Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Brown - Narcissism, Identity, and Legitimacy PDF

Încărcat de

Whatever ForeverDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Brown - Narcissism, Identity, and Legitimacy PDF

Încărcat de

Whatever ForeverDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Narcissism, Identity, and Legitimacy Author(s): Andrew D. Brown Source: The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 22, No.

3 (Jul., 1997), pp. 643-686 Published by: Academy of Management Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/259409 . Accessed: 08/01/2011 15:12

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aom. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Academy of Management is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Academy of Management Review.

http://www.jstor.org

Academy of Management Review 1997, Vol. 22, No. 3, 643-686.

AND LEGITIMACY NARCISSISM,IDENTITY,

ANDREW D. BROWN University of Cambridge

The theory of narcissism can be employed usefully to analyze the dynamics of group and organizational behavior. Just as individuals seek to regulate their self-esteem through such ego-defense mechanisms as denial, rationalization, attributional egotism, sense of entitlement, and ego aggrandizement, which ameliorate anxiety, so too do groups and organizations. An understanding of the behaviors by which groups and organizations regulate self-esteem is important, because it sheds light on the dynamics underlying the legitimacy attributions made by organizational participants. In this article I enlarge and illustrate these arguments.

Ideas ... gain their value from what they allow us to see in organizations.Evocative ideas need to be cultivated by theorists fromthe beginning because belief, not skepticism, precedes observation.... If believing affects seeing, and if theories are significant beliefs that affect what we see, then theories should be adopted more to maximise what we see than to summarise what we have already seen. (Weick, 1987:122) "Narcissism" is an important label that permits us to group cognitions and behaviors, which have, as their common factor, a role to play in the regulation of self-esteem. Although the theory of narcissism most usually is applied at the level of the individual, it also can be usefully employed to inform our understanding of group and organizational behavior. Individuals, groups, and organizations possess identities that are preserved through individual and social processes of self-esteem regulation. Selfesteem is narcissistically regulated through ego-defense mechanisms, such as denial, rationalization, attributional egotism, sense of entitlement, and ego aggrandizement. In organization studies the concept and theory of narcissism can be used to deepen our understanding of both group and organization identity and the dynamics underlying the legitimacy attributions made by organizational participants and external institutions. The theory of narcissism provides us with a lens for understanding organized activity-the research utility of which is at least twofold. First,

The insightful comments of Nick Bacon, Susan Bartholomew, John Child, Graeme Currie, Geoff Eagleson, John Hendry, Nick Oliver, John Roberts, Mick Rowlinson, Susan Jackson, and five anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged. 643

644

Academy of Management

Review

July

narcissism is a potentially valuable organizing label that permits us to make a connection between what we previously have considered disparate aspects of organized activity (e.g., denial, rationalization, attributional egotism, self-aggrandizement, and sense of entitlement). In turn, this suggests that research on, for example, corporate concealment (Abrahamson & Park, 1994), escalation of commitment (Staw, 1980), causal reasoning (Bettman & Weitz, 1983; Salancik & Meindl, 1984; Staw, McKechnie, & Puffer, 1983), and uniqueness claims (Martin, Feldman, Hatch, & Sitkin, 1983; Selznick, 1957) are linked more intimately than we have recognized to date. At a time when our understanding of organization is becoming increasingly fragmented (Martin, 1992; Reed & Hughes, 1992), the integrative power of the narcissism concept may in itself be deemed valuable. Second, viewing organizations as narcissistic entities provides us with a further perspective, focusing on the importance of self-esteem regulation as it is achieved through various ego-defense mechanisms. Various authors have described organizations as systems (Burns & Stalker, 1961; Trist & Bamforth, 1951), theaters (Mangham & Overington, 1983), socially constructed cultures (Pettigrew, 1979), and political arenas (Pfeffer, 1981; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). The already substantial literature on self-esteem (Brockner, 1988; Cohen, 1959; Erez & Earley, 1993; Festinger, 1954; Maslow, 1954; Ring & Van de Ven, 1989; Staw, 1980) suggests that the concept of organizations as social entities for the regulation of self-esteem deserves to be considered alongside those more conventional perspectives focusing on information, power, efficiency, and meaning. In this article I pursue these arguments in five major sections. First, I construct a concept of narcissism that can be operationalized in an organizational context. In the second section I employ Tajfel and Turner's (1986) theories of social identity to demonstrate the applicability of the identity concept to groups and organizations. Third, I exemplify the narcissistic tendencies of individuals, groups, and organizations. In the fourth section I outline a theory of group and organizational legitimacy in which the notions of self-esteem and narcissism are crucially implicated. Finally, I draw some conclusions regarding the potential of the issues discussed for further research. NARCISSISM Derived from the Greek myth of Narcissus, the concepts of "self" and "narcissism" in modern psychoanalysis have their origins in Freud's (1914) On Narcissism: An Introduction (Fine, 1986: 294). For Freud, narcissism referred to a state of being the center of a loving world in which the individual could act spontaneously and purely out of desire. Since we once experienced this state as infants, as adults we project the possibility of our returning to narcissism by means of the "ego ideal" (i.e., our model of the person that we must become in order for the world to love us as it did when we were young). Given that mortality, vulnerability, and limitation are existential facts of the human situation of each individual

1997

Brown

645

(Becker, 1973; Lichstenstein, 1977), no individual can ever in reality attain the ego ideal. In our attempts to realize our ego ideal, and thus to preserve our sense of self, we are assisted by ego-defense mechanisms. The suggestion here is that we can employ these predispositions, together with the notion of anxiety, to define the narcissistic personality for use in organization studies. Central to the theory of narcissism outlined here is the idea that individuals have a need to maintain a positive sense of self, and they engage in ego-defensive behavior in order to preserve self-esteem (Banaji & Prentice, 1994; Erez & Earley, 1993; Greenwald, 1980; Ring & Van de Ven, 1989). A "need" may be defined as "an internal state of disequilibrium or deficiency which has the capacity to trigger a behavioral response" (Steers & Porter, 1991: 97). "Self-esteem" is defined here "as the degree of correspondence between an individual's ideal and actual concepts of him[her]self" (Cohen, 1959: 103). Self-esteem, thus, is tied intimately to an individual's self-representation-to one's opinion of and respect for oneself. A separate motivation for self-knowledge also has been identified (Banaji & Prentice, 1994). Although the need for self-esteem largely is uncontested, it is important to note that there are considerable differences in the degree to which individuals exhibit self-esteem and that these can have important implications for behavior (Baumeister, Tice, & Hutton, 1989; Baumeister, Heatherton, & Tice, 1993; Baumgardner, Kaufman, & Cranford, 1990; Brockner, 1988; Brown, Collins, & Schmidt, 1988; Campbell, 1990; Rhodewalt, Morf, Hazlett, & Fairfield, 1991; Schlenker, Weigold, & Hallam, 1990). For example, high esteem is associated with a preference for ego defenses that repress, deny, or ignore challenges, whereas lowesteem individuals are more open to social influence (Brockner, 1988; Cohen, 1959; Hovland & Janis, 1959). Since 1914, the concept of narcissism has undergone "many changes in meaning" (Cooper, 1986: 112) and has "suffered terminologic slippage and overinclusiveness" to the extent that the term now lacks specificity (Goren, 1995: 339). Part of the problem is that Freud's original ideas on narcissism contained "contradictions, inconsistencies and gaps" (Teicholz, 1978: 833), allowing later authors to exploit the concept in pursuit of their own theorizing. As Pulver asserts, "In the voluminous literature on narcissism, there are probably only two facts on which everyone agrees: first that the concept of narcissism is one of the most important contributions of psychoanalysis; second, that it is one of the most confusing" (1970: 319). How then is the narcissistic personality to be defined? This is, as Lasch argues, a key issue not just because the idea is "readily susceptible to moralistic inflation" but because of the tendency to describe as narcissistic "everything selfish and disagreeable" (1978: 32). Based on Akhtar and Thompson (1982), the American Psychiatric Association (1980, 1986), Bromberg (1986), Emmons (1987), Fine (1986), Freud (1914, 1955), Frosh (1991), Gabriel, Critelli, and Ee (1994), Kernberg (1966), Kohut (1971), Lax (1975), Reich (1960), Rhodewalt and Morf (1995), Rothstein (1980), Shengold (1995),

646

Academy of Management

Review

July

Tobacyk and Mitchell (1987), and Westen (1990), among others, one can summarize the characteristics of the narcissistic personality in terms of six broad behavioral/psychological predispositions: (1) denial, (2) rationalization, (3) self-aggrandizement, (4) attributional egotism, (5) sense of entitlement, and (6) anxiety. Individuals engage in these behaviors unselfconsciously, rather than for the benefit of an intended audience (internal or external), in response to a deeply felt need to preserve selfesteem. This is, like all characterizations of the narcissistic personality, a contestable construct. In its defense it can be argued that it reflects significant areas of consensus in the literature and it lends itself to being operationalized in an organizational context. Denial has been described as "a primitive and desperate unconscious method of coping with otherwise intolerable conflict, anxiety, and emotional distress or pain," which can lead to increased confidence and feelings of invulnerability (Laughlin, 1970: 57). The narcissistic personality often is characterized by the denial of a difference between the ideal and actual self. Through denial, narcissistic individuals seek to disavow or to disclaim awareness, knowledge, or responsibility for faults that might otherwise attach to them (Gabriel et al., 1994; Lax, 1975; Rothstein, 1980; Shengold, 1995). Rationalization is an individual's attempt to justify or find reasons for unacceptable behavior or feelings and thus present them in a form consciously tolerable and acceptable. This mechanism involves a measure of self-deception, which is required in order to make what is consciously repugnant appear more creditable (Laughlin, 1970: 251). For the narcissistic personality, the resort to rationalization may involve the (unconscious) alteration of meanings of people, things, and events when self-esteem is threatened (Akhtar & Thompson, 1982; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995). Self-aggrandizement refers to a general tendency of an individual to overestimate his or her abilities and accomplishments (American Psychiatric Association, 1980, 1986; Shengold, 1995; Tobacyk & Mitchell, 1987; Westen, 1990). Such overestimates often are described as fantasies, which are emotionally significant unconscious wishes for fulfillment or gratification (Laughlin, 1970: 110). In the narcissistic personality these fantasies may be accompanied by extreme self-absorption, a tendency toward exhibitionism, claims to uniqueness, and a sense of invulnerability. A further manifestation of this need for self-enhancement is an individual's tendency to distort reality through selective perception. For example, an individual might judge others on personally relevant criteria only, selectively seek out positive information about themselves, and selectively remember events that support their self-concept (Gecas, 1982; Markus & Wurf, 1987; Wood, 1989). Attributional egotism refers to the tendency of an individual to offer explanations for events that are "self-serving" or "hedonic" and that typically involve the attribution of favorable outcomes to causes internal to the self and unfavorable outcomes to external causes (Bettman & Weitz,

1997

Brown

647

1983; Bradley, 1978; Dunning & Cohen, 1992; Dunning, Meyerowitz, & Holzberg, 1989; Dunning, Perie, & Story, 1991; Greenwald, 1980; Hill, Smith, & Lewicki, 1989; Miller & Ross, 1975; Staw, 1980; Zuckerman, 1979). The idea that narcissists likely will display attributional egotism and thus make self-serving attributions to protect vulnerable self-esteem generally is acknowledged (Brown & Rogers, 1991; Emmons, 1987; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995; Tennen & Herzberger, 1987; Westen, 1990). Kunda (1987) has suggested an alternative explanation of attributional egotism: it is the result of cognitive bias in the search for and mental processing of information, rather than ego defensiveness. Although it seems likely that both accounts of the causes of attributional egotism are valid, my emphasis in this article is on attributional egotism as it relates to the preservation of self-esteem. The narcissist's sense of entitlement often is associated with both a strong belief in his/her right to exploit others and an inability to empathize with the feelings of others (American Psychiatric Association, 1980, 1986; Lasch, 1978). Somewhat curiously, the narcissist's lack of interest and empathy for others is accompanied by an insatiable eagerness to obtain their admiration and approval (Reich, 1960). The narcissist, thus, is faced with the dilemma that she/he "holds in contempt and perhaps feels threatened by the very individuals upon whom he or she is dependent for positive regard and affirmation" (Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995: 18). Most of the other aspects of the narcissistic personality, such as denial, rationalization, attributional egotism, and especially self-aggrandizement, bolster this predisposition. Anxiety is not an ego-defense mechanism but what the ego-defense mechanisms are designed to ameliorate. The idea that narcissists suffer from feelings of dejection, worthlessness, and hypochondria (Reich, 1960); are despairing, empty, and fragile (Bromberg, 1986; Miller, 1986); and are hypersensitive and fraught with feelings of worthlessness (Akhtar & Thompson, 1982) is well documented (Rothstein, 1980). Lasch admirably captures this aspect of the narcissistic personality when writing that the narcissist "cannot live without an admiring audience. His apparent freedom from family ties and institutional constraints does not free him to stand alone or to glory in his individuality. On the contrary it contributes to his insecurity" (1978: 10). These traits define the narcissistic personality in general terms, but a fundamental distinction must be made between "normal" or "healthy" narcissism on the one hand and "pathological" narcissism on the other. It is important to note that "narcissism per se is a normal phenomenon" (Reich, 1960: 45) and "a universal and healthy attribute of personality" (Cooper, 1986: 115), which represents a "healthy concern with the self and with self-esteem regulation" (Frosh, 1991: 75). In short, "we all have some degree and variety of narcissistic delusion" (Shengold, 1995: 29; see also, Freud, 1914; Kohut, 1971; Rothstein, 1980). Normal or healthy narcissism implies, for example, that the ego is relatively stable, that the

648

Academy of Management Review

July

satisfactions gained from fantasies are not too great, and that the fantasies' content is not too divorced from reality (Fine, 1986). Indeed, some theories of narcissism suggest that narcissism is required for creativity, empathy with others, and the acceptance of death (Frosh, 1991: 96). Taken to one of two extremes, however, narcissism can constitute a pathological disorder that interferes with individuals' abilities to function adequately or to form meaningful relationships with others. Excessive self-esteem, for instance, implies ego instability and engagement in grandiose and impossible fantasies serving as substitutes for reality. Inadequate self-esteem, the other extreme, is likely to be associated with hypersensitivity, hypochondria, insecurity, and fear of death. Thus, narcissism ranges along a continuum, with the two extremes associated with pathological conditions. The dividing point between what constitutes healthy and what is pathological at either end of the spectrum requires a subjective evaluation. In this article I focus on narcissism in organizations as defined by the six general categories listed above, largely without attempting to arbitrarily sort the healthy from the pathological. However, I take up the healthy versus pathological debate again in the Discussion. For organization studies, the concept of narcissism opens up interesting avenues for research at the level of the individual, the group, the organization, and society. Perhaps least contentiously, narcissism can be employed as a psychoanalytic concept to explain the behavior of individuals in organizations. Although scholars of organization rarely have implicated the concept directly (exceptions include Kets de Vries & Miller, 1985, and Sankowsy, 1995), some scholars have paid considerable attention to attributes of the narcissistic personality and, more typically, the need for self-esteem (Bass, 1981; Bass & Coates, 1953; Feinberg, 1953; Gilchrist, 1952; Heynes, 1950; Lippit, Thelen, & Leff, undated; Sherif & Sherif, 1953; Sherif, White, & Harvey, 1955; Van Zelst, 1951; Whyte, 1943). My primary objective in this article is the application of the narcissism concept to groups and organizations and, specifically, the descriptive and explanatory advantages of extending the use of the concept in this way. Finally, narcissism can be employed at the level of macroculture to describe a persistent theme in human history symptomized by such phenomena as slavery and nationalism (Fine, 1986) or to describe the egocentrism, individualism, and superficiality of western capitalist society (Lasch, 1978, 1984; see also, Cooper, 1986; Gendlin, 1987; Richards, 1989). These applications of the narcissism concept at the societal level, though often unsystematic, are provocative, and they provide much of the inspiration for this article. IDENTITYAND LEVELSOF ANALYSIS Application of the narcissism concept to groups and organizations rarely has been attempted (Kets de Vries, 1996; Schwartz, 1987a,b,c,

1997

Brown

649

1990a,b). Part of the reason for this may be scholars' uncertainty about how to apply a psychoanalytic concept at the organization or group level without reification. The essential problem is to make meaningful notions of collective needs for self-esteem and collective efforts at self-esteem regulation. At an individual level the motivation to preserve and increase self-esteem is tied to the self-concept, but it is not immediately clear what might be meant by an organizational need for self-esteem. Scholars can use at least two strategies for dealing with this issue: (1) they can consider narcissism as a metaphor for understanding collective behavior, and (2) they can define organizations cognitively as existing in the social identities of their participants. The first possibility involves understanding the narcissistic personality described above as an image that can be employed as a metaphor for understanding organized behavior. A number of scholars have suggested that metaphors are a "basic structural form of experience through which human beings engage, organize and understand their world," creating meaning by helping us understand one phenomenon through another (Morgan, 1983: 601; see also Jakobson, 1962; Jakobson & Halle, 1956; Lacan, 1966; Morgan, 1980, 1986; Ortony, 1975; Palmer & Dunford, 1996). Indeed, the argument made here has, to an extent, been prefigured by Staw, who argues that "micro [psychological] theory can serve as a useful metaphor for organization-level theory" (1991: 811). Viewed from this perspective, groups and organizations are not literally narcissistic entities, but they behave in ways that are, in certain important respects, analogous to the behavior exhibited by narcissistic individuals. Understanding narcissism as a metaphor effectively absolves us from having to locate an actual organizational need for self-esteem. Just as we can argue that organizations have machine-like qualities without suggesting that they have all the properties of machines, or have organismic properties without implying that they are actually alive, so we can borrow some of the language associated with the theory of narcissism and selectively apply those concepts that aid us in gaining an understanding of our target domain (Tsoukas, 1991, 1993). Although the concept and theory of narcissism reasonably can be applied metaphorically, I do not, as a matter of fact, pursue this line of reasoning in this article. Instead, I argue that collective entities, in the form of groups and organizations, literally have needs for self-esteem that are regulated narcissistically. Based on the work of Tajfel and Turner and their colleagues (see Tajfel, 1972;Tajfel & Turner, 1986;Turner, 1985;Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987; Turner & Oakes, 1989), I argue here that organizations consist in the common social identification of participating individuals, that the phrase "organizational behavior" refers to the behavior of individuals acting as their organization, and that organizational self-esteem consists of the collective self-esteem of individuals acting as the organization. At the level of the individual, the self-concept may be conceived of as a cognitive structure consisting of a set of concepts subjectively

650

Academy of Management

Review

July

available to a person in attempting to define him/herself (Gecas, 1982; Gergen, 1971; Hogg & Abrams, 1988; Knorr-Cetina, 1981; Markus & Wurf, 1987; Schlenker, 1985; Weick, 1995). This structure consists of two subcomponents: (1) personal identity, which refers to person-specific attributes, and (2) social identity, which refers to social group memberships. Organizations and their component subgroups play an important role in helping to confer social identity by offering images (concepts) with which their participants may identify (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Douglas, 1987; Dutton, Dukerich, & Harquail, 1994; Kramer, 1991). Identification is a key concept here, for it refers to a perception of oneness with or belongingness to a social category. The "strength of a member's organizational identification reflects the degree to which the content of the member's self-concept is tied to his or her organizational membership" (Dutton et al., 1994: 242; see also Gonzalez, 1996, and Katz & Kahn, 1966: 345-346). Furthermore, different elements of the self-concept (called self-images) dominate cognition and behavior at different times, with the saliency of a given self-image being a function of relative accessibility and fit (Turner, 1987). The important implications of this theory are twofold. First, organizations and their subgroups are social categories and, in psychological terms, exist in the participants' common awareness of their membership. In an important sense, therefore, organizations exist in the minds of their members, organizational identities are parts of their individual members' identities, and organizational needs and behaviors are the collective needs and behaviors of their members acting under the influence of their organizational self-images. This argument may be regarded as a clarification of Chatman, Bell, and Staw's contention that the identity of organizations is manifested in the actions of individuals who act "as the organization" when they embody the values, beliefs, and goals of the collectivity (1986: 211; see also Wegner, 1987, and Weick & Roberts, 1993). Second, we can now clearly distinguish between individual and collective levels of self-esteem. An individual who is motivated to preserve and enhance his/her self-image based entirely or primarily on personal identity is operating as a unique person. In this instance the need for selfesteem is unambiguously located at the level of the individual. An individual who is motivated to preserve and enhance his/her self-image based entirely or primarily on social identity is operating as a representative of a social category. Here, the individual is, in a sense, behaving as that social category, and his/her individual need for self-esteem is also identifiable as the social category's need for self-esteem. When all or most members of a social category are motivated to preserve and enhance their self-images based entirely or primarily on that social category, then the sum of their individual needs for self-esteem represent the collective need for self-esteem of that social category. Thus, there is a "continuous reciprocal interaction and functional interdependence between the psychological processes of individuals and their activity, relations and products" (Turner, 1987: 205-206) as groups and organizations. Individuals and

1997

Brown

651

the social categories they participate in are "mutual preconditions," and "simultaneously emergent properties" of each other (Turner, 1987: 205-206).

IN ORGANIZATIONS NARCISSISM

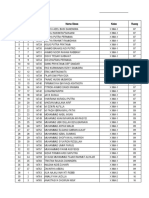

If it is true that groups and organizations have collective needs for self-esteem that are regulated narcissistically, it should be possible to discern the ego-defensive behaviors noted above in the extant organization studies literature. The importance of self-esteem in an organizational context was popularized initially by Maslow (1954), who tackled the concept explicitly, and by Festinger (1954), in whose theory of social comparison processes it is implicit (see also Heynes, 1950, and Van Zelst, 1951). For very many authors, self-esteem is an important theme or organizing principle structuring organizational life. Blau (1955), for example, describes how individuals who are socially integrated, secure, and derive satisfaction from their work tend to exert greater effort. In the work of Zaleznik (1966), participants struggle to maintain a sense of self in a context where their esteem is constantly under threat from status and competition anxiety, as well as fear of authority and uncertainty. For Katz and Kahn, the reward for participation in organizations is the establishment of self-identity and the expression of "values appropriate to this self-concept" (1966: 346). Terkel describes his book about work as "a search ... for daily meaning" in which people attempt to "maintain a sense of self" (1972: xiii, xviii). For Berger, "the socially established nomos" is "a shield against terror" (1973: 31-32). In Barley's (1986) study of CAT scanners, the importance of self-esteem maintenance is suggested by his description of the actions taken by individuals to manage their anxieties. More recently, Watson (1994) has argued that managers are perennially seeking to maintain their concept of self and to maintain their often fragile self-esteem (see also Baumeister, 1986; Brockner, 1988; Douglas, 1987; Harvey, Weber, & Orbuch, 1990; Lasch, 1978). However, recognition of the importance of self-esteem in organization studies has not led to a focus on collective ego-defensive behaviors. These behaviors are, though, detectable as implicit themes in the literature (see Table 1 for a summary).

Denial

Denial is an unconsciously deployed means of coping with what would otherwise be intolerable conflict, anxiety, and emotional distress (Laughlin, 1970: 57). The denial theme figures prominently in accounts of self-presentation (Abrahamson & Park, 1994; Elsbach, 1994; Niskala & Pretes, 1995; Wiseman, 1982) and in myth making (Alvesson & Berg, 1992; Boje, Fedor, & Rowland, 1982; Filby & Willmott, 1988; Gabriel, 1991; Morgan, 1986; Pettigrew, 1979; Schwartz, 1987b). These pieces are dominated by agency theories, assuming intentionality on the part of individuals, who are depicted as engaging in denial in their attempts to maximize

652

Academy of Management

Review

July

4.1

:s

06 I

4.1

<

0

U

0

a) 0 co a) $: M tl4 0.6 O

-4 00 6

Cq

4

:s

06I 0 CZ 0 0 :s rn rn

co

>

-

tlCO a)

U M lot

#-.4

0

U

O W

U

> 0

co

4.1 0 0 rM -0

0

4.1 U

016

0 U M ., co

4.1

0

-I....4

U 0

co

co

U)

X

U

0

--4

Uj 0

>4 co

--4 x

O

0

U -4 1-1

a)

)..4 0

0 :s I.= 0

N C-

CO U -g

0

0 Cn E-4

U

W W a)

Cj

U") (n

O

0 :IZ >

-I--,

--4

0

4.1

-1- -4 U

--4

a)

(n

a)

0 0

U)

O 4.1 N

O'd a) Z

U)

01

0 0

C,

co CT)

0

0

O ."

0

O

0

4.1 00

C-,)

rn

0)

0,

O

-O-,

>

(>I,) 0

>,

CD

CT)

0)

UO

_-z

Ui

CT) 00

0 --4 --4 CT) 0

(n

-I..,

4.1

CT

>4

-4 Cn

_4

--4

(n

U

Uj

--4 0 --4 -

-4

0

En

En 0

.P.4

4.1 4.1 0

U -4 0)

>

4.1 -4

>

U

00 a)

00 4.1

(n OC) Cr) (1)

00

-4

93

-#4

N

:s 0 CT)

'a)

4.1

(n

4.1 0

(n

(n

0 U 0 -4

Mx U O 0

0

00

__Z Cq CT)

>

tm

(1) U ja, Cn 0,

Cq

0

(n 0

-4-

1-4

O O

C,)

$: .- .- 5 O

>

C --4 r. 4

>4

(1) (n

---4

N 0Z --4 Q 4.1

0

U Cr)

LO

U CT)

14-1 0 -"a) --4 :s

LC) Cr)

(n

4 O

C:6

--4

0 --4 --4

(n

U

LO

(n

(1) Q

.(n

:s V

O

-Q 00

(n

0 CT)

--4

--4

>4 4.1

0

U

0 CT) U LO

4.1

8)) 4.1 4.1 O 0

-4 U --4

>

Cr)

U 00

--4 00) (n

CT)

U

0 U

U 00

C" CT)

CT)

Cq U

CT) --4

0

U

U)

-.4

U)

U

U 0 -4 --4 O

00

-4-1

U 0 0

0 0

0)

0 0)

(n

--4 0 0 U 0

(n

(1)

CD 00

Cr) CT)

CD

(n

(n (n

(n CT) CT)

-.1 -4

LO

(n

Lr)

CT)

CT) (n

Ci U

0 >

00 CT)

U (1)

0

--4

U 0

(n

00

--4 CT)

4.1

00 CT)

C-,

06

0

0

0

--4

..4 > ...4

--4 > --4

U)

CT)

CT)

0 O (n

Cr)

0

4 U

En En En Cn

-4

0)

O --4 0 --4

0)

U)

1997

Brown

653

a)

O _

:,a)

0

U-

>

-: _ r~~~~~~~.10

o" =~~~~~~~~~'

r, o>

- u U o.o@X=o

0 -'A

LO

0

u

Cn

> a)

a)

Q On

a)3 00

>

U: --

::S

E

E , c.

_oO

COCT

a) |~

.

.

u V~~~~~~~~~~::

U ;

d4

4-

-I.a., o

- 6 , .>

C- v'

CD

; X

O O) 0-_

CT)

U)C

OC

4cr

<

<0 U~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~c) o

654

Academy of Management

Review

July

economic gain (Dutton & Dukerich, 1991; Elsbach, 1994). Although some of this activity almost certainly is conceived deliberately, the suggestion here is that participants also conceal/deny disagreeable truths from themselves as well as others in an unconscious and self-deceptive attempt to preserve self-esteem (Staw et al., 1983). At an individual level, the tendency of organizational leaders to deny the reality of market demands and resource constraints has received some attention (Conger, 1990; Sankowsky, 1995; Schwartz, 1987b). Goffman (1959) has identified organization members who self-deceptively hide or deny facts about themselves from themselves. The idea that individuals, acting as representatives of their organizations, deny fault and responsibility for problems also has been embraced explicitly by impression management researchers. The literature on self-presentation suggests that participants' have a sense of their organization's identity that they attempt to maintain, therefore influencing their choice of action (Dutton & Dukerich, 1991; Weick, 1988: 306); this literature also contends that participants are acutely sensitive to their organizations' external reputations, which they seek to preserve and enhance by means of the information they disclose (Caves & Porter, 1977; Dutton & Jackson, 1987; Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Fombrun & Zajac, 1987). In performing these activities, these people, as shown in abundant evidence, provide prejudiced explanations for occurrences (denying, concealing, and omitting) that attenuate personal and organizational responsibility for controversial events (Leary & Kowalski, 1990; Pfeffer, 1981; Schlenker, 1980; Schonbach, 1980). Consider, for example, Elsbach's (1994) study of the California cattle industry, which uncovered many instances of denial (in the form "we weren't involved" and "it didn't happen") engaged in by spokespersons in their efforts to separate their organizations from controversy. In their attempts to deny fault, corporate officers sometimes also will conceal negative organizational outcomes (Abrahamson & Park, 1994). A variety of case study material suggests that people suppress information (Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990: 180), hide negative financial data (Whetton, 1980: 162), conceal failure (Sutton & Callahan, 1987), and even "launch propaganda campaigns that deny the existence of crises" (Starbuck, Greve, & Hedberg, 1978: 118). This phenomenon has been documented at GM, where, despite considerable evidence of failings, executives refused to acknowledge "the truth about their corporate parent. They didn't want to believe" (Keller, 1989: 65, 66; see also Schwartz, 1990a,b). At the group level, denial has been elaborated by Janis (1972) under the label of "groupthink." The literature on myth making casts further light on the denial behavior of individuals, as well as groups and organizations (Alvesson & Berg, 1992; Boje et al., 1982; Brown, 1994; Filby & Willmott, 1988; Pettigrew, 1979; Schwartz, 1987a,b). Participants engage in myth making while attempting to make sense of things and events, and this "sensemaking occurs in the service of maintaining a consistent, positive self-conception" (Weick, 1995: 23; see also Steele, 1988). Myths help

1997

Brown

655

define "truth" and "rationality," while "glossing over excessive complexity, turbulence, or ambiguity" (Boje et al., 1982); they function as "patterning devices" that cohere and give order to participants' understandings (Alvesson & Berg, 1992); and they establish what ideas and behaviors are unacceptable and what is legitimate (Pettigrew, 1979: 576; see also Abravanel, 1983; Barthes, 1972; Burrell & Morgan, 1979; Cohen, 1969; Trice & Beyer, 1985). In doing so, myths sometimes overtly deny that something is the case; often conceal conflicting or contradictory information; and, because of their exclusivity, always omit other equally valid interpretations and evaluations. Myths, then, are a vehicle for denying errors and responsibilities when self-esteem is threatened (Gabriel, 1991; Kets de Vries & Miller, 1985: 138). When shared, myths serve as collective wish fulfillments that cannot be negated by contrary evidence (Zaleznik, 1989), for they function as self-deceptions that assist in individuals' and groups' avoidance of reality (Gabriel, 1991; Schwartz, 1985). An example of this is Schwartz's (1987b) analysis of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, which portrays NASA as an organization whose participants denied there was a difference between their ideal organization and the actual NASA organization. This, in turn, led them to fantasize that, as members of NASA, they were incapable of failure-with catastrophic consequences. Perhaps the most thoroughly researched medium through which an organization denies its problems and responsibilities is the organization's annual report and its associated letters to shareholders (Bell, 1984; Graves, Flesher, & Jordan, 1996; Hager & Scheiber, 1990; Ingram & Frazier, 1983; Judd & Tims, 1991; Preston, Wright, & Young, 1996). These "kaleidoscopic, glamorous, and entertaining" documents (Graves et al., 1996: 59) seek to present memorable "facts," emphasizing the image the organization wishes to portray by means of sophisticated visual and textual strategies, while at the same time denying, omitting, and concealing information incompatible with such rhetoric (Bolton, 1989; Ewen, 1988;Lewis, 1984). The most blatant examples of denial by omission occur in the form of environmental disclosures, which are often incomplete and not related to the firm's actual environmental performance (Niskala & Pretes, 1995; Wiseman, 1982). Rationalization A rationalization is an attempt to develop plausible and acceptable justifications for motives or actions (which participants may feel are not credit worthy) in an attempt to maintain sense of self (Laughlin, 1970: 251). At the level of the individual in organizations, Zaleznik (1966: 31) comments on how executives immobilized by difficult problems tend to rationalize their inaction, using arguments ranging from their having inadequate authority to their subordinates providing too little, or confused, information. The idea that organization participants offer rationalizations for their past actions is implicit in Weick's (1979: 1995) concept of

656

Academy of Management

Review

July

retrospective sense making, which suggests that individuals offer explanations for their activities that preserve their self-esteem. Rationalization is also central to our understanding of how individuals redefine their past actions using arguments leading to their escalation of commitment (Staw, 1980). Pfeffer (1981) makes explicit use of the notion to refer to the tendency of organizational leaders to offer justifications for policies that fit the social context in which they are offered. For Pfeffer, rationalizations are linguistic devices that secure legitimacy for actions and that obfuscate inequitable resource distributions in ways that are both deceptive and self-deceptive. The concept has been dealt with most adequately by Janis (1989), who argues that policy makers are often more inclined to satisfy their own personal motives and emotional needs than the requirements of their organizations. The result is that decisions are made for egocentric reasons, which then must be justified/rationalized (often un-self-consciously) by means of "impressive-sounding reasons," which present "the new policy in terms of benefits to the organization" (Janis, 1989: 65). The significance of rationalization is suggested, for example, in Auletta's (1985a,b, 1986) accounts of the fall of the Lehman brothers and power and greed on Wall Street. These include a detailed description of Lewis L. Gluckman's ousting of his co chief executive officer, Peter G. Peterson, for self-serving motives that needed to be rationalized in order to be found acceptable both by Gluckman and the business community. Some scholars have recognized that rationalization can also be a feature of group behavior (Filby & Willmott, 1988; Janis, 1972; Laughlin, 1970; Pfeffer, 1981; Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). As Laughlin (1970: 627, 628) has made clear, social or collective rationalization involving the large scale, and shared development of rationalizations for motives and behavior, are features of national and geographical groups, classes of people, political parties, and large organizations. Pfeffer (1981) writes of "management" as a collective group offering rationalizations for structures and behaviors in order to maintain and enhance organizational legitimacy. For Janis (1972), rationalization is a psychological defense mechanism associated with the phenomenon of groupthink. In Filby and Willmott's (1988) analysis of a public relations department, the public relations specialists are depicted as rationalizing their low status through myth and humor. This case study is particularly interesting, for it illustrates that although rationalization can help a group manage its sense of self-esteem, it can do so in ways that are self-defeating. At the organization level, the pervasiveness of rationalization is hinted at by Douglas in her description of how institutions "create shadowed places in which nothing can be seen and no questions asked," whereas "other areas show finely discriminated detail" (1987: 69). Her argument is that the social order of institutions establishes "selective principles" (rationalizations) that highlight and obscure events, control memory, provide categories for thought, set the terms for self-knowledge, and fix identities. This phenomenon has been commented on directly by

1997

Brown

657

Starbuck (1983), who notes that organizations act unreflectively and nonadaptively most of the time. However, because of strong societal demands for rationality, organizations retrospectively seek out and label events as problems, threats, and opportunities, and they characterize their actions as logical responses to these needs. To support their accounts, organizations develop strong ideologies for rational problem-solving behavior, and these ideologies often are supported by ceremonies and selection devices. Starbuck's conclusion is that a large portion of what seems to be rational behavior actually consists of actions that are post hoc justified (rationalized) to the organization's employees and to managers themselves. Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter's (1956) case study of a sect that had predicted the end of the world at a specific time is an excellent example of organizational rationalization. As the time specified approached, the sect announced that the world had been spared as a result of its activities and that the sect had been charged with the responsibility of preaching this good news. Rather than confront the possibility of contradictory evidence, the sect offered a rationalization for its beliefs and behavior that preserved intact its self-concept and self-esteem. More recently, Dutton and Dukerich have shown how the New York Port Authority rationalized its initial decision not to respond to the issue of homelessness on the grounds that it "lacked the social service skills necessary" (1991: 545). Interestingly, the decision to treat homelessness as a moral rather than a business issue later was reversed; drop-in centers, which became "a source of pride" for employees, were opened; and the earlier line of reasoning was overtly exposed as a defensive rationalization. In Ross and Staw's (1993) account of the construction of the Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant, the authors illustrate how the Long Island Lighting Company employed defensive rationalizations for its activities that were so inaccurate the company was indicted for fraud. Perhaps the best known example of organizational rationalization is GM's steadfast defense of the Corvair-despite the evidence of deaths, injuries, legal cases, and the company's own engineering records (Nader & Taylor, 1986; Wright, 1979). Self-Aggrandizement Self-aggrandizement refers to the tendency of an individual to overestimate his or her merits and accomplishments, which in the fantasy life of the narcissist is often accompanied by extreme self-absorption, exhibitionism, claims to uniqueness, and a sense of invulnerability (American Psychiatric Association, 1980, 1986). As explanations for the behavior of individuals in organizations, these traits have been commented on widely (Janis, 1989; Kets de Vries & Miller, 1985; Lasch, 1978; Watson, 1994; Zaleznik, 1966). Indeed, the ideas that leaders constantly engage in fantasies of omnipotence and control (Gabriel, 1991; Lasch, 1978; Zaleznik, 1966), often fall prey to grandiosity and exhibitionism (Kets de Vries &

658

Academy of Management

Review

July

Miller, 1985), and sometimes even seek "to create a culture cast in their own image, to perpetuate their own personal values and achieve an organizational form of immortality" (Martin, 1992: 8) are now well established. In its mildest form the enhancement of self-esteem through fantasies may be beneficial to the organization, as shown, for example, in Watson's description of those managers who spoke of "loving the people here" and enjoying the "buzz" of being in a position to direct events (1994: 70). Relatively mild self-aggrandizing behavior also is manifested by individuals in their narration of stories and myths-activities that are, per se, exhibitionistic and ego enhancing (Harvey et al., 1990: 13). In addition, the content of the stories and myths narrated provides additional opportunities for individuals to reaffirm their social identity, to illustrate their knowledge and prowess, to exert influence, and to offer explanations for events that flatter them and enhance self-esteem (Boje et al., 1982; Gabriel, 1991). More acute forms of self-aggrandizement are described in Janis's (1989) analysis of egocentric executives and in Lamb's (1987) account of "nonsensical acquisitions" in the 1980s, which he explains in terms of chief executives' needs for ego enhancement-especially their desire for excitement, power, and prestige (see also Conger, 1990, and Miller & Droge, 1986). Rituals also provide opportunities for individuals to build positive self-esteem. Consider, for example, the practice at General Motors Corporation of meeting visiting senior staff at the airport with a retinue proportional to their status-a ritual directly bolstering those individuals' self-esteem by fulfilling their needs for attention and allowing them to experience attitudes of superiority (Wright, 1979). The importance of self-aggrandizement as a motive for individual behavior is suggested as well in biographies and autobiographies of successful leaders. Sculley's (1987) immodest account of his exploits at Pepsi and Apple, and Royko's (1971) characterization of Mayor Daley of Chicago, provide interesting insights in this respect. Consider, for example, Royko's comment about the Mayor's retirement: "He'll settle for something simple, like maybe another jet airport built on a man-made island in the lake, and named after him, and maybe a statue outside the Civic Center, with a simple inscription, 'The greatest mayor in the history of the world.' And they might seal his office as a shrine" (1971: 17). Self-aggrandizement as a feature of group behavior also has been commented upon widely (Blau, 1955; Filby & Willmott, 1988; Janis, 1972; Schwartz, 1987c; Sculley, 1987). The tendency of groups to use myth and humor to exaggerate their sense of self-worth (Filby & Willmott, 1988), to fantasize of unlimited ability during times of stress (Janis, 1972), to engage in social cohesion ceremonies that are overtly exhibitionistic (Trice & Beyer, 1985, 1993), and to develop special languages and symbols that emphasize uniqueness (Blau, 1955) all have been researched thoroughly. These same themes are yet more evident in the literature on organizations. When Kluckhon suggests that culture is a "giant effort to mask life's

1997

Brown

659

fundamental insecurities" (1942: 66), and when Ferguson writes of conventions and institutions remaining "the objects of passionate adoration long after they have outlived their usefulness" (1936: 29), both are touching on aspects of self-aggrandizement in the social process of organizing. Perhaps the clearest statement of this in the organization literature is Douglas's contention: Institutions systematically direct individual memory and channel our perceptions into forms compatible with the relations they authorize. They fix processes that are essentially dynamic, they hide their influence, and they rouse their emotions to a standardized pitch on standardized issues. Add to all this that they endow themselves with rightness and send their mutual corroborationcascading through all the levels of our information system. No wonder they easily recruit us into joining their narcissistic self-contemplation. (1987:92) The literature on organizational uniqueness and organizational architecture provides particularly graphic examples of organizational aggrandizement. Organizations make claims to uniqueness through, among other things, stories (Martin et al., 1983; Selznick, 1957: 151), ceremonies (Ash, 1981; Rosen, 1985), rituals (Evered, 1983), myths (Schwartz, 1987a), the speeches of senior executives (Piccardo, Varchetta, & Zanarini (1990), annual reports (Preston et al., 1996; Salancik & Meindl, 1984), corporate logos (Hampden-Turner, 1990), and corporate histories (Rowlinson, 1987; Rowlinson & Hassard, 1994). These claims to uniqueness often emphasize the prowess and accomplishments of the organization in ways that are palpably exhibitionistic and exaggerated. There are many examples. For instance, at AT&T employees like to narrate the story of how they dealt with a major fire, which exaggerates their ability to cope with disasters (Kleinfield, 1981: 307). The visit of an admiral to a U.S. Navy ship is associated with an elaborate ritual, suggestive of exhibitionism and intense self-absorption (Evered, 1983: 134). In the United Kingdom, companies such as Cadbury and Fry deliberately have sought to carve out unique identities based on the religious ideals of their founders by commissioning corporate histories emphasizing that they are "special" and "imbued with a morality lacking in other firms" (Rowlinson, 1987: 86). The annual reports of many organizations tend to stress their individuality and achievements, often using color photographs and re-presenting information to send the "right message" (Bolton, 1989; Ewen, 1988; Howard, 1991; Lewis, 1984; Pettit, 1990; Preston et al., 1996; Salancik & Meindl, 1984). Self-aggrandizement is apparent as well in the architecture and office layouts that organizations deploy (Berg & Kreiner, 1990). The importance of corporate architecture and office design as an influence on behavior, an expression of corporate identity, and a symbol of status has been commented upon widely (Davis, 1984; Grafton-Small, 1985; Holm-Lofgren, 1980; Schwantzer, 1986; Seiler, 1984). It is apparent that organizations

660

Academy of Management

Review

July

spend vast amounts of resources on stylish buildings, office layouts, and landscaped gardens in an attempt to express their uniqueness and, inadvertently, their vanity. These intentional manipulations of physical space are palpable claims to superiority, often designed to communicate a sense of invulnerability and to excite admiration. One of the most vivid accounts of the narcissistic displays engaged in by organizations and their impact on self-esteem has been provided by Sculley's description of the PepsiCo boardroom: Like nearly everything else at PepsiCo Inc., the room's stately power and elegance made you stand a little straighter. A large abstract painting by Jackson Pollock's widow, Lee Krasner, dominated the far wall. Custom-designed carpeting in earthtone colors cushioned the floor. The bronze-plated ceiling, perhaps more appropriate for a church, reflected burnished mahogany-paneled walls. High-backed beige leather chairs, so imposing they could have carried corporate titles of their own, surrounded the boardroom table. (1987:1) Attributional Egotism Attributional egotism refers to the phenomenon wherein agents offer self-serving explanations for events, attributing favorable outcomes to their own efforts and unfavorable outcomes to external factors (Bradley, 1978; Miller & Ross, 1975; Schlenker, 1980; Snyder, Stephan, & Rosenfield, 1978; Staw, 1980; Zuckerman, 1979). As an explanation for the behavior of individuals in organizations, the concept of attributional egotism has attracted considerable attention (Abrahamson & Park, 1994; Erez & Earley, 1993; Kets de Vries & Miller, 1985; Martin et al., 1983; Ross and Staw, 1993; Schwartz, 1987a; Weiner et al., 1971). Zaleznik suggests that there is a tendency for executives "to blame external authority for personal plight and deprivation" (1966: 143). Abrahamson and Park (1994) suggest it as one possible explanation for corporate concealment. Schwartz (1987a) suggests a role for this form of self-enhancement bias in his discussion of the psychodynamics of totalitarianism. For Martin et al. (1983: 449), organizational stories provide a vehicle for self-enhancing explanations, which preserve individual reputations and self-esteem. One particularly detailed account of the importance of attributional egotism in organizations is contained in Ross and Staw's (1993) analysis of the Long Island Lighting Company's decision to build and operate the Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant. Their case study suggests "that decision makers saw the failing decision not so much a product of their own faulty calculus or lack of management as the result of intervention by external regulators and 'antisocial elements'" (Ross & Staw, 1993: 717). The attributional egotism concept also has been used widely to explain the behavior of collectivities, most usually through analyses of annual reports (Bettman & Weitz, 1983; Bowman, 1976; Ingram & Frazier, 1983; Salancik & Meindl, 1984; Staw et al., 1983). As long ago as 1976, Bowman found that the annual reports of food-processing companies for underper-

1997

Brown

661

forming organizations tended to blame unfavorable conditions and government regulations for their problems. Ingram and Frazier's research on the annual reports of organizations in the metals and chemicals industries concluded that "management attributes good performance to itself and poor performance to external factors" (1983: 59). The three largest scale surveys of this type (Bettman & Weitz, 1983; Salancik & Meindl, 1984; Staw et al., 1983) also reach similar conclusions. Although scholars agree that this phenomenon at the collective level exists, some contest the egodefensive explanation. For example, Miller and Ross (1975) argue that self-serving attributions are due to informational processing effects (Erez & Earley, 1993; Kunda, 1987). In this article I follow recent research, which suggests that individuals operating in groups and organizations are and selfprone to egotistic attribution for both information-processing concept-preservation reasons (Bettman & Weitz, 1983; Riess, Rosenfield, Melburg, & Tedeschi, 1981; Staw et al., 1983). I note, however, that central to the argument pursued here is the opportunity that attributional egotism offers for defending and enhancing self-esteem. Sense of Entitlement The narcissist's sense of entitlement (to success, power, and acclaim, for instance) often is accompanied by a tendency toward exploitiveness and a lack of empathy with the feelings of others, which manifests itself in interpersonal relationships that overtly lack depth (Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995; 1, 2). Various studies of the behavior of individuals in organizations suggest that these traits can be commonly observed (Jennings, 1971; Kets de Vries & Miller, 1985; Lasch, 1978; Macoby, 1976; Sankowsky, 1995). Indeed, there is some research to suggest that a sense of entitlement expressed in the form of self-confidence makes people more persuasive and thus better able to fulfill a leadership role (Kipnis & Lane, 1962; Mowday, 1979). According to Lasch, the prevalence of these behaviors is stimulated by "bureaucratic institutions, which put a premium on the manipulation of interpersonal relations, [and] discourage the formation of deep personal attachments" (1978: 44). In a similar vein, Macoby (1976: 107) suggests that the corporate "gamesman" has little capacity for personal intimacy and commitment and minimal loyalty, even to the company for which he/she works. In Kets de Vries and Miller's analysis of different types of narcissistic leader, a category of individuals is identified who "live under the illusion that they are entitled to be served" and who care "little about hurting and exploiting others in the pursuit of [their] own advancement" (1985: 588, 596). One example of this phenomenon is Abrahamson and Park's (1994) finding that, when circumstances permit, corporate officers express their sense of entitlement (in this case to financial rewards) by favoring their own interests over those of shareholders. Perhaps the best exemplifications of individuals' sense of entitlement and lack of empathy in an organization setting are contained in the biographies and autobiographies of those organizational leaders who have

662

Academy of Management

Review

July

been deemed or consider themselves successful (Harvey-Jones, 1988; Royko, 1971; Sculley, 1987). These themes are addressed explicitly more rarely at either the group or organizational level, although evidence for their pervasiveness is to be found across a wide range of literature. For example, in his study of a federal enforcement agency, Blau (1955: 167) describes a social cohesion ceremony in which one group, "Agents," sang a song that expressed a sense of entitlement to promotion. In Blau's (1955: 110, 111) other case study of a state employment agency, he illustrates how a group used humor, mostly involving the ridiculing of clients' accents, names, and clothes, in ways that evidenced an inability to empathize with their feelings. Rosen's (1985) analysis of an annual breakfast at the Spiro advertising agency provides further insight into exploitiveness at the level of the collectivity. Here, Rosen describes senior executives' speeches that portrayed the agency as providing generous rewards for its employees at a time when base salaries were lower than those paid by comparable agencies in the area and when salary increases were being delayed deliberately. The ideas that modern bureaucratic organizations are structured according to a principle of entitlement to exploit and that many shareholders and their professional managers adopt exploitative attitudes toward their workforce and the external environment are well explored (Callahan, 1962; Lasch, 1978; Marglin, 1974a,b). The connection between industrial capitalism and ruthless exploitation has been expressed famously in Frederick Taylor's phrase that the working man is no more than "a man of the type of an ox" (cited in Callahan, 1962). Lasch argues that modern capitalist production arose not for efficiency reasons but "because it provided capitalists with greater profits and power" (1978: 62). Marglin (1974a,b) suggests that the case for the factory system rested not on its technological superiority over handicraft production but on the more effective control of the labor force it allowed the employer. In Meyer and Rowan's (1977) analysis, organizations are depicted as assuming a sense of their own entitlement to continued successful existence, attempting to mold their institutional environments, artificially creating needs for their products, and seeking official protection. The potential consequences of these exploitative attitudes for employees also has received some attention. Beynon, for example, describes the Ford assembly line as "regulated tedium," and even "bondage," and the workers as "condemned" to carry out their work, which itself "traps," "brutalizes," and engenders "a terrible sense of isolation" (1973, 1984; see also Terkel, 1972). Anxiety The narcissistic personality is characterized by a sense of anxiety, which stems from a dependence on others to validate self-esteem. Analyses of the behavior of individuals in organizations strongly suggest that anxiety is a major feature of participants' lives (Berger, 1973; Kets de Vries, 1980; Kets de Vries & Miller, 1985; Schweiger & Denisi, 1991; Watson, 1994;

1997

Brown

663

Weick, 1995; Zaleznik, 1966). Many commentators have described the "internal suffering" of executives (Lasch, 1978: 44) and their need for stability and certainty to stave off anxiety (Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1991; Weick, 1995). Kets de Vries and Miller have identified those organizational leaders who experience "a sense of deprivation and emptiness" and "show a hypersensitivity to criticism, extreme insecurity, and a strong need to be loved" (1985: 588, 597). Zaleznik paints a picture of executives paralyzed by fear, whose esteem is constantly under threat, and who resort to fantasy and ritual in order to detach themselves "from personal anxiety and tension" (1966: 136). In his ethnography of a U.K. manufacturing company, Watson (1994) describes managers who are desperately attempting to maintain their fragile self-esteem in a difficult and chaotic world. A wealth of other studies link the prevalence of anxiety to dysfunctional outcomes, such as stress, job dissatisfaction, low trust and commitment, and intentions to leave the organization (Ashford, Lee, & Bobko, 1989; Bastien, 1987; Buono, Bowditch, & Lewis, 1985; Gil & Foulder, 1978; Marks & Mirvis, 1983; Schweiger & Denisi, 1991; Shirley, 1973; Sinetar, 1981). The salience of group anxiety in organizations has been illustrated by Menzies' (1970) research on nurses and Miller and Gwynnes' (1972) study of the social defense mechanisms at work in residential institutions. Menzies' (1970) study shows that nurses are subject to extremely high levels of tension, distress, and anxiety, which they seek to overcome through, for example, ritual task performance and denial of feelings of attachment. Miller and Gwynne's (1972) research suggests that residential institutions for the physically handicapped and young chronically sick are massively anxiety provoking for both staff and patients. These themes also figure prominently in the literature on organizations. Jacques (1955), for example, has contended that within the life of an organization, the defense against anxiety is one of the primary elements binding the individuals together (see also De Board, 1978). Anxiety and fear of loss of self-esteem are embraced either implicitly or explicitly by the Durkheimian concept of anomie, Marx's (1964) notion of alienation, and Gabriel's (1991) description of organizational myths as collective wish-fulfillment mechanisms. Durkheim's influence on theorists of organization has been especially important (Starkey, 1992). For Durkheim, "anomie" refers to a collective loss of self-esteem, which can "be remedied by providing the individual with a moral awareness of the social importance of his particular role" (Giddens, 1971: 230). Durkheim's (1912) emphasis on the "pathological" (anomic) state of organizations that results from the division of labor has been "reconceptualized as a psychological syndrome produced by the imbalance between technical and social needs within the organization of modern industry" by writers in the human relations tradition (Reed, 1985: 16). These theorists have responded to a perceived need for security and self-esteem by arguing, for example, for the creation of a shared moral order (Hill, 1981: 90), a sense of common purpose and cooperative relationships (Barnard, 1938), leadership attempts to secure

664

Academy of Management

Review

July

commitment (Selznick, 1957), and the broader distribution of work responsibilities (Walton, 1985). To summarize, participants in groups and organizations act individually, to preserve and enhance their personal identities, and collectively, to maintain their social identities. These behaviors involve the narcissistic regulation of self-esteem, and they take the form of the ego defensesdenial, rationalization, attributional egotism, ego aggrandizement, and sense of entitlement-which stave off anxiety. A largely implicit theme in the above review is that some groups and organizations will be more successful than others in regulating the self-esteem of their participants. This idea is central to our consideration of legitimacy. NARCISSISM AND LEGITIMACY The idea that the self-esteem of individuals is regulated partly through their participation in groups and organizations throws new light on the dynamics by which collectivities gain and maintain internal legitimacy. Because participants are involved in a reciprocal identity relationship with the groups and organizations in which they participate, they exhibit a normative acceptance of the rightness of these entities to exist. In other words, organizations offer individuals and groups the opportunity to share in the means by which their self-esteem may be continuously recreated and sustained in ways that make it motivationally compelling for them to accept their organization as desirable, proper, and appropriate-that is, as legitimate. This understanding of legitimacy is not at variance with conventional accounts of why legitimacy attributions are made, although it does suggest that such explanations are incomplete. Traditional accounts of the reasons why members attribute legitimacy to their organizations tend to suggest that these reasons are: (1) based on rational calculations of self-interest (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975; Emerson, 1962; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978; Wood, 1991); (2) a detection of congruence between the members' notions of what is right and good and the consequences, procedures, structures, and personnel associated with the organization (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994; Parsons, 1960; Scott, 1977; Scott & Meyer, 1991); and (3) because the organization offers explanations and models that allow participants to reduce anxiety and provide meaningful explanations for their experiences (Scott, 1991; Suchman, 1995; Wuthnow, Hunter, Bergeson, & Kurzweil, 1984). These arguments suggest that the provision of rewards to participants, the construction of a morally acceptable image with which members can identify, and the offer of explanations that make working life seem meaningful are valuable in and of themselves. I argue that this exchange relationship view of legitimacy is most plausible if we assume that these rewards function by reinforcing self-esteem. The crux of the argument is that legitimacy attributions are mediated by identification processes. Identification refers to "the degree to which a

1997

Brown

665

member defines him- or herself by the same attributes that he or she believes define the organization" (Dutton, Dukerich, & Harquail, 1994: 239). Individuals identify with groups and organizations to the extent that they define these social category memberships as enhancing their self-esteem; indeed, they adjust their degree of identification with organizations and groups in order to maximize self-esteem (Brewer, 1991). Although the degree of individual identification with a social category usually has not been linked to the concept of legitimacy, it has been associated with the internalization of its goals, values, norms, and traits (Ashforth & Mael, 1989); with the degree of commitment (Mowday, Porter, & Steers, 1982); with displays of cohesion, cooperation, and altruism toward other members of the organization (Billig & Tajfel, 1973);and with the diminished likelihood of absenteeism and psychological withdrawal from the organization (Tsui, Egan, & O'Reilly, 1992). Part of the reason why the connection with legitimacy usually has not been made is that whereas identification is a psychological concept, legitimacy principally is a concern of sociologists. Notable exceptions in this respect are Tajfel and Turner and their associates (Tajfel, 1972; Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner, 1985; Turner et al., 1987; Turner & Oakes, 1989), on whose work this article draws substantially. My argument is that the degree of identification between an individual and a social category will depend crucially on the collective regulation of individuals' self-esteem through the narcissistic ego-defense processes reviewed above. Processes of denial, rationalization, attributional egotism, self-aggrandizement, and sense of entitlement are not just identity maintaining but legitimacy enhancing. In acknowledging the legitimacy of the groups and organizations with which they identify, individuals are tacitly reaffirming their sense of self. Seen in the context of this argument, the pragmatic, moral, and cognitive rewards offered by social categories to their participants are the means by which individual and collective self-esteem are reinforced narcissistically. These rewards are, in short, the vehicles through which the legitimacy/self-esteem exchange relationship is transacted. Pragmatic rewards encourage positive self-esteem directly, by promoting selfaggrandizement and sense of entitlement, and indirectly, by allowing individuals to deny their faults, rationalize their actions, and attribute success to their own efforts. For example, rewards in the form of higher salaries or increased influence are self-aggrandizing for recipients, who are thus encouraged to think of themselves as unique and invulnerable. Over time, individuals can come to believe that they have a right, or sense of entitlement, to the rewards offered to them by groups and organizations. Continually receiving rewards allows individuals to deny their faults ("if I were not competent, I would not receive these rewards") and to engage in both rationalization ("my actions are justified by the rewards I receive") and attributional egotism ("success is due to me, and failure is the fault of other individuals or factors").

666

Academy of Management Review

July

Moral rewards, which an individual accrues as a result of a perceived correspondence between his/her morality and the several aspects of the organization, are similarly associated with positive self-esteem. These rewards encourage the individual to self-aggrandize ("because I am a member of a virtuous or worthwhile organization, I too am virtuous or worthwhile"), to deny moral improprieties and questioning of the individual's social utility ("since I participate in a good organization, my actions must be good"), to rationalize actions ("my actions are prompted by virtuous motives"), to possess a sense of entitlement ("the virtuous should receive"), and to engage in attributional egotism ("since I am good, so are the consequences of my actions"). Cognitive rewards bolster participants' self-esteem by offering models and conceptual frameworks that incorporate attributionally egotistic and rationalized explanations. These explanations often permit the denial of ignorance ("there is nothing important that I do not understand"). They also enhance a sense of entitlement ("I know that I am deserving") in the sense of overestimating one's and promote self-aggrandizement knowledge ("I understand my organization and my role in it"). I represent the interconnections among types of reward, ego defenses, self-esteem, identification, and legitimacy attributions in Figure 1. The figure makes it clear that although all organizations offer some rewards (to at least some of their participants) that engage their ego defenses, the degree to which they do this varies. In fact, I identify three basic categories of organization: (A) those in which the self-esteem of participants is adequately regulated, (B) those in which the self-esteem of participants is less than adequately regulated, and (C) those in which the self-esteem of participants is more than adequately regulated. The second and third categories are likely to be associated with pathological conditions, one symptom of which will be extremely low (in the former category) and high (in the latter category) levels of internal legitimacy. One may hypothesize that low levels of internal legitimacy will be associated with relatively low levels of participant loyalty and commitment and with high levels of staff turnover. Conversely, it seems reasonable to suggest that high levels of internal legitimacy will be associated with relatively high levels of participant loyalty and commitment and with low levels of staff turnover. Both extremes may well be associated with a relatively high incidence of organizational demise-in the former case because of paralysis brought about by anxiety and withdrawal, and in the latter case through too great an insulation from "reality." I pursue these themes in more detail in the next section, Implications for Research. The external projection of narcissism is also important for organizations, which must achieve legitimate status in their environments in order to secure resources and to avoid claims that they are negligent, irrational, or unnecessary (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975; Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Parsons, 1960). The idea that organizations must exhibit "congruence" (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975) or "isomorphism" (Meyer & Rowan, 1977) with the social

1997

Brown

667

E 2

o~~

0~~~~~~~~~~

o

0

._ -)

00 0

0 *

C

0Uo ,-

~~~~~~~~-o X0

.-

o N

*P

o%

c n

f

>

-r

n 0

C:

0U

o

o

~ ~~~~~~~Q

- o

-2

r

9c

39

U7

~

c

~

r

*~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~

Uo

U,

00

- o00

-:

o

g*

.

g s

-oo

U. o

~

0

~ ~ ~ ~~~~~C

0

T 0

0~~~~~~~~~~~~

0~~~~~

:3

668

Academy of Management

Review

July

values and norms of acceptable behavior in the larger social system is well established (Beyer, 1981; Sproull, 1981; Suchman, 1995). The argument that ours is a culture of narcissism characterized by ego aggrandizement, denial, rationalization, a sense of entitlement, and so on also has received some attention (Alvesson & Berg, 1992; Cooper, 1986; Gendlin, 1987; Lasch, 1978, 1984; Richards, 1989). That organizations are, in fact, required to incorporate and project narcissistic values and behaviors has not, however, been tackled explicitly by theorists of legitimacy, although it is a theme running through much written on the subject. Organizations generally seek to present an external "image" (Dutton & Dukerich, 1991) or "reputation" (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990) that is overtly narcissistic. Organizations are expected to be acutely sensitive to what outsiders think of them and to make the sort of strategic decisions and information disclosures that create a favorable impression (Caves & Porter, 1977; Dutton & Jackson, 1987; Fombrun & Zajac, 1987; Wilson, 1985). A favorable reputation can generate excess returns for a firm by inhibiting the mobility of rivals (Caves & Porter, 1977; Wilson, 1985), signaling product quality (Klein & Leffler, 1981; Milgrom & Roberts, 1986), attracting better applicants (Stigler, 1962), enhancing the firm's access to capital markets (Beatty & Ritter, 1986), and attracting investors (Milgrom & Roberts, 1986). Organizations are therefore encouraged to make optimistic projections about their performance, deemphasize the financial risks associated with holding their stock (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990), rationalize problems and errors (Staw, 1980), deny faults (Elsbach, 1994), and conceal negative information (Abrahamson & Park, 1994). Indeed, it may even be argued that the expression of narcissism through organizational architecture is "a purposeful adaptation to postmodern society with its emphasis on appearance and mass communication" and its insistence on individuality as a token of credibility (Berg & Kreiner, 1990: 43). In presenting a positive organizational identity, a firm's use of networks of interpersonal relations, corporate ties, press articles, and the mass media is key (Fombrun & Abrahamson, 1988; Mizruchi & Schwartz, 1987). Particularly notable is the role of advertising, which can help organizations develop strategic positions that "provide them with a measure of goodwill from consumers and other stakeholders" (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990: 241; see also Rumelt, 1987, and Weiss, 1969). Equally important are annual reports and letters to shareholders, through which organizations seek to represent themselves in ways that are both socially acceptable and often blatantly narcissistic (Graves et al., 1996; Hager & Scheiber, 1990; Preston et al., 1996). IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH In this article I have argued that organizations regulate the selfesteem of their participants through collective ego-defensive behaviors, with implications for identification and legitimation processes. This ar-

1997

Brown

669