Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Line Light. The Geometric Cinema of Anthony McCall

Încărcat de

dr_benwayTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Line Light. The Geometric Cinema of Anthony McCall

Încărcat de

dr_benwayDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Line Light: The Geometric Cinema of Anthony McCall*

PHILIPPE-ALAIN MICHAUD

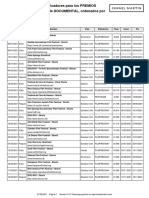

Line Describing a Cone (1973), the first of Anthony McCalls geometric films, has recently reawakened keen interest. In 2001, it appeared in the Whitney Museum of American Arts exhibition Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art, 19641977, curated by Chrissie Iles. In 2003, October published a group of texts on The Projected Image in American Art of the 1960s and 1970s, including the lecture delivered by McCall during the Whitneys exhibition. Since then, discussion of this artist/filmmakers work has steadily increased.1 The revival of interest can be seen as the effect of filmmakings migration toward the art world, a movement for which McCalls film stands as an emblematic prefiguration, indeed as a totemic one. Over the last three decades, Line Describing a Cone has, in fact, been presented in contexts of both the art scene and the filmic avant-garde, demonstrating that it has provided a bridge between two worlds until then quite severed from each other. Procedure Line Describing a Cone , conceived in Januar y 1973, t wo days out of Southampton during McCalls journey by boat from England to the States, was made in New York in August of that year for one hundred dollars. In 2002, during a retrospective devoted to the history of the London Film-Makers Co-op, to which his cinema has been closely linked, he stated: Once I really started working with film and feeling I was making films, making works of media, it seemed to me a completely natural thing to come back and back and back, to come more away from a pro-filmic event and into the process of filmmaking itself. And at the time it all boiled down to some very simple questions. In my case, and perhaps in

* A version of this essay appeared in Cahiers du Muse national dart moderne 93 (Fall 2003), pp. 7889. 1. Anthony McCall, Line Describing a Cone and Related Films, October 103 (Winter 2003), pp. 4262. See The Projected Image in Contemporary Art, a roundtable discussion with McCall, George Baker, Matthew Buckingham, Hal Foster, Chrissie Iles, and Malcolm Turvey, in October 104 (Spring 2003), pp. 7196. See also Anthony McCall, Film Installations, exh. cat. (Warwick: Mead Gallery, 2004); and Christopher Eamon, ed., The Solid Light Films and Related Works (Evanston: Northwestern University, 2005). OCTOBER 137, Summer 2011, pp. 322. 2011 October Magazine, Ltd. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

OCTOBER

others, the question being something like What would a film be if it was only a film? Carolee Schneemann and I sailed on the SS Canberra from Southampton to New York in 1973, and when we embarked, all I had was that question. When I disembarked I already had the plan for Line Describing a Cone fully-fledged in my notebook. You could say it was a mid-Atlantic film! Its been the story of my life ever since, of course, where Im located, where my interests are, that business of Am I English or am I Amer ican? So that was when I conceived Line Describing a Cone and then I made it in the months that followed.2 For McCall, Line is a narrative film of conventional structure: a long progression toward a climax followed by a sudden denouement that coincides with the end of the piece. Shot as an animation, one frame at a time, Line shows the gradual forming of a white circle on a black background. The circle being photographed had been drawn on a sheet of black paper using white gouache, ruling-pen, and compass.3 The film is to be projected, not in a theater but in an exhibition space that is closed off, homogeneous, non-hierarchized, and level, with no separation between projection space and spectators, no rows of chairs, and, above all, no screen. An essential point: mist is diffused throughout the projection, so that the image of the circle projected on the screens surface is replaced by the projectors light beam, which takes on a material consistency.4 The film shows the formation of a geometrical body in space caused by the projection of a simple light beam, and insofar as it becomes a narrative, it is the visual narrative of this materialization. According to McCall, the ideal length of the beam (the distance between projector and surface of projection, or between the light source and the beams plane of intersection) is between thirty and fifty feet, with the diameter of the circle on the wall being between seven and nine feet, and the base of the circle about twelve inches from the ground. A spectator with raised arms, standing inside the cone and against the wall on which the circle is projected, is unable to touch the surface of the cone. If one walks towards the light source, the membrane of light gradually diminishes in size until one emerges out of it. As one reaches the projector, it is possible to see the ribbon of filmstock passing behind the lens, and on it the circles tiny image, the bi-dimensional image that is the source of the tri-dimensional one.5

2. McCall, interview with Mark Webber, 2001, quoted in Shoot, Shoot, Shoot: The First Decade of the London Film-Makers Cooperative and British Avant-Garde Film, 19661976, unpublished broadsheet, 2002, distributed by London Film-Makers Cooperative in conjunction with the eponymous exhibition that opened at Tate Modern in May 2002. 3. The prints for projection, which display the same relation of black background and white line, are inter-negatives. 4. From 1972 to 1974, McCall created a series of pyrotechnic pieces, starting with Landscape for Fire I, presented in England, the United States, and Sweden. Line is their luminescent extension. These were outdoor installations based on grids defined by small containers of inflammable liquid. Following a precise score, the fires were lit in a specific order to create shifting configurations within the grid. 5. One finds the same concern with the volumetric display of projection in Take Measure (made in 1973, the same year as Line) by William Raban, a major figure in the British school of Structural work. The filmstrip, whose length coincides exactly with that of the projection space, is unwound

Anthony McCall. Line Describing a Cone. 1973. Installation view during the twenty-fourth minute, the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2002. Photograph by Hank Graber.

McCall. Line Describing a Cone. 1973. Installation view during the twenty-fourth minute, the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2002. Photograph by Hank Graber.

Line Light

The spectator turns from the screen to catch sight of the light source; this turn is prefigured in a slide work of 1972, Miniature in Black & White, in which a series of slides pass repeatedly before a projector lens, showing tiny plants pasted between two pieces of transparent glass in alternation with sections of black leader, lines, scratches, and sprocket holes. The slides are projected onto a tiny screen immediately in front of the projector lens. The spectator is invited to stand close to the screen, in effect looking directly into the light, thereby experiencing projection optically in its pure state, an experience of which Line will be both the expansion and the reversal. Although the films construction is wholly the product of calculation, one parameter of an aleatoric kind does persist in projection. In 1974, during a joint screening by New Yorks Collective for Living Cinema and Film Forum in a high-ceilinged 100by50 foot space, for approximately 120 spectators and with a projector equipped with a very powerful xenon bulb, the circle produced was about three meters high and McCall says he had the impression of seeing the film for the first time. It had nothing to do with the work Id conceived.7 For the first projections, McCall counted on the dust-filled air of New York lofts, and he mentions projections of Line organized with simple incense sticks or in the presence of cigarette-smoking spectators. With the rising cult of the clean and healthy, dust disappeared from lofts along with the art lovers tobacco. Projections of Line are now done with theatrical mist machines. Having seen this as a distortion of the initial project, McCall came to consider the set-up as a possible non-narrative version of the film, with neither beginning nor end, thus transforming the course of action into a formal statement. Geometry In a note written for the Knokke-le-Zoute Festival of 1974, McCall wrote, Line Describing a Cone is what I term a solid light film. It deals with the projected light beam itself, rather than treating the light beam as a mere carrier of coded information, which is decoded when it strikes a flat surface.8 With McCalls film, the space of conventional cinemawhich is based on the traditional theaters separation of spectator from performance and constructed according to an ideal, single, fixed point of viewcomes apart. That configuration, the traditional design of the theater dominant throughout the t went ieth centur y, depends on the forgett ing of the phenomenon of projection: the screen functions as a window within which an illusionist spatial perspectivea fictive spaceis reconstituted. For the perspectival space of conventional cinema, McCall substitutes a projective space. The wall no longer opens out as a transparent window, but appears as an opaque surface and as a limit. Line even develops as the inversion of the perspectival set-up insofar as the

between the screen and the projector. When the latter starts up, the film reel leaves the screens surface, to be restored, by an inverse symmetrical movement, in a luminous form. 6. In reminiscence of Stan Brakhages Mothlight, made in 1963. 7. Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (Berkeley: University of California, 1992), p. 162. 8. McCall, Line Describing a Cone and Related Films, p. 43.

OCTOBER

cones apex no longer coincides with the vanishing point on the horizon line behind the screen but rather with the source of the light beam formed in the projectors lens.9 In overturning the fictive depth beyond the screen and directing it toward the real depth that unfolds beyond it, Line opens filmic experience to tri-dimensionality.10 From now on, film is no longer that projected image hollowing out a semblance of depth within the walls surface but a field truly formed by and merged with the projection itself. In this way, the light beams inscribed within McCalls mist develop films real plastic properties, crossing the frontiers of film history. In so doing, they emerge, like Dan Flavins color fields or Fred Sandbacks colored strings of cotton, stretched out through space, as modulations of the space within which they fan out. In 1974, with the base provided by Line, McCall conceived and executed a series of filmic variations on the geometrical figure of the conePartial Cone, Conical Solid, and Cone of a Variable Volumein which the deconstruction of cinematic expression initiated by Line was extended. Partial Cone explores the textural modulations of the light beamof solid to glimmering, flickering, and flashingobtained by the insertion of an increased number of black frames between the areas of pure light. In Conical Solid, a flat light beam revolves around a fixed central axis. Cone of a Variable Volume is the registration of the conical module phenomenon of accelerating expansion and concentration. For the latter film, the circle was drawn prior to filming, with the animation obtained by the cameras withdrawal from and approach to the previously drawn circle. The three Cone films revisit, in simple form, a specific property of the original cone of which they form the analytic decomposition. The following geometrical films will, on the other hand, represent an enlargement of the set-up. Long Film for Four Projectors (1974), later shown at Documenta 6 (1977), thus seems like an expansion of Line. The installation is composed of four projectors. Spectators circulate within a vast, mist-filled, rectangular space with four intersecting light beams forming arcs of ninety degrees; the presentation of the volumetric object (Lines cone) is transformed into an environment. The spectator is now inside the film, no longer conceived as a circumscribed form within a predefined space but as the very field within which the experience takes shape. The film, with a running time of six hours, is composed of forty-five-minute modules in eight permutations, so as to include all possible combinations of the four movements. In 1975, McCall made Four Projected Movements, which, like Lines three geometrical sequels, appears as the analytic decomposition of Long Film for Four Projectors. This is a piece for a single projector

9. This reversal coincides with antiquitys construction of the visual cone of geometrical perspective. According to this hypothesis of Pythagorean origin, the visual beam cast by the eye travels in a straight line to strike the object of the gaze. This model made it possible to trace a visual cone with its summit at the eyes center and its base at the pupil, to determine the visual field and to draw the angle at which the object was seen. Grard Simon, Archologie de la vision: Loptique, le corps, la peinture (Paris: Seuil, 2003), p. 18. 10. The techniques of 3-D that develop in the commercial cinema from the 1950s onward are based, however, on a fictive dissolving of the boundary between what is within the screen and what is beyond it.

Line Light

installed in a corner of a rectangular space. A fifteen-minute reel emits a beam of light that describes an arc of ninety degrees. The film (16mm with double perforation) is loaded four times in the projector: from beginning to end, from end to beginning, from beginning to end and backwards, and from end to beginning and backwards. The effect as planned is the sensation of four successive displacements: from wall to floor, from ceiling to wall, from wall to floor, and from ceiling to wall. The Four Projected Movements do not, however, form a closed deductive system any more so than Sol LeWitts 122 Variations of Incomplete Open Cubes (1974) are reducible to a demonstration of a logical sort. In McCalls piece, the accent is no longer on the projected image, nor even on the phenomenon of projection, but on the gesture of projection and, as in 122 Variations, on the exhaustion of possibilities.11

11. In this connection, see Rosalind Krausss description of the LeWitt piece in terms of the parable of the pebbles developed by Samuel Beckett in Molloy, LeWitt in Progress, in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1985). On the Beckett-like combinatorial see The Exhausted, in Gilles Deleuze: Essays Critical and Clinical, trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), p. 18.

McCall. Installation drawing for Long Film for Four Projectors. 1977.

McCall. Installation drawings for Four Projected Movements. 1975.

12

OCTOBER

Long Film for Ambient Light, the last of McCalls geometrical films, created in June 1975 at the Idea Warehouse, is the most radical as well. Its running time is twenty-four hours. The gallerys windows are covered with white paper, through which daylight can pass; at night, the light from a bulb hanging from the ceiling is refracted on the sheets of paper, which are thereby transformed into screens.12 The spectators are free to come and go and, above all, to return, so as to take account of the slow changes of light that represent the entire filmic event. All elements of the filmic spectacle (projector, screen, film strip, and even spectator) have disappeared; light and duration remain.

Astronomy At the beginning of the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant, in describing the reversal of perspective involved in the critical method, uses the term Copernican Revolution; this is directed at substituting, for the immediacy of the object within the process of knowledge, the examination of those faculties of the subject by which that process is conditioned. Line and its sequels present, similarly, a critical reversal of films progress from projected image to the projective mechanism itself.13 The discovery of Lines principle mid-Atlantic, in the middle of nowhere,

12. In 1966, Malcolm Le Grice had offered in Castle 1 the same type of deconstruction of the cinematic experience by hanging, along the screens side, a lightbulb that flashed on and off during the projection. 13. Nol Burch refers to a projection setup at the beginning of Japanese cinema in which the spectators benches were placed not facing the screen but along the ray of light. McCalls piece would thus present a trace of this original fascination with the projective event as such, with the projected image as merely its residual trace. See Nol Burch, To the Distant Observer: Towards a Theory of Japanese Film, October 1 (Spring 1976), p. 36.

McCall. Long Film for Ambient Light. 1975. Installation view, Idea Warehouse, New York.

Line Light

13

McCall. Announcement for Line Describing a Cone. 1974.

thus appears as a kind of dramatization of the account in the Transcendental Aesthetic in which Kant describes the a priori forms of the sensible that condition the subjects apprehension of phenomena: a reduction of the cinematic to its ultimate spatio-temporal elements. Line Describing a Cone is not, however, a Copernican Revolution merely in Kants metaphorical sense, an inversion of the filmic experience for the elucidation of its formal properties; it is a literal reproduction, as well. We know that Copernicuss publication of De revolutionibus orbium caelestium (Venice, 1543) marked heliocentrisms replacement of geocentrism, which would end with Galileo and the mathematization of physics. The result was a series of epistemological reversals, such as the following: The finite, concrete space of medieval physics becomes an abstract space, homogeneous, potentially infinite. The cosmos conceived as a hierarchized space is dissolved. Mans place in the universe is relativized. Finally, in pre-Galilean physics, movement is defined not from the point and instant of departure and the speed of the moving object but rather from the place of arrival and the end toward which the object is directed by a sort of appetite. From now on, end product no longer counts as the cause and explanatory principle of movement. It is precisely this that transpires in McCalls film, on the reduced scale of the cosmos formed by the gallerys white cube transformed into a black box. The displacement of emphasis from the projected image toward the projection phenomenon results in the following: The geometricization of space: the gallerys homogeneous and omnidirectional space replaces the cinemas heterogeneous space, formed as it is by different, qualitatively distinct places (screen, theater, projection booth). The relativization of the spectator, who is now deprived of a fixed, stable

14

OCTOBER

point of reference, the reappraisal of the unidirectional point of view and of the monodirectional point of view. The reappraisal of finality in the cinematographic experience; it is no longer the image projected onscreen (in other words, the final cause) that defines cinema but the projection phenomenon, whose reception surface only marks the end.14 In an interview by Scott McDonald, published in 1992, McCall stated: I had begun to think about the possibility of making a film that would be only film. What were its irreducible elements? My interest in the question was certainly awakened by Peter Gidals texts on Andy Warhol. Most questions during the 1970s revolved around the notion of process and the mediums possibilities as such.15 Line Describing a Cone seems, at first glance, to conform to the principles of Greenbergian essentialism: It returns cinema to the clarification of its own elements (the projection phenomenon). It has a performative dimension, which is explicit in its title: the description of the cone is immediately identical with its realization, so that the aesthetic and theoretical spaces converge; it is this convergence that produces the films specific perceptual effect. The film in question is strictly anti-illusionist, replacing or substituting an effect of real spatialization for a fictive depth. Process replaces exposition of the completed form, and completion of the form thus indicates completion of the piece. The film, self-referential, devoid of incident, is based on a simple geometric progression; it is wholly calculable, since the process is merely the realization of its premises. It is based on a principle of economy (a minimum of means for maximum effect). Finally, it is wholly devoid of reflexivity, its effective source disappearing, replaced by the exposition of process. The film does nevertheless retain something indefinable or nonspecific in its very structure, and McCall has stated that he sees in Line an intermediate state between film and sculpture. The lights lack of consistency and quality, the presence of movement, and the unfolding of the spectacle in the dark are all closely related to cinema. The tri-dimensionality and spatialization, on the other hand, suggest the sculptural. Now, this ambiguity between film and sculpture is the effect of two displacements, the first of which is evident and the other

14. Paul Sharits compares the definalization induced by projection of films on a wall with no screen to Carl Andres gesture. See UR(i)N(ul)LS . . . , in Film Culture 65/66 (1978), p. 11. 15. McCall, quoted in MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 2, p. 160.

Line Light

15

more discreet. They show that Line is not reducible to the elucidation of its formal properties. They demonstrate that even through an attempt to reach its limitreduced, as it were, to it s irreducible element s the nature of the medium does not change as a result of what Aristotle calls generic alteration (metabasis eis allo genos). As evidence, there is the light cones appearance conditioned by the diffusion of the smoke; in other words, the cones appearance is only a reaction to the surroundings; seen thus, the thin beam of light becomes a kind of blade that gradually cuts into the opaque mass of smoke. And when, in 1975, at 2729, rue Beaubourg, Gordon Matta-Clark, in Conical Intersect, a piece conceived in tribute to McCalls film, makes, on the site of the future Pompidou Center, a gigantic cut into a building marked for demolition, he will incidentally reveal the sculptural properties of the filmmakers piece.16 However, this first operation masks a second, more discrete one; the films volumetric effect is conditioned by the lights persistence. Each light eventthat is, each stage of progression along the circles curveis retained, as against the effect of classical projection in which the emission of light is diachronic and ephemeral (the images replace each other). We can therefore form the following hypothesis: when succession is returned to simultaneity, the film changes into sculpture. Paul Sharitss investigations of the shutters optical materialization, as displayed in the installation Shutter Interface (1975), cast new light on the activation of the cone employed in Line. On the wall of a gallery plunged into darkness, a horizontal band of seven partially superimposed rectangles of pure color flash on and off in arithmetically determined combinations. The illusion of the perception of the shutter (that is, the mechanical operation that determines the perception of movement) is obtained through the insertion of a black frame between the areas of color formed by film frames from two to ten in number. Each area of color, followed by black, is perceived as separate, as if it consisted of only one frame. For Sharits, just as for McCall, the point is not to produce the mechanical phenomenon of the shutters action but to dramatize it; it is not about the phenomenological reduction of the cinematic projection, but its reconstruction. And since Line reconstructs rather than deconstructs the projection phenomenon, it opens onto a new form of theatricality.17

16. In 1998, Pierre Huyghe, in Light Conical Intersect, will cover Matta-Clarks film with McCalls by projecting on the wall of the building in the neighborhood of the Clock (the site of Matta-Clarks intervention) an image of Conical Intersect taken at the moment of the lights permeation of the conical cavity made in the faade; in a perfect visual coincidence, the architectural system is resolved into light, thus returning to its origin. 17. McCall claims to have recognized a precedent for his geometric films in HPSCHD (1968), an installation by John Cage in which seven harpsichordists, seated in a circle, play different scores. The sonic chaos is transformed and decomposes in response to the auditors movement around the musicians. Talking of HPSCHD, Cage stated, In each case its a question of developing a form of theater without depending on a text, For the Birds: John Cage in Conversation with Daniel Charles (Boston: Marion Boyars, 1981), p. 166; cited by McCall in October 103, p. 60.

16

OCTOBER

This page: Bruce Nauman. Preparatory drawing for Cones/Cojones. 1974. 2001 Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Next page: Sandro Botticelli. Map of Hell. 148090.

Cosmology In 1975, Bruce Nauman showed Cones/Cojones at the Castelli Gallery.18 A series of concentric circles made of adhesive tape, applied to the gallerys floor, suggested a cut in large interlocking cones running vertically downward ad infinitum. Spectators standing in the drawings center found themselves sucked into a negative structure recalling that of Dantes Inferno, which Botticelli, in a series of illustrations for The Divine Comedy, represented as an inverse cone. McCalls cone, unlike Naumans, does not refer to a metaphysical experience but to a geometrical-astronomical theme of Platonic origin: the circles derivation from the line and that of the cone from the circle. Circular movement is more perfect than rectilinear movement, which has no end. The simple body that changes into a circle is thus a perfect body. Within the nonspecific exhibition space, McCall organizes the construction of a body that is simultaneously geometrical and astral, redefining the conditions of classical projection to reset it, with its archaic connotations drawn from the physics of antiquity. Nevertheless, on noticing the space taken by the lights inscription, one realizes that Lines construction is impure. First, because some points of light are omit18. Chrissie Iles cites Naumans work without, however, referring to McCalls in the exhibition catalogue for Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art, 19641977 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2001), p. 65.

Line Light

17

ted within the circle as its tracing progresses, and second, because at the films end, at the point where the circles two halves join, they dont quite fit together. This imperfection of the tracing (due, according to McCall, only to strictly material conditions), although not essential to the intended purpose, has at least the effect of inscribing the circle within perception, of realizing it. Beyond its geometrical-cosmic construction, Line makes visible the real inscription of a form within matter. Solid Light means that the experience of light is an experience of a material sort, similar to those described by Lucretius on observing the movement of dust particles within a sun ray: Observe whenever the rays are let in and pour the sunlight through the dark chambers of houses; you will see many minute bodies in many ways through the apparent void mingle in the midst of the light of the rays, and as in never-ending conflict, skirmish and give battle, combating in troops and never halting, driven about in frequent meetings and partings . . . so that you may guess from this what it is for first beginnings of things to be ever tossing about in the

18

OCTOBER

great void . . . a small thing may give an illustration of great things and put you on the track of knowledge.19 The experience of projection is a physical, tactile one, in which the body, not only the gaze, is involved. Solicited to pass through the light ray and to remain within it, the spectator is activated; she becomes an actor. Through the physical experience of the light, she is transformed into fictioninto vision, as Plotinus would have it. In the Enneads, V.8 (On Intelligible Beauty), in his description of the beauty (over) there or (in) the land of souls and of the gods, Plotinus writes: For all there sheds radiance, and floods those that have found their way thither so that they too become beautiful: thus it will often happen that men climbing heights where the soil has taken a yellow glow will themselves appear so, borrowing color from the place on which they move.20 On entering the light ray, with his body suddenly snatched from the dark, the spectators faculties of viewing, vision, and the visible are conjoined, and this penetration of the silky, golden-brown web is not wholly without sensual connotations. In On Leaving the Movie Theater (1975), Roland Barthes stressed the erotic properties of the projections light ray, and one has the impression of reencountering, in his description of an ordinary film screening, the experience McCall tried to arouse in Line. In that opaque cube, one light: the film, the screen? Yes, of course. But also (especially?), visible and unperceived, that dancing cone which pierces the darkness like a laser beam. This beam is minted, according to the rotation of its particles, into changing figures; we turn our face toward the currency of a gleaming vibration whose imperious jet brushes our skull, glancing off someones hair, someones face. As in the old hypnotic experiments, we are fascinatedwithout seeing it head-on by this site, motionless and dancing.21 But why the eruption, in Barthes text, of this strange monetary metaphor, as seemingly incongruous as the cojones attached to Naumans cones? Probably because the light ray bathes the bodies and faces of the spectators, which are otherwise plunged in shadow, like Titians shower of gold falling upon Danaes body in a luminous shaft. McCalls film thus offers a singular response to the questions of matter, fixation, and transcription of light that traverse the history of art. The analytic

19. Lucretius, On the Nature of Things: De Rerum Natura, ed. and trans. Anthony M. Eselen (Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 1995), p. 60. 20. Plotinus, The Enneads, V.8, trans. Stephen MacKenna (New York: Larson Publications, 1992), p. 494. 21. Roland Barthes, Leaving the Movie Theater, in The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1986), p. 347; cited by Chrissie Iles, Into the Light, p. 45. The same erotic metaphor of projection appears in the opening pages of Jean Genets Pompes funbres (1947).

Line Light

19

reduction to its basic components of the cinematic setup in Line Describing a Cone is a fictive one; in the last analysis, it opens onto a mythological scenario. Apostil At the turn of the century, after twenty years of silence, when presentations of Solid Light Films were increasingly frequent in both the United States and in Europe, Anthony McCall inaugurated a new series of works produced not on film but digitally, since the computer facilitated the tracing of complex lines and the exploration of the plastic properties of curves. While the geometric pieces of the 1970s were based on a principle of equivalence between line and plane, from 2000 on, the post-geometric pieces played on the forms reversibility, on exchanges between interior and exterior, and the equivalence of horizontal and vertical vectors. At the same time, the adoption, from 2000 on, of mist-producing machines generated a texture both uniform and largerscaled, so that McCall was able to increase the scale of his pieces, conceived from then on as installations and projected in continuous cycles.

McCall. Doubling Back. 2003. Installation view, Muse de Rochechouart.

20

OCTOBER

McCall. Doubling Back. 2003. Installation drawings.

Doubling Back (2003), the first of this new series of films, based on a principle of equivalence between inner and outer surfaces, is made of two waves that slowly fuse and separate, in fifteen-minute cycles. Turning Under (2004) links the interaction of a wave and a plane of light to a rotary movement of ninety degrees. Between You and I (2006)along with its variation, You and I, Horizontal, McCalls most complex and monumental piece at that pointis composed of two adjacent vertical forms of solid light, each thirty feet high projected from ceiling to ground, and each formed from a traveling wave passing through a rotating plane of light and an elliptical cone in slow contraction and expansion. Gradually, each of the two light sculptures inverts its formal qualities so that it is transformed into the other. The transformation is realized using the Wipe, a conventional technique in feature films, no longer in frequent use, but given a new formal application in this work. However, the Wipe is ordinarily used for transitions from one sequence or shot to another and lasts only one or two seconds. In Between You and I, inordinately slowed down, it lasts sixteen minutes. The two shapes are never wholly visible in any given instant, but during the Wipe, that which is invisible within one form becomes visible in the other, so that at any given moment, everything is wholly present. In the chapter of The Analysis of Beauty that is devoted to line, William Hogarth proposed a consideration of the surfaces of objects as so many shells composed of lines closely stuck together. Such is the precise effect of Anthony

McCall. Between You and I. 2006. Installation view at Peer/The Round Chapel, London.

22

OCTOBER

McCall. Between You and I. 2006.

McCalls first geometric films: a production of surfaces through an arrangement of lines developing in time. When dealing with the waving linealso called the line of beauty or serpentine linethat appears to be formed by two contrasting curves, Hogarth says that because of its complexity, it cant be reproduced on paper without the assistance of the imagination or the help of a figure, and he chooses to represent it in the form of a fine wire properly twisted around the elegant and varied form of a cone.22 In his recent installations, with digital calculation replacing the work of the imagination, Anthony McCall intuitively rediscovers Hogarths lesson; his digitally drawn complex curves are logically deduced from his films of solid light done in the 1970s, just as, according to the eighteenth-century painter and theoretician, the serpentine line derives from the form of the cone. Translated from the French by Annette Michelson

22. William Hogarth, Of Lines, in The Analysis of Beauty (London: Oxford University Press, 1955), p. 55.

Identity Crisis: Experimental Film and Artistic Expansion*

JONATHAN WALLEY

The radical transformations that took place in the arts after the Second World War reached a crescendo in the 1960s. The nature and possibilities of each art form were fundamentally rethought, while the idea that these art forms could be clearly distinguished from one another gave way to intensive experimentation with cross-fertilization and mixing. Recall Allan Kaprows statement, The young artist of today need no longer say I am a painter, or I am a dancer. He is simply an artist.1 Or this definition by Joseph Kosuth: Being an artist now means to question the nature of art. If one is questioning the nature of painting, one cannot be questioning the nature of art . . . Thats because the word art is general and the word painting is specific. Painting is a kind of art. If you make paintings you are already accepting (not questioning) the nature of art.2 In the visual and performing arts, this period is described using terms like expanded arts, dematerialization, intermedia, and, more recently, the postmedium condition.3 The parallel term in film is expanded cinema. Put simply, it refers to cinema expanding beyond the bounds of traditional uses of celluloid film, the medium that had defined it for over six decades, to inhabit a wide range of other materials and forms.4

* This essay is dedicated to the memory of Adolfas Mekas. 1. Allan Kaprow, The Legacy of Jackson Pollock, Art News 57 (October 1958), p. 57. 2. Joseph Kosuth, Art After Philosophy, in Art After Philosophy and After: Collected Writings, 19661990, ed. Gabriele Cuercio (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991), p. 18. Art After Philosophy originally appeared in Studio International (October 1969), and Kosuth first made this statement in Arthur R. Rose, Four Interviews, Arts Magazine 43 (February 1969), p. 23. 3. The term is Rosalind Krausss. See Two Moments from the Post-Medium Condition, October 116 (Spring 2006), pp. 5562, and A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000). 4. I will use celluloid film to refer to all the physical components of the film medium taken together, as traditionally employed by filmmakers: camera, lenses, photochemical filmstrip, projector, and screen. I will use standard uses and traditional practices to refer to conventional filmmaking, as opposed to expanded-cinema practices in which the physical components of the film medium are multiplied, rearranged, replaced with other materials, abandoned, and/or used outside of the typical theatrical screening context. OCTOBER 137, Summer 2011, pp. 2350. 2011 October Magazine, Ltd. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

24

OCTOBER

As originally described by critics like Gene Youngblood and Sheldan Renan, expanded cinema included video and television, light shows, computer art, multimedia inst allat ion and per formance, kinet ic sculpture and theater, and holography, to name a few forms. It encompassed everything from mass-market theatrical films (Youngblood discusses Stanley Kubricks 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey) to experimental film (e.g., Michael Snows Wavelength and the films of Andy Warhol) to kinesthetic happenings and performances that employed no moving-image media whatsoever. As Youngblood had it, When we say expanded cinema we actually mean expanded consciousness . . . Expanded cinema isnt a movie at all: like life its a process of becoming, mans ongoing historical drive to manifest his consciousness outside of his mind, in front of his eyes.5 The expansion of cinema was often characterized as liberating filmmakers from tradition and convention. As Renan wrote in 1967, expanded cinema rejected the idea that motion pictures should be made to universal specifications on given machines under given and never changing conditions.6 Cinema was now liberated from the concept of standardization.7 Like Youngblood, Renan conceived of cinema in the broadest possible terms. Any material that could be used to control or manipulate light and timemetal, magnetic tape, plastic, glass, the human bodycould be a cinematic material. But if this liberation of cinema from the confines of the standard uses of celluloid film opened a door onto an exciting world of possibilities, it also raised concerns among filmmakers about the very identity of their art form. And it was specifically within experimental film that this expansion reverberated most forcefully, given that worlds proximity to (which is not to say its inclusion in) the art world. While many filmmakers and sympathetic critics felt some of the same skepticism toward traditional practices with media that animated the expanded arts in general, they must also have had reservations about the implications of cinemas expansion. A belief in and commitment to the specificity of film had been key to the assertion of cinemas autonomy within the pantheon of the arts and, as important, to experimental cinemas articulation of its identity as an artistic tradition. To cast off the film medium was to risk losing a connection to a tradition with which contemporaneous experimental filmmakers identified as artists and earlier generations had labored to build and nurture. That the exploration of new intermedia forms in the name of expanded cinema dovetailed with the sudden surge of interest in the moving image in the art world only complicated matters. As cinema expanded in the direction of other arts, these other arts reached toward cinema for a way to extend their major aesthet ic interest s, much as they had done in the 1920s. Together, the t win phenomena of expanded cinema and the proliferation of moving images in the

5. Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema (New York: E.P. Dutton and Co., 1970), p. 41. 6. Sheldon Renan, An Introduction to the American Underground Film (New York: E.P. Dutton and Co., 1967), p. 227. 7. Ibid., p. 227.

Identity Crisis

25

museum and gallery introduced cinema to new spaces and forms, and brought to bear upon it new discourses: expanded cinemas language of new media, intermedia, and synesthesia, on the one hand, and the art worlds post-Minimalist theorizing, on the other hand, wherein cinema became sculptural, performative, conceptual, and, in a more contemporary theoretical formulation, post-medium. An early expression of concern over these developments was Annette Michelsons critically important essay Film and the Radical Aspiration, first published in Film Culture in 1966. According to Michelson, the erasure of boundaries between the arts and the ethic of intermedia at the heart of expanded cinema threatened to derail radical filmmakings quest for autonomy and drain cinema of its potential power: The questioning of the values of formal autonomy has led to an attempted dissolution of distinctions or barriers between media. . . . Cinema, on the verge of winning the battle for the recognition of its specificityand every major filmmaker and critic in the last halfcentury has fought that battleis now engaged in a reconsideration of its aims. The Victor now questions his Victory. The emergence of new intermedia, the revival of the old dream of synesthesia, the cross-fertilization of dance, theater, and film . . . constitute a syndrome of that radicalisms crisis, both formal and social.8 In this essay, Michelson chastised certain experimental filmmakers for uncritically parroting the rhetoric of other art forms (for example, Brakhages association of his films with Abstract Expressionism, or action painting). Michelson acknowledged the possibilityindeed, the necessityof film drawing upon the other arts. But for artistic cross-fertilization to bear fruit, each of the interacting art forms needed to be secure in its respective ontologies.9 As the youngest art form, cinemaits sense of ontological identity still maturingwas the most susceptible to losing its independence by borrowing the forms and ideas of the other arts. Though Michelson did not make the point explicitly, one implication of her essay was that experimental cinema was especially at risk of losing its identity and independence in the context of cinemas expansion. It may indeed have been that every major filmmaker and critic in the last half-century had contributed to cinemas struggle for autonomy, but experimental film lacked the high-cultural profile and well-established economic and institutional infrastructures of more mainstream cinematic modes such as Hollywood cinema and the international art filmnot to mention the other arts. Moreover, experimental film was historically, aesthetically, and institutionally interconnected with the other arts in ways that

8. Annette Michelson, Film and the Radical Aspiration, in The Film Culture Reader, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000), p. 420. 9. Ibid., p. 420.

26

OCTOBER

Hollywood and the art cinema werent, making it more difficult to define against the backdrop of the media-focused expanded and inter-arts practices of the period. Michelsons essay, therefore, was an important intervention in that it saw the question of cinemas identity not solely in aesthetic terms but in institutional (i.e., economic) ones as well. As we shall see, her concerns were felt by filmmakers at the time, and remain relevant today. Expanded cinema and the embrace of the moving image by the art world thus threatened two intertwined endeavors undertaken by filmmakers and critics for decades: the definition of their art form and the establishment of its autonomy and therefore its worthamong the other arts. Once cinema stepped beyond the bounds of standard practices with the physical medium that had embodied it for over sixty years, how was it to be defined, or even recognized? If cinema could be made from so many other materials, what made the resulting forms distinct from those of the other arts? As it entered the gallery and museum, what, if anything, secured its status as cinematic as opposed to sculptural, painterly, or something in the gray zones in between? In short, if cinema could be anything, what was to prevent it from becoming nothing, from dissolving into the generalized mass of synesthetic intermedia art, the return of the Gesamtkunstwerk? The question was no longer what is cinema? but what isnt cinema? Thus, simultaneous with cinemas expansion was a concentrated program of medium-specific filmmaking in the form of Structural and Structural-materialist film; many filmmakers engaged in this kind of work had come to experimental cinema from the other arts, often continuing to produce work in these other mediums while making films that aggressively asserted the materiality of the celluloid-film medium and it s uniqueness. This paradox went to the root s of experimental cinema, which had, after all, begun with the cinematic experiments of avant-garde artists such as Fernand Lger, Hans Richter, Salvador Dali, Marcel Duchamp, Lszl Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, etc. The expansion of cinema, then, reanimated some of the fundamental questions and paradoxes of experimental cinemas history; these have continued to vex artists and scholars into the present day. Nearly ten years after Film and the Radical Aspiration, Michelson, in an essay on Paul Sharits, wondered about the nature and limits of Sharitss locational film works (gallery installations featuring film loops on multiple projectors) and their relationship to sculpture: that is, the ontological consequences attending films move into the gallery space.10 In 1984, well past the period of Structural and Structural-materialist films concentrated study of celluloid films specificity, the filmmaker Michael Mazire could still lament, Unfortunately experimental film often remains largely dependent on more established fine arts practices, unsure of its context.11 He concluded,

10. Annette Michelson, Paul Sharits and the Critique of Illusionism: an Introduction, Film Culture 6566 (1978), pp. 8789. 11. Michael Mazire, Towards a Specific Practice, in The Undercut Reader: Critical Writings on Artists Film and Video, ed. Michael Mazire and Nina Danino (London: Wallflower Press, 2002), p. 43.

Identity Crisis

27

The quest is still for a language which can describe, define, propose and question the issues at work [in experimental film] without being purely derivative of other practices, a space where new terms are engendered through, by and with a film practice confident of its specific independence.12 The last decade or so has seen a resurgence of critical interest in the issues raised by expanded cinema and the art worlds turn toward the moving image. The questions posed by earlier generations of artists and scholars seem all the more pressing and confusing today, surrounded as we are by a new surge of moving-image art in the gallery (by Matthew Barney, Shirin Neshat, Tacita Dean, Rodney Graham, and others) and the rapid proliferation of new media forms the spread of digital moving-image technology that is ushering in a new chapter of cinemas expansion. But once again, the difficulty of defining expanded cinema presents itself, as does the related problem of pinning down cinemas specificity within an ever-widening field. The place of experimental cinema, too, is still a question to be reckoned with. As Chrissie Iles noted in a talk at the Tate Moderns controversial conference on expanded cinema in 2008, the challenge of defining expanded cinema stems from fact that cinema itselfpre-expansion, as it werewas so heterogeneous that the label expanded seems redundant; the cinema, that is, was always already expanded. Iles thus offered a distinction between Expanded Cinema (capital E, capital C, as she put it), which had been a specific historical moment growing out of Structural and Structural-materialist film, and an ongoing expansion and contraction of the cinema that could be traced back to the pre-cinematic pastat least as far back as experiments with anamorphism during the Baroque period. Expanded Cinema (capitalized) was simply one momentif an especially rich and important onein the more generalized process by which cinemas ontology is always being redefined and re-historicized, a process that continues into the present moment of new, digital media.13 Iless phrase expansion and contraction speaks to a give-and-take between a radically expanded ontology that projects cinema across a multiplicity of forms and materials, on the one hand, and a narrower, medium-specific ontology that seeks to differentiate cinema from the other arts, on the other. Iless suggestive distinction, including her identification of a historically specific Expanded Cinema tied directly to the tradition of experimental cinema, is worth pursuing further. The increasingly unwieldy mass of forms and materials placed under the heading of expanded cinema has rendered the term, capitalized or not, bloated to the point of near meaninglessness. The all-encompassing generality of the term

12. Ibid., p. 44. 13. Chrissie Iles, Inside Out: Expanded Cinema and Its Relationship to the Gallery in the 1970s, (paper presented at Expanded Cinema: Activating the Space of Reception, Tate Modern, London, April 1719, 2009), http://www.rewind.ac.uk/expanded/Narrative/Tate_Doc_Session _2_-CI.html. (accessed May 9, 2011). The filmmaker Bradley Eros employs the same distinction between expanded and contracted cinema in There Will Be Projections in All Dimensions, Millennium Film Journal 43/44 (Summer/Fall 2005), p. 66.

28

OCTOBER

loses sight of all manner of specific practicesdistinct artistic currents that once flowed into expanded cinema and have since flowed out in new directions. For instance, it seems unlikely that most of the artists represented in Youngbloods landmark book Expanded Cinema thought of their work in terms of the cinematic. Instead, expanded cinema named a cluster of nascent art forms that have subsequently become more distinct: video art, media art and activism, performance art, moving-image installation, experimental and alternative television, kinetic art, light art, and the electronic arts and new media more generally (including the earliest stages of computer art and the precursors of Internet art). In the moment that all of these new media and forms were appearing, expanded cinema was a handy catchall for any work involving moving images, electronic media, light, time, etc. But it could only be a temporary designation; as time passed, these embryonic art forms specified their practices and developed their own histories defined by major artists and works, supporting institutions, and distinct critical languages and concepts. Moving-image work in the gallery, too, distinguished itself from cinema by invoking the language of the other arts, particularly the sculptural, a category that had radically expanded. That distinctionbetween the sculptural moving-image art of the gallery and the cinematic work of the theater (the white cube and the black box)remains with us today.14 Experimental Cinema (capital E, capital C, if you like) was distinguishing itself in much the same way during the same period. Though its history could be traced to the films of the European avant-garde of the 1920s, it only crystallized as a mode of film practice during the post-WWII period in places like New York, San Francisco, and London. This crystallization took place not only around key figures and dominant critical discourses but around institutions as well: co-ops, exhibition venues, journals, and structures of distribution and exhibition that continue to define the tradition. In short, experimental cinema was struggling for its identity and independence just like the other young artistic movements of the 1960s and 70sat the very moment when the preoccupation with intermedia and artistic expansion seized the art world. It might seem counterintuitive to subject expanded cinema to a categorization of the specific media and practices contained within it when it seems so manifestly about the subversion and disintegration of such categories. But a taxonomy of expanded cinema recognizes what the more generalized and accommodating conceptions cannot, such as the unique communities, critical vocabularies, and institutions that constitute the histories of, say, experimental cinema, video art, and alternative TV. Moreover, such a taxonomy does not require absolute, inflexible boundaries between art forms, nor does it need systematic notions of the specificity of each relevant medium (e.g., film, video), though it must recognize that the discourses of specificity and independence

14. For a discussion of this, see Jonathan Walley, Modes of Film Practice in the Avant-Garde, in Art and the Moving Image: A Critical Reader, ed. Tanya Leighton (London: Tate Publishing/Afterall, 2008), pp. 18299.

Identity Crisis

29

were certainly as significant to the art of the time as the ethic of expansion and boundary-breaking. In fact, the conception of expanded cinema I am proposing recognizes the interplay between generality (in which differences among art forms dissolve) and specificity (where each art forms distinctness and autonomy are asserted, explored, sustained): between expansion and contraction. * One way to address this distinction is in terms of the perceived relationship between the art of cinema and the medium of film. The assumption that cinema and film were identicalthe former an art form embodied in the latterwas the idea that expanded cinema countered. Medium-specificity, then, is understood as being directly opposed to the inter-arts generality of expanded cinema, an opposition mirrored in the other arts. Throughout its history, however, experimental cinema had produced morecomplicated meditations (in both theory and practice) on the nature of film and its relationship to the ontology of cinema. In this context, there were no simple distinctions between a medium-specific film practice and expanded conceptions of cinema. For example, the critic Deke Dusinberre suggested in 1975 that the materialist emphasis of European experimental cinema was leading in an unexpected direct ion: some filmmaker s, scrut inizing films mater ials in their investigations of cinemas fundamental principles, had produced work that abandoned the medium of celluloid film entirely. Dusinberre referred to Anthony McCalls Long Film for Ambient Light (1975), Tony Hills shadow performance Point Source (1973), and work by Valie Export and Peter Weibel. A paradox emerges, he wrote. The very emphasis on the material nature of the cinema . . . leads to immateriality.15 Expanded cinema and materialist filmmaking, seemingly two entirely opposite enterprises, were in fact interconnected. Looking back on this period from a contemporary perspective, Rosalind Krauss has argued that the medium-specific inclinations of experimental filmmakers in the 1960s produced a sophisticated ontological modelone that was suggestive to other artists: The rich satisfactions of thinking about films specificity at that juncture derived from the mediums aggregate condition, one that led a slightly later generation of theorists to define its support with the compound idea of the apparatusthe medium or support for film being neither the celluloid strip of the images, nor the camera that filmed them, nor the beam of light that relays them to the screen, nor that screen itself, but all of these taken together, including the audiences position caught

15. Deke Dusinberre, On Expanding Cinema, Studio International 190 (Nov.Dec. 1975), p. 224.

30

OCTOBER

between the source of the light behind it and the image projected before its eyes.16 In Krausss view, Structural films aim was one of producing the unity of this diversified support in a single, sustained experience.17 Krauss suggests that Structural filmmakers demonstrated the interdependency of their mediums component elements through the use of metaphors. For example, building upon Michelsons seminal phenomenological analysis of Michael Snows Wavelength (1967), Krauss interprets that film as an abstract spatial metaphor for films relation to time.18 This was a metaphor of pure horizontal thrust built out of the films famous forty-five-minute zoom-in, the illusory depth of the loft space, the suspense generated by the unfolding narrative action, and the slow rising of the sine wave on the soundtrack.19 This metaphor provided a unifying framework through which the viewer could apprehend the interdependence of the film mediums elements. Snows own comments on his film support Krausss apparatus-inflected interpretation: I was thinking of planning for a time monument in which the beauty and sadness of equivalence would be celebrated, thinking of trying to make a definitive statement of pure Film space and time, a balancing of illusion and fact, all about seeing. The space starts at the cameras (spectators) eye, is in the air, then is on the screen, then is within the screen (the mind).20 This conception of film as a network of interrelated components was far subtler than the reductive commonplace of modernist film criticism: that each Structural or Structural-materialist film was simply about the frame, or about flatness, or about flicker.21 As Snows comments suggest, Krausss itemization of the distinct yet interconnected components of film echoes a common tendency among experimental filmmakers and critics, particularly in the 1960s and 70s (and later in writing that makes reference to the films of that period). Attempts to isolate the

16. Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, pp. 2425. 17. Ibid., p. 25. 18. Ibid., p. 26. 19. Ibid. 20. Snow, quoted in P. Adams Sitney, Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 19431978, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), p. 375. 21. It should be noted that along with Michelson, P. Adams Sitney and Deke Dusinberre interpreted Snows film, and Structural film in general, in metaphorical terms of this sort. In both cases, the metaphoric interpretation counters the reductive, literal understanding of these films as being about nothing more than the film medium itself. Indeed, for Dusinberre, North American Structural films like Snows solved a problem that confronted European Structural-materialist film: that a purely reflexive, medium-specific aesthetic rendered films literally meaningless, unable to provide any further insight into . . . processes of cognition and comprehension, isolated in a closed circle of presence and self-reference. See P. Adams Sitney, Visionary Film, pp. 37880, and Deke Dusinberre, St. George in the Forest: The English Avant-Garde, Afterimage 6 (Summer 1976), pp. 1415.

Identity Crisis

31

medium-specific in film frequently produced laundry lists of films basic materials and physical properties. This tendency is perhaps best represented by David Jamess account of Structural film, which, he argues: variously emphasized the material nature of film and the separate stages of the production processfrom script, through editing and projection, to reception by the audience. Thus: flicker films . . . are about the optical effects of rapidly alternating monochromatic frames; Michael Snows Wavelength (1967), Back-Forth (1969) and La Region Centrale (1971) are about the effects of camera zoom, panning, and 360degree rotation; Barry Gersons films are about the ambiguous space between legibility and abstraction and thus draw attention to the dependence of representation on focus, framing, camera angle, and so forth. . . . And on through the list, it is possible to map out a periodic table of all structural films, all possible structural films, by positing a film constructed to manifest each moment in an atomized model of the entire cinematic process.22 The filmmaker Malcolm Le Grice mapped out just such a periodic table of Structural films, including films based on concerns which derive from the camera, concerns which derive from the editing process, concerns which derive from the physical nature of film, concern with duration as a concrete dimension, and concern with the semantics of image and with the construction of meaning through language systems.23 Paul Sharitss essay Words Per Page maps out an intensive study of film (a program of study he named cinematics) that ranged from emulsion grains and sprocket holes to processes of intending to make a film and processes of experiencing [a film].24 What is striking about these laundry lists of uniquely filmic elements is not how often such lists have been formulated, but how much they vary and how many different types of elements they incorporate, ranging from the resolutely material (emulsion grains, sprocket holes, the shutter) to the elusively ephemeral (light, time, ideas, and spectatorial experience). One might expect the itemization of film-specific elements to be a simpler matter: just list the parts of the film stock, camera, and projector, ident ifying these as the neutral mater ial ground upon which a medium-specific aesthetic can be based. But once a list of films specifics begins, it quickly proliferatesexpands, in factsuggesting, once more, that cinema is always already expanded. In doing so, these ontologies open up onto much more heterogeneous conceptions of cinema than one would anticipate from a medium-specific theory or practice. Sharits, for instance, closes his essay by stating, It may be that in

22. David James, Allegories of Cinema: American Film in the Sixties (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), p. 243. 23. Malcolm Le Grice, Thoughts on Recent Underground Film, Afterimage 4 (Autumn 1972), p. 83. 24. Paul Sharits, Words Per Page, Film Culture 6566 (1978), p. 37.

32

OCTOBER

limiting oneself to a passionate definition of an elemental, primary cinema, one may find it necessary to construct systems involving either no projector at all or more than one projector and more than one flat screen, and more than one volumetric space between them.25 And Jamess atomized model of the entire cinematic process slides seamlessly from cameras, lenses, flicker, and framing to a conceptual cinema, much like Bazins myth of total cinema, existing in a primordial state in the pre-cinematic period of Muybridge and Marey.26 Within the world of experimental film, then, there was no easy distinction between a medium-specific film practice and an expanded one, just as Dusinberre observed. The atomized conception of film provided the basis for a body of work that was expanded without losing its connection to the medium. Film, that is, was heterogeneous enoughinternally-differentiated, to use Krausss term.27 There could be an expanded cinema that was, at the same time, distinctly filmic. But where Krauss claims that the aim of Structural film was to unify the mediums component parts, the expanded work of filmmakers like Sharits signals a different path. Once film had been so atomized, filmmakers could intervene at any point in its table of elements; these elements could be multiplied (as in works that utilized multiple projectors and/or screens), rearranged, and/or replaced with alternative materials. Filmmakers could even abandon certain elements completely, the better to concentrate on the remaining ones, such as Sharitss systems involving . . . no projector at all, or Tony Conrads series of unprojectable film objects made by cooking, twisting, or hammering raw film stock. Rather than producing the unity of this diversified support, filmmakers working with this atomized model produced its disunity, dismantling the medium, breaking the interdependent elements of the apparatus apart and subjecting them to all manner of permutations to increase its diversity. Or, putting it a different way, it was the elemental conception of the film medium that unified these works, providing an abstract model that individual instances of expanded cinema could reference, even at many levels of remove. Indeed, the process could go as far as those filmless works by McCall and Hill that puzzled Dusinberre and referenced the physical medium conceptually or metaphorically. Hollis Framptons idea of the film machine is one version of this expanded ontology. Though he used the term in only one essay, For a Metahistory of Film: Commonplace Notes and Hypotheses, the idea reverberates through many of his other writings. In Framptons view, film could not be reduced to the celluloid strip, the camera, or the projector; it was, rather, the sum of all these things taken together: We are used to thinking of camera and projector as machines, but they are not. They are parts. The flexible filmstrip is as much a

25. 26. 27. Ibid., p. 43. James, Allegories of Cinema, p. 243. Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea, p. 30.

Identity Crisis

33

part of the film machine as the projectile is part of a firearm. . . . Since all the parts fit together, the sum of all film, all projectors, and all cameras in the world constitutes one machine.28 Defining film in this way allowed Frampton to imagine a filmmaking process that replaced or simply removed some of the parts without sacrificing the resulting works legibility as a film: If filmstrip and projector are parts of the same machine, then a film may be defined operationally as whatever will pass through a projector. The least thing that will do that is nothing at all. Such a film has been made. It is the only unique film in existence.29 The only unique film in existence to which Frampton referred was the composer Takehisa Kosugis performance piece Film and Film #4 (1965). In it, Kosugi made rectangular cuts of increasing size from a paper screen lit by the beam of an empty 16mm projector (starting with a small cut at the center of the screen and working his way out until there was, in effect, no screen left, and the projectors beam hit the rear wall of the space). Though it employed no celluloid, Film and Film #4 makes very clear references to the material conditions of filmmaking. Its alternations of white (the screen, the beam of light) and black (the darkened space, the growing hole in the screen), which Kosugi extended to the clothing he wore during the performance, invoke black-and-white photography, and positive and negative imagery. The alternations made to the screen suggest such filmic elements as framing, zooming, cutting (of course), and change over time. In Framptons 1968 Hunter College lecture, an empty projector runs while a text by Frampton on the nature of film plays on a tape recorder at the front of the screening space. During the lecture, the projectionist makes four films by inserting objects into the projector gate or by placing a hand or colored filter over the lens. It seems that a film is anything that may be put into a projector that will modulate the emerging beam of light, Frampton wrote, once again alluding to Kosugis piece.30 Al Wongs Moon Light (1984), a film installation with performer, employed an empty projector, moonlight, sunlight, and fire to fill the installation space with light and shadow. The performer used a mirrored disk to reflect light from the various sources around the space. Like Kosugi, Wong saw the interaction of light and shadow in filmic terms, as positive and negative imagery. Empty-projector performances like these represent one branch of a group of expanded works that collectively dismantle the film machine, displacing its compo28. Hollis Frampton, For a Metahistory of Film: Commonplace Notes and Hypotheses, in On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters: The Writings of Hollis Frampton, ed. Bruce Jenkins (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2009), p. 137. 29. Ibid. 30. Hollis Frampton, A Lecture, in On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters, p. 127.

34

OCTOBER

nents with substitute materials and actions. Here, celluloid film itself is replaced by another object that modulates the projector beam: the performer him/herself. The distinction between film production and exhibition is thereby collapsed, a move that was characteristic of much materialist film and expanded cinema of the same period (particularly in Europe). Such works conceive performance in essentially cinematic terms, making it a fundamental ontological element of cinema rather than an alien form (i.e., theater). In so doing, they place film into a position of parity with the rich and expansive field of performance-based art, but they also maintain an associative link with the materials of film and the inherently filmic aesthetic qualities or traits that medium-specific filmmaking favored. Another group of expanded-cinema works inverted the empty-projector performance, retaining the filmstrip but eliminating every other component of the film machine, frequently rendering the strip unprojectable and thus necessitating alternative modes of presentation. Among the best-known examples is the series of films that Conrad produced from 1973 to 1975, which he made by subjecting filmstrips to such processes as frying, roasting, hammering, and electrocuting, making them unprojectable. Sharits and Peter Kubelka created installation versions of their flicker films, including the formers Ray Gun Virus (1966) and the latters Arnulf Rainer (1960), in which the films were cut into strips of uniform length and mounted between Plexiglas. Conrad made a similar film object called Flicker Matte (1974), a mat (as in doormat or place mat) made by weaving together clear and opaque 16mm filmstrips, a joke on the flicker films he had produced in the previous decade. Takahiko Iimura has recently revisited a series of film installations he produced in the 1970s that were intended to reveal what he called the film-system.31 Like Frampton, Iimura conceived of film as the sum total of interrelated elements, which he put on display in installation form. In 2007, he issued a limited edition of twenty-four-frame (one second) strips of clear or opaque 16mm film spliced into tiny loops and encased in transparent plastic boxes. These film objects are exhibited in ways that call to mind painting (the Sharits and Kubelka films) or sculpture (Conrad and Iimura). But their makers consistently described them in the language of experimental-film culture, sometimes going so far as to explicitly distinguish them from other art forms. Conrad, for instance, saw his film objects as a logical endgame to the materialist practices of contemporaneous experimental film,32 as well as an attempt to liberate filmmakers from an unexamined reliance on (and therefore unwitting collusion with) the corporate manufacturers of film technology, such as Kodak.33 Employing nontemporal, sculptural forms, Conrad could radically extend the exploration of

31. Takahiko Iimura, On Film-Installation, Millennium Film Journal 2 (Spring 2002), pp. 7476. Also see Walley, Modes of Film Practice in the Avant-Garde, in Art and the Moving Image, p. 195. 32. Tony Conrad, Is This Penny Ante or a High Stakes Game? An Interventionist Approach to Experimental Filmmaking, Millennium Film Journal 43/44 (Summer/Fall 2005), pp. 103104. 33. See Conrads statement in a piece entitled Montage of Voices in Millennium Film Journal 16/17/18 (Fall/Winter 198687), pp. 25657, and Yellow Movies in Tony Conrad: Yellow Movies, a catalogue published by Galerie Daniel Buchholz and Greene Naftali Gallery, 2008, p. 22.

Identity Crisis

35

Takahiko Iimura. One Second Loop (=Infinity): A White Line in Black. 2007.

extreme duration that was characteristic of his work and that of many other experimental filmmakers of the period. Similarly, Iimuras film boxes, like the installations with which they are associated, invoke a duality that shaped the work of a number of other filmmakers, including Sharits and Frampton: that film is at once a static physical object and an ephemeral temporal experience. The loop, identified by Sitney as one of the four characteristics of Structural film, is a device that was used to extendsometimes indefinitelythe duration of experimental films and installations.34 But Iimuras loops are so small they cannot be projected, a playful expansion on the loops indeterminate temporality that turns them into non-temporal, static objects. The ephemerality of film in projection suggested by the reference to looping meets the physicality of film-as-object. Conrads film objects can be interpreted comically, as parodies of materialist filmmaking practices that play with notions of processing, chemistry, cutting, etc., humorously substituting domestic activities like cooking and weaving for con34. P. Adams Sitney, Visionary Film, p. 370.

36

OCTOBER

ventional production and postproduction processes. But all of these film objects are ironic, referencing the film machine and the conventional experience of film in projection precisely by subverting and stubbornly resisting them. In this way, such objects represent cinema at its most expanded and most contracted. They are material(ist) to the point of objecthood, a contraction of cinema to a single physical element. But this degree of contraction results in a form that could be called sculptural (hence expanding cinema beyond the bounds of its conventional format) or conceptual (inasmuch as they are artifacts that call to mind other processes and experiences not present in the works themselvesthose of the film machine). I will return to the notion of conceptual cinema, a phenomenon at the furthest reaches of cinemas expansion in the 1960s and 70s. To get there, however, requires looking at another variation of expanded cinemas dismantling or reorganization of the film machine: the replacement of the parts of that machine with alternative parts, a process of creative substitution that mobilized all sorts of other materials in the creation of cinema. Just as any of films elements could be removed, as in empty-projector performances or unprojectable film objects, or multiplied, as in works using multiple screens and projectors, they could also be swapped out for other materials. These materials become legible as cinematic via a metaphorical association with the specific film elements they replace, an association made possible by the overarching notion of the always already

Alan Berliner. Cine-Matrix. 1977.

Identity Crisis

37

expanded cinema: the heterogeneous, component ontology of film at large in experimental-film culture. Conrad and Alan Berliner both made variants of paper films (Berliners term, it is in part a reference to the means by which early films were registered with the Library of Congress) in the 1970s. 35 Conrads Yellow Movies series (197375) replaced both filmstrip and screen with a rectangular sheet of paper cut to proportions of 1.33:1 (the pre-widescreen Academy ratio) and painted with cheap commercial house paint. Conrad referred to the paint as emulsion and the paper sheets as both base and screen; he claimed that the slow photochemical changes that took place over decades, causing the white paint to turn yellow, constituted not only a production process but also each works running time. As a production professor at the University of Oklahoma from 1977 to 1979, Berliner, rather than making traditional projectable films, produced a series of cinematic works on paper, cardboard, and photographic scrolls. These include Cine-Matrix (1977), a grid of 156 images on pieces of cardboard, and Three Years (1978), a paper scroll made from three years worth of calendar pages tape-spliced end to end. I never stopped thinking of myself as a filmmaker, Berliner has said in reference to these works. And, looking back, I still believe that not making films in Oklahoma ultimately made me a better filmmaker.36 These works eliminate the need for a projector, but another strain of expanded cinema replaces the projector with specialized, nonstandard projection machines, usually fashioned by the filmmakers themselves. The best-known example of this is Ken Jacobss Nervous System, which Jacobs has used in live-projection performances since the early 1970s. The Nervous System is made from two synchronized 16mm analytic projectors fitted with a giant external shutter (like a whirling fan blade). The two projectors are loaded with identical film prints, aimed at the same spot on the screen (rather than side by side as in other multi-projector films), and run in synchronization, the external shutter alternately blocking the light of one and allowing the light from the other to pass. Jacobs loads each projector so that the two film prints are a few frames apart. This results in slight differences between the two images the projectors cast onto the screen. The rapid, flickering alternation of two slightly varied images creates a pronounced 3-D effect without the need for special glasses, a phenomenon Jacobs has explored further with his Nervous Magic Lantern, constructed in the early 1990s. Unlike the Nervous System, Nervous Magic Lantern performances utilize no film. Transparencies and objects are placed between a bright light source and an assortment of lenses, producing three-dimensional moving images with the aid of an external shutter similar to that of the Nervous System.37 As early as 1965, Jacobs began working with 3-D shadow play as a type of

35. See Scott MacDonalds interview with Berliner in his A Critical Cinema 5: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), pp. 15758. 36. Ibid., p. 157. 37. For further descriptions of the workings of the Nervous System and Nervous Magic Lantern (the latter of which Jacobs had previously been secretive about), see Optic Antics: The Cinema of Ken Jacobs, ed. Michele Pierson, David E. James, and Paul Arthur (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 273.

38

OCTOBER