Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Dementia Care 3 End of Life Care

Încărcat de

dogstar23Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Dementia Care 3 End of Life Care

Încărcat de

dogstar23Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Dementia care.

Part 3: end-of-life care

for people with advanced dementia

Emma Ouldred, Catherine Bryant

diagnosis of dementia (Kay et al, 2000). Additionally, tbere is

no cure for most tbrms of dementia; it is a progressive disease,

Abstract a terminal condition like cancer, and yet it is not recognized

End-of-life care issues for people with advanced dementia have only as such. Access to palliative care services for people with

recentíy been addressed in guidance. There appear to be barriers to advanced dementia is unequal and mucb less defined than

accessing good palliative care for people in the terminal phase of the palliative care tor other terminal diseases such as cancer.

disease. The reasons for this are multifactorial, but may be attributed

to factors such as dementia not being recognized as a terminal What is palliative care?

disease like cancer, problems in recognizing the symptoms of terminal Tbe World Healtb Organization (WHO. 2004) recently

dementia, and decision-making conflicts between family caregivers and stated tbat 'every person witb a progressive illness bas a right

other health and social care providers. This article highlights common to palliative care', and tbat palliative care is 'tbe active total

symptoms of advanced dementia, and the need for a palliative care care of patients and families by a multiprofessional team

approach. It also addresses specific issues in both caring for people wben the patients disease is no longer responsive to curative

with dementia at the end of their lives and in supporting carers. treatment" (WHO, 1990).

Tbe wider model of palliative care fits well witb tbe

Key words: Advanced dementia • Carer support • Palliative care person-centred approach to dementia care first proposed

by Kitwood (1997), wbicb promotes bolistic care and a

need to see tbe person ratber than tbe disease. AccortÜng to

P

art 1 of this series outlined recent guidance on Henderson (2007), palliative care:

demenria care and provided information on dementia • Provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

and its different subtypes, the assessment process • Affirms life and sees dying as a natural process

and the utility of cognitive screening tools. Part 2 • Intends neither to hasten nor postpone death

focused on cienieiitiLi management, with particular emphasis on • Integrates tbe psychological and spiritual aspects of patient

understanding and managing behavioural challenges; it described care

psychosocial interventions in dementia care in addition to • Offers a support system to belp people live as actively as

discussing current drug treatments for the condition. possible until deatb, and to families to belp cope during

This article, part 3, brietly detines palliative care and explores illness and bereavement.

issues around barriers to palliative care in advanced dementia. However, the palliative care approach to dementia does

It provides guidance on recognizing the advanced stages of not appear to be commonly adopted throughout tbe UK.

dementia, and bow nurses can care for and support people In 2002, tbe Audit Commission reported that specialist

with dementia in tbe tinal stages of their disease. Significantly, support for managing people with advanced dementia was

it also makes reference to tbe difficult decisions tacing family not available in 40% of all areas of the UK, and dementia

caregivers at this stage and the psychological impact of care specialists lack confidence in providing palliative care.

advanced dementia on caregivers. Sampson et al (2006) undertook a retrospective case-note

audit of older patients dying on an acute medical ward in

Background 2002-2003; those with dementia were much less likely to

Approximately 10000 people with dementia die eacb year in be referred to palliative care services than those without

tbe United Kingdom (UK) (Harris, 2007). Of tbi.s number, a diagnosis of dementia (9% I'i 25%), and were prescribed

over 40% die in tbe community (McCartby et al, 1997; Kay et fewer palliative medications (28% i>s 51%). A retrospective

al, 2000), and over 50% in hospital (McCarthy et al, 1997). Less study on a hospital ward for older people with mental

tban 2% of people in hospice care in tbe UK have a primary bealtb needs in the UK showed patients witb end-stage

dementia bad a number of symptoms for which they did

not receive adequate palliative care (Lloyd-WilHams and

Emma Ouldred is Deriicnti.i Niirst? Specialist and Catherine Bryant is Payne, 2002).

Consultant Physiciiin, King's College Hospitai NHS Trust, London

Guidance on end-of-llfe care for older people

Acct'picd tor pitblicalum:Jatmary 2008

Recently, attention has been tbcused on improving end-

of-life care for all older people. The Department of

308 |oiini.il of Nursing. 2UiIS,Viil 17. No 5

NEUROSCIENCE NURSING

I leakh (DH, 2004) document, The NHS Improvement Plan. care teams should assess the palliative needs of people close

included a commitment to develop a training programme to death and relay information to other members of health

lor staff working in primary care homes and hospitals to and social care. Specific guidance relating to nutrition, pain

ensure all people at the end of life, regardless of diagnosis, relief and resuscitation is also included.

should have the choice of deciding where to die and how NICE (2006) also recommends that practitioners discuss

they wish to be treated. In the Government white paper, certain issues with the person with dementia while he or

i)iir Health Our Care Our Say (DH, 20i)6a), a commitment she still has capacity, and to ensure people are familiar with

was expressed to extend palliative care to .ill who need it the main clauses of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA),

regardless of terminal condition. which is initiated when a person does not have capacity.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Such areas of discussion include:

(NICE, 2004) has produced guidance on improving support • Use of advance statements (stating what is to be done if a

and palliative care for adults with cancer, and although this person loses capacity to communicate or make decisions)

work is focused on services for adult patients with cancer • Advance decisions to refuse treatment

•liid their families, it may inform the development of service • Lasting power of attorney

models for other groups of patients. The NICE (2004) • A preferred place-of-care plan.

document recommends three tools to support high-quality

end-of-life care: Barriers to providing palliative care

• The Gold Standards Framework (Thomas. 2003) There are several barriers to overcome in order to achieve

• t'he Liverpool care pathway Care of the Oyin^iA Pathway excellent end-of-hfe care for people with dementia, namely:

to Excellence (EUershaw and Wilkinson, 2(K)3) • Dementia is not recognized as terminal disease

• The "Preferred Place of Care Plati" (www. cancerlan cash ire. • There are difficulties in prognostication and difficulties in

ürg.uk/ppc.html). recognizing when somebody reaches the point at which

The NHS End of Ufe Care Programme (DH, 2005) aims to care becomes palliative

improve care at the end of life for all. and the programuîc • Problems in client communicability that impacts on

website (www.endotlifecare.nhs.uk/eoic) provides good symptom management

practice, information and resources, including links to the • A lack of skills and knowledge in providers of care regarding

three tools. palliative care for people with advanced dementia, and

a lack of access to specialist palliative care consultation

Guidance on end-of-llfe care (Shuster, 200(i)

The development of policies specifically related to end-of- • A lack of education and support about complications

life care for people with dementia has evolved slowly, but of advanced dementia, and limits to treatment options

recently a number of important documents have addressed encourages healthcare proxies to request admission to

this complex issue. Recent guidance has stipulated that hospital and aggressive interventions (Koopnians et al,

older people with mental health problems should have 2003)

equal access to the same home-based end-of-care services • A lack of advance decisions that set out the wishes of a

as others, and that a palliative care model of service person to ta-atment in advance.There is evidence to suggest

delivery should be made available for people with dementia that a person with dementia is significantly less likely than

supported with advice from general medicine physicians a person with cancer to have set up advance decisions

,uid palhative care services (Care Services Improvement (Mitchell et .i!, 2004).

Partnership, 2005).

Programmes on dignity and end of life, and mental health Advanced dementia

in old age, are included in the follow-up to the document it is not inevitable that all people with dementia will reach

A New Ambition for Old A^e: Next Steps in Impleiiiv!iliii_i; the the end stages of their disease before death. Cox and Cook

National Service Framework for Older People (DH, 2006b). (2002) describe three ways in which people with dementia

Dementia and palliative care are also included in the die, namely:

Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) for the GP • People with dementia may die with a medical condition

contract. Under this framework, GPs must hold a register of that is unrelated to the dementia, e.g. people with tnild

patients diagnosed with dementia, and under the paUiative dementia who develop and subsequently die from cancer

care QOF GPs must hold regular review meetings of these • People with dementia may die from a complex mix of

patients (Royal College of General Practitioners, 2006). mental health and physical problems where dementia is

NICE issued guidance on dementia in 2006. which not the primary cause of death but interacts with other

specifically addressed the need for a palliative care approach conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

to dementia care to be adopted from diagnosis to death • People with dementia may die with comphcations arising

to enhance the quality of life of people with dementia advanced dementia.

and to enable them to die with dignity in an appropriate

environment. A holistic approach to care is recommended, Signs and symptoms

which encompasses the physical, psychological, social and When does a person stop living with dementia and start

spiritual needs of people with dementia, and also emphasizes dying from it? Failure to recognize when a person has

the importance of supporting families and carers. Primary entered the advanced stages of dementia has been proposed

UritishJuuriMl ol'Nursing,2tKm.Vol 17.No 5 309

the presence of severe cognitive impairment, conimunication

Box 1. Typical features of advanced difficulties or language and cultural barriers.

The analgesic drug of choice is influenced by the severity of

dementia

pain. However, it is usual to gradually move up the analgesic

ladder and start with a simple drug such as paracetamol. Some

Dependence in activities of daily living requiring the people with dementia will require morphine, but this is likely

assistance of caregivers to survive to increa.se confusion (National Council for Palliative Care

Severe impairment of expressive and receptive and Alzheimer's Society, 2006). Codeine is commonly used,

communication often limited to single words or nonsense but again it can sometimes cause increased confusion and is

phrases likely to cause constipation (British National Formulai^ 2008).

Loss of the ability to walk followed by inability to stand. Analgesics should be administered regularly every 3—6 hours

problems maintaining sitting posture and a subsequent loss rather, than on demand, to ensure freedom from pain (WHO,

of head and neck control 2006).Transdermal patches and medication, which are available

Deveiopment of contractures because of muscle rigidity and

in suspension or dispenible format, should be considered. Non-

de-conditioning

pharmacological ways of managing pain, such as aromatherapy,

Loss of ability to recognize food, self-feed and swallow

massage and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, should

effectively

be considered despite a lack of evidence.

Bowel and bladder incontinence

[nabiiity to recognize seifand others

SAvaUo\ving, eatíng and drinking

Dysphagia is a common feature of advanced dementia,

as a possible barrier to the provision of palliative care for affecting up to 70% of people (Feinberg et al, 1992). Other

this vulnerable group. Box 1 outlines typical features of factors affecting nutrition in advanced dementia include loss

advanced dementia and may help practitioners understand of appetite, loss of hunger and problems with dyspraxia that

when palliative care services should be initiated. affect the process of feeding (Hughes et al, 2007).

Specific care issues Management

Cominunication Eating apraxia can be managed by hand-feeding, and fooil

Problems wich communication are common in the later refusal may respond to antidepressants or appetite stinuiLmts.

stages of dementia. As dementia progresses a person's Swallowing difTiculties can be minimized by adjustment

cognitive and communication abilities decline and it of diet texture and replacing thin with thickened fluids

becomes harder to ascertain accurately the wishes and (Treloar, 2007).

needs of the person (Shuster, 2000). Communication

problems also hinder the identification of hunger, pain Artificial hydration and nutrition

and concurrent illness. Practitioners need to be trained The most common form ot medical treatment for problems

in conmiuniciiting with people with dementia if effective with eating and drinking is artificial hydration and nutrition

end-of-life care is to be provided. such as percutaneous endoscopie gastrostomy, nasogastric

tubes and subcutaneous infusions. However, in people with

Pain dementia, artificial hydration and feeding when compared

Although pain is not an obvious symptom of advanced with hand-feeding has no evident benefits in terms of survival

dementia, it is miportant to remember that people with (Meir et al, 2001). Artificial feeding does not reduce the risk

dementia may sufier pain üroni coiiiorbid conditions such as of aspiration pneumonia infections, pressure sores, or offset the

arthritis or peripheral neuropathy. It is useful to obtain a pain effects of malnutrition (Finucane et al, 1999). Despite research

history from the person with dementia and their caregiver. su^esting little or no benefit, up to 44% people with dementia

People with dementia may be unable to conceptuaUze pain die with feeding mbes in situ (Gillick, 2000). The Alzheimer's

due to visuospatial deficits caused by the dementia, and thus Society (2007) does not consider the use ofa tube for artificial

it is useful to look at non-verbal indicators, such as facial hydration and feeding as best practice in the advanced stages ot

expression, tense body language and agitated bebaviour. dementia. C'aregivers need to be supported in understanding

The Assessment of Discomfort in Dementia protocol the potentiai complications associated with tubes and the

is designed to assess and treat pain and discomfort, and appetite changes associated with advanced dementia.

guides the user through a physical and medical assessment

of possible sources of pain and discomfort (Kovach, 2003). Infection

The Abbey Pain Scale is a brief assessment scale for people Infections are an unavoidable consequence of advanced

with end-stage dementia. The scale consists of six items dementia due to an inability to report symptoms, decreased

(e.g. physiological changes, physical changes) with four immune responses to infections and loss of ability to ambulate

response modalities scored from 0 (absent) to 3 (severe), (Robinson et al. 2005). However, the effectiveness of antibiotic

with a range for the total scale of 0-18 (Abbey et al, 2004). therapy is limited by the recurrent nature of infections in

The Royal College of Physicians et al (2007) have issued advanced dementia. The use of antibiotics in people with

comprehensive guidance on the assessment of pain in older advanced dementia should take into consideration the

people and highlights the challenges of identifying pain in recurrent nature of infections, which are caused by persistent

310 Lintisii lourii.ll ii!" Niirsjiig. 2U(I«.V()I 17, Nii S

swallowing difficulties with aspiration, and by other factors, such as selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs),

such as poor fluid intake and dehydration, predisposing should be considered as they have fewer side-effects and are

for development of infections that significantly reduces shown to have good efficacy (Doody et al, 2001).

the benefits of antibiotic therapy (Vblicer et al, 1998). The Up to 40% of people with dementia suffer from

palliative use of antibiotics should he considered on an psychosis (National Council for Palliative Care and

individual patient basis (NICE, 2006), Alzheimer's Society, 2006). It is often the cause of

behavioural disruption. Despite the increased risk of stroke

Fever and possible deleterious cognitive effect, antipsychotics

Fever should be clinically assessed. Consider treatments such (such as risperidone and olanzapine) are the only effective

as simple analgesics, antipyretics and mechanical coohng treatment for psychosis, and if it is severely distressing

(NICE, 2006). then It should be treated (Treloar, 2007). In a recent

study of people with advanced dementia who were cared

Depression and psychosis for at home until they died, it was antipsychotics and

The incidence of depression is high in advanced dementia antidepressants that were rated as more useful than any

(National Council for Palliative Care, 2006). Antidepressants, other class of medication {Treloar, 2007).

Case study 1. Care of the person with advanced dementia at home

Mrs T is a 73'year-old lady with Parkinson's disease and advanced dementia. She lives at home with her son, daughter-in-law ¡main carer) and her

two grandchildren. Mrs T is fuHy dependent for ail her activities of daily living. She is bed/chair bound and requires hoisting. She is incontinent of urine

and faeces. She has dysphagia and is at high risk of aspiration. Her pressure areas are intact (she has a pressure relieving cushion and mattress). She is

unable to communicate her wishes and has iost her grasp of English (her first language is Gujarat and she may respond to a few words spoken in her

native tongue). She loves being around her family and enjoys regular massage sessions at home, Mrs T fulfils the criteria for NHS Continuing Care.

She has a care package consisting of two carers three times a day to attend to her personal care, perform pressure area care and address toileting

needs. Mrs T's daughter-in-law. Sema, administers her medication and manages her feeding (Mrs T requires feeding and can only take fortified liquid

supplements because of her dysphagia), and also attends to her elimination and psychosocial needs at all other times. Mrs T used to attend the local

memory clinic (she presented to clinic at an advanced stage of dementia), but as her condition has progressed, the dementia nurse specialist (DNS) and

Alzheimer's support worker visited her at home on a regular basis to provide support for her and the family. On a recent visit to the family, the DNS

explored end-of-life issues with them. They expressed the wish for her to stay at home and die peacefully when the time comes. Sema and her husband

expressed concerns regarding the wish to avoid hospital admission if at all possible, the wish to avoid tube-feeding, and the need for intensive and

immediate medical support and advice when required. The fear of not knowing what to do if Mrs T started to exhibit distressing symptoms was a major

concern for the family.

Case-conference

The DNS organized a case-conference to explore and discuss the palliative care needs of Mrs T and her family. Present at the case-conñerence was:

• Sema

• DNS

• GP

• District nurse

• Community matron

• Speech and language therapist (SALT)

• Care agency manager

Professional roles

The care needs of Mrs T and her family were discussed, A written plan of care was formulated, which addressed care issues and the family's concerns,

and set out each person's professional roles and responsibiiities:

• GP - review medication and reduce amount of tablets if indicated. GP also offered to speak to Sema by telephone (and visit as necessary) whenever

any medicai concerns arose

• SALT - assess swaiiow and provide advice on reducing risk of aspiration

• District nurses/community matron - assess pressure area risk and provide equipment as appropriate

• Community matron - provide contact detaiis to Sema and coordinate care of Mrs T, including review of care pian through regular contact

• Care agency manager - provide experienced carers and ensure there is continuity of care to enabie a rapport to be estabiished between caregivers

• DNS - refer Mrs T and Sema to local hospice home-care team to review Mrs T. support her famiiy and provide contact details; refer Mrs T to a

Parkinson's nurse speciaiist for review; speak to sociai services to request respite care at home for Sema {as she did not wish for her mother-in law

to go into a care home for respite); and to maintain regular contact with Mrs T and her famiiy aiong with the Alzheimer's support worker.

Mrs T's famiiy ailowed to advocate on her behalf, and were given the opportunity and support to explore end-of-life issues

Close collaboration and understanding across heaith and social care agencies

Formulation of a written care plan that is shared across agencies

Designated case manager who will regularly review care plan

312 Uriiish Joiirii:il ot ^ , 2lHIK,Viil 17, No 5

NEUROSCIENCE NURSING

Spiritual needs Case Study 1 highlights the benefits of a multidisciplinary

There is evidence to surest the spiritual needs of those approach to the care of a person with advanced dementia

dying with dementia are often ignored. In a recent study within the home environment.

that compared the case notes of patients with and without

dementia who died during acute hospital admission, Sampson Conclusion

et al (2IH)6) found signÍfR\mtly fewer p;itients with dementia Dementia is a progressive and incurable condition. Current

who made any mention of their rehgious faith. Spiritual needs evidence suggests that people with advanced dementia do

go beyond attention to religious practice, and practitioners not have equity of access to specialized palliative care services

may tieed to find out a person's spiritual needs by talking to (Audit Commission, 2002). There have been a number of

their carer if communication is difficult. recent health policy documents and guidelines in the UK

emphasizing the need for improving the quality and access

Psychological needs of palliative care for all people, and for those with demetitia

I'tactitioncrs need to he sensitive to the psychological (Care Services Improvement Partnership, 2005; 1)H. 2005).

impact of advanced dementia on the person with the disease. The role of palliative care services for people with advanced

Moving a person with dementia from one environment to dementia has unfortunately heen underutilized up to now.

another, such as from a care home to an acute hospital The ethos of palliative care, however, is consistent with a

setting, can he traumatizing and provoke feelings of loss person-centred approach to care of people with dementia.

and separation that might manifest themselves as behaviour Health practitioners need to be able to recognize the

that challenges. clinical features of advanced dementia. Specific issues for

consideration in palliative care in advanced dementia include

Family caregivers hydration and nutrition,management ofpain.and management

To improve palliative care for people with dementia there of depression. It may he very difficult to communicate with a

needs to he greater comminiication with families and person with advanced dementia hut carers can be strong

proxies. They need to be given clear information about the advocates on their behalf. It is hoped that the MCA will

disease trajectory, complications of dementia and limited empower people with dementia to be able to make their

treatment options (Caplan et al. 2006). wishes and thoughts on their care in advanced stages of the

The progression of dementia confronts families and disease known. It will also give carers the legal right to make

proxies with difficult ethical and moral decisions, and welfare decisions on their behalf through a lasting power of

caregivers need to be supported through this difficult attorney. Good palliative care for those with advanced

period.There is also evidence to suggest that the more social dementia will be a multidisciplinary team approach that will

support carers receive pre-bereavetnent, the hetter adjusted not only consider the person with dementia but also support

they are post-bereavement (Schulz et al. 2003). their families and carers. UH

Recommendatlons for Improvements to care

11.iiKock ct al (2006) eke several ways m which care of

people with advanced dementia can be improved, namely: Abbey J, Piller N. De Bellis A ct al (2(>l)4) Tht- Abbey pain scale: a 1-minute

• The development of evidence-based guidelines to inform nunitricil indicator for people with end stage dementia, ¡nt J Polliat Nun

3

practice for people with advanced dementia, including Alzheimers Si>ciety (2(K)7) Palliative care/withdrawing and withholding

planning of goals early in disease trajectory, and feeding [rfatiiieiit. Position Staieiiieiic. Alzheimers Siiiicry, London. Available al:

http://0nyiirl.com/2kiJ4f (last acces.sed 5 March 2(H)8)

symptom management with emphasis placed on bereavement Aiitlit Commission (21)02) Forget Me Not: Devclopitig Mental Health Servías for

care for families Older l\opk ill England. Auclit CCommission, London

British National Formulary (2008) C:odeine Phospliatc. BNF 54. UMJ

• Increased awareness during the early stages of dementia of Publishinji Group Lid .md RPS Piitilishing, London

advance decisions Caplan CiA, MCIKT A. St|Uires B. i:iiaii S. Willctt W (2il0f.) Ad\'ancc care

pianning and hospital in the nursing home. i^,i;c .-H.Ci'iifi,' 35(6): 581-5

• More research into palliative care needs of people with Care Services Impnwement I'artnership (2l)0f>) ííii'i^'í'míylí Btisiiu-ss: liitcgmting

advanced dementia Mental Haillli Si-n-ias for Older .Adulty CSIl'. London

Clare L. Woods RJ {21H)4) Cognitive training and Cognitive training tor people

• Health providers to he educated about the need for with i-ariy stage Alzheimer's disease, a review. Neimfsychol Rehabiti 14(4):

palliative care, especially applying principles of palliative 385-401

Cox S, Cook A {2(K)2) Caring for people uith dementia at the end. In: Hocklt*y

care to advanced dementia J, Clark D, eds. Palliatiiv Care for Older People in ('are Homes. Open University

• A palliative care approach rather than specialist palliative Pres.s, Buckingham: 86-103

[>eparntifnt of Hfalth (2(X)4) Tlie NHS Improvement MMI: hitting People ¡it flu-

care services, and palliative care interventions which focus Ham of Pi'l'li'' Sfrt'iœs. HMSO. London

on pain .md symptom management and communication Departtnent of Health (20115) 77ic \'HS Bud of Ufi Care /^MIIIÍHC. H M S O ,

London. Available at: www.endofiifccare.iihs.iik/eolc (last acces.sed 29

regarding end-of-life issues. Consultation of specialists October 2CH17)

and multidisciplinary teams would encourageflexihleand l>fpartmtnt of Health (20()6a) (Sur Health Our Care Say: A New Dimtionfor

responsive service. Community Sewices. O H . London

Department of Health (2<)0()b) A Nein Amhiiion for Old Age: Next Steps in

• Continuity of care and collaboration between healthcare Impienietitin); the Natiotml Sen'ice Framework for Older People. HMSO. London

Doody RS. Stfvcns J C . Beck C et al (2001) Practice paramt-tcr: man.igniK'm

professionals is important for good quality palliative care of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quabiy Standards

• Communication between professional care providers and Subconimittt'e of the Amtrican Academy of N e u r o l t ^ . Nft'if/tTO' 56(9):

1154-^)6

families is critical to minimize the risk of conflicting EUershaw J, WilkiTison S (2003) Orr' of the DyiH.?; A Pathwity to Excellence.

opinions in management goals. Oxibnl University' Press. Oxford

iinii'.hj.iiirti.i! ofNiirMiii;. 2U(iK,Vd 17, Nu 5 313

^ MJ, Ekberg O, S e ^ L,Tully J (1992) Deglutition in elderly patienis Koopmans RT, Ekkerink JL, van Weel C (2iX)3) Survival to late dementia in

with demenna: findings of videofluoragraphic evaluation and impact on Dutch nursing home patients. ¡Am Ceriatr So( 51{2): Í84-7

staging and management. Radiology 183(3); 811-14 Kovach C R (2003) "The ones who can't complain" lessons learned about

Finucanc TE, Travis K, Christmas C (1999) Tube feeding in patients with discomfort and dementia. Alzheimer's Care Quarterly 4(1): 41-9

advanced dementia: a review of the evidence. JA.\L^ 282(14): Í36.S-7U Lloyd-Williams M, Payne S (20112) Can niulti-disciplinary guidelines impmve

Gillick M R (2(HI0) Rethinking the role of tube feeding in patients with the palliation symptoms in the terminal phase of dementia. Intj Palliât Niirs

advanced dementia. N EnfilJ Med 342(3); 2(16-10 )

Hancock K. Chang E, Johnson A et aJ (2006) Palliative care for people with McCarthy M.Addington Hall J, Altmann D (1997) The experience of dying

advanced dementia: The need for a collaborative, evidence-based approach. with dementia a retrospective saidy. Iritj Psychiatry 12(3): 404—9

Alzheimer's Care Quarterly 7(1): 49-57 Meir D, Ahronheim J, Morri.s J, Ha.skin-Lyons S, Morrison R (2001) High

Harris D (20()7) Forget me not: palliative care for people with dementia. short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia: lack

Postgrad MedJ 83(98(1): 362-6 of benefit of tube feeding. Arch Intern Mea 161(4); 594-9

Henderson J (20f>7) Palliative care in dementia: caring at home to the end. Mitchell S, Kiely D, Hamel M (2004) Dying with advanced dementia in the

Journal oj Dementia Care 15(3): 246 nursing home. Arch Intern Med 164(3); 321-6

Hughes JC, Jolley D, jonian A, Sampson EL (2(X)7) Palliative care in dementia: National Council for Palliative C^are and Alzheimer's Society (2006) Exploring

issues and evidence, .^(iiiioccï in Psychiatric Treatment 13: 251-60 PalHatiif Care for People u-ith Dmientia - a discussion document. NC'PA and

Kay DW, Forster DP, Newens AJ (201 )(l) Long-temi survival, place of death and AS, London

death certification in clinically diagnosed pa'-senile dementia in northern National Institute for Health and (Clinical Excellencf (2004) lmprovinf> Supportiiv

England. Follow-up afi:er S-12 years. BrJ Psychiatry 177; 156-62 and Palliatiiv Care for Adults wiih (dancer. N1C"E, London

Kitwood T (1997) Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Open National Institute for HeaJth and Clinical Excellence (2(K)6) Dementia.

University Press, Buckingham Supporting People with Deinentia and their Carers in Health and Social Care.

NICE. London

Robinson L. Hughes J. L)a!ey S, Ready J. Ballard C'.Volicer L (2005) End-of-life

care and dementia. Riv Clin Cerontol 15(2); 135—48

Royal College of General Practitioners (2006) Palliative C^are and the GMS

Contract: Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). Guidamc Paper

- 1st March o6. Version l.IO. RCXîP. London. A\-ailable at: http://tinyurl.

KEY POINTS com/34kc4c (last accessed 5 Marth 2()(}8)

Royal College of Physicians, British Geriatrics Society, British Pain Society

I Advanced dementia should be regarded as a terminal illness. (2007) Tlie Assessment, of Pain in Older l^ople: National Guidelines. Concise

guidance to good practice series Number H. H,CP, London

I There is unequal access to palliative care services for people with advanced Sampson EL, C>ould V, Lee, D Blanchard M R (2(M)6) Differences in care

received by patieni:s with and without dementia who died during acute

dementia. hospital admission; a retrospective case note smiiy. Age Ageing 35(2): 187—9

Schulz R. Mendelsohn Ali, Haley WE et al (2003) Énd-of-Íite care and the

effects of bereavement on family caregivers of persons with dementia. N Bng

I Pain is under-recognized in people with advanced dementia but the use of 7,Vící/349(20); 1936-42

screening tools and Improved skills in recognizing non-verbal signs of pain Shuster JL Jr (2000) Palliative care for advanced dementia. CViii Oriuir Med

16(2): 373-86

help to improve management of pain. Thomas K (2003) The gold standards fi-amework. GSF, Wakall. Available at:

www.goldstandardsfiumework.nhs.uk (last accessed 29 October 2iX)7)

I Practitioners should ideally discuss certain issues with the person with Treloar A (2(XJ7) What can old age psychiatry do? Old Aqe Psychiatrist. Spring

45: 9

dementia while they stiii have capacity, such as advanced statements. Volicer L, Brandeis G, Hurley A. Bishop C, Kern D. Karon S (199H) Infections 111

preferred piace of care plan and lasting power of attorney. advanced dementia; In:Volicer L, Hurley A. eds. Hospice Carr for Patients with

Advanced Progrfssitv Detnentia. Springer, New York: 2*i—47

World Health Organization (1990) Cancer Pain Rcliejand Palliatitv Ciire.WHO,

I Peopie with advanced dementia deserve the same quality of palliative care Geneva

as people with other terminal diseases. World Health Organization (2004) Better Ihlliativc Care for Older People.^HO,

Geneva

World Health Organization (2(M)6) W H O s Pain Udder. W H O , Geneva.

Available at: http;//tinyurLcom/35akc3 (last accessed 5 March 2008)

CALL FOR PAPERS

The B|N welcomes unsolicited articles on a range of clinical

issues. ALL manuscripts should be submitted to our online

article submission system, Epress, at:

w\AAA/.epress.ac.uk/bjn/webforms/author.php

(please note that all articles are subject to external,

double-blind peer review).

If you have any queries or questions regarding

submitting an articie to the journal please contact

Asa Bailey, Editor, at: asa@markallengroup.com

314 British Journal ot g, 2(IUH,Vul 17. No 5

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Health Care Disparities and The HomelessDocument6 paginiHealth Care Disparities and The Homelessapi-520141947100% (1)

- 14 Essentials To Assessment and Care PlanMT2013!08!018-BRODATY - 0Document9 pagini14 Essentials To Assessment and Care PlanMT2013!08!018-BRODATY - 0Danielcc Lee100% (1)

- Curran, Stephen - Wattis, John-Practical Management of Dementia - A Multi-Professional Approach, Second Edition-CRC Press (2016)Document270 paginiCurran, Stephen - Wattis, John-Practical Management of Dementia - A Multi-Professional Approach, Second Edition-CRC Press (2016)Sang LyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Therapeutic Advances and Risk Factor Management: Our Best Chance To Tackle Dementia?Document3 paginiTherapeutic Advances and Risk Factor Management: Our Best Chance To Tackle Dementia?ABC Four CornersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Demencia Vascular Farmacoterapia 2017Document18 paginiDemencia Vascular Farmacoterapia 2017Citlalli RmzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taking CareDocument333 paginiTaking Care4imÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transition of CareDocument7 paginiTransition of CareJisna Alby100% (1)

- Geriatric Care TreatmentDocument332 paginiGeriatric Care TreatmentHamss Ahmed100% (1)

- Choosing Wisely Master ListDocument92 paginiChoosing Wisely Master ListrobertojosesanÎncă nu există evaluări

- CDC Travel SlidesDocument35 paginiCDC Travel Slidesxtreme_1m100% (1)

- Sem 11 Cardiovascular System & Dental ConsiderationsDocument143 paginiSem 11 Cardiovascular System & Dental ConsiderationsJyoti Pol SherkhaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psych HX, MSEDocument4 paginiPsych HX, MSELana AngelicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Use of Sedation in Palliative CareDocument13 paginiUse of Sedation in Palliative Careuriel_rojas_41Încă nu există evaluări

- Ott - Nurs 7003 - ReumeDocument3 paginiOtt - Nurs 7003 - Reumeapi-547116013Încă nu există evaluări

- Palliative CareDocument70 paginiPalliative CareTakara CentseyyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Overview of Practice of Consultation Liaison.4Document10 paginiOverview of Practice of Consultation Liaison.4Sweet Memories JayaVaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cure Palliative 1Document64 paginiCure Palliative 1Mr. LÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vulnerable PopulationsDocument5 paginiVulnerable Populationsapi-250046004100% (1)

- Reiki Therapy Reduces HypertensionDocument34 paginiReiki Therapy Reduces HypertensionYayu AlawiiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dementia Care 1 Guidance AssessmentDocument9 paginiDementia Care 1 Guidance Assessmentdogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Seizures in Children JULIO 2020Document29 paginiSeizures in Children JULIO 2020Elizabeth HendersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geriatrics Trauma Power Point Presentation Dr. BarbaDocument23 paginiGeriatrics Trauma Power Point Presentation Dr. BarbagiscaamiliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preventive Care Checklist Form ExplanationsDocument3 paginiPreventive Care Checklist Form ExplanationsKak KfgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peripheral Vascular Medicine - Dr. Deduyo PDFDocument14 paginiPeripheral Vascular Medicine - Dr. Deduyo PDFMedisina101Încă nu există evaluări

- Case 36 AscitesDocument4 paginiCase 36 AscitesMichaelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nur 330 Health PromotionDocument14 paginiNur 330 Health Promotionapi-598192448Încă nu există evaluări

- HOSPICE CARE: A TEAM APPROACH TO COMPASSIONATE END-OF-LIFE CAREDocument7 paginiHOSPICE CARE: A TEAM APPROACH TO COMPASSIONATE END-OF-LIFE CAREJason SteelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research in Palliative Care PresentationDocument20 paginiResearch in Palliative Care PresentationNICKY SAMBOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Format & Guide to Oral Case PresentationsDocument10 paginiFormat & Guide to Oral Case PresentationsZainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vascular Surgery Clinic Soap NoteDocument2 paginiVascular Surgery Clinic Soap Noteapi-285301783Încă nu există evaluări

- Keeping Older Adults Safe at Home: Fall Risks Add UpDocument6 paginiKeeping Older Adults Safe at Home: Fall Risks Add UpBj DuquesaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Depression Care PathwayDocument267 paginiDepression Care PathwaydwiÎncă nu există evaluări

- End of Life CareDocument11 paginiEnd of Life CareBelindaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper: Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument13 paginiResearch Paper: Alzheimer's DiseaseABC Four CornersÎncă nu există evaluări

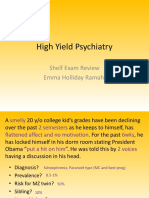

- High Yield Psychiatry Shelf Exam ReviewDocument43 paginiHigh Yield Psychiatry Shelf Exam ReviewEdgar SotoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Care Disparities - Stereotyping and Unconscious BiasDocument39 paginiHealth Care Disparities - Stereotyping and Unconscious BiasCherica Oñate100% (1)

- Module Guide For Palliative Care AssessmentDocument83 paginiModule Guide For Palliative Care AssessmentAnd ReiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evidence-Based Answers To Clinical Questions For Busy CliniciansDocument28 paginiEvidence-Based Answers To Clinical Questions For Busy CliniciansMohmmed Abu Mahady100% (1)

- To Severe Dementia in Long-Term CareDocument14 paginiTo Severe Dementia in Long-Term Care2gether fanmeet100% (1)

- Coroners Case - Role of The NurseDocument18 paginiCoroners Case - Role of The NurseGUrpreet SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pediatrics 04: 8-Year-Old Male Well-Child Check: Learning ObjectivesDocument8 paginiPediatrics 04: 8-Year-Old Male Well-Child Check: Learning ObjectivesJeffÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Origins and Auspices of Hospice ArticleDocument10 paginiThe Origins and Auspices of Hospice ArticleDr.Max DiamondÎncă nu există evaluări

- MENTAL HEALTH ASSESSMENTDocument3 paginiMENTAL HEALTH ASSESSMENTJustine UyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geriatrics Sir ZahidDocument575 paginiGeriatrics Sir ZahidSheeraz ShahzadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of Bone Fractures Classification GuideDocument8 paginiTypes of Bone Fractures Classification GuideApple PaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Training Manual On How To Teach Medical EthicsDocument33 paginiTraining Manual On How To Teach Medical EthicsghaiathmeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perioperative Medicine Managing Surgical Patients With Medical Problems by Chikwe, Joanna Walther, Axel Jones, PhilipDocument462 paginiPerioperative Medicine Managing Surgical Patients With Medical Problems by Chikwe, Joanna Walther, Axel Jones, PhilipIbrahim AlmohiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethical Dilemma Debate - Assisted SuicideDocument23 paginiEthical Dilemma Debate - Assisted SuicidepetitepetalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Limb Ischemia SiteDocument23 paginiAcute Limb Ischemia Sitebenypermadi100% (1)

- Nnaples - Heart Disease Final Term PaperDocument11 paginiNnaples - Heart Disease Final Term Paperapi-523878990100% (1)

- Royal College of Nursing 2020Document11 paginiRoyal College of Nursing 2020Alexandra Olortegui MendietaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liverpool Care Pathway PDFDocument63 paginiLiverpool Care Pathway PDFBryan DorosanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive Disorders Due to Medical ConditionsDocument18 paginiCognitive Disorders Due to Medical ConditionsSri HazizahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heart Disease Research Paper Final DraftDocument13 paginiHeart Disease Research Paper Final Draftapi-301442453Încă nu există evaluări

- Pocket Guide To 2015 Beers Criteria PDFDocument7 paginiPocket Guide To 2015 Beers Criteria PDFYuliEdySeringnyungsepÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Safety Standards Mental Health PDFDocument201 paginiPatient Safety Standards Mental Health PDFRita RibeiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- FOOT HEALTH FOR THE HOMELESSDocument41 paginiFOOT HEALTH FOR THE HOMELESSLyanne Daisy Duarte-VangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palliative care in Parkinson's diseaseDocument4 paginiPalliative care in Parkinson's diseaseAnonymous lwYEylQhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Day 1 - Common Session 2 - Palliative Care and Its Concept - DR Sushma BhatnagarDocument39 paginiDay 1 - Common Session 2 - Palliative Care and Its Concept - DR Sushma Bhatnagarm debÎncă nu există evaluări

- End-Of-Life Care in The Icu: Supporting Nurses To Provide High-Quality CareDocument5 paginiEnd-Of-Life Care in The Icu: Supporting Nurses To Provide High-Quality CareSERGIO ANDRES CESPEDES GUERREROÎncă nu există evaluări

- SECTION 5 - Diagnostic Criteria For DementiasDocument3 paginiSECTION 5 - Diagnostic Criteria For Dementiasdogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Dementia Symptoms Diagnosis ManagementDocument7 paginiDementia Symptoms Diagnosis Managementdogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Person-Directed Dementia Care Assessment ToolDocument54 paginiPerson-Directed Dementia Care Assessment Tooldogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Neuro-Pathological Effects of Alcohol and SolventsDocument4 paginiNeuro-Pathological Effects of Alcohol and Solventsdogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Dementia Care. Part 2 Understanding and Managing Behavioural ChallengesDocument7 paginiDementia Care. Part 2 Understanding and Managing Behavioural Challengesdogstar23100% (2)

- Evaluation of The NINCDS-ADRDA CriteriaDocument6 paginiEvaluation of The NINCDS-ADRDA Criteriadogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Mild Cognitive Impairment in Older PeopleDocument8 paginiMild Cognitive Impairment in Older Peopledogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Management of Severe Alzheimer DiseaseDocument10 paginiManagement of Severe Alzheimer Diseasedogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Dementia Care 1 Guidance AssessmentDocument9 paginiDementia Care 1 Guidance Assessmentdogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Alcohol Intake and Risk of DementiaDocument8 paginiAlcohol Intake and Risk of Dementiadogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Diagnostic Criteria For AD and FTDDocument2 paginiClinical Diagnostic Criteria For AD and FTDdogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Subjective Memory Deterioration and Future DementiaDocument8 paginiSubjective Memory Deterioration and Future Dementiadogstar23Încă nu există evaluări

- Manage Odontogenic Infections Stages Severity AntibioticsDocument50 paginiManage Odontogenic Infections Stages Severity AntibioticsBunga Erlita RosaliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PR Menarini PDX Ab RBCDocument2 paginiPR Menarini PDX Ab RBCvyasakandarpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 6 DiscussionDocument3 paginiChapter 6 DiscussionyughaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health Personal Statement - Docx'Document2 paginiMental Health Personal Statement - Docx'delson2206Încă nu există evaluări

- BellDocument8 paginiBellZu MieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutrition Care Process NoteDocument3 paginiNutrition Care Process Noteapi-242497565Încă nu există evaluări

- Week - 4 - H2S (Hydrogen Sulfide) Facts W-Exposure LimitsDocument2 paginiWeek - 4 - H2S (Hydrogen Sulfide) Facts W-Exposure LimitsLọc Hóa DầuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Example of SpeechDocument9 paginiExample of SpeechDanville CoquillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consultant Physician Gastroenterology Posts Clyde SectorDocument27 paginiConsultant Physician Gastroenterology Posts Clyde SectorShelley CochraneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gems of Homoepathic Materia Medica J D Patil.01602 - 2belladonnaDocument7 paginiGems of Homoepathic Materia Medica J D Patil.01602 - 2belladonnaPooja TarbundiyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Safety Data Sheet: Ultrasil® VN 3 (Insilco)Document6 paginiSafety Data Sheet: Ultrasil® VN 3 (Insilco)Bharat ChatrathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Renal Regulation of Extracellular Fluid Potassium ConcentrationDocument32 paginiRenal Regulation of Extracellular Fluid Potassium ConcentrationDaniel AdamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen PlanusDocument1 paginăA Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen Planus600WPMPOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Pulmonary Rehabilitation On Physiologic and Psychosocial Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDocument10 paginiEffects of Pulmonary Rehabilitation On Physiologic and Psychosocial Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseElita Urrutia CarrilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- End users' contact and product informationDocument3 paginiEnd users' contact and product informationمحمد ہاشمÎncă nu există evaluări

- Student study on family health and pregnancy in rural ZimbabweDocument3 paginiStudent study on family health and pregnancy in rural ZimbabweTubocurareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Canadian Standards For Hospital LibrariesDocument4 paginiCanadian Standards For Hospital LibrariesFernando HernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- EEG ArtifactsDocument18 paginiEEG ArtifactsNazwan Hassa100% (1)

- Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: Florian Daniel Zepf, Caroline Sarah Biskup, Martin Holtmann, & Kevin RunionsDocument17 paginiDisruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: Florian Daniel Zepf, Caroline Sarah Biskup, Martin Holtmann, & Kevin RunionsPtrc Lbr LpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pediatric PerfectionismDocument20 paginiPediatric Perfectionismapi-438212931Încă nu există evaluări

- HAADStatisticsEng2013 PDFDocument91 paginiHAADStatisticsEng2013 PDFHitesh MotwaniiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Generic Pharmacy (Powerpoint)Document7 paginiThe Generic Pharmacy (Powerpoint)Ronelyn BritoÎncă nu există evaluări

- DylasisDocument3 paginiDylasisyuvi087Încă nu există evaluări

- Reflection Paper-Culture, Spirituality, and InstitutionsDocument4 paginiReflection Paper-Culture, Spirituality, and Institutionsapi-359979131Încă nu există evaluări

- Rangkuman by Yulia VionitaDocument21 paginiRangkuman by Yulia VionitaRizqi AkbarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neonatal Thrombocytopenia: An Overview of Etiologies and ManagementDocument21 paginiNeonatal Thrombocytopenia: An Overview of Etiologies and ManagementbidisÎncă nu există evaluări

- PCI-DPharm Syllabus Guidelines 2020Document30 paginiPCI-DPharm Syllabus Guidelines 2020Chander PrakashÎncă nu există evaluări

- English 2 Class 03Document32 paginiEnglish 2 Class 03Bill YohanesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Material Safety Data Sheet: Tert-Amyl Alcohol MSDSDocument6 paginiMaterial Safety Data Sheet: Tert-Amyl Alcohol MSDSmicaziv4786Încă nu există evaluări

- JMDH 400734 Application Benefits and Limitations of Telepharmacy For PDocument9 paginiJMDH 400734 Application Benefits and Limitations of Telepharmacy For PIrma RahmawatiÎncă nu există evaluări