Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Astorga vs. Peoplefacts

Încărcat de

Kuthe Ig TootsDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Astorga vs. Peoplefacts

Încărcat de

Kuthe Ig TootsDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

ASTORGA vs.

PEOPLEFacts: Private offended parties Elpidio Simon, Moises de la Cruz, WenefredoManiscan, Renato Militante,CrisantoPelias, SPO3 Andres B. Cinco, Kr. and SPO1 RufoCapoquian, members of DENR RegionalOperations Group, were sent to Western Samar to conduct possible illegal logging activities.Upon investigation of the group, Mayor Benito Astorga was found to be the owner of two (2)boats. A heated altercation ensued and Mayor Astorga called for reinforcements. Ten armed menarrived in the scene. The offended parties were then brought to Mayor Astogas house wherethey had dinner and drinks and left at 2:30am. SPO1 Capoquian further admitted that it wasraining during the time of their detention.Mayor Astorga was convicted of arbitrary detention by the Sandiganbayan. Issue: Whether Mayor Astorga is guilty of arbitrary detention. Held: No. The elements of arbitrary detention are as follows:1. That the offender is a public officer or employee.2. That he detains a person.3. That the detention is without legal ground.The determinative factor in arbitrary detention is fear. The Court found no proof that Astorgainstilled fear in the minds of the offended parties. There was also no actual restraint imposed onthe offended parties. The events that transpired created reasonable doubt and are capable of other interpretations. Mayor Astorga could have extended his hospitality and served dinner anddrinks to the offended parties. He could have advised them to stay in the island inasmuch as seatravel was rendered unsafe by the heavy rains. Astorga even ate and served alcoholic drinksduring dinner. The guilt of the accused has not been proven with moral certainty. Astorga wasacquitted

People Vs. Sy Chua Case Digest People Vs. Sy Chua 396 SCRA 657 G.R. No.136066-67 February 4, 2003 Facts: Accused-appellant Binad Sy Chua was charged with violation of Section 16, Article III of R.A. 6425, as amended by R.A. 7659, and for Illegal Possession of Ammunitions and Illegal Possession of Drugs in two separate Informations. SPO2 Nulud and PO2 Nunag received a report from their confidential informant that accusedappellant was about to deliver drugs that night at the Thunder Inn Hotel in Balibago, Angeles City. So, the PNP Chief formed a team of operatives. The group positioned themselves across McArthur Highway near Bali Hai Restaurant, fronting the hotel. The other group acted as their back up. Afterwards, their informer pointed to a car driven by accused-appellant which just arrived and parked near the entrance of the hotel. After accused-appellant alighted from the car carrying a sealed Zest-O juice box, SPO2 Nulud and PO2 Nunag hurriedly accosted him and introduced

themselves as police officers. As accused-appellant pulled out his wallet, a small transparent plastic bag with a crystalline substance protruded from his right back pocket. Forthwith, SPO2 Nulud subjected him to a body search which yielded twenty (20) pieces of live .22 caliber firearm bullets from his left back pocket. When SPO2 Nunag peeked into the contents of the Zest-O box, he saw that it contained a crystalline substance. SPO2 Nulud instantly confiscated the small transparent plastic bag, the Zest-O juice box, the twenty (20) pieces of .22 caliber firearm bullets and the car used by accused-appellant. SPO2 Nulud and the other police operatives who arrived at the scene brought the confiscated items to the office of Col. Guttierez at the PNP Headquarters in Camp Pepito, Angeles City. Accused-appellant vehemently denied the accusation against him and narrated a different version of the incident. Accused-appellant alleged that he was driving the car of his wife to follow her and his son to Manila. He felt sleepy, so he decided to take the old route along McArthur Highway. He stopped in front of a small store near Thunder Inn Hotel to buy cigarettes and candies. While at the store, he noticed a man approaches and examines the inside of his car. When he called the attention of the onlooker, the man immediately pulled out a .45 caliber gun and made him face his car with raised hands. The man later on identified himself as a policeman. During the course of the arrest, the policeman took out his wallet and instructed him to open his car. He refused, so the policeman took his car keys and proceeded to search his car. At this time, the police officers companions arrived at the scene in two cars. PO2 Nulud, who just arrived at the scene, pulled him away from his car in a nearby bank, while the others searched his car. Thereafter, he was brought to a police station and was held inside a bathroom for about fifteen minutes until Col. Guttierez arrived, who ordered his men to call the media. In the presence of reporters, Col. Guttierez opened the box and accused-appellant was made to hold the box while pictures were being taken. The lower court acquitted Sy Chua for the Illegal Possession of Ammunitions, yet convicted him for Illegal Possession of 1,955.815 grams of shabu. Hence, this appeal to the Court. Issue: Whether or Not the arrest of accused-appellant was lawful; and (2) WON the search of his person and the subsequent confiscation of shabu allegedly found on him were conducted in a lawful and valid manner. Held: The lower court believed that since the police received information that the accused will distribute illegal drugs that evening at the Thunder Inn Hotel and its vicinities. The police officer had to act quickly and there was no more time to secure a search warrant. The search is valid being akin to a stop and frisk. The trial court confused the concepts of a stop-and-frisk and of a search incidental to a lawful arrest. These two types of warrantless searches differ in terms of the requisite quantum of proof before they may be validly effected and in their allowable scope. In a search incidental to a lawful arrest, as the precedent arrest determines the validity of the incidental search, the legality of the arrest is questioned, e.g., whether an arrest was merely used as a pretext for conducting a search. In this instance, the law requires that there first be arrest before a search can be madethe process cannot be reversed. Accordingly, for this exception to apply, two elements must concur: (1) the person to be arrested must execute an overt act indicating that he has just committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to

commit a crime; and (2) such overt act is done in the presence or within the view of the arresting officer. We find the two aforementioned elements lacking in the case at bar. Accused-appellant did not act in a suspicious manner. For all intents and purposes, there was no overt manifestation that accused-appellant has just committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit a crime. Reliable information alone, absent any overt act indicative of a felonious enterprise in the presence and within the view of the arresting officers, is not sufficient to constitute probable cause that would justify an in flagrante delicto arrest. With regard to the concept of stop-and frisk: mere suspicion or a hunch will not validate a stop-and-frisk. A genuine reason must exist, in light of the police officers experience and surrounding conditions, to warrant the belief that the person detained has weapons concealed about him. Finally, a stop-and-frisk serves a two-fold interest: (1) the general interest of effective crime prevention and detection for purposes of investigating possible criminal behavior even without probable cause; and (2) the interest of safety and self-preservation which permit the police officer to take steps to assure himself that the person with whom he deals is not armed with a deadly weapon that could unexpectedly and fatally be used against the police officer. A stop-and-frisk was defined as the act of a police officer to stop a citizen on the street, interrogate him, and pat him for weapon(s) or contraband. It should also be emphasized that a search and seizure should precede the arrest for this principle to apply. The foregoing circumstances do not obtain in the case at bar. To reiterate, accused-appellant was first arrested before the search and seizure of the alleged illegal items found in his possession. The apprehending police operative failed to make any initial inquiry into accused-appellants business in the vicinity or the contents of the Zest-O juice box he was carrying. The apprehending police officers only introduced themselves when they already had custody of accused-appellant. In the case at bar, neither the in flagrante delicto nor the stop and frisk principles is applicable to justify the warrantless arrest and consequent search and seizure made by the police operatives on accused-appellant. Wherefore, accused-appellant Binad Sy Chua is hereby Acquitted

Lacson Vs. Perez Case Digest Lacson Vs. Perez 357 SCRA 756 G.R. No. 147780 May 10, 2001 Facts: President Macapagal-Arroyo declared a State of Rebellion (Proclamation No. 38) on May 1, 2001 as well as General Order No. 1 ordering the AFP and the PNP to suppress the rebellion in the NCR. Warrantless arrests of several alleged leaders and promoters of the rebellion were thereafter effected. Petitioner filed for prohibition, injunction, mandamus and habeas corpus with an application for the issuance of temporary restraining order and/or writ of preliminary injunction. Petitioners assail the declaration of Proc. No. 38 and the warrantless arrests allegedly effected by virtue thereof. Petitioners furthermore pray that the appropriate court, wherein the information against them were filed, would desist arraignment and trial until this instant petition is resolved. They also contend that they are allegedly faced with impending warrantless arrests and unlawful restraint being that hold departure orders were issued against them. Issue: Whether or Not Proclamation No. 38 is valid, along with the warrantless arrests and hold departure orders allegedly effected by the same. Held: President Macapagal-Arroyo ordered the lifting of Proc. No. 38 on May 6, 2006, accordingly the instant petition has been rendered moot and academic. Respondents have declared that the Justice Department and the police authorities intend to obtain regular warrants of arrests from the courts for all acts committed prior to and until May 1, 2001. Under Section 5, Rule 113 of the Rules of Court, authorities may only resort to warrantless arrests of persons suspected of rebellion in suppressing the rebellion if the circumstances so warrant, thus the warrantless arrests are not based on Proc. No. 38. Petitioners prayer for mandamus and prohibition is improper at this time because an individual warrantlessly arrested has adequate remedies in law: Rule 112 of the Rules of Court, providing for preliminary investigation, Article 125 of the Revised Penal Code, providing for the period in which a warrantlessly arrested person must be delivered to the proper judicial authorities, otherwise the officer responsible for such may be penalized for the delay of the same. If the detention should have no legal ground, the arresting officer can be charged with arbitrary detention, not prejudicial to claim of damages under Article 32 of the Civil Code. Petitioners were neither assailing the validity of the subject hold departure orders, nor were they expressing any intention to leave the country in the near future. To declare the hold departure orders null and void ab initio must be made in the proper proceedings initiated for that purpose. Petitioners prayer for relief regarding their alleged impending warrantless arrests is premature being that no complaints have been filed against them for any crime, furthermore, the writ of habeas corpus is uncalled for since its purpose is to relieve unlawful restraint which Petitioners are not subjected to. Petition is dismissed. Respondents, consistent and congruent with their undertaking earlier adverted to, together with their agents, representatives, and all persons acting in their behalf,

are hereby enjoined from arresting Petitioners without the required judicial warrants for all acts committed in relation to or in connection with the May 1, 2001 siege of Malacaang

Case Digest on BASCO vs. RAPATALO 269 SCRA 220 November 10, 2010 THE FACTS: An information for murder was filed against Morente. The accused Morente filed a petition for bail. The hearing for said petition was set for May 31, 1995 by petitioner but was not heard since the respondent Judge was then on leave. It was reset to June 8, 1995 but on said date, respondent Judge reset it to June 22, 1995. The hearing for June 22, 1995, however, did not materialize. Instead, the accused was arraigned and trial was set. Again, the petition for bail was not heard on said date as the prosecutions witnesses in connection with said petition were not notified. Another attempt was made to reset the hearing to July 17, 1995. Complainant allegedly saw the accused in Rosario, La Union on July 3, 1995 and later learned that the accused was out on bail despite the fact that the petition had not been heard at all. Upon investigation, complainant discovered that bail had been granted and a release order dated June 29, 1995was issued on the basis of a marginal note dated June 22, 1995, at the bottom of the bail petition by Assistant Prosecutor Oliva which stated: No objection: P80,000.00, signed and approved by the assistant prosecutor and eventually by respondent Judge. Note that there was already a release order dated June 29, 1995 on the basis of the marginal note of the Assistant Prosecutor dated June 22, 1995 when the hearing of the bail petition was aborted and instead arraignment took place) when another hearing was scheduled for July 17, 1995. Respondent Judge alleged that he granted the petition based on the prosecutors option not to oppose the petition as well as the latters recommendation setting the bailbond in the amount of P80,000.00. He averred that when the prosecution chose not to oppose the petition for bail, he had the discretion on whether to approve it or not. He further declared that when he approved the petition, he had a right to presume that the prosecutor knew what he was doing since he was more familiar with the case, having conducted the preliminary investigation. Furthermore, the private prosecutor was not around at the time the public prosecutor recommended bail. Respondent Judge stated that in any case, the bailbond posted by accused was cancelled and

a warrant for his arrest was issued on account of complainants motion for reconsideration. The Assistant Provincial Prosecutor apparently conformed to and approved the motion for reconsideration.Accused is confined at the La Union Provincial Jail. On August 14 1995, in a sworn letter-complaint, complainant Basco charged respondent Judge Leo M. Rapatalo with gross ignorance or willful disregard of established rule of law for granting bail to an accused in a murder case without receiving evidence and conducting a hearing. ISSUE: CAN A JUDGE SET BAIL EVEN W/O CONDUCTING A HEARING OR RECEIVING EVIDENCE? HELD: Nope. DISPOSITIVE: WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, respondent Judge Leo M. Rapatalo, RTC, Branch 32, Agoo, La Union, is hereby REPRIMANDED with the WARNING that a repetition of the same or similar acts in the future will be dealt with more severely. HELD: If the denial of bail is authorized in capital offenses, it is only in theory that the proof being strong, the defendant would flee, if he has the opportunity, rather than face the verdict of the court. Hence the exception to the fundamental right to be bailed should be applied in direct ratio to the extent of probability of evasion of the prosecution. In practice, bail has also been used to prevent the release of an accused who might otherwise be dangerous to society or whom the judges might not want to release. It is in view of the abovementioned practical function of bail that it is not a matter of right in cases where the person is charged with a capital offense punishable by death, reclusion perpetua or life imprisonment. Article 114, section 7 of the Rules of Court, as amended, states, No person charged with a capital offense, or an offense punishable by reclusion perpetua or life imprisonment when the evidence of guilt is strong, shall be admitted to bail regardless of the stage of the criminal action. When the grant of bail is discretionary, the prosecution has the burden of showing that the evidence of guilt against the accused is strong. However, the determination of whether or not the evidence of guilt is strong, being a matter of judicial discretion, remains with the judge. This discretion by the very nature of things, may rightly be exercised only after the evidence is submitted to the court at the hearing. Since the discretion is directed to the weight of the evidence and since evidence cannot properly be weighed if not duly exhibited or produced before the court, it is obvious that a proper exercise of judicial discretion requires that the evidence of guilt be submitted to the court, the petitioner having the right of cross examination and to introduce his own evidence in rebuttal. To be sure, the discretion of the trial court, is not absolute nor beyond control. It must be sound, and exercised within reasonable bounds. Judicial discretion, by its very nature involves the exercise of the judges individual opinion and the law has wisely provided that its exercise be guided by well-known rules which, while allowing the judge rational latitude for the operation of his own individual views, prevent them from getting out of control. Consequently, in the application for bail of a person charged with a capital offense punishable by death,reclusion perpetua or life imprisonment, a hearing, whether summary or otherwise in the discretion of the court, must actually be conducted to determine whether or not the evidence of guilt against the accused is strong. On such hearing, the court does not sit to try the merits or to enter into any nice inquiry as to the weight that ought to be allowed to the evidence for or against the accused, nor will it speculate on the outcome of the trial or on what further evidence may be therein offered and admitted. The course of inquiry may be left to the discretion of the court which may confine itself to receiving such evidence as has reference to substantial matters, avoiding unnecessary thoroughness in the examination and cross examination. If a party is denied the opportunity to be heard, there would be a violation of procedural due process.

The cited cases (w/c I didnt include kse madami) are all to the effect that when bail is discretionary, a hearing, whether summary or otherwise in the discretion of the court, should first be conducted to determine the existence of strong evidence, or lack of it, against the accused to enable the judge to make an intelligent assessment of the evidence presented by the parties. Since the determination of whether or not the evidence of guilt against the accused is strong is a matter of judicial discretion, the judge is mandated to conduct a hearing even in cases where the prosecution chooses to just file a comment or leave the application for bail to the discretion of the court. A hearing is likewise required if the prosecution refuses to adduce evidence in opposition to the application to grant and fix bail. Corollarily, another reason why hearing of a petition for bail is required, as can be gleaned from the Tucay v.Domagas, is for the court to take into consideration the guidelines set forth in Section 6, Rule 114 of the Rules of Court in fixing the amount of bail. This Court, in a number of cases held that even if the prosecution fails to adduce evidence in opposition to an application for bail of an accused, the court may still require that it answer questions in order to ascertain not only the strength of the state s evidence but also the adequacy of the amount of bail. After hearing, the courts order granting or refusing bail must contain a summary of the evidence for the prosecution. On the basis thereof, the judge should then formulate his own conclusion as to whether the evidence so presented is strong enough as to indicate the guilt of the accused. Otherwise, the order granting or denying the application for bail may be invalidated because the summary of evidence for the prosecution which contains the judges evaluation of the evidence may be considered as an aspect of procedural due process for both the prosecution and the defense. An evaluation of the records in the case at bar reveals that respondent Judge granted bail to the accused without first conducting a hearing to prove that the guilt of the accused is strong despite his knowledge that the offense charged is a capital offense in disregard of the procedure laid down in Section 8, Rule 114 of the Rules of Court as amended by Administrative Circular No. 12-94. Respondent judge admittedly granted the petition for bail based on the prosecutions declaration not to oppose the petition. Respondents assertion, however, that he has a right to presume that the prosecutor knows what he is doing on account of the latters familiarity with the case due to his having conducted the preliminary investigation is faulty. Said reasoning is tantamount to ceding to the prosecutor the duty of exercising judicial discretion to determine whether the guilt of the accused is strong. Judicial discretion is the domain of the judge before whom the petition for provisional liberty will be decided. The mandated duty to exercise discretion has never been reposed upon the prosecutor. The absence of objection from the prosecution is never a basis for granting bail to the accused. It is the courts determination after a hearing that the guilt of the accused is not strong that forms the basis for granting bail. Respondent Judge should not have relied solely on the recommendation made by the prosecutor but should have ascertained personally whether the evidence of guilt is strong. After all, the judge is not bound by the prosecutors recommendation. Moreover, there will be a violation of due process if the respondent Judge grants the application for bail without hearing since Section 8 of Rule 114 provides that whatever evidence presented for or against the accuseds provisional release will be determined at the hearing. The practice by trial court judges of granting bail to the accused when the prosecutor refuses or fails to present evidence to prove that the evidence of guilt of the accused is strong can be traced to the case ofHerras Teehankee v. Director of Prisons. It is to be recalled that Herras Teehankee was decided 50 years ago under a completely different factual milieu. Haydee Herras Teehankee was indicted under a law dealing with treason cases and collaboration with

the enemy. The said instructions given in the said case under the 1940 Rules of Court no longer apply due to the amendments introduced in the 1985 Rules of Court. It should be noted that there has been added in Section 8 crucial sentence The evidence presented during the bail hearings shall be considered automatically reproduced at the trial, but upon motion of either party, the court may recall any witness for additional examination unless the witness is dead, outside of the Philippines or otherwise unable to testify. is not found in the counterpart provision, Section 7, Rule 110 of the 1940 Rules of Court. The above-underscored sentence in section 8, Rule 114 of the 1985 Rules of Court, as amended, was added to address a situation where in case the prosecution does not choose to present evidence to oppose the application for bail, the judge may feel duty-bound to grant the bail application. The prosecution under the revised provision is duty bound to present evidence in the bail hearing to prove whether the evidence of guilt of the accused is strong and not merely to oppose the grant of bail to the accused. However, the nature of the hearing in an application for bail must be equated with its purpose i.e., to determine the bailability of the accused. If the prosecution were permitted to conduct a hearing for bail as if it were a full-dress trial on the merits, the purpose of the proceeding, which is to secure the provisional liberty of the accused to enable him to prepare for his defense, could be defeated. At any rate, in case of a summary hearing, the prosecution witnesses could always be recalled at the trial on the merits. In the light of the applicable rules on bail and the jurisprudential principles just enunciated, SC reiterated the duties of the trial judge in case an application for bail is filed: (1) Notify the prosecutor of the hearing of the application for bail or require him to submit his recommendation (Section 18, Rule 114 of the Rules of Court as amended); (2) Conduct a hearing of the application for bail regardless of whether or not the prosecution refuses to present evidence to show that the guilt of the accused is strong for the purpose of enabling the court to exercise its sound discretion (Sections 7 and 8, supra); (3) Decide whether the evidence of guilt of the accused is strong based on the summary of evidence of the prosecution (Baylon v. Sison); (4) If the guilt of the accused is not strong, discharge the accused upon the approval of the bailbond. (Section 19, supra). Otherwise, petition should be denied. The above-enumerated procedure should now leave no room for doubt as to the duties of the trial judge in cases of bail applications

JOSE ANTONIO LEVISTE, G.R. No. 189122 Petitioner,THE COURT OF APPEALSand PEOPLE OF THEPHILIPPINES, THE FACTS Charged with the murder of Rafael de las Alas, petitioner Jose Antonio Leviste wasconvicted by the Regional Trial Court of Makati City for the lesser crime of homicide andsentenced to suffer an indeterminate penalty of six years and one day of prision mayor asminimum to 12 years and one day of reclusion temporal

as maximum. [11] He appealed his conviction to the Court of Appeals. [12] Pending appeal, he filed anurgent application for admission to bail pending appeal, citing his advanced age and healthcondition, and claiming the absence of any risk or possibility of flight on his part. The Court of Appeals denied petitioners application for bail. [13] It invoked the bedrockprinciple in the matter of bail pending appeal, that the discretion to extend bail during thecourse of appeal should be exercised with grave caution and only for strong reasons.Petitioners motion for reconsideration was denied. [15] Petitioner quotes Section 5, Rule 114 of the Rules of Court was present. Petitionerstheory is that, where the penalty imposed by the trial court is more than six years but not morethan 20 years and the circumstances mentioned in the third paragraph of Section 5 areabsent, bail must be granted to an appellant pending appeal. THE ISSUE Whether the discretionary nature of the grant of bail pending appeal mean that bailshould automatically be granted absent any of the circumstances mentioned in the thirdparagraph of Section 5, Rule 114 of the Rules of Court? Section 5, Rule 114 of the Rules of Court provides: S e c . 5 . Bail, when discretionary . Upon conviction by theR e g i o n a l T r i a l C o u r t o f a n o f f e n s e n o t p u n i s h a b l e b y death, reclusion perpetua , o r l i f e i m p r i s o n m e n t , a d m i s s i o n t o b a i l i s discretionary . The application for bail may be filed and acted upon by thet r i a l c o u r t d e s p i t e t h e f i l i n g o f a n o t i c e o f a p p e a l , p r o v i d e d i t h a s n o t transmitted the original record to the appellate court. However, if the decisionof the trial court convicting the accused changed the nature of the offensefrom nonbailable to bailable, the application for bail can only be filed withand resolved by the appellate court. I f t h e p e n a l t y i m p o s e d b y t h e t r i a l c o u r t i s i m p r i s o n m e n t exceedi ng six (6) years, the accused shall be denied bail, or his bailshall be cancelled upon a showing by the prosecution, with notice tothe accused, of the following or other similar circumstances: (a) That he is a recidivist, quasi-recidivist, or h a b i t u a l d e l i n q u e n t , o r h a s c o m m i t t e d t h e c r i m e a g g r a v a t e d b y t h e circu mstance of reiteration; (b) That he has previously escaped from legal confinement,evaded sentence, or violated the conditions of his bail without avalid justification

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Ppol Vs Sy ChuaDocument14 paginiPpol Vs Sy Chuamichelle_calzada_1Încă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest: People V Binad Sy ChuaDocument3 paginiCase Digest: People V Binad Sy ChuaJune Karla LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs Sy ChuaDocument3 paginiPeople Vs Sy ChuaMyra MyraÎncă nu există evaluări

- People v. ChuaDocument2 paginiPeople v. ChuaChou TakahiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- People V ChuaDocument6 paginiPeople V ChuaJeremiah ReynaldoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Police Privacy BalanceDocument90 paginiPolice Privacy BalanceHartel BuyuccanÎncă nu există evaluări

- PP Vs Sy ChuaDocument2 paginiPP Vs Sy ChuafaithreignÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs Sy ChuaDocument3 paginiPeople Vs Sy ChuaJessamine OrioqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs chuaDocument11 paginiPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs chuaARCHIE AJIASÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. Binad ChuaDocument12 paginiPeople vs. Binad ChuaJillen SuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stop-and-Frisk Doctrine in Drug CasesDocument8 paginiStop-and-Frisk Doctrine in Drug CasesMichael ArgabiosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- THE CASE-PEOPLE VS. AMMINUDIN (163 SCRA 402 G.R. L-74869 6 Jul 1988)Document8 paginiTHE CASE-PEOPLE VS. AMMINUDIN (163 SCRA 402 G.R. L-74869 6 Jul 1988)Michael ArgabiosoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consti II Cases Page 3Document51 paginiConsti II Cases Page 3Rae ManarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dela Cruz vs. People G.R. No. 200748, July 23, 2014 Facts: Petitioner Jaime D. Dela Cruz Was Charged With Violation of Section 15, Article II ofDocument20 paginiDela Cruz vs. People G.R. No. 200748, July 23, 2014 Facts: Petitioner Jaime D. Dela Cruz Was Charged With Violation of Section 15, Article II ofredlacsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Castaño Criminal-Procedure Case-DigestsDocument26 paginiCastaño Criminal-Procedure Case-DigestsStephen Neil Casta�oÎncă nu există evaluări

- ArrestDocument182 paginiArrestELEAZAR CALLANTAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warrantless Search ExceptionsDocument3 paginiWarrantless Search ExceptionsElla B.67% (3)

- Homar v. People DigestDocument1 paginăHomar v. People DigestQueen PañoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warrantless Searches and SeizuresDocument31 paginiWarrantless Searches and Seizuresdragon knightÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judge's Discretion in Issuing Arrest WarrantsDocument6 paginiJudge's Discretion in Issuing Arrest WarrantsJon SnowÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. EdanoDocument3 paginiPeople vs. EdanoVilpa VillabasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pros. Maychelle A. Isles: Office of The Provincial Prosecutor of AlbayDocument92 paginiPros. Maychelle A. Isles: Office of The Provincial Prosecutor of AlbayRacel AbulaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cases 11 and 12Document4 paginiCases 11 and 12John Ceasar Ucol ÜÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cannot Be Made in A Place Other Than The Place of Arrest. (Nolasco) - HasDocument17 paginiCannot Be Made in A Place Other Than The Place of Arrest. (Nolasco) - HasJoahnna Paula CorpuzÎncă nu există evaluări

- People v. Montilla (Dela Cruz)Document2 paginiPeople v. Montilla (Dela Cruz)Berenice Joanna Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court Rule on Chain of CustodyDocument24 paginiSupreme Court Rule on Chain of CustodyJoanna Felisa GoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crimproc - Rule 113 ArrestDocument6 paginiCrimproc - Rule 113 ArrestDethivire EstupapeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asian Surety vs Herrera ruling on search warrant validityDocument21 paginiAsian Surety vs Herrera ruling on search warrant validitylouis jansenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valid Arrest in Drug CaseDocument16 paginiValid Arrest in Drug Caseyannie isananÎncă nu există evaluări

- Title V Case DigestsDocument15 paginiTitle V Case DigestsAnonymous hbUJnB0% (1)

- Search and Seizure RulingsDocument4 paginiSearch and Seizure RulingsHonshouÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. Dela Cruz ruling on possession of drugsDocument10 paginiPeople vs. Dela Cruz ruling on possession of drugsjanzÎncă nu există evaluări

- 109 People Vs CogaedDocument4 pagini109 People Vs CogaedRae Angela GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- People v. Dalawis y Hidalgo, G.R. No. 197925Document10 paginiPeople v. Dalawis y Hidalgo, G.R. No. 197925Henri Ana Sofia NicdaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zalameda v. PeopleDocument4 paginiZalameda v. PeopleAnonymous wDganZÎncă nu există evaluări

- People of The Philippines, Plaintiff-Appellee, V. Jayson Torio Y Paragas at "BABALU," Accused-Appellant. G.R. No. 225780, December 03, 2018Document3 paginiPeople of The Philippines, Plaintiff-Appellee, V. Jayson Torio Y Paragas at "BABALU," Accused-Appellant. G.R. No. 225780, December 03, 2018Jessette Amihope CASTORÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consti Compilation 3Document46 paginiConsti Compilation 3MariaAyraCelinaBatacanÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs EdanoDocument3 paginiPeople Vs EdanoWresen Ann100% (1)

- Arrest Without Warrant ExceptionsDocument7 paginiArrest Without Warrant Exceptionslicarl benitoÎncă nu există evaluări

- People v. Chua, 396 SCRA 657Document14 paginiPeople v. Chua, 396 SCRA 657aitoomuchtvÎncă nu există evaluări

- CrimLaw1 Cases 149-152Document7 paginiCrimLaw1 Cases 149-152Dennis Jay Dencio ParasÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. Chua, 396 SCRA 657, February 04, 2003 Case DigestDocument4 paginiPeople vs. Chua, 396 SCRA 657, February 04, 2003 Case DigestElla Kriziana CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recent Jurisprudence On Illegal Drugs CasesDocument33 paginiRecent Jurisprudence On Illegal Drugs CasesAlbert AzuraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warrantless Arrest and Search and Seizure (In Flagrante Delicto Arrest)Document1 paginăWarrantless Arrest and Search and Seizure (In Flagrante Delicto Arrest)MariaFaithFloresFelisartaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warrantless Arrests InvalidDocument5 paginiWarrantless Arrests InvalidRaedavy OpisanÎncă nu există evaluări

- People V Romy LimDocument3 paginiPeople V Romy LimStephanie TumulakÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. RodriguezaDocument8 paginiPeople vs. RodriguezaBrian Balio100% (1)

- Crim Pro Digest 2nd Batch (Atty Cabigas)Document6 paginiCrim Pro Digest 2nd Batch (Atty Cabigas)Mark Adrian ArellanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crim Pro Case DigestDocument20 paginiCrim Pro Case DigestMaria Josephine Olfato PanchoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crimpro Case Digest 04-14-2023Document45 paginiCrimpro Case Digest 04-14-2023Frances JR SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warrantless Search People Vs Leangsiri FactsDocument4 paginiWarrantless Search People Vs Leangsiri FactsJoahnna Paula CorpuzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consti CompilationDocument209 paginiConsti CompilationMariaAyraCelinaBatacanÎncă nu există evaluări

- People of The Philippines vs. Binad Sy ChuaDocument1 paginăPeople of The Philippines vs. Binad Sy ChuaNerrak GesulgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ) People of The Philippines V. Jesus Nuevas, Et. Al. G.R. No. 170233Document21 pagini) People of The Philippines V. Jesus Nuevas, Et. Al. G.R. No. 170233cristine jagodillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument38 paginiCase DigestKIERSTINE MARIE BARCELO100% (1)

- Arbitrary Detention and Delay in Delivery of Detained PersonsDocument186 paginiArbitrary Detention and Delay in Delivery of Detained PersonsFe PortabesÎncă nu există evaluări

- A2. People v. PagaduanDocument10 paginiA2. People v. PagaduanMarie ReloxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criminal Law Homicide: Degrees of Murder and DefensesDe la EverandCriminal Law Homicide: Degrees of Murder and DefensesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World's Dumbest Criminals: Outrageously True Stories of Criminals Committing Stupid CrimesDe la EverandThe World's Dumbest Criminals: Outrageously True Stories of Criminals Committing Stupid CrimesEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (3)

- Criminology Board Exam Reviewer Questions and AnswDocument4 paginiCriminology Board Exam Reviewer Questions and AnswGretchen Barrera Patenio78% (9)

- Criminology Board Exam Reviewer Questions and AnswDocument4 paginiCriminology Board Exam Reviewer Questions and AnswGretchen Barrera Patenio78% (9)

- What Is Corona VirusDocument4 paginiWhat Is Corona VirusKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 143193Document10 paginiG.R. No. 143193Kuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Holland Code Test PDFDocument5 paginiHolland Code Test PDFIonelia PașaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Qand A Corona VirusDocument5 paginiQand A Corona VirusKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Qand A Corona VirusDocument5 paginiQand A Corona VirusKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Free Psychometric Test Questions Answers PDFDocument23 paginiFree Psychometric Test Questions Answers PDFKonul Alizadeh57% (7)

- How COVIDDocument2 paginiHow COVIDKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here Are 24 Pointers To Review For Your Examination in Criminal Law 2Document7 paginiHere Are 24 Pointers To Review For Your Examination in Criminal Law 2Kuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Coronavirus and What Should I Do If I Have SymptomsDocument3 paginiWhat Is Coronavirus and What Should I Do If I Have SymptomsKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thought LeadersDocument2 paginiThought LeadersKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

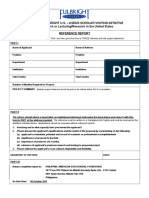

- 2018 19 US ASEAN Fulbright Initiative LoRDocument1 pagină2018 19 US ASEAN Fulbright Initiative LoRKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018 Criminal Law Bar Examination Syllabus PDFDocument3 pagini2018 Criminal Law Bar Examination Syllabus PDFKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personality TestDocument1 paginăPersonality TestKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Forgotten TreatyDocument4 paginiThe Forgotten TreatyKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personality TestDocument1 paginăPersonality TestKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018 Criminal Law Bar Examination Syllabus PDFDocument3 pagini2018 Criminal Law Bar Examination Syllabus PDFKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criminal Compalint ProsecDocument24 paginiCriminal Compalint ProsecKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- NIA Mariis Division III Office Address, Contact DetailsDocument8 paginiNIA Mariis Division III Office Address, Contact DetailsKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- San Beda College of Law Memory Aid in Torts and DamagesDocument32 paginiSan Beda College of Law Memory Aid in Torts and DamagesDrew MGÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Irrigation Administration: Part 1. EssayDocument8 paginiNational Irrigation Administration: Part 1. EssayKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Astorga vs. PeoplefactsDocument9 paginiAstorga vs. PeoplefactsKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Forgotten TreatyDocument4 paginiThe Forgotten TreatyKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alcantara V ComelecDocument2 paginiAlcantara V ComelecKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is EntrepreneurshipDocument3 paginiWhat Is EntrepreneurshipKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparative Matrix of Social Legislation in The Philippines 01Document14 paginiComparative Matrix of Social Legislation in The Philippines 01Kuthe Ig Toots100% (1)

- Supreme Court's 2011 Bar Exams MCQ - Commercial LawDocument22 paginiSupreme Court's 2011 Bar Exams MCQ - Commercial LawATTY. R.A.L.C.Încă nu există evaluări

- Treaty of ParisDocument2 paginiTreaty of ParisKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arubaopposition PDFDocument9 paginiArubaopposition PDFKuthe Ig TootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs LeangsiriDocument2 paginiPeople Vs LeangsirijovifactorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Professional Responsibility - Chemerinsky Sum & Substance Lecture Notes AlstonDocument6 paginiProfessional Responsibility - Chemerinsky Sum & Substance Lecture Notes AlstonSean ScullionÎncă nu există evaluări

- C3h - 5 Tison v. CaDocument3 paginiC3h - 5 Tison v. CaAaron AristonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rivera V ComelecDocument2 paginiRivera V ComelecArlene Q. SamanteÎncă nu există evaluări

- PNP Sop Involving Armored CarsDocument3 paginiPNP Sop Involving Armored CarsJudel K. Valdez75% (4)

- JJB - Juvenile Justice Board ExplainedDocument11 paginiJJB - Juvenile Justice Board ExplainedDeepak KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five Styles of Dominance QuizDocument4 paginiFive Styles of Dominance QuizMike100% (2)

- Adjudication Order in Respect of Sendhaji J Thakor in The Matter of SEL Manufacturing Co LTDDocument7 paginiAdjudication Order in Respect of Sendhaji J Thakor in The Matter of SEL Manufacturing Co LTDShyam SunderÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 Features of Administrative LawDocument4 pagini5 Features of Administrative LawLUCAS67% (3)

- Paritala RaviDocument7 paginiParitala Ravibhaskarchow100% (4)

- Chetan Bhagat: in The Hon'Ble City Civil and Sessions CourtDocument5 paginiChetan Bhagat: in The Hon'Ble City Civil and Sessions CourtKishan PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gloria V CA GR 119903Document6 paginiGloria V CA GR 119903Jeng PionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippines Correctional System ExplainedDocument4 paginiPhilippines Correctional System ExplainedRandal's CaseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Opposition To Motion To Strike For CaliforniaDocument3 paginiSample Opposition To Motion To Strike For CaliforniaStan Burman100% (3)

- Kar Lokayukta Act 1984 PDFDocument19 paginiKar Lokayukta Act 1984 PDFNaveen KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ford PintoDocument3 paginiFord PintoNoor FazlitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Safety KitDocument28 paginiChild Safety Kiter_ashishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moncupa V PonceDocument2 paginiMoncupa V PonceLuna Baci100% (1)

- Legal Profession | Solicitation of CasesDocument7 paginiLegal Profession | Solicitation of CasesJonjon BeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Violation of Verification and CertificationDocument6 paginiViolation of Verification and CertificationWreigh Paris100% (1)

- People v. Andre Marti GR 81561 January 18, 1991Document6 paginiPeople v. Andre Marti GR 81561 January 18, 1991Mary Kaye ValerioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Probable Cause Affidavit Against Carl BlountDocument10 paginiProbable Cause Affidavit Against Carl BlountjpuchekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complaint of Judicial Misconduct Against Judge T.S. Ellis, IIIDocument6 paginiComplaint of Judicial Misconduct Against Judge T.S. Ellis, IIIJ. Whitfield Larrabee100% (4)

- Digested CasesDocument4 paginiDigested CasesKenny Robert'sÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2017 Fed Final, 279, 7-14-17,#799 LibreDocument279 pagini2017 Fed Final, 279, 7-14-17,#799 Librebruce rÎncă nu există evaluări

- RTC Branch 87 Answer Denies Plaintiff's ClaimsDocument6 paginiRTC Branch 87 Answer Denies Plaintiff's ClaimsConcepcion CejanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- People V MatheusDocument2 paginiPeople V MatheusJb BuenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taguinod vs. PPDocument6 paginiTaguinod vs. PPJoshua CuentoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Turkish CapitulationsDocument7 paginiTurkish Capitulationsrobnet-1Încă nu există evaluări

- Frauds PDFDocument35 paginiFrauds PDFRaissa Ericka RomanÎncă nu există evaluări