Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

CBA Household Debt Trends (25 July 2013)

Încărcat de

leithvanonselenDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

CBA Household Debt Trends (25 July 2013)

Încărcat de

leithvanonselenDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Global Markets Research

Issues

25 July 2013

Household debt trends

Australian households have housing debt levels that are high by international standards. But income and asset characteristics of relevant households suggest that they can service the debt comfortably. Housing loans make up the largest component of household debt while housing is generally the largest asset. In the past few years Australian households have become more cautious about committing to higher housing debt and continue to save slightly more than 10% of their income, the highest level since the 1980s. The current period of low interest rates has seen households maintaining debt repayment schedules and consolidating their balance sheets. Gradually rising housing prices should enhance their net asset positions.

Australian household debt ratios are relatively high by international standards. But there are important economic and legal differences between housing markets that can sustain marked variations in housing prices. In Australia, it is also important to understand the economic and social characteristics of the households that have the debt. This note uses the considerable amount of research into household financial positions (published by the ABS, the RBA and other groups like the Melbourne Institutes 2012 Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) report) which provide extensive insights into these household characteristics. The data and the surveys show that household debt has increased steadily over 2002-2010, primarily due to growth in housing-related debt. But the data and the surveys also indicate that the households who carry the most debt typically have stable characteristics. On average, these households are couples with good health, high educational attainment, relatively high and stable incomes and in a prime age category. On balance, Australian households are in a good position to service their housing and other debt. The net asset positions of the households are also important in judging their capacity to cope with adverse economic developments. One of the more interesting recent trends is that households have also increased their housing debt prepayments over 2012 and 2013, by leaving their repayments unchanged while interest rates fell. It is in line with the inclination to reduce housing and credit card debt since the GFC. Combined, these more cautionary shifts provide households with an important buffer to any negative economic shocks. Some commentary on Australian household balance sheet positions conveys the impression that household debt levels are too high, leaving many households with unmanageable debt servicing commitments. The general line is that a significant number of households are at risk of financial ruin if their economic circumstances, like employment, change adversely. The surveys, and the experience of the past few decades, does not, in our view, support those lines of argument. The experience of the post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) period was a stress test that indicated the ability of Australian households to cope well with adverse economic developments. Some of the commentary on Australian house prices, especially from offshore based groups, argues that there is a housing price bubble in Australia which will eventually burst and replicate the downward path of US and UK house prices through the 2008 to 2011 post-GFC period. In our view, the US and UK housing market outcomes reflected the severe recessions and the housing demand/supply imbalances that hit the two economies after the GFC. Fortunately, through good luck and good management, Australia did not have a recession and the most important influence on the housing markets outcomes, the unemployment rate, peaked at just under 6%. That was significantly below the peaks reached in the US and UK where the rates are moving lower but are still around 8%.

Michael Workman Senior Economist T. +612 9118 1019 E. michael.workman@cba.com.au Diana Mousina Economist T. +612 9118 6394 E. diana.mousina@cba.com.au

Important Disclosures and analyst certifications regarding subject companies are in the Disclosure and Disclaimer Appendix of this document and at www.research.commbank.com.au. This report is published, approved and distributed by Commonwealth Bank of Australia ABN 48 123 123 124 AFSL 234945.

Global Markets Research | Economics: Issues

HOUSEHOLD LIABILITIES

Household Balance Sheets Some commentary has Some commentary on Australian balance sheet trends concludes that Australian household Australian household debt levels as too high. debt levels are too high and that there has been unsustainable growth in debt positions. Following that line of argument, households may not be well placed to deal with negative economic shocks like job loss. Some debt to income ratios are relatively high . The survey evidence does not show undue vulnerability. At first glance, some debt ratios indicate that households are sitting on relatively large liabilities. The average debt-to-disposable (or after tax) income ratio, for example, is at 147%, a 28% increase on ten years ago. And, Australian liabilities (as a % of disposable or after-tax income) are significantly above our global peers. But global debt comparisons may be unreliable because of the difficulty in sourcing comparable data on the level of house prices across countries. Another offsetting issue is the often neglected asset side of the household balance sheet. Looking at the Australian debt-to-assets ratio paints a much stronger picture of overall household financial positions. The average debt-to-assets ratio sits at a respectable, and relatively low, 17.6%. Debt often has negative connotations attached to it. But, it can often be used for a valuable purpose. If borrowing is being used to fund investment, for example, then there could be a productivity gain. Its also important to consider who holds the debt. The debt may be held by high-income households, using the tax effective provisions like negative gearing, to fund property and share portfolio investments. HILDA Data

% 190

(% of disposable income)

Australia Japan US

% 190

143

143

UK 95

France 95 Italy

48

NZ

48

Source: OECD/RBNZ/RBA

0 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012

H/HOLD SAVINGS & DEBTS

%

(% of disposable income)

12 Housing debt servicing

12

H'hold savings ratio

0 ABS & CBA -4 Mar-90 Mar-94 Mar-98 Mar-02 Mar-06 Mar-10

% 160 Debt-todisposable income ratio (lhs) 120 Debt-toassets ratio (rhs) 80

-4

Debt can often be used for valuable and productive purposes e.g. borrowing to fund investment.

AUST HOUSEHOLD DEBT

% 20

16

12

We are able to analyse trends in household We can analyse debt positions using the HILDA data changes in debt (Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in positions using the Australia). The study takes a sample of HILDA (Household, Australian households occupying private Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia). dwellings across 2002-2010. The HILDA report looks at the distribution of debt across each household (but not by individuals). Growth in debt levels The number of households holding debt has increased marginally. According to the HILDA data, the proportion of households holding debt has increased marginally over 2002-2010. In 2010, around 69% of households held some debt (compared to 65% in 2002). So just under a third of Australian households are living debt-free. The level of debt that households are carrying has also increased. The mean debt level of households is around $151,488. But, the median level of debt is much lower at $20,081.

Source: RBA 40 Sep-1988 Sep-1996 Sep-2004 8 Sep-2012

DEBT ACROSS HOUSEHOLDS

'000's 160 Source: HILDA 2013 Mean ($) 120 120 '000's 160

80

80

40 Median ($) 0 2002 2006 2010

40

But there has been quite a large increase in debt levels.

Global Markets Research | Economics: Issues

The mean level of debt is skewed upwards because there are a small number of (high income) households in the sample that hold relatively high debt levels. Nevertheless, growth in both the mean and median levels of debt over 2002-2010 has been significant. It is important to consider where the growth in Which areas of debt have grown the most? debt has occurred. Has it occurred in typically problem areas like credit card debt? Or has it occurred in areas like housing or other property debt that have a corresponding asset attachment?

%

30

RBA CREDIT AGGREGATES

(annual % change)

%

30

Business credit

20 20

10

Housing credit Personal credit

10

Total

-10 Jan-02 Jan-04 Jan-06 Jan-08 Jan-10 Jan-12 -10

COMPOSITION OF DEBT AMONGST HOUSEHOLDS WITH DEBT

(share of each type of debt, by level of debt, %, 2010)

80 Source: HILDA 2013

60

Other Debt 40 Credit Card Debt 20 Other Property Debt 0 Bottom quintile 2nd quintile 3rd quintile 4th quintile Top quintile HECS Debt Home Debt Business Debt

Credit card debt is declining as a proportion of total debt and is only significant for the bottom two debt quintiles.

Credit card debt is often seen to be quite a persistent component of the Australian debt landscape. But, according to the HILDA data, credit card debt is only important for the bottom debt quintile (those households with the lowest debt levels). For these households, credit card debt made up around a third of total debt outstanding in 2010. This proportion may seem large but in value terms it only equates to around $1,000. For other debt quintiles, credit card debt is small (under 11% of total debt) and has been declining as a proportion of total debt. Higher income groups tend to prefer lower cost debt, like re-drawable mortgages. Credit card activity is currently subdued, with average credit card balances declining and slow growth in credit card cash advances. As a result, growth in credit card debt is likely to remain weak over the near-term. Housing debt, on average, is the largest source of household debt. And the value of this debt tends to be large. In 2010, the top debt quintile held around $355K in housing debt. Debt on other (e.g. investment) property is also increasing in significance. In 2010, other property debt made up 29% of debt for the top

%pa 12

CREDIT CARD ACTIVITY

(%pa, smthd)

%pa 12

Source: RBA

8 Balances

Total Accounts Avge balance per card

Future growth in credit card debt is likely to be subdued.

-4

Jan-08 Jan-09 Jan-10 Jan-11 Jan-12 Jan-13

-4

CREDIT CARD CASH ADVANCES

% 24

(annual % change*)

% 24

12

12

Housing debt is the largest source of household debt. Other property debt is increasing in significance.

-12

-12

*smoothed

-24 Jul-99 Jul-01 Jul-03 Jul-05 Jul-07 Jul-09 Jul-11

-24

Global Markets Research | Economics: Issues

quintile. In 2002 it made up a smaller 23%.

%

HOUSEHOLD INDEBTEDNESS

(median)

Source: HILDA 2013

% 10

The majority of the increase in household debt over 2002-2010 was growth in housing loans.

So it is fair to conclude that most of the households who hold the most debt (in value terms) hold a residential property. From this conclusion we can assume that the majority of the increase in household debt over 2002-2010 was growth in housing loans. Is the growth in household debt positions a problem? To answer this question we need to determine how many households have debt levels that may become difficult to service. Levels of indebtedness

34

31 Household debt: Household assets (rhs) 27 Household debt: Household income (lhs) 24

20 2002 2006 2010

There has been little change in the household debt-toassets ratio.

Household indebtedness can be determined through examining household debt ratios. In the HILDA survey, the median level of household debt made up 9% of assets in 2010. This was unchanged on the 2006 level and only marginally higher than in 2002. There was also little change in households with excessive debt-to-assets ratio (above 0.75 or 1). Therefore, the debt-to-assets ratio indicates that there has been little change in household indebtedness. The household debt-to-income ratio indicates the ability of households to service debt. Using this ratio, household indebtedness looks to have increased more significantly. In 2010, the household debt to income ratio was 33%, from 22% in 2002. More significantly, there has been significant growth in households with excessive debt-to-income ratios. Excessive debt is defined by a debt-to-assets ratio that is greater than 0.75 and a debt-to-income ratio greater than 4. In 2002, around 8% of households had a high debt-to-income ratio (above 4). This increased to 13.1% in 2010. And 6.2% of households had a debt-to-income ratio above 6 in 2010 which was an increase from 4% in 2002. There is some evidence that the levels of households with dangerous debt levels has increased. Examining the characteristics of households with these high debt levels is also important to determine the ease with which the debt is serviced. Characteristics of debt holders

% 14

EXCESSIVE DEBT-TO-INCOME

(% with high ratio, median)

Source: HILDA 2013

11 >4

7 >6

Lift in the debt-toincome ratio.

0 2002 2006 2010

% 8

EXCESSIVE DEBT-TO-ASSETS

(% with high ratio, median)

Source: HILDA 2013 >0.75

>1 4

0 2002 2006 2010

AUST H/H ASSETS BY RISK

% 75

(% of total)

% 75

Fairly safe

50

50

The persistent and excessive debt group.

The most concerning debt holdings are those that are persistent and excessive. The HILDA data analyses the characteristics of households that have both persistent and excessive levels of debt. Based on the HILDA study, a couple household (with or without dependent children) are the most likely to have an excessive debt-toincome ratio compared to a single household.

Safe 25 25

Fairly risky 0

Source: CBA (e)

0 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010

Global Markets Research | Economics: Issues

But, a couple household are also more likely to have a larger pool of assets, relative to their debt. And the debt-toassets ratio tends to decline with age. A households debt-to-assets ratio tends to decline with age. The probability of a high debt-to-income ratio peaks in the 35-44 age category and then declines. This occurs because the majority of household debt is held on the family home and as you move through age brackets, the equity in the family home increases as debt is repaid. The healthiness of a household tends to be positively associated with a higher debt-toincome ratio. Similarly for educational attainment. Therefore, a higher degree of education tends to be associated with a higher debt-to-income ratio. The conclusion from these characteristics is that households that are typically associated with better economic outcomes (e.g. better health, higher educational attainment, prime age, couple household) are all often associated with higher indebtedness (higher debt-toincome ratios). Households ability to service debt. From this data we can conclude that households that are better able to cope with higher debt levels are the ones taking it on. As well, high debt is often matched by high levels of assets. This would mean that a sudden loss of income would require (at worst) a household to sell down their assets. On average, it would therefore appear that households are in a good position to deal with high levels of debt. APRA and RBA data confirms this view with recent arrears trends suggesting limited stress in an aggregate sense. Housing-related debt Housing debt plays a large part in the debt landscape. The majority of the growth in household debt over 2002-2010 was due to increasing housingrelated debt. Owner-occupied debt was $867bn in March 2013, about twice as much as investor-related debt of $413bn. It is important to consider the relative importance of housing to other forms of debt and whether households are in the position to finance the typical housing loan. The answer depends on income and asset positions. Housing ratios, such as the housing debt to disposable income are at historically high levels (see facing chart) which indicate that the housing debt burden is large. But it has stabilised over the past 5 years as the household savings ratio moved to the 10% level, the highest since the 1980s. Taking a closer look at repayment trends we find that households appear to be in control of

% 35

AUSTRALIAN HOUSING DEBT

Housing debt-todisposable income ratio (lhs)

% 150

26 Housing debt-tohousing assets ratio (rhs) 18

113

75

38

Household characteristics.

Source: RBA 0 Sep-1988 Sep-1996 Sep-2004 0 Sep-2012

PRINCIPAL REPAYMENTS

$bn

(cumulative overpayment)

$bn

30

30

20

20

10

10

0 Sep-97

Dec-02

Mar-08

0 Jun-13

*assumes prinipal repayment ratio fixed at 1995-98 level

REPAYMENT RATES

% 15

Annual change in customers repaying above required rate (lhs) Change in mortgage rate (inverse, rhs)

% -4.0

10

-3.0

-2.0

-1.0

-5

0.0

-10

1.0

-15 Jan-05

2.0 Jan-08 Jan-11

$bn 1400

HOUSING DEBT STOCK

(quarterly, outstanding)

$bn 1400

1200 Investor 1000

1200

1000

800

800

600 Owneroccupied

600

400

400

200 Sep-99

200 Sep-02 Sep-05 Sep-08 Sep-11

Global Markets Research | Economics: Issues

these relatively large debt positions. They have taken advantage of lower interest rates to prepay debt, reducing the average term of mortgages and lifting their net equity positions. Home ownership rates Home ownership rates falling. One indicator of a shift in the willingness, or financial ability, to take on any or more housingrelated debt is home ownership rates. The HILDA survey indicates that there has been a downward shift, from 2001 to 2010, in the proportion of households that are in owneroccupied dwellings. If the current trend to household savings ratios of around 10% is maintained in the next few years then it is possible that ownership rates could continue their gradual slide. It means that more households, as in Europe, would prefer long term renting to ownership. It could also mean investor-related lending takes a gradually larger proportion of total housing debt. Typically, about two thirds of households in the States and Territories are owner-occupiers. But, from the HILDA survey, the downward shift seen in national home ownership rates shift is not uniform across the States. Small rises occurred in Qld, WA and the ACT but were offset by falls in NSW, Vic, SA, Tas and NT. Home values and net equity Negative equity trending higher. The value of a house to a households net wealth position needs to be judged against the amount of housing debt. The HILDA survey gives a measure of the mean home equity from 2001 to 2010, showing a significant rise over the period. It is in line with the rise in home values over the same period. The survey also gives some details on the percentage of households facing negative equity positions (where debt is larger than house value) over the period. It has also been rising, from just under 2% to over 2.5%. The measure displays some volatility through the survey period. So, even though house prices rose there is a consistent trend upwards in negative equity. The rate of home ownership increases with age, which is what should be expected. Mainly because incomes increase with age and dual income partnerships rise sharply from the late teens to the late twenties. But the interesting shift is the significant decline in ownership rates by the middle aged groups who have been in the past the major change-up buyers. Reluctance to take on more housing debt, possibly because of job uncertainty, could be the factors causing the shift. It means relatively slower housing credit growth in the future if it continues.

% 70

HOME OWNERSHIP RATES

(2001 to 2010)

Proportion of households that are owner-occupied

% 70

68

68

66

66

64

Proportion of people who own their own home*

64

62 Source: HILDA 60 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 *People aged 18 or over

62

60

% 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 -6

OWNER -OCCUPIED HOUSEHOLDS

(Mean rate %, 2001 to 2010)

% 80

Home ownership rates, rhs

70

60

Change in rate, 2001 to 2010, lhs Source: HILDA

50

-8 NSW VIC QLD SA WA TAS NT ACT

40

HOME OWNER EQUITY

% 4.0

(home value minus home debt)

2010 $000s 450

3.0

Mean home equity $000s, rhs

400

2.0 % with negative equity, lhs

350

1.0

300

Source: HILDA 0.0 2001 2004 2007 2010 250

% 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 -6 -8 -10

HOME OWNERSHIP RATES

(by age group, 2001 to 2010)

Mean home ownership rates, rhs

% 100

Home ownership rates rise with age.

80

60

40

Change in rate, 2001 to 2010, lhs Source: HILDA 18-24 25-24 35-44 45-54 55-64 65 & over

20

Global Markets Research | Economics: Issues

International house prices International house prices diverging. Housing is generally the major asset of households. In Australia, for instance, the value of the house in 2010 was around 45% of total household assets. So trends in housing prices have significant bearings on relative financial positions of households across economies. According to OECD data, Australian house prices were around 40% higher in 2012 than they were in 2004. Higher housing prices means the asset position of households here has improved. In comparison, the US and UK housing price outcomes through and after the GFC have been relatively poor. The UKs house prices are 20% higher than 2004 but have been essentially been flat since 2007. In comparison US house prices are back to their 2004 levels and about 20% below the pre-GFC levels. Note that the commodity exporting economies of Norway, Canada, New Zealand and Australia have fared better, in terms of housing prices, than the US and the UK since the GFC. International unemployment rates

100

HOUSE PRICES

(Nominal, 2004=100)

180 170 160 150 Australia 140 130 120 110 100 OECD 90 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 US UK New Zealand Norway Canada

REAL HOUSE PRICES

(2004=100)

160 150 140 130 120 110 Germany Australia Canada Norway

Unemployment rates are a major influence on housing issues.

One of the biggest threats to a stable housing market and household asset outcomes, is job loss and higher unemployment rates. It usually results in forced property sales which reduce prices. The GFC caused severe economic recessions in the US and the EU. Unemployment rates rose to their highest levels since the early 1990s recession. The GFC recession was driven by a major global credit squeeze. The outcomes of the two recessions were similar - unemployment rate rose dramatically, except in those countries that avoided recession, like Australia. Importantly, it helps explain why Australias house prices are still relatively high compared to the US and UK. Conclusions

90 OECD 80 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 US

UK

12

% 12

UNEMPLOYMENT RATE

Euro zone United States

% 12

8 UK Australia

4 Japan

Source: CEIC

Conclusions.

Survey data indicates that household debt levels in Australia are relatively high by international standards. But, it also shows that most indebted Australian households are well placed to service it with a reasonable buffer to negative economic shocks, like higher unemployment rates. The evidence indicates that most of the housing-related debt is held by the higher income households, who can more easily service it. Home ownership rates in Australia have declined gradually over the past decade as household savings have risen and households have become slightly more adverse to higher debt levels. It points to continued modest growth in housing credit.

0 Jan 05

Index 115

0 Jan 07 Jan 09 Jan 11 Jan 13

Index 115

REAL GDP

(Sep'08= 100)

Australia

110 Lehman collapse 105 NZ

110

US

105

100 UK 95 Japan Europe

100

95

90 Mar-08 Mar-09 Mar-10 Mar-11 Mar-12 Mar-13

90

Global Markets Research | Economics: Issues

Please view our website at www.research.commbank.com.au. The Commonwealth Bank of Australia ABN 48 123 123 124 AFSL 234945 ("the Bank") and its subsidiaries, including Commonwealth Securities Limited ABN 60 067 254 399 AFSL 238814 ("CommSec"), Commonwealth Australia Securities LLC, CBA Europe Ltd and Global Markets Research, are domestic or foreign entities or business areas of the Commonwealth Bank Group of Companies (CBGOC). CBGOC and their directors, employees and representatives are referred to in this Appendix as the Group. This report is published solely for informational purposes and is not to be construed as a solicitation or an offer to buy any securities or financial instruments. This report has been prepared without taking account of the objectives, financial situation and capacity to bear loss, knowledge, experience or needs of any specific person who may receive this report. No member of the Group does, or is required to, assess the appropriateness or suitability of the report for recipients who therefore do not benefit from any regulatory protections in this regard. All recipients should, before acting on the information in this report, consider the appropriateness and suitability of the information, having regard to their own objectives, financial situation and needs, and, if necessary seek the appropriate professional, foreign exchange or financial advice regarding the content of this report. We believe that the information in this report is correct and any opinions, conclusions or recommendations are reasonably held or made, based on the information available at the time of its compilation, but no representation or warranty, either expressed or implied, is made or provided as to accuracy, reliability or completeness of any statement made in this report. Any opinions, conclusions or recommendations set forth in this report are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to the opinions, conclusions or recommendations expressed elsewhere by the Group. We are under no obligation to, and do not, update or keep current the information contained in this report. The Group does not accept any liability for any loss or damage arising out of the use of all or any part of this report. Any valuations, projections and forecasts contained in this report are based on a number of assumptions and estimates and are subject to contingencies and uncertainties. Different assumptions and estimates could result in materially different results. The Group does not represent or warrant that any of these valuations, projections or forecasts, or any of the underlying assumptions or estimates, will be met. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The Group has provided, provides, or seeks to provide, investment banking, capital markets and/or other services, including financial services, to the companies described in the report and their associates. This report is not directed to, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of or located in any locality, state, country or other jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject any entity within the Group to any registration or licensing requirement within such jurisdiction. All material presented in this report, unless specifically indicated otherwise, is under copyright to the Group. None of the material, nor its content, nor any copy of it, may be altered in any way, transmitted to, copied or distributed to any other party, without the prior written permission of the appropriate entity within the Group. In the case of certain products, the Bank or one of its related bodies corporate is or may be the only market maker. The Group, its agents, associates and clients have or have had long or short positions in the securities or other financial instruments referred to herein, and may at any time make purchases and/or sales in such interests or securities as principal or agent, including selling to or buying from clients on a principal basis and may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with this report. US Investors: If you would like to speak to someone regarding the subject securities described in this report, please contact Commonwealth Australia Securities LLC (the US Broker-Dealer), a broker-dealer registered under the U.S. Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the Exchange Act) and a member of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) at 1 (212) 336-7737. This report was prepared, approved and published by Global Markets Research, a division of Commonwealth Bank of Australia ABN 48 123 123 124 AFSL 234945 ("the Bank") and distributed in the U.S. by the US Broker-Dealer. The Bank is not registered as a broker-dealer under the Exchange Act and is not a member of FINRA or any U.S. self-regulatory organization. Commonwealth Australia Securities LLC (US Broker-Dealer) is a wholly owned, but non-guaranteed, subsidiary of the Bank, organized under the laws of the State of Delaware, USA, with limited liability. The US Broker-Dealer is not authorized to engage in the underwriting of securities and does not make markets or otherwise engage in any trading in the securities of the subject companies described in our research reports. The US Broker-Dealer is the distributor of this research report in the United States under Rule 15a-6 of the Exchange Act and accepts responsibility for its content. Global Markets Research and the US Broker-Dealer are affiliates under common control. Computation of 1% beneficial ownership is based upon the methodology used to compute ownership under Section 13(d) of the Exchange Act. The securities discussed in this research report may not be eligible for sale in all States or countries, and such securities may not be suitable for all types of investors. Offers and sales of securities discussed in this research report, and the distribution of this report, may be made only in States and countries where such securities are exempt from registration or qualification or have been so registered or qualified for offer and sale, and in accordance with applicable broker-dealer and agent/salesman registration or licensing requirements. The preparer of this research report is employed by Global Markets Research and is not registered or qualified as a research analyst, representative, or associated person under the rules of FINRA, the New York Stock Exchange, Inc., any other U.S. self-regulatory organization, or the laws, rules or regulations of any State. European Investors: This report is published, approved and distributed in the UK by the Bank and by CBA Europe Ltd (CBAE). The Bank and CBAE are both registered in England (No. BR250 and 05687023 respectively) and authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Services Authority (FSA). This report does not purport to be a complete statement or summary. For the purpose of the FSA rules, this report and related services are not intended for retail customers and are not available to them. The products and services referred to in this report may put your capital at risk. Investments, persons, matters and services referred to in this report may not be regulated by the FSA. CBAE can clarify where FSA regulations apply. Singapore Investors: This report is distributed in Singapore by Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Singapore Branch (company number F03137W) and is made available only for persons who are Accredited Investors as defined in the Singapore Securities and Futures Act and the Financial Advisers Act. It has not been prepared for, and must not be distributed to or replicated in any form, to anyone who is not an Accredited Investor. Hong Kong Investors: This report was prepared, approved and published by the Bank, and distributed in Hong Kong by the Bank's Hong Kong Branch. The Hong Kong Branch is a registered institution with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority to carry out the Type 1 (Dealing in securities) and Type 4 (Advising on securities) regulated activities under the Securities and Futures Ordinance. Investors should understand the risks in investments and that prices do go up as well as down, and in some cases may even become worthless. Research report on collective investment schemes which have not been authorized by the Securities and Futures Commission is not directed to, or intended for distribution in Hong Kong. All investors: Analyst Certification and Disclaimer: Each research analyst, primarily responsible for the content of this research report, in whole or in part, certifies that with respect to each security or issuer that the analyst covered in this report: (1) all of the views expressed accurately reflect his or her personal views about those securities or issuers; and (2) no part of his or her compensation was, is, or will be, directly or indirectly, related to the specific recommendations or views expressed by that research analyst in the report. The analyst(s) responsible for the preparation of this report may interact with trading desk personnel, sales personnel and other constituencies for the purpose of gathering, synthesizing, and interpreting market information. Directors or employees of the Group may serve or may have served as officers or directors of the subject company of this report. The compensation of analysts who prepared this report is determined exclusively by research management and senior management (not including investment banking). No inducement has been or will be received by the Group from the subject of this report or its associates to undertake the research or make the recommendations. The research staff responsible for this report receive a salary and a bonus that is dependent on a number of factors including their performance and the overall financial performance of the Group, including its profits derived from investment banking, sales and trading revenue. Unless agreed separately, we do not charge any fees for any information provided in this presentation. You may be charged fees in relation to the financial products or other services the Bank provides, these are set out in the relevant Financial Services Guide (FSG) and relevant Product Disclosure Statements (PDS). Our employees receive a salary and do not receive any commissions or fees. However, they may be eligible for a bonus payment from us based on a number of factors relating to their overall performance during the year. These factors include the level of revenue they generate, meeting client service standards and reaching individual sales portfolio targets. Our employees may also receive benefits such as tickets to sporting and cultural events, corporate promotional merchandise and other similar benefits. If you have a complaint, the Banks dispute resolution process can be accessed on 132221. Unless otherwise noted, all data is sourced from Australian Bureau of Statistics material (www.abs.gov.au).

Global Markets Research | Economics: Issues

Research

Commodities Luke Mathews Lachlan Shaw Vivek Dhar Agri Commodities Mining & Energy Commodities Mining & Energy Commodities Telephone +612 9118 1098 +613 9675 8618 +613 9675 6183 Email Address luke.mathews@cba.com.au lachlan.shaw@cba.com.au vivek.dhar@cba.com.au

Economics Michael Blythe Michael Workman John Peters Gareth Aird Diana Mousina Chief Economist Senior Economist Senior Economist Economist Economist

Telephone +612 9118 1101 +612 9118 1019 +612 9117 0112 +612 9118 1100 +612 9118 6394

Email Address michael.blythe@cba.com.au michael.workman@cba.com.au john.peters@cba.com.au gareth.aird@cba.com.au diana.mousina@cba.com.au

Fixed Income Adam Donaldson Scott Rundell Philip Brown Alex Stanley Tariq Chotani Tally Dewan Kevin Ward Head of Debt Research Chief Credit Strategist Fixed Income Quantitative Strategist Interest Rate Strategist Credit Research Analyst Credit Research Analyst Database Manager

Telephone +612 9118 1095 +612 9303 1577 +612 9118 1090 +612 9118 1125 +612 9280 8058 +612 9118 1105 +612 9118 1960

Email Address adam.donaldson@cba.com.au scott.rundell@cba.com.au philip.brown@cba.com.au alex.stanley@cba.com.au tariq.chotani@cba.com.au tally.dewan@cba.com.au kevin.ward@cba.com.au

Foreign Exchange and International Economics Richard Grace Joseph Capurso Peter Dragicevich Andy Ji Chris Tennent-Brown Martin McMahon Chief Currency Strategist & Head of International Economics Currency Strategist Currency Strategist Asian Currency Strategist FX Economist Economist Europe

Telephone +612 9117 0080 +612 9118 1106 +612 9118 1107 +65 6349 7056 +612 9117 1378 +44 20 7710 3918

Email Address richard.grace@cba.com.au joseph.capurso@cba.com.au peter.dragicevich@cba.com.au andy.ji@cba.com.au chris.tennent.brown@cba.com.au martin.mcmahon@cba.com.au

Delivery Channels & Publications Monica Eley Ai-Quynh Mac Internet/Intranet Information Services

Telephone +612 9118 1097 +612 9118 1102

Email Address monica.eley@cba.com.au maca@cba.com.au

New Zealand Nick Tuffley Jane Turner Christina Leung Daniel Smith ASB Chief Economist Economist Economist Economist

Telephone +649 301 5659 +649 301 5660 +649 301 5661 +649 301 5853

Email Address nick.tuffley@asb.co.nz jane.turner@asb.co.nz christina.leung@asb.co.nz daniel.smith@asb.co.nz

Sales

Institutional Syd FX Fixed Income Japan Desk Melb Telephone +612 9117 0190 +612 9117 0341 +612 9117 0020 +612 9117 0025 +613 9675 6815 +613 9675 7495 +613 9675 6618 +613 9675 7757 Lon FX Credit HK Sing NY +44 20 7329 6266 +44 20 7329 6609 +852 2844 7539 +65 6349 7074 +1212 336 7750 Debt & Derivatives +44 20 7329 6444 Corporate NSW VIC SA/NT WA QLD NZ Metals Desk Agri Desk Telephone +612 9117 0377 +612 9675 7737 +618 8463 9011 +618 9215 8201 +617 3015 4525 +64 9375 5738 +612 9117 0069 +612 9117 0145 Equities Syd Asia Lon/Eu NY Telephone +612 9118 1446 +613 9675 6967 +44 20 7710 3573 +1212 336 7749

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- RP Data Property Pulse (11 October 2013)Document1 paginăRP Data Property Pulse (11 October 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phat Dragons Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (19 Sept 2013)Document3 paginiPhat Dragons Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (19 Sept 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Westpac Red Book (September 2013)Document28 paginiWestpac Red Book (September 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wilson HTM Valuation Dashboard (17 Sept 2013)Document20 paginiWilson HTM Valuation Dashboard (17 Sept 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wilson HTM - ShortAndStocky (20130916)Document22 paginiWilson HTM - ShortAndStocky (20130916)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- HSBC China Flash PMI (23 Sept 2013)Document3 paginiHSBC China Flash PMI (23 Sept 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- ANZ Property Industry Confidence Survey December 2013Document7 paginiANZ Property Industry Confidence Survey December 2013leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- RP Data Weekend Market Summary WE 13 Sept 2013Document2 paginiRP Data Weekend Market Summary WE 13 Sept 2013Australian Property ForumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aig Pci August 2013Document2 paginiAig Pci August 2013leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Media Release - The Vote Housing Special-1Document3 paginiMedia Release - The Vote Housing Special-1leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- HIA Dwelling Approvals (10 September 2013)Document5 paginiHIA Dwelling Approvals (10 September 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saul Eslake - Henry George Dinner Sep 2013 (Slides)Document13 paginiSaul Eslake - Henry George Dinner Sep 2013 (Slides)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phat Dragon Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (6 September 2013)Document3 paginiPhat Dragon Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (6 September 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phat Dragons Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (28 August 2013)Document3 paginiPhat Dragons Weekly Chronicle of The Chinese Economy (28 August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- RP Data - Rising Sales To Benefit Agents (August 2013)Document1 paginăRP Data - Rising Sales To Benefit Agents (August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- NZ PC On Aucklands MUL (March 2013)Document23 paginiNZ PC On Aucklands MUL (March 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Westpac - Where Have The FHBs Gone (August 2013)Document6 paginiWestpac - Where Have The FHBs Gone (August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- HIA - Housing Activity During Business Cycles (August 2013)Document8 paginiHIA - Housing Activity During Business Cycles (August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- RBA Statement of Monetary Policy (August 2013)Document62 paginiRBA Statement of Monetary Policy (August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weekend Market Summary Week Ending 2013 August 25 PDFDocument2 paginiWeekend Market Summary Week Ending 2013 August 25 PDFLauren FrazierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phat Dragon (23 August 2013)Document3 paginiPhat Dragon (23 August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- ANZ - Retail Sales Vs Online Sales (August 2013)Document4 paginiANZ - Retail Sales Vs Online Sales (August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Westpac - Fed Doves Might Have Last Word (August 2013)Document4 paginiWestpac - Fed Doves Might Have Last Word (August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- RP Data - Brisbane & Adelaide Housing (15 August 2013)Document1 paginăRP Data - Brisbane & Adelaide Housing (15 August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- ME Bank Household Financial Comfort Report (July 2013)Document32 paginiME Bank Household Financial Comfort Report (July 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- RP Data Home Values Results (July 2013)Document4 paginiRP Data Home Values Results (July 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shale - The New World (ANZ Research - August 2013)Document18 paginiShale - The New World (ANZ Research - August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- RP Data - Steady Decline in Home Ownership (8 August 2013)Document1 paginăRP Data - Steady Decline in Home Ownership (8 August 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genworth Streets Ahead Report (July 2013)Document8 paginiGenworth Streets Ahead Report (July 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Age Bias in The Australian Welfare State (ANU 2013)Document16 paginiAge Bias in The Australian Welfare State (ANU 2013)leithvanonselenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Bpats Enhancement Training ProgramDocument1 paginăBpats Enhancement Training Programspms lugaitÎncă nu există evaluări

- lý thuyết cuối kì MNCDocument6 paginilý thuyết cuối kì MNCPhan Minh KhuêÎncă nu există evaluări

- Opposition To Motion To DismissDocument24 paginiOpposition To Motion To DismissAnonymous 7nOdcAÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Police Commission: Interior and Local Government Act of 1990" As Amended by Republic Act No. 8551Document44 paginiNational Police Commission: Interior and Local Government Act of 1990" As Amended by Republic Act No. 8551April Elenor Juco100% (1)

- Torts Project22Document10 paginiTorts Project22Satyam SoniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamentals of Criminal Investigation and IntelligenceDocument189 paginiFundamentals of Criminal Investigation and IntelligenceGABRIEL SOLISÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Lewis Snead v. W. Frank Smyth, JR., Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 273 F.2d 838, 4th Cir. (1959)Document6 paginiJohn Lewis Snead v. W. Frank Smyth, JR., Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 273 F.2d 838, 4th Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managing Wholesalers N FranchisesDocument45 paginiManaging Wholesalers N FranchisesRadHika GaNdotra100% (1)

- Military Discounts For Universal Studio Tours 405Document2 paginiMilitary Discounts For Universal Studio Tours 405Alex DA CostaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Payroll AuditDocument11 paginiPayroll AuditJerad KotiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Non Banking Financial CompanyDocument39 paginiNon Banking Financial Companymanoj phadtareÎncă nu există evaluări

- COM670 Chapter 5Document19 paginiCOM670 Chapter 5aakapsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Untitled DocumentDocument16 paginiUntitled DocumentJolina CabardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fitzgerald TransformationOpenSource 2006Document13 paginiFitzgerald TransformationOpenSource 2006muthu.manikandan.mÎncă nu există evaluări

- QCP Installation of Ahu FahuDocument7 paginiQCP Installation of Ahu FahuThulani DlaminiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1394308827-Impressora de Etiquetas LB-1000 Manual 03 Manual Software BartenderDocument55 pagini1394308827-Impressora de Etiquetas LB-1000 Manual 03 Manual Software BartenderMILTON LOPESÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maxwell-Boltzmann Statistics - WikipediaDocument7 paginiMaxwell-Boltzmann Statistics - WikipediaamarmotÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 - Site Crisis Management Plan TemplateDocument42 pagini2 - Site Crisis Management Plan Templatesentryx1100% (7)

- Grant, R - A Historical Introduction To The New TestamentDocument11 paginiGrant, R - A Historical Introduction To The New TestamentPaulo d'OliveiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recio Garcia V Recio (Digest)Document3 paginiRecio Garcia V Recio (Digest)Aljenneth MicallerÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Salvatore Salamone, 902 F.2d 237, 3rd Cir. (1990)Document6 paginiUnited States v. Salvatore Salamone, 902 F.2d 237, 3rd Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motion For Preliminary InjunctionDocument4 paginiMotion For Preliminary InjunctionElliott SchuchardtÎncă nu există evaluări

- CFS Session 1 Choosing The Firm Financial StructureDocument41 paginiCFS Session 1 Choosing The Firm Financial Structureaudrey gadayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kajian 24 KitabDocument2 paginiKajian 24 KitabSyauqi .tsabitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2000 CensusDocument53 pagini2000 CensusCarlos SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Passbolt On AlmaLinux 9Document12 paginiPassbolt On AlmaLinux 9Xuân Lâm HuỳnhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study Analysis - Coca Cola CaseDocument10 paginiCase Study Analysis - Coca Cola CasePushpa BaruaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Security Administration GuideDocument416 paginiSecurity Administration GuideCauã VinhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASME - Lessens Learned - MT or PT at Weld Joint Preparation and The Outside Peripheral Edge of The Flat Plate After WDocument17 paginiASME - Lessens Learned - MT or PT at Weld Joint Preparation and The Outside Peripheral Edge of The Flat Plate After Wpranav.kunte3312Încă nu există evaluări

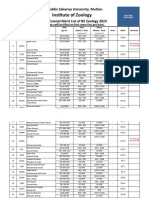

- 5953-6th Merit List BS Zool 31-8-2023Document22 pagini5953-6th Merit List BS Zool 31-8-2023Muhammad AttiqÎncă nu există evaluări