Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Hayles - Is Utopia Obsolete

Încărcat de

mzzionDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Hayles - Is Utopia Obsolete

Încărcat de

mzzionDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Peace Review 14:2 (2002), 133139

I s Utopia Obsolete?

N. Katherine Hayles

In Achieving Our Country, Richard Rorty observes that American contemporary novelists no longer take pride in the nation. Have artists and writers lost faith in our ability to make a better future? If so, what does this mean for envisioning a future we would want to inhabit? To explore these questions, consider Neal Stephensons The Diamond Age: or, A Young Ladys Illustrated Primer. In The Diamond Ages near-future world, nano-technology provides material abundance virtually without cost; the text explicitly states that some cultures work better than others and provides a blueprint of a successful one; and the narrative comes complete with a traveler who visits strange lands. Yet somehow, these elements do not cohere to make a utopia. Rather the narrative enacts what might more appropriately be called a mutopia, Istvan Csicsery-Ronays term alluding to the mutability of the postmodern condition that makes it so inimical to utopias. The mu of mutopia has another meaning as well. Mu is the Zen answer meaning neither yes or no, signifying an indeterminacy that indicates that the frame of the question is too narrow to encompass the answer. The narrow question is why A Diamond Age cannot coalesce into a utopia. The broader framework points toward a profound shift away from the idea of the autonomous individual, a cornerstone of Western democracy, toward more complex structures. Taking The Diamond Age as my example, I will argue that a mutopia both inscribes and implodes the utopian space. The conditions of utopia are present, but they are embedded in such complex contexts that the traditional separation between utopian and normal society cannot obtain. Without this buffer zone, complex feedback loops between utopian isolation and quotidian reality so complicate the utopian project that it can no longer be seen as utopian. Mutopia differs from utopia not primarily in its mutability (here I depart somewhat from Csicsery-Ronays formulation) but in its increased complexity and especially in the recursive loops connecting it to reality. Mutopia is the hybrid offspring of utopia and a reality too complex to t into utopian formulae. Kin to the intelligent machine and rst cousin to the cyborg, mutopia announces not just a new kind of social pact but also a mutation of the human into the posthuman.

n focusing on the tensions implicit in the construction of a mutopian space, I follow the lead of Louis Marin in his seminal book Utopics: Spatial Play and his article Frontiers of Utopia: Past and Present. Juxtaposing two views of the Sears Towerthe expansive, dominating view from the top and the restricted, dominated view from its baseMarin sees the frontiers of utopia formed through two contrary impulses:

ISSN 1040-265 9 print; ISSN 1469-9982 online/02/020133-0 7 DOI: 10.1080/1040265022014014 8 2002 Taylor & Francis Ltd

134

N. Katherine Hayles on the one hand, a free play of imagination in its inde nite expansion measured only by the desire, itself in nite, of happiness in a space where the moving frontiers of its philosophical and political ctions would be traced; on the other hand, the exactly closed totality rigorously coded by all the constraints and obligations of the law binding and closing a space with insuperable frontiers that would guarantee its harmonious functioning.

The dynamic can be gured spatially by juxtaposing the construction of the utopian frontiers from the inside out and from the outside in. From the inside, the space is constituted through the free play of imagination in contrast to the awed exterior. But to maintain itself as a boundary, the utopic space has to legislate differences that maintain its separateness from the outside, which leads to the exactly closed totality rigorously coded by all the constraints and obligations of the law. The boundary is not merely constituted through this paradoxical dynamic between freedom and constraint; rather, as Marin points out, the boundary is this dynamic. By contrast, in a mutopia the free play of imagination is not merely juxtaposed with the constraint of law but is put into a feedback loop with it. As a result, the two are joined into a single complex system indistinguishable any longer as inside and outside, and the boundary implodes, transforming the utopia into a mutopia. To see the formation and explosion of boundaries, consider two episodes. In one, the Bespoke Artifex John Percival Hackworth takes his wife Gwen and daughter Fiona on an expedition to celebrate the birthday of Princess Charlotte. In honor of the occasion, the Bespoke engineers have created smart coral, bio-computational devices programmed to form an island at just the right time for the birthday party, complete with fanciful fauna such as unicorns. Hackworth and his family watch the process through the crystalline diamond oor of the airship, itself a marvel of the nano-engineering that the island whimsically instantiates. As the converging smart coral creates turbulence, a few drops sprinkle on the airship, prompting hearty laughter from all of the fathers in the ballroom, who were delighted by the illusion of danger and the impotence of nature. This view, traditional in the belief that the fathers can dominate nature without changing their own nature, depends on being able to isolate acts of domination so they do not affect those who dominate. A few pages later we are presented with the trial and execution of Bud, a slacker and drug pusher who is Harvs and Nells father, although he has scarcely seen Harv and has not bothered to check if Nell, now three, has been born. Judge Fang, judging Bud worthless and of no account as a father, has no compunction about delivering his sentence. A few days later Bud is told to walk to the end of a funeral pier, whereupon nano-devices injected in his bloodstream explode and turn him into soup. The nanosite injection may appear to be simply a novel way to carry out capital punishment. But the convoluted plot soon makes clear that human skin no longer de nes an autonomous individual with the right to self-identity and self-possession. The boundary that served as the basis for liberal humanism, the belief that every person has the right to own themself and their own labor, is undercut as nanosites of every variety in ltrate lungs, infest bloodstreams and mix with semen while carrying out their own computational agendas as autonomous agents. To them the skin is a permeable boundary across

Is Utopia Obsolete?

135

which they communicate with other agents while remaining oblivious of human consciousness, which in turn is oblivious of them. Already destabilized by cartographic indeterminacy, utopian boundaries are further subverted by the dynamic interplay between large and very small. On a macroscale geography is one thing, and on a nanoscale another thing entirely. The (m)utopian boundary between inside and outside is constituted through the dynamic between the person who operates according to an imagined psychic wholeness, and nanosites that operate according to computational algorithms. The operations that would constitute the utopian borders are undone as soon as they are done, for a border on one scale is a permeable membrane on another.

he situation is further complicated by multiple recursive loops between levels. To trace them, let us consider the injection of nanosites, not into a lowlife like Bud, but rather into Hackworth. Hackworth permits the injections because he has fallen into the hands of Dr. X, to whom he went to make illegal copies of the A Young Ladys Illustrated Primer. He was commissioned to fabricate the Primer by none other than Lord Finkle-McGraw, equity lord and a ranking personage in the political hierarchy. The Neo-Victorian phyle to which FinkleMcGraw belongs, created as a utopist response to the moral relativism of the late twentieth century, represents a return to Victorian values and more fundamentally a return to the belief, as Finkle-McGraw says, that some kinds of behavior were bad and others good, and that it was reasonable to live ones life accordingly. As the Neo-Victorians prosper and solidify their tribal codes, largely through their technical superiority in nano-technology, the phyle grows in in uence and power. But Finkle-McGraw wants members of the phyle to adopt its creed through informed choice, not merely childhood indoctrination. To counteract the inevitable ossi cation that takes place as pioneers are succeeded by technocrats, he wants to encourage subversives, by which he means people who refuse to accept received dogma, preferring to work their ideas out for themselves. Con dent that this independence will convince the subversives that Neo-Victorian culture is indeed superior, he wants most of all to infect his granddaughter Elizabeth with subversion. To this end he commissions Hackworth to create A Young Ladys Illustrated Primer, designed as counter-indoctrination to the cultures prevailing norms. A marvel of sophisticated nanocomputing, the Primer can be thought of as itself utopian, for it represents a world so compelling that it seems to provide a bounded and secure alternative to the real world. Its utopian capabilities become especially obvious when it falls into the hands of Nell, with its heroic depictions of Princess Nell standing in stark contrast to her abusive environment. Yet Nell does not merely retreat to the Primer and choose to live there rather than in the real world. The very interactivity that gives the Primer its power over Nell connects her to the world through complex feedback loops. The Primer can sense its surroundings and constantly rearranges its narratives accordingly, creating highly interactive simulations that both mirror and transform the circumstances in which it is placed. The same kinds of recursive loops also operate at the macro level. Intrigued by the idea of the Primer, Hackworth decides to make a secret copy for his daughter Fiona, venturing into the Leased Territories, playground of Dr. X, to

136

N. Katherine Hayles

carry out the copying operation. But on his way homehaving transgressed the border that separates the af uent Neo-Victorian New Atlantis from the slums of the Leased Territorieshe is set upon by a gang of young thugs and loses the Primer. Complications from this incident bring him into the court of Judge Fang, who has become an associate of Dr. X. Hackworth is caned and receives a sentence of ten years, which he will end up spending with the Drummers, but not before Lord Finkle-McGraw turns him into a double agent. From Dr. X, Hackworth receives the injection of nanosites that will direct his actions among the Drummers, using the rod computers that infect their bloodstream to carry out a massive computational project to create the Seed, an alternative technology to the Feed that gives the Neo-Victorian phyle their political clout. Were the Seed to be completed, it would break the Neo-Victorian monopoly and dramatically alter the balance of power. This macroscale con ict is played out within Hackworths body as he receives from the Neo-Victorians another set of nanosites designed to surveille the rst set, so that his body becomes a contested terrain in which nanosite ghts with nanosite and purity is an optical illusion. If the Neo-Victorian phyle is one version of utopia, Hackworths body is another, for he exempli es the rational autonomous subject. After his nanosite infestation his body, like New Atlantis, becomes enmeshed in complex feedback loops that make it impossible to maintain the borders intact. Yet these very mutations are brought about precisely by the desire to maintain a utopian isolation, for which the New Atlanteans and the Celestial Kingdom both strive in different ways. As a result of these feedback loops, the utopian project fails at every level, from the socioeconomic to the cultural and psychological. Consider the Feed, a marvel of nano-engineering that creates unlimited pure water and energy by sorting molecules into the appropriate categories. The Feed in turn runs the matter compilers, machines that can create anything, from soup to mattresses, by manipulating atoms to form the desired structures. But this material abundance does not eliminate class, nor does it do away with child abuse. Nell can use the matter compiler to ll her room with mattresses for the stuffed toys that are her constant companions, but it does not prevent her mother from bringing home boyfriends who do everything from molest the little girl to torture her with cigarette burns. Technology alone, the text insists, cannot bring about constructive social change because it represents only one point of intervention in complex social dynamics. So deeply is this felt to be the case that, somewhat inexplicably, the narrative asserts that peasants in the Celestial Kingdom (a thinly veiled euphemism for China) are starving. Whether this is because the technology has not penetrated into remote rural regions, or because the mandarin ruling class has prohibited its introduction, the famine nevertheless reinforces the point that the technology by itself cannot create a utopia. Dr. X expands on the idea when he explains to Hackworth why he wants to create the Seed. When Western technology is introduced, Dr. X asserts, it carries along with it not only the yong of the technology but the ti of cultural values embedded in technologys structure and operation. The values the Feed instantiates are according to him entirely Western, based on hierarchical structures of control. The Seed, by contrast, would provide a different metaphor, one he

Is Utopia Obsolete?

137

believes more suited to Chinese traditions. Rather than a centralized hierarchy, the Seed would be distributed to humble agrarian workers who would use planting and harvesting techniques to make it produce goods, which they would then bring to market in distributed networks that emphasize local control and a peaceful order spreading from the bottom up rather than the top down. Here again we see the utopian impulse in play, as Dr. X envisions an adaptation of existing technology that would enable the Celestial Kingdom to break its reliance on Western technologies and reclaim its ancestral territory. This ambition takes shape through the Fists, a Boxer-like rebellion orchestrated by Dr. X and other mandarins to purge foreign devils from Celestial Kingdom soil. Yet this isolationist program, carried out in the name of utopian reform, is complicated when the Fists assault on Shanghai meets with erce resistance from the Mouse Army, adolescent Chinese girls who have been raised on bootleg copies of the Primer that Dr. X. has blackmailed Hackworth into creating. Presumably Hackworth altered the program so that the girls, instead of faithfully adhering to indigenous Chinese values, adopt as their Queen and heroine Nell, herself also raised by the Primer, although a different version. It remains a mystery why Nells Primer would educate her to be a self-reliant individual, whereas the Chinese girls are indoctrinated to form the massive Mouse Army whose main purpose in life is to rescue Nell. Nell plays the starring role as the quintessential freethinker and ultimate individual, whereas thousands of Chinese girls are bit players de ned by their allegiance to Nell, a con guration that reveals Stephensons inability to escape his own cultural biases in this otherwise cosmopolitan work.

s I suggested earlier, another utopian space no sooner constituted than imploded is A Young Ladys Illustrated Primer. The doubling motif, announced by the re exive play between Stephensons title and the Primer as a book within his book, sets the stage for a nested series of recursive loops. In the adventures of Nell we are presented with two landscapes, the coded simulation of the Primer and the real world, a doubling repeated within the Primer when Princess Nell encounters a series of castles and artifacts that turn out to be nothing other than Turing machines processing binary code, so that the algorithmic operations of the Primer are also represented within its simulated world. The rst castle sets the pattern. Nell, imprisoned by the Duke of Turing, begins receiving coded communications and must determine whether the encoder is a machine (in which case it is trying to trick her) or a human, the rightful Duke who has also been imprisoned by his machine. The keys Princess Nell collects on her quest in the Primer have a dual signi cance. In the simulated world they unlock doors, and in the algorithmic process producing this simulation they unlock the codes that control the Turing machines. In all the machines but the last, the Turing test always has the same outcome: the encoder is revealed as a mechanical system that Nell can bend to her bidding as soon as she masters the code. In typical romance fashion, the last castle is the most formidable, run by an impressive machine named Wizard 0.2, a name that playfully evokes Oz. In addition, 0.2 alludes both to a doubling (2) and an emptiness (0). Doubling and emptiness converge when Nell discovers there is no machine

138

N. Katherine Hayles

behind the curtain (hence the zero). But there is a human, none other than Hackworth himself, the artifex who designed the coding machine in which he also apparently resides, inscribing the doubling with yet another meaning. We may be tempted to read Princess Nells triumph as revealing the humanity at the heart of the machineuntil we remember that inside this human are nano-machines. The point lies neither with emptiness alone, that is, a regime of machines with no humans, nor with doubling alone, that is, a regime that endlessly self-reproduces the human. Rather the point (literally inscribed as a dot) is to connect both regimes in mutopic interpenetration. Nells quest is thus constituted as acquiring the skills that let her successfully expose the recursive loops connecting inside with outside, artifex with artifact, human with machine. This resolution is itself doubled in Nells dramatic rescue of Miranda, the ractor who has sacri ced her career to mother Nell through the mediation of the Primer. Determined to nd Nell, Miranda wants to reverse the one-way communication she has had with the Primer, in which she knows only the lines she reads and has to infer Nells situation from these. Tracing the reverse current is almost impossible, Carl Hollywood explains, because the dispersed nature of the Internet breaks information into small packets and sends it through multiple routes to its destination. Hollywood arranges for Miranda to meet the mysterious Beck, from whom she learns of his theory that human desire, although usually orthogonal to the ow of information (that is, mathematically independent of it), seems to achieve some kind of coupling through the Drummers. He suggests that Miranda join the Drummers and try to nd Nell by exploiting this coupling. Earlier Hackworth was drawn to the underwater world of the Drummers by Dr. Xs exhortation to Find the Alchemist, a recursive formulation in which his quest turns him into the person he seeks. There he witnesses a copulation ritual in which twelve Drummer men, aroused by the crowds drumming and chanting, all copulate with the same woman, whereupon her body bursts into ames from the heat thrown off by the thousands of semen-carried rod computers as they carry out their computations. In this copulation ritual human desire is harnessed to do the work of computation. Mirandas scheme would reverse this procedure, harnessing the computational power of the Drummers to do the work of desire. Nell rescues Miranda at the point where Miranda is about to become the recipient of the mens sperm in a ritual that would end with her spontaneous combustion. Surely it is signi cant that Mirandas desire by itself is not enough. Only when Nell completes the loop through her reciprocal desire to nd Miranda do the non-human operations of code receive the impress of human desire. This scenario hints that the recursive loops can lead to a broader sense of the human and an enhanced appreciation of complexity.

hese loops suggest a different interpretation for the disappearance of utopia than the observation with which I began, namely Rortys view that American contemporary writers have lost faith in their countrys ability to achieve greatness. It is useful to remember that the utopian genre, usually dated from Sir Thomas Mores classic Utopia in 1516, was formulated in societies that were not nearly as interconnected as todays. Cross-country communication took days in Mores time and was beset by many uncertainties, from highwaymen to a horses

Is Utopia Obsolete?

139

broken leg. Even in the nineteenth century, it took a full twenty four hours for a telegraph message to be transmitted around the globe. Now, of course, messages can ash around the earth in minutes, permitting the ever-tighter integration between social, economic, and information systems. The utopian ideal may be fading not because humans have lost hope for a better future but because the conditions in which we live make the isolationist premise of utopian spaces appear increasingly untenable. But this isolation is itself subject to scrutiny, as Louis Marin has pointed out, for it always implies a complementary perspective from which the dominated must look up to the dominating height of a privileged inside. Compared with a utopia, a mutopia may after all give us the greater reason to hope, for its foregrounding of the recursive loops that connect utopia to world, world to technological systems, and technological systems to people highlights the interdependencies that must form the basis for any responsible contemporary ethics. The fathersindeed all of uscan no longer afford to laugh at the idea that danger is an illusion and nature is impotent; we can no longer afford to believe that the actions of the dominators will not cycle through the system to affect them as well. Con icted, paradoxical, and far from innocent, Stephensons mutopia can recreate a new sense of the human even as it implodes older ideas of autonomous individualism and secure boundaries. We can do worse than be mutopians.

RECOMMENDED READINGS Csicsery-Ronay, Istvan. 1997. Notes on Mutopia. Postmodern Culture 8(1), www.jefferson. village.virginia.edu/pmc/contents.all.html Jameson, Fredric. 1992. Secondary Elaborations (Conclusion). In Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Marin, Louis. 1993. Frontiers of Utopia: Past and Present. Critical Inquiry 19 (Spring): 403411. Marin, Louis. 1984. Utopics: A Spatial Play. Robert A. Vollrath (trans.). New Jersey: Humanities Press. More, Thomas. 1965. Utopia. Paul Turner (trans.). New York: Viking. Rorty, Richard. 1999. Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Stephenson, Neal. 1996. The Diamond Age: or, A Young Ladys Illustrated Primer. New York: Bantam.

N. Katherine Hayles is a Professor of English and Design/Media Arts at the University of California, Los Angeles. She teaches and writes on the relations of literature, science, and technology in the twentieth and twenty- rst centuries. She is currently completing Writing Machines, a study of literature in the digital age, forthcoming in the Mediaworks Pamphlet series from the MIT Press in the fall of 2002. Correspondence : Department of English, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1530 , U.S.A. Email: nk hayles@yahoo.com

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Barth-Ethnicity and The Concept of CultureDocument9 paginiBarth-Ethnicity and The Concept of CulturefirefoxcatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumer Protection Act, ProjectDocument17 paginiConsumer Protection Act, ProjectPREETAM252576% (171)

- JANE GUYER Africa Has Never Been TraditionalDocument21 paginiJANE GUYER Africa Has Never Been TraditionalAndrea Thomas William PollioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vishnu and The Videogame: The Videogame Avatar and Hindu Philosophy.Document8 paginiVishnu and The Videogame: The Videogame Avatar and Hindu Philosophy.ARSGAMESÎncă nu există evaluări

- TURNER, Terence - The Social SkinDocument15 paginiTURNER, Terence - The Social Skinadrianojow100% (1)

- 02 Alaimo Thinking As Stuff OZone Vol1Document9 pagini02 Alaimo Thinking As Stuff OZone Vol1axiang88Încă nu există evaluări

- Constructing The Good Transsexual - Christine Jorgensen, Whiteness, and Heteronormativity in The Mid-Twentieth-Century-Press - Emily SkidmoreDocument32 paginiConstructing The Good Transsexual - Christine Jorgensen, Whiteness, and Heteronormativity in The Mid-Twentieth-Century-Press - Emily SkidmoreTaylor Cole MillerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Massumi - The Future Birth of The Affective FactDocument10 paginiMassumi - The Future Birth of The Affective FactMichael LitwackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baldacchino, Jean-Paul - The Anthropologist's Last Bow - Ontology and Mysticism in Pursuit of The Sacred (2019)Document21 paginiBaldacchino, Jean-Paul - The Anthropologist's Last Bow - Ontology and Mysticism in Pursuit of The Sacred (2019)Pedro SoaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Money Matters: Instability, Values, and Social Payments in The Modern History of West African Communities, Ed. by Jane I. Guyer Only Chapters by Guyer, Dupre, Guyer, Arhin, Ekejiuba, Manuh and Berry.Document159 paginiMoney Matters: Instability, Values, and Social Payments in The Modern History of West African Communities, Ed. by Jane I. Guyer Only Chapters by Guyer, Dupre, Guyer, Arhin, Ekejiuba, Manuh and Berry.OSGuinea100% (1)

- Holbraad. Response To Bruno Latour's Thou Shall Not Freeze-FrameDocument14 paginiHolbraad. Response To Bruno Latour's Thou Shall Not Freeze-FrameLevindo Pereira100% (1)

- Bernard Stiegler The Lost Spirit of Capitalism Disbelief and Discredit 3 1Document114 paginiBernard Stiegler The Lost Spirit of Capitalism Disbelief and Discredit 3 1mzzionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Varied Modal Verbs Exercises II PDFDocument10 paginiVaried Modal Verbs Exercises II PDFFrancisco Cañada Lopez100% (1)

- Nick Browne, The Political Economy of The Television Super TextDocument10 paginiNick Browne, The Political Economy of The Television Super TextMichael LitwackÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Conversation About CultureDocument16 paginiA Conversation About CulturefizaisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Spheres of ExchangeDocument24 paginiWhy Spheres of ExchangeBruno GoulartÎncă nu există evaluări

- 12-Give Me A LabDocument32 pagini12-Give Me A LabAimar Arriola100% (1)

- Post Human Assemblages in Ghost in The ShellDocument21 paginiPost Human Assemblages in Ghost in The ShellJobe MoakesÎncă nu există evaluări

- KOHN, Eduardo. Anthropology of OntologiesDocument21 paginiKOHN, Eduardo. Anthropology of OntologiesJeezaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emile Benveniste-Notion of RhythmDocument7 paginiEmile Benveniste-Notion of RhythmŽeljkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Michel de Certeau's HeterologyDocument11 paginiMichel de Certeau's HeterologyWelton Nascimento100% (1)

- Hirst P - Althusser and The Theory of IdeologyDocument29 paginiHirst P - Althusser and The Theory of IdeologyFrancisco LemiñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning To See in MelanesiaDocument19 paginiLearning To See in MelanesiaSonia LourençoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethnomethodology's Programme (Garfinkel)Document18 paginiEthnomethodology's Programme (Garfinkel)racorderovÎncă nu există evaluări

- After Monumentality: Narrative As A Technology of Memory in William Gass's The TunnelDocument32 paginiAfter Monumentality: Narrative As A Technology of Memory in William Gass's The TunnelekdorkianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charlotte Hooper Masculinities IR and The Gender VariableDocument18 paginiCharlotte Hooper Masculinities IR and The Gender VariableMahvish Ahmad100% (1)

- 10.4324 9780203093917 PreviewpdfDocument55 pagini10.4324 9780203093917 PreviewpdfYumicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Systems Theory in AnthropologyDocument17 paginiSystems Theory in AnthropologythersitesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kwakiutl F Boas PDFDocument288 paginiKwakiutl F Boas PDFEstela GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Escobar 2010 Postconstructivist-Political-Ecologies PDFDocument17 paginiEscobar 2010 Postconstructivist-Political-Ecologies PDFAmalric PouzouletÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trinh T Minh-Ha From Woman Native OtherDocument8 paginiTrinh T Minh-Ha From Woman Native OthergasparinflorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rethinking The SpectacleDocument20 paginiRethinking The SpectacleDENISE MAYE LUCEROÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ellen Rooney and Elizabeth Weed D I F F e R e N C e S in The Shadows of The Digital HumanitiesDocument173 paginiEllen Rooney and Elizabeth Weed D I F F e R e N C e S in The Shadows of The Digital HumanitiesLove KindstrandÎncă nu există evaluări

- What's Within - Nativism Reconsidered PDFDocument178 paginiWhat's Within - Nativism Reconsidered PDFarezooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Goldman & Vignemont 2009 Is Social Cognition EmbodiedDocument6 paginiGoldman & Vignemont 2009 Is Social Cognition EmbodiedRicardo Jose De LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dan ZahaviDocument5 paginiDan ZahaviganzichÎncă nu există evaluări

- D. Boyer, "The Medium of Foucault" (2003)Document9 paginiD. Boyer, "The Medium of Foucault" (2003)Francois G. RichardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tania Li - Practices of Assemblage and Community Forest ManagementDocument32 paginiTania Li - Practices of Assemblage and Community Forest ManagementAlejandro Alfredo HueteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thinking Ecology The Mesh The Strange STDocument29 paginiThinking Ecology The Mesh The Strange STJulie WalterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kaja Silverman The Subject of SemioticsDocument217 paginiKaja Silverman The Subject of SemioticssmbtigerÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Introduction To OOF Behar OOF TPDFDocument36 paginiAn Introduction To OOF Behar OOF TPDFjcbezerraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vieweswaran - Histories of Feminist Ethnography.Document32 paginiVieweswaran - Histories of Feminist Ethnography.akosuapaolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1989 Intro Creativity of PowerDocument12 pagini1989 Intro Creativity of PowerRogers Tabe OrockÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ellen Rooney. "A Semi-Private Room"Document30 paginiEllen Rooney. "A Semi-Private Room"s0metim3sÎncă nu există evaluări

- Latour, Bruno. (2013) Biography of An Inquiry On A Book About Modes of ExistenceDocument16 paginiLatour, Bruno. (2013) Biography of An Inquiry On A Book About Modes of ExistencerafaelfdhÎncă nu există evaluări

- ONG, Aihwa Neoliberalism As Mobile TechnologyDocument6 paginiONG, Aihwa Neoliberalism As Mobile TechnologyDaniel OrozcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Depressive Realism: An Interview With Lauren Berlant: Earl MccabeDocument7 paginiDepressive Realism: An Interview With Lauren Berlant: Earl Mccabekb_biblio100% (1)

- The Gramscian MomentDocument6 paginiThe Gramscian MomentBodhisatwa RayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ortner - Reflections On Studying in HollywoodDocument24 paginiOrtner - Reflections On Studying in HollywoodanacandidapenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Documentary TrinhMinhHaDocument24 paginiDocumentary TrinhMinhHaJean BrianteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Border Thinking and Disidentification PoDocument18 paginiBorder Thinking and Disidentification PoBohdana KorohodÎncă nu există evaluări

- COULDRY, Nick. Why Voice Matters. Culture and Politics After NeoliberalismDocument185 paginiCOULDRY, Nick. Why Voice Matters. Culture and Politics After NeoliberalismCarolinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Latour and Literary StudiesDocument6 paginiLatour and Literary StudiesDiego ShienÎncă nu există evaluări

- INGOLD, Tim. The Architect and The Bee. 1983.Document21 paginiINGOLD, Tim. The Architect and The Bee. 1983.Luísa GirardiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Donzelot Anti SociologyDocument28 paginiDonzelot Anti SociologyEliran Bar-El100% (2)

- Bruno Latour - Will Non-Humans Be SavedDocument21 paginiBruno Latour - Will Non-Humans Be SavedbcmcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life and Words: Violence and The Descent Into The Ordinary (Veena Das)Document5 paginiLife and Words: Violence and The Descent Into The Ordinary (Veena Das)Deep Kisor Datta-RayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhizomatic Reflections: Discourses on Religion and TheologyDe la EverandRhizomatic Reflections: Discourses on Religion and TheologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- More-Than-Human Choreography: Handling Things Between Logistics and EntanglementDe la EverandMore-Than-Human Choreography: Handling Things Between Logistics and EntanglementÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Funeral Casino: Meditation, Massacre, and Exchange with the Dead in ThailandDe la EverandThe Funeral Casino: Meditation, Massacre, and Exchange with the Dead in ThailandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Envisioning Eden: Mobilizing Imaginaries in Tourism and BeyondDe la EverandEnvisioning Eden: Mobilizing Imaginaries in Tourism and BeyondÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ansell - What Is A Democratic ExperimentDocument12 paginiAnsell - What Is A Democratic ExperimentmzzionÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Postcapitalist Politics - JK Gibson-GrahamDocument316 paginiA Postcapitalist Politics - JK Gibson-GrahamsherahfaulknerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Utopia of Endless ExploitationDocument6 paginiUtopia of Endless ExploitationÖzlem YıldızÎncă nu există evaluări

- SwissRe Understanding ReinsuranceDocument23 paginiSwissRe Understanding ReinsuranceHaldi Zusrijan PanjaitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- IO FormativeDocument3 paginiIO Formativenb6tckkscvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Debt Collectors - Georgia Consumer Protection Laws & Consumer ComplaintsDocument11 paginiDebt Collectors - Georgia Consumer Protection Laws & Consumer ComplaintsMooreTrustÎncă nu există evaluări

- CatalogDocument11 paginiCatalogFelix Albit Ogabang IiiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arvind Medicare v. Neeru MehraDocument21 paginiArvind Medicare v. Neeru MehraSparsh GoelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burns: Sept 2015 East of England CT3 DaysDocument29 paginiBurns: Sept 2015 East of England CT3 DaysThanujaa UvarajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Question Bank Unit 2 SepmDocument2 paginiQuestion Bank Unit 2 SepmAKASH V (RA2111003040108)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of MagnetiteDocument23 paginiThe Effects of MagnetiteavisenicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inesco Amc 2106735164Document3 paginiInesco Amc 2106735164spahujÎncă nu există evaluări

- Railway StoresDocument3 paginiRailway Storesshiva_gulaniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toad For Oracle Release Notes 2017 r2Document30 paginiToad For Oracle Release Notes 2017 r2Plate MealsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dear John Book AnalysisDocument2 paginiDear John Book AnalysisQuincy Mae MontereyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Media ServerDocument2 paginiIntegrated Media ServerwuryaningsihÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shortcomings of The Current Approaches in TH Pre-Service and In-Service Chemistry Teachers TrainingsDocument5 paginiShortcomings of The Current Approaches in TH Pre-Service and In-Service Chemistry Teachers TrainingsZelalemÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Use The Fishbone Tool For Root Cause AnalysisDocument3 paginiHow To Use The Fishbone Tool For Root Cause AnalysisMuhammad Tahir NawazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical Research 2Document11 paginiPractical Research 2Angela SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Equipment List ElectricalDocument4 paginiEquipment List ElectricalKaustabha DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Material 1 (Writing Good Upwork Proposals)Document3 paginiMaterial 1 (Writing Good Upwork Proposals)OvercomerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mohave PlacersDocument8 paginiMohave PlacersChris GravesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enlightened Despotism PPT For 2 Hour DelayDocument19 paginiEnlightened Despotism PPT For 2 Hour Delayapi-245769776Încă nu există evaluări

- Individual Defending SessionDocument6 paginiIndividual Defending SessionAnonymous FN27MzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burdah EnglishDocument2 paginiBurdah EnglishArshKhan0% (1)

- MT 103 FAQ'sDocument20 paginiMT 103 FAQ'sja_mufc_scribd0% (1)

- People V Jacalne y GutierrezDocument4 paginiPeople V Jacalne y Gutierrezhmn_scribdÎncă nu există evaluări

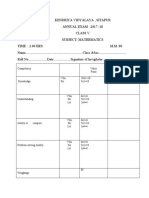

- Class V Maths Annual 2017 18Document9 paginiClass V Maths Annual 2017 18Pravat TiadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 2Document5 paginiUnit 2Vee Walker CaballeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faculty of English: Hanoi Open UniversityDocument15 paginiFaculty of English: Hanoi Open UniversityNguyễn Hương NhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cottage in The Woods by Katherine Coville - Chapter SamplerDocument40 paginiThe Cottage in The Woods by Katherine Coville - Chapter SamplerRandom House KidsÎncă nu există evaluări