Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Population Roman Alexandria

Încărcat de

Walther PragerDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Population Roman Alexandria

Încărcat de

Walther PragerDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

American Philological Association

The Population of Roman Alexandria Author(s): Diana Delia Source: Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), Vol. 118 (1988), pp. 275292 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/284172 . Accessed: 26/07/2013 08:14

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Philological Association and The Johns Hopkins University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-).

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

American Transactions ofthe Philological Association 118 (1988) 275-292

THE POPULATION OF ROMAN ALEXANDRIA

DIANA DELIA TexasA&M University Abu Zayd ibn Khald'un, once The eminent Arab historian, 'Abd ar-Rahman thesize of a city's a highly existsbetween that observed positivecorrelation whichit enjoys.' and prosperity populationand the degree of civilization on Alexandria ad Accordingly, one would expect the ancienttestimonia Aegyptum, a cityoften eulogizedas a crossroads of thecivilizedworld,in in greatness secondonlytoRome,torevealthat itspopulation was considerable size. Regrettably, thesourcesare bothfewand controversial. Nevertheless, on the basis of these some scholarshave postulated estimates for population perseverance Alexandria.2 To be sure, suchendeavors area credit tothededicated of ancient historians; yetpopulation estimates are onlyas validas thesources on whichthey This are basedand themethodology bywhichthey arederived. toreassess study proposes theancient evidence for Alexandria as wellas modem

1 Al-Muqaddimah (Kitab al 'Ibar) II 236; cf. H 244. 2 On the praise of Alexandria,see: Diodorus Siculus 17.52.5; Josephus, AJ 4.656; Plutarch,Mor. 207a-b; Aelius Aristides,Or. 26; Dio Chrysostom, Or. 32.35-40 and 47; HA: Firmus 8.5; Ammianus Marcellinus 22.16.7; Achilles Tatius 5.1; cf. Diodorus Siculus 1.50.7, IG 12.1561, and ZPE 41 (1981) 71-83. Modern attemptsto assess the population of Alexandria: J. Beloch, Die Bevoblkerung der griechisch-romischen Welt (Leipzig 1886) 259, followedby W. L. Westermann, "Concerning Urbanismand Anti-urbanism in Antiquity," Farouk University. Bulletin of the Faculty of Arts 5 (1949) 87: 500,000; T. WalekCzernecki,"La populationde l'tgypte ancienne,"Congres international de la population,II: Demographiehistorique(Paris 1937) = Actualite's scientifiques et industrielles, no. 711 (Paris 1938) 12-13: 1,200,000 to 1,500,000; A. von Premerstein, Alexandrinischen geronten vor Kaiser Gaius: Ein neues Bruchstiick der soggennantenAlexandrinischen Martyrerakten, Mitt. Papyrussaml.Giess. Univ. 5 (Giessen 1939) 55: 600,000; J. C. Russell, "Late Ancientand Medieval Populations," TAPS 48 (1958) 66-67: populationdensityof 235 per hectare; Mostafa el-Abbadi,The Alexandrians fromthe Foundation of the Cityto theArab Conquest (Diss. Cambridge University1960) 115-22: 500,000; P. A. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria (Oxford1972) 11 172: 1,000,000;P. Salmon,Population et depopulationdans l'empire romain,Coll. Latomus 137 (Bruxelles 1974) 35; R. Duncan-Jones, The Economy of the Roman Empire: Quantitative Studies2 (Cambridge1982) 276: populationdensity of 326 to 420 per hectare;L. Koenen, on a special panel on ancient Alexandria at the 1985 annual meetingof the AmericanPhilological Association in Washington, D.C., in response to an earlier version of this paper, 3: 500,000 to 1,000,000. See also A. Segre, "Note sull' economia dell'egittoellenisticonell'eta tolemaica,"BSAA 29 (1934) 25666.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

276

Diana Delia

of ancientcities and to suggesta of estimating methodologies populations maximum of Alexandria reasonable, rangeforthetotalpopulation the during early Principate. The risingwatertable, shorelinesubsidence, and generalhumidity at Alexandria have doomedall papyri in situ. Henceno censusrecords buried of tax-payers andproperty norevencomprehensive owners citizen akinto registers at Oxyrhynchus thosepreserved have survived.It happens or in theFayyum thatan archivecontaining morethana hundred documents of Augustan date whichrelateto the private and businessinterests of Alexandrians has been preservedin the formof mummy at Abusir-el-Melek, in the cartonnage Herakleopolite nome (BGU IV 1050-1061and 1098-1129). However,the evaluation ofthese documents as representative oftheAlexandrian as population a whole occasions difficulties, as it is notclear thatthearchiverepinsofar a random resents sampling of documents rather than a selection of documents pertaining only to certain groupsof Alexandrians-for example,thosewho their addressed to theAlexandrian petitions bureausupervised by an E?ad roV icpt-rrlptoa, whoseprecise jurisdiction and dutiesare unknown.3 For thesame reasons, statistics based on thedocuments in thisarchive wouldnotaccurately in Alexandria reflect ethnic ratios andshould notbe utilized as a basison which toproject population estimates. Relatively fewinscriptions of Romandate have survived at Alexandria. Some remain buried under the moderncity; undoubtedly others were incorporated intoByzantine buildings or consigned to thelimekilnbecauseof their remote significance or reminiscence of thepaganpast. A glanceat the majorcorpusof Alexandrian inscriptions editedby EvaristoBrecciain 1911 a typical indicates array: votive, sepulchral, honorific, andpublic.To date,this corpushas been supplemented by fewer thanone hundred stones, butnoneof theseinscriptions shedsany light whatsoever on thesize of thepopulation in theRomanperiod;forso significant a city, theepigraphic remains are indeed meagre. Had more inscriptions survived, they wouldno doubt reflect onlythat small portion of thepopulation whose municipal serviceinspired or whose affluence madepossible theerection ofinscribed monuments.5 As in thecase ofother citieswhich havebeencontinuously inhabited since antiquity, most ofancient Alexandria remains unexcavated and unexplored. The first and onlycomprehensive attempt to maptheareaof theancient cityandto charttheplan of its streets was conducted in 1866 by theroyalastronomer,

3 D. Delia, Roman Alexandria:Studies in its Social History(Diss. Columbia University 1983) 27, note 3; cf. W. Schubart, "Alexandrinische Urkunden aus der Zeit des Augustus," ArchP 5 (1913) 57-60, and el-Abbadi, Alexandrians (above, note 2) 117-18. Von Premerstein, 55, and Fraser,PA I 91-92, had excessive confidence in the figures deriving fromthisarchive. 4 Catalogue gene'raldes antiquites egyptiennes du Musee d'Alexandrie, nos. 1568: Iscrizionigreche e latine (Cairo 1911); subsequently unearthed inscriptions have been sporadically publishedin BSAA. 5 On the inherent class bias in inscriptions, see K. Hopkins,"On the Probable Age Structure of the Roman Population," PopulationStudies 20 (1966) 247.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Population ofRomanAlexandria

277

to Mahmoud Bey el-Falaki. His resultswere distorted by indifference to distinguish failure stratigraphy, amongPtolemaic, Roman,and Byzantine ofrelative Greek assessment metrical masonry, andarbitrary equivalents among to reconcile anr&6toand Romanmilia in an attempt discrepancies amongthe el-Falaki'splan has been literary sources. For lack of systematic excavation, of thecity the traditional starting pointof nearly everytopographical study In viewofitsserious hisplan published sincehisday.6 shortcomings, however, of shouldbe abandoned.One can only hope thattheEgyptian Department Antiquities will undertake seriesof trial excavations on land and a a uniform harbor and shoreline so that of thesubmerged Eastern thorough investigation these as a scientific basison which toreconstruct mayserve plansoftheancient city.7 Insofar as thephysical dimensions ofAlexandria areconcerned, thedisparity amongliterary sourcescan probably be reconciled on thebasis of inclusion or exclusionof various7tpo&cY-rutx, or suburbs, by ancient authors, and by our awareness that thecircuit of thecitywas notconstant, butvariable, expanding and shrinking overthecourseof time.Burialpattems indicate that in theearly Ptolemaic period, theeastern citylimit extended roughly as far as Cape Lochias (modernSilsileh) and, in keeping with Greek burial custom,cemeteries commenced justbeyond thiswall,at Chatby and Hadra.By theendof thefirst century B.C., however, theseold nekropoleis had been abandoned in favor of cemeteries located further eastat Ibrahimiya andSporting anda neweastem wall was erected; thearea in between appearsgradually to havebeeninhabited and wouldremain residential during the Roman period.8

6 Memoire sur l'antique Alexandrie (Copenhagen 1872); el-Falaki's plan is conveniently reproducedin A. Adriani, Repertorio d'arte dell'Egitto grecoromano, ser. C (Palermo 1963-66), II, tav. 3. As early as 1894, D. G. Hogarth rejected el-Falaki's plan: "Reporton the Prospectsof Research in Alexandria," Egypt Exploration Fund Archaeological Report (1894-5) 17-18, note 1. Notwithstanding Hogarth's criticism, G. Botti's Plan de la ville d'Alexandriea' l'e'poque ptolemaique (Alexandria 1898) was substantially based on el-Falaki's work.E. Breccia,Alexandriaad Aegyptum (Bergamo1922) 71-76, and Fraser, PA I 13-14, echoed Hogarth'scriticisms. However,A. Adrianiand his students have been inclinedto return to el-Falaki's plan: "Saggio di una pianta archeologicadi Alessandria," Annuario del Museo greco-romano 1932-33, 53-57 and passim, and Repertorio I 18 and 55-57. Most recentlysee G. Caruso, "Alcuni aspetti dell'urbanistica di Alessandriain et'a ellenistica:il piano di progettazione," in N. Bonacasa and A. di Vita,edd.,Alessandriae il mondoellenistico-romano. Studi in onore di AchilleAdrianiI (Roma 1984) 43-53. 7 H. Frost,"Reportand Recommendations on the Submerged Architecture and Statuesat the Site of the AncientPharos,FortKhait Bay, Alexandria," submitted to the Marine Information Center,UNESCO (1968?); see also the same author's "The Pharos site,Alexandria, Egypt," J. Naut. Arch.4 (1975) 126-30. 8 On the Ptolemaicnekropoleis, see Adriani, RepertorioI 21; Fraser, PA 1 1213; and my figure1, p. 292 below. On inhabitation of the Chatby-Hadra area during the late Hellenistic and early Roman periods, see Neroutsos-Bey, L'ancienneAlexandrie:Etude archeologiqueet topographique (Paris 1888) 80-83;

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

278

DianaDelia

residedin Egyptfrom circa 25 to 19 B.C. His east-west Straboactually estimate(17.1.8 and 10) of 30 a 5tax fromthe Canopic gate bordering Ibrahimiya on theeast to slightly canal on thewest beyondtheMahmudiya measurement ofroughly compares 5.5 km.9 favorably with themodem Strabo's north-south measurement of 7 or 8 at6uta at the isthmoi, or narrowest distances between theMediterranean is approximately Sea and Lake Maryut, equivalentto the modem1.5 km. distancealong the western branchof the Mahmudiya canalwhich empties outintothewestern harbor. Todaythedistance from theMediterranean coastat Ibrahimiya to Lake Maryut measures about4 km.Some of thisarea appearsto havebeennatural landfill of theold lakebed which originally mayhaveextended as farnorth as thepresent lateral courseof the Mahmudiya canal; accordingly, theancient canal was probably situated farther north as well.10Except forhis measurement of theeasternisthmus, Strabo's estimateof the dimensionsof the Roman city are nevertheless corroborated bothby thetopography of themodem cityand by archaeological evidenceof thecitylimitsin thelate first century B.C in light of traditional burialpractices. Relying on hisfigures, we mayestimate that thecitywallsof Alexandria during thereignof Augustus enclosedan area measuring 8.25 sq. km.or 825 hectares.1" Four criteria traditionally employed to estimate urban population density are thearea of thecitywithin its walled circuit, thesize of its suburbs, the extent to whichtheseareas wereoccupiedby residential dwellings, and, in connection therewith, theratioof town-houses to apartment buildings1I2 We

E. Breccia, "La necropoli di Sciatbi," BSAA 8 (1905) 55-56, and Catalogue ge'ne'raldes antiquite'sd'Egypte, nos. 1-624: La necropoli di Sciatbi (Cairo 1912); A. H. Tubby et al., "An account of excavationsat Chatby,Ibrahamieh, and Hadra," BSAA 16 (1918) 79-90; A. Adriani, "Scoperte de tombe," Annuariol 932-1933, 35-36, and "Vestiges de 1'6poque romaine a Chatby," Annuairedu Musee 1935-1939, 149-50. 9 One (yta6tov is equivalentto 606.75 modem feet,and thereare 5.4 Gt6a6ai per km. Modern measurements are based on the EgyptianMinistry of Finance, Surveyof Egypt, Pocket Atlas of Alexandria(Giza 1935), plates 5-7 and 11-13. 10 In general, see A. De Cosson,Mareotis (London 1935). 11 Cf. Beloch, Bevolkerung 258-59, followedby Duncan Jones,Economy276, who proposedan area of 920 hectares. The east-west dimensions preserved by Diodorus Siculus (17.52) of 40 sat66a and by Steph. Byz., s.v. 'AXc.t6v6pltat IEXELt; (Meineke), of 34 st6a6a probablyincluded suburbs.Josephus(BJ 2.385) corroboratedStrabo's lateral measurement of 30 ast6ta. Cf. Pliny,NH 5.92: 15 milia wide. Northsouth dimensions of 10 iar6aia preserved by Philo (in Flacc. 92) and Josephus (BJ 2.385) probablyincluded the causeway and island of Pharos, to which the northern wall extended: Bell. Alex. 17; cf. Steph. Byz. loc. cit., for 8 Gta'uta fromnorthto south.On the extent of the circuitat the timeof the city's foundation,see Q. CurtiusRufus4.8.2 and Steph.Byz. loc. cit. 12 L. Homo, "Topographieet demographie dans la Rome imp6riale,"CRAI (1933) 298 and 304; R. Meiggs, Roman Ostia2 (Oxford 1973) 532-34--cf. the studiesby Packercited in note 17 below; C. Clark,Population Growthand Land Use (New York 1967) 178-9; A. Lezine, "Sur la population des villes africaines,"

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ThePopulation ofRomanAlexandria

279

havealready to havebeen 825 hectares estimated thearea of thecity proper in the Augustanperiod. The names and approximatelocations of several ipoaca'rta are knownbutit is uncertain how farextramurosthesesuburbs when one attempts extended (a similar is encountered todetermine problem the relationship of the ager Romanusto Rome); nor is it knownwhether their inhabitants wereincluded in thepopulation forAlexandria estimates preserved byclassicalauthors.13 Since,forthemost theratio part, Alexandria hasremained of unexcavated, in boththeurban publicbuildings, palaces,andparks to shopsand housing and suburban areas also remains whollyunknown. over thecourseof Moreover, time,theproportions would have varied.Straboclaimedthatin his day,the BovX-ci, orroyalquarter, comprised one-quarter to one-third of thetotal area of thecity(17.18.). Threegenerations later, theelderPlinyallotted onlyonefifth of thetotalarea to theroyalquarter (NH 3.9.62). Moreover, although literary sourcesattest to theexistence of many publicbuildings at Alexandria, includingbaths, theatres, bouleuteria,gymnasia,hippodromes, and amphitheaters, their precise locations andrelative proportions areunknown. Indeed, theonlypublicstructures that havebeenunearthed at Alexandria are theodeon and bathsat Kom el-Dikka;theformer, originally builtin thefourth century A.D., was twicereconstructed thereafter with seating capacity for approximately one thousand spectators, and thebathsare Byzantine in date.14However, the capacity of public buildingsin a city which attracted visitorsfromthe countryside is nota reliable reflection of thesize of theurban population.15

Ant.Afr.3 (1969) passim; and J.C. Russell, "The Populationand Mortalityat Pompeii," Bulletin of the International Commissionon UrgentAnthropological and EthnologicalResearch 19 (1977) 109. 13 On the difficulties encountered in distinguishing the city proper fromits own territory, or Chora, see A. di Vita, "L'urbanistica piiuanticadella colonie di Magna Grecia e di Sicilia: Problemie riflessioni," ASAtene59 (1981) 66-71. On the AlexandrianChora see A. Jahne, Alexandreiain Agypten:die Erhebungzur ptolemaischeMetropole,die chora der Stadt. Diss. HumboldtUniversity, Berlin (1980); and "Die 'AX ?4av5p?ov Xcopa," Klio 63 (1981) 63-103. 14 A. Calderini, Dizionario dei nomigeograficie topografici dell'Egittogrecoromano 1.1 (Cairo 1935), "Alexandreia," passim; see also Adriani, RepertorioII 201ff. (Glossario di topografia). For totals of baths, taverns,porticoes and temples,see below, note 17. On theodeon at Kom el-Dikka,see Fawzi el-Fakharani, "The odeon of Kom el Dick," Cahiers d'Alexandrie 4 (1966) 32-36; cf. his "Les decouvertes archeologiquesd'Alexandrie,"ibid. 18-27, and E. Makowiecka,"The Numbering of theSeatingPlaces at the RomanTheatreof Kom el Dikka,"Acta ConventusXI Eirene (1968) 479-83. Recently, J.-C. Balty suggested that this building functioned as a bouleutarion: "Le bouleuterion de l'Alexandrieseverienne," Etudes et Travaux 13 (1983) 8-12. The fundamental and most recentstudyof the baths is by M. Rodziewicz, "Thermesromainspres de la gare centraled'Alexandrie,"Etudes et Travaux 11 (1979) 108-38. l5 Russell (1977) 108.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

280

Diana Delia

Curiously,the only housing remainsof Roman date discovered at theearly Ptolemaic Alexandria belongto villas;twoof thesewerebuiltwithin that Arewe therefore to infer and one was constructed at Chatby.16 citylimits thanOstia and Rome? Alexandria developedon themodelof Pompeiirather forin a cityof Alexandria's wouldbe an absurdity, Surelysucha conclusion it would certainly be reasonable to assume the commercialimportance, insulae whose existenceof numerous multiple dwellings-thosenotorious precise definition has generated endless dispute.17 Moreover, evenifremains of pre-Byzantine multiple dwellings werediscovered at Alexandria, howaccurate in whichstairs wouldmodemestimates be, based as they are on thedirection presumably ran on storeysno longerextantand the relativethickness of foundation walls?Also conjectural is therestoration of upper storeys based on ground storey or mezzanine plans. At best,theseareeducated guesses.18 Thus we would be unableto arriveat a realistic approximation of thenumber of households in a building even if we could estimate thenumber of apartment

16 On the "House of the Birds," a Roman villa built in the middleof the first century and destroyed by the end of the third A.D. at Kom el-Dikka,see century M. Rodziewicz,"Un quartier d'habitation a Kom el-Dikka,"Etudeset greco-romain Travaux 9 (1976) 175-92. For the remains of a Roman villa at Chatby, see above, note 8. Concerning the remainsof a privateRoman bath whichbelonged to a villa dating to the firstor second century A.D. at Kom el-Dikka, see K. Kolodziejczyk,"PrivateRoman Bath at Kom el-Dikka in Alexandria,"Etudes et Travaux 2 (1968) 144-54; cf. J. Lipinska,"Polish Excavationsat Kom el-Dikka in Alexandria,"Etudes et Travaux 1 (1966) 184-85. On Byzantinehouses excavated in the center of the city, see M. Rodziewicz, Alexandrie III: Les habitations romainestardivesd'Alexandrieai la lumieredes fouillespolonaises a Kom el-Dikka(Warsaw 1984). 17 For the existenceof insulae and domus in Roman Alexandria,see Michael Bar Elias, Chronic. 5.3, ed. and tr. J.-B. Chabot (Orfa 1899-1910), I 113-115, and P. A. Fraser,"A Syriacnotitiaurbis Alexandrinae," JEA 37 (1951) 107, note 7. Fraser astutely observedthatthe absence of Christian buildingsand inclusion of the Serapeum,destroyedin A.D. 391, suggest thatMichael's source for the notitia predatedthe "triumph of Christianity" in the fourth century A.D. Similar fourth-century lists survivefor the city of Rome: see Codice topograficodella cittadi Roma, edd. Valentiniand Zuchetti (Rome 1940), and G. Hermansen, "The Populationof Imperial Rome: The Regionaries," Historia 27 (1978) 129-68; cf. fragments of the Severan plan: G. Carettoni et al., La pianta marmoriadi Roma antica I (Rome 1960). At Ostia, two-thirdsof which has been excavated, the ratio of multiple dwellings to private villas was an overwhelming184:22. See J. E. Packer, "Housing and Populationin ImperialOstia and Rome,"JRS 57 (1967) 83-86, and "Urban Life and Society in ImperialOstia and Rome," MAAR 31 (1971) 66 and 80. Packerdrewinferences from theOstianevidenceforRome,as had von Gerkan earlier:"Die Einwohnerzahl Roms in der Kaiserzeit," MDAI:R 55 (1940) 149-95, and "Weitereszur Einwohnerzahl Roms in der Kaiserzeit,"MDAI:R 58 (1943) 213-43. 18 Packer, JRS (1969) 84-87, and MAAR (1971) 66-68. See also B. W. Frier, Landlordsand Tenantsin ImperialRome (Princeton 1980) 3-20.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Population ofRomanAlexandria

281

makes it buildingsin Roman Alexandria.In sum, the evidenceat present impossible to estimate of thiscity. thepopulation density Moreover, lackofdocumentation thepossibility from Alexandria precludes of estimating of foundations theaverageurban household size andno evidence can be made.19 To be survives on which an estimate of thenumber of families sure,thelandmark from studies of censusdeclarations theOxyrhynchite and Arsinoite nomes by Calderini, Hombert and Preaux illuminate our understanding of themeanfamily size in Egyptian statistics villages.However, derived rural from on which tobase a profile ofthe villages arenotvalidmodels populationof an urbanmetropolis Valuable data and provincialcapital.20 contributing toourunderstanding oftheaverage family size suchas male:female ratios andmortality couldhavebeengleaned from thestudy ofskeletal remains, especiallythosefrom the three-storied catacombutilizedfrom thelate first theearlyfourth through in Alexandria, centuries A.D at Kom el-Schoqafa but these skeletons werenotexamined andno datawas preserved.2l Moreover, what is a reasonable estimatefor the proportion of slaves to free persons in antiquity's big cities?22 Finally, theattempts to attribute to RomanAlexandria population estimates based on analogies withmodempopulations are both arbitrary and unconvincing; how does one go aboutchoosing areas and dates which presentreasonableparallels?23 In short, to base an estimate of the

19 For example,see R. P. Duncan-Jones, "HumanNumbersin Towns and Town Organizations of the Roman empire:The Evidence of Gifts,"Historia 13 (1961) 205-8. 20 A. Calderini, La composizione della famiglia secondo le schede di censimentodell'Egitto romano (Milano 1923) 54; M. Hombertand C. Preaux, Recherches sur le recensement dans l'Egypteromaine, Pap. Lugd. Batav. 5 (Leiden 1952) 154-55 and 163. 21 See W. W. Howells, "Estimating Population Numbersthrough Archaeological and Skeletal Remains," and H. V. Vallois, "Vital Statistics in Prehistoric Populationas Determined fromArchaeologicalData," in R. F. Heizer and S. F. Cook, edd., The Applicationof Quantitative Methodsin Archaeology (New York 1960) 158-85 and 186-222, respectively. 22 W. L. Westermann'sestimateof 25 to 30 percent for the proportion of slaves to the total population of a large ancient metropolis may be high: "Slavery," Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences 14 (1934) 76; see also his "Urbanism and Anti-urbanism" (above, note 2) 87 note 6. Beloch's estimatefor the slave population of Roman Alexandria was based on that of Pergamum: Bevblkerung, 259. Conversely,F. G. Meier concluded that it is impossible to determine the numberof slaves even in an ancientcity as well documented as Rome: "Romische Bevolkerungsgeschichte und Inschriftenstatistik," Historia 2 (1953-54) 336-44. 23 Boak's sources for the male:female ratio in Roman Egypt were early twentieth century census reportsfromChina, India, and Egypt:"The Population of Roman and Byzantine Karanis,"Historia4 (1955) 159; see also Duncan-Jones, Economy(above, note 1) 276-77, and A. R. Burn,"Hic brevevivitur: A Studyof the Expectationof Life in the Roman Empire,"P&P 4 (1953). For objections against relying on population density figures from the Moslem period, see

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

282

Diana Delia

of RomanAlexandria population on anyof theforegoing wouldbe to place in a housebuilt one's trust ofcards. Whenone turns to theliterary one is confronted sources, by thesobering pronouncement of A. H. M. Jones: I shallbe able toconceal "itis unlikely that the ignominious truth, thatthere are no ancientstatistics."24 Jonesastutely observed that ancient to figures literary sourceswereindifferent of economic significance; as a result, in terms dataare scant and so diverse of datethat they are scarcelycomparable. [ioreover,notedJones, manuscript copyistswere mostlikelyto errin thetaskof copying An excellent figures. exampleof this is thenotitia urbisAlexandrinae in theSyriacchronicle preserved of Michael Bar Elias whichcontains twosetsof figures: thefirst groupare entries of the number of particular typesof buildings in each of thefiveregionsof urban Alexandria andthesecondgroup consists oftotals for theentire city bybuilding types which, however, do notequatewith thesumsof theindividual entries apin thefirst pearing set.25 One consideration essential to theevaluation of ancient literary sourcesis the reliability of the evidence on which theirfiguresrest. For example, Josephusrelatesthatthe totalpopulation of Egyptwas seven and one-half million excludingthe populationof Alexandria,60) EvcEvtv Eic 'rf0;ICxO' EIc6cvrriv ]cEpcaXiv Eio(pop&; tEictpcaoOct (BJ 2.16.4). Even werewe to assumefrom thisstatement that Josephus hadaccess to thecomplicated records of the Xcoypwpit, or poll tax, to whichonly adult males were subject,

Lezine, 78-79. I would not be so rash as to rule out modern demographic parallels if an adequate samplingof vital statistics fromRoman Alexandriahad survived.In that case, reasonable approximations of life expectancymightbe gleaned fromtables in A. J. Coale and P. Demeny,Regional Model Life Tables and Stable Populations(Princeton 1966). See, forexample,B. Frier, "Roman Life Expectancy:the PannonianEvidence," Phoenix 37 (1983) 328-44, and "Roman Life Expectancy: Ulpian's Evidence" HSCP 86 (1982) 213-51. See also K. Hopkins, Death and Renewal (Cambridge 1983) 69-107; R. ttienne, "Demographic et epigraphie,"Proceedingsof the III International Congress of Greekand Latin Epigraphy (Rome 1957) 415-24, and I. Kajanto,On the Problem of theAverageDurationofLife in theRomanEmpire.Annales Acad. Scientiarum Fennicae, ser. B, 153.2 (Helsinki 1968). An essential precondition for demographic investigation cited by G. Acsadi and J. Nemeskeriis completenessof evidence or, in the event thatthis is lacking,a randomsampling:"Methods of Paleodemographic studies," in Historyof Human Life Span and Mortality (Budapest 1970) 57-58. See also N. Keyfitzand W. Flieger,Population: Facts and Methods of Demography (San Francisco 1971) 567-92, and P. Cox, Demography5 (Cambridge1976) 20-45. 24 AncientEconomic History. Inaugurallecturedeliveredat University College, London (1948) 3. See also M. I. Finley,"Le document et l'histoire 6conomiquede l'antiquit6," Annales. E.S.C. 37 (1982) 697-713 = AncientHistory:Evidence and Models (New York 1987) 27-46. 25 See above, note 17. In connection withsimilarfourth-century tallies for the city of Rome, Hermansen(1978) 159 suggested that the awe and admiration inspiredby thatcityinflated the figures. The same suggestion may be entertained in connection withthe notitiaurbisAlexandrinae.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Population ofRomanAlexandria

283

numerous indicatethatmanymales throughout documents Egyptenjoyed from them to pay or partially priviliged status whichwholly exempted liability thistax. Hencethereliability ofJosephus' estimate necessitates his having had access to figures as well as thesummaries of family forall of thesecategories sizes and household declared on individual censusreturns staffs fourteen every The likelihood all of thesesources years.26 wereconsulted that byJosephus is remote. Another case at handis DiodorusSiculus' (1.31.8) estimate of seven million in Pharaonic in his forthepopulation of Egypt times and three million ownday,circa60 B.C. Dindorf in hisedition thesecondfigure ofthe expunged text;subsequent editors cast doubtby bracketing thepassagereads: it,so that

,roi E

R)putc

making thepassage compatible withtheestimate of Josephus. Unfortunately, Diodorusdoes notdisclosethesourceof his information, although hisaccount mayhaveserved as oneofJosephus' sources.27 Heeding Jones' caution thatclassical authorswere indifferent to the statistical ramifications of their figures, we shouldnotreadintotheir choiceof termsa deliberateattempt at technicalaccuracy.Hence Walek-Czernecki probably goes too farin contrasting inclusiveof Xeka-the totalpopulation females andchildren, with to adultmalecitizens. &Fjgo;-whichhe wouldlimit To be sure,theformer is a general term, unlimited by gender and age, butthe included women, despite their lackofpublicvisibility and exercise of franchise in Helleniccities.28 Our onlykeyfigure forthepopulation of RomanAlexandria is preserved by DiodorusSiculus,who claimedthatin his own day,circa 60 B.C., more than three hundred thousandkXE0Epot resided there (17.52.6).Diodorus citesas

his source o't x'r; &vwypup&;

EXovTE;

Xaob To REV nLUakataov (past cIt71CVTo; g&E; iC OK iX&ttoU; 0;, Kiot Kax'

YE OvEvaLt

lEpt

En'T?oota

tvat [Tptocxoctcov], thus

lattermay be no more exclusive than the termoi noXitTat, which certainly

'Trv

xToticoivTOv, but both the

26 S. L. Wallace, Taxation in Egyptfrom Augustusto Diocletian (Princeton 1938) 116-34. See also A. C. Johnson, Roman Egypt (Baltimore 1936) 531-36, who assumedthatif Josephus had access to revenuefigures he may also have had access to census records. Frankly, I am astonished that Jones (1948) 10 consideredJosephus'estimateto be the sole reliable figuresurviving in literary sources forthe totalpopulation of an ancientsociety. 27 Beloch, Bevolkerung 257, interpreted xoaO' ipg&; as referring not to Diodorus' own day but rather to the date of his principal sourceforthe pharaonic period, Hekataios of Abdera; however,Walek-Czernecki, (above, note 2) 10-11, has demonstrated thatthis interpretation is untenable.Diodorus Siculus' sources for this passage are discussed by A. Burton,Diodorus Siculus, Book I: A Commentary (Leiden 1972) 6-9. Wilckenarguedin support of the textual emendation: see O.Wilck. I 487. For a hypotheticalassessment of the demographic developmentof Egypt from pharaonicthrough Islamic timesbased on the amountof cultivableland, see K. W. Butzer,Early HydraulicCivilizationsin Egypt:A Studyin Cultural Ecology (Chicago 1976). 28 See note 2 above, 10-11; cf. Delia, Roman Ale-xandria 21-23.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

284

Diana Delia

nature of theseregisters and thescope of theterm EX&OFpotare uncertain.29 'EXFviOFpot cannot possiblysignify onlyfreemalecitizens, sincewerewe to treble thisfigure to allow forone wifeand a minimum of one childpercitizen thetotalfreecitizenpopulation family, one million, wouldamount to nearly without even taking intoaccounttheextensive foreign resident population or slaves. On the otherhand,if the termsignifies all freemales residingat Alexandria regardless of civicstatus, then a minimum total of more population thanone millionresidents would stillresult after allowingforone wifeand childeach as wellas slaves.Bothsumsareexcessive for a city whoseareawas only six-tenths the size of third-century Rome.30 Accordingly,300,000 FXEciOcpot mostprobablyrepresents an approximate totalforAlexandrian citizensof bothgenders and all ages, although it is uncertain all of whether these actuallyresidedwithinthe city limitsor were merelyregistered at Alexandria and resided throughout Egypt or abroad.31 In addition, thesources reveal thatforeign residents were numerous at Alexandriathroughout the Ptolemaic and Romaneras butit is impossible to estimate their numbers; nor can proportions ofEgyptians andslavesinthecity be advanced with anydegree of accuracy. I wouldbe verysurprised Nevertheless, ifthetotalpopulation of RomanAlexandria everexceeded therange of500,000to600,000persons.32 In a paperdelivered at theXVIII International Congress of Papyrologists, Mostafa el-Abbadi valiantly attempted to estimate thepopulation ofAlexandria the late first during century B.C. and thesixthcentury A.D. He interpreted Diodorus' figureas signifying the freeresident populationof Alexandria inclusive of citizenand foreign men,womenand children.33 On themodelof Westermann,34 el-Abbadiadded an extra25 to 30 percent of thisfigure for slaves,arriving at a totalpopulation of Alexandria circa60 B.C. that ranged between 350,000and 375,000persons. However, thistotal does notcompare at all favorablywith el-Abbadi's estimateof 525,000to 600,000 persons forthe population of Alexandria in thesixth century A.D., whilethelatter also derives fromtenuousassumptions thatresultfrom combining sourcesfrom remote chronological contexts.

29 Nor has a search for of Diodorus iXFVOcpo; in the historyand fragments Siculus in theTLG elucidatedDiodorus' use of thisterm. 30 Meier (above, note 22) 329. 31 Diodorus' estimateof the Alexandriancitizen populationwould have been facilitated by the fact thatcitizensof the Greek cities in Egyptwere requiredto report births of theirchildren. See Delia, Roman Alexandria47 and 83, and H. I. Bell, "Diplomatica Antinoitica," Aegyptus13 (1933) 518-22. 32 Strabo (16.2.5) characterizedSeleucia on the Tigris and Alexandria as comparable in terms of v6cvagt; (strength, i.e. of manpower) and p.&yeOo; (magnitude, physicalsize). The elder Pliny subsequently relatedthatin his day, circa A.D. 60, the population of Seleucia reportedly numbered600,000 (NH 6.30.122). See also Beloch, Bevolkerung, 479. 33 "The Grain Supply of Alexandriaand its Populationin ByzantineTimes," (Athens 1986). 34 See above, note 22.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ThePopulation ofRomanAlexandria

285

El-Abbadiassumedthat of grain extorted medimni thetwomillion by the prefect of Egyptfrom theAlexandrian dole in A.D. 546 represented grain the entire dole, although thetextof Procopius(HA 26.41-3) does notimplythat this was the whole but merelyrelatesthattwo millionmedimniwas the amountof grainwhichthe prefect, Hephaestus, pocketed.El-Abbadi next advancedtheargument thata totalgraindole of two millionmedimniwas in thesixth distributed century at theone artabaperperson ratedocumented in A.D. II/III,so that there were300,000recipients of thegrain dole. Finally, elAbbadi assumed thatthe dole was distributed among all adult residents, regardless of gender or civic status, by extending thegeneric phrase tXfOo; of EusebiusHE 7.21.9 to oi tE acpcxKovoTrxat Kou. gc?Xpt T6OV oiKiyUopcov of the sentencewhichfollows,although the latter LF36oPi8jKovtca probably signified male recipients exclusively of theRomangrain dole in A.D. 261. In conclusion, el-Abbadi projected a total population of 525,000to 600,000 range persons at Alexandria during thesixth A.D. based on theassumption century thatmales and femaleswereevenlyrepresented on thedole, whichyielded 150,000adultmales,and by adopting Duncan-Jones' ratioof adultmales = 28.6% of thefreepopulation.35 Nonetheless, it wouldbe mostunusualforthe population of Alexandria, reduced byendemic racialhostilities andwarsduring theRomanprincipate, to have doubledby the sixthcentury.Recently, the assumption that after a waror natural disaster has reduced a population, it will replenish itself to itsformer size,provided that no newcatastrophe occurshas beenchallenged. Onlya conservative growth rate canbe demonstrated.36 Figuresforthepopulation of Alexandria at thetimeof theArabconquest (A.D. 642) are preserved in theaccounts of severalArabsources.The Futuh Misrof 'Abd al-Hakamrelates that according to one source, 'Amrreported to Omar thathe had found40,000 Jews at Alexandriapaying taxes.37The schematic sequence of 4,000 baths,40,000 Jewsand 400 royalpavillions, however, cautions one against placing excessivetrust in thesefigures. 'Abd alHakamgoes on to relate that other sources said that 70,000Jewsat Alexandria wereapprehensive, and that there were200,000Byzantine (literally,"Roman") men,30,000 of whomalong withtheir families and possessionsabandoned Alexandria. Finally,'Abd al-Hakamrelates that 600,000 malesat Alexandria weresubject tothecapitation tax. With respect to thetax,TheKhitab al Khitat ofal-Makrizi notesthat 'Amrlevieda taxon all Jews at therateof2 dinars per head,exempting onlyelderly men, children whohadnotreached maturity, and women;38 butwhat ofChristians, whowererequired topaythistaxas well?AlBaladhuri related that at thetimeof 'Amr'sconquest, thecapitation tax from

35 Economy,264 note 4. 36 M. Hansen, "Demographic Reflections on the Numberof AthenianCitizens, 451-309 B.C.," AJAH 7 (1982) 173-76. 37 The History of the Conquestof Egypt, NorthAfricaand Spain known as the Futuh Misr of Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam, ed. C. C. Torrey. Yale Oriental Series, ResearchesIII (New Haven 1922) 82 (Torrey). 38 MIFAO 3 (1906) 126-28, tr.P. Casanova.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

286

Diana Delia

to 180,000dinars, Alexandria amounted which that suggests 90,000hadrefused to embraceIslam.39 To be sure,thefigures in thesesourcesare preserved and thoseof greater on the contradictory, magnitude maywellexcitesuspicion grounds thattheglorious tradition of theArabconquest of Alexandria would havebeenenhanced byexaggerating thesize ofitscaptive population.40 One fragment ofthenotorious ActaAlexandrinorum warrants consideration in connection with ourdiscussion In P. ofthepopulation ofRomanAlexandria. Giss. Univ. V 46, the figure180,000 appearsin theline whichfollowsthe mention of 173 elders. VonPremerstein restored thetext ofcolumn I toread:

"AKoucyov Rau, Kac]cap.

?ORtUg,

p?

'O 6i?'ov yova6'cov aU]Toi a&xap?vo; ETiE(V).

'AXiEXav6p"o)v O toax7oKp6p,

Yc-pO[Vrct']V,

6ijO;

Xitdt;i

1&11

0 ?V

7cpoAxCY]a&i'6 so7

tX?po1CV]

AV6&p 6]ocKx Kat OxiCOt gpui&x[;

N.4

7E?ptEXO1U-1

Recently, L. Koenentranscribed thetext as follows: &ov CU4]oi 'aya'vos; EtRE(V). 'O &% yov )CUpt Kai]'ap. [o? 9AXc?Xav6ptwv Kcalrq7OpCO, i ?rj. c]pl? cxroKpaircp p?0Opx0a( ?) jtki; a9LboP-j ?yp0[V'rO]V,

lzo-

RtXo;ijO; 1 61 tp

CiKc c

clvat 'r]

2tX k0iO, 'r 6&

PKX~6?

toM&4

itnV]42

Notwithstanding thedifficulties in attempting encountered to restore so badlydamageda text, at besthypothetical due to theabsenceof parallels, both von Premerstein and Koenenhaveargued that 6]?KicaKi OKtro gopup&a[; can onlyrelate to thepopulation ofAlexandria, presumably at thecloseofTiberius' reignand theaccessionof Gaius in A.D. 37.43 To be sure,6]t?xa icKa 0ic'rh

39 Kitab Futuhal Buldan,tr.P. Hitti(Bierut1966).

Years of the Roman Dominion2 (Oxford 1978) 310-27 and 368-400. The extant remainsof Arab walls in the Shalalat Gardens and south of the Kom el-Dikka fortress indicatethatthese enclosed an area considerably smallerthanin Roman times. 41 P. Giss. Univ. V 46, ed. A. von Premerstein, see note 2 above; this document has been re-edited as P. Yale II 107. Von Premerstein's reconstruction of the texthas earnedboth praise and censure:H. I. Bell, CR 54 (1940) 48-49; H. A. Musurillo, The Acts of thePagan Martyrs (Oxford1954) 106; H. C. Youtie, CW 54 (1943) 163-65 = Scriptunculae (Amsterdam1973) II 863-67. On the gerousia at Alexandria, see M. el-Abbadi,"The Gerousia in Roman Egypt," JEA 50 (1964) 164-69. 42 See above, note 2. 43 Von Premerstein believedthattheTiberius, referred to in columnsI and II of this document,was Gemellus and accordingly dated the firstaudience prior to

40 In general,see A.J. Butler,The Arab Conquestof Egyptand the Last Thirty

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Population ofRomanAlexandria

287

appeal. If 180,000 connected withthesubjectunder opii6ca[; is intimately werein question, drachmai(theequivalent of 30 talants) we are at a loss to thefigure did not appreciate thesignificance of thissum; likewise, probably in connection witha local alimentary refer to artabai of graindistributed intervention in suchmatters sincetheearliest evidence of imperial scheme, (in Italy, nottheprovinces) of Nervaand Trajan.If thisfigure datesto thereigns indeed refers topersons, be? whocanthey Von Premerstein datea nwnerus andKoenenargued that claususof bythis 180,000male citizens had been established at Alexandria and that thisfigure should be associated withthe tribalschemaof P. Hib. I 28 (265 B.C.);44 accordingly, forthe totalpopulation theyprojected estimates of Alexandria thereign of Gaius.Nevertheless, of a numerus during thevery clausus concept of citizensis unacceptable, because it is grounded on theassumption thatthe number of citizens remained fixed regardless of whether thecitizen population actually experienced or decline.I do notknowofa single demographic growth parallel as I haveargued amongGreek citiesin theRomanempire.45 Moreover, elsewhere, P. Hib. I 28 maywellrefer to thetribal or organization at Ptolemais Naukratis during thethird century B.C., andnottoAlexandria.46 t One possibility O hitherto notconsidered is that ]Eiccica oK Wpt&&x[; represents thenumber ofJews resident at Alexandria anditsimmediate environs. For Josephus related that50,000 (butby no meansall) of theJewshad been massacred in theDelta district of Alexandria in A.D. 61, pursuant to theorders oftheprefect Tiberius luliusAlexander (BJ 494-98).One generation earlier, the Alexandrian Philohadclaimed that one million Jews resided inEgypt (in Flacc. 43).47 To be sure,theaccuracy of Philo's estimate as an absolutefigure, like ofJosephus that forthetotal population ofEgypt discussed earlier, is subject to doubt; thesemay, however, suggest that Jewsstoodinapproximately a 1:7ratio to thetotalpopulation of Egypt.Moreover, one wouldexpectthat thelargest concentration ofJews occurred inthecity ofAlexandria. It is undoubtedly truethatJewish and Alexandrian polemic may have exaggerated theaccounts oftheendemic civilstrife which tookplaceduring the reigns of Gaius and Claudiusbetween Alexandrians and Jewsresident in this city. Philo's in Flaccum and Legatio ad Gaium,the historical acountsof Josephus, and theemperor Claudius'response preserved as P. Lond. VI 1912.

Gemellus' suicide towardsthe end of A.D. 37. However,it is indeed likely that the emperor Tiberiuswas meant,the first audiencehavingtakenplace beforehim at Capri and the second audience occurring beforeGaius at Rome after Tiberius' death in March A.D. 37. See thediscussionin P. Yale II 107, p. 86. 44 Von Premerstein, 46-47; Koenen,2. See also Fraser, PA I 39-40. 45 To be sure,SEG IX 1 (Cyrene,reign of PtolemyI) preservesthe textof a constitution imposed on Cyrene which established a politeuma limited to ten thousand citizens;this constitution may have been imposedas earlyas 321 B.C., but it is uncertainhow long it remained in effect.The Cyrenaean edicts of Augustus (SEG IX 8-9, Cyrene,7/6a)do not mention a closed body of citizens, but focus insteadon the distinctions betweenRomancitizensand Hellenes. 46 Delia, RomanAlexandria80-82. 47 Cf. Leg. 124, 256 and 350.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

288

Diana Delia

Jewshad citizens and resident Alexandrian (Philadelphia, A.D. 41) relatethat in thecity and privileges repeatedly come to blowsovertheir respective rights on several theseissueswerethesubject and that, ofappealsdirected occasions, circumstances similar to theemperor.Accordingly, it is justpossiblethat led inP. Giss. Univ.V 46, preserved to theembassy forposterity as one described Acta Alexandrinorum; episode in theardently nationalistic and anti-Roman it was intended to inflameAlexandrian passions and solidarity by means of what critics denouncing perceived as Rome'sphilojudaic proclivities. Withthetotal population ofAlexandria between probably ranging 500,000 and 600,000 personsduring theRomanprincipate, 180,000Jewswouldhave represented 30 to 36 percentof the whole. If one accepts this figure, an of Jewsresidedat Alexandria, whichwould extraordinarily largeproportion explain why this city experiencedrepeatedviolentoutbreaks betweenits HellenicandJewish factions.48 Alternatively, one might also dismiss thefigure of 180,000 ifindeeditemanated Jewsas suspect, from propaganda to designed an alleged exaggerate Jewish threat tocitizens ofAlexandria. In termsof manpower, casualty and captive figuresin the Bellum Alexandrinum are nothelpful, insofar as a generallevyhad been conducted throughout Egypt to meetthedemands of thewar(Bell. Alex.2). Nordoes this sourcedisclosetheamount offoodrequired to feedtheAlexandrian population undersiege, howeverinflated its numbers may have been as a resultof recruitment in theDeltaandUpper Egypt.49 There appears tohavebeenan annonaatAlexandria during thethird century A.D., theinstitution of which mayhavecoincided with thefirst appearance of Five in number (one percity district), thesemagistrates replaced cUiOivt6pXt. theformer ?in rij; ciOiivt&;and wereresponsible fortheregulation of prices

For a ratio of 70,000 Jewsto 200,000 Byzantines(presumably all males) at Alexandriaat the timeof theArab conquestnote thediscussionabove. 49 The classic studywhichtriedto estimate a population based on the totalfood supplyof a city is thatof W. J. Oates: "The Population of Rome," CP 26 (1934) 101-16. Oates presupposed thatthe food consumption of a humanindividualhas a constantaverage,regardlessof geographicsituation or the caloric demandsof various professions.Moreover,he disregardedthe significant difference in the amountsof monthly rationscited by ancientauthorities, whichvary from4 to 5 modii per month, or 20 to 20%. He ignoredthe disparity of occupationsof the intendedrecipientsand also did not take into considerationthe fact that the weightsof various grains considerablydiffer. Cf. A. Jarde,Les cereales dans l'antiquite grecque (Paris 1925) 128-44; Packer, "Housing and Population" (above, note 17), 87-89; C. Clark and M. Haswell, "Food Consumption," in The Economics of Subsistence Agriculture4(London 1970) 1-26; and G. D. R. Sanders, "Reassessing Ancient Populations,"ABSA 79 (1984) 251-62. For an ordinary grainallowanceof one artaba (= 4 modii) per slave or laborerin Roman Egypt,see Johnson, Roman Egypt(above, note 26) 301 and the documents cited therein. The total food consumptionof Roman Alexandria is in any case unknown.

48

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ThePopulation ofRomanAlexandria

289

theacclamation and thefoodsupply.50 Circa A.D. 261, after of theEgyptian praefect M. Julius Aemilianus by theAlexandrian populaceand theEmperor Gallienus'measures tocapture theusurper andrecover theprovince, Alexandria was laid waste.Eusebiuspurportedly theaccount ofBishopDionysios preserves of Alexandriawhichdescribesthe slaughter and resulting pestilence(H.E. 7.21.9). In these direcircumstances, all malesbetween theages offourteen and eighty years wereeligible for theAlexandrian arepregrain dole;butno figures served for thetotal number ofrecipients.5' Another approach which has hitherto beenunexplored might be basedon a correlation of thewaterstorage in theRoman capacity withthedevelopment periodof thevastnetwork of canalsand cistems whichundermine theancient cityof Alexandria. It nevertheless appearsimpossible to estimate theaverage amount of waterconsumed in lightof theextensive by an individual use of water for publicandprivate baths, household needs, andfor beasts ofburden and livestock. Moreover, although theearlynetwork of canals and cisterns was probably designed to anticipate future needs,we maynever be sureaboutthe extent to whichsubsequent additions satisfied or surpassed therequirements of thecuffent population.52 Finally, the modernhistorian oftenfails to appreciatethe fact that populationfiguresare, afterall, only roughestimates. Numerousfactors constantly modified thesefigures; amongthem werelocal conditions, elective population controls, and emigration of Alexandrians intotheEgyptian Chora and abroad.Conversely, in view of thesplendid libraries and Museum, a fine reputation fortraining in philosophical, medical,and, eventually, Christian studies, and itsdistinct commercial advantages, Alexandria attracted scoresof foreignimmigrants as well. Moreover,we mustnot forget the pattern of

50 Delia, Roman Alexandria 158-59; cf. Breccia, IGA 71 (Alexandria,A.D. 158). Note Johnson'ssuggestion (above, note 26, p. 19) thatc6Onvt6apXat may have been appointed to regulatethemarket and food supplyin timesof scarcity 51 A minimum figure forthe Byzantine annona is preserved by Procopius,who relates thatduringthe reign of Justinian, the Alexandrianswere deprivedof as many as two million measures of grain from their annona allotmentby a dishonest governor (H. A. 26). What proportion this represented of the whole annona and how manypeople the rationwas intended to subsidize are unknown; see above, 283. On theuse offrumentationes and congiaria to estimate the population of Rome, see Hopkins(1978) 97. 52 On thenetwork of subterranean canals and cisterns fed by the Nile, see Bell. Alex. 5 and IGRR I 1055; cf. G. Botti, "Les citernesd'Alexandrie,"BSAA 2 (1899) 15-26, and L. Dabrowski,"La citerne'a eau sous le mosquee de Nabi Daniel," AlexandriaUniversity, Bull. FacultyofArts 12 (1958) 40-48. The huge el-Nabeh cistern on Sultan Hussein Street where the Shalalat Gardens begin appears to be Roman in origin, with considerable Byzantine renovation. However,R. P. Duncan-Jones has arguedthatthereis no way of estimating the amountof water used per person: "City Populationin Roman Africa,"JRS 53 (1963) 85.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

290

Diana Delia

of thecitypopulation.53 component &vaXcprjGt;whichswelledtheEgyptian of natural Other factors whichinfluenced population size weretheoccurrence by low Nile inundations, disasters suchas famine, especially thoseoccasioned pestilence,the recurrent riots and reprisalsby Hellenes and Jews alike of A.D. theJewish revolt throughout thefirst three centuries of theprincipate, Caracallain A.D. 115-16,themassacre of Alexandrian youths by theEmperor circa 215, and thedevastation of thecitybothat thehandsof Gallienus'army invasionand A.D. 261 and again in A.D. 268 pursuant to the Palmyrene forthepopulation of Roman occupation.54 Hence the maximum estimate is a mere approximation ofa Alexandria suggested herein-500,000-600,OOO-

53 On the average age at death in Roman Egypt, see M. Hombertand C. Preaux, CdE 20 (1945) 139-45. See also F. A. Hooper, "Data fromKom Abou Billou on the Lengthof Life in Greco-RomanEgypt,"CdE 31 (1956) 332-340; A. el-Sawy,J. Bouzek and L. Vidman, "New Stelae from theTerenouthis Cemetery in Egypt,"ArchivOrientalni48 (1980) 330-55; and Abd el-Hafeez abd el-Al, J. C. Grenier and G. Wagner, Stelesfune'raires de Kom Abu Bellou (Paris 1985). On the reasons for a high mortality level in cities of the Roman empire,see A. Scobie, "Slums, Sanitationand Mortality in the Roman World," Klio 68 (1986) 399-433. On ancientmodes of familylimitation, see K. Hopkins,"Contraception in the Roman Empire,"PSSH (1965) 124-51; cf. P. A. Brunt, Italian Manpower: 225 B.C.-A.D. 14 (Oxford 1971) 146-54. On Alexandrians in the Chora, see el-Abbadi, Alexandrians (above, note 2) 539-41 and 557-60. Undoubtedly numerous Alexandrians wentabroad to serve in the Roman armyor navy, as itinerant professionals (athletes, musicians,rhetors), or in connection with banking and commerce: see Seneca, Ep. 77.1, Strabo 2.5.12, 14.5.13, and 17.1.13. For Alexandria as an educational center,consult idem and AmmianusMarcellinus22.16.16-19; cf. Dio Chrysostom, Or. 32.40 on the cosmopolitan character of the Alexandrian populace. As at Athens, immigrants to Alexandria mightacquire citizenshiponly by special decree; hence the flow of immigrants into the city did not offsetthe emigration of Alexandrian citizens: Hansen (1982) 177. On avaX(prIcTt see R. P. Duncan-Jones, "Demographic Change and EconomicProgress," in Tecnologia, economia e societa nel mondoromano(Como 1980) 74. 54 Pliny,Paneg. 31-32, refers to a faminein Egyptduringthereignof Trajan. On the unpredictable floodingof the Nile, see: IGRR I.1290 (the Elephantine nilometer),and P. Oxy. HI 486.31-33 (A.D. 131). See also Pliny,NH 5.10.58, and D. Bonneau,La crue du Nil: divinite' e'gyptienne (Paris 1964). For pestilence, see HA: Verus 8.1 and Euseb. HE 7.21.9. See also G. Casanova, "La peste nella documentazione greca d'Egitto," Proceedings XVII InternationalPapyrological Congress (Naples 1983) 949-56, and "Epideme e fame nella documentazione greca d'Egitto,"Aegyptus64 (1984) 174-75. On the Jewish revolt,see A. Fuks, "The Jewish Revolt in Egypt (A.D. 115-117) in the Light of the Papyri," Aegyptus33 (1953) 131-58, and "'Aspects of the Jewishrevolt in A.D. 115117," JRS 51 (1961) 98-104; and M. Pucci, "La rivoltaebraica in Egitto (115117 d.C.) nella storiografia antica,"Aegyptus62 (1982) 195-217.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ThePopulation ofRomanAlexandria

291

variablewhichwould wax and wane in thecourseof thenextfourcenturies under Roman rule.55

55 I am indebted to RogerBagnall, WilliamV. Harris,Ludwig Koenen,Mostafa el-Abbadi,RuthScodel and the referees of TAPA fortheir carefulreadingof the manuscriptand their stimulatingcomments. My sincere thanks also go to JeanetteWakin, Edward Kamal and Mahmoud Helmi for their assistance in translating the textof 'Abd al-Hakam'sFutuhMisr. A 1983-1984 fellowship from the American Research Center in Egypt enabled me to study first-handthe topography and monuments of ancientAlexandria.

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

292

Diana Delia Figure1

2'3

~~~~1p~~~~~~~~~~

AR~~~~~~~~~~~Lx

This content downloaded from 188.26.205.145 on Fri, 26 Jul 2013 08:14:56 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Ernst Cassirer Et Al. - Some Remarks On The Question of The Originality of The Renaissance (Journal of The History of Ideas, 4, 1, 1943)Document27 paginiErnst Cassirer Et Al. - Some Remarks On The Question of The Originality of The Renaissance (Journal of The History of Ideas, 4, 1, 1943)carlos murciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Being and Hayah - ARIGA TetsutaroDocument22 paginiBeing and Hayah - ARIGA Tetsutarorio rio rioÎncă nu există evaluări

- BREMMER. Becoming A Man in Ancient Greece and Rome Essays On Myths and Rituals of Initiation. Tübingen Mohr Siebeck GMBH & Co. KG, 2021.Document296 paginiBREMMER. Becoming A Man in Ancient Greece and Rome Essays On Myths and Rituals of Initiation. Tübingen Mohr Siebeck GMBH & Co. KG, 2021.JordynÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mithraism and ChristianityDocument11 paginiMithraism and ChristianityIsrael CamposÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 Essence Accident and Race 1984Document12 pagini2 Essence Accident and Race 1984NeguePower LMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fulvius de Boer, "Criticism of A. Van Hooff, 'Was Jesus Really Caesar?'"Document16 paginiFulvius de Boer, "Criticism of A. Van Hooff, 'Was Jesus Really Caesar?'"MariaJanna100% (7)

- 2016 Tracy Davenport Thesis PDFDocument228 pagini2016 Tracy Davenport Thesis PDFJac StrijbosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamentals of Behavioral Statistics by Richard RunyonDocument664 paginiFundamentals of Behavioral Statistics by Richard RunyonAbraham Niyongere100% (1)

- SQQS1013 CHP04Document20 paginiSQQS1013 CHP04Ameer Al-asyraf MuhamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Return On InvestmentDocument13 paginiReturn On InvestmenttaufecÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient LibrariesDocument13 paginiAncient Librariesfsultana100% (1)

- Aalders, Rec. Fraser, Ptolemaic AlexandriaDocument4 paginiAalders, Rec. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandriaaristarchos76Încă nu există evaluări

- Ancient Philosophers On Language in Col PDFDocument12 paginiAncient Philosophers On Language in Col PDFJo Gadu100% (1)

- Afonasin Religious MindDocument11 paginiAfonasin Religious MindMarco LucidiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Confesion de San Cipriano PDFDocument36 paginiConfesion de San Cipriano PDFjeamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bremmer MythandRitual4 PDFDocument23 paginiBremmer MythandRitual4 PDFartemida_100% (1)

- Hades of Hippolytus or Tartarus of TertullianDocument23 paginiHades of Hippolytus or Tartarus of TertullianJAadventista100% (1)

- ContentDocument28 paginiContentPassent ChahineÎncă nu există evaluări

- 07 Lazarus TroublesDocument18 pagini07 Lazarus TroublesNishÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Manichaean Challenge To Egyptian ChristianityDocument14 paginiThe Manichaean Challenge To Egyptian ChristianityMonachus Ignotus100% (1)

- Philo's de Vita Contemplativa As A Philosopher's Dream - Engberg-PedersenDocument25 paginiPhilo's de Vita Contemplativa As A Philosopher's Dream - Engberg-PedersenGabriele CornelliÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Arians of AlexandriaDocument13 paginiThe Arians of AlexandriaPandexaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adolph Von Menzel - Historical and Literary Studies Pagan Jewish and Christian Cd6 Id471145024 Size80Document19 paginiAdolph Von Menzel - Historical and Literary Studies Pagan Jewish and Christian Cd6 Id471145024 Size80HotSpireÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mystical Union in Early KabbalahDocument2 paginiMystical Union in Early KabbalahIan H GladwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- L Redfield EssenesDocument14 paginiL Redfield EssenesFrank LzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece Jann. BremmerDocument23 paginiMyth and Ritual in Ancient Greece Jann. Bremmerkaren santosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Goodacre Mark 2021 How Empty Was The Tomb CompressDocument15 paginiGoodacre Mark 2021 How Empty Was The Tomb CompressJohn OLEStar-TigpeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 604270Document9 pagini604270Mohamed NassarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maximus of Tyre, What Divinity Is According To PlatoDocument6 paginiMaximus of Tyre, What Divinity Is According To PlatonatzucowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pythagoras Northern Connections Zalmoxis Abaris AristeasDocument17 paginiPythagoras Northern Connections Zalmoxis Abaris AristeasЛеонид ЖмудьÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manicheism I Intro PDFDocument65 paginiManicheism I Intro PDFBrent Cullen100% (1)

- Proclus and His Legacy - Danielle Layne, David D. Butorac PDFDocument460 paginiProclus and His Legacy - Danielle Layne, David D. Butorac PDFPricopi VictorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Encyclopedia of A Royal QueerDocument11 paginiThe Encyclopedia of A Royal Queersian017Încă nu există evaluări

- Aretaeus of Cappadocia and The First Description oDocument6 paginiAretaeus of Cappadocia and The First Description opepepartaolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samuel Rubenson - The Apophthegmata Patrum in Syriac, Arabic and Ethiopic. Status QuestionisDocument9 paginiSamuel Rubenson - The Apophthegmata Patrum in Syriac, Arabic and Ethiopic. Status QuestionisshenkeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Damascius, Simplicuis and The Return From PersiaDocument31 paginiDamascius, Simplicuis and The Return From PersiaFelipe AguirreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Birger A. Pearson, James E. Goehring Eds. The Roots of Egyptian Christianity Studies in Antiquity and Christianity 1997Document349 paginiBirger A. Pearson, James E. Goehring Eds. The Roots of Egyptian Christianity Studies in Antiquity and Christianity 1997Esperanza Smith100% (5)

- Matthew Dillon, Kassandra Mantic, Maenadic or Manic, Gender and The Nature of Prophetic Experience in Ancient GreeceDocument21 paginiMatthew Dillon, Kassandra Mantic, Maenadic or Manic, Gender and The Nature of Prophetic Experience in Ancient GreeceAla_Balala100% (1)

- The Īsāwiyya RevisitedDocument23 paginiThe Īsāwiyya RevisitedShep SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20140969Document27 pagini20140969Anton_Toth_5703Încă nu există evaluări

- Blenkinsopp, Deuteronomy and The Politics of Post-Mortem Existence 1535182Document17 paginiBlenkinsopp, Deuteronomy and The Politics of Post-Mortem Existence 1535182Ahqeter100% (1)

- DILLON Plato and The Golden AgeDocument17 paginiDILLON Plato and The Golden Agececilia-mcdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anatoliaantiqua 303 PDFDocument11 paginiAnatoliaantiqua 303 PDFschauerÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Apocalyptic Vision of Islamic HistoryDocument32 paginiAn Apocalyptic Vision of Islamic HistoryMohammad Pervez MughalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Original Doctrine of Valentinus The Gnostic PDFDocument27 paginiThe Original Doctrine of Valentinus The Gnostic PDFManticora VenerandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baker-Brian, Julian Apostate, BMCR Brynmawr Edu 2013 2013-04-24 HTMLDocument6 paginiBaker-Brian, Julian Apostate, BMCR Brynmawr Edu 2013 2013-04-24 HTMLMr. PaikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zaehner PDFDocument5 paginiZaehner PDFioan dumitrescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taylor On The Wanderings of UlyssesDocument22 paginiTaylor On The Wanderings of UlyssesPerched AboveÎncă nu există evaluări

- A New History of Libraries and Books inDocument48 paginiA New History of Libraries and Books inPhilodemus GadarensisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brills Companion To The Reception of Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism in The Middle Ages and The Renaissance (Ed. Irene Caiazzo)Document513 paginiBrills Companion To The Reception of Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism in The Middle Ages and The Renaissance (Ed. Irene Caiazzo)John Lorenzo HickeyÎncă nu există evaluări

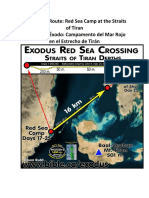

- The Exodus RouteDocument46 paginiThe Exodus RouteScienceÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASSMANN, Jan Solar DiscourseDocument17 paginiASSMANN, Jan Solar DiscourseLior ZalisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proclus Commentary On The Timaeus of Plato, Book OneDocument177 paginiProclus Commentary On The Timaeus of Plato, Book OneMartin EuserÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fisseha Jewish Temple in EgyptDocument13 paginiFisseha Jewish Temple in EgyptGeez Bemesmer-LayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutton The Patient's Choice A New Treatise by Galen. The Classical Quaterly, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1990. Pp. 236-257Document23 paginiNutton The Patient's Choice A New Treatise by Galen. The Classical Quaterly, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1990. Pp. 236-257Gerda GerdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greek Political Thought - Syllabus - SPRDocument5 paginiGreek Political Thought - Syllabus - SPRPaoRobledoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emergence of Gnostic-Manichaean Christianity As A Case of Religious Identity in The MakingDocument8 paginiThe Emergence of Gnostic-Manichaean Christianity As A Case of Religious Identity in The Makingnarayana assoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionDocument8 paginiThe Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionAankh BenuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patristic Views On Hell-Part 1: Graham KeithDocument16 paginiPatristic Views On Hell-Part 1: Graham KeithНенадЗекавицаÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raoul Mortley What Is Negative Theology The Western OriginDocument8 paginiRaoul Mortley What Is Negative Theology The Western Originze_n6574Încă nu există evaluări

- The Splendor That Was Egypt: A General Survey of Egyptian Culture and CivilizationDe la EverandThe Splendor That Was Egypt: A General Survey of Egyptian Culture and CivilizationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hegel JSRI 2011 PDFDocument24 paginiHegel JSRI 2011 PDFWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hannah and Her Sisters - Eng - 25fps - 1986Document29 paginiHannah and Her Sisters - Eng - 25fps - 1986Walther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Assistance and Transmodernism in Christ'S Activity: Anton AdămuţDocument15 paginiSocial Assistance and Transmodernism in Christ'S Activity: Anton AdămuţWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aquinas IndeterminacyDocument20 paginiAquinas IndeterminacyWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aquinas KnowledgeDocument21 paginiAquinas KnowledgeWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Watson Phantasia in de Anima 3Document15 paginiWatson Phantasia in de Anima 3Walther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wasserman Death SoulDocument25 paginiWasserman Death SoulWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allegory HomerDocument18 paginiAllegory HomerWalther Prager100% (2)

- Aristotle: Non-Contradiction and Unity in Metaphysics GammaDocument1 paginăAristotle: Non-Contradiction and Unity in Metaphysics GammaWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wasserman Death SoulDocument25 paginiWasserman Death SoulWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Watson Phantasia in de Anima 3Document15 paginiWatson Phantasia in de Anima 3Walther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law GreeksDocument36 paginiLaw GreeksWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- AristeasDocument56 paginiAristeasWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- SilenceDocument1 paginăSilenceWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teleological View in Aquinas' Five Ways of Demonstrating God's ExistenceDocument1 paginăTeleological View in Aquinas' Five Ways of Demonstrating God's ExistenceWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nemesius of Emesa, Human NatureDocument1 paginăNemesius of Emesa, Human NatureWalther PragerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap 1-5Document37 paginiChap 1-5Cedrick SuarezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marketing 4.0: How Technologies Transform Marketing OrganizationDocument11 paginiMarketing 4.0: How Technologies Transform Marketing OrganizationadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perpormance Aapraisal Maddi LakshmaiahDocument92 paginiPerpormance Aapraisal Maddi LakshmaiahVamsi SakhamuriÎncă nu există evaluări

- MSAIC Course Outline - Subject To RevisionDocument4 paginiMSAIC Course Outline - Subject To RevisionVinay KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marketing Research ProposalDocument3 paginiMarketing Research ProposalAshifur Rahman KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Advertisement On Consumer'S Buying Behaviour With References To Fmcgs in Southern Punjab-PakistanDocument9 paginiEffects of Advertisement On Consumer'S Buying Behaviour With References To Fmcgs in Southern Punjab-PakistanJennifer Lozada BayaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Session 3 DistribtionDocument61 paginiSession 3 DistribtionSriya Aishwarya TataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Signedoff EAPPG11 q2 Mod5 Writingreportsurvey v3Document57 paginiSignedoff EAPPG11 q2 Mod5 Writingreportsurvey v3Edson LigananÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparative Study of MicrofinanceDocument5 paginiComparative Study of MicrofinanceHira RajpootÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spatial Analysis of Urban Poverty in Tehran MetropolisDocument18 paginiSpatial Analysis of Urban Poverty in Tehran MetropolisSANAMBIENTAL S.A.SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Whiskas Cat FoodDocument16 paginiWhiskas Cat Foodjaddan bruhnÎncă nu există evaluări

- General Education Teachers' Perceptions of Behavior Management and Intervention StrategiesDocument17 paginiGeneral Education Teachers' Perceptions of Behavior Management and Intervention StrategiescacaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal 2 MeliDocument13 paginiJurnal 2 MeliKholifatu UlfaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ChurchBurkeFutureofOrgsandODODP 2017493 PDFDocument10 paginiChurchBurkeFutureofOrgsandODODP 2017493 PDFShobha SheikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Related Study 7 Hyflex LearningDocument24 paginiRelated Study 7 Hyflex LearningJayson R. DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 PB PDFDocument115 pagini1 PB PDFvalentinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Methodology MCQ (Multiple Choice Questions) - JavaTpointDocument25 paginiResearch Methodology MCQ (Multiple Choice Questions) - JavaTpointkaranvir singhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Qualitative Data AnalysisDocument18 paginiQualitative Data Analysisbsunilsilva100% (2)

- Statistical Quality ControlDocument7 paginiStatistical Quality Controlaseem_active100% (1)

- A Time Series Analysis of Structural Break Time inDocument6 paginiA Time Series Analysis of Structural Break Time inCristina CÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internal Environment - SWOT - Q9-Q10Document9 paginiInternal Environment - SWOT - Q9-Q10anniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis 2022-2023 New1Document18 paginiThesis 2022-2023 New1Iamche MaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research IIDocument42 paginiResearch IIChristine Jean CeredonÎncă nu există evaluări

- By: Prof. Radhika Sahni Binomial DistributionDocument23 paginiBy: Prof. Radhika Sahni Binomial DistributionYyyyyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baseline TOR FinalDocument12 paginiBaseline TOR FinalAsnakew LegesseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teachers' Perceptions of Principals' Instructional Leadership Roles and PracticesDocument12 paginiTeachers' Perceptions of Principals' Instructional Leadership Roles and PracticesRon ChongÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study On Consumer's Attitudes and Satisfaction Towards Advertisement On Himalaya Products in Tirunelveli DistrictDocument9 paginiA Study On Consumer's Attitudes and Satisfaction Towards Advertisement On Himalaya Products in Tirunelveli DistrictRashmita BeheraÎncă nu există evaluări