Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Extensions of Time

Încărcat de

Hoang Vien DuDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Extensions of Time

Încărcat de

Hoang Vien DuDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Extensions of time

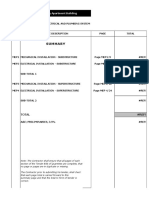

Summary Extensions of time are awarded to contractors who have committed to completing works by a certain date, but have been prevented from doing so by events for which the other party has agreed to take responsibility. Such events may arise from a neutral cause, such as exceptionally adverse weather conditions, or from a cause over which the employer has control, for example, instructions to undertake additional works. The only purpose for issuing extensions of time is to relieve the contractor of the imposition of delay damages (usually liquidated damages) for the period of the delay to completion. The calculation of the reimbursement of any additional costs arising out of the delay is completely separate and is not dependent on the extension of time calculation. Progressing the claim Triggering the extension of time mechanism Notification under the contract Most standard forms of contract require the contractor to submit to the representative of the other party notices of actual or anticipated delay as soon as the contractor becomes aware of any delay. Failure to provide such notices will not usually prevent the contractor from being granted an extension of time, unless clear words to that effect are used in the contract conditions. However, failure to provide such notices is a breach of contract that may entitle the other party to recover damages-for example, if the failure to provide such notices deprives the other party of an opportunity to mitigate the delay. The surveyor should therefore check that proper notices have been given specifying the circumstances, as soon as it became or should reasonably have become apparent that progress of the works, in whole or part, would be or had been affected by the stated event. There is generally not a contractually prescribed form for such a notice. A statement during a meeting that is subsequently minuted may suffice, but an oral statement at a meeting is not a notice in writing, which is usually required. Therefore it is generally necessary to send separate written notification of delay even if the matter has been discussed at a meeting. The purpose of the notice is to put the other party on notice that the circumstances in question were or would be likely to cause the contractor to suffer delay for which it would be entitled to an extension of time under the terms of the contract. Relevant cases (to be found in the Key cases section) with regard to notification under the contract are: City Inn Ltd v Shepherd Construction Ltd [2003] BLR 468 and Multiplex Constructions (UK) Limited v Honeywell Conctrol Systems Limited (No 2) [2007] EWHC 447 (TCC) . Initial response to the contractor In the event of an apparently valid claim being submitted, it is for the claim assessor to carry out the following, as required by the contract concerned: identify the claimed circumstances as notified; determine the circumstances actually causing the events on site; evaluate the effects on resources, including determining whether the effects are too remote from the cause; ascertain or determine the financial evaluation; and report on the claim.

In ascertaining loss or expense, or the amount of delay, the claim assessor should seek to obtain as much evidential demonstration as possible that the loss or delay in question has in fact been suffered. Often, even following an analysis of all available information, there may be some doubt. In such cases, if the claim assessor is satisfied that he or she has all available information, and is satisfied that it is not the contractor's fault that any further information is not available, the assessor should proceed either to include the amount in the next interim valuation (for loss and expense), or grant an extension of time, if there is a higher chance than not that the loss or delay has in fact been incurred (see Ascon Contracting Ltd v Alfred McAlpine Construction Isle of Man Ltd [1999] 66 ConLR 119 in Key cases, and paragraph 4.2.2.3 of The Surveyor's Construction Handbook). Design team action and records The architect or engineer is responsible for administering a contract so as to permit the contractor effectively to execute the works. Such post-contract action includes: programming the timely supply of information or variations in line with the contractor's applications; limiting variations to essential matters; giving early sound consideration to requests made by the contractor for additional information or monies; having a sound knowledge of progress and events on site; and providing a proper and full valuation of variations.

It is also the responsibility of the architect or engineer to instruct on and ensure the sound maintenance of project records of relevant issues, and review of the same, and to chair site progress meetings. As soon as the architect or engineer becomes aware that the contractor may become entitled to reimbursement of loss or expense, or to an extension of time, he or she should review the records that are being kept in order to be sure that they will enable an accurate ascertainment of the loss or expense, or delay, to be made. If it becomes necessary to instruct the contractor to keep additional records, this instruction should be issued as soon as possible (see paragraph 4.2.3.4 of The Surveyor's Construction Handbook). Requests for records, or to keep additional records, should be reasonable and relatively easy for the contractor to effect. Instructions for the contractor to collate and analyse information in a complex and time-consuming way could involve the client in additional liabilities. Detailed consideration of the claim It is important that a claim is not pre-judged prior to a consideration of the facts and circumstances. In the event of an apparently valid claim being submitted, the claim assessor should perform the following, as required by the relevant contract: identify the claimed circumstances as notified; determine the circumstances actually causing the events on site; evaluate the effects, or likely effects, on resources, including determining whether or not the effects are too remote from the cause (see explanation of 'remoteness' in the chapter on Loss and expense); assess the delay, or likely delay; and report on the claim.

In assessing the amount of delay, the assessor should seek to obtain appropriate evidential records to demonstrate that the delay in question has in fact been suffered for the reasons claimed. Often, even following an analysis of all available information, there may be some doubt. In such cases, if the claim assessor is satisfied that he or she does in fact have all available information, and that it is not the contractor's fault that any necessary information is not available, then he or she should proceed to grant

an extension of time if there is a higher chance than not that the delay was in fact incurred for the reasons claimed (see Ascon Construction Ltd v Alfred McAlpine Construction Isle of Man Ltd [1999] 66 ConLR 119 in Key cases). Having raised queries and requests for information, and given due time for the receipt of the same, the claim assessor may conclude the assessment on the basis of data to hand. Once records have been assembled and listed, the consideration of the claim may be progressed in line with the following checklist: contractor's issue of notice;

Check that a proper notice was given to the architect or engineer, specifying the circumstances, as soon as it became (or should reasonably have become) apparent that progress of the works, in whole or part, would be, or had been, affected by the stated event. There is generally no contractually prescribed form for such a notice. A statement during a meeting that is subsequently minuted will usually suffice. The issue is whether the client was deemed to have been put on notice that the circumstances were or would be likely to cause the contractor to suffer loss or expense, or delay, for which it would be entitled to reimbursement, or an extension of time, under the terms of the contract. heads of claim; check to see that the circumstances or events forming the heads of claim are covered by the contract; establish the date on which the architect or engineer was originally advised of the facts and circumstances now claimed by the contractor as causing loss and expense or delay (as well as establishing that the issues are the same as in the original notice); determine the key dates and events regarding the flow of additional data or other heads of claim (prepare a list of dates and events); for claims based on late information, ascertain the planned date on which the instruction or information requested should have been given to the contractor, the date on which it was actually given to the contractor, and when, in reality, it was necessary for the contractor to receive it, having regard to the progress of the works; establish the effects of the event on site labour, plant resources and progress on site (other than preliminaries). In particular, consider the following points: 1.when was the work due to take place? 2.when did the work take place? 3.what was the general effect on resources and progress on site? 4.what was the progress, at the time, of the other operations? Was the contractor already in delay for other reasons? Was this event the dominant cause of delay? 5.was unavoidable disruption or prolongation caused? 6.was regular progress affected? 7.was there a material (i.e., not trivial) effect on progress? 8.were the circumstances compounded by other problems, such as inclement weather? 9.were all reasonable measures taken by the contractor to mitigate the effects on site? Was notice of such intentions given to the architect or engineer? 10.are there ramifications on the critical path, other trades or other elements of the works? 11.a statement setting down the history of tasks on site will often be helpful (prepare a list of key dates and events); 12.how have labour and plant levels varied or been affected? 13.do records support the claimed circumstances? take a view, with the architect or engineer, of the effect on resources in terms of additional resources in quantum and weeks, days or hours or other priceable 'quantities', including abatements for the contractor's own problems, according to the 'but for' test set out above; ensure that there is no duplication with final account items; and

ensure that the effects are not too remote in law from the cause. effect on preliminaries items; identify whether items of a preliminaries nature have been affected; identify what, if any, extensions of time have been awarded for the specific circumstances in consideration. financial evaluation the effect on resources should be set out in detail; check to see whether the sums are recoverable elsewhere within the contract (for example, through variations, dayworks or an increased percentage recovery of overheads due to variations paid at rates inclusive of such); check to see whether loss or expense or delay has actually been incurred. Inspect wage sheets, revised plant hire agreements or additional payments made to sub-contractors, as well as records of standing time or overtime, and the like; check to see whether financial and record information has been provided as requested; check to see whether documentation and information has been provided by the contractor as soon as reasonably possible, and that the contractor has not delayed the evaluation of the claim; determine actual cost for the ascertainment of the claim (for example, wage sheets, hire charge or assessment). All costs should be exclusive of any profit or on-costs and should be after any discount has been deducted; finance charges should be evaluated from the date that the loss was incurred to the date on which payment was made (or is due to be made), less any period of delay caused by the contractor's own neglect. See F. G. Minter v Welsh Health Technical Services Organisation [1980] CA 13 BLR 1; alternatively, interest may be payable under the terms of the contract or under the provisions of the Late Payment of Commercial Debts (Interest) Act 1998. However, it is incumbent on the claim assessor to ensure that there is no duplication.

Retrospective delay analysis Main points The assessment for an extension of time must be supported by some form of analysis. The extent of such analysis may depend on factors such as the nature of the delaying event, the complexity of the project, and whether the submission relates to a simple notification of a likely delay to the architect or demonstration of delay in a more formal arena. Delay analysis is increasing in importance in the UK, with many surveyors identifying the need for a more detailed analysis than has hitherto been the norm. Surveyors, architects and engineers should take note of a number of important recent judgments when conducting such analyses. These are noted in the Key cases section and considered in some detail below. Importance of logical assessment Those responsible for analysing delay need to conduct a proper retrospective delay analysis. It is no longer acceptable (if it ever was) to award an extension of time or assess prolongation costs based on an impressionistic view formed from a comparison of simple bar charts. This principle was highlighted by the case of John Barker Construction Ltd v London Portman Hotels Ltd [1996], where the judge held that the effect of the architect making an impressionistic, rather than a calculated and logical, assessment of the contractor's entitlement to an extension of time, was to introduce a fundamental flaw into his assessment. The architect's award was therefore disregarded by the court, which used the contractor's own delay analysis to determine the contractor's entitlement to an extension of time. It is also important not to get too carried away with the delay analysis process. In Skanska Construction UK Ltd (Formerly Kvaerner Construction Ltd) v Egger (Barony) Ltd [2004] EWHC 1748 (TCC) a delay analyst who had been called al an expert witness was criticised by the judge for having prepared a report

of some hundreds of page, supported by 240 charts, but having undertaken inadequate research and checking of the facts. Ownership of float The ownership of any float contained within a contractor's programme is a much debated issue and has been argued about for many years. The case of Ascon Contracting Ltd v Alfred McAlpine Construction Isle of Man Ltd [1999] touched on the issue of float and provided some useful guidance on delay analysis, as well as illustrating the difficulties faced by a main contractor when trying to pin the blame for project delay onto its subcontractors. Concurrent delays The following text is derived from an opinion prepared by Jonathan Lewis, a barrister at 9 Stone Buildings. It has been subsequently edited and is included here with his kind permission. Where a claim or certain claims for money are made under the contract, the starting point must be to consider the terms of the clauses relied upon under the contract. The meaning of the clauses may be determinative of the approach to apply to causation, without any sophisticated analysis of the principles of causation, even if there is more than one competing cause of delay. However (more usually), the meaning of the relevant clauses may not answer the question as to which approach should be applied. In law, a number of approaches to causation have been suggested. In the context of apportioning loss arising out of competing causes, Keating on Building Contracts (see Further information for full details of this publication)suggests four possible approaches. The Devlin approach. If a breach of contract is one of two causes of a loss, with both causes cooperating and both of approximately equal efficacy, then the breach is sufficient to carry judgment for the loss (Heskell v Continental Express Ltd [1950], 1 All ER 1033 per Devlin J). The dominant cause approach. If there are two causes, one the contractual responsibility of the defendant and the other the contractual responsibility of the claimant, then the claimant succeeds if he or she establishes that the cause for which the defendant is responsible is the effective, dominant cause. The question as to which cause is dominant is a question of fact, to be decided by applying commonsense standards. The burden of proof approach. The claimant must effectively prove that 'but for' the defendant's breach of contract, he or she would have suffered no loss. The tortious approach. The claimant recovers if the cause upon which he or she relies caused or materially contributed to the delay.

The 'burden of proof',or the 'but for' approach to causation has been generally rejected as the correct approach (see Galoo Ltd v Bright Grahame Murray in the Key cases section). The editors of Keating submit that the correct approach to apply in instances of concurrency in construction contracts is the dominant cause approach. The other approaches are rejected primarily because they fail to answer what is referred to as the 'obverse problem'. The obverse problem arises because of reciprocal claims made for the same delay. It is considered a nonsense for both the contractor and employer (or, for that matter, the main contractor and sub-contractor) to have valid cross-claims against each other for the same period of delay, each relying on a competing cause for delay. It is considered that the dominant cause approach avoids such a result. An analogy is drawn with insurance cases, which require the identification of the dominant cause by applying commonsense standards. The leading insurance case of this type is the decision of the House of Lords in Leyland Shipping Co Ltd v Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society Ltd. The dominant cause approach has also found favour in the opinions of Lords MacLean, Johnston and Drummon Young in the Scottish case of John Doyle Construction Ltd v Laing Management (Scotland)

Ltd. In this case the court's opinion was that the question of causation must be treated by 'the application of common sense to the logical principles of causation': John Holland Construction & Engineering Pty Ltd v Kvaerner RJ Brown Pty Ltd, BLR 84I per Byrne J.; Alexander v Cambridge Credit Corporation Ltd, (1987) 9 NSWLR 310; Leyland Shipping Company Ltd v Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society Ltd , [1918] AC 350, at 362 per Lord Dunedin. In this connection, it is frequently possible to say that an item of loss has been caused by a particular event notwithstanding that other events played a part in its occurrence. In such cases, if an event or events for which the employer is responsible can be described as the dominant cause of an item of loss, that will be sufficient to establish liability, notwithstanding the existence of other causes that are to some degree at least concurrent. That test is similar to that adopted by the House of Lords in Leyland Shipping Company Ltd v Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society Ltd. The dominant cause approach also found favour in the Court of Appeal in Midland Mainline Ltd and Others v Eagle Star Insurance Company Ltd [2004] EWCA Civ 1042 which involved compensation for losses following the Hatfield train crash. It is recognised that the dominant cause approach is very much an 'all or nothing approach' to causation. In other words, if Party A proves that Party B was the dominant cause of delay, its claim will succeed even though Party B might have proven that Party A was also culpable to an extent. Conversely, if Party A proves that Party B acted in breach of contract and was a cause of delay, or even that Party B was an equally effective but not dominant cause of delay, Party A may be left without a remedy and Party B will escape liability for its breach. It is possible to derive from the authorities two approaches alleviating the potential harshness of the dominant cause approach. The first is really a restatement of the Devlin approach set out above. The second is based on a willingness to apportion damages between the claimant and defendant in cases of concurrent causation where the claimant and defendant are both culpable. Restatement of the Devlin approach If a breach of contract is one of two causes, both co-operating and both of equal efficacy in causing loss to the claimant or referring party, then the party responsible for the breach is liable to the claimant or referring party for that loss. The contract-breaker is liable so long as his or her breach was 'an' effective cause of the loss: the court need not choose which cause was the most effective. This proposition restates the dicta of Devlin J in Heskell v Continental Express Ltd, an approach approved by the Court of Appeal in the more recent cases of Banque Keyser SA v Skandia (UK) Insurance [1990] 1 QB 665 and County Ltd and another v Girozentrale Securities [1996] 3 All ER 834. If the above approach is applied, it only requires Party A to prove that Party B was an effective cause of the delay. Party A does not need to prove that Party B was more effective than itself in causing delay. Accordingly, the claim assessor does not need to identify the dominant cause of delay, so long as he or she is satisfied that Party B was an effective cause of the delay. The apportionment of damages in cases of concurrent causation This approach requires the claim assessor to consider the respective potency of both parties' conduct to the overall delay and allocate the financial consequences depending on the respective potency. It is correct to state that the courts have historically tended to apply the principles of causation in an 'all or nothing' way. In the absence of statutory authority, the courts have declined to apportion damages as between two or more competing causes. The Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945 permits apportionment of loss by the reduction of the claimant's damages where he 'suffers damage as the result partly of his own fault and partly of the fault of any other person'. The Act only applies to claims in contract in certain exceptional cases. However, in recent cases determined by English courts, the court has apportioned damages in cases involving competing causes, even though in each case the Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act

1945 was held to have no application. (See Tennant Radiant Heat Ltd v Warrington Development Corporation in the Key cases section.) The case of Tennant was considered briefly by the Court of Appeal in Bank of Nova Scotia v Hellenic Mutual War Risks Association (Bermuda) Ltd [1990] 1 QB 818 at 904. The Court of Appeal did not disapprove of the decision, although May LJ said, obiter: 'Similarly, we think that the facts and circumstances of the present case are such that it can and should be easily distinguished from those in Tennant Radiant Heat Ltd v. Warrington Development Corporation [1988] 1 E.G.L.R. 41, decided in this court on 16 December 1987. We merely add respectfully our view that the scope and extent of this last mentioned case would have to be a matter of substantial argument if the principle there applied were to arise for consideration in another case.' However, the case of Tennant was applied by HHJ Hicks QC in W Lamb Ltd (t/a The Premier Pump & Tank Co) v J Jarvis & Sons Plc. In fact, the judge considered that the decision in Tennant was binding upon him. There is also the dicta of Brandon J in the case of The Calliope, Carlsholm (owners) v Calliope (owners) [1970] 1 All ER 624 at 638, supporting the view that in principle, concurrent causation should be capable of being reflected in the apportionment of damage. More recently, in the Scottish case of John Doyle Construction Ltd v Laing Management (Scotland) Ltd the court's opinion was that even if it cannot be said that events for which the employer is responsible are the dominant cause of the loss, it may be possible to apportion the loss between the causes for which the employer is responsible and other causes. In such a case it is obviously necessary that the event or events for which the employer is responsible should be a material cause of the loss. Provided that condition is met, however, the judges were of opinion that apportionment of loss between the different causes is possible in an appropriate case. The Malmaison approach John Marrin QC, in an article on concurrent delay ((2002) 18 Const LJ at 436), submits that the correct approach is what has been described as the Malmaison approach, derived from the case of Henry Boot Construction (UK) Ltd v Malmaison Hotel (Manchester) Ltd. It is important to note that this case did not directly consider the correct approach to apply to causation in claims for money under the contract or for damages for breach of contract in cases where the causes of delay were concurrent. In the Malmaisoncase, Dyson J (as he then was) determined an appeal relating to a dispute on the pleadings in an arbitration as to the extent of the inquiry which the arbitrator was entitled to undertake to resolve one of the contractor's extension of time claims. The judge recorded that it was common ground between the parties that if there were two concurrent causes of delay, one a 'relevant event' (as defined in a standard form contract) and the other not, then the contractor would be entitled to an extension of time for the period of delay caused by the relevant event, notwithstanding the concurrent effect of the other event. A simple example was given (at 37, para. 13): 'If no work is possible on site for a week not only because of exceptionally inclement weather (a relevant event), but also because the contractor has a shortage of labour (not a relevant event), and if the failure to work during that week is likely to delay the works beyond the completion date by one week, then if he considers it fair and reasonable to do so, the architect is required to grant an extension of time of one week. He cannot refuse to do so on grounds that the delay would have occurred in any event by reason of the shortage of labour.' The suggested rationale for this approach is that it does no more than reflect the allocation of risk agreed upon by the parties when they entered into their contract. The suggestion is that, in allocating risks as between themselves, the parties may be taken, first, to have recognised that any one delay or period of delay might well be attributable to more than one cause and, secondly, to have agreed, nevertheless, that provided that one of those causes affords grounds for relief under the contract, then the contractor should

have his relief. (See also the case of Royal Brompton Hospital NHS Trust v Hammond (No. 7) [2001] 76 Con LR 148, QBD (TCC) per HHJ Seymour.) The following points might be made in relation to the article by John Marrinand the Malmaison approach. Although doubts are expressed about the dominant cause approach, it is thought that this is in the context of a contractor's rights to extensions of time, rather than causation generally. Even if the Malmaison approach is applied and the sub-contractor is entitled to an extension of time, notwithstanding concurrent causes of delay, it does not follow that the sub-contractor should be entitled to any compensation for the period of the extension. This is recognised in the Delay and Disruption Protocolpublished by the Society of Construction Law. The Protocol suggests that the contractor should not be entitled to any compensation unless it can separate out additional costs caused by the employer's delay from those caused by its own delay. This gives rise to the question of what approach should be taken to causation in determining a sub-contractor's money claim for prolongation under the contract. The Protocol does not expressly deal with this issue, but from its formulation of the contractor's entitlement, it appears to advocate the 'but for' test. In other words, unless the sub-contractor can prove that but for the delay caused by the contractor it would not have incurred additional costs, its claim for compensation will fail. The suggested rationale for the Malmaison approach is that the parties have agreed to allocate the risk, in the knowledge that any one period of delay might be attributable to more than one cause. It is submitted that this rationale is highly questionable. It is difficult to see why (or how) the parties should be taken to have allocated the risk, in circumstances where it is conceivable that both the contractor's claim for prolongation and the passing down of liquidated damages might fail because of the sub-contractor's entitlement to an extension of time. A sub-contractor's claim for compensation will also fail, unless it can prove that its loss and damage was caused exclusively by the contractor's delay, as opposed to its own. In addition, this scenario potentially gives rise once again to the obverse problem. Records Delay analyses, particularly when undertaken retrospectively are highly dependant on the availability of contemporaneous records and therefore preparation should be carefully managed by those administrating contracts from the commencement of each project. Most contractors maintain various contemporary records on construction projects as a matter of policy, as a management tool, because of contract requirements and to comply with statutory duty. Many of these record the progress of the works and what in the event occurred. These types of record include: progress meeting records; programme progress updates; short-term programmes and updates; marked-up drawings; progress photographs; general correspondence; concrete-pour records; daily site diaries and labour allocation sheets; general meeting minutes; and subcontractors' formal handover sheets.

In practice many of these records contain insufficient detail, are inaccurate or incomplete, and in some cases not kept at all. The quality and detail of the records are likely to vary considerably for different sections and time periods of the works and it is not unusual to find that the client's team have made no formal requests for records required under the contract nor for that matter a formal complaint when they do not appear. What is often seen is that record keeping tends to improve as the risk of a dispute increases with the parties looking a little more closely at the terms of the contract. The importance of keeping adequate and appropriate records cannot be overly emphasised.

Carrying out a delay analysis There are five main delay analysis techniques: as-planned v as-built; as-planned impacted; collapsed as-built; windows analysis; time impact analysis.

The as-planned v as-built is a simple comparison between the planned programme and the as-built programme. It is therefore a simple graphical comparison between what was planned to happen and what in the event actually did happen. The as-planned impacted method operates by adding or 'impacting' the claimed delaying events onto the planned programme. By adjusting the programme to take account of the effect of these events a revised programme is produced indicating their impact. The collapsed as-built involves removing the claimed delaying events from the as-built programme causing it to become shorter or to 'collapse'. The aim is to produce a programme which reflects what would have happened 'but for' the effects of the delaying events. Windows analysis breaks the works into discrete periods of time or 'windows'. By utilising contemporaneous progress information the status of the progress achieved in each window can be determined and explanations sought. Time impact analysis is similar to the windows analysis but rather than looking at delays within defined windows of time the actual timing and duration of the delaying event forms the period for analysis. Which technique should be used will be dependent on many factors including whether the delays are being considered during the course of the works 'prospectively' or retrospectively; the terms of the contract; the information available; the nature of the work; and the amount in dispute. It must be emphasised that all of the above techniques attract a certain amount of criticism and it is likely that they will produce differing results. With the exception of the as-planned v as-built, the above methods rely on the technique known as critical path analysis which brings with it problems associated with the need for certainty and possible theoretical and deterministic results. The use of critical path based software often results in the delay analyst concentrating more on the manipulation of the software and generation of voluminous programme charts than a review of the factual evidence. Whichever method is used to analyse delay it must be robust and produce a result that accords with common sense and the factual evidence. Concluding the evaluation Having raised queries and made requests for information, and given due time for the receipt of the same, the claim assessor may conclude the evaluation on the basis of data to hand. The burden of proof remains with the contractor. The claim assessor cannot be expected to speculate some time after the event as to why, for example, additional resources were employed. This is particularly relevant where details that could have been supplied were not. In this respect, allegations must be substantiated and every opportunity should be given to ensure that facts are verified at the time. Wholly unsupported details and lump sums or claims valued on the basis of anticipated cost set against actual costs are not generally acceptable evidence of actual additional expense caused by events for

which the employer is responsible. In such circumstances, the claim assessor should determine an evaluation based on details to hand. Failure with regard to the timely or adequate provision of necessary information is justification for the claim assessor to complete the evaluation using only the information made available, in accordance with the conditions of the contract. It is also justification for deductions to be made to finance charges if the late information has delayed payment. Failure in this respect by the contractor may also lead to a refusal to pay such expense in cases where delay has genuinely prevented or substantially prejudiced the investigation of any claim by the claim assessor. However, it should be remembered that an adjudicator or arbitrator is usually given full powers to open up and review all opinions, decisions, certificates and so on. Therefore, if information is provided after the final account has been prepared, this must be considered by the claim assessor when advising the client on potential liabilities in any adjudication or arbitration. Having concluded the recommendation on the above basis, no further detailed review need be progressed until reasonable data is to hand. However, attempts at resolving disagreement over valuation of loss, expense or delay may be undertaken, bearing in mind the option of referring the dispute to adjudication or to arbitration. Recommendation and report Recommendation and report Few contracts require the contract administrator to provide the contractor with a detailed assessment of how the extension of time was assessed, but many employers will want to have a report on the reasons for the amendment to the completion date. The discipline of setting out reasons in a report can actually be very helpful in arriving at a considered and logical assessment. If a report on the claim is issued, it is suggested that it should contain the following, as appropriate: general comments and background information; a note of the contractual provisions under which the claim arises; a note of concurrent events on the site that might have a bearing on the claim (for example, observations on the contractor's performance on site; the quality and efficiency of the site organisation; difficulties with sub-contractors; shortages of labour, plant or materials; a reluctance to comply with instructions; or faulty workmanship); comments on each item of claim with regard to its validity or any prima facie errors it may contain; factual information and records used for personnel and items of plant, and a record of how the time of each on site was affected by the delay; in the case of disputed items, the reasons why it has not been possible to reach agreement with the contractor; and evaluation and recommendation.

The following may usefully be attached as appendices: an abstract of the flow of information or instructions; an abstract of the events on site; and abstracts of records, diary entries and similar.

Further guidance on the award of extensions of time under Joint Contract Tribunal (JCT) contracts is provided in sections 2, 3 and 4 of the Society of Construction Law'sDelay and Disruption Protocol, and section 5 of Part 4 of the old Surveyors' Construction Handbook.

Payment of monies and granting of extensions Where it is apparent that monies are due, some payment should be made even if the total has not been fully calculated. Likewise, if it is apparent that some time is due to the contractor, an interim extension of time should be made, prior to a full calculation being carried out. In any event, an early response, without prejudice, should be issued to the contractor, setting out any prima facie errors and noting any additional information required. It is important that every effort is made to pay such losses or costs, or grant such extensions of time, as have been ascertained or determined, as soon as possible. This particularly applies to large claims with high interest rates or fast programmes. For loss and expense, having ascertained or determined the loss, the claim assessor should include an appropriate amount in the next valuation. The amount paid should be reviewed as and when significant new information is received, and when the claim assessor is satisfied that further payments are justified. For extensions of time, having assessed the delay, the claim assessor should recommend an appropriate extension to be granted. The amount of the extension should then be reviewed when significant new information is received. The proper, timely and professional consideration of claims reduces the risk of a major dispute arising. For loss and expense, values should be reduced in subsequent valuations where they are shown to have been previously assessed at too high a level. Any delays in reducing amounts included in valuations will only exacerbate the problem. However, valuation reductions are always difficult and should be avoided wherever possible. The contractor has a legitimate interest in the stability of amounts included in the interim valuations, as it will probably use figures in the valuations as a basis for payment of subcontractors and suppliers. Where a contractor is late in supplying information, appropriate deductions from finance charges should be made. With regard to extensions of time, many standard forms of contract do not allow the contract administrator to review the entitlement to an extension of time downwards. Extensions should therefore not be granted, for example, on the promise of further evidential information being provided. Key cases Multiplex Constructions (UK) Limited v Honeywell Control Systems Limited (No 2) [2007] EWHC 447 (TCC) Honeywell had completed their works late on the Wembley National Stadium and Multiplex had deducted liquidated damages. Honeywell raised a number of legal arguments in their assertion that the extension of time mechanism was flawed or had failed and therefore time was at large. The judge started his analysis of the law with a review of existing case law and the making of 3 propositions 1. by the employer which are perfectly legitimate under a construction contract may still be characterised as prevention if those actions cause delay beyond the contractual completion date. 2. of prevention by an employer do not set time at large if the contract provides for extension of time in respect of those events. 3. so far as the extension of time clause is ambiguous, it should be construed in favour of the contractor. However, this proposition must be treated with care. In so far as an extension of time

is ambiguous the court should lean in favour of a construction which permits the contractor to recover appropriate extensions of time in respect of events causing delay. The key relevant points raised by Honeywell can be summarised as follows: 1. a true construction of a sub-contract there is no provision for Multiplex to grant an extension of time where the contractor issues a direction (as opposed to a variation) which delays the subcontractor. Therefore time is at large. The judge held that applying proposition 3 above the true construction of the sub-contract enabled Multiplex to grant an extension of time in these circumstances. Therefore time was not at large. 2. management of the contract had been such that the mechanism for granting an extension of time had broken down. Therefore no extension could be granted. Therefore time was at large. The judge held that the contract only required Honeywell to provide such details as were available to it. If Multiplex's management of the contract (and in particular their failure to provide updated programmes) prevented Honeywell from analysing the effects of events, that did not amount to a failure of the extension of time mechanism. Honeywell were only required to give as much information about the effects of the event as was possible in the circumstances. Therefore time was not at large. 3. contract imposed certain conditions that were conditions precedent to Honeywell's entitlement to an extension of time. If Honeywell failed to comply with these pre-conditions Multiplex were therefore prevented from granting an extension of time, therefore time was at large. Honeywell cited an Australian case in support of their position. The judge doubted that this represented English law. In any event the judge concluded that on a true interpretation of the sub-contract Honeywell were only required to provide such details as were available to it which, on their own evidence, Honeywell had done. 4. Subcontract stipulated that Honeywell's entitlement to an extension of time would be no greater than Multiplex's entitlement under the main contract. In settlement negotiations with their client Multiplex had agreed an absolute date for completion. Honeywell argued that the combined effect of this agreement between Multiplex and their client and the terms of the sub-contract restricted Multiplex's ability to grant an extension of time to Honeywell. Therefore time was at large. The judge concluded that Multiplex's settlement negotiations with their client were independent of Honeywell's entitlement under the sub-contract. The limitation in the sub-contract would not apply if Honeywell's entitlement to an extension of time was greater than the absolute date agreed between Multiplex and their client. Skanska Construction UK Limited (Formerly Kvaerner Construction Limited) v Egger (Barony) Limited [2004] EWHC 1748 (TCC) A large part of this case involved competing evidence from two eminent delay analysts. Of one analysis the judge said that it was a report of some hundreds of pages supported by 240 charts. It was a work of great industry incorporating the efforts of a team of assistants. However the judge concluded that the analyst was not entirely familiar with the details of his own report which was based on inadequate research and checking. John Doyle Construction Ltd v Laing Management (Scotland) Ltd [2004] ScotCS 141 (11 June 2004) The use of the dominant cause approach to delay analysis has been confirmed as the appropriate methodology to adopt by the Scottish case of John Doyle Construction Ltd v Laing Management. This case was heard in the Extra Division, Inner House, Court of Session by Lord Maclean, Lord Johnston, Lord Drummond Young on the 11th of June 2004. This case is important for three reasons:

Firstly this case confirms that global claims are acceptable where it is possible to identify a causal link between a package of events for which the employer is responsible and a package of additional costs. Secondly, this case confirms that if there are concurrent causes for a particular loss or package of losses that identification of the dominant cause of loss as one for which the employer is responsible will be sufficient to establish liability. Thirdly, this case confirms that where there are concurrent causes of loss and where it is not possible to establish the dominant cause of loss as one for which the employer is responsible, it may nevertheless be possible to apportion the loss between the causes for which the employer is responsible and other causes. Provided that the event for which the employer is responsible is a material cause of the loss the court confirmed that apportionment of loss between the different causes is possible in an appropriate case, such as where the causes of the loss are truly concurrent in the sense that they operate together at the same time to produce a single consequence. Therefore it is not open to the employer to dismiss all or part of a contractor's claim on the basis that there were (or may have been) elements of concurrent delay if the dominant cause of delay is one for which the employer is responsible. Also, a claim should not be dismissed solely on the basis that there are elements of the costs which have been calculated on a 'global basis'. The above case confirmed that a global claim should not be dismissed if there was a possibility of the claiming party being able to demonstrate chains of causation between individual causes and heads of loss, or of the claiming party being able to demonstrate that the dominant cause of the loss was the employer's responsibility, or of the claiming party being able to use the process of apportionment to divide the costs between the various causes. Midland Mainline Limited and Others v Eagle Star Insurance Company Limited [2004] EWCA Civ 1042 This case arose out of claims by train operating companies for losses sustained by track speed restrictions following the Hatfield train crash and the subsequent focus on corner gauge cracking. In this case the Court of Appeal had to determine whether the proximate cause of the losses was the imposition of speed restrictions by Railtrack (an event for which the train operating companies were insured) or corner gauge cracking resulting from wear and tear (an event for which the train operating companies were not insured). The Court of Appeal referred to Leyland Shipping Co Ltd v Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society Ltd and concluded that there can be more than one proximate cause of loss. In this case the Court of Appeal held that if they had to find one proximate cause of loss it would be the corner gauge cracking but that alternatively there were two proximate causes of the loss which were approximately equal in effectiveness without one of them being clearly more decisive than the other. Having found that corner gauge cracking was a proximate cause of the loss (either by itself or in common with the imposition of speed restrictions) the Court of Appeal applied this to the terms of the insurance policy and found in favour of Eagle Star. Henry Boot Construction (UK) Ltd v Malmaison Hotel (Manchester) Ltd [1999] 70 ConLR 32 This is a much quoted case relating to the evaluation of concurrent delay. In his judgement Judge Dyson referred to the fact that both parties agreed: '... if there are two concurrent causes of delay one of which is a relevant event and the other is not, then the contractor is entitled to an extension of time for the period of the delay caused by the relevant event notwithstanding the concurrent effect of the other event.'

This quotation is often misquoted as being a statement of the judge rather than a statement in the judgement - the judgement merely records the party's agreement. London Borough of Merton v Stanley Hugh Leach [1985] 32 BLR 51 This case is important in the following respects: it confirms that in exercising discretionary powers under a traditional Joint Contracts Tribunal (JCT) contract, the architect should not only exercise due care and skill, but also reach decisions fairly, holding the balance between the client and the contractor. (See also Sutcliffe v Thackrah [1974] 4 BLR 16 at 21); it confirms that the building owner under a traditional JCT contract (either directly or via the architect) is under a positive duty to do all things necessary to enable the contractor to carry out the work. (See also Holland Hannen & Cubitts v Welsh Health Technical Services Organisation [1983] 18 BLR 80 at 117); it confirms that a programme that highlights with milestones when information is required from the architect is sufficient to satisfy the JCT requirement for the contractor to ask for the information at a time that is neither unreasonably distant from nor unreasonably close to the date on which it is necessary to receive the same; under the JCT 63 conditions (which are similar in this regard to the conditions of JCT 98 (Standard Form of Building Contract With Quantities 1998), an application by the contractor is held not to be a condition precedent to the contractor's entitlement to an extension of time, but a breach of contract which the architect is entitled to take into account when making his or her assessment.

John Barker Construction Ltd v London Portman Hotel Ltd [1996] 83 BLR 31 This case is important because it emphasises the extent of analysis that a contract administrator must prepare when coming to a determination on extension of time entitlements. In this case, the claimant was claiming an extension of time for the full construction period from the respondents. The claimant had appointed a delay analyst who had prepared a detailed, logical analysis of the progress on site and reasons for the delay. The respondent's architect had made an impressionistic determination, albeit in good faith, for a shorter period. Mr Recorder Toulson QC said: '... in my judgment [the architect's] assessment of the extension of time due to the [claimants] was fundamentally flawed in a number of respects, namely: [the architect] did not carry out a logical analysis in a methodical way of the impact that the relevant matters had or were likely to have on [the claimant's] planned programme.He made an impressionistic, rather than a calculated assessment of the time which he thought was reasonable for the various items individually and overall (the [respondents] themselves were aware of the nature of [the architect's] assessment, but decided against having any more detailed analysis of [the claimant's] claim carried out unless and until there was litigation).[The architect] misapplied the contractual provisions... Because of his unfamiliarity with SMM7 [the standard method of measurement of building works] he did not pay sufficient attention to the content of the bills, which was vital in the case of a JCT contract with quantities.Where [the architect] allowed time for relevant events, the allowance which he made in important instances bore no logical or reasonable relation to the delay caused. I recognise that the assessment of a fair and reasonable extension involves an exercise of judgment, but that judgment must be fairly and rationally based.'

Ascon Contracting Ltd v Alfred McAlpine Construction Isle of Man Ltd [1999] 66 Con LR 119 In this case, the claimant had made a claim for an extension of time and for loss and expense. A number of the heads of claim were clearly valid, but the quality of evidence presented to prove cause and effect was very poor. HH Judge John Hicks QC nevertheless decided that if he was satisfied that there was an entitlement, he should assess the quantum on the basis of the evidence before him. Potential claimants should not take this case as an authority for justifying laziness. Numerous cases have demonstrated that a valid claim supported by high-quality contemporaneous records, properly analysed, will achieve much better results than one supported by poor evidence. Indeed, the ability to prove one's case is often the trigger for achieving a satisfactory settlement without the need for litigation. This case also contributes to the argument as to who owns the float in a programme. HH Judge Hicks said: 'Six sub-contractors, each responsible for a week's delay, will have caused no loss if there is a six-weeks' float. They are equally at fault, and equally share in the 'benefit'. If the float is only five weeks, so that completion is a week late, the same principle should operate; they are equally at fault, should equally share in the reduced 'benefit' and therefore equally in responsibility for the one week's loss. The allocation should not be in the gift of the main contractor.' Balfour Beatty Building Ltd v Chestermount Properties Ltd [1993] 32 ConLR 139 This case confirms that where a delaying event qualifying for an extension of time occurs during a period in which the contractor is already in culpable delay, a 'net' extension of time shall be granted so that the contract completion date is extended by a period comparable to the additional delay caused by the event. In this particular case, the contractor unsuccessfully argued that the new completion date should be fixed at a time after the occurrence of the delaying event, regardless of the existing culpable delay. Dodd v Churton [1897] 1 QB 562 This case is authority for the principle that an employer cannot enforce time provisions if he or she has been responsible for an act of prevention, unless the contract provides provisions for granting an extension of time. A variation instruction would, in the absence of contractual provision to the contrary, be an act of prevention. Fairweather v London Borough of Wandsworth [1987] 38 BLR 106 This case demonstrates the application of the 'dominant cause' approach to the determination of extensions of time and to the calculation of loss and expense. In this case, the contractor (Fairweather) was delayed, because the employer was late in giving possession of a small but critical area of the site. The dominant cause approach was applied to give the contractor an extension of time. However, during consideration of the assessment of additional cost, the court found that this delay caused only a small part of the contractor's actual prolongation costs. The majority of these costs were caused by reason of other events for which the contractor was responsible. City Inn Ltd v Shepherd Construction Ltd [2003] ScotCS 146 (20 May 2003) In this case, the contract contained a provision requiring the contractor (Shepherd Construction Ltd) to undertake certain formalities (including the provision of notices) if it formed the opinion that a delaying event had arisen. These formalities were contained in clause 13.8.1 of the contract. Clause 13.8.5 of the contract provided as follows:

'If the Contractor fails to comply with any one or more of the provisions of Clause 13.8.1, where the Architect has not dispensed with such compliance under Clause 13.8.4, the Contractor shall not be entitled to any extension of time under Clause 25.3.' A delaying event occurred, but Shepherd Construction failed to issue the necessary notices. Despite this failure, and the above clause, the architect awarded an extension of time of four weeks. This award was followed by an adjudication, in which the adjudicator allowed a further extension of time of five weeks. This action was brought by City Inn to reverse the above decisions and to claim its entitlement to liquidated damages. City Inn was successful both in the court of first instance and in the Court of Appeal. The arguments of Shepherd Construction were that firstly, clause 13.8.5 was a penalty clause, and secondly, clause 13.8.1 required Shepherd Construction to provide notices when they formed the opinion that a delay would result. As they had not formed such an opinion at the relevant time, they were not in breach of the clause. The courts found that failure to comply with clause 13.8.1 was not a breach of contract - it was an option which the contractor could choose to implement. The consequences of not implementing the procedure did not amount to liquidated damages and therefore were not subject to the test of penalties. The court also found that the interpretation of the clause as a whole required the contractor to apply its mind to the consequences of an instruction. It was not sufficient for the contractor to aver that it had not actually formed the opinion contemplated by the provision. Galoo Ltd v Bright Grahame Murray [1994] 1 WLR 1360, CA The defendants in this case were the auditors of the claimants. The audited accounts suggested that the claimants were profitable and had substantial assets. It was alleged by the claimants that a competent audit would have revealed that the two companies were unprofitable and worthless. The claimants argued that by reason of the auditor's breach of contract, they had suffered loss, because they continued to trade after they otherwise would have done. Glidewell LJ treated the claimants' argument on causation as an invitation to apply the 'but for' test. He rejected that test and in so doing, applied the dominant or effective cause approach. He said: 'The passages which I have cited....make it clear that if a breach of contract by a defendant is to be held to entitle the plaintiff to damages, it must first be held to have been an 'effective' or 'dominant' cause of his loss. How does the court decide whether the breach of duty was the cause of the loss or merely the occasion for the loss? The answer in my judgment is supplied by the Australian decisions to which I have referred, which I hold to represent the law of England as well as Australia, in relation to a breach of duty imposed on a defendant whether by contract or by tort in a situation analogous to a breach of contract. The answer in the end is "By the application of the court's common sense".' Leyland Shipping Co Ltd v Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society Ltd [1918] AC 350 In this case a ship was torpedoed by a German submarine and was subsequently taken to Le Havre in France for repair. The ship was badly damaged and was taking in a lot of water. While she was in the deep-water harbour, the ship was moved from one quay to another, for fear that the ship might sink and disrupt the activities of the Red Cross at that quay. The sea conditions were rough, though not exceptionally so. While being moved, the ship broke up and was lost. The question for the House of Lords was what caused the losses arising from the ship sinking. Was it the war action for which the owners were not insured, or the perils of the sea, for which the owners were insured? It was held that the ship sank because it was torpedoed, and that the losses were not recoverable from the insurers. Lord Shaw stated:

'Where various factors or causes are concurrent and one has to be selected, the matter is determined as one of fact, and the choice falls upon the one to which may variously be ascribed the qualities of reality, predominance, efficiency'. Tennant Radiant Heat Ltd v Warrington Development Corporation [1998] 1 EGLR 41, CA In this case, a landlord's damages against his lessees for breach of a repairing covenant (a strict obligation) were reduced by 90% because he as landlord had negligently failed to keep clear the drainage outlets of the roof. The landlord's failure was held to be a concurrent cause of the collapse of the roof, to which 90% of the total causation was assigned. W Lamb Ltd (t/a The Premier Pump and Tank Co) v J Jarvis and Sons plc (1998) 60 Con LR 1 In this case HHJ Hicks QC considered that the decision in Tennant was binding upon him. The facts of this case were that the defendant was the main contractor for the construction of a service station and the claimant was the sub-contractor for the design, supply and installation of fuel tanks, pipework and pump fittings. The claimant installed the pipes and thereafter there was evidence of leaks. The pipes were removed and replaced by the claimant under a supplemental agreement. The issue was whether the claimant or defendant should bear the cost of the remedial works. There was evidence of defective work by both the claimant and defendant, but nothing pointing clearly to either as the sole cause of any particular leak. The court (although invited to do so by the claimant) did not apply the dominant cause test, nor did it apply the 'but for' test to causation. The learned judge held that there was no rule of law preventing apportionment in the circumstances of that case. Further, although litigation about causation usually ended in a decision that only one cause was effective, this was not necessarily so as a matter of law. Frequently asked questions Why are extensions of time of benefit to the employer? If the employer delays the contractor then, in the absence of extension of time provisions, the employer is unable to deduct liquidated damages. Therefore by granting an extension of time in such circumstances the employer is protecting his right to deduct liquidated damages. When is time at large? Time is said to be 'at large' when there is no definite completion date. The contractor's only obligation is to complete the works within a reasonable time. This may either be where no completion date was agreed in the contract or where the employer has delayed the contractor and cannot extend the contract completion date. Do I have to do a delay analysis and how sophisticated does it have to be? If there is a dispute over the actual extent of delay caused the tribunal is likely to give more credence to a sophisticated delay analysis than to a superficial impressionistic appraisal. In many standard forms of contract the architect or engineer is appointed as an independent certifier to assess delay and grant an extension of time. In such a role it is not sufficient for the certifier to adopt a superficial impressionistic appraisal but must carry out a more sophisticated delay analysis.

If the contractor is late but does not delay the works because the employer is also late providing information is the contractor entitled to an extension of time? This is often referred to as concurrent causes of delay. Traditionally standard forms of contract have not addressed this scenario and therefore it has been up to the courts to determine whether an extension of time should be granted in such cases. As a result of this a body of inconsistent case law has developed and a number of inconsistent approaches have been adopted. Perhaps the most widely held view is that where the contract is silent on such matters an extension of time should be granted for the full delay if the delay caused by the employer is the dominant cause of delay to the project. However, if the dominant cause of delay is the delay caused by the contractor then no extension of time should be granted. Many employers now amend standard forms of contract to clarify whether an extension of time should be granted where there are concurrent causes of delay. In such cases the courts will interpret the intentions of the parties as set out in the contract. Is the employer entitled to use float in the contractor?s programme? There are many types of float in the programme. One type of float is attributed to activities that are not on the critical path. Another type of float may be an activity specific contingency. Yet another type of float may be whole project float where the contractor plans to finish the project before the contract completion date. If the employer causes a delay most standard forms of contract require the contractor to minimise the impact of that delay by re-structuring activities on site. Therefore the employer's delay will use the float in the non-critical activities without a detrimental impact on the completion date of the project. With regard to activity specific contingencies most delay analyses will involve an analysis and validation of the contractor's programme. If it is found that activities are unreasonably long (eg contain too much contingency) or are unreasonably optimistic then they will be adjusted accordingly. This author submits that the contractor is entitled to retain a reasonable amount of activity specific float by way of contingency which the employer is not entitled to use until after the risk for which the contingency has been allocated has either materialised or passed. With regard to whole project float there are two competing theories. For example if there are 3 weeks whole project float but the employer defers possession by 3 weeks. During construction events arise which delay the contractor by 3 weeks. On the one hand the employer's delay analysed in isolation has not caused any delay (it has only used up the float) and therefore no extension of time should be granted. On the other hand there is some case law to suggest that the benefit of such float ought to be apportioned equally across all of the various causes of delay. I represent a contractor who is claiming an extension of time. We have prepared a retrospective delay analysis based on the best information available. We accept that the records are not as comprehensive as they might be, but we are satisfied that they do If you have based your claim on the best evidence available then, subject to any contractual requirements as to record-keeping, you will be entitled to rely on that evidence as the basis for your claim. If you refer your claim to an adjudicator, the adjudicator will apply the 'balance of probabilities' test to the evidence before him. If the evidence available demonstrates that the cause of the delay was more probably than not one that entitles you to an extension of time, then the adjudicator will grant you this. However, a word of caution. This should not be used as an excuse for laziness. If better evidence is available, you will often be better off extracting and presenting that to the employer to support your claim, rather than adjudicating on inconclusive evidence.

Further information on extensions of time Resources Lowsley, S. and Linnett, C., About Time: Delay Analysis in Construction, RICS Books, 2006 (ISBN 1 84219 247 7) Birkby, G. and Brough, P., Construction Companion to Extensions of Time, RIBA Publications, London, 2002 (ISBN 1 85946 099 2). Egglestone, B., Liquidated Damages and Extensions of Time in Construction Contracts , Blackwell Science, Oxford, 1997 (ISBN 0 63204 213 3). Ramsey, V. and Furst, S., Keating on Building Contracts(7th edition), Sweet and Maxwell, London, 2001 (ISBN 0 42156 530 6). Society of Construction Law (SCL), Delay and Disruption Protocol, SCL, Wantage, 2002

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Project ManagementDocument25 paginiProject ManagementNdomaduÎncă nu există evaluări

- 08-11-24 M&e BQDocument6 pagini08-11-24 M&e BQHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fosroc Polyurea Brochure 120320Document7 paginiFosroc Polyurea Brochure 120320Hoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- OUM - MBA - Group 3 - 28nov22Document61 paginiOUM - MBA - Group 3 - 28nov22Hoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10ha Electrical Work BQ 20.11Document9 pagini10ha Electrical Work BQ 20.11Hoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handbook Safety PDFDocument219 paginiHandbook Safety PDFJia IdrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appendix To Tender (Main Contract Form)Document2 paginiAppendix To Tender (Main Contract Form)Hoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- MS471PT3 2003Document6 paginiMS471PT3 2003Hoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14 Remont I Obsluzhivanie DE12, T, TI, TISDocument169 pagini14 Remont I Obsluzhivanie DE12, T, TI, TISHoang Vien Du80% (5)

- SKL Showroom ModelDocument1 paginăSKL Showroom ModelHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Timber Door BreakdownDocument1 paginăTimber Door BreakdownHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Huafengdongli 495 4100 Series OperationmanualDocument73 paginiHuafengdongli 495 4100 Series OperationmanualHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Experience ReportDocument3 paginiNew Experience ReportHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amending Standard Form ContractsDocument10 paginiAmending Standard Form ContractsHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application Submission Requirements 1 Page Summary SheetDocument1 paginăApplication Submission Requirements 1 Page Summary SheetHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPD. Online Recording User GuideDocument15 paginiCPD. Online Recording User GuideHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- RICS Associate - Quick Reference GuideDocument5 paginiRICS Associate - Quick Reference GuideHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- BK Workshops Surgeries OctNov09Document8 paginiBK Workshops Surgeries OctNov09Hoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Xaydung360.Vn - Project Management PlanDocument15 paginiXaydung360.Vn - Project Management PlanHoang Vien Du100% (1)

- BOQ Luqa Gates Un-PricedDocument6 paginiBOQ Luqa Gates Un-PricedHoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Management E-BookDocument48 paginiProject Management E-BookadeelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Construction Cost EstimatesDocument123 paginiConstruction Cost EstimatesOddysseus5100% (15)

- MPM-003 100807Document3 paginiMPM-003 100807Hoang Vien DuÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Policy 555839668 1899087538702Document5 paginiPolicy 555839668 1899087538702utkarsh ambreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Customer StatementDocument18 paginiCustomer Statementmuhyideen6abdulganiyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lakshmi Narain College of Technology, (LNCT) Jabalpur: Rani Durgavati Vishwavidyalaya, JabalpurDocument51 paginiLakshmi Narain College of Technology, (LNCT) Jabalpur: Rani Durgavati Vishwavidyalaya, Jabalpurroshni raiÎncă nu există evaluări

- INDEMNITY INSURANCE COMPANY OF NORTH AMERICA v. FOODLINER, INC. ComplaintDocument6 paginiINDEMNITY INSURANCE COMPANY OF NORTH AMERICA v. FOODLINER, INC. ComplaintACELitigationWatchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compensation PackageDocument27 paginiCompensation PackagemysubicbayÎncă nu există evaluări

- B2B Assignment On Federated Insurance Case StudyDocument6 paginiB2B Assignment On Federated Insurance Case StudyJyoti PandeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delta Dental Plan BookletDocument36 paginiDelta Dental Plan BookletmecheeksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Announcement UNILEADDocument4 paginiAnnouncement UNILEADbila2010Încă nu există evaluări

- Romcab - Acatari - P2 - Appendix To Tender - Nr2 - Employer's RequirementsDocument42 paginiRomcab - Acatari - P2 - Appendix To Tender - Nr2 - Employer's RequirementsidlaurapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Best Procurement PracticesDocument13 paginiBest Procurement PracticesSolomon AppiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ranjit's United India Fire & General Insurance Companies LTDDocument42 paginiRanjit's United India Fire & General Insurance Companies LTDKristin SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vastoler, Soloman A. v. American Can Company, A Corporation and The Annuity Board of The American Can Company Retirement Plan For Salaried Employees, 700 F.2d 916, 3rd Cir. (1983)Document7 paginiVastoler, Soloman A. v. American Can Company, A Corporation and The Annuity Board of The American Can Company Retirement Plan For Salaried Employees, 700 F.2d 916, 3rd Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To File A Claim-For GSISDocument2 paginiHow To File A Claim-For GSISZainal Abidin AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Insurance: Name of MembersDocument32 paginiInsurance: Name of MembersabhijeetskupateÎncă nu există evaluări

- Predictive Analytics The Power To Predict Who Will Click, Buy, Lie, or DieDocument3 paginiPredictive Analytics The Power To Predict Who Will Click, Buy, Lie, or DieFizza ChÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anurag Gautam (Policy)Document1 paginăAnurag Gautam (Policy)Aravind AravindÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heather Clift Resume 2017Document3 paginiHeather Clift Resume 2017api-414335713Încă nu există evaluări

- SSPC SP3Document2 paginiSSPC SP3Jose AngelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Due Diligence ExerciseDocument6 paginiDue Diligence Exercisevrushaliubale21Încă nu există evaluări

- Bajaj Allianz General Insurance Company Ltd. Bajaj Allianz House, Airport Road, Yerawada, Pune - 411006 Group Personal Accident Policy ScheduleDocument2 paginiBajaj Allianz General Insurance Company Ltd. Bajaj Allianz House, Airport Road, Yerawada, Pune - 411006 Group Personal Accident Policy Schedulehari bharadwajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidance On StowawaysDocument38 paginiGuidance On Stowawaysanshul_sharma_5Încă nu există evaluări

- Project Report ON A Study On Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC)Document69 paginiProject Report ON A Study On Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC)Himanshu AggarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- State Life Insurance Corporation of PakistanDocument39 paginiState Life Insurance Corporation of PakistanAsad Mazhar50% (4)

- Agent Name & No Airtel Payments Bank LTD (11006207) Agent Contact No 8800688006Document2 paginiAgent Name & No Airtel Payments Bank LTD (11006207) Agent Contact No 8800688006Toufeeq AbrarÎncă nu există evaluări

- ManagementDocument25 paginiManagementShruti Yendhe100% (1)

- Ch10 Tutorials Intermed Acctg Acquisition and Disposition of PPEDocument6 paginiCh10 Tutorials Intermed Acctg Acquisition and Disposition of PPESarah GherdaouiÎncă nu există evaluări

- TAXATION Ver 2Document3 paginiTAXATION Ver 2coleenllb_usaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taxation I Syllabus - Chapters 1 13Document9 paginiTaxation I Syllabus - Chapters 1 13Christianne Jan Micubo EchemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lof and Scopic HistoryDocument22 paginiLof and Scopic HistoryBansal SunilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forrester Wave Document Output For Customer Communications Management 2009Document25 paginiForrester Wave Document Output For Customer Communications Management 2009DebrajÎncă nu există evaluări