Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Caste System in India

Încărcat de

Sofía PiccolominoDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Caste System in India

Încărcat de

Sofía PiccolominoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA

The Indian caste system is the traditional organisation of South Asian, particularly Hindu, society into a hierarchy of hereditary groups called castes or jatis. In broad outline, marriage occurs only within caste (endogamy), caste is fixed by birth, and each caste is associated with a traditional occupation, such as weaving or barbering. Hindu religious principles underlay the caste hierarchy and limit the ways that castes can interact. The caste system is connected to the Hindu concept of the four varnas, which order and rank humanity by innate spiritual purity. The highest varna is the Brahmins, or priests. Next comes the Kshatriyas, the warriors, and then the Vaishyas, the merchants. The lowest varna is the Shudras, consisting of labourers, artisans and servants who do work that is ritually unclean. Contact between varnas, and particularly the sharing of food and water, must be limited to avoid pollution of higher, purer individuals by lower, more unclean ones. In practice, the caste system consists of thousands of jatis, generally of a local or regional nature. Each has its own history, customs, and claimed descent from one of the four varnas. Members of a jati may have many different professions, although commonly they will be related in status and nature to the jati's traditional occupation. Wealth and power generally rise with caste status, but individuals may be rich or poor. Subgroups within a jati may practice hypergamy or exogamy. There is no official or universal ranking that determines the caste hierarchy. Precedence depends on the local community's estimation of a jati's secular importance and ritual purity, and is therefore somewhat fluid. A jati can increase its status by growing in size, wealth and power, by avoiding low or unclean work, and by adopting priestly ways, such as vegetarianism and teetotalism, a process called sanskritisation. Generally, however, Brahmins are the highest caste, and at the bottom of society are those associated with occupations considered extremely unclean, such as handling garbage, excrement, or corpses. In the past these castes were called untouchables, because their touch polluted. They were often forbidden from entering temples, living inside the village, drinking from wells used by high castes, or even letting their shadows fall on a Brahmin. As India approached independence from British rule in the early 20th century, the caste system was increasingly criticised as a discriminatory and unjust system of social stratification, especially in regard to the impoverished untouchables. Two great figures of independence, B. R. Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi, led major reform movements, although they proposed radically different solutions. The current Indian constitution bans discrimination on the basis of caste and use of the term "untouchable", and the Indian government has instituted affirmative action programs for those who have become known as the Dalits, or "crushed peoples". Individual Dalits have achieved great political and financial success, but as a group they still complain of sometimes violent discrimination. The growth of information-age India has reduced the economic importance of the caste system, but its social and religious aspects remain a significant and sometimes divisive part of Indian life. HISTORY There are several theories regarding the origins of the Indian caste system. One posits that the Indian and Aryan classes show similarity, wherein the priests are Brahmins, the warriors are Kshatriya, the merchants are Vaishya, and the artisans are Shudras. Another theory is that of Georges Dumzil, who formulated thetrifunctional hypothesis of social class. According to the Dumzil theory, ancient societies had three main classes, each with distinct functions: the first judicial and priestly, the second connected with the military and war, and the third class focused on production, agriculture, craft and commerce. Dumzil proposed that Rex-Flamen of the Roman Empire is etymologically similar to Raj-Brahman of ancient India and that they made offerings to deus and deva respectively, each with statutes of conduct, dress and behavior that were similar. This theory became controversial, but drew support from many including Sophus Bugge in 1879. From the Bhakti school, the view is that the four divisions were originally created by Krishna. "According to the three modes of material nature and the work associated with them, the four divisions of human society were created."

Caste can be considered as an ancient fact of Hindu life, but various contemporary scholars have argued that the caste system as it exists today is the result of the British colonial regime, which made caste organisation a central mechanism of administration. According to scholars such as the anthropologist Nicholas Dirks, before colonialism caste affiliation was quite loose and fluent, but the British regime enforced caste affiliation rigorously, and constructed a much more strict hierarchy than existed previously, with some castes being criminalised and others being given preferential treatment. CASTE AND SOCIAL STATUS Doctrinally, caste was defined as a system of segregation of people, each with a traditional hereditary occupation. The Jtis were grouped by the Brahminical texts under the four well-known caste categories (the varnas): viz Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras. Certain people were excluded altogether, ostracised by all other castes and treated as untouchables. This ideological scheme was theoretically composed of 3000 sub-castes, which in turn was claimed to be composed of 90,000 local sub-groups, with people marrying only within their sub-group. This theory of caste was applied to what was then British India in the early 20th century, when the population comprised about 200 million people, across five major religions, and over 500,000 agrarian villages, each with a population between 100 to 1000 people of various age groups, variously divided into numerous rigid castes (British India included modern India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar). Castes - Rigid or Flexible? Ancient Indian texts suggest caste system was not rigid. This flexibility permitted lower caste Valmiki to compose the Ramayana, which was widely adopted and became a major Hindu scripture. Other ancient texts cite numerous examples of individuals moving from one caste to another within their lifetimes. Fa Xian, a Buddhist pilgrim from China, visited India around 400 AD. "Only the lot of theChandals he found unenviable; outcastes by reason of their degrading work as disposers of dead, they were universally shunned ... But no other section of the population were notably disadvantaged, no other caste distinctions attracted comment from the Chinese pilgrim, and no oppressive caste 'system' drew forth his surprised censure." In this period kings of Shudra and Brahmin origin were as common as those of Kshatriya Varna and caste system was not wholly rigid. Smelser and Lipset in their review of Hutton's study of caste system in colonial India propose the theory that individual mobility across caste lines may have been minimal in British India because it was ritualistic. They theorise that the subcastes may have changed their social status over the generations by fission, re-location, and adoption of new external ritual symbols. Some of these evolutionary changes in social stratifications, claim Smelser and Lipset, were seen in Europe, Japan, Africa and other regions as well; however, the difference between them may be the relative levels of ritualistic and secular referents. Smelser and Lipset further propose that the colonial system may have affected the caste system social stratification. They note that British colonial power controlled economic enterprises and the political administration of India by selectively cooperating with upper caste princes, priests and landlords. This was colonial India's highest level caste strata, followed by second strata that included favored officials who controlled trade, supplies to the colonial power and Indian administrative services. The bottom layer of colonial Indian society was tenant farmers, servants, wage labourers, indentured coolies and others. The colonial social strata acted in combination with the traditional caste system. The colonial strata shut off economic opportunity, entrepreneurial activity by natives, or availability of schools, thereby worsening the limitations placed on mobility by the traditional caste system. In America and Europe, they argue individual mobility was better than in India or other colonies around the world, because colonial stratification was missing and the system could evolve to become more secular and tolerant of individual mobility. Sociologists such as Srinivas and Damle have debated the question of rigidity in caste. In their independent studies, they claim considerable flexibility and mobility in their caste hierarchies. They assert that the caste system is far from rigid in which the position of each component caste is fixed for all time; instead, significant mobility across caste has been empirically observed in India.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Historia Del MOB - Sudeste AsiáticoDocument5 paginiHistoria Del MOB - Sudeste AsiáticoSofía PiccolominoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ceasar Bolanos Rejoin Der To FuchsDocument5 paginiCeasar Bolanos Rejoin Der To FuchsSrujanaBodapatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digital WorkDocument10 paginiDigital WorkSofía PiccolominoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Booklet Who Will Feed Us Without NotesDocument26 paginiBooklet Who Will Feed Us Without NotesSofía PiccolominoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Letter of Application2Document2 paginiLetter of Application2Sofía PiccolominoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- 50816notice 22-11-2021 For WebsiteDocument10 pagini50816notice 22-11-2021 For WebsiteAmitesh TejaswiÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument4 paginiNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentS84S100% (1)

- Mughal EditedDocument37 paginiMughal Editedgr82b_b2bÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perdana Smartfren 10GBDocument6 paginiPerdana Smartfren 10GBJhak PujaÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Introduction To Tithis and Their Effects On PersonalitiesDocument3 paginiAn Introduction To Tithis and Their Effects On PersonalitiesLeo JonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yoga Federation of India SyllabusDocument14 paginiYoga Federation of India SyllabusVishnuchaitanya Vich94% (17)

- AS9100 Certification StatusDocument192 paginiAS9100 Certification StatusMani Rathinam RajamaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adam SandlerDocument50 paginiAdam Sandlerindians jonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Untitled 5 PDFDocument6 paginiUntitled 5 PDFDeepak saxenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comprehensive Specialities With The Finest Consultants: Paediatric SurgeryDocument2 paginiComprehensive Specialities With The Finest Consultants: Paediatric SurgeryKapil PatwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Polytechnic CollegesDocument10 paginiList of Polytechnic CollegesPrathap_donÎncă nu există evaluări

- Common Errors in English Grammar: Here Is A List If Common Errors That Are Most Commonly Asked in CompetitiveDocument53 paginiCommon Errors in English Grammar: Here Is A List If Common Errors That Are Most Commonly Asked in CompetitivechaostheoristÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cha KaraDocument72 paginiCha KaraBidesh BiswasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ramastubhagwanswayam 2Document211 paginiRamastubhagwanswayam 2Rambhakt Niroj PrasadÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4.2 The Role of Mātikā in The Abhidhamma Mātikā Is Tabulated and Classified in A Systematization of Doctrines inDocument2 pagini4.2 The Role of Mātikā in The Abhidhamma Mātikā Is Tabulated and Classified in A Systematization of Doctrines inLong Shi100% (2)

- Yajurveda Upakarma 2019 MantrasDocument18 paginiYajurveda Upakarma 2019 MantrasSubramoni RajuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eves May EversionDocument84 paginiEves May EversionSwati AmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cross Sectional Study To Find Out The Prevalence of Tobacco Use Among High School & Higher Secondary Class Students of Government Schools of BhopalDocument9 paginiCross Sectional Study To Find Out The Prevalence of Tobacco Use Among High School & Higher Secondary Class Students of Government Schools of BhopalAdvanced Research PublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Reformers of KeralaDocument11 paginiSocial Reformers of KeralasainudheenkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Institution Building by UdaipareekDocument479 paginiInstitution Building by UdaipareekramanathanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women of Ancient IndiaDocument58 paginiWomen of Ancient IndiaLeonardo da CapriÎncă nu există evaluări

- JawaDocument29 paginiJawasudhak111Încă nu există evaluări

- Nov-Dec 2011 Issue of JASADocument0 paginiNov-Dec 2011 Issue of JASAProfessorAsim Kumar MishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Members Details: Name of Applicant M. No. App. No. Contact No Email ID AddressDocument6 paginiMembers Details: Name of Applicant M. No. App. No. Contact No Email ID Addressraghu112211Încă nu există evaluări

- Sohit Mishra - Real History of Nehru Family Must Read-With Facts..Document1 paginăSohit Mishra - Real History of Nehru Family Must Read-With Facts..sirsa11Încă nu există evaluări

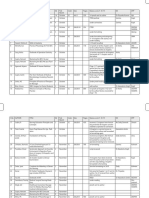

- Results Clerical 2013Document36 paginiResults Clerical 2013nandipabitra10Încă nu există evaluări

- UttaraKanda SriRamCharitaManasaDocument153 paginiUttaraKanda SriRamCharitaManasaPrashant VashiÎncă nu există evaluări

- WiccaDocument15 paginiWiccakai stevenson100% (3)

- Examination Centre ListDocument54 paginiExamination Centre Listrkthbd58450% (3)

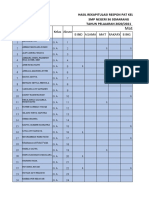

- Rekap Pat Kelas 9Document22 paginiRekap Pat Kelas 9smp36smgÎncă nu există evaluări