Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cheating

Încărcat de

Camila Berríos MolinaDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cheating

Încărcat de

Camila Berríos MolinaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE

177

The Cheating Heart: Scientific Explorations of Infidelity

Stephen M. Drigotas 1 and William Barta

Department of Psychology, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas

Abstract Given the potential negative ramifications of infidelity, it is not surprising that researchers have attempted to delineate its root causes. Historically, descriptive approaches have simply identified the demographics of who is unfaithful and how often. However, recent developments in both evolutionary and investment-model research have greatly furthered understanding of infidelity. The field could gain additional insight by examining the similarities of these prominent approaches. Keywords infidelity; extradyadic behavior; relationships Infidelity, in the context of a dyadic relationship, represents a partners violation of norms regulating the level of emotional or physical intimacy with people outside the relationship. Marital infidelity is a leading cause of divorce, spousal battery, and homicide (e.g., Daly & Wilson, 1988). Despite the obvious personal and societal impact of infidelity, little empirical research examined its dynamics until the late 1970s. At that time, empirical researchers paid increased attention to this phenomenon, presumably because of their changing attitudes. Glass and Wright (1977) observed that prior to the 1970s, infidelity was subsumed under the category of sexually deviant behavior. The increasing visibility of infidelity and growing acceptance of nontraditional families during the 1970s,

and a willingness to acknowledge the sheer prevalence of infidelity, served to usher in the perception that risk factors for infidelity are pervasive across nominally exclusive heterosexual relationships. In this article, we summarize relevant empirical research, highlighting some of the key findings and theoretical perspectives that have emerged, particularly since the 1970s. Additionally, we identify new research directions.

THE DESCRIPTIVE APPROACH This approach encompasses largely atheoretical efforts to document the demographics and attitudinal correlates of infidelity. Typically, descriptive research relies on retrospective and self-report data. Kinsey and his associates found, for example, that 36% of husbands and 25% of wives reported having been unfaithful (e.g., Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin, & Gebhard, 1953). A more recent survey, spanning five age cohorts, found that 37% of men and 12.4% of women born between 1933 and 1942 reported having been unfaithful; among individuals born between 1953 and 1974, the figures were 27.6% for men and 26.2% for women (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). Gender differences in motivations for infidelity indicate that marital dissatisfaction tends to be higher among unfaithful women than unfaithful men, and that unfaithful men are more likely to re-

port a sexual rather than emotional motivation for infidelity (e.g., Glass & Wright, 1985). This distinction between emotional versus sexual motivation is reflected in the finding that a males infidelity is more likely than a females to be a one night stand, to involve someone of limited acquaintance, and to include coitus (Humphrey, 1987). Gender is also a factor in the likelihood of seeking divorce as a consequence of a partners infidelity. Shackelford (1998) asked people to rate the attractiveness of their partners (mate value) and indicate their own anticipated responses to infidelity. Results indicated that men were more likely than women to see infidelity as a reason for divorce. However, the likelihood of a woman (but not a man) seeking divorce covaried with the discrepancy between partners reported mate values (i.e., to the extent that a female partner was more attractive than her spouse, she was more likely to end a relationship following her partners infidelity). Women also appear to have broader criteria for their definition of infidelity, being more likely than men to end a marriage if their spouse dates or flirts with someone else, even if sexual intercourse does not occur. The observed increase in the frequency of married women being unfaithful may be due to the increasing percentage of women who work outside the home. Opportunity is a contributor to the likelihood of infidelity, and women who work outside the home have greater opportunity to form opposite-sex relationships than do women who stay at home. In addition, as women achieve greater economic independence, marital instability tends to increase (e.g., Humphrey, 1987). Some caution is necessary, however, when relying on self-reported infidelity to draw conclusions. Historically, social sanctions against

Copyright 2001 American Psychological Society

178

VOLUME 10, NUMBER 5, OCTOBER 2001

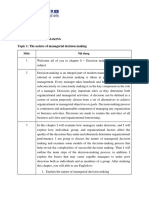

female infidelity have been far Buunk and Bakker (1995) found e.g., dating another person, being more severe than sanctions against that injunctive and descriptive alone), and investments (things the male infidelity (e.g., Daly & Wil- norms independently influence the individual would lose if the relason, 1988). The apparent increase likelihood of extradyadic sex, but tionship ends, e.g., shared possesin female infidelity, therefore, may descriptive norms typically outsions, friends). Research has dembe an artifact of a decline in the se- weigh injunctive norms. onstrated the models power in The normative model extends toa variety of imporverity of these sanctions rather accounting for than reflecting a true change in the sex roles. Sexual conquest is a comtant behaviors in relationships, inrate of infidelity (i.e., women may ponent of the masculine sex role cluding breaking up, willingness to be more likely to report truthfully (e.g., Lusterman, 1997). This may sacrifice, accommodation (the abilnow that society is more permis- account for the fact that historically ity to respond to the partners bad sive). Self-reports are also subject rates of infidelity have been higher behavior constructively), and derofor married men than for married to biases relating to the respongation of alternatives (the tendency dents level of trust in the confiden- women, and for the fact that men to make attractive others seem tiality of the survey, whether the are more likely than women to be worse than they actually are). In reference to infidelity, comspouse is present in the room, and unfaithful even if marital satisfacmitment may serve as a macromowhether the infidelity is known to tion is high. Furthermore, injunctive tive, that is, a central motive that the partner. Laumann et al. (1994) norms against both female infidelity guides both long-term and shortfound that individuals whose mar- and female sexual autonomy have term behavior. Highly committed riages were intact were markedly historically been far more strict, and individuals are less likely to be unless likely to report a history of infi-accompanied by more severe social faithful because they are motidelity than individuals whose mar- sanctions, than the corresponding vated to (a) derogate potential alnorms for men (e.g., Daly & Wilson, riages had ended. ternatives in order to protect the 1988). At the same time, the decline relationship (thus, effectively in male participation in extradyadic keeping alternatives unattractive) sex observed over the course of the THE NORMATIVE and (b) consider, when tempted to 20th century may reflect changing APPROACH be unfaithful, the long-term ramiattitudes toward male sexual entifications of such behavior on the tlement and conquest. Like the descriptive approach, relationship and the partner. Thus, the normative approach has tended commitment serves to both reduce to rely on self-report data and retrothe frequency with which temptaTHE INVESTMENT-MODEL spective accounts. The key distinctions arise and provide resources APPROACH tion between the two approaches is enabling the individual to shift his that normative researchers proceed or her focus from any potential The investment model (for a refrom the hypothesis that the likelishort-term pleasure to the longview, see Rusbult, Drigotas, & Verhood of engaging in infidelity can term consequences. In a direct test of the models be attributed to societal norms. For ette, 1994) represents a theory reability to predict infidelity (Driggarding the process by which example, people are more likely to otas, Safstrom, & Gentilia, 1999), individuals become committed to be unfaithful if they are acquainted measures of commitment (and of their relationships, as well as the with someone who has been unother constructs in the model) circumstances under which feelfaithful than if they have no acsuccessfully predicted subsequaintances who have been unfaith-ings of commitment erode and requent infidelity in dating couples lationships end. According to this ful (Buunk & Bakker, 1995). Norms both over the course of a semester model, the primary force in relarelating to infidelity can be categoinjunctive or descriptive and over spring break. This retionships is commitment, which is rized as (Buunk & Bakker, 1995). Injunctivea psychological attachment to, and search was important for a varinorms are the formal laws and mo- a motivation to continue, a relaety of reasons: First, it demonres that a society upholds, whereas tionship. Forces that serve to make strated successful prediction of descriptive norms refer to percep- an individual more or less commitactual behavior, rather than relytions of other peoples behavior. Reing on the traditional method of ted to a relationship include satissearch indicates that individuals are faction (how happy the individual asking individuals post hoc why more likely to engage in a prohib- is with the relationship), alternathey were unfaithful. Second, it ited activity if they see someone else provided additional support for tive quality (potential satisfaction violating the same prohibition. the breadth of the investment provided outside the relationship,

Published by Blackwell Publishers Inc.

CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE

179

model. Third, disparate their methods biological parentage, whereas during their most fertile days, and (survey vs. diary) yielded females the do. As a result, men are use contraceptives more consciensame findings. more likely than women to exhibit tiously with their marital partners violent sexual jealousy (e.g., Daly than with their extramarital part& Wilson, 1988). Women, freed ners (Baker & Bellis, 1995). from anxieties surrounding the biTHE EVOLUTIONARY ological parentage of their offAPPROACH spring, are instead alert to the posNEW DIRECTIONS sibility of male abandonment, The evolutionaryinasmuch approach,as like this abandonment rethe investment model, emphasizes sults in the decreased survivability Each of the approaches to the study of infidelity has focused on the exchange of benefits within the of their offspring. A third assumption evolu- characteristics of the theof structural dyad and predicts that satisfaction tionary psychologists is that parendyad, including the quality of the is largely dependent on the level of tal investment , or the time and repartners interactions, the exequity in this exchange. Evolutionsources devoted to offspring, change ofis resources, and the attracary psychologists also acknowledge inversely correlated tiveness with mating efof alternatives, and has that satisfaction is inversely related fort , or the time and resources deoverlooked the unique personalito the quality of alternatives. The voted to seeking out and attracting ties of the individuals involved. evolutionary model is distinHowever, personality dimensions guished, however, by its assump- sexual partnersincluding extradyadic partners. Because of the ines(e.g., narcissism) can be expected to tion that the functional basis of these influence perceived satisfaction benefits is not to promote satisfac- capable costs associated with geswithin a dyad and hence moderate tion but to facilitate the production tation and nursing, parental individuals degree of commitment of offspring. From a Darwinian per-investment is higher for women to their relationship (e.g., Lusterspective, both morphological and than for men. Consequently, men man, 1997). Consideration of indibehavioral characteristics of a spe- have more time and resources than vidual differences could improve cies are assumed to confer advan- women to devote to mating effort. both investment and evolutionary tages upon the organism in terms ofAs a result, at any given time, comreproductive success (RS). The to mates is petition for access models. For example, individual its measure of RS, in turn, is whether greater among males than among differences may account for why the individual produces offspring females, and this allows females to many females engage in sexually who themselves reproduce (e.g., be more discriminating than males motivated infidelities even though, Buss, 1998). Heterosexual behavior,in their choice of partners. as noted earlier, this does not diOne contribution rectly of theaffect evoluevolutionary psychologists argue, is their RS. Additional tionary perspective has been to shaped by oftentimes unconscious dimensions of individual differpredispositions functioning to pro- generate research answering quesences may serve to influence both tions that have not received attenmote an individuals RS. expectations regarding ones priOne assumption of evolutionary tion previously. For example, it has mary relationship and the assessment psychologists is that men and been found that men are more of the risks and rewards associated women do not possess the same likely to engage in sexual infidelity with an extradyadic relationship. One common criticism of infimotivation to cheat. A man can in- than in emotional infidelity and delity research is its overreliance crease his RS considerably by im- consider sexual infidelity to be on self-report methods. Notable for pregnating an extradyadic partmore upsetting relative to emoits methodology is a study by Seal, ner, whereas once a woman is tional infidelity than women do Agostinelli, and Hannett (1994). pregnant or has exclusive access to (e.g., Buss, 1998). Women who enUsing a sample of couples in exclua male, there is little benefit to her gage in casual sex with no intensive dating relationships, the remating with an extradyadic part- tion of having a lasting relationship searchers provided each member ner (e.g., Buss, 1998). She can still or children nonetheless show a of each dyad with an opportunity benefit from infidelity, however, if preference for partners who posto surreptitiously make a date with it is advantageous in terms of sess qualities they associate with an extradyadic partner. The retrading up to a superior mate. being a good parent (e.g., Buss, A second assumption of Women evolu- experience heightsearchers also measured partici1998). tionary psychologists revolves pants tendency to dissociate sex ened levels of libido during the . Males around paternal certainty and love and to seek sexual variety most fertile phase of menstruation, never have absoluteare certainty of to be unfaithful (i.e., sociosexuality). Both these most likely

Copyright 2001 American Psychological Society

180 tendencies were correlated with the likelihood of pursuing an extradyadic contact. Interestingly, although men were more likely than women to report a willingness to seek extradyadic contacts, the behavioral measure of actual extradyadic sexual encounters showed no difference between men and women. Innovations in methods, such as the diary method (e.g., Drigotas et al., 1999) or the introduction, in a controlled setting, of an opportunity to be unfaithful (Seal et al., 1994), may allow researchers to overcome participants biases in reporting their own previous behavior. Greater reliance on behavioral as opposed to subjective data is needed to corroborate and extend existing findings. The evolutionary model would benefit tremendously from longitudinal research focusing on the frequency of coitus both within and outside the primary relationship. In this age of contraceptives, coital frequency is the best index of RS. Thus, it would strengthen the general evolutionary perspective if data showed that coital frequency within the primary relationship initially declines when a man is unfaithful but eventually returns to an optimal level as coital frequency in the secondary relationship declines. These data would also shed light on whether sexual motivation is truly more characteristic of unfaithful males than unfaithful females.

VOLUME 10, NUMBER 5, OCTOBER 2001

Finally, the exploration of the root causes of infidelity would benefit from the theoretical combination of the evolutionary and investment approaches. One possible link between the two approaches revolves around the common manner in which they attempt to explain the motivation for infidelity. The specific motivational explanation provided in the investment model is that extradyadic partners may offer the individual a higher level of material and emotional benefits than his or her primary partner provides. Evolutionary theorists emphasize the importance of the same pragmatic benefits, but argue that the ultimate basis for what constitutes a benefit is whether it enhances the individuals RS. These two approaches are largely compatible with one another, and future research is likely to benefit from their cross-fertilization. Recommended Reading

Baker, R., & Bellis, M. (1995). (See References) Drigotas, S., Safstrom, C., & Gentilia, T. (1999). (See References) Humphrey, F. (1987). (See References) Laumann, E., Gagnon, J., Michael, R., & Michaels, S. (1994). (See References)

sity, Dallas, TX 75275; e-mail: sdrigota@mail.smu.edu.

References

Baker, R., & Bellis, M. (1995). Human sperm competition . London: Chapman & Hall. Buss, D. (1998). Evolutionary psychology . Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Buunk, B., & Bakker, A. (1995). Extradyadic sex: The role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Journal of Sex Research , 32, 313318. Daly, M., & Wilson, M. (1988). Homicide. Hawthorne, NJ: Aldine de Gruyter. Drigotas, S., Safstrom, C., & Gentilia, T. (1999). An investment model prediction of dating infidelJournal of Personality and Social Psychology , ity. 77, 509524. Glass, S., & Wright, T. (1977). The relationship of extramarital sex, length of marriage, and sex differences on marital satisfaction and romanJournal of Marriage and the Family 39, 691704. ticism: Athanasious data, reanalyzed. Glass, S., & Wright, T. (1985). Sex differences in type of extramarital involvement and marital Sex Roles , 12, 11011120. dissatisfaction. Humphrey, F. (1987). Treating extramarital sexual relationships in sex and couples therapy. In G. Integrating sex and mariWeeks & L. Hof (Eds.), tal therapy: A clinical guide (pp. 149170). New York: Brunner/Mazel. Kinsey, A., Pomeroy, W., Martin, C., & Gebhard, P. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female . Philadelphia: Saunders. Laumann, E., Gagnon, J., Michael, R., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality . Chicago: University of Chicago. Lusterman, D. (1997). Repetitive infidelity, womanizing, and Don Juanism. In R. Levant & G. Brooks Men and sex (pp. 8499). New York: Wiley. (Eds.), Rusbult, C.E., Drigotas, S.M., & Verette, J. (1994). The investment model: An interdependence analysis of commitment processes and relaCommunication tionship maintenance phenomena. In D. Ca-and relational maintenance (pp. 115139). San Diego: nary & L. Stafford (Eds.), Academic Press. Seal, D., Agostinelli, G., & Hannett, C. (1994). Extradyadic romantic involvement: Moderating Sex Roles , effects of sociosexuality and gender. 31, 122. Shackelford, T. (1998). Divorce as a consequence of spousal infidelity. In V. De Munck (Ed.), Romantic love and sexual behavior (pp. 135153). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Note

1. Address correspondence to Stephen Drigotas, Department of Psychology, Southern Methodist Univer-

Published by Blackwell Publishers Inc.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- E247Document3 paginiE247diego100% (1)

- How To Write Chapter 4Document33 paginiHow To Write Chapter 4LJLCNJKZSDÎncă nu există evaluări

- HubbleslawDocument11 paginiHubbleslawSajib IslamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistical Package For The Social Sciences (SPSSDocument8 paginiStatistical Package For The Social Sciences (SPSSAnonymous 0w6ZIvJODLÎncă nu există evaluări

- Facility Siting: Guideline and Process DevelopmentDocument45 paginiFacility Siting: Guideline and Process DevelopmentRuby SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment-7 Noc18 mg39 78Document4 paginiAssignment-7 Noc18 mg39 78Suman AgarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classification of Cynodon Spp. Grass Cultivars by UAVDocument5 paginiClassification of Cynodon Spp. Grass Cultivars by UAVIJAERS JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2009 Artificial Mouth Opening Fosters Anoxic ConditionsDocument7 pagini2009 Artificial Mouth Opening Fosters Anoxic ConditionsMartha LetchingerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quản trị học - C8Document11 paginiQuản trị học - C8Phuong PhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychology 2115B (Syllabus)Document7 paginiPsychology 2115B (Syllabus)Thomas HsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise 6B PG 154Document4 paginiExercise 6B PG 154Jocy BMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Albert Io StudyDocument142 paginiAlbert Io StudyMehmet Rüştü TürkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Manuscript of Group 1Document104 paginiFinal Manuscript of Group 1AYLEYA L. MAGDAONGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swati Tripathi: Jayoti Vidyapeeth Womens University, JaipurDocument18 paginiSwati Tripathi: Jayoti Vidyapeeth Womens University, JaipurdrsurendrakumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Easa 145 Safety PDFDocument53 paginiEasa 145 Safety PDFZain HasanÎncă nu există evaluări

- PR FINAL Research MethodDocument46 paginiPR FINAL Research MethodJv SeberiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Echo Hip Evaluation Final 1Document68 paginiEcho Hip Evaluation Final 1Fuad AlawzariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sampling Methods and Sample Size Calculation For The SMART MethodologyDocument34 paginiSampling Methods and Sample Size Calculation For The SMART MethodologyHazel BandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8875 - Y06 - Sy (Biology Higher 1)Document18 pagini8875 - Y06 - Sy (Biology Higher 1)Nurul AshikinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Educating School LeadersDocument89 paginiEducating School LeadersbujimaniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design BriefDocument2 paginiDesign Briefapi-409519942Încă nu există evaluări

- G6-research-In-progress.-.-. 1Document15 paginiG6-research-In-progress.-.-. 1Merielle Kate Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 Introduction To Thesis Writing SeminarDocument2 paginiChapter 1 Introduction To Thesis Writing SeminarJoveena VillanuevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design Engineering Applications of The Vexcel Ultracam Digital Aerial CameraDocument49 paginiDesign Engineering Applications of The Vexcel Ultracam Digital Aerial CameraNT SpatialÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applied Research Methods in Social Sciences SyllabusDocument25 paginiApplied Research Methods in Social Sciences SyllabusNicholas BransonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Process of HRPDocument22 paginiThe Process of HRPdpsahooÎncă nu există evaluări

- University Interview Questions 2020Document4 paginiUniversity Interview Questions 2020Santiago Romero Garzón100% (1)

- Course Syllabus in Lie Detection Techniques: Minane Concepcion, TarlacDocument8 paginiCourse Syllabus in Lie Detection Techniques: Minane Concepcion, TarlacJoy SherlynÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper Group 2 Out of School Youth-1Document10 paginiResearch Paper Group 2 Out of School Youth-1Sherryl Ann SalmorinÎncă nu există evaluări

- SFBT VSMS MisicDocument7 paginiSFBT VSMS MisicPrarthana SagarÎncă nu există evaluări