Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Islamic School of Law Evolution, Devolution, and Progress. Edited by Peri Bearman, Rudolph Peters, Frank Vogel - Muhammad Qasim Zaman PDF

Încărcat de

Ahmed Abdul GhaniTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Islamic School of Law Evolution, Devolution, and Progress. Edited by Peri Bearman, Rudolph Peters, Frank Vogel - Muhammad Qasim Zaman PDF

Încărcat de

Ahmed Abdul GhaniDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Book Reviews / Islamic Law and Society 16 (2009) 95-111

101

e Islamic School of Law: Evolution, Devolution, and Progress. Edited by Peri Bearman, Rudolph Peters, Frank Vogel. Harvard Series in Islamic Law, 2. Cambridge, MA: Islamic Legal Studies Program, Harvard Law School. Distributed by Harvard University Press, 2005. Pp. xvii + 300. ISBN 0-674-01784-6. $39.95. is collection of essays represents an important contribution to the study of a central Islamic institution, the madhhab or school of law, in pre-modern and modern Islam.1 e chapters range from legal developments in the 2nd/8th century to the present and, in geographical terms, from the Middle East and Central Asia to Spain, on the one hand, and Indonesia, on the other. Most of the attention is devoted to the Sunn schools of law, though there is a chapter on the hirs of al-Andalus and one on the late classical Imm Sha. e volume also provides a substantial discussion of how the madhhab has fared in modern Islam. Peri Bearman and Frank Vogel begin the book with a brief overview of the evolution of the madhhab, followed by an account, by Bernard Weiss, of conceptions and forms of authority in Islamic legal theory. As Weiss observes, pre-modern scholars tended to view the madhhab as a body of doctrine articulated by master jurists (mujtahids), with the understanding that all thoseboth jurists and lay peoplewho were themselves incapable of toiling over the authoritative texts needed to follow (taqld) those who had demonstrated such an ability. is view had intellectual as well as social consequences. e fact that only the few can be mujtahids and that many must be their followers sets up a hierarchy of roles that is fundamental to Muslim thinking about the place of the mujtahid within the social order and represents an important rst step in the containment of disorder in the law (p. 3). But if recognizing the authority of the master jurists was crucial to the development and coherence of the legal tradition, it scarcely precluded continuing advances in legal thought, not infrequently in the form of explicit disagreement with earlier views. In his excellent study of the anaf madhhab as it existed in the 4th/10th century, Eyyup Kaya draws attention to the existence of signicant regional variation among anaf scholars based in Iraq, Balkh, and Bukhara. ese scholars and their followers frequently privileged the doctrines that had developed within their geographical centers over those from other anaf locales, and it was not uncommon for them to diverge even from the opinions of the schools founding fathers. is regional variation raises the question, of course, of whether one can legitimately speak of a anaf madhhab at this time. Kaya answers it in the armative, arguing that a anaf identity had come to consist in continuous scholarly engagement with the juristic past. ere are anafs such as al-Karkh who rejected the typical opinions of Ab anfa, Kaya writes, or those, such as Abul-Qsim al-ar of 10th-century Balkh, who disagreed with Ab anfa on thousands of

1)

e term madhhab is not italicized in this volume, and this review follows it in this convention.

DOI: 10.1163/156851908X413784

Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009

102

Book Reviews / Islamic Law and Society 16 (2009) 95-111

issues, but there was not one anaf who did not take the anaf juristic tradition as a legal source (p. 39). A similar point is made by Robert Gleave in his discussion of how the late classical Imm jurists viewed their own madhhab. e Imm legal tradition is, like others, cumulative, with the jurists not only adhering to the doctrines handed down to them from earlier authorities but also continuing to sift through them, striving to resolve their ambiguities, and arguing over how to rank and reorganize them in relation to one another. As in any traditional culture, a great deal of the scholarly acumen was seen to consist in navigating the complexities of this tradition while adapting it to new imperatives. Even ijtihd, which had a considerably richer history in pre-modern Imm law than it didat least in terms of formal claims to itin contemporaneous Sunn circles, was a matter not of bypassing this inherited tradition but of delving deeper into it. Indeed, as Gleave observes, a major part of the mujtahid s knowledge [was recognized to consist] of bibliographic skills (p. 136; emphasis added). Gleave also argues that, for all their criticism of the Ul jurists and of their ijtihd, the Akhbrs, who sought to base their views directly on the teachings of the Prophet and the imms, also showed considerable reverence for many earlier jurists and continued to engage with their work. In this sense, the Akhbrs, too, were part of the Imm legal tradition. And inasmuch as it is this juristic past that constituted a madhhab, even the Akhbrs were not anti-madhhab, as they are sometimes characterized. A number of essays in this collection attend not only to how a madhhab evolved in terms of doctrine, but also to the social and political contexts in which it did so. Examining the Umayyad madhhab of al-Awz (d. 157/774) and Sufyn al-awr (161/778), Steven Judd argues that its demise had much to do with the rise of the Abbsids, the dynasty that replaced the Umayyads in 132/750. Al-Awz came to have reasonably good relations with Abbsid authorities whereas al-awr died while in hiding from them. While these two gures had shared much in terms of their legal approach, their contrasting political trajectories posed problems for their followers, accentuated by their having to decidein line with evolving conceptions of a madhhab as being rooted in the doctrines of an eponymous gurewhether one followed al-Awz or al-awr. Judds broader argument is that the early history of this and other madhhabs is best studied not with reference to the neat but often misleading regional and eponymous paradigms [but rather by] simply asking who associated with whom and what views and loyalties these circles of scholars shared (p. 25). Unsurprisingly, even the madhhabs that turned out to be successful in the long run had uncertain beginnings and long exhibited considerable uidity in their relations with other evolving schools. e development of the institution of the madrasa may have helped consolidate school boundaries in some measure, as Daphna Ephrat suggests in her study on 5th/11th century Baghdad. Yet as Daniella Talmon-Heller shows in her study of 6th/12th-7th/13th century Syria, these boundaries were anything but impermeable and delity to the madhhab often

Book Reviews / Islamic Law and Society 16 (2009) 95-111

103

competed with other loyaltiesethnic, political, and geographic, among others (cf. pp. 108, 114). Alfonso Carmona meticulously delineates the slow and uneven dissemination of the writings of Mlik b. Anas and his students in al-Andalus, and Maribel Fierro shows that it was only in the 4th/10th century, when Mlik legal scholars had become well-entrenched in the Iberian peninsula, that the image of al-Andalus as having been Mlik since Mliks times began to be built (p. 61). ough she arrives at her conclusions quite dierently from the hir scholar Ibn azm (d. 456/1064), she ultimately concurs with him on the major role Umayyad patronage played in the success of the Mlik madhhab in al-Andalus (pp. 67-70). It is a measure of the state-sponsored hegemony of the Mliks that, in the relatively few instances that they served as judges, even the hirs (discussed in this volume by Camilla Adang) were expected to rule according to the norms of the Mlik madhhab. If royal patronage contributed signicantly to the fortunes of some schools of law, developments within a madhhab could, in turn, also position it well for ocial recognition. In an important contribution to this volume, Rudolph Peters shows that anasm was able to play the role of an ocial madhhab under the Ottomans in part because, between the 6th/12th and the 11th/17th centuries, anaf law had come to be increasingly standardized with a relatively clear delineation of what opinions were to be deemed the most authoritative. anaf works such as Ibrhm al-alabs (d. 956/1549) Multaq al-abur and Muammad Shaykhzdes (d. 1078/1667) commentary on it, the Majma al-anhur, were especially inuential compendia of the standard doctrine in Ottoman lands. e existence of such handbooks made it possible for the Ottomans to rationalize judicial administration in their realm, both by giving ocial recognition to what the anaf legal circles had themselves come to see as their authoritative norms and by stipulating that particular anaf doctrines be followed to the exclusion of certain others. Signicantly, as Peters shows, some of the sultans decrees to this eect also made their way into the anaf legal handbooks. is illustrates not only the symbiotic relationship between Ottoman judicial practice and the anaf madhhab but also the fact that, even in an age of taqld and standardized texts, the legal tradition continued to adapt itself to new pressures and needs. ough Peters does not raise this question, it would be illuminating to examine how the standardization of anaf doctrine under the Ottomans might compare with the career of anasm elsewhere. For instance, the 11th/17th century Fatw Alamgriyya (often called al-Fatw al-Hindiyya), produced under the patronage of the Mughal emperor Awrangzeb lamgr (r. 1068-1118/1658-1707), had also sought to rationalize judicial practice in Mughal India.2 Quite apart from the

2)

Cf. al-Fatw al-Hindiyya f madhhab al-imm al-aam Ab anfa al-Numn, 6 vols. (Beirut, n.d. [1973; reprint of the Bulaq edition, 1310 A.H.]), 1:2-3; also cf. Sq Mustaidd Khn, Mathir-i lamgr, ed. A.A. Al (Osnabrck, 1985; reprint of the Calcutta 1870-73 edition), 529-30.

104

Book Reviews / Islamic Law and Society 16 (2009) 95-111

question of its actual impact,3 it is worth noting that this compendium of anaf norms gives extensive coverage to the broad range of juristic disagreement that the school tradition had come to recognize by this time. is suggests not only that Mughal judges would have continued to enjoy considerable room for maneuver in drawing on their internally variegated legal tradition but also that the standardization of anaf doctrine may have meant somewhat dierent things in dierent contemporaneous regions. How the institution of the madhhab has fared in conditions of modernity is a question crucial for an understanding of issues of religious authority in the modern world. e contributors to this volume seem to concur that the madhhab does not have much of a future in Islam. Brinkley Messick analyzes a fatwa issued at the turn of the 20th century by a Sh mufti of Singapore on the question of whether it was permissible for Muslims to have their merchandise on European ships insured with non-Muslim insurance companies. ough he ultimately ruled in favor of such insurance, the Sh mufti had not found any clear answer in his own madhhab and had turned, inter alia, to the work of Ibn bidn, the celebrated 19th-century anaf jurist of Damascus, for guidance. e Sh muftis fatwa was then sent to Muammad Rashd Ri (d. 1935), the Salaf journalist-scholar whose inuential journal, al-Manr, carried a regular section devoted to addressing requests for fatwas from across the Muslim world. In formulating his own opinion on this questionwhich was also in favor of such insurance, though on grounds dierent from those on which the Sh mufti had arguedRi drew on the resources of the Islamic legal tradition as a whole, showing himself to be attentive to general considerations of the common good rather than to the norms and methods of any particular madhhab. As Messick sees it, Ris approach, along with the course of action the Sh mufti had adopted, presaged the madhhabs declining fortunes in the modern world. Nor is it only in the face of new questions that many a jurist has been impelled to step beyond his madhhab. Other, often stronger, forces have also been at work. e nation-state has had its own claims to legislation and to the codication of the law; and even when such legislation professes to be guided by the spirit of Islam or by resources from the Islamic legal tradition, it is seldom the doctrinal legacy of any single madhhab that has guided such legislation. In Indonesia, for instance, as discussed by Mark Cammack, there have been persistent calls for the development of an Indonesian madhhab, though the question of precisely what this would entail remains unsettled. If the nation-state has continued to tear at the seams of the madhhab, so have globalization and the new information and communication technologies that go with it. In recent decades, as Ihsan Yilmaz argues in his account of inter-madhhab surng, the boundaries of the madhhab have reached the point of dissolution as countless micro-mujtahids have taken

3)

For one view on this question, see Muzaar Alam, e Languages of Political Islam: India 1200-1800 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 13.

Book Reviews / Islamic Law and Society 16 (2009) 95-111

105

it upon themselves to nd or provide answers to their questions by, inter alia, drawing indiscriminately on whatever legal opinions are accessible to them and by going back to the foundational Islamic texts for unmediated guidance. Yet, contrary to the sense that emerges from this volume, it is probably premature to write the obituary of the madhhab. If the madhhab has fared poorly in many places, it has also retained considerable vitality in others. Oddly, there is no chapter in this volume on South Asia, a region that houses nearly a third of the worlds Muslim population. ough the anaf madhhab, adhered to by the overwhelming proportion of South Asian Muslims, has undergone signicant changes in colonial and post-colonial times, it is anything but clear that this school of law is on its way to dissolution. On the contrary, anaf scholarship of a strongly partisan color has continued to thrive in circles of ulam, especially those belonging to the Deoband doctrinal orientation.4 A good deal of this scholarship has been produced in response to the Ahl-i adth of India, a Salaf movement whose adherents reject the authority of the schools of law and insist on basing themselves directly on the Qurn and the adth. e I l al-sunan, a twenty-one volume commentary on adth-reports with a primarily legal content, was, for instance, written by a anaf-Deoband scholar to help answer the Ahl-i adth allegation that anaf norms have a rather tenuous basis in adth.5 Yet the scope of anaf scholarship extends beyond the Ahl-i adth challenge, illustrating something of the continuing strength of the anaf school in the Indian subcontinent. Like Singapores Sh mufti discussed by Messick, South Asias anaf scholars have also, on occasion, had to step outside their school tradition.6 In many instances, the ulam have had little choice but to go along with state-sponsored legislative initiatives that have little to do with any madhhab methods or boundaries. Nor are all anaf ulam of contemporary South Asia committed to the regimen of taqld in quite the same way. Indeed, some have become increasingly open to certain forms of ijtihd. is is the case, for instance, with Indias Islamic Fiqh Academy (founded in 1989), which advocates the need for a collective ijtihd as a way of meeting some of the problems facing the Muslims of India. Even so, many of those associated with this institution retain a strong commitment to the

On the history and politics of the Deobandi doctrinal orientation, see Barbara D. Metcalf, Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860-1900 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982); Muhammad Qasim Zaman, e Ulama in Contemporary Islam: Custodians of Change (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002). 5) afar Amad Uthmn, I l al-sunan, ed. zim al-Q, 21 vols. (Beirut: Dr al-kutub al-ilmiyya, 1997). 6) Cf. Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Ashraf Ali anaw: Islam in Modern South Asia (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2008), 57-65.

4)

106

Book Reviews / Islamic Law and Society 16 (2009) 95-111

anaf madhhab;7 some even profess to see Ab anfa himself as the forbear of collective ijtihd.8 Others are considerably more ambivalent about self-consciously embracing the language of ijtihd. Yet professions of taqld do not necessarily preclude possibilities of legal change, any more than they did among earlier generations of putatively taqld-bound scholars. e point here is not, of course, to dispute the decline of the madhhab in particular contexts (Indias Fiqh Academy itself might well contribute to that decline in the Indian milieu), but to note, rather, that this complex institution continues to follow varied trajectories and that contemporary eorts to rethink legal norms with reference to the madhhab deserve no less attention than do signs of the madhhabs dissolution.9 at modernity itself is best spoken of in the plural, with its diering frames and diering paces, as Messick aptly puts it (p. 161), suggests as much. e precise implications of such dierences, so far as the madhhab and questions of religious authority are concerned, merit much further study. is volume represents a commendable step in that direction. Muhammad Qasim Zaman Princeton University

Cf. Mujhid al-Islm al-Qsim, al-Ijtihd al-ijtim, in Mujhid al-Islm al-Qsim, ed., Buth qhiyya min al-Hind (Beirut: Dr al-kutub al-ilmiyya, 2003), 6-8. al-Qsim (d. 2002), the founding president of the Islamic Fiqh Academy, was a leading Deoband scholar. e current president of the Academy, afr al-Dn Mift, also serves as the chief mufti of the Deoband madrasa. 8) Cf. Muammad Fahm Akhtar Nadw, Tp ke shahr Mysore main Islmic Fiqh Academy India k pandarahwn qh seminar, Tarjumn-i Dr al-Ulm (Delhi), vol. 2, nos. 8-9 (April-May, 2006), 71, 73. 9) For an example of such rethinking in contemporary Indonesia, cf. R. Michael Feener, Muslim Legal ought in Modern Indonesia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 167.

7)

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Intellectual Achievements of Early Muslim CommunitiesDe la EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Intellectual Achievements of Early Muslim CommunitiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parable and Politics in Early Islamic History: The Rashidun CaliphsDe la EverandParable and Politics in Early Islamic History: The Rashidun CaliphsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Between Metaphor and Context: The Nature of The Fatimid Ismaili Discourse On Justice and InjusticeDocument7 paginiBetween Metaphor and Context: The Nature of The Fatimid Ismaili Discourse On Justice and InjusticeShahid.Khan1982Încă nu există evaluări

- Oxford Handbook of Islamic Law The Class PDFDocument35 paginiOxford Handbook of Islamic Law The Class PDFjawadkhan2010100% (1)

- Avicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyDe la EverandAvicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European ImaginationDe la EverandSaracens: Islam in the Medieval European ImaginationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Everyday Islamic Law and the Making of Modern South AsiaDe la EverandEveryday Islamic Law and the Making of Modern South AsiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Imam of the Christians: The World of Dionysius of Tel-Mahre, c. 750–850De la EverandThe Imam of the Christians: The World of Dionysius of Tel-Mahre, c. 750–850Încă nu există evaluări

- Islamic Thought: From Mohammed to September 11, 2001De la EverandIslamic Thought: From Mohammed to September 11, 2001Încă nu există evaluări

- The Amir: The Umayyads Vs the Abbasids and Their Successors the WahhabisDe la EverandThe Amir: The Umayyads Vs the Abbasids and Their Successors the WahhabisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Violence and Genocide in Kurdish Memory: Exploring the Remembrance of the Armenian Genocide through Life StoriesDe la EverandViolence and Genocide in Kurdish Memory: Exploring the Remembrance of the Armenian Genocide through Life StoriesÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Mar Yahballaha and Rabban Sauma: Edited, translated, and annotated by Pier Giorgio BorboneDe la EverandHistory of Mar Yahballaha and Rabban Sauma: Edited, translated, and annotated by Pier Giorgio BorboneÎncă nu există evaluări

- 05 Sanders - Robes of Honor in Fatimid EgyptDocument15 pagini05 Sanders - Robes of Honor in Fatimid Egypttawwoo100% (1)

- Ahmad ibn Tulun: Governor of Abbasid Egypt, 868–884De la EverandAhmad ibn Tulun: Governor of Abbasid Egypt, 868–884Încă nu există evaluări

- Fletcher (Madeleine) - The Almohad Tawhīd - Theology Which Relies On LogicDocument19 paginiFletcher (Madeleine) - The Almohad Tawhīd - Theology Which Relies On LogicJean-Pierre MolénatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reorienting the East: Jewish Travelers to the Medieval Muslim WorldDe la EverandReorienting the East: Jewish Travelers to the Medieval Muslim WorldÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Different Perspective: The Traveler's Guide to Medieval (Islamic) Spain and PortugalDe la EverandA Different Perspective: The Traveler's Guide to Medieval (Islamic) Spain and PortugalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 Qur Anic Values and Modernity in Contemporary Islamic EthicsDocument20 pagini6 Qur Anic Values and Modernity in Contemporary Islamic EthicsFahrudin AFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coptic Identity and Ayyubid Politics in Egypt 1218-1250De la EverandCoptic Identity and Ayyubid Politics in Egypt 1218-1250Încă nu există evaluări

- Conversion to Islam in the Premodern Age: A SourcebookDe la EverandConversion to Islam in the Premodern Age: A SourcebookÎncă nu există evaluări

- Defining Boundaries in al-Andalus: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Islamic IberiaDe la EverandDefining Boundaries in al-Andalus: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Islamic IberiaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (1)

- The Proper Order of Things: Language, Power, and Law in Ottoman Administrative DiscoursesDe la EverandThe Proper Order of Things: Language, Power, and Law in Ottoman Administrative DiscoursesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imprisonment in Pre-Classical and Classical Islamic LawDocument18 paginiImprisonment in Pre-Classical and Classical Islamic Lawmcascio5Încă nu există evaluări

- Arabic Authors: A Manual of Arabian History and LiteratureDe la EverandArabic Authors: A Manual of Arabian History and LiteratureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abū Al-Faraj Alī B. Al - Usayn Al-I Fahānī, The Author of The Kitāb Al-AghānīDocument11 paginiAbū Al-Faraj Alī B. Al - Usayn Al-I Fahānī, The Author of The Kitāb Al-AghānīMarlindaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Slandering the Sacred: Blasphemy Law and Religious Affect in Colonial IndiaDe la EverandSlandering the Sacred: Blasphemy Law and Religious Affect in Colonial IndiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Story of Joseph: A Fourteenth-Century Turkish Morality Play by Sheyyad HamzaDe la EverandThe Story of Joseph: A Fourteenth-Century Turkish Morality Play by Sheyyad HamzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- What's Wrong in America?: A Look at Troublesome Issues in Our CountryDe la EverandWhat's Wrong in America?: A Look at Troublesome Issues in Our CountryÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Persian Elite of Ilkhanid IranDocument41 paginiThe Persian Elite of Ilkhanid IranhulegukhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moral Agents and Their Deserts: The Character of Mu'tazilite EthicsDe la EverandMoral Agents and Their Deserts: The Character of Mu'tazilite EthicsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subjectivity in ʿAttār, Persian Sufism, and European MysticismDe la EverandSubjectivity in ʿAttār, Persian Sufism, and European MysticismÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Regency of Tunis, 1535–1666: Genesis of an Ottoman Province in the MaghrebDe la EverandThe Regency of Tunis, 1535–1666: Genesis of an Ottoman Province in the MaghrebÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Confiscated Memory: Wadi Salib and Haifa's Lost HeritageDe la EverandA Confiscated Memory: Wadi Salib and Haifa's Lost HeritageÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sultan S Servants The Transformation of Ottoman Provincial Government 1550 1650Document4 paginiThe Sultan S Servants The Transformation of Ottoman Provincial Government 1550 1650Fatih YucelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dār Al-Islām - Dār Al - Arb. Territories, People, Identities-Brill (2017)Document460 paginiDār Al-Islām - Dār Al - Arb. Territories, People, Identities-Brill (2017)Raas4555Încă nu există evaluări

- The Islamic Obligation To Emigrate Al-Wansharīsī's Asnā Al-Matājir ReconsideredDocument497 paginiThe Islamic Obligation To Emigrate Al-Wansharīsī's Asnā Al-Matājir ReconsideredShaiful BahariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spiritual Subjects: Central Asian Pilgrims and the Ottoman Hajj at the End of EmpireDe la EverandSpiritual Subjects: Central Asian Pilgrims and the Ottoman Hajj at the End of EmpireEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- The Study of Arabic Philosophy in The Twentieth Century - Dimitri GutasDocument21 paginiThe Study of Arabic Philosophy in The Twentieth Century - Dimitri GutasSamir Al-HamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revolutions and Rebellions in Afghanistan: Anthropological PerspectivesDe la EverandRevolutions and Rebellions in Afghanistan: Anthropological PerspectivesM. Nazif ShahraniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islamic Law in Circulation by Mahmood Kooria - Bibis - IrDocument872 paginiIslamic Law in Circulation by Mahmood Kooria - Bibis - IrChris MartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Concept of State in Islam - Feb 15, 06Document51 paginiConcept of State in Islam - Feb 15, 06Ahmad FarooqÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Garden and the Fire: Heaven and Hell in Islamic CultureDe la EverandThe Garden and the Fire: Heaven and Hell in Islamic CultureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crossing Confessional Boundaries: Exemplary Lives in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic TraditionsDe la EverandCrossing Confessional Boundaries: Exemplary Lives in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic TraditionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Origins of the Lebanese National Idea: 1840–1920De la EverandThe Origins of the Lebanese National Idea: 1840–1920Evaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- On the Medieval Structure of Spirituality: Thomas AquinasDe la EverandOn the Medieval Structure of Spirituality: Thomas AquinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arkoun Rethinking Islam Today PDFDocument23 paginiArkoun Rethinking Islam Today PDFnazeerahmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science and Islam-HSci 209-SyllabusDocument10 paginiScience and Islam-HSci 209-SyllabusChristopher TaylorÎncă nu există evaluări

- To Come to the Land: Immigration and Settlement in 16th-Century Eretz-IsraelDe la EverandTo Come to the Land: Immigration and Settlement in 16th-Century Eretz-IsraelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Idolatry and Representation: The Philosophy of Franz Rosenzweig ReconsideredDe la EverandIdolatry and Representation: The Philosophy of Franz Rosenzweig ReconsideredÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advanced French Grammar PDFDocument717 paginiAdvanced French Grammar PDFrocha16048297% (32)

- The Sin of LugalzagesiDocument9 paginiThe Sin of LugalzagesiAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advanced French Grammar PDFDocument717 paginiAdvanced French Grammar PDFrocha16048297% (32)

- Language Shift or Maintenance. The CaseDocument21 paginiLanguage Shift or Maintenance. The CaseAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ahmed Abdul Ghani - Ancient Near Eastern Thought & Literature 2 Anatolian Literature Paper 3Document11 paginiAhmed Abdul Ghani - Ancient Near Eastern Thought & Literature 2 Anatolian Literature Paper 3Ahmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- MQM TerrorismDocument95 paginiMQM TerrorismTerminal X100% (3)

- The Exorcist S Manual Structure Languag PDFDocument42 paginiThe Exorcist S Manual Structure Languag PDFAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- نحو میر اردوDocument137 paginiنحو میر اردوFIQHI MASAIL100% (6)

- Introduction To Akkadian PDFDocument116 paginiIntroduction To Akkadian PDFAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Muhammad Qasim Zaman) Modern Islamic Thought in A (B-Ok - Xyz)Document376 pagini(Muhammad Qasim Zaman) Modern Islamic Thought in A (B-Ok - Xyz)Ahmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bon Voyage: Memphis or Avaris?Document5 paginiBon Voyage: Memphis or Avaris?Ahmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Akkadian Grammar by John HuehnergardDocument700 paginiAkkadian Grammar by John HuehnergardAhmed Abdul Ghani100% (9)

- LANG 127-Persian 1-Athar Masood PDFDocument6 paginiLANG 127-Persian 1-Athar Masood PDFAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- MA Muslim Cultures Application Form 2016 - FINALDocument11 paginiMA Muslim Cultures Application Form 2016 - FINALAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Al Khair Ul Kaseer - by Maulana Muhammad Amin PDFDocument505 paginiAl Khair Ul Kaseer - by Maulana Muhammad Amin PDFAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Badr e Muneer Urdu Shar NahwmeerDocument145 paginiBadr e Muneer Urdu Shar NahwmeerMushtaq55Încă nu există evaluări

- OCR ASA2 Critical Thinking My Revision Notes PDFDocument107 paginiOCR ASA2 Critical Thinking My Revision Notes PDFAhmed Abdul Ghani100% (1)

- LANG 129-Pashto For Non-Pashto Speakers-Bakht MunirDocument5 paginiLANG 129-Pashto For Non-Pashto Speakers-Bakht MunirAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- LANG 128-Sindhi For Non-Sindhi Speakers-Ashok Kumar KhatriDocument5 paginiLANG 128-Sindhi For Non-Sindhi Speakers-Ashok Kumar KhatriAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Grammar of ChagatayDocument222 paginiA Grammar of ChagatayAhmed Abdul Ghani0% (1)

- MaarifulQuran Index ShaykhMuftiMuhammadShafir.ADocument209 paginiMaarifulQuran Index ShaykhMuftiMuhammadShafir.ASaifullah KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mystical Tradition (Starter)Document3 paginiMystical Tradition (Starter)Ahmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mystical Tradition (Description)Document5 paginiMystical Tradition (Description)Ahmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Namaz Timings PDFDocument2 paginiNamaz Timings PDFimranmehfoozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proposal For Improving Students' EnglishDocument4 paginiProposal For Improving Students' EnglishAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doha Meeting Report-LibreDocument36 paginiDoha Meeting Report-LibreAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bashir's Dissertation On Kalasha LanguageDocument464 paginiBashir's Dissertation On Kalasha LanguageAhmed Abdul Ghani100% (1)

- Mirat Ul AroosDocument135 paginiMirat Ul AroosAhmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Taqlid Shakhsi and The Layman Part 1Document3 paginiOn Taqlid Shakhsi and The Layman Part 1Ahmed Abdul GhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Does The Bible Say About AbortionDocument5 paginiWhat Does The Bible Say About AbortionGary Taylor LeesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aligarh MovementDocument3 paginiAligarh MovementSundus RasheedÎncă nu există evaluări

- 100 Years of Thomism - BrezikDocument109 pagini100 Years of Thomism - BrezikjondoescribdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solar EclipcesDocument5 paginiSolar EclipcesGilbert Gabrillo Joyosa100% (1)

- 2ND Sunday of AdventDocument171 pagini2ND Sunday of AdventPeter Paul HernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- THEO 100 (Theology) MidtermsDocument15 paginiTHEO 100 (Theology) MidtermsAlianna RoseeÎncă nu există evaluări

- EngDocument11 paginiEngnadi_nadeemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pius Drijers, The Psalms Their StructureDocument279 paginiPius Drijers, The Psalms Their StructureDavid GraneroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aqeedah - Research Paper - Australian Journal of Humanities and Islamic Studies ResearchDocument13 paginiAqeedah - Research Paper - Australian Journal of Humanities and Islamic Studies ResearchMuhammad NabeelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adelaida de Carillo Holiness Required For HeavenDocument17 paginiAdelaida de Carillo Holiness Required For HeavencrystleagleÎncă nu există evaluări

- To The Young Women of MalolosDocument12 paginiTo The Young Women of MalolosKate Mariel SumadsadÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Atheist Magazine (Spring 2001)Document56 paginiAmerican Atheist Magazine (Spring 2001)American Atheists, Inc.Încă nu există evaluări

- Islamic Religious MusicDocument22 paginiIslamic Religious MusicTiago SousaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Schedules 11Document2 paginiSchedules 11api-25130792Încă nu există evaluări

- Michael P. Murphy - A Theology of Criticism - Balthasar, Postmodernism, and The Catholic Imagination - Oxford University Press, USA (2008)Document225 paginiMichael P. Murphy - A Theology of Criticism - Balthasar, Postmodernism, and The Catholic Imagination - Oxford University Press, USA (2008)Wigbert Papa100% (3)

- Assumption of MaryDocument8 paginiAssumption of MaryConnor Whelan100% (1)

- El Cristo Cósmico, La Superación Del Antropocentrismo PDFDocument15 paginiEl Cristo Cósmico, La Superación Del Antropocentrismo PDFPepe Piedra100% (1)

- Saved But Still EnslavedDocument20 paginiSaved But Still EnslavedChosen Books100% (7)

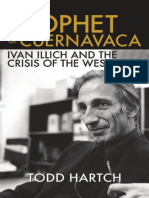

- Prophet of Cuernavaca - Ivan IllichDocument251 paginiProphet of Cuernavaca - Ivan Illichtitiniii100% (2)

- Edo - ReligionDocument260 paginiEdo - ReligionWalter N. RamirezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Merry Christmas MR Bean: See How Many of These Questions You Can Answer After Watching The First SceneDocument4 paginiMerry Christmas MR Bean: See How Many of These Questions You Can Answer After Watching The First SceneNiki HubertÎncă nu există evaluări

- Okja EvalDocument3 paginiOkja EvalJade Bernardine PalerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Evangelism LifestyleDocument91 paginiIntegrated Evangelism LifestyleAGUSTINÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bismullah - Said NursiDocument10 paginiBismullah - Said NursiYakoob Mahomed Perfume HouseÎncă nu există evaluări

- 99 Names of Allah SWTDocument7 pagini99 Names of Allah SWTLiquid_Sky787Încă nu există evaluări

- Rock of Christ - FoundationDocument3 paginiRock of Christ - FoundationSeeker6801Încă nu există evaluări

- Act of Contritions - English & SpanishDocument2 paginiAct of Contritions - English & SpanishGon FloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 4Document22 paginiUnit 4gcorreabÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marriage (Kitab Al-Nikah) From Sunan Abu-Dawud Translated by ProfDocument2 paginiMarriage (Kitab Al-Nikah) From Sunan Abu-Dawud Translated by Profghazi4uÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ibn Taymiyyah On The Existence of EvilDocument34 paginiIbn Taymiyyah On The Existence of EvilNomaan MalickÎncă nu există evaluări