Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

MR1344 ch8

Încărcat de

Anonymous hWj4HKIDOFTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

MR1344 ch8

Încărcat de

Anonymous hWj4HKIDOFDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Chapter Eight

REGIONAL CONSEQUENCES OF INDONESIAN FUTURES

Indonesias evolution could drive the Southeast Asian security environment in either of two directions. A successful democratic transition in Indonesiato the extent that the Jakarta government retains the benign orientation toward Indonesias neighbors established under Suhartowould be factor of stability in Southeast Asia. It could lead to the reconstruction of a Southeast Asian security system grounded on democratic political principles. A stable Southeast Asia, in turn, would translate into reduced opportunities for potential Chinese hegemonism and, by the same token, could facilitate Chinas emergence as a more powerful state without destabilizing the regional balance of power. How Indonesia handles the tensions arising from ethnic and religious diversity, human rights, and political participation could also provide a model for other ethnically and religiously diverse countries in Southeast Asia and beyond. In its foreign policy orientation, a democratic Indonesia could be expected to continue to play the role of the good international citizen, seeking a stable international order and strong relations with its major economic partners and with neighboring ASEAN states.1 For the United States, a stable democratic Indonesia would offer better prospects for bilateral and multilateral cooperation, particularly full normalization of military-to______________

1 Anthony L. Smith points out the elements of continuity in Indonesian foreign policy

from Suharto to Wahid, in Indonesias Foreign Policy Under Abdurrahman Wahid: Radical or Status Quo State? Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol. 22, No. 3, December 2000. Some of these core elements would continue to shape the direction of a democratic Indonesian governments foreign policy.

77

78

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

military relations, by reducing the salience of human rights concerns in the bilateral relationship. That said, a common commitment to liberal democracy does not preclude conflicting interests. Politics in a democratic Indonesiato the extent that it accommodates nationalist or anti-Western forces, for instancecould well drive Indonesian policy in directions that the United States might find uncomfortable.2 The downside scenariospolitical deterioration, a return to authoritarian or military rule or, in the worst-case scenario, disintegration would drive the regional security environment in the opposite direction. Southeast Asia would become more chaotic and unstable, less inviting for investment and more prone to capital flight, and more vulnerable to a bid for regional domination by a rising China. The likely consequences of some possible scenarios are sketched in Table 8.1. Of the possible downside scenarios, a return to authoritarian or military rule could have the least severe consequences, from the standpoint of regional stability. An authoritarian or military government would likely be inward oriented, preoccupied with issues of domestic stability, and supportive of the regional status quo. The emergence of an authoritarian or military regime would not foreclose an eventual return to a democratic civilian government, but probably not before a degree of stability was restored. A turn toward authoritarianism in Indonesia could provoke an adverse reaction by the United States, the European Union, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and other members of the international community concerned about political and human rights in Indonesia. If this were to occur, the government in Jakarta could seek countervailing alliances with other authoritarian states. Despite historic suspicions of

______________

2 The idea that Indonesia should forge a common front with other Asian powers in

contraposition to the West has always had currency in Indonesia. After his election, President Wahid proposed a Jakarta-Beijing-New Delhi axis, a concept he subsequently downplayed, but that some commentators interpreted at the time as a revival of Sukarnoist foreign policy principles.

Regional Consequences of Indonesian Futures

79

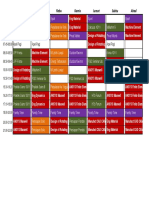

Table 8.1 Regional Consequences of Indonesian Scenarios

Scenario Democratic consolidation Regional Consequences Increased regional cooperation and stability Decreased opportunities for Chinese hegemonism Better prospects for security cooperation with the United States Strengthening of democratic tendencies in ASEAN Strengthening of authoritarian tendencies in ASEAN Decreased cooperation with U.S. and Western countries and institutions concerned with political and human rights; possible U.S. and international sanctions Possible rapprochement with China Alignment with radical Middle Eastern states and movements on international issues Support or encouragement of Islamic separatists in Mindanao and southern Thailand and of Islamic political forces in Malaysia Increased isolation of Singapore Anti-Western foreign policy orientation Increased potential for intervention by outside powers Increased refugee flows Increased piracy and transnational crime Severe regional economic dislocation Diminished effectiveness of ASEAN

Return to authoritarian or military rule

Radical Islamic influence

Disintegration

Beijings intentions, an authoritarian Indonesian regime may find compelling reasons for a rapprochement with China. Such a development, in turn, could open insular Southeast Asia to expanded Chinese influence, isolate the Philippines, and put pressure on Singapore to abandon its cooperative security relationship with the United States. It can also be expected that a military regime would be supported by most of the other ASEAN states, which are likely to be more concerned about stability than democracy in Indonesia. Some say that the region would secretly welcome it, especially if it stops disintegration and the sense of disorder in Jakarta and other major cities. Therefore, sanctions or pressure by the United States and other extraregional powers on Jakarta for a rapid return to democracy

80

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

would not be supported by regional states and could widen cleavages between the United States and ASEAN as a whole. A government in Jakarta dominated or influenced by radical Islamic elements would be far more disruptive of regional and international security and stability than the preceding scenario. Indonesia could be expected to draw closer to radical states and movements in the Middle East and join the forces opposing an Israeli/Palestinian peace agreement, the sanctions on Iraq, and the U.S. and Western presence in the Persian Gulf. Regionally, Jakarta could become a focus for the export of Islamic radicalism to the rest of Southeast Asia. An Islamic upsurge in Indonesia would encourage separatists in Mindanao and the southern Philippines, and could have a significant impact on Malaysia, where the Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS) has made inroads in traditional strongholds of the ruling United Malay National Organization (UMNO). The political system in place in Malaysia over the last 30 yearsa multiethnic coalition dominated by UMNOis under pressure as the result of the generational and political divisions manifested in the downfall, trial, and imprisonment of former Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim. This system could find itself under renewed assault by a surging PAS aligned with rising Islamic political forces in Indonesia. An alignment of Islamic parties and forces in Indonesia and Malaysia would be unsettling to the ethnic Chinese in both countries and to the city-state of Singapore. Singapore, wedged between these two Malay-majority countries and dependent on international trade for its economic survival, would find political instability and, in particular, ethno-religious conflict in its two immediate neighbors threatening. The Singaporeans are very much aware of the need to work with friendly countries to deal with threats to regional stability. At the same time, they are also aware of the limits of their influence, particularly in dealing with Indonesias enormous problems, and of the danger that any perceived intervention in Indonesian affairs could backfire by stoking Indonesian nationalism and anti-Chinese sentiments.3 ______________

3 Discussions with Singaporean government officials and defense analysts, Singapore,

February 2000.

Regional Consequences of Indonesian Futures

81

Indonesian disintegration would have severe humanitarian and economic consequences. First, one can assume that disintegration would be accompanied by large-scale violence in the Indonesian archipelago. There would be increased refugee flows, probably to Malaysia, Singapore, and Australia. An increase in piracy and transnational crime can be expected, brought about by economic dislocation and the breakdown in law and order. There would be few, if any prospects of the return of investment capital to Indonesia, and the rest of the regioneven well-ordered economies like Singaporewould suffer by association. Progress toward the development of a serious ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) would slow, as would the integration and rationalization of transport and infrastructure in the region. A deteriorating regional environment could also place at risk Philippine democracy, which steadily strengthened after the fall of the Marcos regime in 1986. Since then, there were three successive democratic presidential elections, democratic civilian control of the military was strengthened, and former military coup-makers and guerrillas alike were incorporated into the political system. Despite the impressive achievements of Filipino democracy, strong political and economic threats to stability remain. After his abortive impeachment on bribery charges, Estrada was driven from office in January 2001 by a military-backed popular uprising. The new government of President Macapagal Arroyo has to contend with significant Communist and Islamic insurgencies and the disaffection of Estradas supporters.4 Instability or disintegration would strengthen centrifugal forces elsewhere in Southeast Asia. The impact of the emergence of ministates in the former space of Indonesia could be especially threatening to regional states confronted by ethnic and religious divisions. As Indonesians point out, the rebellion in Aceh, although deriving from local sources, is not an isolated phenomenon. It is linked to a series of Muslim insurgencies of varying degrees of intensity, from southern Thailand to the southern Philippines. ______________

4 As of the beginning of February 2001, Estrada maintained that he was still the legiti-

mate president of the Philippines. Estrada is believed to retain substantial support among the poor, who constituted his core constituency in the 1998 election.

82

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

Muslim separatists in the Philippines are believed to maintain links with fundamentalist Islamic organizations in a number of other countries, including Pakistan, Egypt, and Afghanistan, and to have developed regional networks with radicals in Malaysia and insurgents in Aceh and southern Thailand.5 Thai authorities believe that Muslim separatists in southern Thailand received backing from Islamic militants in Malaysia, with the sanction of the ruling Islamic Party (PAS) in the province of Kelantan.6 Malaysias role vis--vis Muslim separatism in the Philippines and Thailand is difficult to pin down. The Malaysian External Intelligence Organization, which operates out of the Prime Ministers office, runs a serious intelligence operation from Sabah, maintaining links through Muslim groups anchored in the immigrant Malay community and the Melanau Muslim coastal people, to Philippine Muslim rebel groups. These go back to the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) links in Sabah during the 1970s. The extent to which Malaysia has it within its power to cut off support to the Muslim separatists in the Philippines is problematic. Turning against coreligionists in the southern Philippines is unpopular in UMNO circles, and Kuala Lumpur resents Manila inability to abandon territorial claims to Sabah. On the other hand, brazen kidnappings of visiting tourists in Sabah by Abu Sayyaf rebels infuriated the Malaysian government and led to shakeouts in the Sabah intelligence operation. 7 There are well-established arms pipelines from Cambodia through Thailand and Malaysia that serve Muslim insurgents in Aceh and Mindanao, the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka, and Sikh separatists in India. The Patani United Liberation Organization (PULO), a Muslim separatist organization in southern Thailand, is reportedly involved in arms smuggling to the Acehnese guerrillas. 8 Muslim insurgencies in Aceh, Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago, and southern Thailand derive sustenance from the socioeconomic ______________

5 See The Moro Insurgency, in Chapter Nine. 6 See Muslim Separatism in Southern Thailand, in Chapter Nine. 7 Personal communication from Dr. James Clad, January 2001. 8 Worse to come, Far Eastern Economic Review, July 29, 1999.

Regional Consequences of Indonesian Futures

83

and political grievances of the Muslim population in these countries, and some base their claims to legitimacy on the revival of the rights of Islamic states and sultanates that formerly held sway in their respective regions. Islamic separatists reject the legitimacy of the modern Southeast Asian states and the regional status quoan orientation that could make for unpredictable behavior toward regional and international institutions and norms, should they come to power in their areas. Rogue states in the area could interfere with fragile regional maritime commerce patterns. As Donald K. Emmerson noted, countries for which the Malacca Strait is a lifeline would wonder how an independent state of Aceh would regard freedom of navigation.9 The next chapter examines in greater detail separatist movements in the Philippines and Thailand.

______________

9 Donald K. Emmerson, Indonesias Eleventh Hour in Aceh, PacNet Newsletter , No.

49, December 17, 1999.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- 0000 Design by Optimization of An Axial-Flux Permanent-Magnet Synchronous MotorDocument5 pagini0000 Design by Optimization of An Axial-Flux Permanent-Magnet Synchronous MotorAnonymous hWj4HKIDOF100% (1)

- Principal Centred Leadership - Covey.ebsDocument6 paginiPrincipal Centred Leadership - Covey.ebsAbebe MenedoÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Speed of Trust: Based On The Book by Stephen MR CoveyDocument34 paginiThe Speed of Trust: Based On The Book by Stephen MR CoveyAnonymous hWj4HKIDOF100% (1)

- Meatless Days by Sara SuleriDocument6 paginiMeatless Days by Sara SuleriManahil FatimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Reality of Red Subversion The Recent Confirmation of Soviet Espionage in AmericaDocument15 paginiThe Reality of Red Subversion The Recent Confirmation of Soviet Espionage in Americawhitemaleandproud100% (3)

- 8 Theories of GlobalizationDocument12 pagini8 Theories of GlobalizationNarciso Ana Jenecel100% (3)

- New York Magazine - December 417 2023Document120 paginiNew York Magazine - December 417 2023shahrier.abirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Finite Element Programming With MATLABDocument58 paginiFinite Element Programming With MATLABbharathjoda100% (8)

- The Debating Handbook Grup BDocument4 paginiThe Debating Handbook Grup BSofyan EffendyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 15 Invaluable Laws of Growth Maxwell en 18403Document5 paginiThe 15 Invaluable Laws of Growth Maxwell en 18403Anonymous hWj4HKIDOF100% (1)

- Ok 00 - Casco v. Gimenez - Enrolled Bill TheoryDocument2 paginiOk 00 - Casco v. Gimenez - Enrolled Bill Theoryhabs_habonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lockwood David Social Integration and System Integration PDFDocument8 paginiLockwood David Social Integration and System Integration PDFEmerson93Încă nu există evaluări

- Schedule PlanDocument3 paginiSchedule PlanAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- 168Document104 pagini168emomoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tedy Kuswara: A StorytellerDocument1 paginăTedy Kuswara: A StorytellerAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASEN5022 Lecture 17Document24 paginiASEN5022 Lecture 17Bryan Brian LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 160612150559Document22 pagini160612150559Anonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhe OlogyDocument112 paginiRhe OlogyAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Odd Solutions Numerical 2009 1Document6 paginiOdd Solutions Numerical 2009 1Anonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- CE/ME504 Bibliography Fluid Dynamics Measurement BooksDocument1 paginăCE/ME504 Bibliography Fluid Dynamics Measurement BooksAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practic Te 02Document37 paginiPractic Te 02Anonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jadwal Juli - Oktober 2016 HarianDocument1 paginăJadwal Juli - Oktober 2016 HarianAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jadwal Persiapan S2 v2Document1 paginăJadwal Persiapan S2 v2Anonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matlab FemDocument45 paginiMatlab Femsohailrao100% (3)

- Jadwal Juli - Oktober 2016 HarianDocument1 paginăJadwal Juli - Oktober 2016 HarianAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macromechanical Analysis of a Lamina Exercise SetDocument12 paginiMacromechanical Analysis of a Lamina Exercise SetAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Finite Element Analysis: Understanding 1D Rods and 2D TrussesDocument34 paginiFinite Element Analysis: Understanding 1D Rods and 2D TrussesAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- E6 43 07 04Document18 paginiE6 43 07 04Anonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hossein Rideout KrougDocument9 paginiHossein Rideout KrougSri SaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- SLC - C and Data StructureDocument117 paginiSLC - C and Data StructuremahasiswaITÎncă nu există evaluări

- AjhizatDocument175 paginiAjhizatquranic_studyÎncă nu există evaluări

- AE Forces & Vector Calculus ReviewDocument8 paginiAE Forces & Vector Calculus ReviewAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3241 Final ReviewDocument56 pagini3241 Final ReviewAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- COBEM2007-0877 A Bond Graph Approach To Modeling An Aeroelastic BeDocument10 paginiCOBEM2007-0877 A Bond Graph Approach To Modeling An Aeroelastic BeAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- A New Method Development in Time Domain Aeroelastic VibrationDocument14 paginiA New Method Development in Time Domain Aeroelastic VibrationAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vehicle Model and Estimation Models UsingDocument10 paginiVehicle Model and Estimation Models UsingAnonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soal Drilling Calculus 2Document6 paginiSoal Drilling Calculus 2Anonymous hWj4HKIDOFÎncă nu există evaluări

- How the 'Standard of Civilisation' Shaped Global PoliticsDocument17 paginiHow the 'Standard of Civilisation' Shaped Global PoliticsDanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainable Priciple SrioDocument5 paginiSustainable Priciple SrioSanthanaPrakashNagarajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vajiram and Ravi Books ListDocument3 paginiVajiram and Ravi Books Listvenkatsri1100% (1)

- NHC Safety Survey Report - FinalDocument18 paginiNHC Safety Survey Report - FinalBen SchachtmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender Affirmative Care ModelDocument6 paginiGender Affirmative Care ModelGender Spectrum0% (1)

- Gonzales Cannon August 8 IssueDocument34 paginiGonzales Cannon August 8 IssueGonzales CannonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gandhi The Voice of IndiaDocument6 paginiGandhi The Voice of Indiasuper duperÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rab Rab - December 2023Document5 paginiRab Rab - December 2023ArtdataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Military Review August 1967Document116 paginiMilitary Review August 1967mikle97Încă nu există evaluări

- Kashmir Studies Mcqs Comp - IFZA MUGHALDocument16 paginiKashmir Studies Mcqs Comp - IFZA MUGHALAmirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cyber Security and Citizen 2030 - Roundtable - of - 2019 - Covering - Letter - For - NCSC - 2019 - Dec - 26Document3 paginiCyber Security and Citizen 2030 - Roundtable - of - 2019 - Covering - Letter - For - NCSC - 2019 - Dec - 26Col Rakesh SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The French RevolutionDocument2 paginiThe French Revolutiontatecharlie48Încă nu există evaluări

- Peter Adamson Plainfield Electoral Board HearingDocument3 paginiPeter Adamson Plainfield Electoral Board HearingRyneDanielsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Covid Data SetDocument18 paginiCovid Data Setpriyangka dekaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catholic University of Eastern Africa: Department of Arts and Social SciencesDocument10 paginiCatholic University of Eastern Africa: Department of Arts and Social SciencesKOT DecidesÎncă nu există evaluări

- StereotypeDocument11 paginiStereotypeapi-439444920Încă nu există evaluări

- Alan Paton - Cry, The Beloved Country (Plangi, Tara Iubita)Document10 paginiAlan Paton - Cry, The Beloved Country (Plangi, Tara Iubita)simona_r20069969100% (1)

- (Way People Live) Keeley, Jennifer - The Way People Live - Life in The Hitler Youth (2000, Lucent Books)Document118 pagini(Way People Live) Keeley, Jennifer - The Way People Live - Life in The Hitler Youth (2000, Lucent Books)Ciprian CipÎncă nu există evaluări

- File 1662629170Document180 paginiFile 1662629170La IrenicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PAC-Final CommuniqueDocument4 paginiPAC-Final CommuniqueMalawi2014Încă nu există evaluări

- Queer TheoryDocument22 paginiQueer TheoryKossmia100% (1)

- US and Soviet Global Competition From 1945-1991: The Cold WarDocument5 paginiUS and Soviet Global Competition From 1945-1991: The Cold WarAlejandro CoronaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aadhaar BFD Api 1 6Document4 paginiAadhaar BFD Api 1 6SudhakarÎncă nu există evaluări