Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Hirschprung Disease

Încărcat de

Jonathan ObañaDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Hirschprung Disease

Încărcat de

Jonathan ObañaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The most accepted theory of the cause of Hirschsprung is that there is a defect in the craniocaudal migration of neuroblasts originating

from the neural crest that occurs during the first 12 weeks of gestation. Defects in the differentiation of neuroblasts into ganglion cells and accelerated ganglion cell destruction within the intestine may also contribute to the disorder. [10] This lack of ganglion cells in the myenteric and submucosal plexus is well-documented in Hirschsprung's disease.[11] With Hirschsprung's disease, the segment lacking neurons (aganglionic) becomes constricted, causing the normal, proximal section of bowel to become distended with feces. This narrowing of the distal colon and the failure of relaxation in the aganglionic segment are thought to be caused by the lack of neurons containing nitric oxide synthase.[11] The equivalent disease in horses is Lethal white syndrome.[12]

Also known as Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon. It is the congenital absence of or arrested development of parasympathetic ganglion cells in the intestinal wall, usually in the distal colon. Symptoms are related to chronic intestinal obstruction and usually appear shortly after birth but may not be recognized until later in childhood or (rarely) in adulthood. The lack of colorectal innervation inhibits peristalsis, and the affected portion of intestine becomes spastic and contracted. The internal rectal sphincter fails to relax, which prevents evacuation of fecal material and gas and causes severe abdominal distention and constipation. The most common site affected is the rectosigmoid colon (short segment disease), and the less common is the upper descending colon and possibly the transverse colon are affected (long segment disease).

Assessment: 1. In the neonate:

No meconium passed Vomiting bile stained or fecal Abdominal distention Constipation occurs in all patients Overflow-type diarrhea Anorexia, poor feeding Temporary relief of symptoms with enema

2. Older child (symptoms not prominent at birth):

History of constipation at birth Distention of the abdomen progressive enlarging Thin abdominal wall with observable peristaltic activity

Constipation no fecal soiling, relieved temporarily with enema Stool appears ribbon like, fluid like, or in pellet form Failure to grow loss of subcutaneous fat; appears malnourished; perhaps has stunted growth Anemia

Best Answer - Chosen by Asker

Hirschprung's disease is a disease related to the intestines. Specifically, this disease is characterized by the loss of ganglion cells--nerve cells in the large intestine--in some parts of the large intestine, resulting in the non-movement of stool in the area without the nerve cells. This is much like the esophagus and the peristaltic movement, which is an involuntary movement. Take away the involuntary movement, and the food will more likely be stuck in our esophagus instead of the food going down. In the case of the large intestine, without such peristaltic action due to loss of ganglion cells, the stool gets lodged in one area, and as more stool is moved towards the end of the large intestine, the more the stool gets stuck, causing constipation. If unchecked and untreated, the patient may get an infection and/or die from chronic intestinal poisoning. This disease is considered to be a congenital one, even a prenatal one, since nerve cells differentiate during the stem cell differentiation stage. Non-formation of nerve cells in the intestines could have resulted from faulty cellular differentiation; the pathology of such an event is not completely clear, and genetic mutations could be implicated for the pathophysiology of this disease.

Definition o Enteric dysganglionosis condition See Also o Pediatric Constipation Epidiomology o Incidence: 1 in 5000 to 8,000 live births o Male to female ratio: 3:1 or 4:1 Causes o Genetic (Family History in 3-7% of cases) RET-proto-oncogene (Chromosome 10q11.2) related Associated with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia IIa Increased risk with affected sibling Boys with sibling affected: 3-5% Girls with sibling affected: 1% Cild's sibling with entire colon affected: >12% o Environmental factors o Intrauterine Intestinal Ischemia or infections Pathophysiology

Ganglion cells absent from part or all of the colon Lack of intramural Ganglionic cells Submucosa level (Meissner's Plexus) Myenteric level (Auerbach's Plexus) Aganglionic region begins at anus, extends proximally Distance proximal to Pectinate Line exceeds 4 cm Involved distal colon fails to relax Results in progressive Functional Constipation Congenital defect at 4-12 weeks gestation Neuroblast migration interrupted Ganglion cells fail to migrate via neural crest Lack of innervation Hypertonic bowel results in functional stenosis Partial or complete colonic obstruction Proximal Intestine markedly dilated with feces, gas

Types Short-segment Hirschprung's Disease Limited to rectosigmoid colon More mild than long segment disease Diagnosis may be delayed into early childhood o Long-segment Hirschprung's Disease Involves regions proximal to rectosigmoid In the most severe cases, may involve entire colon Associated Conditions o Bladder diveticulum o Congenital deafness o Cryptorchidism o Down's Syndrome o Hydrocephalus o Imperforate anus o Meckel's Diverticulum o Neuroblastoma o Primary Alveolar Hypoventilation (Ondine's Curse) o Renal agenesis o Ventricular Septal Defect o Waardenburg's Syndrome o Pheochromocytoma o Meningomyelocele Presentations: Age o Early: Newborn No meconium in 24-48 hours of birth (90% of cases) o First month of life Progressive abdominal distention Small caliber stools (pencil-thin) Infrequent, explosive Bowel Movements Failure to Thrive due to poor feeding

o

Bilious Emesis Jaundice o Two to three months of life Enterocolitis (fever, explosive bloody Diarrhea) Initial presentation in one third of patients o Older Childhood Chronic progressive Constipation Failure to Thrive or malnutrition Fecal Impaction Abdominal distention Recurrent despite enemas, Laxatives, feeding changes Presentation Patterns o Presentation soon after birth Complete Obstruction Emesis Failure to Pass Meconium in first 24 hours (90%) o Repeated Bowel Obstruction Emesis Dehydration Delayed meconium passage o Persistent mild Constipation Suddenly develops obstruction Distention Emesis o Diarrhea followed by obstruction Fever Enterocolitis o Persistent mild Constipation Never completely obstructs Signs o Distended Abdomen o Palpable loops of bowel o Rectal exam Tight anal sphincter Rectal exam without stool in ampulla Explosive release of feces and flatus may follow exam Imaging o Abdominal XRay Massive colon distention with gas and feces Air-fluid levels may be present Air in bowel wall suggests enterocolitis o Non-prepped Barium Enema Contraindicated if enterocolitis suspected False negative tests are common Dilated colon proximal to aganglionic region Spastic transitional segment

Irregular saw-toothed outline May be best seen on lateral view Barium may be retained in proximal bowel >24 hours

Diagnostics o Anal manometry Shows lack of internal anal sphincter relaxation Involves internal anal sphincter on rectal distention o Rectal suction biopsy (>1.5 cm above Dentate Line) Absence of Meissner, Auerbach's Ganglion plexuses Marked hypertrophy of nerve trunks Differential Diagnosis o See Neonatal Constipation Causes o See Failure to Pass Meconium o Functional Constipation Onset at over age 12 months Meconium passed in first 24 hours of life Normal growth Normal rectal exam Management o Pre-surgery maintenance Serial rectal irrigation decreases bowel distention o Surgery Mild to moderate cases (e.g. short-segment disease) Ilioanal pull-through anastomsis Severe cases (e.g. enterocolitis) Colostomy for 6 months and then ileoanal procedure o Post-Surgery Maintain high Dietary Fiber Monitor for enterocolitis despite surgery Complications o Untreated Bowel rupture Enterocolitis (up to 50% of cases) May occur 2-10 years after surgery o Post-Surgical Constipation (10%) Fecal Incontinence (1%) Prognosis o Early diagnosis results in best prognosis o Before surgery (without recognition and treatment) Mortality: 50% o After surgery Early complications: 30% Late complications: 39% Mortality: 2.4% Increased in Down's Syndrome

Increased in child under age 4 months Increased if postoperative obstruction Permanent ileostomy: 0.8% Permanent colostomy: 0.5%

References o Coran (2000) Am J Surg 180:382-7 o Kessman (2006) Am Fam Physician 74(8):1319-22 o Hussain (2002) Pediatr Clin North Am 49:27-51 o Worman (1995) Am Fam Physician 51(2):487-94

Pathophysiology

Congenital aganglionosis of the distal bowel defines Hirschsprung disease. Aganglionosis begins with the anus, which is always involved, and continues proximally for a variable distance. Both the myenteric (Auerbach) plexus and the submucosal (Meissner) plexus are absent, resulting in reduced bowel peristalsis and function. The precise mechanism underlying the development of Hirschsprung disease is unknown. Enteric ganglion cells are derived from the neural crest. During normal development, neuroblasts will be found in the small intestine by the 7th week of gestation and will reach the colon by the 12th week of gestation.[3] One possible etiology for Hirschsprung disease is a defect in the migration of these neuroblasts down their path to the distal intestine. Alternatively, normal migration may occur with a failure of neuroblasts to survive, proliferate, or differentiate in the distal aganglionic segment. Abnormal distribution in affected intestine of components required for neuronal growth and development, such as fibronectin, laminin, neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), and neurotrophic factors, may be responsible for this theory.[4, 5, 6] Additionally, the observation that the smooth muscle cells of aganglionic colon are electrically inactive when undergoing electrophysiologic studies also points to a myogenic component in the development of Hirschsprung disease.[7] Finally, abnormalities in the interstitial cells of Cajal, pacemaker cells connecting enteric nerves and intestinal smooth muscle, have also been postulated as an important contributing factor.[8, 9] Three neuronal plexus innervate the intestine: the submucosal (ie, Meissner) plexus, the intermuscular (ie, Auerbach) plexus, and the smaller mucosal plexus. All of these plexus are finely integrated and involved in all aspects of bowel function, including absorption, secretion, motility, and blood flow. Normal motility is primarily under the control of intrinsic neurons. Bowel function is adequate, despite a loss of extrinsic innervation. These ganglia control both contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle, with relaxation predominating. Extrinsic control is mainly through the cholinergic and adrenergic fibers. The cholinergic fibers cause contraction, and the adrenergic fibers mainly cause inhibition. In patients with Hirschsprung disease, ganglion cells are absent, leading to a marked increase in extrinsic intestinal innervation. The innervation of both the cholinergic system and the

adrenergic system is 2-3 times that of normal innervation. The adrenergic (excitatory) system is thought to predominate over the cholinergic (inhibitory) system, leading to an increase in smooth muscle tone. With the loss of the intrinsic enteric inhibitory nerves, the increased tone is unopposed and leads to an imbalance of smooth muscle contractility, uncoordinated peristalsis, and a functional obstruction.

Epidemiology

Frequency United States

Hirschsprung disease occurs at an approximate rate of 1 case per 5400-7200 newborns.

International

The exact worldwide frequency is unknown, although international studies have reported rates ranging from approximately 1 case per 1500 newborns to 1 case per 7000 newborns.[10, 11] Both So et al and Leon et al have studied the mutational spectrum of the disease in China.[12, 13]

Mortality/Morbidity

Approximately 20% of infants will have one or more associated abnormality involving the neurological, cardiovascular, urological, or gastrointestinal system.[14] Hirschsprung disease has been found to be associated with the following: o Down syndrome o Neurocristopathy syndromes o Waardenburg-Shah syndrome o Yemenite deaf-blind syndrome o Piebaldism o Goldberg-Shprintzen syndrome o Multiple endocrine neoplasia type II o Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome Untreated aganglionic megacolon in infancy may result in a mortality rate of as much as 80%. Operative mortality rates for any of the interventional procedures are very low. Even in cases of treated Hirschsprung disease, the mortality rate may be as high as 30% as a result of enterocolitis. Possible complications of surgery include anastomotic leak (5%), anastomotic stricture (5-10%), intestinal obstruction (5%), pelvic abscess (5%), and wound infection (10%). Long-term complications include ongoing obstructive symptoms, incontinence, chronic constipation, enterocolitis, and late mortality, mostly affecting patients with long-segment disease. Although many patients will encounter one or more of these problems postoperatively, long-term followup studies have shown that greater than 90% of most children experience significant improvement and will do relatively well.[15] Patients with an associated syndrome and those with long-segment disease have been found to have poorer outcomes.[16, 17, 18]

Race

Hirschsprung disease has no racial predilection.

Sex

Hirschsprung disease occurs more often in males than in females, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 4:1. However, with long-segment disease, the incidence increases in females.

Age

Hirschsprung disease is uncommon in premature infants.

The age at which Hirschsprung disease is diagnosed has progressively decreased over the past century. In the early 1900s, the median age at diagnosis was 2-3 years; from the 1950s to 1970s, the median age was 2-6 months. Currently, approximately 90% of patients with Hirschsprung disease are diagnosed in the newborn period

History

Approximately 10% of patients have a positive family history. This is more common in patients with longer segment disease. Hirschsprung disease should be considered in any newborn with delayed passage of meconium or in any child with a history of chronic constipation since birth. Other symptoms include bowel obstruction with bilious vomiting, abdominal distention, poor feeding, and failure to thrive. Prenatal ultrasound demonstrating bowel obstruction is rare, except in cases of total colonic involvement.[20] Older children with Hirschsprung disease have usually had chronic constipation since birth. They may also show evidence of poor weight gain. Older presentation is more common in breastfed infants who will typically develop constipation around the time of weaning. Despite significant constipation and abdominal distension, children with Hirschsprung disease rarely develop encopresis. In contrast, children with functional constipation or stool-withholding behaviors more commonly develop encopresis. About 10% of children may present with diarrhea caused by enterocolitis, which is thought to be related to stasis and bacterial overgrowth. This may progress to colonic perforation, causing life-threatening sepsis.[21] In a study of 259 consecutive patients, Menezes et al reported that 57% of patients presented with intestinal obstruction, 30% with constipation, 11% with enterocolitis, and 2% with intestinal perforation.[22]

Physical

Physical examination in the newborn period is usually not diagnostic, but it may reveal a distended abdomen and/or spasm of the anus. A low imperforate anus with a perineal opening may have a similar presentation to that of a patient with Hirschsprung disease. Careful physical examination differentiates the two. In older children, however, a distended abdomen resulting from an inability to release flatus is not uncommon.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hirschsprung's Disease: (Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon)Document16 paginiHirschsprung's Disease: (Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon)umiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hischsprug Disease by HamadDocument31 paginiHischsprug Disease by HamadALIEF MUTHIAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung Disease Case Study: Maecy P. Tarinay BSN 4-1Document5 paginiHirschsprung Disease Case Study: Maecy P. Tarinay BSN 4-1Maecy OdegaardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung DiseaseDocument44 paginiHirschsprung DiseaseAhmad Abu KushÎncă nu există evaluări

- Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon (Hirschsprung Disease) : Kristin N. Fiorino and Chris A. LiacourasDocument6 paginiCongenital Aganglionic Megacolon (Hirschsprung Disease) : Kristin N. Fiorino and Chris A. LiacourasSyakilla AuliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ILA - Hirschsprungs DiseaseDocument48 paginiILA - Hirschsprungs DiseaseSoleh Ramly100% (1)

- Hirschsprung's Disease PathophysiologyDocument8 paginiHirschsprung's Disease Pathophysiologyclaire yowsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschprung's DiseaseDocument26 paginiHirschprung's DiseaseAbdur RaqibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon - Hirschsprung Disease - 2009-6Document49 paginiCongenital Aganglionic Megacolon - Hirschsprung Disease - 2009-6Muhammad SubhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neonatal Intestinal Obstruction EPSGHAN PDFDocument77 paginiNeonatal Intestinal Obstruction EPSGHAN PDFRobert ChristevenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung 1socaDocument34 paginiHirschsprung 1socaDianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hisprung DiseaseDocument12 paginiHisprung DiseaseEky Madyaning NastitiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung DiseaseDocument25 paginiHirschsprung DiseaseMuhammad Zaniar RamadhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intussuseption and Hirschprung's DiseaseDocument5 paginiIntussuseption and Hirschprung's DiseaseAris Magallanes100% (2)

- GERD in ChildrenDocument31 paginiGERD in ChildrenSalman KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung Disease: Nadia Ismael Muse Safia Ahmed-Yassin SH: Ali Ilham Saed JirdeDocument24 paginiHirschsprung Disease: Nadia Ismael Muse Safia Ahmed-Yassin SH: Ali Ilham Saed Jirdesafia ahmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biliary atresia, Hirschsprung's disease, and anorectal malformationsDocument4 paginiBiliary atresia, Hirschsprung's disease, and anorectal malformationsMohamed Al-zichrawyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung DiseaseDocument20 paginiHirschsprung DiseaseIvy DanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constipation in ChildrenDocument34 paginiConstipation in Childrenabdisalaan hassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prune Belly SyndromeDocument39 paginiPrune Belly SyndromeHudaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirsch SprungDocument20 paginiHirsch SprungrisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intestinal Pathology III Hirschsprung'S Disease: DR Nzau MuangeDocument21 paginiIntestinal Pathology III Hirschsprung'S Disease: DR Nzau MuangeNzau MuangeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprun G'S Disease: Dr. Manish Kumar Gupta Assistant Professor Department of Paediatric Surgery AIIMS, RishikeshDocument48 paginiHirschsprun G'S Disease: Dr. Manish Kumar Gupta Assistant Professor Department of Paediatric Surgery AIIMS, RishikeshArchana Mahata100% (1)

- HirschprungDocument6 paginiHirschprungVanessa CasingalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung Disease: Waardenburg Syndrome Mowat-Wilson Syndrome Congenital Central Hypoventilation SyndromeDocument22 paginiHirschsprung Disease: Waardenburg Syndrome Mowat-Wilson Syndrome Congenital Central Hypoventilation SyndromeRizki Nandasari SulbahriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lec 1Document52 paginiLec 1zainabd1964Încă nu există evaluări

- Necrotizing EnterocolitisDocument36 paginiNecrotizing EnterocolitisMahad Maxamed AxmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 1 HirschprungDocument18 paginiLecture 1 HirschprungsharmeenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Congenital AnomaliesDocument10 paginiCongenital Anomaliesربيع ضياء ربيعÎncă nu există evaluări

- Askep HisprungDocument25 paginiAskep HisprungRika AmaliyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- No Bowel Output in NeonatesDocument24 paginiNo Bowel Output in NeonatesOTOH RAYA OMARÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung's Disease ExplainedDocument11 paginiHirschsprung's Disease ExplainedKarl JoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung DiseaseDocument17 paginiHirschsprung DiseaseJesselyn Heruela100% (1)

- Hirsch SprungDocument16 paginiHirsch SprungjessyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 12 - Paediatric Abdomen RadiologyDocument74 pagini12 - Paediatric Abdomen RadiologyMaria DoukaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intussusception PresentationDocument9 paginiIntussusception PresentationAme NasokiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ConstipationDocument33 paginiConstipationsalmawalidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung DiseaseDocument19 paginiHirschsprung DiseaseUgi Rahul100% (1)

- Chapter X.4. Intussusception: Case Based Pediatrics For Medical Students and ResidentsDocument5 paginiChapter X.4. Intussusception: Case Based Pediatrics For Medical Students and ResidentsNawaf Rahi AlshammariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Problem 4 Git: Ivan Michael (405090161)Document22 paginiProblem 4 Git: Ivan Michael (405090161)vnÎncă nu există evaluări

- 0327 Congenital Anomalies Rutter Congenital Anomalies Tracheoesophageal Fistula and Esophageal AtresiaDocument6 pagini0327 Congenital Anomalies Rutter Congenital Anomalies Tracheoesophageal Fistula and Esophageal AtresiaYvonne ChuehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung Disease (Aganglionic Megacolon)Document6 paginiHirschsprung Disease (Aganglionic Megacolon)Julliza Joy PandiÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEDIATRIC SURGERY PROBLEMSDocument141 paginiPEDIATRIC SURGERY PROBLEMSsedaka26100% (4)

- Hirschsprung Disease FarieDocument38 paginiHirschsprung Disease FarieFarie Farihan67% (3)

- Malformations of OesophagusDocument24 paginiMalformations of OesophagusOwoupele Ak-Gabriel100% (1)

- Pediatric Clinics of North America IIDocument54 paginiPediatric Clinics of North America IIkarenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Key signs and symptoms of infantile pyloric stenosisDocument6 paginiKey signs and symptoms of infantile pyloric stenosisNeil AlviarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung DiseaseDocument21 paginiHirschsprung DiseaseAhmad YaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gastric DisordersDocument135 paginiGastric DisordersEsmareldah Henry SirueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disorders of The IntestinesDocument64 paginiDisorders of The IntestinesCharmaine Torio PastorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung DiseaseDocument1 paginăHirschsprung DiseasePutri ClaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung'S Disease: DR: Jose Antonio Hernandez LivenDocument32 paginiHirschsprung'S Disease: DR: Jose Antonio Hernandez Livenmomodou s jallowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergencies in GITDocument7 paginiEmergencies in GITsssajiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirschsprung Disease: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment/TITLEDocument61 paginiHirschsprung Disease: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment/TITLEAdditi Satyal100% (1)

- Esophageal diseases and surgical managementDocument72 paginiEsophageal diseases and surgical managementBiniamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enfermedad de Hirschsprung: Diagnóstico Y Manejo en Niños Y AdultosDocument5 paginiEnfermedad de Hirschsprung: Diagnóstico Y Manejo en Niños Y AdultosAlexander Castillo CalderónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sick Growing Child: Hirschsprung Disease Anorectal Malformation Maluenda CamilleDocument46 paginiSick Growing Child: Hirschsprung Disease Anorectal Malformation Maluenda CamilleCamille Maluenda - TanÎncă nu există evaluări

- SG3 Paediatric Surgical EmergenciesDocument69 paginiSG3 Paediatric Surgical EmergenciesDiyana ZatyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dysphagia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsDe la EverandDysphagia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- PRC Form Cmo 14 IrishDocument6 paginiPRC Form Cmo 14 IrishJonathan ObañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mnemonic DeviceDocument12 paginiMnemonic DeviceJonathan ObañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessing pedal pulses in patients with hip fracturesDocument5 paginiAssessing pedal pulses in patients with hip fracturesJonathan ObañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistics and its role in data analysis, interpretation and decision makingDocument1 paginăStatistics and its role in data analysis, interpretation and decision makingJonathan ObañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alkylating AgentsDocument3 paginiAlkylating AgentsJonathan ObañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plan of ActivityDocument2 paginiPlan of ActivityJonathan ObañaÎncă nu există evaluări

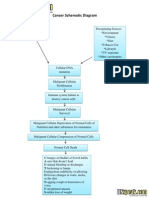

- Cancer Schematic DiagramDocument1 paginăCancer Schematic DiagramJonathan ObañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Herniated Nucleus PulposusDocument4 paginiHerniated Nucleus PulposusJonathan ObañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- In IvfusionDocument5 paginiIn IvfusionJonathan ObañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medifocus April 2007Document61 paginiMedifocus April 2007Pushpanjali Crosslay HospitalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1: Disability, Inequality, and InclusionDocument25 paginiModule 1: Disability, Inequality, and InclusionAuberon Jeleel OdoomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab Result - 742124389Document1 paginăLab Result - 742124389Shivanshu RajputÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tle ActivityDocument4 paginiTle ActivityManayam CatherineÎncă nu există evaluări

- FACULTY OF APPLIED SCIENCE BIO320 CASE STUDY: LEPTOSPIROSIS IN MALAYSIADocument12 paginiFACULTY OF APPLIED SCIENCE BIO320 CASE STUDY: LEPTOSPIROSIS IN MALAYSIAIlham Amni AmaninaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab Report: 2743025 LAB/20N/121831 27/jan/2022 Mr. Naman Thapliyal 13649512 StatusDocument2 paginiLab Report: 2743025 LAB/20N/121831 27/jan/2022 Mr. Naman Thapliyal 13649512 StatusM Abdul MoidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Purified Used Cooking Oil Through SedimentationDocument4 paginiPurified Used Cooking Oil Through SedimentationJan Elison NatividadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory TestDocument26 paginiMinnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory TestGicu BelicuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Establishing Positive Family Relationships for Health PromotionDocument78 paginiEstablishing Positive Family Relationships for Health PromotionsunielgowdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digital Rectal ExaminationDocument7 paginiDigital Rectal ExaminationAla'a Emerald AguamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ovitrelle Epar Medicine Overview - enDocument3 paginiOvitrelle Epar Medicine Overview - enPhysics with V SagarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Safety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance / Preparation and of The Company / UndertakingDocument3 paginiSafety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance / Preparation and of The Company / UndertakingnbagarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vdoc - Pub End of Life Care in Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument251 paginiVdoc - Pub End of Life Care in Cardiovascular Diseasericardo valtierra diaz infanteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vaccination Program in Farm AnimalDocument87 paginiVaccination Program in Farm AnimalThành Đỗ MinhÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4th Yr SingiDocument322 pagini4th Yr SingiSthuti Shetwal100% (1)

- The Nature and Meaning of Physical EducationDocument14 paginiThe Nature and Meaning of Physical EducationRegie Mark MansigueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soal Lokasi KIK - 2Document2 paginiSoal Lokasi KIK - 2novida nainggolanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aunt Minnie Pediatric NeuroDocument15 paginiAunt Minnie Pediatric NeuroRommel OliverasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Small-Scale Mining To The ResidentsDocument15 paginiImpact of Small-Scale Mining To The ResidentsAngelIgualdoSagapiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Examination: History: by Professor of Internal MedicineDocument47 paginiPatient Examination: History: by Professor of Internal MedicineMonqith YousifÎncă nu există evaluări

- ANM application detailsDocument3 paginiANM application detailsSOFIKUL HUUSAINÎncă nu există evaluări

- Southampton Grading SystemDocument5 paginiSouthampton Grading SystemswestyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Herboboost Capsules: Kutki, Chandan)Document3 paginiHerboboost Capsules: Kutki, Chandan)Snehal AshtekarÎncă nu există evaluări

- CMC Vellore Summer Admission Bulletin 2020 Revised 16 Nov 2020Document58 paginiCMC Vellore Summer Admission Bulletin 2020 Revised 16 Nov 2020Allen ChrysoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peginesatide For Anemia in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease Not Receiving DialysisDocument21 paginiPeginesatide For Anemia in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease Not Receiving DialysisEdi Kurnawan TjhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Drug Abuse on Health and SocietyDocument9 paginiEffects of Drug Abuse on Health and SocietyAditya guptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- E-Learning PHARM 131 - Chapter2Document10 paginiE-Learning PHARM 131 - Chapter2Ryan Charles Uminga GalizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winters Ildp Final Review Draft ApprovedDocument7 paginiWinters Ildp Final Review Draft Approvedapi-424954609Încă nu există evaluări

- PNLE June 2007 With Key AnswersDocument82 paginiPNLE June 2007 With Key AnswersJustin CubillasÎncă nu există evaluări

- LastCallProgram ScienceDocument16 paginiLastCallProgram ScienceConiforÎncă nu există evaluări