Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

W Se 20100102

Încărcat de

DOUDOU-38Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

W Se 20100102

Încărcat de

DOUDOU-38Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Water Science and Engineering, 2010, 3(1): 14-22 doi:10.3882/j.issn.1674-2370.2010.01.

002

http://www.waterjournal.cn e-mail: wse2008@vip.163.com

Application of HEC-HMS for flood forecasting in Misai and Wanan catchments in China

James Oloche OLEYIBLO*, Zhi-jia LI

College of Hydrology and Water Resources, Hohai University, Nanjing 210098, P. R. China Abstract: The hydrologic model HEC-HMS (Hydrologic Engineering Center, Hydrologic Modeling System), used in combination with the Geospatial Hydrologic Modeling Extension, HEC-GeoHMS, is not a site-specific hydrologic model. Although China has seen the applications of many hydrologic and hydraulic models, HEC-HMS is seldom applied in China, and where it is applied, it is not applied holistically. This paper presents a holistic application of HEC-HMS. Its applicability, capability and suitability for flood forecasting in catchments were examined. The DEMs (digital elevation models) of the study areas were processed using HEC-GeoHMS, an ArcView GIS extension for catchment delineation, terrain pre-processing, and basin processing. The model was calibrated and verified using historical observed data. The determination coefficients and coefficients of agreement for all the flood events were above 0.9, and the relative errors in peak discharges were all within the acceptable range. Key words: hydrologic model; HEC-HMS; catchment delineation; DEM; terrain pre-processing; Misai Catchment; Wanan Catchment

1 Introduction

HEC-1 is a mathematical watershed model that contains several methods with which to simulate surface runoff and river/reservoir flow in river basins. The hydrologic model, together with flood damage computations (also included in the model), provides a basis for evaluation of flood control projects. The HEC-1 hydrologic model was originally developed in 1967 by Leo R. Beard and other staff members of the Hydrologic Engineering Center, with the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, to simulate flood hydrographs in complex river basins (Singh 1982). Since then, the program has undergone a revision: different versions of the model with greatly expanded capabilities have been released. This study used the HEC-HMS Version 2.2.1. The HEC model is designed to simulate the surface runoff response of a catchment to precipitation by representing the catchment with interconnected hydrologic and hydraulic components. It is primarily applicable to flood simulations. In HEC-HMS, the basin model comprises three vital processes; the loss, the transform and the base flow. Each element in the model performs different functions of the precipitation-runoff process within a portion of the catchment or basin known as a sub-basin. An element may depict a surface runoff, a stream

*Corresponding author (e-mail: evangjamesa1@yahoo.com; evangjamesa1@gmail.com) Received Nov. 3, 2009; accepted Dec. 23, 2009

channel, or a reservoir. Each of the elements is assigned a variable which defines the particular attribute of the element and mathematical relations that describe its physical processes. The result of the modeling process is the computation of stream flow hydrographs at the catchment outlet.

2 What necessitates hydrologic modeling

The design, construction and operation of many hydraulic projects require an adequate knowledge of the variation of the catchments runoff, and for most of these problems it would be ideal to know the exact magnitude and the actual time of occurrence of all stream flow events during the construction period and economic life of the project. If this information was available at the project planning and design stages, it would be possible to select from amongst all alternatives a design, construction program, and operational procedure that would produce a project output with an optimized objective function. Unfortunately, such ideal and precise information is never available because it is impossible to have advance knowledge of the project hydrology for water resources development projects; it is necessary to develop plans, designs, and management techniques using a hypothetical set of future hydrologic conditions. It is the determination of these future hydrologic conditions that has long occupied the attention of engineering hydrologists who have attempted to identify acceptable simplifications of complex hydrologic phenomena and to develop adequate models for the prediction of the responses of catchments to various natural and anthropogenic hydrologic and hydraulic phenomena. In view of these, a number of hydrologic models have been developed for flood forecasting and the study of rainfall-runoff processes (Crawford and Linsley 1966; Burnash et al. 1973; Sugawara 1979; Beven and Kirkby 1979; Sivapalan et al. 1987; Zhao 1992; Todini 1996). In recent times, GIS (geographic information systems) has become an integral part of hydrologic studies because of the spatial character of the parameters and precipitation controlling hydrologic processes. GIS plays a major role in distributed hydrologic model parameterization. This is to overcome gross simplifications made through representation by lumping of parameters at the river basin scale. The extraction of hydrologic information, such as flow direction, flow accumulation, watershed boundaries, and stream networks, from a DEM (digital elevation model) is accomplished through GIS applications. This study combined GIS with HEC-HMS, and analyzed the models suitability for the studied catchments.

3 Methodology

The methodology can be divided into four major tasks: (1) obtaining the geographic locations of the studied basins; (2) DEM processing, delineating streams and watershed characteristics, terrain processing, and basin processing; (3) importing the processed data to HMS; and (4) merging the observed historical data with the processed DEM for model simulations.

James Oloche OLEYIBLO et al. Water Science and Engineering, Mar. 2010, Vol. 3, No. 1, 14-22

15

4 Study areas and data processing

4.1 Study areas

The model was applied to two catchments: the Misai and Wanan Catchments. The Misai Catchment is in Zhejiang Province, in southern China. It has a total of six rain gauge measurement stations: Qixi, Majin, Yanxi, Daxibian, Huanglinkang, and Misai. The catchment has a total area of 797 km2. The Wanan Catchment is in Anhui Province, in southern China. It has a total of four rain gauge measurement stations: Xiuning, Yixian, Yanqian, and Rucun. The catchment has a total area of 869 km2. The region is very similar to the Misai Catchment; in fact, they are neighboring catchments, both mountainous with thick vegetation cover, very fertile with a highly permeable upper layer soil profile, and humid.

4.2 Data processing

30" 30" resolution DEMs were generated from data provided by the U. S. Geological Survey (USGS) (NGDC 2009), from the website. The hydrologic models were generated with the help of HEC-GeoHMS (USACE 2000a, 2000b) using DEMs of the study areas (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Using DEM terrain data, HEC-GeoHMS produces HMS input files, a stream network, sub-basin boundaries, and connectivity of various hydrologic elements in an ArcView GIS environment via a series of steps called terrain pre-processing and basin processing. The physical representation of catchments and rivers was configured in the basin models, and hydrologic elements were linked.

Fig. 1 Misai Catchment raw DEM

Fig. 2 Wanan Catchment raw DEM

4.3 Terrain pre-processing

Determination of a hydrologically correct DEM and its derivatives, mainly the flow direction and flow accumulation grids, often demands some iteration of drainage path calculations in order to precisely depict the flow of water through the catchment, the hydrologically correct DEM must have a resolution sufficient to capture the details of surface flow. Problems often arise when the drainage area has a coarse resolution. These problems can be overcome if proper care is taken in the terrain pre-processing stage to produce a fine

16

James Oloche OLEYIBLO et al. Water Science and Engineering, Mar. 2010, Vol. 3, No. 1, 14-22

resolution of the drainage area. To obtain the DEM used to delineate various components of the catchments used for this study, the following steps were taken. 4.3.1 Filling sinks A sink is a cell with no clear or defined drainage direction; all surrounding cells have higher elevation, resulting in stagnation of water. To overcome this problem, the sink has to be filled by modifying the elevation value. Once the sinks in a DEM are removed by breaching and filling, the resulting flat surface must still be interpreted to define the surface drainage pattern, because there is no flow on flat areas by definition, so the next step in the procedure requires that flow direction be assigned. The elevation of pit cells is simply increased until a down-slope path to a cell becomes available, under the constraint that flow may not return to a pit cell. 4.3.2 Flow direction The flow direction was derived from the filled grid based on the premise that water flows downhill, and will follow the steepest descent direction. It provides the flat filled surface with a slope to enable water flow freely downward without having to be impounded or trapped. This was done by the assigned gentle slope to the filled grid DEM until the steepest descent direction was achieved. Water can flow from one cell to one of its eight adjacent cells in the steepest descent direction. 4.3.3 Flow accumulation Based on the derived flow direction grid, the flow accumulation was calculated. A flow accumulation grid was calculated from the flow direction grid. The flow accumulation records the number of cells that drain into an individual cell in the grid. The flow accumulation grid is essentially the area of drainage to a specific cell measured in grid units. The flow accumulation grid is the core grid in stream delineation. 4.3.4 Stream definition The threshold area was assigned to the flow accumulation grid in order to obtain the stream flow path. The stream flow path is defined by a number of cells that accumulate in an area before they are recognized.

5 Model application and calibration

In this study, 16 flood events that occurred during the seven-year period of 1982-1988 in the Misai Catchment and 15 flood events from 1987 and 2002 (there were no data from the period of 1998-2001) in the Wanan Catchment were used for model testing. These data were obtained from the Chinese Hydrological Year Book. HMS uses a project name as an identifier for a hydrologic model. An HMS project must have the following components before it can be run: a basin model, a meteorological model, and control specifications. The basin model and basin features were created in the form of a background map file imported to HMS from the data derived through HEC-GeoHMS for model simulation (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). The observed

James Oloche OLEYIBLO et al. Water Science and Engineering, Mar. 2010, Vol. 3, No. 1, 14-22

17

precipitation and discharge data were used to create the meteorological model using the user gauge weighting method and, subsequently, the control specification model was created. The control specifications determine the time pattern for the simulation; its features are: a starting date and time, an ending date and time, and a computation time step. To run the system, the basin model, the meteorological model, and the control specifications were combined. The observed historical data of six precipitation stations representing each sub-catchment and one stream gauge station in the Misai Catchment, and four precipitation stations representing each sub-catchment and one stream gauge station in the Wanan Catchment, were used for model calibration and verification. An hourly time step was used for the simulation based on the time interval of the available observed data.

Fig. 3 Processed results for Misai Catchment imported to HMS for simulation

Fig. 4 Processed results for Wanan Catchment imported to HMS for simulation

The initial and constant method was employed to model infiltration loss. The SCS (Soil Conservation Service) unit hydrograph method was used to model the transformation of precipitation excess into direct surface runoff. The exponential recession model was employed to model baseflow. The Muskingum routing model was used to model the reaches. The trial and error method, in which the hydrologist makes a subjective adjustment of parameter values in between simulations in order to arrive at the minimum values of parameters that give the best fit between the observed and simulated hydrograph, was employed to calibrate the model. The criterion used to evaluate the fit was the determination coefficient (DC). Although the model was calibrated manually, the HEC-HMS built-in automatic optimization procedure was used to authenticate the acceptability and suitability of the parameter values and their ranges as applicable to their uses in HEC-HMS. The choice of the objective function depends upon the need. Here, percentage error in peak flow and volume were employed during the optimization and implementation of the univariate gradient search method. The recession constant was 0.70. As stated earlier, ten flood events that occurred over four years in the Misai Catchment were used for model calibration, and six flood events that occurred over three years in the

James Oloche OLEYIBLO et al. Water Science and Engineering, Mar. 2010, Vol. 3, No. 1, 14-22

18

Misai Catchment were used for model verification. In the Wanan Catchment, nine flood events that occurred over eight years were used to calibrate the model and six flood events that occurred over four years were used for model verification.

6 Results and discussion

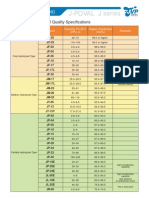

As described in the introduction, each component of HEC-HMS models an aspect of the precipitation-runoff process within a portion of the basin, commonly referred to as a sub-basin. Representation of a component requires a set of parameters that specify the particular characteristics of the component and mathematical relations that describe the physical processes (Singh 1982). Tables 1 and 2 below show the calibrated parameter values of each of the components represented in this model. Apart from the sub-areas, which are fixed, parameters were calibrated simultaneously through adjustment of their values until a good agreement between the observed and simulated hydrographs was achieved.

Table 1 Calibrated parameter values of Misai Catchment

Sub-basin Qixi Majin Yanxi Daxibian Huanglinkang Misai Area (km2) 207.22 162.59 130.71 131.51 89.26 75.71 SCS lag (min) 510 400 518 391 450 240 Recession constant 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 Threshold discharge (ratio to peak) 0.12 0.12 0.12 0.12 0.12 0.12 Muskingum coefficient X 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 K (h) 1 1 1 1 1 1

Table 2 Calibrated parameter values of Wanan Catchment

Sub-basin Xiuning Yixian Yanqian Rucun Area (km2) 106.51 271.53 246.85 240.91 SCS lag (min) 450 500 500 450 Recession constant 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 Threshold discharge (ratio to peak) 0.12 0.12 0.12 0.12 Muskingum coefficient X 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 K (h) 1 1 1 1

The calibration and validation graphs of the two catchments are shown below. Figs. 5 through 8 show good agreement between observed and simulated graphs. Also, Tables 3 and 4 show observed and simulated values, as well as DC values, for both calibration and validation of the two catchments. Qs is the simulated discharge, Qo is the observed discharge, and DC is defined as follows:

DC = 1

y (i )

i =1 c

y o (i )

2

i =1

yo (i ) yo

(1)

where yo ( i ) is the observed discharge for each time step i, yc ( i ) is the simulated value at time step i, yo is the mean observed discharge, and n is the total number of values within the time period.

James Oloche OLEYIBLO et al. Water Science and Engineering, Mar. 2010, Vol. 3, No. 1, 14-22

19

Fig. 5 Observed vs. simulated discharge in 1982 for calibration

Fig. 6 Observed vs. simulated discharge in 1986 for validation

Fig. 7 Observed vs. simulated discharge in 1990 for calibration

Fig. 8 Observed vs. simulated discharge in 2002 for validation

Table 3 Calibration and validation results for Misai Catchment

Period Date 1982-04-02 1982-06-19 1983-05-29 1983-06-14 Calibration 1983-06-20 1984-04-02 1984-05-12 1984-06-07 1985-05-04 1985-07-03 1986-05-19 1986-07-04 Validation 1987-04-25 1987-05-26 1987-06-20 1988-06-21 Qs (m3/s) 344.99 1 642.30 1 728.00 942.27 1 447.60 798.05 269.36 287.01 758.76 398.25 1 251.50 275.37 284.00 201.10 1 371.90 1 211.00 Qo (m3/s) 345 1 650 1 820 942 1 420 795 279 287 745 398 1 240 267 271 207 1 370 1 220 Q (m3/s) 0.01 7.70 92.00 0.27 27.60 3.05 9.64 0.01 13.75 0.25 11.50 8.71 12.61 5.70 1.90 9.00 Relative error (%) 0 0.46 5.10 0.03 1.94 1.38 3.25 0 1.85 0.06 0.93 3.30 4.64 2.85 0.14 0.74

t (min)

DC 0.99 0.99 0.92 0.99 0.98 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.95 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.97

0 0 60 0 60 10 0 60 0 60 0 10 0 30 0 10

Note: Q is error in peak discharge and t is peak time error.

20

James Oloche OLEYIBLO et al. Water Science and Engineering, Mar. 2010, Vol. 3, No. 1, 14-22

Table 4 Calibration and validation results for Wanan Catchment

Period Date 1987-07-02 1988-06-16 1989-05-20 1990-06-13 Calibration 1991-06-30 1992-06-20 1993-05-27 1993-06-28 1994-05-01 1995-05-15 1995-06-30 Validation 1996-06-01 1996-06-23 1997-07-05 2002-06-18 Qs ( (m3/s) 723.16 731.28 553.72 1 350.30 1 656.30 790.04 870.21 1 164.90 1 192.10 1 657.40 1 576.10 798.60 2 850.10 759.66 1 785.00 Qo (m3/s) 780 727 526 1 260 1 840 797 888 1 920 1 290 1 814 1 480 803 2 970 779 1 720 Q (m3/s) 56.84 4.28 27.72 90.30 183.70 6.96 17.79 755.10 97.90 156.60 96.10 44.00 119.90 19.34 65.00 Relative error (%) 7.30 0.58 5.26 7.20 9.98 0.87 2.00 19.30 7.60 8.63 6.49 0.55 4.04 2.50 3.80

t (min)

DC 0.95 0.99 0.99 0.99 0.89 0.99 0.99 0.83 0.74 0.99 0.95 0.83 0.76 0.97 0.99

60 0 0 0 0 10 5 20 40 40 60 60 0 0 60

It can be seen in the above graphs that the simulated and observed peak discharges occurred on the same day, and their maximum time difference was one hour, which is acceptable for flood forecasting. The entire DC for the Misai Catchment was above 0.9, while in the Wanan Catchment there were two DC values below the acceptable value: 0.74 and 0.76. Li et al. (2008) applied the Xinanjiang model to the Misai Catchment with the same data set and obtained almost the same results.

7 Conclusions

As shown in the results above, the model predicted peak discharge accurately based on the available historical flood data. Both the flood volume and timing were fairly accurate. This shows that HEC-HMS is suitable for the studied catchments. From the results, we can conclude that the complexity of the model structure does not determine its suitability and efficiency. Though the structure of HEC-HMS is simple, it is a powerful tool for flood forecasting. A further application of HEC-HMS should be encouraged to confirm its suitability for the Chinese catchments.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the use of observation data from the Chinese Hydrological Year Book, and to thank Hohai University in Nanjing, P. R. China, for supporting this study.

References

Beven, K. J., and Kirkby, M. J. 1979. A physically based variable contributing area model of basin hydrology. Hydrological Sciences Bulletin, 24(1), 43-69. Burnash, R. J., Ferra, R. L., and McGuire, R. A. 1973. A General Stream Flow Simulation System Conceptual Modeling for Digital Computer. Sacramento: Joint Federal State River Forecasts Center.

James Oloche OLEYIBLO et al. Water Science and Engineering, Mar. 2010, Vol. 3, No. 1, 14-22

21

Chow, V. T., Maidment, D. R., and Mays, L. W. 1988. Applied Hydrology. New York: McGraw-Hill.Clarke, R. T. 1975. Prediction in catchment hydrology. Chapman, T. G., and Dunin, F. X., eds., Proceedings of a National Symposium on Hydrology, 482. Canberra: Australian Academy of Science. Crawford, N. H., and Linsley, R. K. 1966. Digital Simulation in Hydrology: The Stanford Watershed Model IV Technical Report. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University. Li, S. Y., Qi, R. Z., and Jia, W. W. 2008. Calibration of the conceptual rainfall-runoff models parameters. Proceeding of 16th IAHR-APD Congress and 3rd Symposium of IAHR-ISHS, 55-59. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press. National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC). http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/cgi-bin/mgg/ff/nph-newform.pl/ mgg/topo/customdatacd/ [Retrieved Oct. 6, 2009] Singh, V. P. 1982. Applied Modeling in Catchment Hydrology. Littleton, CO: Water Resources Publications. Sivapalan, M., Beven, K. J., and Wood, E. F. 1987. On hydrologic similarity 2: A scale model of storm runoff production. Water Resources Research, 23(12), 2266-2278. Sugawara, M. 1979. Automatic calibration of the tank model. Hydrological Sciences Bulletin, 24(3), 375-388. Todini, E. 1996. The ARNO rainfall-runoff model. Journal of Hydrology, 175(1-4), 339-382. [doi: 10.1016/S0022-1694(96)80016-3] U. S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). 2000a. Geospatial modeling extension. HEC-GeoHMS, Users Manual. Davis, CA: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Hydrologic Engineering Center. U. S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). 2000b. Hydrologic Modeling System: Technical Reference Manual. Davis, CA: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Hydrologic Engineering Center. Zhao, R. J. 1992. The Xinanjiang model applied in China. Journal of Hydrology, 135(1-4), 371-381. [doi: 10.1016/0022-1694(92)90096-E]

22

James Oloche OLEYIBLO et al. Water Science and Engineering, Mar. 2010, Vol. 3, No. 1, 14-22

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- (James S Monroe Reed Wicander) Physical Geology PDFDocument672 pagini(James S Monroe Reed Wicander) Physical Geology PDFCUCAÎncă nu există evaluări

- The History of Gilmanton - Including What Is Now GilfordDocument314 paginiThe History of Gilmanton - Including What Is Now GilfordCharles CarterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Do Moti CZ ManualDocument36 paginiDo Moti CZ ManualtonitonitoneÎncă nu există evaluări

- CAD StandardsDocument92 paginiCAD StandardsDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- EF03074-Bluetooth Bee (HC-05 and HC-06) User GuideDocument7 paginiEF03074-Bluetooth Bee (HC-05 and HC-06) User GuideDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- WIFI Relay ModuleDocument14 paginiWIFI Relay ModuleDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Do Moti CZ ManualDocument36 paginiDo Moti CZ ManualtonitonitoneÎncă nu există evaluări

- BIOS Configuration Utility User Guide PDFDocument22 paginiBIOS Configuration Utility User Guide PDFDallas OaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02 PDFDocument5 pagini02 PDFDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Concept of A Learning Robot Based On VSLADocument7 paginiConcept of A Learning Robot Based On VSLADOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- 02 PDFDocument5 pagini02 PDFDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- DS QlikView For Financial Planning and Analysis enDocument2 paginiDS QlikView For Financial Planning and Analysis enDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Hello WorldDocument1 paginăHello WorldDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Describing People and Place - Bigpa 28 Mei 2013Document6 paginiDescribing People and Place - Bigpa 28 Mei 2013DOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Terminal Services and CitrixDocument6 paginiTerminal Services and CitrixDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Hello WorldDocument1 paginăHello WorldDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Hello WorldDocument1 paginăHello WorldDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Planification LineaireDocument22 paginiPlanification LineaireDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Hello WorldDocument1 paginăHello WorldDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Watershed and Stream Network Delineation: Adapted From Arc Hydro Tools - TutorialDocument41 paginiWatershed and Stream Network Delineation: Adapted From Arc Hydro Tools - TutorialDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- CycleDocument10 paginiCycleDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- JW - Hec-Ras 10 StepsDocument28 paginiJW - Hec-Ras 10 StepszimbapdfÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design MethodologyDocument24 paginiDesign Methodologyᔡᙍᖇᘜᓿᘮ ᑢᕼᓬÎncă nu există evaluări

- IELTS GlossaryDocument3 paginiIELTS GlossarynotesmetalÎncă nu există evaluări

- TopconPS-As SitePrep April2013Document1 paginăTopconPS-As SitePrep April2013DOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- 07 Hydrants Page 19Document1 pagină07 Hydrants Page 19DOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- Water Distribution Network PDFDocument45 paginiWater Distribution Network PDFVisal ChengÎncă nu există evaluări

- BrochureDocument8 paginiBrochureDOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- English Lesson 5: Active and Passive Voice The Paragraph Adverbs Idioms Vocabulary and SpellingDocument20 paginiEnglish Lesson 5: Active and Passive Voice The Paragraph Adverbs Idioms Vocabulary and SpellingIqbal AhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Distribution Network PDFDocument45 paginiWater Distribution Network PDFVisal ChengÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pva01 1Document2 paginiPva01 1DOUDOU-38Încă nu există evaluări

- 5 Runoff and Factors Affecting ....Document32 pagini5 Runoff and Factors Affecting ....Aafaque HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- IntroductionDocument8 paginiIntroductionYannick HowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homeowners Guide To Stormwater BMP Maintenance: What You Need To Know To Take Care of Your PropertyDocument24 paginiHomeowners Guide To Stormwater BMP Maintenance: What You Need To Know To Take Care of Your PropertyClaire KidwellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper On SwatDocument6 paginiResearch Paper On Swatt1s1gebes1d3100% (3)

- Mekonnen Haile PDFDocument17 paginiMekonnen Haile PDFRas MekonnenÎncă nu există evaluări

- © Ncert Not To Be Republished: The FightDocument10 pagini© Ncert Not To Be Republished: The FightKalpavriksha1974Încă nu există evaluări

- Strahler 1952 Dynamic Basis of Geomorphology GeologyDocument18 paginiStrahler 1952 Dynamic Basis of Geomorphology GeologyAmarílis Donald100% (1)

- River LandformsDocument2 paginiRiver LandformsRajnish kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter Two Rainfall-Runoff Relationships 2.0 Runoff: Engineering Hydrology Lecture Note 2018Document46 paginiChapter Two Rainfall-Runoff Relationships 2.0 Runoff: Engineering Hydrology Lecture Note 2018Kefene GurmessaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bridge Scour and Stream Instability Countermeasures - FHWA NHI 01-003 PDFDocument402 paginiBridge Scour and Stream Instability Countermeasures - FHWA NHI 01-003 PDFmarco noaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 7 - The Hydrosphere and Water PollutionDocument8 paginiModule 7 - The Hydrosphere and Water Pollutionjuliaroxas100% (1)

- Environmental Impacts of Bauxite and Gold Mining in Nassau Mountains, Suriname. J.H. Mol Paramaribo, February 2009Document9 paginiEnvironmental Impacts of Bauxite and Gold Mining in Nassau Mountains, Suriname. J.H. Mol Paramaribo, February 2009Suriname MirrorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hydrology ReviewerDocument3 paginiHydrology ReviewerMisael CamposanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Changes in Stream Flow and Sediment Discharge and The Response To Human Activities in The Middle Reaches of The Yellow RiverDocument3 paginiChanges in Stream Flow and Sediment Discharge and The Response To Human Activities in The Middle Reaches of The Yellow Riverteme beyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Goemorphology 5NDocument13 paginiGoemorphology 5Nshuvobosu262Încă nu există evaluări

- Topic 1Document33 paginiTopic 1Adron LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- L2 Hydraulic Study (F)Document64 paginiL2 Hydraulic Study (F)Ram KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Duthmala The Morphodynamic Functioning of The Dom-Hydrotheek (Stowa) 444915Document104 paginiDuthmala The Morphodynamic Functioning of The Dom-Hydrotheek (Stowa) 444915LisaStrakhovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Selina Concise Geography Solutions Class 9 Chapter 10 DenudationDocument5 paginiSelina Concise Geography Solutions Class 9 Chapter 10 DenudationArgha senguptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geological Society of America Bulletin: Hypsometric (Area-Altitude) Analysis of Erosional TopographyDocument27 paginiGeological Society of America Bulletin: Hypsometric (Area-Altitude) Analysis of Erosional TopographyValter AlbinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis 16 03 2019 PDFDocument74 paginiThesis 16 03 2019 PDFibrahim jamal AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Know Your Creek Norman 2008Document16 paginiKnow Your Creek Norman 2008Jayden BredhauerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comp Lindberg CappresentDocument61 paginiComp Lindberg Cappresentapi-316819120Încă nu există evaluări

- Earth ScienceDocument41 paginiEarth ScienceOmar EssamÎncă nu există evaluări

- The River SevernDocument7 paginiThe River SevernMarius BuysÎncă nu există evaluări

- Os Mosteiros No Deserto Da JordaniaDocument20 paginiOs Mosteiros No Deserto Da JordaniaPauloRoldãoÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALP EIS Main ReportDocument332 paginiALP EIS Main ReportRonald EwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science: Fourth Quarter - Module 2A Conservation of Water ResourcesDocument25 paginiScience: Fourth Quarter - Module 2A Conservation of Water Resourcesrollen grace fabulaÎncă nu există evaluări