Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Market Perspectives Feb 2013

Încărcat de

Arslan Zafar0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

49 vizualizări0 paginiInvestors routinely make a series of fundamental missteps. Extreme fear of losses may deter an investor from investing in risky assets. Behavioral finance research can help investors avoid some common pitfalls.

Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentInvestors routinely make a series of fundamental missteps. Extreme fear of losses may deter an investor from investing in risky assets. Behavioral finance research can help investors avoid some common pitfalls.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

49 vizualizări0 paginiMarket Perspectives Feb 2013

Încărcat de

Arslan ZafarInvestors routinely make a series of fundamental missteps. Extreme fear of losses may deter an investor from investing in risky assets. Behavioral finance research can help investors avoid some common pitfalls.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 0

Breaking Bad Behaviors

Understanding Investing Biases and How to Overcome Them

iShares Market Perspectives | February 2013

i S H A R E S MA R K E T P E R S P E C T I V E S [ 2 ]

Nelli Oster, PhD

Investment Strategist,

BlackRock Multi-Asset

Strategies Group

Russ Koesterich,

Managing Director,

iShares Chief

Investment Strategist

Finance experts have long assumed that investors are

rational, able to process information efciently, evaluate

investment options in an unbiased fashion, and seek to

maximize prots while minimizing risks. The reality is often

more complex, however. In fact, investors routinely make a

series of fundamental missteps. Common ones include:

holding too much cash for too long;

not being sufciently diversied;

trading too frequently;

buying familiar or attention-grabbing assets; and

being reluctant to realize losses even if tax advantageous.

What are the consequences of these mistakes? To cite just one example, an extreme fear

of losses and an undue focus on the short-term performance of an individual asset may

deter an investor from investing in risky assets at all. The costs can be substantial:

adjusted for ination, the return on cash left in a bank account was negative for 2012. In

comparison, world equity markets as measured by the MSCI All Country World Index

returned 13.4% in US dollar terms during the same period. The performance difference

is even greater over time: while an investor would have by the end of 2012 almost

doubled his initial investment made in the world stock markets during the lows of March

2009, a $100 investment made 10 years earlier would have also grown to $178, and 25

years earlier to $340. And this is in addition to any dividends that an investor would have

received during his investment period.

1

Recent years have seen a proliferation in behavioral nance research, which incorpo-

rates insights from psychology about how people actually make decisions and ways in

which they tend to deviate from full rationality. We think that an understanding of these

biases can help investors avoid some common pitfalls and position their portfolios to

better suit their investment needs, enhancing long-term investment performance. This

paper takes a look at whats behind the common mistakes investors make, what those

mistakes are, and potential solutions to mitigate the impact of these biases on portfolio

performance. Those solutions include:

broadening the concept of invested wealth beyond stock market investments;

lengthening the investment horizon to increase comfort around investing in risky assets;

increasing portfolio diversifcation by investing in well-diversifed index funds, ETFs or

lifestyle or target date funds; and

rebalancing periodically with a rules-based or systematic investment approach to

help mitigate investor inertia and biases.

Executive Summary

1

The strategies discussed are strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and should not be construed as a

recommendation to purchase or sell, or an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. There is no guarantee

that any strategies discussed will be effective. The information provided is not intended to be a complete analysis of every

material fact respecting any strategy. The examples presented do not take into consideration commissions, tax implications

or other transactions costs, which may signicantly affect the economic consequences of a given strategy.

i S H A R E S MA R K E T P E R S P E C T I V E S [ 3 ]

Why We Do the Things We Do: Common Biases

Logic: The art of thinking and reasoning in strict accordance with

the limitations and incapacities of the human misunderstanding.

Ambrose Bierce

While most economic and nance literature assumes that

investors behave rationally and seek to maximize prots and

minimize risks, evidence from psychology suggests otherwise. In

real life, the way people come up with their beliefs and how they

behave is often a lot messier, confounded by mental limitations to

processing all available information, limited willpower, and

emotional and social considerations.

For example, presented with a wealth of options to choose from

and an abundance of information about these options, people

may feel overwhelmed and ultimately not act, refusing to choose

at all. The eld of behavioral nance focuses on understanding

the impact of actual observed human beliefs and preferences on

investment decisions. What follows are some of the cognitive

errors and preferences that have been shown to deter individuals

from making sound investment decisions.

Keeping it simpletoo simple. To deal with the complex world

around us, people often rely on simplifying rules of thumb,

sometimes referred to as heuristics, in forming their beliefs and

making decisions. For example, when assessing the likelihood of

an event occurring, people naturally tend to focus on factors such

as how frequently they have observed it already, or how easy it is

for them to recall it. For example, people tend to put too much

weight on or overreact to information that is recent or otherwise

easily recalled, salient and colorful, while ignoring equally

important evidence that happens to be mundane, boring or

foreign in nature. Advertisers have long used frequent repetition

to make an audience more likely to believe their statements.

Similarly, people often think that small samples should resemble

in their essential characteristics the larger population from which

they are drawn, an effect known as representativeness.

When it comes to investing, this tendency to rely on the simpler

rule of thumb in understanding complex concepts can lead

individuals astray. For example, to simplify matters, or perhaps to

impose self-control over spending, some households divide their

savings into separate accounts for retirement, college, vacation

and other needs. This is known as mental accounting. While this

may seem benign, it can reduce the benets from pooling

investments and diversifying their risks. Nave or insufcient

diversication may also arise from the allocation of savings

equally across chosen assets, known as the 1/n rule. When

applied to retirement plan funds, for example, this rule has the

undesirable characteristic of making the outcome dependent on

plan design details that should be irrelevant for evaluating future

investment performance, such as the number of funds available,

or the number of bond versus stock funds offered. Retirement

plan design may be especially important for less sophisticated

investors, who may perceive the offering of a fund as an implicit

recommendation by the plans sponsor.

2

Seeing the glass half full. People tend to be optimistic and think

that they are correct more often than is the case. And they often

overestimate their own ability to do well in assigned tasks,

especially when important to them personally. For example, in

one study, 93% of American and 69% of Swedish students

thought that they were more skillful than the median driver.

5

And

in another study, 81% of entrepreneurs thought that they had a

good chance of success, yet less than 40% thought that any

business like theirs did.

6

2

Benartzi, S. and Thaler, R. H. (2001) Naive Diversication Strategies in Dened

Contribution Saving Plans, American Economic Review, Vol. 91, Issue 1, 79-98.

3

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1983) Extensional versus Intuitive Reasoning: The

Conjunction Fallacy in Probability Judgment, Psychological Review, 90, 293-315.

4

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1972) Subjective Probability: A Judgment of

Representativeness, Cognitive Psychology, 3, 430-454.

5

Svenson, O. (February 1981) Are we all less risky and more skillful than our

fellow drivers? Acta Psychologica, 47 (2), 143-148.

6

Cooper, A.C., Woo, C.Y. and Dunkelberg, W.C. (1988) Entrepreneurs perceived

chances for success, Journal of Business Venturing, 3(2), 97-108.

TEST YOUR BIAS

Example 1:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken and very bright. She

majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned

with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also

participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Choose the option that is more likely:

(a) Linda is a bank teller.

(b) Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Tversky and Kahneman

3

found that 85% of respondents chose

(b) over (a), presumably paying more attention to Lindas

characteristics that were easily available for mental processing

and representative of a feministhowever, since feminist bank

tellers are a subset of bank tellers, the latter are at least as likely

as the former.

Example 2:

Please rank the following in their order of likelihood, where H

depicts heads and T tails in a coin toss:

(a) H-T-H-T-T-H

(b) H-H-H-T-T-T

(c) H-H-H-H-T-H

According to Kahneman and Tversky

4

people tend to think that (a)

is more likely than (b) or (c) as the latter do not appear random; in

reality all three sequences are equally likely for an unbiased coin.

This is an example of representativeness, the expectation that

even small samples should represent the essential characteristics

of the process that was used to generate them, and may lead

people to believe that (b) and (c) were produced by biased coins.

i S H A R E S MA R K E T P E R S P E C T I V E S [ 4 ]

Moreover, the more condent a person is in his own knowledge

or abilities, the more likely he is to downplay information that

contradicts his own. In the investment world, investors may also

attribute positive performance to their own skill but losses to

bad luck, leading to overcondence (until he or she eventually

becomes discouraged).

7

Not seeing the big picture. Another way in which people differ

from the fully rational and self-interested homo economicus is

by not taking into account their entire wealth with asset-specic

risks diversied away. Instead, people tend to focus on specic

investments in isolation. This is an example of what in the eld

of psychology is known as narrow framing of the context in which

a decision is made or presented.

Myopic view on gains and losses. Individuals are usually much

more sensitive to losses than gains in their portfolios. In fact,

studies have estimated the pain from losses to be roughly twice

as impactful as the joy from gains. As a result, people are usually

risk averse for gains, preferring a sure gain to a gamble with the

same expected value, while happy to take on gambles that may

allow them to avoid a loss. In addition, gains and losses are often

evaluated over a relatively short time horizon that may not be in

sync with the longer horizon over which investment goals are

expected to be achieved. Together, the disproportionate dislike

of losses and mental focus on an inappropriately short horizon

are known as myopic loss aversion

Aversion to ambiguity. People prefer known and quantiable

risks to unknown and ambiguous risks, and usually pick choices

with the fewest unknown factors. Insurance companies are well

aware of loss and ambiguity aversion and frame their marketing

pitches accordingly, making a potential customer imagine large

losses that are caused by someone or something else. A similar

phenomenon commonly occurs when it comes to investing.

Fear of regret. Finally, there is the fear of regret from making poor

choices. In addition to losses, regret may also arise from realizing

gains too early, not choosing another investment instead, or some

other alternative that was initially considered but not selected.

Exposure to potential regret may lead an individual to prefer the

status quo and refuse to take any action at all, e.g., staying out of

the stock market altogether.

The good news is that there is some hope for investors as

learning through experience has been found to mitigate some of

these biases. Cognitive mistakes like those described above tend

to be more common when reliable information is scarceand

uncertainty high.

TEST YOUR BIAS

Example 3:

1) In addition to whatever you own, you have been given $1,000.

Which of the following would you prefer?

(a) 50% chance of getting $1,000

(b) Getting $500 for sure

2) In addition to whatever you own, you have been given $2,000.

Which of the following would you prefer?

(c) 50% chance of losing $1,000

(d) Losing $500 for sure

Kahneman and Tversky

8

found that the majority of their subjects

chose (b) and (c), reecting risk aversion for gains and risk-seeking

behavior for losses. However, (a) and (c) boil down to the same

thing, as do (b) and (d). Since the bonuses of $1,000 and $2,000

were common for the two options in the two questions, people

essentially ignored them in their decision making. Instead of total

wealth, the usual assumption in nance theory, people focused on

changes in their wealth.

TEST YOUR BIAS

Example 4:

There is an urn with 30 red balls and 60 balls that are either black

or yellow, with the exact numbers unknown. One ball will be drawn

from the urn at random.

1) Which of the following would you prefer?

(a) $100 if a red ball is drawn

(b) $100 if a black ball is drawn

2) Which of the following would you prefer?

(c) $100 if a red or a yellow ball is drawn

(d) $100 if a black or a yellow ball is drawn

Slovik and Tversky

9

found that most people prefer (a) to (b) and (d)

to (c). This violates rational decision making under uncertainty.

Choosing (a) over (b) implies that the decision maker believes that

the likelihood of a black ball is less than one third, the probability

of a red ball. Choosing (d) over (c) implies that the decision maker

believes that the probability of a red or a yellow ball is less than two

thirds, the probability of drawing a black or a yellow ball. However,

if the probability of drawing a black ball is less than one third, it

must be the case that the probability of drawing a yellow ball is

more than one third, and the probability of drawing a red or a yellow

ball therefore more than two thirds. Therefore choosing (a) over

(b) and (d) over (c) are incompatible with rationality. This is known

as the Ellsberg paradox, and highlights peoples tendency to avoid

ambiguity, preferring options with the fewest unknown elements.

7

Gervais, S. and Odean, T. (2001) Learning to Be Overcondent, Review of Financial

Studies (Spring 2001) Vol. 14, No.1, pp.1-27.

8

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979) Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under

Risk, Econometrica, XLVII (1979), 263-291.

9

Slovic, P. and Tversky, A. (1974) Who accepts Savages axiom? Behavioral Science,

19, 368373.

i S H A R E S MA R K E T P E R S P E C T I V E S [ 5 ]

The Impact of Investor Biases

The investors chief problemand even his worst enemy

is likely to be himself.

Benjamin Graham

The biases described above have a signicant impact on

investors portfolios, particularly with respect to stock market

participation, baseline portfolio allocations and trading behav-

ior. Lets take a look at each of these.

To invest or not to invest: An extreme fear of losses in the near

term may deter an individual from investing in risky assets such

as equities altogether. Yet, while stock prices may be highly

volatile, particularly over the short term, they may still be worth

including in a portfolio, especially if they are not perfectly

correlated with other assets, such as housing, labor income,

and so forth, providing diversication benets. For example,

while the stock market may be down one year, the losses may

be offset by an increase in the investors house price, and vice

versa. As we noted above, it is important to view all of ones

assets as the total portfolio, and when considering investing in

the stock market, evaluate its incremental risk to existing wealth

risks, rather than focusing on each asset in isolation.

Yet many individual investors succumb to narrow framing,

looking at each of their investments in isolation,

which, together

with myopic loss aversion, the extreme avoidance of short-term

losses, helps explain individuals reluctance to invest in risky

assets and the low stock market participation rates.

10

In

addition, myopic loss aversion has shed extra light on the equity

premium puzzle,

11

the nding that the historically high differ-

ence between equity and government bond returns requires

investors to have an anomalously high degree of risk aversion.

So how common is stock market avoidance, and what does it

cost an investor to stay in cash? Based on a detailed and

comprehensive study from Sweden, 62% of all Swedish house-

holds were invested in risky assets in 2002. The estimated return

loss for the 38% of households that did not invest in risky assets

was 4.3% a year. However, most of the non-participating

households were demographically similar to households that

tend to invest cautiously and inefciently. Once accounting for

the fact that most of these households would therefore probably

not have held fully diversied portfolios, the estimated return

loss drops to around 2% a year.

12

The costs of staying out of risky assets can be substantial,

particularly in the current, low-yield environment: adjusted for

ination, the return on cash left in a bank account was negative

for 2012. In comparison, world equity markets as measured by

the MSCI All Country World Index returned 13.4% in US dollar

terms during the same period. The performance difference is

even greater over time: while an investor would have by the end

of 2012 almost doubled his initial investment made in the world

stock markets during the lows of March 2009, a $100 investment

made 10 years earlier would have also grown to $178, and 25

years earlier to $340 by now. And this is in addition to any

dividends that an investors would have received during his

investment period.

Both stock market participation and investment allocation

choices are inuenced by past personal experiences. Swedish

investors increased their portfolio diversifcation after Erics-

sons losses at the bursting of the technology bubble highlighted

the perils of concentrated portfolios. In another study based on

more than 40 years of data, people in the United States who had

experienced high stock market returns throughout their lives

were more willing to take on risk and invest in stocks, whereas

those who had lived through periods of high ination tended to

dislike bonds (without ination protection). Further, the younger

and less experienced an individual, the more impact each years

experience had on his expectations.

13 14

What this may imply is

that people who got burned perhaps not only once but twice in

the past decades stock markets may be more reluctant to put

money to use, especially if they had not beneted from the long

bull market before that.

What may in todays uncertain and volatile macroeconomic

environment compound the impact of myopic loss aversion and

adverse personal experiences on stock market (non-)participation

is aversion to ambiguity. With the worlds stock markets increas-

ingly driven by politics and policy makers actions and expecta-

tions thereof, investing has become much more of an art than hard

science. In addition, recent natural disasters such as the earth-

quake in Japan or Hurricane Sandy are still salient in many

peoples memories, and those risks are extremely hard to quantify.

Other factors that may deter individuals from investing in the

stock market include inertia and confusion around too many

choices. For example, despite the attractiveness of dened

contribution plans for saving, with contributions tax deductible,

accumulations growing tax deferred and many companies

matching their employees contributions, retirement plan

10

Barberis, N., Huang, M. and Thaler, R. (2006) Individual Preferences, Monetary

Gambles, and Stock Market Participation: A Case for Narrow Framing, American

Economic Review, 96, 1069-1090.

11

Benartzi, S. and Thaler, R. H. (1995) Myopic Loss Aversion and the Equity Premium

Puzzle, Quarterly Journal of Economics, CX, 73-92.

12

Calvet, L. E., Campbell, J. Y. and Sodini, P. (2007) Down or out: Assessing the welfare

costs of household investment mistakes, Journal of Political Economy, 115, 707-747.

13

Nagel, S. and Malmendier, U. (February 2011) Depression Babies: Do Macroeconomic

Experiences Affect Risk-Taking? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(1), 373-416.

14

Nagel, S. and Malmendier, U. (2012) Learning from Ination Experiences, Working Paper.

i S H A R E S MA R K E T P E R S P E C T I V E S [ 6 ]

enrollment rates in both the United States and the United

Kingdom have been surprisingly low. When automatic enrollment

simplied the enrollment process, participation rates increased

substantially. In the same vein, with contribution rates typically

quite low, anchored on the default options or determined by

some other rule of thumb such as maximizing company matching

contributions, the savings observed in 401(k) accounts have

usually been insufcient to cover retirement needs.

15

While typically the more choices an individual is offered the

better off he should be, in reality too many choices can become

paralyzing. Consumers can become overwhelmed and delay

their decisionor ultimately not choose at all. For example, one

study highlighted that people were found to be more likely to buy

gourmet jams when offered a more limited assortment, and

turned out to be more satised ex post.

16

Similarly, participation

rates have been found to be lower in 401(k) plans that offer 10 or

more fund options.

17

A word for any retirement plan sponsors:

the wider the range of potential investments, the more people

may feel that they are exposing themselves to regret from

unsuccessful choices, and the more likely they may be to freeze

in their tracks and not invest at all.

Portfolio choice: When individual investors do take the plunge,

they often apply nave rules of thumb that result in holding

familiar assets in concentrated portfolios. An example is the

so-called 1/n rule, where an investor divides his retirement

assets evenly among the funds his or her employer offers as

401(k) plan options. While the 1/n rule may yield a relatively

well-diversied portfolio, it may not correspond well to an

investors personal risk tolerance. For example, while a concen-

tration in stock funds may be reasonable for someone young, for

a worker close to retirement age this would often be deemed too

risky of an allocation.

18

Perhaps thanks to a bloated belief in ones investing abilities,

many individual investors are underdiversied. In a 1991 to 1996

study of the customers of a large US discount brokerage, more

than 25% held only one stock, and more than 50% held three or

fewer stocks. However, a well-diversied portfolio should

include at least 10 to 15 stocks, which only 5% to 10% of the

investors held in any given period. And generally speaking, the

more diversied portfolios performed better: the most diversi-

ed investor group earned more than 2% a year higher returns

than the least diversied group. Demographically, the young,

those with lower incomes, and workers in non-professional

categories tended to hold the least diversied portfolios.

19

Furthermore, in evaluating potential investments, individuals

tend to go with familiar names that they can recall easily,

focusing on their home markets. In an early study on the topic,

domestic equity as a percentage of overall equity was found to

be 94% for US, 98% for Japanese and 82% for British

investors.

20

This is known as the home country bias, and even

presumably more sophisticated investors can suffer from it.

A 2011 study of endowments by the National Association of

College and University Business Ofcers showed that colleges

and universities (especially those with smaller endowments)

still tend to have a persistent overweight in US equities,

although this overweight has gone down over time.

Underdiversication may also arise from a concentrated

position in the stock of an employees rm. It has been estimat-

ed that 11 million Americans have invested more than 20% of

their retirement savings in their company stock, and ve million

more than 60%.

21

While there may be additional sweeteners for

owning ones company stock, this effectively amounts to

anti-hedging of what is for most their main source of income,

employment. The relative value of holding a single stock as

opposed to a diversied portfolio has been shown to be inversely

related to the fraction of wealth in the stock, the investment

horizon and the stocks volatility. For example, allocating 50% of

total wealth to a well-diversied pension plan, and 50% of the

pension plan investments, i.e., 25% of total wealth, to company

stock has been estimated to decrease the risk-adjusted value of

the portfolio by more than one half over a horizon of 15 years.

22

15

Benartzi, S. and Thaler, R. H. (Summer 2007) Heuristics and Biases in Retirement

Savings Behavior, Journal of Economic Perspectives.

16

Iyengar, S. S. and Lepper, M. R. (December 2000) When choice is demotivating: Can

one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

Vol. 79(6), 995-1006.

17

Sethi-Iyengar, S., Huberman, G., and Jiang, W. (2004) How Much Choice is Too Much?

Contributions to 401(k) Retirement Plans, In Mitchell, O.S. and Utkus, S. (Eds.) Pension

Design and Structure: New Lessons from Behavioral Finance, 83-95, Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

18

Benartzi, S. and Thaler, R. H. (2001) Naive Diversication Strategies in Dened

Contribution Saving Plans, American Economic Review, Vol. 91, Issue 1, 79-98.

19

Goetzmann, W. N. and Kumar, A. (2008) Equity Portfolio Diversication, Review of

Finance, Vol. 12, No. 3, 433-463.

20

French, K. and Poterba, J. (1991) Investor Diversication and International Equity

Markets, American Economic Review, 81 (2), 222-226.

21

Mitchell, S. O. and Utkus, S. P. (2004) The Role of Company Stock in Dened

Contribution Plans, In Olivia Mitchell and Kent Smetters (Eds.) The Pension Challenge:

Risk Transfers and Retirement Income Security, 33-70,Oxford: Oxford University Press.

22

Meulbroek, L. (March 2002) Company Stock in Pension Plans: How Costly Is It?

Working Paper No. 02-058, Harvard Business School, Cambridge, MA.

Perhaps thanks to a bloated

belief in ones investing abilities,

many individual investors are

underdiversied.

i S H A R E S MA R K E T P E R S P E C T I V E S [ 7 ]

Trading: Generally speaking, individual investors tend to

move in and out of positions in an inefcient way, reducing

their potential prots.

First, individual investors are often overly condent in their

own abilities to beat the market, trading excessively and hurting

portfolio performance. In one study, customers of a large

discount brokerage house who traded the most earned an

average annual net portfolio return of 11.4% between 1991

and 1996, versus the market return of 17.9%.

23

In another study,

investors who switched from phone to online trading in the

1990s tended to trade more actively than before, and while they

initially beat the market by 2%, after the switch they ended up

lagging the market by 3% a year.

24

Interestingly, men have been

found to be particularly condent in their own skills and trade on

average almost 50% more than women, underperforming

women by 0.94% a year.

25

Individual investors often extrapolate past returns, buying

assets whose prices have gone up. Just as investors gravitate

toward companies that have featured prominently in the news,

good performance tends to grab attention.

26

Investors may also

expect high stock returns to be followed by high returns and low

by low. In one study, employees of rms whose stocks had done

the best in the previous 10 years invested almost 40% of their

discretionary contributions to 401(k) plans in their company

stock, versus about 10% for the worst performing companies.

Yet the extreme allocations did not predict future stock re-

turns.

27

More generally, if not justied by fundamentals, price

increases actually indicate that assets have become more

expensive, foreboding potential reversal and lower expected

returns in the future.

When selling stocks, individual investors tend to be more likely

to get rid of stocks that have done well in the past and keep

losers, avoiding the mental pain associated with realizing losses

and being able to continue their denial. This is known as the

disposition effect, and is particularly striking as tax consider-

ations would lead to the exact opposite conclusion, selling losers

to exploit capital losses and deferring taxable gains. Moreover,

according to a study on the customers of a large national

discount brokerage, the winners that were sold actually contin-

ued outperforming the losers that were held. By selling the loser

rather than the winner an individual could have increased his net

returns by an estimated 4.4% the following year net of taxes.

28

Potential Solutions

Those who are unwilling to invest in the future havent earned one.

H.W. Lewis

With investors averse to losses and ambiguity, and the last

decades two bear markets and hard-to-predict events such as

overthrown governments in the Middle East and natural

disasters still fresh in mind, it is not hard to understand why

many are apprehensive about the risks involved in investing in

stocks and instead choose to stay in cash. This may be a

mistake. First, while cash may seem like a riskless investment,

it is only so in nominal terms. Prices are slowly creeping up,

eroding consumers purchasing power. The current US ination

rate of 1.8% translates to a price increase of 50% in about two

decades, decreasing purchasing power by a third.

Second, while a belief in another potential recession may

justify staying out of equities for a period of time, market timing

is extremely difcult, with gains often accumulating unpredict-

ably, and concentrated on a few trading days. For example, if

an investor had missed just the rst 20% of the market

recovery in 2003, he or she would have underperformed those

who stayed invested throughout the downturn and recovery by

nearly 10%, assuming an investment period from March 2000

to February 2006.

Here are three steps to take that can mitigate the impact of

behavioral biases and non-standard preferences on long-term

investment performance:

Take the plunge: While loss aversion may be a well-document-

ed and persistent human trait, its impact on investment choice

and performance only really becomes detrimental when

combined with the habit of narrow framing

29

. To consciously

tackle these biases, we would recommend investors broaden

their concept of invested wealth to include not only stocks and

bonds, but also income-producing assets such as businesses

and real estate, expected future wealth from employment

income, and personal property such as houses, cars and

artwork. While any wealth category may suffer losses in a given

period of time, when assets are not perfectly correlated, other

wealth categories are likely to help offset these losses. Stock

market investments may seem more appealing and less like

isolated gambles when considered in this broader overall

portfolio diversication context.

23

Barber, B. and Odean, T. (April 2000) Trading is Hazardous to Your Wealth: The

Common Stock Investment Performance of Individual Investors, Journal of Finance, Vol.

LV, No. 2, 773-806.

24

Barber, B. and Odean, T. (March 2002) Online Investors: Do the Slow Die First?

Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2, 455-487.

25

Barber, B. and Odean, T. (February 2001) Boys will be Boys: Gender, Overcondence,

and Common Stock Investment, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 116, No. 1, 261-

292.

26

Barber, B. and Odean, T. (2008) All that Glitters: The Effect of Attention and News

on the Buying Behavior of Individual and Institutional Investors, Review of Financial

Studies, Vol. 21, 2, 785-818.

27

Benartzi, S. (2001) Excessive Extrapolation and the Allocation of 401(k) Accounts to

Company Stock, Journal of Finance, 56.5, 1747-1764.

28

Odean, T. (1998) Are investors reluctant to realize their losses? Journal of Finance,

53.5, 1775-1798.

29

Barberis, N., Huang, M. and Thaler R. (2006) Individual Preferences, Monetary

Gambles, and Stock Market Participation: A Case for Narrow Framing, American

Economic Review 96, 1069-1090.

i S H A R E S MA R K E T P E R S P E C T I V E S [ 8 ]

unnecessary portfolio concentration resulting from the 1/n rule

or home country bias. One way of doing this is by investing in

well-diversifed mutual funds or ETFs. The chosen investment

strategy should also reect the individuals personal risk

tolerance and investment horizon. These targets may be more

easily maintained through market uctuations by investing in

well-diversied managed funds, such as lifestyle funds that

target a specied level of risk, or target date funds where the

risk level is selected based on the number of years left until

retirement, e.g., higher risk, more aggressive portfolios heavily

invested in equities for younger workers.

For example, BlackRock provides ve long-term strategic asset

allocation models with different risk-return objectives. The

moderate risk fund allocations are depicted in Figure 2 and

relative to the average individual investors portfolio choices,

provide a high degree of diversication, with 53% invested in

xed income, 21% in US equities, 20% in international equities

and 5% in non-traditional asset classes, easily implemented

with only 10 already diversifed iShares ETFs.

As individual investors have shown to be particularly prone to

cognitive errors, tactical market positioning around the long-term

allocation may be better left to experienced investment professionals

dedicated to the task. For example, the BlackRock Model Portfolio

Solutions Group offers a series of outcome-oriented and tactical

model portfolios implemented with iShares ETFs and BlackRock

mutual funds to help clients gain access to income or tactical market

views efciently. These models use a rigorous process to manage

portfolio level risks, taking into account not only an assets size but

also its riskiness when deciding its weight in a portfolio, and are

therefore well-positioned to help deliver better long-term risk-ad-

justed returns than simple market capitalization-weighted indices.

We would also advocate that investors position their core

portfolio holdings for the longer term, and only evaluate them

periodically rather than continuously. While stock markets can

be highly volatile over short horizons, increasing investor

discomfort around potential losses, time has tended to smooth

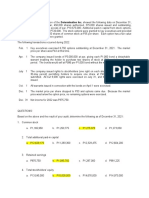

out uctuations. Figure 1 shows the worst returns in annualized

terms over the past 25 years of the MSCI All Country World Index

as a broad global equity market benchmark, the S&P 500 Index

as a broad US equity market benchmark and the Barclays

Capital Aggregate Bond Index as a broad US xed income

benchmark based on different return horizons. For example,

while the worst annualized monthly return of the S&P 500 Index

during the period was -203%, this improved to -45% for annual

returns, -4.1% for 10-year returns and 7.6% for 20-year returns.

Additionally, portfolio construction techniques to minimize

overall fund volatility, possibly packaged into exchange traded

funds such as the iShares MSCI All Country World Minimum

Volatility Index Fund (ACWV), tend to provide downside protec-

tion in volatile markets and may help increase investor comfort

around investing in risky assets.

When it comes to retirement savings, automatic enrollment and

sensible default contribution rates, together with automatic

savings increases at the time of pay increases, have been shown

to effectively counteract investor inertia, loss aversion and

self-control issues, leading to increased participation rates and

savings. The sensitivity of the chosen retirement investment

allocations to the way the options are framed underlines the

importance of overall plan design.

30

Diversify, diversify, diversify: We advocate that investors

implement a long-term baseline allocation that is diversied

across US and international equities, xed income and non-tra-

ditional asset classes such as commodities, revisiting any

US Fixed Income 31.10%

High Yield 5.00%

International Treasury Bond 7.30%

TIPS 10.00%

US Equities 21.40%

Emerging Markets 5.20%

Developed Markets ex-US 14.70%

Commodity 3.00%

Gold 0.40%

Reits 1.90%

Figure 2: BlackRock Strategic Models - Moderate Allocation

30

Benartzi, S. and Thaler, R. H. (Summer 2007) Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Savings

Behavior, Journal of Economic Perspectives. Source: Bloomberg, as of 12/21/12.

1 month 6 months 12 months 3 month 5 years 3 years 10 years 20 years

MSCI ACWI Barclays Agg S&P 500

-250%

-200%

-150%

-100%

-50%

0%

50%

Figure 1: Worst Annualized Return by Horizon

i S H A R E S MA R K E T P E R S P E C T I V E S [ 9 ]

When picking a nancial advisor or a mutual fund, it helps to be

patient and, if possible, evaluate performance over several years

relative to agreed-upon objectives, rather than extrapolating on

a short history of returns, possibly cutting a fund due to a recent

blip in performance despite its consistent outperformance over

the longer horizon.

Rebalance: To ensure that a portfolios allocations remain in the

target range, we recommend that it be rebalanced on schedule,

e.g., quarterly or semi-annually, or once allocations have moved

away from the target by a predetermined percentage. Some

investors succumb to inertia and forego timely rebalancing,

while others trade excessively, which may lead to any invest-

ment prots getting eaten up by trading costs. When available,

it may be in fact helpful to set up automatic rebalancing,

although any retirement plan options such as the funds avail-

able should still be reviewed periodically.

When investments are actively evaluated and selected, the

focus should be on future expected returns, rather than past

performance. Behavioral biases may be mitigated by a rules-

based or systematic investment approach, such as investment

models built to predict fair asset values, quantitative screens

to sift through investments with ex-ante thresholds to ag

opportunities, or systematic checklists with comprehensive sets

of questions. Many systematic funds in fact attempt to exploit

known market anomalies that have possibly arisen for behavioral

reasons, such as the post-earnings announcement drift (share

prices continuing to drift in the direction of an initial jump after

corporate announcements such as large earnings or dividend

changes), or price momentum (stocks that have outperformed

over a period of six months continuing to outperform for the next

six to twelve months). Stop-loss rules may soften the impact of

individual investors general reluctance to realize losses, leading

to increased selling of losing investments and harvesting of capital

losses to minimize tax burden.

Conclusion

I know you think you understand what you thought I said but Im not

sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant.

Alan Greenspan

Financial markets operate around the knowledge, perceptions,

judgments and biases of its participants, often backed by messy

real-life decisions made amidst incomplete information and

uncertainty. To better understand actual observed investor

behavior and to help shed light on to market anomalies that have

been difcult to explain under the traditional assumptions of full

rationality and market efciency, behavioral nance incorporates

insights from human psychology. In the real world, people are less

than rational, suffer from inertia, have limited cognitive abilities,

focus excessively on the short term with a high degree of aversion

to losses, and are overcondent in their own prospects.

As a result of these biases, individual investors have been

found to shun the stock market, hold excessively concentrated

portfolios of companies they are familiar with, and trade too

much. Certain parts of the population have been found to be

particularly prone to given biases. For example, men tend to

be especially condent in their own abilities and succumb to

portfolio losses from excessive trading. The performance impact

of these biases can be signicant, especially if they result in

portfolio exposures that are ill suited for a given individuals

nancial goals.

Understanding behavioral biases and attempting to mitigate

their impact on investment performance through rules-based

or systematic strategies may be especially important amidst

todays increased economic uncertainty and market volatility.

The ongoing deleveraging in developed markets has raised

overall macroeconomic instability, as seen with higher growth

and ination volatility. This has not been helped by the often

erratic politics and policy making in countries with structural

imbalances and need for reform. While suboptimal investment

choices resulting from cognitive errors may not have mattered

much in a secular bull market such as during the 1990s, today

when companies and entire countries hang on the lifeline of

central banks and other countries angry voters, biases such as

individual investors general reluctance to realize losses may

cause some serious havoc on portfolio performance.

i

S

-

8

9

3

2

-

0

1

1

3

Carefully consider the iShares Funds investment objectives, risk factors, and

charges and expenses before investing. This and other information can be

found in the Funds prospectuses, which may be obtained by calling

1-800-iShares (1-800-474-2737) or by visiting www.iShares.com. Read the

prospectus carefully before investing.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. Diversication may not

protect against market risk. In addition to the normal risks associated with investing,

international investments may involve risk of capital loss from unfavorable uctuation in

currency values, from differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from

economic or political instability in other nations. The iShares Minimum Volatility Funds may

experience more than minimum volatility as there is no guarantee that the underlying indexs

strategy of seeking to lower volatility will be successful.

Index returns are for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual iShares Fund

performance. Index performance returns do not reect any management fees,

transaction costs or expenses. Indexes are unmanaged and one cannot invest directly in

an index. Past performance does not guarantee future results. For actual iShares Fund

performance, please visit www.iShares.com or request a prospectus by calling 1-800-iShares

(1-800-474-2737).

The iShares Funds that are registered with the US Securities and Exchange Commission under

the Investment Company Act of 1940 (Funds) are distributed in the US by BlackRock

Investments, LLC (together with its afliates, BlackRock). This material is solely for educational

purposes and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy

any shares of any fund (nor shall any such shares be offered or sold to any person) in any

jurisdiction in which an offer, solicitation, purchase or sale would be unlawful under the securities

law of that jurisdiction.

This material is solely for educational purposes and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to

sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any shares of any fund (nor shall any such shares be offered

or sold to any person) in any jurisdiction in which an offer, solicitation, purchase or sale would be

unlawful under the securities law of that jurisdiction.

In Latin America, for Institutional and Professional Investors Only (Not for public Distribution):

If any funds are mentioned or inferred to in this material, it is possible that some or all of the funds

have not been registered with the securities regulator of Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru,

Uruguay or any other securities regulator in any Latin American country, and thus might not be

publicly offered within any such country. The securities regulators of such countries have not

conrmed the accuracy of any information contained herein. No information discussed herein can

be provided to the general public in Latin America.

In Hong Kong, this document is issued by BlackRock (Hong Kong) Limited for Institutional

Investors only and has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong

Kong. In Singapore this is issued by BlackRock (Singapore) Limited (Co. registration no.

200010143N) for Institutional Investors only.

Notice to residents in Australia:

FOR WHOLESALE CLIENTS AND PROFESSIONAL INVESTORS ONLY NOT FOR

PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION

Issued in Australia by BlackRock Investment Management (Australia) Limited ABN 13 006 165

975, AFSL 230523 (BlackRock). This information is provided for wholesale clients and

professional investors only. Before investing in an iShares exchange traded fund, you should

carefully consider whether such products are appropriate for you, read the applicable prospectus

or product disclosure statement available at iShares.com.au and consult an investment adviser.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Investing involves risk including

loss of principal. No guarantee as to the capital value of investments nor future returns is made

by BlackRock or any company in the BlackRock group. Recipients of this document must not

distribute copies of the document to third parties. This information is indicative, subject to change,

and has been prepared for informational or educational purposes only. No warranty of accuracy

or reliability is given and no responsibility arising in any way for errors or omissions (including

responsibility to any person by reason of negligence) is accepted by BlackRock. No representation

or guarantee whatsoever, express or implied, is made to any person regarding this information.

This information is general in nature and has been prepared without taking into account any

individuals objectives, nancial situation, or needs. You should seek independent professional

legal, nancial, taxation, and/or other professional advice before making an investment decision

regarding the iShares funds. An iShares fund is not sponsored, endorsed, issued, sold or

promoted by the provider of the index which a particular iShares fund seeks to track. No index

provider makes any representation regarding the advisability of investing in the iShares funds.

Notice to investors in New Zealand:

FOR WHOLESALE CLIENTS ONLY NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION

This material is being distributed in New Zealand by BlackRock Investment Management

(Australia) Limited ABN 13 006 165 975, AFSL 230523 (BlackRock). In New Zealand, this

information is provided for registered nancial service providers and other wholesale clients only

in that capacity, and is not provided for New Zealand retail clients as dened under the Financial

Advisers Act 2008. BlackRock does not offer interests in iShares to the public in New Zealand,

and this material does not constitute or relate to such an offer. Before investing in an iShares

exchange traded fund, you should carefully consider whether such products are appropriate for

you, read the applicable prospectus or product disclosure statement available at iShares.com.au

and consult an investment adviser. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future

performance. Investing involves risk including loss of principal. No guarantee as to the capital

value of investments nor future returns is made by BlackRock or any company in the BlackRock

group. Recipients of this document must not distribute copies of the document to third parties.

This information is indicative, subject to change, and has been prepared for informational or

educational purposes only. No warranty of accuracy or reliability is given and no responsibility

arising in any way for errors or omissions (including responsibility to any person by reason of

negligence) is accepted by BlackRock. No representation or guarantee whatsoever, express or

implied, is made to any person regarding this information. This information is general in nature

and has been prepared without taking into account any individuals objectives, nancial situation,

or needs. You should seek independent professional legal, nancial, taxation, and/or other

professional advice before making an investment decision regarding the iShares funds. An

iShares fund is not sponsored, endorsed, issued, sold or promoted by the provider of the index

which a particular iShares fund seeks to track. No index provider makes any representation

regarding the advisability of investing in the iShares funds.

The strategies discussed are strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and should not be

construed as a recommendation to purchase or sell, or an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer

to buy any security. There is no guarantee that any strategies discussed will be effective. The

information provided is not intended to be a complete analysis of every material fact respecting

any strategy. The examples presented do not take into consideration commissions, tax

implications or other transactions costs, which may signicantly affect the economic

consequences of a given strategy.

This material represents an assessment of the market environment at a specic time and is not

intended to be a forecast of future events or a guarantee of future results. This information should

not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding the funds or any

security in particular.

2013 BlackRock, Inc. All rights reserved. iSHARES and BLACKROCK are registered and

unregistered trademarks of BlackRock, Inc. or its subsidiaries in the United States and

elsewhere. All other marks are the property of their respective owners.

iS-8932-0113 5175-07RB-01/13

Not FDIC Insured No Bank Guarantee May Lose Value

For more information visit www.iShares.com

or call 1-800-474-2737

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Mba ThesisDocument49 paginiMba Thesisk.shaikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Invertor So&economic Ckaracterfa A: On Rirk TMD Return Prefer - H. Kent Baker. Georgetown IlniyersiqyDocument8 paginiInvertor So&economic Ckaracterfa A: On Rirk TMD Return Prefer - H. Kent Baker. Georgetown IlniyersiqyArslan ZafarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teshildar (BS-16)Document1 paginăTeshildar (BS-16)Arslan ZafarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teshildar (BS-16)Document1 paginăTeshildar (BS-16)Arslan ZafarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pci BbsydpDocument29 paginiPci BbsydpArslan ZafarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Energy CrisisDocument2 paginiEnergy CrisisArslan ZafarÎncă nu există evaluări

- ProjectDocument33 paginiProjectArslan ZafarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- 2014 12 Mercer Risk Premia Investing From The Traditional To Alternatives PDFDocument20 pagini2014 12 Mercer Risk Premia Investing From The Traditional To Alternatives PDFArnaud AmatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Management Surveillance at Ludhiana Stock ExchangeDocument99 paginiRisk Management Surveillance at Ludhiana Stock Exchangepritpal singhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparative Study On Cryptocurrency and Stock MarketDocument13 paginiComparative Study On Cryptocurrency and Stock MarketAllan GeorgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elliott Wave Theory BasicsDocument7 paginiElliott Wave Theory BasicsSarat KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- QuestionsDocument3 paginiQuestionslois martinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial Ratio Analysis GuideDocument30 paginiFinancial Ratio Analysis GuideJohn Mark CabrejasÎncă nu există evaluări

- GP - Consumer Behaviour For Third Party Products at Private BanksDocument75 paginiGP - Consumer Behaviour For Third Party Products at Private Banksjignay100% (4)

- Football Field MYOR-2Document27 paginiFootball Field MYOR-2Nusan TravellerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nick Train The King of Buy and Hold PDFDocument13 paginiNick Train The King of Buy and Hold PDFJohn Hadriano Mellon FundÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Management Project - Risk Analysis of StocksDocument33 paginiRisk Management Project - Risk Analysis of StocksPrajwal Vemala JagadeeshwaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Investing money options and stock market indexesDocument2 paginiInvesting money options and stock market indexesSeptian Pajrin MuktiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basics of Share MarketDocument222 paginiBasics of Share Marketbk_a1Încă nu există evaluări

- Study On MVMFDocument60 paginiStudy On MVMFManîsh SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macroeconomic Factors and The Indian Stock Market: Exploring Long and Short Run RelationshipsDocument14 paginiMacroeconomic Factors and The Indian Stock Market: Exploring Long and Short Run Relationshipsaurorashiva1Încă nu există evaluări

- Perception of Investors Towards Indian Commodity Derivative Market With Inferential Analysis in Chennai CityDocument10 paginiPerception of Investors Towards Indian Commodity Derivative Market With Inferential Analysis in Chennai CitySanjay KamathÎncă nu există evaluări

- State Street Global Advisors Global Market Outlook 2022Document29 paginiState Street Global Advisors Global Market Outlook 2022Email Sampah KucipÎncă nu există evaluări

- February StatementDocument16 paginiFebruary Statementrangaswamy8194Încă nu există evaluări

- Screening For Stocks Using The Dividend Adjusted Peg RatioDocument6 paginiScreening For Stocks Using The Dividend Adjusted Peg RatioHari PrasadÎncă nu există evaluări

- McDonald's Stock Clearly Benefits From Its Large Buybacks - Here Is Why (NYSE - MCD) - Seeking AlphaDocument12 paginiMcDonald's Stock Clearly Benefits From Its Large Buybacks - Here Is Why (NYSE - MCD) - Seeking AlphaWaleed TariqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complete Guide To Value InvestingDocument43 paginiComplete Guide To Value Investingsantoshpinge3417Încă nu există evaluări

- MITOCW - 10. Financial System Challenges & OpportunitiesDocument32 paginiMITOCW - 10. Financial System Challenges & OpportunitiesAnjali AhujaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MulnDocument88 paginiMulnASDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Methodology Index MathDocument71 paginiMethodology Index MathGaurav VermaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shining The Light On Short InterestDocument13 paginiShining The Light On Short InterestjramongvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparing Takeover Laws in UK, India & SingaporeDocument31 paginiComparing Takeover Laws in UK, India & SingaporeAnuj BalajiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Depository Receipts: Presented By-Vikash Sharma (51) Ruchi BangaDocument12 paginiDepository Receipts: Presented By-Vikash Sharma (51) Ruchi Bangasuraj kumar0% (1)

- AI Assignment 2Document8 paginiAI Assignment 2Fareeha SumairÎncă nu există evaluări

- Olympic vs Quasem Financial AnalysisDocument39 paginiOlympic vs Quasem Financial AnalysisRafi Ahmêd0% (1)

- (R13) China Deloitte CN LSHC Medical Device White Paper en 210301Document24 pagini(R13) China Deloitte CN LSHC Medical Device White Paper en 210301lethebinh3Încă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Managerial Finance: Fifteenth Edition, Global EditionDocument22 paginiPrinciples of Managerial Finance: Fifteenth Edition, Global Editionpatrecia 18960% (1)