Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Henri Lefebvre

Încărcat de

burnnotetestDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Henri Lefebvre

Încărcat de

burnnotetestDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Henri Lefebvre (16 June 1901 29 June 1991) was a French Marxist philosopher and sociologist, b est known

for pioneering the critique of everyday life, for introducing the conc epts of the right to the city and the production of social space, and for his wo rk on dialectics, alienation, and criticism of Stalinism and structuralism. In h is prolific career, Lefebvre wrote more than sixty books and three hundred artic les.[1] Contents 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Biography The critique of everyday life The social production of space Bibliography Books on Lefebvre References External links

Biography Lefebvre was born in Hagetmau, Landes, France. He studied philosophy at the Univ ersity of Paris (the Sorbonne), graduating in 1920. By 1924 he was working with Paul Nizan, Norbert Guterman, Georges Friedmann, Georges Politzer and Pierre Mor hange in the Philosophies group seeking a "philosophical revolution".[2] This br ought them into contact with the Surrealists, Dadaists, and other groups, before they moved towards the French Communist Party (PCF). Lefebvre joined the PCF in 1928 and became one of the most prominent French Marx ist Intellectuals during the second quarter of the 20th century, before joining the French resistance.[3] From 1944 to 1949, he was the director of Radiodiffusi on Fran?aise, a French radio broadcaster in Toulouse. Among his works was a high ly influential, anti-Stalinist, text on dialectics called Dialectical Materialis m (1940). Seven years later, Lefebvre published his first volume of The Critique of Everyday Life, which would later serve as a primary intellectual inspiration for the founding of COBRA and, eventually, of the Situationist International.[4 ] His early work on method was applauded and borrowed centrally by Sartre in The Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960). During Lefebvre s thirty year stint with t he PCF, he was chosen to publish critical attacks on opposed theorists, especial ly existentialists like Sartre and Lefebvre's former colleague Nizan,[5] only to intentionally get himself expelled from the party for his own heterodox theoret ical and political opinions in the late 1950s. Ironically, he became one of Fran ce s most important critics of the PCF s politics (e.g. immediately, the lack of an opinion on Algeria, and more generally, the partial apologism for and continuati on of Stalinism) and intellectual thought (i.e. Structuralism, especially the wo rk of Louis Althusser).[6] In 1961, Lefebvre became professor of sociology at the University of Strasbourg, before joining the faculty at the new university at Nanterre in 1965.[7] He was one of the most respected professors, and he had influenced and analysed the Ma y 1968 students revolt.[8] Lefebvre introduced the concept of the right to the c ity in his 1968 book Le Droit ? la ville[9][10] (the publication of the book pre dates the May 1968 revolts which took place in many French cities). Following th e publication of this book, Lefebvre wrote several influential works on cities, urbanism, and space, including The Production of Space (1974), which became one of the most influential and heavily cited works of urban theory. By the 1970s, L efebvre had also published some of the first critical statements on the work of post-structuralists, especially Foucault.[11] During the following years he was involved in the editorial group of Arguments, a New Left magazine which largely served to enable the French public to familiarize themselves with Central Europe an revisionism.[12]

Lefebvre died in 1991. In his obituary, Radical Philosophy magazine honored his long and complex career and influence: "the most prolific of French Marxist intellectuals, died during the night of 28 29 June 1991, less than a fortnight after his ninetieth birthday. During his l ong career, his work has gone in and out of fashion several times, and has influ enced the development not only of philosophy but also of sociology, geography, p olitical science and literary criticism."[13] The critique of everyday life One of Lefebvre's most important contributions to social thought is the idea of the "critique of everyday life," which he pioneered in the 1930s. This work was influential in French theory, particularly for the Situationists, as well as in politics (e.g. for the May 1968 student revolts).[14] While the theme presented itself in many works, it was most notably outlined in his eponymous 3 volume stu dy, which came out in individual installments, decades apart, in 1947, 1961, and 1981. Lefebvre defined everyday life dialectically as the intersection of illusion and truth, power and helplessness; the intersection of the sector man controls and t he sector he does not control ,[15] and is where the perpetually transformative co nflict occurs between diverse, specific rhythms: the body s polyrhythmic bundles o f natural rhythms, physiological (natural) rhythms, and social rhythms (Lefebvre and R?gulier, 1985: 73.[16] The idea was that through autocritique, people coul d understand and then revolutionize their everyday lives. This was essential to Lefebvre because everyday life was where he saw capitalism surviving and reprodu cing itself. Without revolutionizing everyday life, capitalism would continue to diminish the quality of everyday life, and inhibit real self expression. The social production of space Lefebvre dedicated a great deal of his philosophical writings to understanding t he importance of (the production of) space in what he called the reproduction of social relations of production. This idea is the central argument in the book T he Survival of Capitalism, written as a sort of prelude to La Production de l espa ce (1974) (The Production of Space). These works have deeply influenced current urban theory, mainly within human geography, as seen in the current work of auth ors such as David Harvey, Dolores Hayden, and Edward Soja, and in the contempora ry discussions around the notion of Spatial justice. Lefebvre is widely recogniz ed as a Marxist thinker who was responsible for widening considerably the scope of Marxist theory, embracing everyday life and the contemporary meanings and imp lications of the ever expanding reach of the urban in the western world througho ut the 20th century. The generalization of industry, and its relation to cities (which is treated in La Pens?e marxiste et la ville), The Right to the City and The Urban Revolution were all themes of Lefebvre's writings in the late 1960s, w hich was concerned, among other aspects, with the deep transformation of "the ci ty" into "the urban" which culminated in its omni-presence (the "complete urbani zation of society"). In his book The Urban Question, Manuel Castells criticizes Lefebvre's Marxist Hu manism and approach to the city influenced by Hegel and Nietzsche. Castells' pol itical criticisms of Lefebvre's approach to Marxism echoed the Structuralist Sci entific Marxism school of Louis Althusser of which Lefebvre was an immediate cri tic. Many responses to Castells are provided in The Survival of Capitalism, and some may argue[who?] that the acceptance of those critiques in the academic worl d would be a motive for Lefebvre's effort in writing the long and theoretically dense The Production of Space. Lefebvre contends that there are different modes of production of space (i.e. sp

atialization) from natural space ('absolute space') to more complex spatialities whose significance is socially produced (i.e. social space).[17] Lefebvre analy ses each historical mode as a three-part dialectic between everyday practices an d perceptions (le per?u), representations or theories of space (le con?u) and th e spatial imaginary of the time (le v?cu).[18] His conception of "imaginary" dra ws from the work Cornelius Castoriadis. Lefebvre's argument in The Production of Space is that space is a social product , or a complex social construction (based on values, and the social production o f meanings) which affects spatial practices and perceptions. This argument impli es the shift of the research perspective from space to processes of its producti on; the embrace of the multiplicity of spaces that are socially produced and mad e productive in social practices; and the focus on the contradictory, conflictua l, and, ultimately, political character of the processes of production of space. [19] As a Marxist theorist (but highly critical of the economic structuralism th at dominated the academic discourse in his period), Lefebvre argues that this so cial production of urban space is fundamental to the reproduction of society, he nce of capitalism itself. The social production of space is commanded by a hegem onic class as a tool to reproduce its dominance (see Gramsci). "(Social) space is a (social) product [...] the space thus produced also ser ves as a tool of thought and of action [...] in addition to being a means of pro duction it is also a means of control, and hence of domination, of power."[20] Lefebvre argued that every society - and therefore every mode of production - pr oduces a certain space, its own space. The city of the ancient world cannot be u nderstood as a simple agglomeration of people and things in space - it had its o wn spatial practice, making its own space (which was suitable for itself - Lefeb vre argues that the intellectual climate of the city in the ancient world was ve ry much related to the social production of its spatiality). Then if every socie ty produces its own space, any "social existence" aspiring to be or declaring it self to be real, but not producing its own space, would be a strange entity, a v ery peculiar abstraction incapable of escaping the ideological or even cultural spheres. Based on this argument, Lefebvre criticized Soviet urban planners, on t he basis that they failed to produce a socialist space, having just reproduced t he modernist model of urban design (interventions on physical space, which were insufficient to grasp social space) and applied it onto that context: "Change life! Change Society! These ideas lose completely their meaning with out producing an appropriate space. A lesson to be learned from soviet construct ivists from the 1920s and 30s, and of their failure, is that new social relation s demand a new space, and vice-versa."[21] Bibliography 1925 Positions d'attaque et de d?fense du nouveau mysticisme, Philosophies 5 -6 (March). pp. 471 506. (Philosophy. Pt. 2 of the "Philosophy of Consciousness" p roject on being, consciousness and identity originally proposed as a thesis topi c to L?on Brunschvicg). 1934 with Norbert Guterman, Morceaux choisis de Karl Marx, Paris: NRF. (nume rous reprintings). 1936 with Norbert Guterman, La Conscience mystifi?e, Paris: Gallimard (new e d. Paris: Le Sycomore, 1979). 1937 Le nationalisme contre les nations (Preface by Paul Nizan), Paris: Edit ions sociales internationales (reprinted, Paris: M?ridiens-Klincksliek, 1988, Co llection "Analyse institutionnelle", Pr?sentation M. Trebitsch, Postface Henri L efebvre). 1938 Hitler au pouvoir, bilan de cinq ann?es de fascisme en Allemagne, Paris : Bureau d'Editions. 1938 with Norbert Guterman, Morceaux choisis de Hegel, Paris: Gallimard (3 r

eprintings 1938-*1939, reprinted Collection "Id?es", 2 vols. 1969). 1938 with Norbert Guterman, Cahiers de L?nine sur la dialectique de Hegel , Paris: Gallimard. 1939 Nietzsche, Paris: Editions sociales internationales. 1946 L'Existentialisme, Paris: Editions du Sagittaire. 1947 Logique formelle, logique dialectique, Vol. 1 of A la lumi?re du mat?ri alisme dialectique, written in 1940-41 (2nd volume censored). Paris: Editions so ciales. 1947 Descartes, Paris: Editions Hier et Aujourd'hui. 1947 Critique de la vie quotidienne, L'Arche 1942 Le Don Juan du Nord, Europe revue mensuelle 28, April 1948, pp. 73 104. 1950 Knowledge and Social Criticism, Philosophic Thought in France and the U SA Albany N.Y.: State University of New York Press. pp. 281 300 (2nd ed. 1968). 1958 Probl?mes actuels du marxisme, Paris: Presses universitaires de France; 4th edition, 1970, Collection "Initiation philosophique" 1958 (with Lucien Goldmann, Claude Roy, Tristan Tzara) Le romantisme r?volut ionnaire, Paris: La Nef. 1961 Critique de la vie quotidienne II, Fondements d'une sociologie de la qu otidiennet?, Paris: L'Arche. 1963 La vall?e de Campan - Etude de sociologie rurale, Paris: Presses Univer sitaires de France. 1965 M?taphilosophie, foreword by Jean Wahl, Paris: Editions de Minuit, Coll ection "Arguments". 1965 La Proclamation de la Commune, Paris: Gallimard, Collection "Trente Jou rn?es qui ont fait la France". 1968 Le Droit ? la ville, Paris: Anthropos (2nd ed.); Paris: Ed. du Seuil, C ollection "Points". 1968 La vie quotidienne dans le monde moderne, Paris: Gallimard, Collection "Id?es". 1968 Dialectical Materialism, Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesot a Press, 1968. Reprinted 2009, ISBN 978-0-8166-5618-9, retrieved 26 September 20 10 First published 1940 by Presses Universitaires de France, as Le Mat?rialisme Dialectique. First English translation published 1968 by Jonathan Cape Ltd. ISB N 0-224-61507-6 1968 Sociology of Marx, N. Guterman trans. of 1966c, New York: Pantheon. 1969 The Explosion: From Nanterre to the Summit, Paris: Monthly Review Press . Originally published 1968. 1970 La r?volution urbaine Paris: Gallimard, Collection "Id?es". 1971 Le manifeste diff?rentialiste, Paris: Gallimard, Collection "Id?es". 1971 Au-del? du structuralisme, Paris: Anthropos. 1972 La pens?e marxiste et la ville, Tournai and Paris: Casterman. 1973 La survie du capitalisme; la re-production des rapports de production. Trans. Frank Bryant as The Survival of Capitalism. London: Allison and Busby, 19 76. 1974 La production de l'espace, Paris: Anthropos. Translation and Pr?cis (av ailable online). 1974 with Leszek Ko?akowski Evolution or Revolution, F. Elders, ed. Reflexiv e Water: The Basic Concerns of Mankind, London: Souvenir. pp. 199 267. ISBN 0-28564742-3 1975 Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, ou le royaume des ombres, Paris: Tournai, Caste rman. Collection "Synth?ses contemporaines". ISBN 2-203-23109-2 1975 Le temps des m?prises: Entretiens avec Claude Glayman, Paris: Stock. IS BN 2-234-00174-9 1978 with Catherine R?gulier La r?volution n'est plus ce qu'elle ?tait, Pari s: Editions Libres-Hallier (German trans. Munich, 1979). ISBN 2-264-00849-0 1978 Les contradictions de l'Etat moderne, La dialectique de l'Etat, Vol. 4 of 4 De 1'Etat, Paris: UGE, Collection "10/18". 1980 La pr?sence et l'absence, Paris: Casterman. ISBN 2-203-23172-6 1981 Critique de la vie quotidienne, III. De la modernit? au modernisme (Pou r une m?taphilosophie du quotidien) Paris: L'Arche.

1981 De la modernit? au modernisme: pour une m?taphilosophie du quotidien, P aris: L'Arche Collection "Le sens de la march?". 1985 with Catherine R?gulier-Lefebvre, Le projet rythmanalytique Communicati ons 41. pp. 191 199. 1986 with Serge Renaudie and Pierre Guilbaud, "International Competition for the New Belgrade Urban Structure Improvement", in Autogestion, or Henri Lefebvr e in New Belgrade, Vancouver: Fillip Editions. ISBN 978-0-9738133-5-7 1988 Toward a Leftist Cultural Politics: Remarks Occasioned by the Centenary of Marx's Death, D. Reifman trans., L.Grossberg and C.Nelson (eds.) Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, Urbana: University of Illinois Press; New York: Macmillan. pp. 75 88. ISBN 0-252-01108-2 1991 The Critique of Everyday Life, Volume 1, John Moore trans., London: Ver so. Originally published 1947. ISBN 0-86091-340-6 1991 with Patricia Latour and Francis Combes, Conversation avec Henri Lefebv re P. Latour and F. Combes, eds. Paris: Messidor, Collection "Libres propos". 1991 The Production of Space, Donald Nicholson-Smith trans., Oxford: Basil B lackwell. Originally published 1974. ISBN 0-631-14048-4 1992 with Catherine Regulier-Lefebvre ?l?ments de rythmanalyse: Introduction ? la connaissance des rythmes, preface by Ren? Lorau, Paris: Ed. Syllepse, Coll ection "Explorations et d?couvertes". English translation: Rhythmanalysis: Space , time and everyday life, Stuart Elden, Gerald Moore trans. Continuum, New York, 2004. 1995 Introduction to Modernity: Twelve Preludes September 1959-May 1961, J. Moore, trans., London: Verso. Originally published 1962. ISBN 1-85984-961-X 1996 Writings on Cities, E. Kofman and E. Lebas, trans. and eds., Oxford: Ba sil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19187-9 2003 Key Writings, Stuart Elden, Elizabeth Lebas, Eleonore Kofman, eds. Lond on/New York: Continuum. 2009 State, Space, World: Selected Essay, Neil Brenner, Stuart Elden, eds. G erald Moore, Neil Brenner, Stuart Elden trans. Minneapolis: University of Minnes ota Press. Books on Lefebvre Rob Shields, Love and Struggle - Spatial Dialectics (London: Routledge 1999) Stuart Elden, Understanding Henri Lefebvre: Theory and the Possible (London/ New York: Continuum, 2004) Andy Merrifield, Henri Lefebvre: A Critical Introduction (London: Routledge, 2006) Goonewardena, K., Kipfer, S., Milgrom, R. & Schmid, C. eds. Space, Differenc e, Everyday Life: Reading Henri Lefebvre. (New York: Routledge, 2008) Stanek, L. Henri Lefebvre on Space: Architecture, Urban Research, and the Pr oduction of Theory. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011) Andrzej Zieleniec: Space and Social Theory, London 2007, p. 60 97.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- For A Historical Application.: Ban (Information)Document1 paginăFor A Historical Application.: Ban (Information)burnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural RelativismDocument1 paginăCultural RelativismburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Max WeberDocument1 paginăMax WeberburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robin HortonDocument3 paginiRobin HortonburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Origination of Cognitive BiasesDocument1 paginăOrigination of Cognitive BiasesburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alan DundesDocument3 paginiAlan DundesburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive Bias OverviewDocument1 paginăCognitive Bias OverviewburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rich Text Editor FileDocument1 paginăRich Text Editor FileburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- EthnocentrismDocument1 paginăEthnocentrismburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dan SperberDocument3 paginiDan SperberburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stuart KauffmanDocument3 paginiStuart KauffmanburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macrocosm and MicrocosmDocument1 paginăMacrocosm and MicrocosmburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caroline HumphreyDocument2 paginiCaroline HumphreyburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stuart KauffmanDocument3 paginiStuart KauffmanburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Sacrifice RegionalDocument1 paginăHuman Sacrifice RegionalburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Animal SacrificeDocument1 paginăAnimal SacrificeburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rich Text Editor FileDocument1 paginăRich Text Editor FileburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethnocentrism AnthropologyDocument1 paginăEthnocentrism AnthropologyburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sacrifice OverviewDocument1 paginăSacrifice OverviewburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anti Nationalism SocialistDocument1 paginăAnti Nationalism SocialistburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethnocentrism Origins of The Concept and Its StudyDocument1 paginăEthnocentrism Origins of The Concept and Its StudyburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- EthnocentrismDocument1 paginăEthnocentrismburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anti Nationalism Liberal and PacifistDocument1 paginăAnti Nationalism Liberal and PacifistburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- National PurityDocument1 paginăNational PurityburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- National PurityDocument1 paginăNational PurityburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anti NationalismDocument1 paginăAnti NationalismburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anti Colonial NationalismDocument1 paginăAnti Colonial NationalismburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- UltranationalismDocument1 paginăUltranationalismburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- National PurityDocument1 paginăNational PurityburnnotetestÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Week 1 - Intrduction To Nursing Research - StudentDocument24 paginiWeek 1 - Intrduction To Nursing Research - StudentWani GhootenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Standard: Methods of Test For Aggregates For ConcreteDocument22 paginiIndian Standard: Methods of Test For Aggregates For ConcreteAnuradhaPatraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Universiti Teknologi Mara (Uitm) Shah Alam, MalaysiaDocument4 paginiUniversiti Teknologi Mara (Uitm) Shah Alam, MalaysiaSuraya AdriyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Close Up b1 AnswersDocument6 paginiClose Up b1 Answersmega dragos100% (1)

- Tecnicas Monitoreo CorrosionDocument8 paginiTecnicas Monitoreo CorrosionJavier GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alonex Special Amp Industrial Electronic Equipment PDFDocument342 paginiAlonex Special Amp Industrial Electronic Equipment PDFthanh vanÎncă nu există evaluări

- DSO Digital Storage Oscilloscope: ApplicationDocument2 paginiDSO Digital Storage Oscilloscope: ApplicationmsequipmentsÎncă nu există evaluări

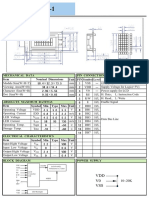

- V0 VSS VDD: Unit PIN Symbol Level Nominal Dimensions Pin Connections Function Mechanical Data ItemDocument1 paginăV0 VSS VDD: Unit PIN Symbol Level Nominal Dimensions Pin Connections Function Mechanical Data ItemBasir Ahmad NooriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lac CultureDocument7 paginiLac CultureDhruboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arts NPSH TutorialDocument3 paginiArts NPSH TutorialDidier SanonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Java ProgrammingDocument134 paginiJava ProgrammingArt LookÎncă nu există evaluări

- Service Manual: DDX24BT, DDX340BTDocument94 paginiService Manual: DDX24BT, DDX340BTDumur SaileshÎncă nu există evaluări

- ABC Press Release and AllocationDocument28 paginiABC Press Release and AllocationAndrew Finn KlauberÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thi Thu TNTHPT - Tieng Anh 12 - 136Document5 paginiThi Thu TNTHPT - Tieng Anh 12 - 136Yến LinhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructional Module: IM No.: IM-NSTP 1-1STSEM-2021-2022Document6 paginiInstructional Module: IM No.: IM-NSTP 1-1STSEM-2021-2022Princess DumlaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vichinsky Et Al.2019Document11 paginiVichinsky Et Al.2019Kuliah Semester 4Încă nu există evaluări

- MUMBAI ConsultantsDocument43 paginiMUMBAI ConsultantsER RaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technical Seminar Report CV94Document62 paginiTechnical Seminar Report CV941MS19CV053 KARTHIK B SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preparation of Giemsa Working SolutionDocument4 paginiPreparation of Giemsa Working SolutionMUHAMMAD DIMAS YUSUF 1903031Încă nu există evaluări

- Abu Khader Group ProposalDocument5 paginiAbu Khader Group ProposalChristine AghabiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Simulation and Analysis of 10 Gbps APD Receiver With Dispersion CompensationDocument5 paginiSimulation and Analysis of 10 Gbps APD Receiver With Dispersion CompensationMohd NafishÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of Employees' Commitment Towards Food Safety at Ayana Resort, BaliDocument58 paginiThe Impact of Employees' Commitment Towards Food Safety at Ayana Resort, Balirachelle agathaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sika Decap PDFDocument2 paginiSika Decap PDFthe pilotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prudence and FrugalityDocument17 paginiPrudence and FrugalitySolaiman III SaripÎncă nu există evaluări

- MLA 7th Edition Formatting and Style GuideDocument14 paginiMLA 7th Edition Formatting and Style Guideapi-301781586Încă nu există evaluări

- B1+ Exam MappingDocument3 paginiB1+ Exam Mappingmonika krajewskaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture & CivilizationDocument21 paginiCulture & CivilizationMadhuree Perumalla100% (1)

- Ee - Lab ReportDocument36 paginiEe - Lab ReportNoshaba Noreen75% (4)

- Arguments and FallaciesDocument18 paginiArguments and FallaciesSarah Mae Peñaflor Baldon-IlaganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daily ReportDocument39 paginiDaily ReportLe TuanÎncă nu există evaluări