Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Neruda's Fragmentation of Love in Twenty Poems

Încărcat de

RantikDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Neruda's Fragmentation of Love in Twenty Poems

Încărcat de

RantikDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The discourse of desire and the fragmentation of the beloved in Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair

Abstract: Veinte poemas de amor y una cancin desesperada by Pablo Neruda is a notable example of the Petrarchan technique of fragmentation and depersonalization of the woman. In effect, in some poems the beloved is body or one of its parts; in others, on the other hand, she is transformed into a memory, longing, beret, port or word. The purpose of this textual dissection is to establish a discourse of desire that transforms the woman into an object possessed or used as an instrument. The beloved, in this framework, more than a representation of a human being made of flesh and blood, is a literary mirror where the poetic voice reflects itself in order to contemplate its doubts, aspirations, and desires. This practice, despite its aesthetic value, perpetuates stereotypes associated with the woman described and/or constructed according to the interests of a patriarchal culture. Key Words: beloved, dissection, fragmentation, poetry, Pablo Neruda.

2 The discourse of desire and the fragmentation of the beloved in Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair

Love and passion are privileged topics in poetry. Love, in particular, and its innumerable variants dominate the literature of west. Almost all the writers of this tradition address the theme by introducing images that go from one extreme to the other: idealize or decry the loved. In effect, their representation ambiguous and contradictory distorts their image and, additionally, the relationship between lovers. The woman, in this theme, more than a reflection of a being of flesh and blood, is a literary mirror where the author reflects himself to contemplate his doubts, aspirations, and desires. This practice, despite its aesthetic value, perpetuates stereotypes associated to the woman described and/or armed according to masculine interests. Sigmund Freud advised that: For distinguishing between male and female in mental life we make use of what is obviously an inadequate empirical and conventional equation: we call everything that is strong and active male, and everything that is weak and passive female (188). The power and danger of this radical conventional equation is that the majority of people tend to believe that it was established by nature or by some other plan greater than the conventions promoted by the patriarchal culture. In this essay I propose that the representation of the beloved in Twenty Poems of Love and a Song of Despair by Pablo Neruda is ambiguous and distorted because the explanation from her body or some of it parts privileges the masculine desire of poetic voice. The relationship between a man and woman is constructed from a point of view that favors the masculine domination over the feminine: he is the subject and she is the object. In this theme the beloved suffers a process of dissection that removes her identity as a person to convert her into a

3 woman-instrument that generates, in addition to desire, silence, melancholy, absence, and poetry. Pablo

PAGINA 2 Neruda, however, was not the first to fragment and literally objectify a lady. The strategy is so old that it is confused with initial literatures. It was Petrarch, however, who had more success. And not just in fragments, but to transform his beloved in the feminine ideal of beauty: Laura, the muse of the Canzoniere, is the canonical source of the image of women in the arts of the Renaissance. In the poetical work of Petrarch the feminine portrait is formed by means of a fragmentary enunciation and ambiguous of certain psychosomatic characteristics. In effect, Laura the object of Petrarchan love is a collection of eyes, hair, hands and feet. Imprecise representation and distortion set the ideal woman as not happening to be a collection of pieces without identity. This method to dismember the female bofy and to compare the parts to elements of nature has been very imitated an parodied for authors of the Hispanic world, especially in the Renaissance and Golden Age sonnets that abound in these types of descriptions. In Latin America Twenty Poems of Love and a Desperate Song is a notable example of the technique to fragment and to (de)personify the woman. This bunch of poems, the most famous book of Pablo Neruda Book of Masses according to Salam (24) has raised a number of critical exegeses. It is my postulation that the female, an indispensible premise of the theme of love, has an inescapable presence in Twenty Poems, but this revelation is ambiguous and, therefore, contradictory. In some compositions the beloved is the body or

4 some of their parts (eyes, hair, breasts, hands); in others, instead, were transformed in memory, nostalgia, beret, port, or word. In general, it is observed that the physical the concrete - the poet enumerates abstract characteristics that denote the feminine subject as a person. This textual dissection includes two aspects: (de)composition in a series

PAGINA 3 of features y the metaphoric allusion in nature. In poem 1, for example, the beloved is the species Gea that assumes the form of one: Body of a woman, white hills, white thighs (47); and when the poetic speaker is more specific, this is the Body of skin, of moss, of milk hungry and firm. Oh the vessels of the chest! Oh the eyes of absence! Oh the roses of the pubis! Oh your light slow and sad (47). The second poem, perhaps the most ambiguous and secretive of the work, presents to one to be cosmic most abstract that the first text --womannight according to Goic--. But as well as speaking of the soul of the friend the modern version of the enemy Petrarchanthat, incidentally, is dumb, the adjective problematic because it gave the impression of one dummy which were then dark clothing without describing any faction except one faction with their mouth shut. Poem 3 mentions a doll with eyes, waste of fog y arms of transparent stone (55). Fog and stone are opposite elements, but its attributes instabilities and permanenceare physical properties of the beloved: the struggle between the concrete and the intangible, the illusion of the feminine body. Poem 4 is the one exception: there are no references to a woman of meat and bone (ie. flesh and blood); exists, instead, one of the few mentions of the couple in the community: Innumerable heart of the wind/ beating on our loving silence (59; my emphasis). The

5 apparent reciprocity of sentimental loving, however, its relegated to highlight the action of one strong wind.: nature in more important than lovers. In poem 5 the women is reduced to hands smooth as grapes (63); while in poem 6 is evoked as a gray wool hat(beret), a voice of a bird and heart of a home (67), features that en the context of this attempt, the dehumanizing in oder to identify elements of the home for the lover: the women as a refuge. Poem 7 alludes to the ocean eyes of the the lover. New: eyes, arms, and her breasts are described in poem where the poetic

PAGINA 4 slid in an imperative sentence that reifies to the lady: Ah bare yout body, a frightened statue (75). Poem 9 is limited to speaking of the parallel body of the woman. The pair of lovers reappear in poem 10 through some hand in hand; the beloved, nonetheless, is remembered saying words: a species of echo that repeats the yearning and/or desires of the poetic voice. The rest of the book is not very different. In poem 11 Neruda returns to identify the little girl with Gaia: it was made of all things (87). In poem 12 he mentions the chest, the soul, the absence, and the song of the dear being aside of comparing it with an old road. In poem 13 the feminine body is the geographic species where the masculine eroticism engraves its discourse of the desire: the white atlas of your body (95). Nevertheless, from poem 14 appears a recollection more obtained from the woman, it is ambiguous and not very developed: You are more than this white head that binds you (99) says the bard and the eyes reappear, the breasts smell and the mouth of plum. Poem 15 emphasizesand celebrates the feminine silence, moreover of the flown eyes, and the closed mouth: a humanized

6 statue. Poem 16 compares the woman with a cloud and mentions its lips, feet, and eyes of mourning. Poem 17 evokes a you enigma and stresses its strange and odd presence to the bard that fails in his attempt to communicate and reveal the feminine mystery:11 []Who are you, who are you? (112) is the desperate question that goes unanswered.12 Although in poem 18 the poetic speaker confesses his love, of the only beloved notes a part of her body: the eyes. Poem 19 celebrates the sun as creator of the woman; but not even the sun is exempt from falling apart since, according to Neruda: does your beautiful body, your shining eyes, and your mouth that has the smile of water (119). Poem 20 praises the great still eyes of the dear being. Remember, also: her voice, her bright body. Her infinite eyes (124). For

PAGINA 5 last, The Desperate Song is more emphatic in fragment to the female remembered in her condition of flesh loved and lost: Oh flesh, my flesh, woman that loved and lost, (128). It mentions, also of arms, a bite mouth, kissed limbs and, --debatable affirmation--, it alludes to the woman with an eschatological phrase: pit of debris. The quotes are conclusive: the Twenty Poems of Love and a Desperate Song are butchered to be loved. Which is, however, the purpose of this textual dissection? Consider that there are various answers. I pointed out the obvious: the dismemberment of the woman founded a discourse of desire that transforms it into an object of contemplation and fetishization, obvious aspect by the celebration of her physical attributes in a species of poetic close-up of certain parts of her body. In any of these functions the result is the same: the objectification of the woman in order to instrumentalize and possess her better. Following this approach, the feminine body is the leisure site where the masculine lover prints his mark

7 and utilizes it depending on his expectations (satisfaction of necessities, especially sexual and erotic through literary evocation). To begin, in the poem that starts the series, the adolescent Nerudian I tells the history of his life in opposition to the rest of the world. The poetic speaker is the misunderstood that repels all, with the exception of his lady, shelter and mediator between the world and the young, grim and lonely lover. The attitude of the poet is clear: to instrumentalize the woman. Also of being a sexual object suitable for the procreation: My savage body of a laborer digs in you and makes the son leap from the depths of the earth (47), the woman is built as a sexual object body, thighs, chest, and pubis without identity. The analysis of Pacheco Acua of this poem summarizes these points: This drastic change of conventional imagery made some critics affirm that Neruda was not celebrating love but sex. However, I think this poem is not only a celebration of the

PAGINA 6 deleites sensuales de la carne, pero tambin un ejemplo de la ausencia de la identidad femenina (32). It must be added to this correction that, in agreement to the poet, the loved one is also a weapon, a defense mechanism, say, the instrument to protect oneself from the world and from oneself: For me to survive forge yourself as a weapon, like an arrow in my bow, like a stone in my slingshot (47).17 I think that these verses reveal one of the obscure topics of poetry: the fate of various lovers.18 This polygamist fantasy is only possible possible for forging a passive woman whose parts attract and satisfy the erotic desire without feminizing the male lover that already, such that Barthes suggests, reduced the autonomy of the male to bring it closer to the lover, whom, at his time, made love possible. At the same time, through her supposedly social role of reproducing the species, creating life,

8 and providing security, the female is associated with the archetypal image of Gea that on one hand resolves the analogical problem identifying woman with nature ,19 that deepens the ignorance of that instance or, at the least, her partial apprehension with the consequent dissatisfaction with the male lover. In effect, the female body, reproducer and protector, fails to quench the thirst, the longings, the fatigue, and the pain of the poetic self: Body of my woman, persist in your grace. My thirst, my longing without limit, my indecisive chase! Dark beds where the eternal thirst follows, and the fatigue follows, and the infinite pain. (47) The possessed (utilized) body of the woman cannot satisfy the demands of the lover so singular that demand all to change from dissatisfaction, fatigue, and infinite pain. It weighs open the perceived limitations of this space of flesh that one enters,20 the poetic voice continues

PAGINA 7 Holding on to this; astonishingly persistent that she resorts to the poem 3 where her lips anchor and her anxiety dwelled in her feminine body transformed in port and nest, places of excellence to give refuge. The topic of the woman, to give refuge again in the poems 6 and 12. In poem six, furthermore of beret , synecdoche allusion in order that an object stands in for a part of the body that, at some time, explains all, the feminine territory is the safe place (heart and house) of where they speak of the profound wishes of the poet: the white of the masculine arrows of poem 3. In poem 12, the chest of the lady is the space that can contain the heart of the lover: a kind of box that guards the jewel of the masculine love.

9 Likewise, say that the women is warm like an old road and is populated of [] echoes and nostalgic voices (91). These examples show that the search for protection en the feminine geography is constant, the same that the physical needs of the poet that cant conceive the universe without taking possession of her sweetheart or, the lesser thing, to territorialize her, that is to say, to award her quality of territory to hold the masculine domain. Object of possession and lyrical feelings, the women is the place that justifies the discourse of the wish of the lover. There isnt that to lose sight, nevertheless, that the woman is present like object and absent in so much subject. The poem 13 goes into greater detail of the body association; space eluded to the feminine white atlas an unknown land where the male mark their territory with crosses of fire. The women, in so much map of beauty, are object of possession and reason of exploration, modification, and construction. Thats the thing recognized one of their most enthusiastic critics: Neruda doesnt only express her love to the loved woman. She doesnt only surrender admiration and burn in the incense of her best words, also describes the woman, she describes the physical beauty, little by little, like a passionate cartographer, and she is going to construct the map of those bodies.

PAGINA 8

divine" (Meneses 101). It is about very suggestive imagery: the conquistador, this time armed with a feather, taken from a continent until then unexplored. The male presence marks, opens, penetrates and undermines a virgin land (flesh) whose passivity gives sense and validity to the action of the possessive lover. It is not strange, therefore, that the male is

10 always in movement in the white atlas and motionless in the feminine absence. Poem 7 corroborates this interpretation. Here the lover tries to look for and/or get over falling into the clutches of the oceanic eyes of the woman (71). But the possession of the feminine space is not possible because her eyes contain the waters of mystery, the unexplored place and impossible to control; and, for that reason, the dangerous place that threatens to drown the loneliness of the poet, a metaphorical reference that alludes to intimacy and the male desires. In the face of failure to own this marine territory, the conclusion of the bard is negative. Nothing good can come of the beloved woman. Distant or close, this isfollowing a feminist readingdegraded and clear in terms of absence, obscurity and horror: You only guard darkness, my distant woman in your look emerges the coast of the horror at times (71). Neither is it irrelevant to point out that the males love is intermittent in this composition, sometimes yes and sometimes no; insecurity synthesizes by the two magnificent verses: The night birds peck the first stars that twinkle like my soul when I love you (71). In poem 14 the objectivized woman reappears and available in her generative role thanks to the wish of the bard: I want to do with you what the spring does with the cherry trees (100). Here the female has a double function. First, she stresses her passive role, a land that waits for the masculine seed in order to flower and give fruit. Second, her body is a thing for exclusion: an abstract space, the theater where the representation takes place

PAGINA 9 erotic. These verses can be interpreted as self-praise of procreative manly power because it renews the nature of propagating the species: the victory between death. The beloved is too, by the work of the lover, nature is in this poem. But this type of versesphallic

11 dismembers, penetrates, possesses, and annuls the active category of feminine identity. The words, by the instrumentation of the human body, are not a medium of communication, but a form of approach and knowledge to conquer, to win, to possess, and to take refuge in the female emphasizing its natural function to feed material and spiritually (poem 2): You are mine, you are mine, woman of sweet lips,/ and my infinite dreams live in your life says, to cite another example, poem 16. But perhaps poem 15 is the best illustration of the process of making the lady inanimate. In that composition the belovedpassivity makes the personis dumb, but not deaf: she lives to listen to poetry. The stereotype of women as consumers of poetry is also notorious in poem 5: For you to hear me My words Become thin sometimes Like the seagulls on the beach This passage is conflicting because it raises a problem in communication. It implies, in the first line, the intellectual complexity of the primary message of loving and understanding not by the beloved. So it is important that the words transform, receptive to conform to the level of symbolic characteristics similar to the prints of marine birds. Male knowledge and female nature are faced in this text. Something similar occurs in poem 15 where the man sends subtle messages and the woman

PAGINA 10

12 She was quiet it seemed that she did not understand: [] and my voice does not affect you. This lady, additionally, she did only not talk, not only was her silence the quality for excellence that satisfies the poet: I like when you are quiet because you are distracted, Since you hear me from a distance, and my voice does not affect you. It seems that if your eyes had the ability to fly it seems that a kiss would close your mouth. (103) It is heavy of the kiss that imposes silence--or such time for this--, the beloved, distant and painful, is to put to death, to the soul of the poet and to the melancholy word. One more time the lady I held did not pass to look like something privileged for the poetic voice, not personified, until true degree, she sums up the attitude of the loving I start if I was a womeninstrument that generates silence, melancholy and absent. Silence that possibly has to hear the voice of the poet, absent that she woke up the inspiration and melancholy that justifies the love and the masculine happiness, strokes that also they observe in my celebration and always in anthology poem 20. In this text the women-device she produces sadness, uneasiness, and poetry: I am able to write the sadder verses this night (123). Another fact that she instruments is she loves and she feels left out to the traditional role of the muse--to inspire verses--is the verification in that her beauty is unachievable in the moment of the invocation (lost love). This that she provokes that I am poetic to be anguished and I was consoled with the remembrance of one possessed in a past time of, the paradoxical form, I would deny and affirm the love of the present time: Already I do not want it, it is true, but such time I want her (124). It is not possible to perfectly comprehend the heartfelt paradoxical feeling of this verse. For me, he expresses a denial that she affirms: he denies the woman affirms the love.

13 The fragmentation of the women in Twenty poems, and the intention to object her and instrument her, is observable in the majority of the compositions of the book. But The

PAGINA 11 Desperate Song even though it seems to negate the combining of these topics. First, the exception that confirms the rule: in this poem of the abandoned, one encounters one of the scarce references to the pair in mutual interrelation: Oh, the crazy conjunction of hope and effort/in that we tie and despair (128). Despite no active interaction between the lovers, failure is the destiny of both. It seems that in this text, beyond sex, there isnt possible communication; whats more, the consummation of desire separates them; they are aliens to one another. Another part, the failure, experienced by the distance and the remoteness, determines that the poetic voice alludes to the lover with a carnal obsession; love and loss, is to say, an instrument that had usefulness for a moment to satisfy their physical needs. As to the sorrow of that the instance already was, the love in reality their memory still has spiritual usefulness; it produces an eroticism both anguished and melancholy. In effect, the poem seems to find happiness in a sort of erotic desperation. If this was acceptable, the eroticism of the absence is a method of rapprochement to the yearning body and/or desire; a technique to accept and neutralize the past and space presents through the word that establishes to the other feminine ones because it defines such who senses it, and finds and makes possible their absent presence. It notes, in addition, a self-complacent distancing that doesnt decide: Oh! Is it an exclamation of shame or joy? Whatever that was the solution, the tools dont change as soon as the mechanism of self-gratification and defense against the world. Octavio Paz summarizes this point more clearly: The distance breeds the erotic

14 imagination. The eroticism is imaginary; it is a shot of the imagination, front to the outside world (I. Pan, eros, psique 47). And now, the confirmation of the rule: the loved of The Desperate Song produces a process of self-reflection in the poem; whose conclusion is negative: all in you is

PAGINA 12 failure. This inadequate woman, as much an individual - a memorable unit - , is useless for the dissected practice: she is meat, declares the poetic voice and seems to suggest that she is nothing because the final product of an affair is dissatisfaction and despair, the illusions of eroticism. On the other hand, it is interesting to note that a woman in actuality her arms is the refuge of the poet, the fruit that satisfies his hunger and thirst for love and; above all, the miracle that overcomes the pain and ruins of a somber existence. Yes, but she is also another less pleasant place: a cemetery of kisses the final refuge of the poet? and a biting mouth: lips consumed with violence. From this I estimate that the affair is forced even when the lovers depend, up to a point, on each other. The difference stems from the fact that the lover is compared to an object of material and spiritual consumption, and not as one of flesh and bone with free will. In effect, the woman, as is seen in other poems, is mute, silent, distant or a body almost lifeless that the masculine poet has to arouse, think of, and remember. A lover, in short, made of memory and oblivion. But the memory cannot revive the past. At the most feminine things are believed to be fragmenting, strategy that justifies the masculine necessities every time the unity of the man uses the feminine part that he was attracted to and married for. The dissection and instrumentalization, therefore, fund the speech of desires. It is not difficult, in this scheme, to infer that the female body is the territory, the

15 blank atlas where patriarchal culture writes its fantasies and obsessions; its silence, passiveness, and fragmentation make it possible for man to be the creator of feeling and importance. And, nevertheless, a great nostalgia affects the writing of Nerudiano: the nostalgia of the body, not fragmented, but complete. Using as a premise the previous conclusion, I believe that in Veinte Poemas there does not exist a convincing representation of love, a feeling that combines two free wills in order to

PAGINA 13 to elect. That which is a sexual feeling and an eroticism of the nostalgia that, for the contemplative distance, excludes the feminine, at least in their active role in so much as individual because like nature the woman is very active. According to this interpretation, the loved one is trapped because of melancholy verses that they chopped up for reasons best unknown. The masculine poetic voice, in large measurements for the feeling of loss and alienation, denies the freedom of the woman, an aspect that since then unauthenticated the presence of love. Lacks, criticizes Salama, spiritual contact. Without seizure, the

eroticism of the nostalgia is not a feature of everything negative; on the contrary, it is also to marvel, sometimes of a distressing manner - Who are you, who are you? before that unknown so close and so far: the loved one absent but present. The absence of the feminine presence leads me to propose that the poetic voice loves an abstract idea and not a person: imagination. If you accept that, one more time you conclude that love does not exist in Twenty Poems: only eroticism and sexuality, such which appears to emphasize the poem 1 or The Desperate Song. This feature, supposedly

16 negative, is not intentional. What could be to describe an adolescent lover but the wonder of a wishful body or something of their parts that remembers or longs for with the most intensity? The selective memory does not respect the controls of love. It is more, to accentuate some features, deny others, and forget that which cannot or wants not to remember. More the eroticism is deceitful: you see that which you want to see and not that which another represents or wants to show. Like the same, in Twenty Poems the only wish they carry out when they think the loved in function of the intellectual joy: the memory is always more pleasant and real that the own object of desire. In effect, one time that the body of the woman is represented as a presence, the desire disappears and only makes the pleasure of remembering with pain (do you remember the verse of Jorge Manrique?).

PAGINA 14 Poem 20 and The Desperate Song illustrate better these aspects, a sentiment that the critic has christened self-compassionate: Before Residence in the Ground, in all of Nerudas poetry there is a beautiful sadness that is pleased within itself (Alonso 15). It tries added with a love like martyrdom, some other of the privileged sources of Petrarchism. The poetry, in turn, is an instrument of the memory that it serves at least of fragmentation in order to remember, forget, feel pleasure and suffer? So it would seem: the love of the Twenty Poems is like a bookish feeling (and almost mystical) and not of a concrete love. For one part, the the poet evokes and is in love with an abstraction (the modern variant of the apparition of Latin poetry) and no of a presence. The young poet, therefore, discovers his lady Marisolmbra invented from the woman. On the other hand, the remembrance and the suffering are the roads on which he intends to arrive to have a relationship with his lover,

17 but the feminine presence is always avoided, while the apparition or image arises from the poetic mind: it is close and suggests the authority of the man again the instrumentation of the feminine --. Obviously there are obstacles between the two lovers, even more they are references the distance and the forgotten of a monologue about desire where the man imprints his footprint on a distant woman and owned (mine). But love and eroticism are the two different names of sexuality. Any attractive woman can ignite eroticism. Love, on the other hand, like a culmination of sexuality and the eroticism, requires the choice of the one person, possessor of a body and a soul, characteristic that, with the exception of a magnificent stanza in Poem 14: Of no one you seem until I love you (99), you dont find in this book. The other obstacle that impedes a mutual sentiment is the fragmentation of the lady. In effect, the parts that dont tell of love: in the poetry yes because it is possible the description until a dissected position that emphasizes determined characteristics that explain the enamored to possess her.

PAGINA 15-16 Love, in consequence, is an effective form to subjugate the woman in the text of your lectures. The woman, in this conventional equation (Freud), is nothing more than an object of desire (and veneration); the bangle of poetic pleasure or the goddess whose body was confused with the universe because it is linked to itself: the lack of freedom denies communion between two beings. Here is the reason why love in this act is not a fullness but a lack, a uneasiness, a nostalgiaIt is useless to add the beloved connection it is not from affinity: the active or passive opposition isolates and denies them- communicates- affirming the masculine and subordinating the feminine. But the more worrisome, taking into account

18 the major success of reception of this text and if it prioritizes the didactic character of the literature, is that he and the lover of Twenty poems influenced the readers in a negative way: the masculinized. The reader macho can give free rein to their fantasies to dominate and possess the woman and enjoy the intellectual pleasure of the masculine conquest because it is transformed into a kind of voyeuristic accomplice of the poetic voice. In fact, the woman- the object of the text in addition to being the test of the masculine triumph, is an antidote (again an instrument) against the fear of castration, i.e. the fear of man to feminize, i.e. to approach the beloved through a mutual and shared love. The masculinization of the reader, meanwhile, is evident when it accepts the passive role that is assigned to it and behaves like and objects of contemplation and/or fetishization: the place that the patriarchal culture is assigned. My conclusion is a reiteration nothing poetic: textual dismemberment of the beloved Twenty love poems and a song of despair is a distorted representation of women because it explains separately certain parts of the body or the sum of these. Mirror and light of the eyes of the poetic voice, the person that supposedly love, or whose beauty only wants to praise, is a piece of meat- without freedom- which in many cases becomes all without what it is: a subject with an identifiable purpose.

PAGINA 17 NOTES 1. Pablo, Neruda. Twenty love poems and a desperate song, ed. Hugo Montes (Madrid: Castalia, 1989). Quoted in this edition. 2. Elizabeth Cropper's essay studying, although partially, Patrarchan influence in the painting of the rebirth. 3. In medieval times, the "portrait" was a subgenus of the beautiful poetry with the purpose of praising or criticizing: not copying. The portrait, a literary convention that inspired Petrarca

19 and the Renaissance poetry, obeyed certain rules as for the nature of stylistic expression and enumeration of the features of the lady:"C'est ainsi que, pour la physionomie on examine dans l'ordre la cheveleure, le front, les sourcils et l'intervalle qui les spare, les yeux, les joues et leur teint, le nez, la bouche et les dents, le menton; pour le corps, le cou et la nuque, les paules, les bras, les mains, la poitrine, la taille, le ventre( propos de quoi la rhtorique prte le voile de ses figures des pointes licencieuses), les jambes et les pieds" (Faral 80). 4. Debatable affirmation since the critic estimates that Petrarca forgot to describe certain feminine features: "Petrarch in fact never addressed himself to the simple enumeration of Laura's features, even though the experts of the sixteenth century succeeded in finding most of them in his poems, with the exception of her nose, which, to their great dismay, Petrarch seems to have ignored" (Cropper 386). 5. For more information about the strategy of the Petrarchan fragmentation consult the works of DalMolin, Freccero, Mirollo and Vickers. 6. Cervantes put in the mouth of Don Quixote this passage that "dissects" the lady: "[...] her hair is gold, her brow Elypsean fields, her arched eyebrows to the sky, her sunny eyes, her pink cheeks, her coral lips, pearly teeth, alabaster neck, marble bust, ivory hands, her snow whiteness [...]" (I, 13: 171-2). 7. Seeing, by example, "While of pink and white lily" by Garcilaso de la Vega, and "While competing with your hair" by Luis de Gngora. Other less known authors -- Argensola, Balbuena, Gutierre de Cetina-- also imitate the strategy of textual dismemberment of the lady. 8. Hugo Montes took notice of "plurality potential" of general critical interpretations in this text: "[...] the book has caused different readings and even contrary, that they go from an idealizer of romanticism to the crude sensorial idealism, passing through the psychological escapism and social criticism" (25). 9. The criticism has made important this association: Durn and Safir (36); Friis (12); and Mongui (15). Rodrguez Fernndez speaks, on his part, of a "god-woman"; and Camacho Guizado of the "telluric consideration of the loved" (33). 10. If it were not for the authors extra-textual declarations, it would seem that the lovers do not exist in this poem. I wrote it when the storm threatened the Souths summer. She and I were laying under a big tree, suddenly the bursts of the storm surrounded us and that is all. (Testimony chosen by Luz Machado, in Cinco conferencias de Pablo Neruda [Five conferences of Pablo Neruda], Cuadernos de Crtica Literaria [Notebooks of Literary Criticisms], Universidad Central de Venezuela [Central University of Venezuela], Caracas, 1975, p. 20). (Cited by Montes 60.) 11. Alfredo Lozanda calls this poem twilight of the isolation where the woman is absent physically and intimately (224). 12. Jorge Edwards interprets this interrogation en another manner: The poem ends with an enigmatic, repeated question and I suspect that that question is not directed this time, as in the third stanza, to the woman, but to the poet himself: Who are you, who you are? (735). 13. In this, I agree with Cheri Register that, when explaining the literary image of women, writes that it is: a symbolic fulfillment of the male writers needs (5). 14. Guillermo Araya, with apparent common sense, esteemed that Veinte poemas is a work of adolescence and that any study that doesnt take into account the adolescent character that I express here runs the risk of being inadequate or simply false (148). This observation

20 explains the incaving of the adolescent poet: being misunderstood by everyone and not wanting to understand anyone. 15. This is a variant of the image of the woman as an intermediary built by Dante. In the case of Neruda the world replaces the divinity. 16. Several studies highlight the celebration of carnal love in this collection of poems: Margarita Aguirre, Jaime Alazraki, Marlene Gottliev, Alain Sicard, y Ral Silva Castro among others. 17. The search for security through love is a accepted topic for criticism. In accordance with Carvaltho: Throughout Veinte poemas, the poet is searching for security through love; in certain moments of idealism or hope, he pretends that she does provide a refuge from his existential questioning and loneliness (152). In a more specific way, Detwiler, commenting on poem 1, writes that His lover signifies protection from solitude in the symbols arrow and rock in verse eight (87). 18. Even in the last years of life, Pablo Neruda continued to show his polygamous inclinations both in his private life and in his conceptions about women. An example of his ideas is found in the interview with Clarice Lispector en Ro de Janeiro en April of 1969. To the question, How is a woman pretty for you?, el poet responded: Made of many women. (Neruda, Obras completas V [Completed Works V]: 1101). 19. Poem 2 prolongs this identification in a more subtle manner: In the evening, the grand roots/ grow suddenly from your soul/ [] a town pale and blue/ from you newborns are fed (51). Poem 5, in contrast, is overwhelming: You fill everything, everything you fill. PAGINAS 19 Y 20 20. To see Sharmans analysis about the presentation of the woman in Veinte poemas. Pacheco Acua studies this poem from a feminine point of view. For a different interpretation of this composition see Poem XIII from Luis Rosales book. This sketch is typical of the colonial mentality. A famous pictorial example is found in Theodore de Vrys book where in an illustration one sees Amrico Vespucio taking possession of the land and of the lady America. [MEJORAR] Obviously there are exceptions; but these confirm the passivity of the woman, about which you can read in poem 3: and your silence harasses my persecuted hours (55). The character of dependence from the respectful woman to the man appears in several of the books poems: Attached to my arms like a weed [] Sweet hyacinth blue crooked for my soul (poem 6); White bee you buzz drunk from honey in my soul / and you twist in slow spirals of smoke (poem 8); your parallel body holds itself in my arms / like an fish infinitely stuck to my soul (poem 9); In order that my heart is enough for your chest, / in order that your freedom is enough for my wings (poem 12); in my sky to the twilight you are like a cloud (poem 16). Susan of Carvalho studied the symbolism of the avenues of the nerudian poem. The imposition of silence for part of the poet to his loved has been named from annihilation poetry. For another concrete example see the analysis of poem 6 from Gilda Pacheco Acua. Ronald J. Friis holds that these characteristics contribute to the attractiveness of the text: The appeal of Veinte poemas can be attributed to the elegant and direct use of language coupled with a nostalgic adolescent poets sense of alienation and separation from his beloved (11). Carlos Santander already noted this dual paradox: From there the beloved was distant even when she is present. In the cases that the apostrophe didnt manage an evocative beloved, not

21 immediately, still in those opera a process of distancing. The poet speaks to the beloved, but not in a real, objective plane, not through the poem, in the poem. In the end, the poet speaks in solitude. He recounts his being and obligation. Its a reporter of the same (102). Alain Sicard favors the thesis of the immaterial woman of this text. Keith Ellis shares this judgment: the description of the woman en each poem, until the first, is abstract and cloudy (13). The nerudian soul (Marisol or Marisombra) is, in this aspect, similar to the cervantin Dulcinea: a feminine subject invented of agreement to the interests of the author. In the few references to feminine soul, the woman is represented as being cosmic (poem 2) or seeming to the soul of me the poet (poem 15). Even this verse is debatable. One could argue that the soul is different only when its singing for the love of the possessive lover. The result of the man-woman relation, therefore, is the same: he is active and she passive. Christopher Perriam analyzes the metaphorical machismo from Nerudas poem.

22 TRADUCCION B: The discourse of desire and the fragmentation of the loved in Twenty poems of love and a song of despair

Love and passion are privileged topics in poetry. Love, especially, and its innumerable variants dominate the literature of the west. Almost all the writers of this tradition deal with the theme introducing visions that go from one extreme to the other: they idealize or they denigrate being in love. In effect, its representation ambiguous and contradictory deforms its image and, also, the relation between lovers. The woman, in this manner of thinking, more than a reflection of the flesh, is a literary mirror where the author reflects on himself in order to contemplate his doubts, aspirations, and desires. This practice, despite its aesthetic value, perpetuates the social stereotypes of the woman writer armed as masculine interests. Sigmund Freud warns: For distinguishing between male and female in mental life we make use of what is obviously an inadequate empirical and conventional equation: we call everything that is strong and active male, and everything that is weak and passive female (188). The power and danger of this conventional equation lies within the majority of people who tend to believe that it was established by nature or some other superior design to promote the patriarchal culture. In this essay I propose that the representation of love in Twenty poems of love and a song of despair by Pablo Neruda, is ambiguous and distorted because he explains love as the masculine desire to cut the body or some of parts privileged parts of the poetic voice. The male-female relation is constructed from a point of view that that favors masculine control of the feminine: he is the subject and she is the object. In this scheme the lover suffers through a

23 process of dissection that depersonalizes her in order to convert her to a male instrument that generates, apart from desire, silence, melancholy, absence, and poetry.

PAGINA 2 Neruda, nevertheless, isnt the first in textually fragmenting and objectifying the queen. The strategy is old as it confuses the reader with the beginnings of literature. It was Petrarca, nonetheless, who had the most success. And not only in fragmenting it, but in transforming his love into the ideal beautiful woman: Laura, the muse of the Canzoniere, is the canonic source of the image of the woman of the art of the Renaissance. In the poetic work of Petrarca, the female portrait is formed by a fragmented and ambiguous statement of certain psychosomatic characteristics. In fact, Laura--- the Petrarca love

object--- is a collection of eyes, hair, hands and feet. Imprecise and distorted representation since the ideal women doesnt pass as a collection of pieces without their own identity. This method of dismembering of the female body and comparing its parts to natural elements has been imitated--- and parodied--- by authors of the Spanish world, especially in the Renaissance sonnets and by the Golden Century which was abundant in this type of descriptions. In Latin America, 20 poems of love and a desperate song is a notable example of the technique of fragmenting and (dis)personifying the woman. This collection of poems, the most famous book by Pablo Neruda---the book of the masses according to Salama---, has aroused diverse and exegesis critics. My postulate is that the woman, the indispensible premise of the amorous theme, has an ineludible in 20 poems, but his revelation is ambiguous y, for that reason, contradictory. In some compositions the love is the body or some of the

24 parts (eyes, hairs, breasts, hands); in other words, on the other hand, they transform in memory, yearning, beret, door, or word. In general it is observed that of the physicalthe concrete--, the poet lists abstract characteristics that dont denote the female subject in the quality of the person. In this textual dissection makes two aspects stand out: his (dis)composition in a series

PAGINA 3 Of traits and its metaphorical allusion about nature. In the first poem, for example, the beloved is a species of Gaia that assumes the form of a: body of woman, white hills, white thighs (47) and when the poetic speaker is most clear, she is a body of skin, of moss, of eager and firm milk. / Oh the goblets of the breasts! Oh the eyes of absence! / Oh the roses of the pubis! Oh your voice, slow and sad. (47) The second poem, perhaps the most ambiguous and inscrutable of the work, introduces her to be a more abstract cosmic than that of the original textNight-Woman by Goic. But he also talks of the soul of the friendthe modern version of Petrarchs enemythat, said to be passing, is speechless, a problematic adjective because it gives the impression of her being a mannequin, emphasizing her dark dress without describing any corporal feature except a closed mouth. The third poem mentions a doll with eyes, a waist of fog and arms of transparent stone (55). Fog and stone are opposite elements, but their attributes instability and permanenceare the corporal properties of the beloved: the struggle between the concrete and the intangible, the illusion of the feminine body. The forth poem is an exception: there is no reference of a person of flesh and bone; there is, instead, one of the small mentions of the couple in fellowship: innumerable heart of

25 the wind/ beating on our loving silence. (59; my emphasis). The apparent reciprocity of the loving sentiment, without end, is diminished in order to emphasize the action of the gale: the nature is more important than the lovers. In the fifth poem, the women is reduced to hands smooth as grapes (63); in as much as in the sixth poem she is evoked in quality of grey beret, voice of bird and heart of home (67), traits that, in the context of this essay, dehumanize her in order to identify her with the domestic elements of the love: the woman as a refuge. The seventh poem alludes to the oceanic eyes of the beloved. Again: eyes, arms and breasts are described in the eighth poem where the poetic I...

PAGINA 5

Lastly, The song of desperation is more emphatic in fragment to the female record in its condition of meat beloved and forgotten: Oh meat, my meat, woman that I loved and forgot, (128). It also made a mention of arms, a bite of the mouth, kissed limbs and debatable statement-, alludes to the woman with a dirty phrase: pit of debris. The quotes are conclusive: the Twenty love poems and song of desperation butchered what it is to be in love. What is, nonetheless, the purpose of this textual dissection? Consider that there are multiple answers. I point out the obvious: the dismemberment of the woman founded a discourse of desire that transforms into an object of contemplation and fetishization, an evident aspect of the celebration of physical attributes species of close-up poetic in certain parts of the body. Whatever the function, the result is the same: the objectification of the woman in order to better use her and have her. Following this planning,

26 the female body is the site of pleasure where her masculine lover leaves his mark, and he uses it as a function of his hopes (satisfaction of needs, especially sexual and erotic throughout literary evocation). To begin, in the poem that opens the series, the I Nerudian adolescent narrates the story of his life in opposition to rest of the world. The poetic speaker is

misunderstood, which scares everyone, with the exception of his lady, refuge, and mediator between the world and the young, grim, solitary lover. The attitude of the poet is clear: use women as objects. Also, to be a sexual object for procreation: My wild peasants body undermines you/ and makes to skip the son of the earth (47), the woman is constructed as a sexual object- body, muscles, breasts, without a proper identity. Pacheco Acuas analysis of this poem summarizes these points: This drastic change of conventional imagery made some critics affirm that Neruda was not celebration love but sex. However, I think this poem is not only a celebration of the

PAGINA 6 To this objection one must add that, according to the poet, the female lover is also a weapon, a defense mechanism, that is to say, the instrument to protect itself from the world and from itself: To survive me I forged you as a weapon/ as an arrow in my arch, as a stone in my sling (47). I think these verses reveal one of the hidden topics of the poetry book: fear to the woman, feeling that will explain the young Nerudas fascination not with one but with several lovers. This polygamous fantasy is possibly forging a passive woman whose parts attract and satisfy erotic desire without feminizing the male lover since this, such as Barthes suggests, would reduce the autonomy of the male upon becoming more like a female, which, at the same time, would make love possible. Thus, by her supposedly social role to reproduce

27 the species, to generate life and to provide security, the woman associates herself with the archetypical image of Gea that resolves the analogical problemto identify the woman with natureit deepens the ignorance of herself or, at least, her partial apprehension with the consequent dissatisfaction of the male lover. In effect, the feminine body, reproducer and protector, fails in putting out the thirst, the anxieties, the fatigue and pain of the poetic self: Body of my woman, I will persist in your grace. My thirst, my unlimited anxiety, my undecided path! Dark river beds where eternal thirst continues, and fatigue continues, and infinite pain. The possessed (exploited) body of the woman cannot satisfy a single lover that requires everything in exchange for dissatisfaction, fatigue, and infinite pain. Despite the limitations perceived of this meat that delivers itself, the poetic voice continues

PAGINA 7 clinging to this; amazing persistence used in poem three where his kisses anchor and his desire nests in the female body are transformed into port and nest, places of refuge for excellence. The topic of the refugee woman is repeated in poems 6 and 12. In poem 6, as well as beret <sinecdotica> allusion by which an object replaces a body part that, in turn, explains everything , the feminine territory is the sure site (heart and home) to where the it is targeted by the deep longings of the poet: the target of the masculine arrows of poem 3. In poem 12, the chest of the lady is the space that can hold the heart of the lover: a kind of box that holds the jewel of male love. Likewise, it is said that the woman is gathering things like an old road and is populated by [] echoes and nostalgic voices (91). These

examples show that the search for protection in the geography of women is constant, as well

28 as the physical needs of the poet who cannot conceive the universe without taking possessions of his beloved or at least territorially, is to say, give it as a territory that is subject to male dominance. Object of possession and lyrical exaltation, the woman is the place the justifies the discourse of desire of the lover. We must not lose sight, however, that the female is present as an object and settled in as a subject. Poem 13 deepens body-space association referring to the feminine white atlas, an unknown land where the male marks their territory with crossfire (95). The woman, as a beauty map is the subject of possession and a source of exploration, modification, and construction. This is recognized be one of his most enthusiastic critics: Neruda doesnt only express his love for the woman he loves. He doesnt only pay admiration and burns the incense in his best words, also described the woman, he described her physical beauty, little by little, as a passionate cartographer, constructing a map of those bodies.

PAGINA 8 divine" (Meneses 101). It is about very suggestive imagery: the conquistador, this time armed with a feather, taken from a continent until then unexplored. The male presence marks, opens, penetrates and undermines a virgin land (flesh) whose passivity gives sense and validity to the action of the possessive lover. It is not strange, therefore, that the male is always in movement in the white atlas and motionless in the feminine absence. Poem 7 corroborates this interpretation. Here the lover tries to look for and/or get over falling into the clutches of the oceanic eyes of the woman (71). But the possession of the feminine space is not possible because her eyes contain the waters of mystery, the unexplored place and impossible to control; and, for that reason, the dangerous place that threatens to drown the

29 loneliness of the poet, a metaphorical reference that alludes to intimacy and the male desires. In the face of failure to own this marine territory, the conclusion of the bard is negative. Nothing good can come of the beloved woman. Distant or close, this isfollowing a feminist readingdegraded and clear in terms of absence, obscurity and horror: You only guard darkness, my distant woman in your look emerges the coast of the horror at times (71). Neither is it irrelevant to point out that the males love is intermittent in this composition, sometimes yes and sometimes no; insecurity synthesizes by the two magnificent verses: The night birds peck the first stars that twinkle like my soul when I love you (71). In poem 14 the objectivized woman reappears and available in her generative role thanks to the wish of the bard: I want to do with you what the spring does with the cherry trees (100). Here the female has a double function. First, she stresses her passive role, a land that waits for the masculine seed in order to flower and give fruit. Second, her body is a thing for exclusion: an abstract space, the theater where the representation takes place

PAGINA 9 Those verses can be interpreted as a praise of the virile power of (pro)creation because it renews the nature to propagate the species: a victory over death. The lover microcosm is also, because of the work of the beloved, the nature in this poem. But these types of verses -phallictear, penetrate, own and annul the active category of the feminine identity. The words, because of the instrumentation of the sensual body, are not a medium of communication, only a form of approximation and knowing for conquering, defeating, owning and taking refuge in the feminine emphasizing their natural function of sickening physically and spiritually (poem 2): You are mine, you are mine, woman of sweet lips,/ and my infinite dreams live in

30 your life (107) it says, to cite another example, poem 16. But perhaps poem 15 best illustrates the process of reifying the lady. In this composition the love passivity personifiedit is changing but not muting: it lives to listen to the poet. The stereotype of the woman as a reader of poetry is also noted in poem 5: In order for you to hear me my words lose themselves sometimes like the tracks of the gulls on the beaches. (63) This passage is conflictive because it sprouts a problem of communication. It implies, first of all, the intellectual complexity of the primary message of the lover and he is not understood by the lover. So it is necessary that the words transform, they adapt to the receptive level of the woman, assuming symbolic characteristics like the tracks of marine birds. The masculine knowing and feminine nature are forefront in this text. Something similar occurs in poem 15 where the man emits subtle messages and the woman

PAGINA 10 silent and appears that he didnt understand: and my voice does not touch you. This lady, additionally, not only does not speak, but her silence is the quality for excellence that satisfies the poet: I like it when you are silent because you are as absent, and you hear me from afar, and my voice does not touch you. It appears that the eyes had flown away and it appears that a kiss had closed your mouth. (103)

31 Despite the kiss that imposes silence or perhaps for this the beloved, distant and painful, it is equated to death, the soul of the poet and the melancholy word. Another time more the feminine subject did nothing more than resemble something privileged for the poetic voice, depersonification that, to some extent, summarizes the attitude of the active lover that made a woman-instrument that generates silence, melancholy, and absence. Silence that makes possible to hear the voice of the poet, absence that wakes the inspiration and melancholy that justifies the love and masculine joy, features that also observe in the famous and always anthologizes poem 20. In this text the woman-artifact produces sadness, anxiety, and poetry: I can write the more sad verses tonight (123). Another fact that instrumentalizes the beloved and relegated the traditional role of the muse inspire verses-, is the finding that its beauty is unattainable in the moment of evocation (lost love). This provocation that the poetic heart be troubled, and comfort with the recollection of having possessed in a passed time or, the paradoxical form, deny and affirm the love of the present time: Already I do not want it, it is true, but perhaps I want it(124). Its not possible to understand fully the paradoxical feeling of this verse. For my significance a negation that affirms: deny the woman affirming the love. The fragmentation of the woman in Twenty poems, and the purpose of objectifying y instrumentalizing, is observable en the majority of the compositions of the book. But, The PAGINA 12 Page 12 shipwreck. This deficit causing woman, as an individual ontological unit, is negated by the dissection process: she is flesh, affirms the poetic voice and it seems sure that she is nothing because the final products of the amorous relationship are dissatisfaction and desperation, the illusions of eroticism. On the other hand, it is interesting to note that the

32 woman in reality her arms is the poets refuge, the fruit that quenches his thirst and hunger for love; and above all else, the miracle that vanquishes the pain and ruins of a somber existence. Yet it is also another, less agreeable, situation: a cemetery of kisses the poets final refuge? and a critical mouth: lips innately consumed by violence. From this I consider that the amorous relationship is forced even when the lovers depend, up to a point, one on the other. The difference stems out from the loved person resembling an object that consumes the physical and the spiritual, but not a being of flesh and blood by its own will. In effect, the woman, exactly as she sees herself in other poems, is moved, silent, distant, or a body so inanimate that the masculine poetic ego must light up, think, and record. A lover is, in short, made of memory and oversight. But memory cant resuscitate the past. No more than it (re)creates fragmenting of the feminine, strategy that justifies the masculine necessities every time the male unit uses the female part that interests him or consumes that which attracts him. It is not difficult, in this scheme, to infer that the female body is the territory, the empty canvas where the patriarchal society writes its fantasies and obsessions; her silence, passivity, and fragmentation allow the man to be the creator of attention and significance. And, not withstanding, a great nostalgia inspires the Nerudian text: the nostalgia of the body, not fragmented but whole. Using the preceding conclusion as precedent, I believe that in Veinte poemas no convincing representation of love exists, a sentiment that combines two freewills in order to

PAGINA 13 It is a sexual exaltation and nostalgic eroticism that, through the contemplative distance, excluding the feminine, at least in its active role individually because naturally the lady is

33 very active. Following this interpretation, the beloved girl is trapped by melancholy verses that they cut her into pieces to get to know her better. The masculine poetic voice, in large measure due to the feeling of loss and alienation, denies the womans liberty, appearing as if already an illegitimate presence of love. It lacks criticizes Salama, spiritual contact. However, nostalgic eroticism is not a feature of everything negative; on the contrary, it is also to wonder, sometimes in an anguished way Who are you, who are you?- before the unknown near and far: the absent loved one yet present. The absence of the female presence makes me think that the poetic voice loves a distraction and not a person: fantasy. If you accept this, once more you conclude that love does not exist in the Twenty Poems: only eroticism and sexuality, exactly what poem 1 or The desperate song seems to fantasize about. This characteristic, supposedly negative, is not intentional. How could you describe a teenage crush without the beauty of an ideal body or one of her parts that you remember or yearning with more intensity? Selective memory does not respect the dominions of love. Whats more, in order to accentuate some of the features you deny others and forget what you cannot or do not want to remember. Also, eroticism is deceptive: it sees what it wants to see and not what the other person is or wants to show. Because of this, in Twenty Poems the wish is only complete when it thinks of the loved one according to its intellectualized enjoyment: memory is always more pleasant and real than the object of the wishing. In effect, once the body of a woman is represented as a presence, the wish disappears and only leaves the pleasure of remembering with pain.

PAGINA 14

34 Poem 20 and The Desperate Song illustrate better these aspects, a sentiment that the critic has christened self-compassionate: Before Residence in the Ground, in all of Nerudas poetry there is a beautiful sadness that is pleased within itself (Alonso 15). It tries added with a love like martyrdom, some other of the privileged sources of Petrarchism. The poetry, in turn, is an instrument of the memory that it serves at least of fragmentation in order to remember, forget, feel pleasure and suffer? So it would seem: the love of the Twenty Poems is like a bookish feeling (and almost mystical) and not of a concrete love. For one part, the the poet evokes and is in love with an abstraction (the modern variant of the apparition of Latin poetry) and no of a presence. The young poet, therefore, discovers his lady Marisolmbra invented from the woman. On the other hand, the remembrance and the suffering are the roads on which he intends to arrive to have a relationship with his lover, but the feminine presence is always avoided, while the apparition or image arises from the poetic mind: it is close and suggests the authority of the man again the instrumentation of the feminine --. Obviously there are obstacles between the two lovers, even more they are references the distance and the forgotten of a monologue about desire where the man imprints his footprint on a distant woman and owned (mine). But love and eroticism are the two different names of sexuality. Any attractive woman can ignite eroticism. Love, on the other hand, like a culmination of sexuality and the eroticism, requires the choice of the one person, possessor of a body and a soul, characteristic that, with the exception of a magnificent stanza in Poem 14: Of no one you seem until I love you (99), you dont find in this book. The other obstacle that impedes a mutual sentiment is the fragmentation of the lady. In effect, the parts that dont tell of love: in the poetry yes because it is possible the

35 description until a dissected position that emphasizes determined characteristics that explain the enamored to possess her.

PAGINAS 15 y 16 Better. The love, accordingly, is an effective way to captivate the as much in the text as in their readers. The woman, in this conventional equation, is nothing more than an object of desire (and adoration); the slave of the poetic pleasure or the goddess whose body merges with the universe because it is linked by itself: their lack of liberty denies the communion between two free beings. Here is the reason why the love in this work is not an abundance but rather a deficiency, a restlessness, a longing It works out useless to add that the beloved relationship is not of affinity: lo passive/active opposition isolates and deniescommunicates themasserting masculine things and subordinating feminine things. But more worrying, taking into account the huge success in the reception of this text and if it prioritizes the educational nature literature, is that he and the mistress of Twenty Poems affect their readers in a negative way: it masculinizes them. The male reader indulge in their fantasies of dominating and owning the woman enjoying taking intellectual pleasure in the male conquest because it is transformed into a sort of conspiratorial voyeur of the poetic voice. Indeed, the female object of the text besides being a test of the masculine triumph, is an antidote (again instrument) against the fear of castration, for example, the fear of the man to feminize, for example, to approach the mistress through mutual and shared love. The masculinization of the reader, for their part, is evident when they accept the passive role that the text assigns them and behave as an object of contemplation and fetishism: the place that patriarchal culture assigns them.

36 My conclusion is a non-poetic reiteration; the textual dismemberment of the beloved in Twenty poems of love and a desperate song is an imprecise and distorted representation of the woman because the explanation from true parts of the body or the sum of these. Mirror and light of the eyes of the poetic voice, the person who supposedly loves or whose beauty only wants praise, is a piece of meatand without libertythat in many cases returns everything without being what it is: a character with their own identity. Speech about desire and fragmentation of the lovers in Twenty Love Poems and a Desperate Song Love and passion are common topics in poetry. innumerable variants are found in western literature. Most notably love and its

Almost all the writers from this

background deal with the theme by introducing views that vary from one extreme to the other: they idealize or denigrate being in love. In effect, their representation ambiguous and contradictory deforms its image and, also, the relations between lovers. The woman, in this model, more than a reflection of a being made of flesh and bone, is a literary mirror where the authors reflect themselves to contemplate their doubts, aspirations, and desires. This practice, besides its aesthetic value, perpetuates stereotypes associated with women being discrete and armed, following the interests of their masculine counterpart. Sigmund Freud warns that, For distinguishing between male and female in mental life we make use of what is obviously an inadequate empirical and conventional equation: we call everything that is strong and active male, and everything that is weak and passive female (188). The power and danger in this conventional wisdom lies in that a majority of people are resigned to believe that it was established by nature or by some other superior design with conventions to promote a patriarchal culture.

37 This essay proposes that the representation of love in Twenty Love Poems and a Desperate Song by Pablo Neruda, is ambiguous and distorted because it explains love by means of the body or some of the parts favor masculine desire in the poetic voice. The manwoman relationship is constructed from a point of view that favors masculine dominance over that of the female: He is the subject and she is the object. In this model, love suffers a dissection process that de-personifies it in order to convert it into a woman-instrument that also generates, desire, silence, sadness, absence, and poetry. Pablo

NOTES:

10. If not for extra textual declarations of the author it would seem that the lovers dont exist in this poem: I wrote it when a storm of the summer of the South was threatening. She and I were stretched out under a great tree, suddenly a gust of the gale wrapped us and that is all. (Testimony taken by Luz Machado, in Cinco conferencias de Pablo Neruda, Cuadernos de Crtica Literaria, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, 1975, p. 20). (Quoted in Montes 60). 11. Alfredo Lozada called this poem: twilight of isolation where physically and intimately the woman is absent (244). 12. Jorge Edwards interprets this question in another way: The poem ends in an enigmatic question, repeated, and I suspect that that question is not directed this time, as in the third stanza, at the woman, but to the poet himself: Who are you, who are you? (735). 13. In this I agree with Cheri Register whom, to explain the feminine literary image, writes that its: a symbolic fulfillment of the male writers needs (5). 14. Guillermo Araya, with apparent common sense, thinks that Veinte poemas is an adolescent work and that any study that doesnt have an account of the adolescent character that is expressed here runs the risk of being inadequate or simply false (148). This observation explains the encuevamiento of the adolescent poet: to be misunderstood by all and not wanting to understand anyone. 15. This is a variation on the image of the woman as an intermediary built by Dante. In the case of Neruda the world replaces the divinity.

38 16. Various studies emphasize the celebration of the carnal love in this book of poems: Margarita Aguirre, Jaime Alazraki, Marlene Gottlieb, Alain Sicard, y Ral Silva Castro, among others. 17. The search for security through love is an accepted topic for the critic. Carvalho agrees: Throughout Veinte poemas, the poet is searching for security through love, in certain moments of idealism or hope, he pretends that she does provide a refuge from his existential questioning and loneliness (152). In a more specific manner, Detwiler, commenting on the first poem, writes that: His lover signifies protection from solitude in the symbols flecha (arrow) and piedra (stone) in verse eight (87). 18. Even in his last years of life, Pablo Neruda continued expressing his polygamist inclinations as much in his private life as in his conceptions about the woman. An example of his ideas can be found in the interview that he granted to Clarice Lispector in Ro de Janeiro in April of 1969. To the question How is a woman beautiful to you? the poet responded: [My life is] made of many women (Neruda, Obras completes V: 1101). 19. Poem 2 prolongs this identification more subtly: Of the night the big roots/ they grew suddenly from your soul/ [] a pale and blue town/ recently born of you feeds (51). Poem 5, instead, is blunt: You fill it all, fill it all (63).

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Cult of The Literary Sad Woman: EssayDocument12 paginiCult of The Literary Sad Woman: EssaySelahattin ÖzpalabıyıklarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Katherine Mansfield's Modernist Short StoriesDe la EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Katherine Mansfield's Modernist Short StoriesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poe's Gothic Protagonists: Isolation and MelancholyDocument24 paginiPoe's Gothic Protagonists: Isolation and MelancholyAnonymous Z1webdoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ready Reference Treatise: The French Lieutenant's WomanDe la EverandReady Reference Treatise: The French Lieutenant's WomanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Newland Archer's State of Mind in The Age of Innocence (1920)Document6 paginiAnalysis of Newland Archer's State of Mind in The Age of Innocence (1920)MahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Street Car Allusions and ReferDocument2 paginiA Street Car Allusions and ReferMarcusFelsmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fight Club Through A Feminist LensDocument3 paginiFight Club Through A Feminist LensFigenKınalıÎncă nu există evaluări

- Two BodiesDocument8 paginiTwo Bodieskathy lowe50% (2)

- A Portrait Epiphanies PDFDocument25 paginiA Portrait Epiphanies PDFMarielaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dissertation Viva 31 1Document279 paginiDissertation Viva 31 1Saba Ali100% (1)

- Bob KaufmanDocument8 paginiBob KaufmanEric MustinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syllabus Contemporary LiteratureDocument2 paginiSyllabus Contemporary LiteratureEdwin PecayoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Griffith - Chapter 5 - Interpreting Poetry PDFDocument16 paginiGriffith - Chapter 5 - Interpreting Poetry PDFAnggia PutriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chekhov SocietyDocument53 paginiChekhov SocietyRose BeckÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Agendas in Mary Barton and Hard Times: Authorial Intention & Narrative Conflict (Victorian Literature Essay)Document16 paginiSocial Agendas in Mary Barton and Hard Times: Authorial Intention & Narrative Conflict (Victorian Literature Essay)David JonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leslie Marmon Silko's Ceremony Ceremonial SceneDocument3 paginiLeslie Marmon Silko's Ceremony Ceremonial SceneDevidas KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21 Love PoemsDocument2 pagini21 Love PoemsNidal ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

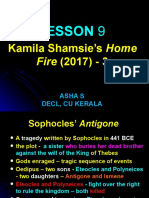

- Lesson 9: Kamila Shamsie's HomeDocument24 paginiLesson 9: Kamila Shamsie's HomeAsha SÎncă nu există evaluări

- PPT For Creating Texts.Document17 paginiPPT For Creating Texts.Epic Gaming Moments100% (1)

- Critical Models of Post-Colonial LiteratureDocument21 paginiCritical Models of Post-Colonial Literaturecamila albornoz100% (1)

- Leaving The MotelDocument5 paginiLeaving The Motelapi-303073835Încă nu există evaluări

- SP and Anie Sexton - TThesisDocument330 paginiSP and Anie Sexton - TThesisgcavalcante4244Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Ass On Absurd DramaDocument5 paginiFinal Ass On Absurd DramaSabbir N BushraÎncă nu există evaluări

- BeautifulyoungnymphDocument14 paginiBeautifulyoungnymphapi-242944654Încă nu există evaluări

- SlouchingreadingscheduleDocument2 paginiSlouchingreadingscheduleapi-288676741Încă nu există evaluări

- Pedro Paramo Ghost QuoteDocument1 paginăPedro Paramo Ghost QuotelzeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Poems of IdentityDocument4 paginiThe Poems of Identityapi-348900273Încă nu există evaluări

- Byronic HeroDocument2 paginiByronic HeroMonica AnghelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Little Prince Loneliness An Essay On LonelinessDocument1 paginăLittle Prince Loneliness An Essay On LonelinessLuis Felipe HallerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 An Interview With Manuel PuigDocument8 pagini4 An Interview With Manuel Puigapi-26422813Încă nu există evaluări

- Epiphany in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young ManDocument4 paginiEpiphany in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young ManATIQ UR REHMANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poetics Today 2002 Richardson 1 8Document8 paginiPoetics Today 2002 Richardson 1 8gomezin88Încă nu există evaluări

- John Donne's Religious Poetry and Metaphysical StyleDocument5 paginiJohn Donne's Religious Poetry and Metaphysical StyleOmar Khalid ShohagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Promt For The Bluest Eye Analytical ProjectDocument4 paginiPromt For The Bluest Eye Analytical Projectapi-262637181Încă nu există evaluări

- Love Ethics of D.H. LawrenceDocument1 paginăLove Ethics of D.H. LawrenceDaffodilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emily Dickinson's poem "I like to see it lap the MilesDocument3 paginiEmily Dickinson's poem "I like to see it lap the MilesKinza SheikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aristotle Poetics Paper PostedDocument9 paginiAristotle Poetics Paper PostedCurtis Perry OttoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anne Hathaway (Annotated)Document1 paginăAnne Hathaway (Annotated)Tiegan BlakeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Araby A Structural Analysis PDFDocument3 paginiAraby A Structural Analysis PDFErvin RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Victims by Sharon OldsDocument4 paginiThe Victims by Sharon OldsTmatem TmatemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soapstone Analysis ChartDocument2 paginiSoapstone Analysis ChartAbhac KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uncanny Singing from Certain HusksDocument6 paginiUncanny Singing from Certain HusksMorgana PendragonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adrienne Rich - The Poet and Her Critics. by Craig WernerDocument3 paginiAdrienne Rich - The Poet and Her Critics. by Craig WernerFernanda OrdazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sylvia Plath A Great DepressionDocument8 paginiSylvia Plath A Great DepressionRuben TabalinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poem - The Runaway Slave at Pilgrims Point - Elza Browning - Tariq Makki OrginialDocument4 paginiPoem - The Runaway Slave at Pilgrims Point - Elza Browning - Tariq Makki Orginialapi-313775083Încă nu există evaluări

- Character in If On A Winter's Night A TravelerDocument6 paginiCharacter in If On A Winter's Night A Travelerdanilo lopez-roman0% (1)

- Postcolonial Analysis Love MedicineDocument8 paginiPostcolonial Analysis Love Medicineapi-583025922Încă nu există evaluări

- Notes On Barthes SZDocument8 paginiNotes On Barthes SZRykalskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nothing Gold Can StayDocument7 paginiNothing Gold Can StayMaizaton Akhmam MahamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Apple GatheringDocument4 paginiAn Apple GatheringSubhajit DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Fiction 1970s-1980sDocument50 paginiAmerican Fiction 1970s-1980sVirginia IchimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marsden, Jill - Review of Inner TouchDocument11 paginiMarsden, Jill - Review of Inner TouchCostin ElaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Questions of Travel by Elizabeth BishopDocument11 paginiQuestions of Travel by Elizabeth Bishopsebastian verÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catcher in The Rye - Study PackDocument8 paginiCatcher in The Rye - Study PackhaydnlucawhyteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eng Ext1 - Pans Labyrinth Quotes and AnalysisDocument22 paginiEng Ext1 - Pans Labyrinth Quotes and Analysiskat100% (1)

- John Donne's Poetry in The Context of Its Time: Tutorial Project Semester: 2Document4 paginiJohn Donne's Poetry in The Context of Its Time: Tutorial Project Semester: 2Aadhya GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nick and The Candlestick Analysis FINALDocument5 paginiNick and The Candlestick Analysis FINALchixon1100% (1)

- Exact Differential EquationsDocument7 paginiExact Differential EquationsnimbuumasalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pas 62405Document156 paginiPas 62405Nalex GeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignmen1 PDFDocument5 paginiAssignmen1 PDFMaryam IftikharÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eyes Are Not Here Q & ADocument2 paginiEyes Are Not Here Q & AVipin Chaudhary75% (8)

- The Return of The DB2 Top Ten ListsDocument30 paginiThe Return of The DB2 Top Ten ListsVenkatareddy Bandi BÎncă nu există evaluări

- Canteen Project ReportDocument119 paginiCanteen Project ReportAbody 7337Încă nu există evaluări

- Zero Conditional New VersionDocument12 paginiZero Conditional New VersionMehran RazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Word Meaning Practice Test 1Document9 paginiWord Meaning Practice Test 1puneetswarnkarÎncă nu există evaluări