagers and young adults to claim, and quite literally express their own gender and

Adekoya 2

sexuality. Nevertheless, this call for sexual liberation would have never occurred if it wasnt for the cultural phenomenon of baile funk and funk music in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Funk carioca (carioca is a demonym for inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro), or simply funk can trace its origins back to the 1970s. Club owners of the most popular venues for pop music in Rio de Janeiro would hold special funk themed nights, where DJs played rock, pop, and especially soul music by artists such as James Brown, Wilson Pickett, and Kool & the Gang (Filho, Herschmann 226). As these funk nights gained incredible popularity, especially among residents of Rio de Janeiros favelas (called favelados), these dances moved from the restricted space of the night club to larger, outdoor venues hidden among within the favelas. Whereas funk nights at clubs could attract over 5,000 guests at one time, bailes in the favelas could draw over 10,000 guests and last virtually from sundown to sunrise. During the 1980s, funk began to evolve from purely American soul and funk music to a form uniquely Brazilian what we refer to as funk carioca today. Early funk carioca DJs became interested in Miami Bass, an electro-funk variant of hip-hop made popular by Afrika Bambataa. Using records brought overseas by DJs who could afford to travel between Miami and Rio de Janeiro, funk DJs combined these new electronicsynth sounds and beats, with traditional Afro-Brazilian rhythms, and samples from the same American soul records popular during the 1970s to create the heavy, pulsing bassline that so distinctly defines funk carioca as its own genre. Even 30 years after the birth of funk carioca, the style remains largely the same: Theyve stopped making [American funk], but we still add our own flavor, Brazilian groove (DJ Grandmaster

Adekoya 3

Rafael, Favela on Blast). But what defines this distinct flavor; this Brazilian groove that makes funk so unique and exciting? While the DJs were responsible for creating funks sound, it was the MCs who brought their own distinct style and flavor to funk. During the late 1980s, MCs would simply translate the lyrics of a funk-remixed Miami Bass or Hip-Hop song into Portuguese, so that baile attendees would understand the lyrics. However, MCs were not allowed to create and practice their own individual style whilst under the constraints of simply translating English lyrics. Instead, MCs saw funk as a means to share their stories, and voice the realities of a lifestyle they knew best life in the favela. Before, funk was like samba, the slum singing to the rest of the city, telling them about their issues. After, it became the slum singing for the slum (DJ Marboro, The Funk Phenomenon). Sometimes declared formally as funk do bem (good funk), these songs tell the real tale of life in the ghetto lyrics about violence, the government, young love, and longing for peace are popular among lyricists. Funk is the music of Rio de Janeiros favelas its not just a sound, but it is a phenomenon that can only be completely understood by the favelado, someone born and bred in any one of the citys more than 600 slums. While the first MCs of funk wrote anthems charged with a sociopolitical agenda, MCs of the 2000s ventured into new themes and topics, creating a number of subgenres that have garnered international attention. Perhaps given the most attention from both national and international media sources, proibido funk (prohibited funk) is a subgenre known for its close ties with the gangs of Rios favelas. Lyrics are usually about armed violence, drugs, and women; its common to hear the artist give a shout out to a specific gang, as drug lords and gang

Adekoya 4

leaders most often always are the people who fund and produce proibido songs. By the mid-2000s, many new funk MCs began to produce songs with a more explicit message a trend that led to the birth of the subgenre, funk ertico (erotic funk). While other names of the subgenre include putaria funk or funk sensual, the subgenre is best defined by its tendency to include extremely sexual content. The song, Me Chupa, by MCs Gorilla & Preto is one example of a typical funk ertico. In the lyrics, the male MC demands for his female partner to perform oral sex simultaneously ordering her to do so without dribbling on him. Me Chupa MC Gorilla e Preto Chupa-pa, no me baba! No me baba! No me baba! Estava doida pra la vce entao entao, E a, chupa ma, no me baba! No me baba! Suck it up but dont dribble! Dont you dribble! Dont you dribble! She was crazy for you then, so therefore, Suck it up, but dont dribble! Dont dribble on me!

Today, funk erotica songs similar to Me Chupa dominate the playlists of the bailes. However, the sentiments expressed through the lyrics of funk ertico have translated to literally embody many physical aspects that define funk culture, and its most important tradition the baile. In Favela on Blast, we visit a number of different bailes in Rio de Janeiro. Scenes primarily consisted of young girls dressed in tight, lowcut tops and short skirts, all proudly bearing their midriffs as they suggestively sway (or shake) to the beat of the infamous funk bassline. At times, male MCs will select a girl from the crowd and invite her to join him onstage; an invitation that usually leads to the pair dancing suggestively with each other, or pretending to reenact a sexual act. At first, funk erotica songs seem to exist purely for entertainment; lyrics tend to be humorous or satirical, full of sexual metaphors and double meanings that frolic along

Adekoya 5

the heavy drum of the funk bass. However, a further investigation of sexual roles and scripts within the favela reveals an interesting perspective of how gender and sexuality is defined among favelados, and played out on stage through funk erotica. In Brazilian society, gender is defined by much more than ones physical genitalia. In his book, Bodies, Pleasures, and Passions, Richard Parker defines gender in Brazilian society as the following: Definitions of macho (male) and fmea (female), conceptions of masculinidade (masculinity) and feminidade (femininity), notions of what it is to be an homem (man) as opposed to a mulher (woman) in Brazilian society, and understandings of the ways in which such notions shape ones sexual experience in contemporary Brazilian life (34). Parker theorizes that definitions of contemporary gender roles in Brazil are rooted in the countrys colonial past the social and gender order established by the patriarchal slave owner allowed for his own sexual freedom. During this time, it was not uncommon for a slave owner to father a number of children with female slaves outside of his nuclear marriage. Today, favelados continue this patriarchal tradition, as gender roles and scripts still allow for such transgressions to occur with little to no consequence. As the active male is understood to inhabit a natural, animal-like desire for sex, the passive female is praised for her virginity and delicacy. Funk songs more than encourage these preconceived definitions of gender, as lyrics have begun to drift away from romantic ballads about walks on the beach, to angry and violent demands for women to have sex with the MC. Though male MCs have long dominated the entire genre of funk, the growing

Adekoya 6

popularity of funk ertica during the 2000s inspired a number of women to pick up the mic and become MCs themselves. Just like their male counterparts, female MCs tend to write sexually explicit lyrics in line with funk ertica. Yet funkeiras have created their own subgenre of funk ertica funk fmea, a medium of expression that challenges the traditional definitions of gender roles and sexual scripts within the favela. Sexuality is a key metaphor used by Cariocas in their everyday language and description of almost all aspects of social life (Goldstein, 228). Sexual metaphors, or words with sexual double meanings are quite popular, and commonly used in casual, daily discussions. Richard Parker clues that the Brazilian concept of sacanagem may explain why people are so comfortable with discussing sexual content with one another: Whether used positively or negatively, whether referring to injustice or violence, to joking, to teasing, to obscenities or sexual innuendos, to pornographic or erotic materials, or to specific sexual practices themselves, sacanagem focuses on breaking the rules of proper decorum - the rules that ought to control the flow of daily life (117). For women in the favelas, sexual teasing and playful banter among one another carries the discussion of sexual culture. The use of joking and teasing to aid sexual discussions permeates everyday relations and allow[s] for commentaries that might be more difficult to speak about directly. As demonstrated in funk fmea, [b]eing clever with words and stories has value, as does the ability to respond appropriately to a joke (Goldstein, 230). Through this vocal subversion of gender and sexuality, it is the woman who becomes empowered, as she now assumes the position of the active partner, forcing her male partner to sit down, shut up, and listen to exactly what she has to say.

Adekoya 7

In Favela On Blast, we meet one of the most popular women in funk, Deise Tigrona. Known for her use of words with double meanings in her lyrics, Tigrona was one of the first female MCs to produce explicit funk ertica, including one of the first funk songs that explicitly described sex positions within its lyrics. Tigrona is also responsible for writing arguably the most well-known funk ertica song to date: Injeo (Injection). Tigrona maintains that the song describes a visit to the doctor when the doctor tells Tigrona that she needs an injection, she loudly protests, declaring Ai! Doutor que dor!/Ai, medico que dor! (Ow! Doctor that hurts!/Ow, medic that hurts!). Nevertheless, a second reading of the songs lyrics suggests a more erotic encounter, as the term injeo is slang for penis. Other lyrics suggest that her cries of protest are simply because he is having anal sex with Tigrona, to which she clearly doesnt enjoy. Although Tigrona was quite popular in Brazil before the release of Injeo, she gained international success after the director, under his stage name of Diplo used a sample from Injeo for the remix of British rapper M.I.A.s song Bucky Done Gone. In many ways, M.I.A. (whose real name is Maya Arulpragasam) is similar to Deise Tigrona: the rapper complements her electronic/hip-hop beats with lyrics that range in topic from gender and sexuality, to politics and revolution. Thus, Diplos fusion of M.I.A.s political message and Deise Tigronas demanding, electric melody only seems like common sense. After the songs release in 2004 on the Diplo-produced M.I.A. mixtape, Piracy Funds Terrorism, Diplo, M.I.A. and Deise Tigrona achieved global stardom virtually overnight. Diplo, known for his unique affinity for world rhythms and electronic beats, has continued to produce hundreds of funk-inspired songs for some of the most popular

Adekoya 8

singers, rappers, and entertainers in the world. As of recent, Diplo has become more invested in Jamaican dancehall, than Brazilian funk but in many ways, the two genres are exactly the same, just from different origins. His exploration into Jamaican dancehall is evidenced through his project Major Lazer, one of the most popular acts in the world of Electronic & Dance Music (EDM). Despite his international success, some have criticized the producer of stealing tropical cultures and re-appropriating them for his own monetary benefit. Others have labeled Diplo misogynist and a racist, as the album cover of his hit song, Express Yourself, released in 2012, featured a picture of a black girl standing upside-down on her hands, with her feet spread wide and her butt out. The music video pushed things even further, as it almost entirely consists of black women expressing themselves, or rather, vigorously shaking their butts while in this upside-down position. A huge viral success, the video thus inspired girls around the world to try and express themselves: the Twitter trending topic #ExpressYourself produces thousands of pictures of girls expressing themselves in front of cop cars, in the middle of lecture halls, on bails of hay in the middle of a corn field, and virtually any other situation you can think of. At concerts, the DJ is known to invite girls from the audience to express themselves on stage, alongside his team of Caribbean dancers. Diplo defends the trend, arguing that expressing yourself derives from a popular Jamaican dance style called daggering, and is not too far off from other Caribbean dance styles, from Brazil to Jamaica, and everywhere in-between. Were just trying to document what it is we like about Jamaican music and culture. There is so much talent, not just in the music but [also] in the

Adekoya 9

dancing and the whole style and fashion there. We just wanted to incorporate everything we love about Jamaican culture and music. Not a lot of record labels support the wealth of talent that is in Jamaica, so we wanted to do something that would bring it attention (Wesley Pentz, Major Lazer: Does Switch and Diplos new side project exploit Jamaicans?) Contrary to the arguments of his critics, Diplo believes that the act of expressing yourself encourages women to step out from the restrictions of traditional gender roles and definitions, and openly own their sexuality. While the song itself doesnt contain any especially sexual or erotic lyrics, the act associated wit the song is regarded as one of a gender deviant a woman who tries to assume the role of the active, rather than the passive partner. Sound familiar? Although funk ertico was completely revolutionized by funkeiras as a means of challenging the traditional gender hierarchy and definitions of sexuality and gender that were long assumed as popular belief within the favelas, American producer Diplo used the distinct edge to help propel the career of M.I.A., another female artist with a strong message to share with the world. Thanks to the success of his partnership with M.I.A., as inspired almost entirely by Brazilian funk music, Diplo has since established himself, and his music, as a means of discourse between entirely different cultures on topics of politics, music, dance, and finally, gender and sexuality.

Adekoya 10

Works Cited Duran, Jose D. "Major Lazer: Does Switch and Diplo's new side project exploit Jamaicans?" New Times Miami [Miami] 13 May 2010: n. pag. New Times Miami. Web. 22 Apr. 2013. <http://www.miaminewtimes.com/2010-05-13/music/majorlazer-does-switch-and-diplo-s-new-side-project-exploit-jamaicans/full/>. Filho, Joo Freire, and Micael Herschmann. "Funk Music Made in Brazil." Brazilian Popular Music and Citizenship. Ed. Christopher Dunn and Idelber Avelar. Durham: Duke UP, 2011. 234-50. Print. Goldstein, Donna M. Laughing Out Of Place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality in a Rio Shantytown. Ewing: U of Californa P, 2003. Print. Natal, Bruno. "The Funk Phenomenon." XLR8R 1 May 2005: n. pag. Web. 22 Apr. 2013. <http://www.xlr8r.com/features/2005/05/funk-phenomenon>. Parker, Richard G. Bodies, Pleasures, and Passions: Sexual Culture in Contemporary Brazil. 2nd ed. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 2009. Print. Pentz, Wesley, and Leandro HBL, dirs. Favela On Blast. Mad Decent, 2008. Film.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Diapositivas 13Document98 paginiDiapositivas 13Reyes AlirioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Space Dye VestDocument3 paginiSpace Dye VestDon YurikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Msza Święta Pieśni Wiara / SigismundusDocument4 paginiMsza Święta Pieśni Wiara / SigismundusMiłosz AleksandrowiczÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scarlatti CatalogoDocument100 paginiScarlatti Catalogoorlando_fraga_1Încă nu există evaluări

- Sanctus - SchubertDocument1 paginăSanctus - Schubertnestor martinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Octave - Quarter Tone Fingering Chart For SaxophoneDocument2 paginiFirst Octave - Quarter Tone Fingering Chart For SaxophoneAris DolceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Counting Stars Uke Tab by One Republic - Ukulele TabsDocument4 paginiCounting Stars Uke Tab by One Republic - Ukulele Tabsjl75brÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dyslexic Reader 2007 - Issue 46Document32 paginiThe Dyslexic Reader 2007 - Issue 46Davis Dyslexia Association International100% (3)

- Scarborough Fair Simon and GarfunkleDocument2 paginiScarborough Fair Simon and GarfunkleDick FletcherÎncă nu există evaluări

- MR Brightside Song BreakdownDocument4 paginiMR Brightside Song BreakdownSteven SwiftÎncă nu există evaluări

- CSIM RTI SJorda03 InteractiveMusic LowRes PDFDocument32 paginiCSIM RTI SJorda03 InteractiveMusic LowRes PDFStefano FranceschiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Independent Research Project ProposalDocument2 paginiIndependent Research Project Proposalapi-425744426Încă nu există evaluări

- Situs Inversus (l9pl)Document71 paginiSitus Inversus (l9pl)Jack BlackburnÎncă nu există evaluări

- OverlandersDocument17 paginiOverlandersJoe FloodÎncă nu există evaluări

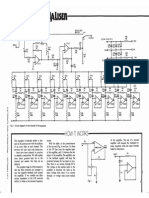

- 20 Band Equalizer - Graphic Equaliser 01Document3 pagini20 Band Equalizer - Graphic Equaliser 01vdăduicăÎncă nu există evaluări

- IHVH ADNI Lesson1Document3 paginiIHVH ADNI Lesson1Sagradah FamiliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Schumann Metrical DissonanceDocument305 paginiSchumann Metrical Dissonancerazvan123456100% (5)

- St. Louis Symphony Broadcast Program, May 4, 2013Document16 paginiSt. Louis Symphony Broadcast Program, May 4, 2013St. Louis Public RadioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approach Technique With Mechanical Voicings: ObjectiveDocument6 paginiApproach Technique With Mechanical Voicings: ObjectivekuaxarkÎncă nu există evaluări

- MusicDocument12 paginiMusicAliza Bombane100% (1)

- Under The SkinDocument6 paginiUnder The SkinevelynsilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Books Brunch 2019Document33 paginiBooks Brunch 2019api-293626321Încă nu există evaluări

- Coin Collecting Magazine January 2019 PDFDocument84 paginiCoin Collecting Magazine January 2019 PDFClaudius100% (3)

- Orientalism.: ExoticismDocument3 paginiOrientalism.: ExoticismwmsfÎncă nu există evaluări

- NSTP Script FinalDocument3 paginiNSTP Script FinalPablo EnriquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The History of The Philippines National Anthem and Flag: Lupang HinirangDocument2 paginiThe History of The Philippines National Anthem and Flag: Lupang HinirangEarlkenneth NavarroÎncă nu există evaluări

- UcmDocument2 paginiUcmgocoolonÎncă nu există evaluări

- LigetiDocument1 paginăLigetiCinemaQuestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toyota Prado Wiring 3rz-FeDocument45 paginiToyota Prado Wiring 3rz-FeaswitoNR88% (17)

- Zo Slater's Book of Short StoriesDocument51 paginiZo Slater's Book of Short StoriesZo Slater100% (1)