Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Richard Rogers

Încărcat de

Bozana PetrovicTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Richard Rogers

Încărcat de

Bozana PetrovicDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Richard Rogers: Observations on Architecture

Though a building must be complete at any one stage, it is our belief that in order to allow for growth and change it should be functionally and therefore visually open-ended. This indeterminate form must offer legible architectural clues for the interpretation of future users. The dichotomy between the complete and the open nature of the building is a determinant of the aesthetic language. We design each building so that it can be broken down into elements and subelements which are then hierarchically organised so as to give a clearly legible order. A vocabulary is thereby created in which each element expresses its process of manufacture, storage, erection and demountability; so that, to quote Louis Kahn, each part clearly and joyfully proclaims its role in the totality. "Let me tell you the part I am playing, how I am made and what each part does", what the building is for, what the role of the building is in the street, and the city.' ... I believe in the rich potential of modem industrialist society. Aesthetically one can do what one likes with technology for it is a tool, not an end in itself, but we ignore it at our peril. To our practice its natural functionalism has an intrinsic beauty. The aesthetic relationship between science and art has been poetically described by Horatio Greenough as: 'Beauty is the promise of function made sensuously pleasing.' It is science to the aid of the imagination... We are searching for a system and a balance which offers the potential for change and urban control; a system in which the totality has complete integrity yet allows for both planned and unplanned change. A dynamic relationship is then established between transformation and permanence, resulting in a three-dimensional framework with a kit of changeable parts designed to allow people to perform freely inside and out. This free and changing performance of people and parts becomes the expression of the architecture... (pp 12-13) The architect must understand and control the machinery - the instruments that build buildings where necessary developing and inventing new ones... Only by studying and controlling the means of production and by creating a precise technological language will the architect keep control of the design and construction of the building. The correct use of building process disciplines the building form, giving it scale and grain... Today problem solving involves thinking at a global scale and using science as the tool to open up the future. Science is the means by which knowledge is ordered in the most efficient way so as to solve problems... (p16) The building form, plan, section and elevation should be capable of responding to changing needs. This free and changing performance will then become part of the expression of the architecture of the building, the street and the city. Program, ideology and form will then play an integrated and legible role within a changing but ordered framework. The fewer the building constraints for the users, the greater the success; the greater the success the more the need for

revision and then programmatic indeterminance will become an expression of the architecture... (p 19)

Jean-Louis Cohen: Composition according to Rogers

Richard Rogers's first residential projects possessed great conceptual clarity. He alluded to Mies van der Rohe with his House in Wimbledon (1968-9) and evoked the settlements then being imagined for distant planets with his project for the Zip-up House (1969-71). Imbuing his designs with a sense of modular composition no matter the scale, he continued to leave all the pipes exposed on the exterior as at the Centre Pompidou. (The British television program Spitting Image satirized him with a puppet whose intestines were hanging out.) This approach led him to build hangars with cable-stiffened structures such as those for the Fleetguard Factory in Quimper, France (1979-81), the INMOS Microprocessor Factory in Gwent, Wales (1982-7), and the PA Technology Center in Princeton, New Jersey (1982-5). All displayed a certain classicism by virtue of their symmetry, the similarity between their front and back elevations, and the rigorous treatment of their corners. The Lloyd's Building (1978-86) 556 in the City of London marked a significant change of scale in Rogers's work. This large structure was conceived by Rogers as an open space with floors branching out from a central atrium. At its heart is the insurance company's famous Lutine Bell, surrounded by the servant spaces of the circulation cores and utilities. The building recalls nineteenth-century department stores and, even more literally, Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace, especially with its semicircular tympanums. From this building on, Rogers has worked mostly on large public buildings, abandoning any residual classicism in favor of more expressive solutions, as in the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg (1989-95) and his ourthouse in Bordeaux (1993-6), whose chambers are located in rooms evoking oversized wine vats. Rogers designed the gigantic Millennium Dome in Greenwich, England (1995-9), a fabric membrane suspended from a network of steel cables and masts, which long failed to find a use commensurate with its structural ambitions. Richard Rogers's general method is first to work out his projects in section, next to define a basic modular unit to be repeated according to a grid or linear sequence, and then to generate the complete building, as exemplified in his terminal at Barajas Airport in Madrid (1997-2005) 555 with its wave-shaped roof.

Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers: Statement

Ideology cannot be divided from architecture. Change will clearly come from radical changes in social and political structures. In the face of such immediate crises as starvation, rising population, homelessness, pollution, misuse of non-renewable resources and industrial and agricultural production, we simply anaesthetise our consciences. With problems so numerous and so profound, with no control except by starvation, disease and war, we respond with detachment. Today, at best, we can hope to diminish the coming catastrophe by the recognition of the existing human conditions and by rational research and practice. The importance of technology is in the application of method to technique, whether one is talking of sophisticated or primitive technology. The aim of technology is to satisfy the needs of all levels of society. Technology cannot be an end in itself but must aim at solving long term social and ecological problems. This is impossible in a world where short term profit for the

'haves' is seen as a goal, at the expense of developing more efficient technology for the 'have nots'. All forms of technology from low energy intensive to high energy intensive must aim at conserving natural resources while minimising ecological, social and visual damage to the environment, so that by using as little material as possible as functionally as possible to answer new briefs, we reach a self-sustaining situation where input = output. A new distribution of end and means is needed, not based purely on a limited financial evaluation of human needs. In this context it is as difficult to create a truly socially orientated brief as it is to adapt and translate it by the use of the correct technological means ... Much of our work has the following common factors: a. Analysing and broadening the brief to create an environment which will offer maximum freedom for man's many different activities. Reassessing traditional hierarchies and relationships between public and private, work and relaxation, child and adult, vehicular and pedestrian, worker and manager, quiet and noisy, dangerous and safe. Each overlapping realm requires special conditions to sustain and encourage it. b. Single undefined common spaces. c. Allowance for growth and change. d. No major differentiation in the section and facade except in the direction of growth as in clear span structure. e. Control of programme, quality and cost by the use of standard catalogue pieces and the elimination of craft techniques and wet trades ... f. Maximum exploitation of minimum industrial materials. g. Use of skilled erection teams. h. Building forms and dimensions dictated by maximum economic spans and standard production limits of components. High thermal insulation and general environmental control by the use of sophisticated panel systems... j. Skin, structure and services clearly defined. k. Internal and external elements demountable and reusable. Use of bright colors to give order, happiness and to break down technological connotations. m. Breakdown of traditionally hierarchical planning, replaced by work flow planning. Piano and Rogers, Statement from Architectural Design, vol XLV; no 5, 1975.

Jean-Louis Cohen: Experimentation according to Piano

Renzo Piano followed a rather different path, taking less interest in composition per se than in devising distinctive details characteristic of each project. His work started with the polyester panels and steel braces of his Italy Pavilion at the Osaka World's Fair (1970). Then, at the Centre Pompidou, he developed the "gerberette" - a cantilevered arm connecting the steel columns to the floor-carrying trusses and wind bracing which condensed the spatial and technical solution into a single component. His simplest museum to date, and one of his most successful, is the Menil

Collection in Houston (1982-6), a one-story box with opaque elevations, top-lit by a network of three hundred adjustable "leaves" in glass-reinforced concrete that serve to temper the bright Texas light. The experimental research of Piano's architectural firm - RPBW, or Renzo Piano Building Workshop - has been carried out with full-scale models, leading to several different families of buildings and to structural solutions that have usually been defined by a guiding metaphor. The Kansai International Airport on an artificial island in Osaka Bay (1988-94) 557 resembles a wave extending along the runways for just over a mile, although it may also be compared to the wing of a glider, beneath which the terminal's operations are carried out. In the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center in Noumea, New Caledonia (1991 - 8), arches of laminated wood reinterpret native Kanak huts, and they also give the complex the appearance of a group of masks, especially when viewed straight-on from the water. The same laminated wood concept was used for the tall arches of the Bercy II Shopping Center in Paris (1987- 90), over which a metal skin is stretched, resulting in a structure whose interior resembles that of the whale in Walt Disney's Pinocchio. Piano has approached the question of cladding from several different angles. For his residential complex on Rue de Meaux in Paris (1988-91), he used prefabricated "leaves" in fiberglassreinforced concrete to which a terra-cotta facing was clipped. He further developed this system for his first skyscraper, the DEBIS tower on Berlin's Potsdamer Platz (1992-9). In Berlin as well as in subsequent skyscrapers, like Aurora Place in Sydney (1996- 2000) and the New York Times Building in Manhattan (2000-8), Piano extended the principle of servant and served spaces vertically, at the same time giving a genuine tectonic complexity to the building skins. With his conversions of industrial sites such as the Schlumberger Factory in Montrouge (1981-4) and the Lingotto Factory in Turin (1983- 2002), Piano endeavored to clarify the process of transformation by preserving the original buildings' spatial and structural qualities. This attention to the relationship between building components has also been characteristic of his many projects for cultural institutions in Europe and, increasingly, the United States, where he developed a reputation as deus ex machina, able to solve the most complicated problems. The Beyeler Foundation Museum in Riehen, near Basel (1992-7), in which opaque walls divide up a space underneath a floating roof, further elaborates the theme of the Menil Collection. The small Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, with its five parallel bays, derives from the same approach. In the Parco della Musica Auditorium in Rome (1994-2002), the walls enveloping the lobbies and auditoriums express a sort of "wallness" that seems inspired by antiquity, while the lead-coated wood shells sheltering the three music spaces are in an Expressionist vein, reminiscent of Hermann Finsterlin's mysterious animal-like fantasies.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Research DesignDocument21 paginiResearch DesignAbigael Recio Sollorano100% (1)

- Las Casas Filipinas de Acuzar: Heritage Conservation or Historical AlterationDocument5 paginiLas Casas Filipinas de Acuzar: Heritage Conservation or Historical AlterationRen MaglayoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cluster Housing and Planned Unit Development PudDocument71 paginiCluster Housing and Planned Unit Development PudRoi KimssiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study Reimagining The Street by Adapting Various Planning Concept.Document5 paginiCase Study Reimagining The Street by Adapting Various Planning Concept.Aja MoriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tad2 - Design and Public PolicyDocument6 paginiTad2 - Design and Public PolicyJay ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- SOCIO-CULTURAL BASIS OF COMMUNITY DESIGNDocument7 paginiSOCIO-CULTURAL BASIS OF COMMUNITY DESIGNAileen Joy0% (1)

- Site Planning 1Document52 paginiSite Planning 1Emil John Baticula100% (1)

- Background Sample KineticDocument2 paginiBackground Sample KineticMart Peeters CaledaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Construction of Pervious PavementDocument37 paginiConstruction of Pervious PavementJessa Dynn Agraviador VelardeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ad428 Gumallaoi Judelle v. Ar Programming 4aDocument55 paginiAd428 Gumallaoi Judelle v. Ar Programming 4aLuwella GumallaoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parastoo Rajaei, Part 1,2 and 3 + AppendicsDocument84 paginiParastoo Rajaei, Part 1,2 and 3 + AppendicsParastOo Ra Ja EiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bu3 Final Case StudyDocument43 paginiBu3 Final Case StudyFaye DomingoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 3 PPT SPP 203 Part 2 of 2Document19 paginiWeek 3 PPT SPP 203 Part 2 of 2Lindsey BalangueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Glossary of Urban Planning Terms Flashcards - QuizletDocument60 paginiGlossary of Urban Planning Terms Flashcards - QuizletEma AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1-3Document53 paginiChapter 1-3Joven Loyd IngenieroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prof Prac 2Document2 paginiProf Prac 2easy killÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Practice of Architecture in The PhilippinesDocument3 paginiThe Practice of Architecture in The PhilippinesJust scribble me For funÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil Code For RLAsDocument40 paginiCivil Code For RLAsOwns DialaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Development ControlsDocument26 paginiDevelopment ControlsGabbi GÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architect's CredoDocument1 paginăArchitect's CredoDenmarynneDomingoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Professional Practice 2 Reviewer: Standards and Selection MethodsDocument1 paginăProfessional Practice 2 Reviewer: Standards and Selection MethodsPatricia de los SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- RSW#1 - Ekistics - Ferrer, Zildjian M.Document23 paginiRSW#1 - Ekistics - Ferrer, Zildjian M.Zj FerrerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bale Kultura: An Incorporation of Filipino Neo Vernacular Architecture On A World Class Multi-Use Convention CenterDocument9 paginiBale Kultura: An Incorporation of Filipino Neo Vernacular Architecture On A World Class Multi-Use Convention CenterMary Alexien GamuacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architectural Design 7-ESQUISSE NO. 1Document4 paginiArchitectural Design 7-ESQUISSE NO. 1carlo melgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arc 150 Sas 7 Comprehensive Approach To HousingDocument18 paginiArc 150 Sas 7 Comprehensive Approach To HousingJhonkeneth ResolmeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Malcolm-Square With Other InputsDocument6 paginiMalcolm-Square With Other InputsDanah Angelica SambranaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Professional Practice Answer SheetDocument10 paginiProfessional Practice Answer SheetRalph Juneal BlancaflorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standard of Professional Practice (SPP) On Specialized Architectural ServicesDocument32 paginiStandard of Professional Practice (SPP) On Specialized Architectural ServicesAudrina Seige Ainsley ImperialÎncă nu există evaluări

- Convention and Recreation: Issues To Consider Description Architectural RejoinderDocument2 paginiConvention and Recreation: Issues To Consider Description Architectural RejoinderAaron Patrick Llevado RellonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rediscovering history through foodDocument4 paginiRediscovering history through foodNina ArtÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Importance of The 5-External Environment in The Professional Practice of Architecture.Document2 paginiThe Importance of The 5-External Environment in The Professional Practice of Architecture.lester aceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Real Life Cases: OutlinesDocument6 paginiReal Life Cases: OutlinesJayson BauyonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contract FayofayDocument6 paginiContract Fayofaymfm saventphilsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matrix DiagramDocument1 paginăMatrix DiagramDoroty CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- BP 344 - Provisions Related To NBCDocument16 paginiBP 344 - Provisions Related To NBCElison BaniquedÎncă nu există evaluări

- SpaceDocument6 paginiSpaceSilao, IdyanessaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Top 10 Tallest Building in The Philippines: A Comparative AnalysisDocument10 paginiTop 10 Tallest Building in The Philippines: A Comparative AnalysisTrisha LlamesÎncă nu există evaluări

- ENGAGE COMMUNITIES IN ARCHITECTUREDocument5 paginiENGAGE COMMUNITIES IN ARCHITECTUREjodieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavioral and Cultural Influences on Filipino Housing DesignDocument22 paginiBehavioral and Cultural Influences on Filipino Housing DesignAaron Steven PaduaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project No. 1: A Proposed 2-Storey Residential Project, R-1 With 2% SlopeDocument5 paginiProject No. 1: A Proposed 2-Storey Residential Project, R-1 With 2% Slopeaprelle soriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study: St. JosephvilleDocument21 paginiCase Study: St. JosephvilleRio Sumague100% (1)

- Planning 1:: Site Planning and Landscape ArchitectureDocument8 paginiPlanning 1:: Site Planning and Landscape ArchitectureMJ TualaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rules and Regulations For Urban Design and PlanningDocument5 paginiRules and Regulations For Urban Design and PlanninghulpeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Encouraging Passive Cooling and Atrium Architecture in Philippines BuildingsDocument10 paginiEncouraging Passive Cooling and Atrium Architecture in Philippines BuildingsJohnBenedictRazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design Research FinalDocument55 paginiDesign Research FinalChristelle AbusoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Concert Hall AcousticsDocument2 paginiPhilippine Concert Hall AcousticsgreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balangay-inspired tropical home designDocument4 paginiBalangay-inspired tropical home designKhim Jane BuyserÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alpas Community-Based Rehabilitation Center for PWDsDocument2 paginiAlpas Community-Based Rehabilitation Center for PWDsAngelo TabbayÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Redevelopment of Binirayan Sports Complex: Developing Adaptive Recreational Facilities For Sustainable Architecture" San Jose de Buenavista, AntiqueDocument12 pagini"Redevelopment of Binirayan Sports Complex: Developing Adaptive Recreational Facilities For Sustainable Architecture" San Jose de Buenavista, AntiqueJohn Remmel Roga100% (1)

- Transformative ArchitectureDocument3 paginiTransformative Architecturesammykinss100% (1)

- Uap HistoryDocument3 paginiUap HistoryjaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Problems Challenging Architectural Education in The Philippines: Exploring New Teaching Strategies and MethodologyDocument9 paginiProblems Challenging Architectural Education in The Philippines: Exploring New Teaching Strategies and MethodologyArki AlphaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Berde Rating SystemDocument8 paginiBerde Rating SystemKaye Reyes-HapinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architectural Design 9 - Thesis Research Writing: Palutang Location: Bacoor BayDocument6 paginiArchitectural Design 9 - Thesis Research Writing: Palutang Location: Bacoor BayJD LupigÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architecture Vernacular TermsDocument3 paginiArchitecture Vernacular TermsJustine Marie RoperoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aesthetic and Physical Considerations in Site PlanningDocument2 paginiAesthetic and Physical Considerations in Site PlanningJeon JungkookÎncă nu există evaluări

- SPP DocsDocument11 paginiSPP DocsJansen AriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- BU Elec Lighting Notes Pugeda 2Document2 paginiBU Elec Lighting Notes Pugeda 2Zianne CalubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Project 1Document234 paginiThesis Project 1Alberto NolascoÎncă nu există evaluări

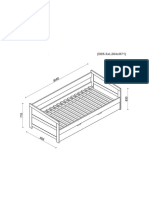

- Version1 Bed LolaDocument1 paginăVersion1 Bed LolaBozana PetrovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architectural StructuresDocument227 paginiArchitectural StructuresMohamed Zakaria92% (24)

- Mass Customization at BMWDocument17 paginiMass Customization at BMWsunnyccccc100% (1)

- Non-Uniform Assemblage - Mass Customization in Digital FabricationDocument9 paginiNon-Uniform Assemblage - Mass Customization in Digital FabricationBozana PetrovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Produced by An Autodesk Educational ProductDocument1 paginăProduced by An Autodesk Educational ProductBozana PetrovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Archdesign PDFDocument219 paginiArchdesign PDFAdina CampianÎncă nu există evaluări

- StvariDocument1 paginăStvariBozana PetrovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raspored Sav PDFDocument1 paginăRaspored Sav PDFBozana PetrovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Richard RogersDocument4 paginiRichard RogersBozana PetrovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Second Comming AnswersDocument5 paginiThe Second Comming AnswersBozana PetrovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- RC Design IIDocument58 paginiRC Design IIvenkatesh19701Încă nu există evaluări

- 2206 - Stamina Monograph - 0 PDFDocument3 pagini2206 - Stamina Monograph - 0 PDFMhuez Iz Brave'sÎncă nu există evaluări

- CSSBI Tablas de Carga Perfiles PDFDocument60 paginiCSSBI Tablas de Carga Perfiles PDFRamón RocaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Return SectionDocument1 paginăReturn SectionDaniel Pouso DiosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smart Asthma ConsoleDocument35 paginiSmart Asthma ConsoleMohamad Mosallam AyoubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Projects in the Autonomous Region in Muslim MindanaoDocument4 paginiProjects in the Autonomous Region in Muslim MindanaoMark montebonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analytical Chemistry Lecture Exercise 2 Mole-Mole Mass-Mass: Sorsogon State CollegeDocument2 paginiAnalytical Chemistry Lecture Exercise 2 Mole-Mole Mass-Mass: Sorsogon State CollegeJhon dave SurbanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elimination - Nursing Test QuestionsDocument68 paginiElimination - Nursing Test QuestionsRNStudent1100% (1)

- Electronics Meet Animal BrainsDocument44 paginiElectronics Meet Animal BrainssherrysherryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spectrophotometric Determination of Triclosan Based On Diazotization Reaction: Response Surface Optimization Using Box - Behnken DesignDocument1 paginăSpectrophotometric Determination of Triclosan Based On Diazotization Reaction: Response Surface Optimization Using Box - Behnken DesignFitra NugrahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class-III English Notes-WsDocument6 paginiClass-III English Notes-WsManu SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metaphors As Ammunition The Case of QueeDocument19 paginiMetaphors As Ammunition The Case of QueeMarijana DragašÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discrete Variable Probability Distribution FunctionsDocument47 paginiDiscrete Variable Probability Distribution FunctionsJanine CayabyabÎncă nu există evaluări

- Volvo g900 Modelos PDFDocument952 paginiVolvo g900 Modelos PDFAdrianDumescu100% (3)

- Tyco TY8281 TFP680 - 03 - 2023Document17 paginiTyco TY8281 TFP680 - 03 - 2023First LAstÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iso 1924 2 2008Document11 paginiIso 1924 2 2008Pawan Kumar SahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2021 Vallourec Universal Registration DocumentDocument368 pagini2021 Vallourec Universal Registration DocumentRolando Jara YoungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sing 2Document64 paginiSing 2WindsurfingFinnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pancreatic NekrosisDocument8 paginiPancreatic Nekrosisrisyda_mkhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Din en 1320-1996Document18 paginiDin en 1320-1996edcam13Încă nu există evaluări

- Scheme of Valuation and Key for Transportation Engineering ExamDocument3 paginiScheme of Valuation and Key for Transportation Engineering ExamSivakumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- GCSE 1MA1 - Algebraic Proof Mark SchemeDocument13 paginiGCSE 1MA1 - Algebraic Proof Mark SchemeArchit GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Starter Unit Basic Vocabulary: Smart Planet 3Document21 paginiStarter Unit Basic Vocabulary: Smart Planet 3Rober SanzÎncă nu există evaluări

- JKF8 Intelligent Reactive Power Compensation ControllerDocument4 paginiJKF8 Intelligent Reactive Power Compensation ControllerGuillermo Morales HerreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- M2030 PA300 Siren Data Sheet 5-2021Document2 paginiM2030 PA300 Siren Data Sheet 5-2021parak014Încă nu există evaluări

- Traffic Sign Detection and Recognition Using Image ProcessingDocument7 paginiTraffic Sign Detection and Recognition Using Image ProcessingIJRASETPublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Making Soap From WoodDocument6 paginiMaking Soap From WoodmastabloidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prob Stats Module 4 2Document80 paginiProb Stats Module 4 2AMRIT RANJANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Traxonecue Catalogue 2011 Revise 2 Low Res Eng (4!5!2011)Document62 paginiTraxonecue Catalogue 2011 Revise 2 Low Res Eng (4!5!2011)Wilson ChimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lea 2 PDFDocument21 paginiLea 2 PDFKY Renz100% (1)