Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Are Mobile Phones The 21 ST Century Addiction

Încărcat de

Irsa KhanTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Are Mobile Phones The 21 ST Century Addiction

Încărcat de

Irsa KhanDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

African Journal of Business Management Vol. 6(2), pp. 573-577, 18 January, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM DOI: 10.5897/AJBM11.

1940 ISSN 1993-8233 2012 Academic Journals

Full Length Research Paper

Are mobile phones the 21st century addiction?

Richard Shambare*, Robert Rugimbana and Takesure Zhowa

Tshwane University of Technology, South Africa.

Accepted 16 September, 2011

The mobile or cell phone has become the 21 century icon. It is ubiquitous in the modern world, as an on-the-go talking device, an internet portal, a social networking platform, a personal organizer, and even a mobile bank. In the information age, it has become an important social accessory. Since it is relatively easy to use, portable and affordable, its diffusion continues to surpass that of other ICTs. Research increasingly suggests cell phone usage to be addictive, compulsive and habitual. Students are among the heavy users of mobile technologies, and accordingly, a 33-item questionnaire measuring addictive and habitual behaviour was administered to a sample of students. Results indicate that indeed mobile phone usage is not only habit-forming, it is also addictive; possibly the biggest non-drug st addiction of the 21 century. Key words: Addiction, dependency behaviour, cell phones, mobile phones, youths.

st

INTRODUCTION As the popularity of ICT-driven communication increases, mobile phone usage has been tipped into mainstream culture. This is particularly true for young adults, who increasingly consider mobile phones as part of their being and identity (Hooper and Zhou, 2007; Madrid, 2003). Past studies demonstrate that young adults and students use cell phones for various purposes including Facebook, and students spend at least three hours every day on their Facebook accounts using mobile phones (Mvula and Shambare, 2011). Given the widespread adoption of mobile phones, many researchers have posited that their use is addictive, compulsive, dependent and habit-forming (Aoki and Downes, 2003; Hooper and Zhou, 2007; Madrid, 2003). Madrid (2003) particularly asserts that mobile phone usage is a compulsive and addictive disorder which looks set to become one of the biggest non-drug addictions in st the 21 century. Despite this, very little research attention has focused on this phenomenon, and even less has tested these claims empirically. It is against this background that the research reported on in this article investigated these claims by testing whether mobile phone usage is indeed addictive, compulsive and habitual. To achieve this, a mobile phone usage questionnaire developed by Hooper and Zhou (2007) to measure addictive, compulsive and habitual behaviour was tested on a sample of South African students. Since students usually take the lead in adopting technological innovations, including mobile phone usage (Rugimbana, 2007), a student population was considered ideal. Hooper and Zhou (2007) consider mobile phone usage as having a mobile phone and using it to communicate by means of calling or sending text messages commonly known as SMSs. For practical purposes, this definition was adopted for the purposes of this research. Mobile phone usage is a distinct consumer behaviour, the implications of which are potentially valuable to a multiplicity of disciplines including marketing and education. For educators, understanding how and why students use cell phones can provide them with knowledge not only to facilitate learning, but to discover means of embracing the technology in the classroom (Bicen and Cavus, 2010; Carter et al., 2008; Mvula and Shambare, 2011). On the other hand, marketers may gain valuable insight into using mobile phones as a medium for advertising as well as marketing mobile phones. Past research has identified numerous types of behaviour associated with mobile phone usage. Therefore, this study concerned itself with the identification of these

*Corresponding author. E-mail: shambarar@tut.ac.za.

574

Afr. J. Bus. Manage.

types of behaviour and the respective underlying motivations for that behaviour. In other words, the objectives of the research were to: 1. determine whether the types of behaviour, according to Hooper and Zhou (2007), are identifiable in the context of a developed nation such as South Africa 2. categorize mobile phone usage according to the typologies identified in the latter study, based on the underlying motivations The remaining sections of the paper are structured as follows: Firstly, the literature pertaining to mobile phone usage is reviewed in the following section. Secondly, the methodology employed to answer the research questions is presented. Results are then discussed. Finally, the paper concludes with implications of these findings, as well as suggested topics for future research.

technological advancement also guarantee mobile subscribers the freedom to use the Internet, email, social media such as Twitter and Facebook. Because of the wide array of features, mobile phones are ideal socialinteraction tools.

Dependency Following adoption, users become more comfortable using cell phones. Rogers (1995) identifies this as commitment to using an innovation. In other words, as adopters begin using mobile phones regularly they become part of the users lives to such an extent that the users feel lost without them (Hooper and Zhou, 2007).

Image and identity Mobile phones may also be considered as status symbols. In particular, Shambare and Mvula (2011) assert that South African students adopt mobile phones to use on Facebook, simply because their friends use cell phones for Facebook. Hence, Wilskas findings (2003) propose mobile phone usage as being addictive, trendy and impulsive.

LITERATURE REVIEW To appreciate mobile usage, the study considers a multidisciplinary review of the literature. Following on from Maslows motivation model, Hooper and Zhou (2007) posit that human behaviour can be viewed as the actual performance of behavioural intentions driven by certain underlying motives. This view appears to be consistent with adoption theories such as Ajzens theory of planned behaviour (1991) and Daviss technology acceptance model (1989). Basically, these models propose that product attributes (for example, relative advantage, perceived ease of use, or perceived usefulness) influence behavioural intention, which in turn initiates behaviour (Taylor and Todd, 1995). Motivation for mobile phone usage

Behaviour associated with mobile phone usage From these motives, the literature identifies six types of behaviour associated with mobile phone usage. These are habitual, addictive, mandatory, voluntary, dependent and compulsive behaviour (Hanley and Wilhelm, 1992; Hooper and Zhou, 2007; Madrid, 2003; OGuinn and Faber, 1989), and they are further discussed in detail.

Addictive behaviour Although mobile phones were initially used as communication devices, today, they are a 21st century icon that performs multiple roles (Garcia-Montes et al., 2006). Mobile phones can represent a bank if used in mobile banking (Jayamaha, 2008), a camera, personal organizer, a calculator and a social networking device (Bicen and Cavus, 2010). Aoki and Downes (2003) further argue that a mobile phone is no longer a phone linked to a space but rather a phone linked exclusively to an individual (Boyd and Ellison, 2008; Mvula and Shambare, 2011). Further, some of the more common motivations for mobile phone usage are discussed. Hanley and Wilhelm (1992) define addictive behaviour as any activity, substance, object, or behaviour that has become the major focus of a person's life to the exclusion of other activities, or that has begun to harm the individual or others physically, mentally, or socially. Addictive behaviours in general are a means of improving feelings of low self-esteem and powerlessness (OGuinn and Faber, 1989). In the context, therefore, increased attention, uncontrollable, and involuntary use of cell phones by subscribers can be regarded as an addiction.

Compulsive behaviour Social interaction Mobile phones are used for social interaction. Adopters use them to stay in touch with friends and family (Aoki and Downes, 2003). Improved mobile telephony and OGuinn and Faber (1989) argue that compulsive behaviour is behaviour that is repetitive that the concerned individual usually experiences a strong urge to continuously perform the behaviour. The behaviour is

Shambare et al.

575

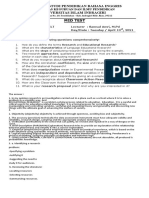

Table 1. Demographic profile.

Demographic characteristics Male Gender Female High school University diploma/degree Postgraduate One Two Three or more < 1 year 1 3 years 3 5 years 5+ years

Percent 29 71 42 26 32 64 28 8 7 15 10 68

Education level

Mobile phones owned

Mobile phone experience

typically very difficult to stop and ultimately results in harmful economic, psychological, or societal consequences.

officially required (Aoki and Downes, 2003), or parentally mandated. In terms of motivation, mandatory behaviour is usually driven or prompted by environmental consequences (Aoki and Downes, 2003). Research objectives

Dependent behaviour Dependent behaviour is different from addiction in that it is often motivated by the attached importance of a social norm (Hooper and Zhou, 2007). In this context, it is not addiction of mobile phone usage, but the attached importance of communication.

To achieve the research objectives, the following research question was formulated: RQ: What types of behaviour are associated with mobile phone usage?

RESEARCH DESIGN

Habitual behaviour Many behaviours that people perform regularly can be characterized as habits, since they are performed with little mental awareness (Biel et al., 2005). These are initiated by environmental cues in a given situation which call for individuals to act. The cues send signals to an established habit which corresponds to behaviour in a given situation.

A survey method was used to collect data from students in Pretoria, using non-probabilistic sampling methods (Kerlinger and Lee, 2000). Four undergraduate students, trained as research assistants, administered the instrument to participants.

Sampling and sample size The non-probabilistic sampling technique was utilized, and to ensure a more representative sample consisting of students at all study levels, both high school and university students were surveyed (Calder et al., 1981). While these two groups may appear to represent two separate populations, past studies (Livingstone, 2008) focusing on young consumers have tended to combine consumers under 35 years old as one population group. The choice for including the entire spectrum of students stems from the latter views. Research assistants were positioned at strategic locations, near schools and libraries, where they approached students to participate in the study. The demographic characteristics of the sample are illustrated in Table 1. A majority, some 71% of respondents were female. By education level, 42% were high school students, some 26% university students at undergraduate

Voluntary behaviour Unlike habitual and addictive behaviour, voluntary behaviour is reasoned behaviour which is driven by specific motivations. Mandatory behaviour Mandatory behaviour is defined as behaviour needing to be done, followed, or complied with, usually because it is

576

Afr. J. Bus. Manage.

Table 2. Three-factor solution of mobile usage responses.

Variable D5 M1 D1 D2 D3 D4 H3 H2 H1 H5 H4 A3 A2 C1 A1 A4 Eigenvalues Percentage of variance Cronbachs alpha ()

Factor 1 (Dependent) 0.840 0.803 0.783 0.781 0.765 0.754

Factor 2 (Habitual)

Factor 3 (Addictive)

0.828 0.762 0.722 0.712 0.695 0.751 0.737 0.726 0.633 0.598 6.954 26.065 0.915 2.214 18.209 0.832 1.713 16.181 0.788

Communalities 0.721 0.777 0.687 0.715 0.712 0.657 0.727 0.657 0.584 0.548 0.629 0.620 0.629 0.640 0.454 0.482 (Total) 60.455

level; the remaining 32% of participants were postgraduate students. A significant proportion (64%) owned one cell phone and about a quarter (28%) owned two cell phones. Some 8% indicated they owned and used three or more cell phones. Cell phone experience, as expected was very high, a vast majority of 68 per cent indicated that they had been using cell phones for at least five years. Respondents ages ranged from 14 to 38 years, yielding a mean age of age of 20.67 years with a standard deviation of 2.94 years. The K-S normality test was not significant (D = 1.279, p = 0.076), suggesting that the sample followed a normal distribution.

RESULTS This research question and the research objectives sought to identify the types of behaviour associated with mobile phone usage. It was also important to determine whether students exhibited one type of behaviour more than another or perhaps a set of behaviour types more than others. The MPUS was used to answer this question. Factor analysis was performed on the MPUS. According to Hooper and Zhou (2007), the MPUS contains six behaviour typologies, each represented by the six subscales: habitual, mandatory, dependent, addictive, compulsive and voluntary. These items are supposed to load independently in six factors or behaviour typologies. Tests to determine the suitability of factor analysis were all satisfactory (KMO = 0.831; Bartletts test of sphericity 2 = 845.195; df = 153; p < 0.000). Subsequently, factor analysis, with a principal component analysis (PCA) as an extraction method, was performed. As shown in Table 2, a three-factor solution explaining 60 per cent of variance was extracted. Factors were extracted on the basis of having eigen values greater than one. Dependency behaviour items loaded in Factor 1, habitual behaviour items loaded in Factor 2, and addictive behaviour items loaded in Factor 3. Table 2 illustrates that the three-factor solution accounts for at least 60% of the variance. Tests for internal consistency of items in all three factors yielded satisfactory results, as all factors

Data collection In total, 180 self-completion questionnaires were distributed to willing participants. Of these, 104 questionnaires were returned but only 93 were usable, representing a response rate of about 52%. The remaining 11 instruments had too many missing values to be useful.

Questionnaire To measure mobile phone usage patterns, Hooper and Zhous mobile phone usage scale (MPUS) (2007) was adapted and used to collect primary data. In keeping with the research objective of establishing whether cell phone usage is indeed addictive (Aoki and Downes, 2003; Madrid, 2003), the questionnaire used by Hooper and Zhou was considered most appropriate, as the latter study also considered a sample of students. A pilot test was conducted with 10 undergraduate students to ensure that the content of the questionnaire would be comprehensible to the target respondents (Dwivedi et al., 2006).

Shambare et al.

577

had Cronbachs alphas in excess of the 0.7 cut-off (Field, 2009).

DISCUSSION This research sought to establish the types of behaviour identifiable in mobile phone usage. A secondary objective was to assess how students in a resource-poor context compare to those in a resource-rich country. The researchers attempted to categorize mobile phone usage according to the typologies commonly identified in the literature. While earlier studies posit six typologies, this study found support for only three: dependency, habitual and addictive behaviour. These results suggest that mobile phone usage is dependency-forming, habitual and addictive. For instance, such dependent behaviour is exemplified by the overwhelming response to statements like: I often feel upset to think that I might be missing calls or messages. The reliability of each of the factors, namely dependency, habitual and addictive behaviour, was 0.915, 0.832 and 0.788, respectively. These are comparable to those found by Hooper and Zhou (2007), which were 0.842, 0.793 and 0.880, respectively. The high reliability loadings of these factors indicate that the three different types of behaviour are in themselves distinct constructs. Future research could consider looking at these constructs utilizing a different sample of mobile users.

REFERENCES Ajzen I (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process., (50): 179-211. Aoki K, Downes EJ (2003): An analysis of young peoples use of and attitudes toward cell phones, Telematics Inform., 20(4): 349-364. Biel A, Dahlstrand, U, Grankvist G (2005): Habitual and value-guided purchase behaviour, AMBIO, 34(4): 360. Boyd DM, Ellison NB (2008). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun., 13(1): 210-230. Carter HL, Foulger TS, Ewbank AD (2008). Have You Googled Your Teacher Lately? Teachers' Use of Social Networking Sites. The Phi Delta Kappan, 89(9): 681-685

Calder BJ, Phillips LW, Tybout AM (1981). Designing Research for Application. J. Consum. Res., 8(2): 197-207. Davis FD (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technol. MIS Q., 13(9): 319-339. Dwivedi YK, Choudrie V, Brinkman W (2006). Development of a survey instrument to examine consumer adoption of broadband. Ind. Manage. Data Syst., 106(5): 700-718. Field A (2009). Discovering Statistics using SPSS, 3rd Edition. Sage: Thousand Oaks, California. Garcia-Montes JM, Caballero-Munoz D, Perez-Alvarez M (2006). Changes in the self resulting from the use of mobile phones. Media Cult. Soc., 28(1): 67-82. Hanley A, Wilhelm MS (1992): Compulsive buying: an exploration into self-esteem and money attitudes. J. Econ. Psychol., 13: 5-18. Hooper V, Zhou Y (2007). Addictive, dependent, compulsive? A study of mobile phone usage. Conference Proceedings of the 20th Bled eConference eMergence: Merging and Emerging Technologies, Processes, and Institutions held in Bled, Slovenia, June 4 6. Jayamaha R (2008). The Impact of IT in the Banking Sector. Colombo. Kerlinger FN, Lee HB (2000). Foundations of Behavioral Research, 4th ed. Sydney. Harcourt College Publishers. Livingstone S (2008). Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: teenagers use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media Soc., 10(3): 393-411 Madrid A (2003): Mobile phones becoming a major addiction [Online]. Available from: http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/12/10/1070732250532.html?fro m=storyrhs Mvula A, Shambare R (2011). Students perceptions of facebook as an instructional medium. 13th Annual GBATA Conference Proceddings, Istanbul, Turkey O'Guinn TC, Faber RJ (1989): Compulsive Buying: A Phenomenological Exploration. J. Consum. Res., 16(2): 147. Rogers E (1995). Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press: New York. Rugimbana R (2007). Generation Y: How cultural values can be used to predict their choice of electronic financial services. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 11(4): 301-313. Taylor S, Todd P (1995). Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. Int. J. Res. Mark., 12: 137-155. Wilska TA (2003). Mobile phone use as part of young people's consumption styles. J. Consum. Policy, 26(4).

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- 54 - Z Score ExplainedDocument5 pagini54 - Z Score ExplainedIrsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perception of The Technical Drafting Students Towards Their Drafting ChairsDocument28 paginiPerception of The Technical Drafting Students Towards Their Drafting ChairsJamesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Proposal TemplateDocument8 paginiResearch Proposal TemplateKrishelle Ann BayaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Detailed Demonstration Lesson Plan FinalDocument6 paginiA Detailed Demonstration Lesson Plan FinalAriane Ignao LagaticÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cjhapter#1Document12 paginiCjhapter#1Irsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap 3Document41 paginiChap 3Irsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap#2Document11 paginiChap#2Irsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap#1Document7 paginiChap#1Irsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Members of European UnionDocument12 paginiMembers of European UnionIrsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Q1) Define Information System and Its ScopeDocument4 paginiQ1) Define Information System and Its ScopeIrsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship Report Al BarakaDocument38 paginiInternship Report Al BarakaIrsa Khan100% (2)

- Termenologies of Cost AccountingDocument2 paginiTermenologies of Cost AccountingIrsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Covering Letter DraftDocument2 paginiCovering Letter DraftIrsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- China-US Interest in Africa The Implications For Peace and DevelopmentDocument17 paginiChina-US Interest in Africa The Implications For Peace and DevelopmentIrsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Hybrid Method For Improving Forecasting Accuracy Utilizing Genetic AlgorithmDocument18 paginiA Hybrid Method For Improving Forecasting Accuracy Utilizing Genetic AlgorithmIrsa KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 - Assignment Number 3Document1 pagină3 - Assignment Number 3Sidra AfrasiabÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review EbayDocument4 paginiLiterature Review Ebayttdqgsbnd100% (1)

- Latest Social Science Reviewer Part 5Document7 paginiLatest Social Science Reviewer Part 5Maya Sin-ot ApaliasÎncă nu există evaluări

- PR2 NotesDocument9 paginiPR2 Notescali kÎncă nu există evaluări

- CICR08-13 - E&M Safety in Construction - RS - 014Document44 paginiCICR08-13 - E&M Safety in Construction - RS - 014Ahmed IdreesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3is WEEK 1 8 LUAY IMMERSIONDocument20 pagini3is WEEK 1 8 LUAY IMMERSIONCynthia LuayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Undertake Project Work-Case StudyDocument6 paginiUndertake Project Work-Case StudyMaria Tahreem100% (1)

- Assessing The Impact of Learning Activity Sheets On The Evaluation Skills of English 10 Students: A Case Study of "How My Brother Leon Brought Home A Wife"Document8 paginiAssessing The Impact of Learning Activity Sheets On The Evaluation Skills of English 10 Students: A Case Study of "How My Brother Leon Brought Home A Wife"Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 Understanding ResearchDocument23 paginiChapter 1 Understanding ResearchDimas Pratama PutraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Three Program EvaluationDocument5 paginiLesson Three Program EvaluationZellagui FerielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Job Mismatch in The Tourism and Hospitality Industry: A Phenomenological StudyDocument38 paginiEffect of Job Mismatch in The Tourism and Hospitality Industry: A Phenomenological StudyMarynette De Guzman PaderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Keerthi Kocherlakota - QMR IADocument6 paginiKeerthi Kocherlakota - QMR IAbinzidd007Încă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review On PotholesDocument6 paginiLiterature Review On Potholesjolowomykit2100% (1)

- Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris Universitas Islam Indragiri Mid TestDocument3 paginiProgram Studi Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris Universitas Islam Indragiri Mid TestRizky Nur AmaliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women'S Speech Styles Exemplified in The Speeches of Miriam Defensor SantiagoDocument67 paginiWomen'S Speech Styles Exemplified in The Speeches of Miriam Defensor SantiagoFeri AÎncă nu există evaluări

- Search For Seameo Young Scientists (Ssys)Document23 paginiSearch For Seameo Young Scientists (Ssys)Amanda WebbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Python Programming & Data Science Lab ManualDocument25 paginiPython Programming & Data Science Lab ManualSYEDAÎncă nu există evaluări

- 19-Article Text-23-1-10-20190326Document9 pagini19-Article Text-23-1-10-20190326taabaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Design: Memcha Loitongbam Professor MIMS, Manipur UniversityDocument75 paginiResearch Design: Memcha Loitongbam Professor MIMS, Manipur UniversityWolfie BoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Risk Management On Profitability of BankDocument5 paginiImpact of Risk Management On Profitability of Bankankit chauhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aqa Gcse History Coursework Mark SchemeDocument5 paginiAqa Gcse History Coursework Mark Schemef633f8cz100% (2)

- CRM in InsuranceDocument55 paginiCRM in InsuranceNitin SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper On Will SmithDocument7 paginiResearch Paper On Will Smithgz9avm26100% (1)

- Methods of Research Week 3-FDocument30 paginiMethods of Research Week 3-FShailah Leilene Arce BrionesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mlisc Anu PaperDocument8 paginiMlisc Anu PaperRavindra VarmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- College of Education Research Focus Areas 1 2020Document70 paginiCollege of Education Research Focus Areas 1 2020Kriben RaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neuroscience X CitiesDocument67 paginiNeuroscience X CitiesSergio Martty Ehecatl Orozco MejíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Level of Effectiveness of The Rehabilitation Programs Implemented in Angeles District Jail Female DormitoryDocument23 paginiThe Level of Effectiveness of The Rehabilitation Programs Implemented in Angeles District Jail Female DormitoryYoshito SamaÎncă nu există evaluări