Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

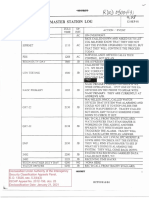

FO B2 Public Hearing 7-9-03 1 of 2 FDR - Tab 3 - March To War - Team 1 Background Briefing 631

Încărcat de

9/11 Document ArchiveDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

FO B2 Public Hearing 7-9-03 1 of 2 FDR - Tab 3 - March To War - Team 1 Background Briefing 631

Încărcat de

9/11 Document ArchiveDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

THE MARCH TO WAR AGAINST THE UNITED STATES

Team One Background Briefing

The Critical Juncture

In February 1989, the last Soviet troops pulled out of Afghanistan. The Islamist

leaders of the Jihad confronted the question of "where to go next," where to direct the

"Islamic Army" (as bin Laden himself then titled it) that had evolved in the decade-long war

with the Soviets. This brought to the forefront a growing split between bin Laden, who had in

the recent years become increasingly influenced by a group of militant Egyptians, and his

erstwhile mentor Abdullah Azzam. This would prove to be a decisive fork in the path to

declaration of war against the United States by the transnational terrorist force we now know

as al Qaeda.

Both factions affirmed adherence to the long-standing Islamist goal of re-establishing the

global Caliphate under pure Quranic law (which as a universal given would require eliminating

the Israeli state).1 Their division was over how to get there.

The Egyptian militants had long ago declared the "apostate" Middle Eastern regimes

to be the principal obstacle to the ultimate objective of re-establishing a pure Islamic

Caliphate, and they saw the emergent Islamic Army as a new force for their long standing

Jihad. By the time the Soviets pulled out of Afghanistan bin Laden had come to fully espouse

this position. He was already creating his own organization, distinct from what he had until

then shared with Azzam, in which many of the top positions were held by members of the

Egyptian Islamic Jihad.

Azzam did not quarrel with the principle that bringing down the apostate regimes in the

Muslim countries was essential to the ultimate objective. But he strongly opposed what he

considered a diversion of forces, funds and other resources from what he insisted was the more

immediate task - completing the establishment of an Islamic state in Afghanistan. Although the

Soviets had withdrawn their troops they had left in place a proxy regime. He also argued that

the next priority for the Islamic Army should be expunging the Israeli "occupiers" from the

sacred Muslim lands of Palestine. Whatever resistance might have been sustained by Azzam

and his remaining supporters was taken care of on 24 November 1989 when he was

assassinated, along with two sons, in a car bombing in Peshawar.

'. The historical background is described in Daniel Benjamin and Steve Simon, The Age of Sacred Terror, (New

York: Random House, 2002) 95-109; Peter Bergen, Holy War, Inc., (New York -The Free Press/Simon and

Schuster, 2001), 40-62; Rohan Gunaratna, Inside al-Qaeda, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002) 16-

26. The split between Azzam and bin Laden and the Egyptian groups is also described in testimony by Jamal

Ahmed al-Fadl, an al Qaeda member who was there at the time and turned himself over to U.S. authorities in

mid-1996. See New York District Court: Transcripts of Trial ofUsama Bin Laden et al [African Embassy

Bombings]; Testimony of Jamal Ahmed al-Fadl, 6 Feb. 01, 189-95; 506). Fadl claims to have been formally

"sworn in" as a member of bin Laden's group in 1989 at a special meeting at a bin Laden camp (Camp Farouq)

in Khost, Afghanistan. Re "Islamic Army," see Gunaratna 22-24. Contrary to common wisdom, bin Laden did

not form his organization under the title of al-Qaeda. It was Azzam who conceptualized it in 1987, and his

article "Al-Qa'aidah al Sulbah," The Solid Foundation," in the Arabic Journal Al Jihad in April 1988 has been

described by some Arabists it as the "founding document" for the organization that has become known as "al

Qaeda." See Bergen 60ff. Fadl has said in his testimony that when bin Laden was initially forming his group,

the members referred to it both as al Qaeda and the Islamic Army, and only later adopted use of the single term

al Qaeda. (Fadel 6Feb.2001, 212)

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY 1

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

Adopting the path of Jihad against the apostate rulers of the Muslims lands would have

almost certainly led inevitably to attacks on those whom the Islamists viewed as the sources, "the

props," of the apostate leaders' power - the U.S. and other western states. The U.S. was in fact

charged with being the prop for both the "far enemy" - Israel - and "near enemies" such as the

Mubarek regime in Egypt. (And by this time bin Laden had put the Saudi regime in the same

category.) In this situation, the deployment and ultimately sustained basing of U.S. forces in Saudi

Arabia and the Gulf States in 1990 was a match in an already smoking pit, and provided a

"billboard" for bin Laden's evocations for Jihad.

Thus the evolving "bin Laden doctrine" added a new layer to the hierarchy of targets.

Before the apostate regimes could be brought down, the U.S. military forces had to be evicted

from the region. And as the focus of the Jihad became the U.S., the objectives of the Jihad

would soon expand beyond eviction from the Muslim lands to global attack against the U.S.

The Path

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan provided a common cause for Islamists whose

militancy and motivations had diverse origins. The Afghan battlefield offered a focus for

recruitment of "troops," acquisition of weapons, and the development of a command and

logistic pipeline, including transnational financial sources and movement channels. Many of

the individuals who came from the Middle East to play key leadership roles in the "Afghan

Arab" forces had been engaged in some form of their own Jihad movements long before the

conflict erupted in Afghanistan. These included bin Laden's initial mentor and partner in

Pakistan, Abdullah Azzam, as well as the Egyptian Islamists that would later comprise most

of the inner circle.

Bin Laden linked up with Azzam in Pakistan in 1984, where they jointly

established the "Bureau of Services" (Maktab al-Khidmat - MAK,). The MAK served as

a recruiting network hub - bringing fighters to Peshawar, putting them up in guesthouses, and

then dispatching them to training camps in Afghanistan. Branches would be established

around the globe, including several in the United States.

Azzam had already been a prominent figure among Islamists long before he moved to

Pakistan, issuing public calls for Jihad to return the historic Muslim lands to the governance

of pure Islamic law. He was virulently anti-Israel; he was born in Palestine in 1941, and after

receiving a degree at a Damascus university in 1966 he had returned to fight against Israel in

the 1967 war. In 1973 he took up studies in Egypt at the al-Azhar University, the most

prominent center of Islamic studies, before becoming professor of Islamic law at Abdul Aziz

University in Jeddah. His experience in Palestine and immersion in the doctrine of ancient

Muslim teachers had committed him to Jihad.2 By the end of the 1970s Azzam was dropped

by Abdul Aziz University because of his rhetoric, and he migrated to Pakistan where he

became a lecturer at the Islamic University in Islamabad.

2. Bin Laden was a student at Abdul Aziz in 1981, and thus would have known of Azzam's teachings even

before the two linked up in Pakistan. Another teacher at Al-Aziz at the time was Muhammad Qutb, brother of

Sayyid Qutb, who had been executed by Nasser in 1966, but who, as described below, continued to be the most

widely read Islamist in the Middle East and is the author of what is still considered by many militant Egyptians

to be the "manifesto" of their Islamist groups.

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY :

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

According to most accounts, when the MAK was initially formed Azzam was its

doctrinal leader while bin Laden served as his deputy and provided much of the funding. Bin

Laden essentially confined himself to shuttling between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan (with

occasional ventures into Afghanistan to establish his Mujahidin bona fides), while Azzam,

traveled the globe on recruitment and fundraising missions, which included some 20 trips to

US. The Farouq mosque in Brooklyn was one of his regular sites for lectures on the duties of

Jihad, and as is described below, one of the first branches of the MAK was set up there.

In the mid-to-latter 1980s key leaders of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) were

moving to the Pakistan and Afghanistan sites in increasing numbers, and bin Laden

became increasingly influenced by them. Many who have studied the history of the

emergence of al Qaeda have pointed out that the evidence suggests that the organization was

as much a product of the Egyptians Islamists drawing in bin Laden as is was a matter of his

incorporating them into his inner circle.

Most prominent among these was Ayman al-Zawahiri, a medical doctor, described

by some as the leader of EIJ, by others as leader of a "faction" of the EIJ.4 He had been

imprisoned for three years on weapons charges following the assassination of Egyptian

President Anwar Sadat on 6 October 1981. When released he went to Pakistan to provide

medical services to Mujahidin waging Jihad against the Soviets in Afghanistan.

Also in Pakistan at this time was Sheikh Omar Ahmad Abdel Rahman (the "Blind

Sheikh"), who was generally considered to be the spiritual guide of Egyptian Islamic Jihad

(EIJ). Many accounts claim he simultaneously served as spiritual leader for a parallel,

similar organization known as the Egyptian Islamic Group (EIG), headed by Rifai

Ahmed Taha. Sheikh Rahman had for many years issued public "Fatawas" justifying the

terrorist actions of both groups. He publicly praised the assassination of Sadat in 1981, and

was subsequently arrested and tried for his role, but ended up being acquitted. (Mubarak

apparently viewed imprisoning a/the top Muslim cleric as likely to incite more trouble that it

would solve.)

Both the EIJ and the EIG were in effect "rebellious offspring" of the Muslim

Brotherhood. The Brotherhood had emerged in the Middle East in the late 1920s in the

tumultuous post-WWI situation - the Ottoman dominion gone, much of its former territory

placed under control of League of Nation "mandates" (seen by much of the populace in the

region as an extension of European colonialism), and Palestine erupting into what would

prove to be an unending conflict. The Muslim Brothers propagated the doctrine that only

"Salafiyya" Islam - Islam purged of impurities and Western influences - could save

Muslims from the colonial powers.

By the 1950s, as the colonial powers begin pulling out, the focus of animosity turned on

indigenous leaders of the Middle Eastern states who were seen as having accepted

western law as a substitute for the Sharia - "abandoning God's law" and submitting to

"man-made law." (These "apostate" leaders were labeled as "Jahiliyya," a term originally

used to described the "barbarians" existing before the Prophet's message began to be

3. Many who have studied the history of the emergence of al Qaeda have pointed out that the evidence suggests

that the organization was as much a product of the Egyptians Islamists drawing in bin Laden as is was a matter

of his incorporating them into his inner circle. See, for example, Bergen, Holy War Inc., 199-204; Benjamin and

Simon, The New Age of Terror, 103; Gunaratna, Inside al Qaeda, 25.

4. The "faction leader" description is by Benjamin and Simon, 103.

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY 3

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

propagated.) Some Islamic scholars framed the issue in terms of the need to deal first with

the "near enemy" in their own lands before moving to combat the "far enemy" in Israel.

While the "Brothers" first emerged in Palestine/ Jordan, their doctrine had its most potent

appeal and attracted most followers in Egypt. The Al-Azhar Islamic study center in Cairo

became the main site of its transnational gatherings.

The Brotherhood doctrine nominally did not call for violence, but rather preached a

"bottom up" approach, in which conversion of the masses was seen as the way to create

power that would eventually topple the "Jahili" leaders. Nonetheless, this declared position

did not prevent the movement from engaging in significant incidents of violence in the

ensuing decades.

By the late 1960s factions within and outside the Brotherhood were explicitly rejecting

the "bottom up" concept, declaring that experience demonstrated there was no way the

apostate leaders in the historical Muslim lands would accede to a peaceful transition to a true

Caliphate. This fueled the break off the groups that formed the Egyptian Islamic Jihad and

the Egyptian Islamic Group. While the doctrine of these groups started at the same point as

the Brotherhood - immersion in the Koran - they described it as a basis for forming a

"Revolutionary Vanguard" whose mission was "Jihad" against the existing political

leaders in the lands of the Prophet. (The most influential preacher in this development was

Sayyid Qutb, who was eventually executed by Nasser in 1966, but whose books are still the

most widely read in the militant Muslim world. His "Signpost" treatise is generally

considered to be the manifesto of the militant Egyptian movements. As noted above, his

brother was teaching at Al-Azziz University in Jeddah at the time bin Laden was a student

there.)

Bin Laden and his Egyptian colleagues saw the Islamic Army that matriculated from

the war against the Soviets as having created this "vanguard;" the main question was where to

employ it next. (Bin Laden, in fact referred to his organization as the Islamic Army, of which

al Qaeda was only a central leadership "foundation.") With the defeat of the Soviets, the

Egyptians not surprisingly wanted to take the army back to pursue their fundamental

objective of ousting the apostate leaders in the lands of Islam, starting in Egypt, but

extending through the region.

Azzam's insistence on focusing the Islamic Army's resources on finishing the job

in Afghanistan and then turning to the enemy in Palestine presumably was at least in part

because of his experience in Palestine. According to some sources he also was skeptical

about the reality of prospects - at least under the existing circumstances - for ousting the

Middle Eastern rulers through militant actions. This was the same debate among the Islamists

that scholars had in earlier years described as contesting priorities between the "near enemy"

and the "far enemy."

At the time Azzam was assassinated Bin Laden was conveniently back in Saudi

Arabia. He has since routinely praised Azzam, but many suspect that he was behind the

killing. (Or perhaps it was the Egyptians who initiated and pulled it off, while bin Laden

adopted a "don't ask, don't tell" position.)

By this time bin Laden was already well down the road in forming his organization.

According to an al Qaeda defector, Jamad Ahmed al-Fadl, who claims to have formally joined

the organization in its founding stages, its inner circle was dominated by members of

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY 4

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

Egyptian Islamic Jihad. 5 Zawahiri was his principal deputy. Abu Ubaidah al-Banshiri,

former Egyptian police officer and prominent participant in the Jihad battlefield in

Afghanistan, was the first "military chief," while Muhammed Atef, (aka Abu Hafs al

Masry) another EIJ member, was deputy chief of operations, and ultimately would succeed

Banshiri after his death a few years later. According to several sources with direct access, at

the same time Zawahiri held this principal deputy position in al Qaeda's Shura, he

continued to hold a leadership position in the EIJ, and the two organizations pursued a

common agenda in Egypt. (Members of al Qaeda who have since defected or been

apprehended have said many key players belonged simultaneously to both al Qaeda and a

terrorist entity in their countries of origin.)

Other members of the initial inner circle or "Shura," whom the source knew only by

their pseudonyms, included:

" An additional Egyptian - Sheikh Sayyid el Masry.

• Three Saudis (in addition to bin Laden - Abu Musab al Saudi, Abu Saad al

Sharif Abu Mohamed Saudi, and Abu Fadl al Makkee)..

• Three Iraqis - Mamudh Salim, aka Abu Hajer who managed weapons

procurement; Abu Ayoub and Abu Burhan.

• A Yemeni (Abu Farij); a Libyan (Saif al Liby); an Omani (Khalifa al

Muscat), and a Nigerian (Qaricrpt al Jizaeri).

Beneath the Shura were a series of committees, usually chaired by one or more

members of the Shura. These included

• The military committee, initially chaired by Banshiri with Atef as his deputy

(and ultimate successor).

• A finance or "business" committee, initially chaired by Abu Fadhl al

Makkee.

• A Fatawa Committee, chaired by Abu Saad al Sharif Abu Mohamed Saudi.

This composition, and the linkages and affiliations that the organization has continued

to demonstrate since then, suggest that its most descriptive title would the one - "The

International Islamic Front" - under which it issued its "Fatawa" enjoining Muslims of the

world to wage holy war against the western "crusaders."

An early bin Laden effort at toppling an "apostate" regime occurred in October 89.

when he offered bribes to Pakistan parliamentarians to support a no confidence resolution

against Pakistan Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto. She narrowly survived the vote on 1 Nov. In

a later interview, Bhutto said some parliamentarians who had been offered money told her it

came from Saudi sources. She said that when she queried the Saudi government she was told

that bin Laden had put up the money, and that this was the first she had heard of him. She

also said, however, that whatever bin Laden's role in providing the money, she was convinced

that the initiator of the scheme was the chief of Pakistani intelligence (ISI)., who had been

running the CIA support channels to the Afghan Mujahidin and who had both the motivation

and the necessary connections to set up the scheme.

5. The description of the initial leadership and structure is given in the Fadl testimony, 6 Feb. 2001, 193-211;

221; and 13 Feb., 510-514. This includes Fadl's account of his official "swearing in" process.

6. Bergen, Holy War, Inc., 61-62, describing his interview with Bhutto.

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

COMMISSION SENSITIVE

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Science of ColorDocument71 paginiThe Science of Colorephraim7100% (5)

- 2012-156 Doc 20Document1 pagină2012-156 Doc 209/11 Document Archive0% (1)

- Open Letter To Pres Obama About DemocracyDocument55 paginiOpen Letter To Pres Obama About Democracymelsomfer2003Încă nu există evaluări

- Commission Meeting With The President and Vice President of The United States 29 April 2004, 9:25-12:40Document31 paginiCommission Meeting With The President and Vice President of The United States 29 April 2004, 9:25-12:409/11 Document Archive100% (1)

- 2012-156 Larson NARA-CLA Release Signed Copy2Document7 pagini2012-156 Larson NARA-CLA Release Signed Copy29/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 25Document3 pagini2012-156 Doc 259/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 24Document1 pagină2012-156 Doc 249/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 26Document20 pagini2012-156 Doc 269/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 22Document2 pagini2012-156 Doc 229/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 14 Part 2Document22 pagini2012-156 Doc 14 Part 29/11 Document Archive100% (1)

- 2012-156 Doc 21Document23 pagini2012-156 Doc 219/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 14 Part 1Document18 pagini2012-156 Doc 14 Part 19/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 12 Part 1Document26 pagini2012-156 Doc 12 Part 19/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 9 Part 1Document25 pagini2012-156 Doc 9 Part 19/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 13 Part 1Document25 pagini2012-156 Doc 13 Part 19/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012-156 Doc 5 Part 1Document22 pagini2012-156 Doc 5 Part 19/11 Document ArchiveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women and CultureDocument68 paginiWomen and CultureOxfamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Qurani DuaayenDocument48 paginiQurani Duaayentawhide_islamicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Category D p2Document102 paginiCategory D p2Md Sefat UllahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Position Paper in Oral CommunicationDocument3 paginiPosition Paper in Oral CommunicationJennine Julia VallejosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Easy Good DeedsDocument2 paginiEasy Good DeedsMohamed YousufÎncă nu există evaluări

- Simple Tenses QuizDocument1 paginăSimple Tenses QuizNina Ricci CaasiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sin of Riba (Usury)Document2 paginiThe Sin of Riba (Usury)jamsheedkhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tafseer As Sadi Volume 04 Juz 10 12 EnglishDocument418 paginiTafseer As Sadi Volume 04 Juz 10 12 EnglishThe ChoiceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smbbmu PM Laptop Final List 180823Document57 paginiSmbbmu PM Laptop Final List 180823Muhammad AyoubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allaah Has No Need That He Should Leave His Food and Drink." Meaning: That Allaah, The Mighty and MajesticDocument6 paginiAllaah Has No Need That He Should Leave His Food and Drink." Meaning: That Allaah, The Mighty and MajesticAnisur ShawonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teks MCDocument6 paginiTeks MCNopiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sheikh Zayed Medical College SZMC Open Merit List 2013Document11 paginiSheikh Zayed Medical College SZMC Open Merit List 2013Shawn Parker0% (1)

- Phase-1 Development and Contribution of Ideology Before 1947.Document11 paginiPhase-1 Development and Contribution of Ideology Before 1947.MIAN WasiFÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Globalization of Religion Written ReportDocument4 paginiThe Globalization of Religion Written ReportVanessa Castor GasparÎncă nu există evaluări

- Govt Primary School Chak NoDocument6 paginiGovt Primary School Chak NoRashid MahmoodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compiled Du'aasDocument25 paginiCompiled Du'aasHabib AnsariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islam and The Economic Challenge PDFDocument448 paginiIslam and The Economic Challenge PDFAnezi SatÎncă nu există evaluări

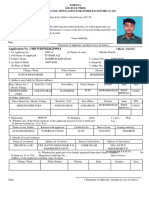

- ApplicationdetailsDocument1 paginăApplicationdetailsSirajdulla skÎncă nu există evaluări

- BU Ali SinaDocument6 paginiBU Ali SinaMaryam ShahzadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre-Islamic Arabic Prose Literature & Its GrowthDocument239 paginiPre-Islamic Arabic Prose Literature & Its GrowthShah DrshannÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mishkat Al-Anwar 101 Diamonds Hadith Al-Qudsi Collected by Al-Shaykh Al-Akbar Ibn Al-'ArabiDocument57 paginiMishkat Al-Anwar 101 Diamonds Hadith Al-Qudsi Collected by Al-Shaykh Al-Akbar Ibn Al-'ArabiDanish Kirkire Qadri Razvi100% (3)

- Hana Fiqh Hana FiqhDocument17 paginiHana Fiqh Hana Fiqhnazeerahmad50% (2)

- Week 11 - Islamic Political Thought - Ibn RushdDocument44 paginiWeek 11 - Islamic Political Thought - Ibn RushdMedine Nur DoğanayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morality and Ethics in IslamDocument24 paginiMorality and Ethics in IslamTeguh HardiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Islamiat Introduction To CourseDocument23 pagini1 Islamiat Introduction To CourseAijaz Ahmed LakhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indenture of Madrasah Suffatus SahaabahDocument9 paginiIndenture of Madrasah Suffatus SahaabahmusarhadÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Chosen OneDocument11 paginiThe Chosen OneAmir KazmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dars-E-Nizami Is A Syllabus of Books Taught in All ... - Amazon S3Document2 paginiThe Dars-E-Nizami Is A Syllabus of Books Taught in All ... - Amazon S3Mounesh7100% (3)