Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cargo Work Full Notes PDF

Încărcat de

tejmayerDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cargo Work Full Notes PDF

Încărcat de

tejmayerDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

MODULE 1 -TYPES OF CARGO

Brief description on types of cargoes carried onboard merchant ships are as follows: -

Coal

*oal is a minerali+ed fossil fuel widely utilised as a source of domestic and industrial power. ,s a sea borne product, it is always carried in bulk. It varies from soft bituminous type to hard anthracite through to manufactured coal products. -espite the carriage of coal being an established trade, it remains as a difficult and dangerous cargo to transport due to dangers of gas e plosion, spontaneous combustion, and cargo shifting during passage and corrosion to ships hold.

General Cargo

The modern term for these types of cargoes is breakbulk cargoes. It consists of individual items, e.g. pieces of machinery, bags, bales, and small quantities of liquids e.g. late in deep tanks etc. !eavy items may be lifted onboard using ships gear or shore cranes.

Grain

"rain comprises of wheat, corn, rye, barley, oats, rice etc. "rains are liable to heat and#or sweat, especially if damp, when they may germinate or rot, therefore requiring careful pre-loading inspection, carriage and ventilation. In ma$or grain ports, handling equipment%s are sophisticated, grain elevators being equipped to unload railway wagons, lorries, barges or coastal craft and to reload from storage silos at high speed into ocean going ships. &or discharging grains, the pneumatic sucker system, evacuators and grabs may be utilised.

Fertiliser

.ay be carried in bulk, bags or liquid forms. .ost fertili+ers are harmless, especially in bags but a few can be e plosive and#or corrosive. The I./ -angerous goods *ode should be consulted when carrying these cargoes.

Cement

It may be subdivided mainly into bagged or bulk cargo in either finished cement or clinkers. It should be kept scrupulously dry so as to avoid solidifying. It is often preferred to load bagged cement into the tweendecks of general cargo ships having the facility of reducing the height of stow which in the case of e cessive tier heights in single deck ships may cause splitting of lower stowed bags. The handling of clinker is not so critical as it is normally carried in bulk0 it can however be e tremely dusty and is therefore sub$ected to shore-based anti pollution regulations.

Timber

Includes timber and its by product - e.g. hardwood and softwood logs, sawn timber, wooden products, wood chips wood pulp and paper products. 'here practicable, timber as it is, is carried on deck. The securing and proper stowage of deck timber has the effect of increasing a ships freeboard and because of this timber carrier may be allotted lumber loadlines in addition to the usual load lines. Timber loadlines allow ships to load more cargo as compared to the ordinary load lines as it has the following effects: a. (eserve buoyancy of vessel is increased by compact mass of buoyant timber above the freeboard deck. b. )ffective freeboard is increased with beneficial effect on the range stability. c. 'eather deck hatches are protected.

Livesto !

1ormally carried on the weatherdeck in tiers of specially constructed pens. Includes sheep, goats, cattle and buffaloes. /n this type of trade it is not unusual for ships to carry up to 233,333 animals and thus the provision of adequate of fodder and drinking water is a ma$or problem.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 1

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

Metals

These covers the whole range from raw base materials to metal articles e.g. steel products to scrap metal. ,ll steel products are liable to shift at sea and need careful stowage, not only to prevent any movement, but also to avoid seriously damaging the ship. (ust will seriously affect the value of steel products and every effort should thus be made to avoid its occurrence.

Li$%i"s

7ea borne liquids range from drums of products such as bitumen capable of carriage in conventional tween deck ships, to parcels of edible oils transported in specially coated and heated tanks and to huge homogenous cargo of crude mineral oil carried by 89**%s. .ost of these products are inflammable with a low flash point and many are dangerous in other ways, either emitting to ic gases or possessing corrosive qualities or both.

Unitise" Cargo

,ny two or more cargo $oined together is said to be unitised - strapping together, preslinging, palletisation, containeri+ation, etc. ,lthough unitisation may increase costs to some e tent 4e tra packaging cost5, it enhances cargo handling operations, reduce pilferages simplify tallying, reduce the number of people per gang. In another words it contributes greatly to a faster turn around time for the ship. ) ample of unitised cargo is of soft drinks packed on pallet.

Gases

*onsists mainly of liquefied petroleum gas 9:" and liquefied natural gas - 91". 9:" consists mainly of propane and butane and are carried either under pressure at ambient temperature, fully refrigerated 4-;3 to <=*5 or semi refrigerated under a combination of pressure and reduced temperature. ,ny gas that vaporises during handling and carriage will be reliquefied and circulated back to the tanks. 91" is mainly ethane with propane and butane making up the balance. It is carried at or near its boiling point temperature of - 2><* at atmospheric pressure. /ne of the particular features of 91" is that cargo boil off is used as fuel by the ship. !owever, given the high value of natural gas, the use of boil off for such purpose is becoming uneconomic and efforts are being made to reduce the daily rate of boil off to below 3.?@A of cargo quantity.

Containers

*ontainers are basically $ust a bo in which cargoes are placed and the bo itself is transported. .a$ority of general purpose containers are bo es constructed with walls of aluminium or thin steel sheeting, corrugated to provide strength and rigidity, reinforced corner posts with double watertight doors at one end. 6sed to carry various types of cargo e.g. tobacco, electronic components, clothing etc.

Dangero%s Cargo

6nder the auspices of I./, a -angerous "oods *ode has evolved encompassing recommendations as to stowage, carriage, packaging, documentation and labeling of most dangerous commodities. Bulk carriers are likely to be affected by the carriage by one homogenous dangerous cargo at a time e.g. sulphur in bulk or a chemical tanker is likely to carry several lots of dangerous bulk liquids at any one time. !owever, it is the general cargo ships container ships, which can be e pected carry several classes of dangerous goods any one time, the relative effect of which or to at in

Ree#er

These are mainly concerned with the carriage of fruits and vegetables and are seasonal, relying on the harvesting of crops around the world. /ther reefer cargoes include fro+en fruit $uices, flowers and bulbs, dairy products, meat, poultry and fish, pharmaceuticals, -ray films etc. They are handled either as a break bulk, in pallets or in containers. They require scrupulously clean and odorless cargo compartments to avoid contamination and the carriage temperature is absolutely critical.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 2

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

relation to stowage and reaction between cargoes can be somewhat complicated. IMDG code covers carriage of dangerous goods in packaged from or in solid form in bulk. The I.-" code comes in < volumes plus a supplement. ,nother publication dealing with carriage of dangerous goods in 6B is known as CBlue BookD. NOTE - -etail description of specific cargoes will be given in the subsequent modules where appropriate.

advantage, with due regard to the necessary care and attention to conditions of stowage. Thus, the freight earning capability of the vessel is kept at a ma imum. To do this it is necessary to know the amount of space, which each tonne of a commodity will occupy. 7T/',") &,*T/( is defined as the volume in cubic meters a tonne of that cargo will occupy. The figure does not e press the actual measurement of a tonne of the cargo but takes into consideration the necessary for dunnage and the form and design of the packages. ) amples of stowage factors are: *oal 2.2=#2.;; cu.m.#tonne. .ai+e 2.;E cu.m.#tonne. (ubber in bales. 2.=2#2.=E cu.m.#tonne ,n intelligent knowledge of the use of stowage factors is necessary to all cargo officers in order that they may make economic use of each available space unit.

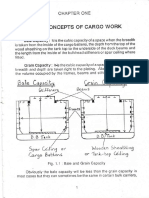

&ale Ca'a it(

This is the cubic capacity of a cargo compartment when the breadth is taken from the inside of the cargo battens or from the inner edges of the frames, and the height from the tank top to the lower edge of the beams and the length from inside of the bulkhead stiffeners or sparring where fitted.

Grain Ca'a it(

This is the total internal volume of a cargo compartment measured from shell plating to shell plating and from tank top to under deck and an allowance is given for the volume occupied by frames and beams. This space is not only associated with the carriage of grain, as such, but with any form of bulk cargo, which would stow similarly, that is to say completely filling the space. It is obvious that a solid cargo can be stowed only up to the limits of the frames and beams whereas bulk cargo will flow around such members. Therefore when measuring for general cargo, it is the bale capacity, which is taken into consideration. ,lthough both grain and bale capacities are normally used to show the volume or capacity of a ship to carry cargo, other units of measurement are more appropriate for specific trades, e.g. T)6s for container ships, lane-metres for (o-(o ships, etc.

&ro!en Sto)age

This is defined as that space in a loaded cargo compartment that is not filled with cargo. It is the space occupied by dunnage, the space between packages and the space that is left over the last tier placed in stowage. Broken stowage is e pressed as a percentage of the total space of the compartment. The percentage that has to be allowed varies with the type of cargo and with the space of the compartment. It is greatest when large cases have to be stowed in an end hold due to the shape of the compartment. Broken stowage in an end hold due to the shape of the compartment. Broken stowage on uniform packaged commodities will average about 23A that on general cargo will average about ?@A. &or e ample: a5 , consignment of apples packed in bo es having stowage factor 2.;2cu. m#ton to be loaded in a cargo space having bale capacity equals to 2333cu m. *alculate the total amount in weight that can be loaded. "iven cargo hold space F 2333 cu m cargo stowage factor F 2.;2

Sto)age Fa tor

&or successful loading, a vessel must utili+e every cubic meter of space to the best

ALAM/July 2002

Page 3

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

cargo loaded

F stowage factor 2333 F 2.;2 F E>;.;> Tons #

volume

b5 6sing the above question 425 *alculate the total amount of cargo to be loaded if 23A broken stowage is allowed. 1ett volume occupied by cargo allowing for 23A broken stowage 2333 cu m F 2.2 F G3G.3G cu m G3G .3G cu m cargo loaded F 2.;2 cu m#ton F >G;.G> Tons

is carefully drawn up to show the identification, description and quantity of the goods 4as verified from the ship%s tally sheets5. ,ny damage to the cargo noticed before loading on board is entered on the .#( and the receipt is then said to be Hclaused%. ,ll particulars from the .#( are transferred to the HBill of 9ading%.

) Bill of Lading (B/L) - is properly prepared by the ship-owner 4or his agent5 from details in the .ate%s (eceipt, and delivered to the shipper - freight being usually paid at this stage. It is a legal document, which provides evidence of a Hcontract of carriage% between the shipper and the ship owner 4the carrier5. It also acts as a document of title to the goods described therein i.e. the holder of the B#9 is regarded as the rightful owner of the cargo. c) Ca go Manifest - is a document containing

a detailed and complete list of cargo Has loaded%, compiled by the ship owner 4or his agent5 from the Bill of 9ading. *opies of the manifest are delivered to the ship, the stevedores at the discharging ports and to *ustoms authorities at the discharging ports. ,s it is a comprehensive record of all cargo in the vessel, it permits the checking of cargo during discharge thereby avoiding overcarriage#short landing. "overnment ,uthorities may use it as material for compilation of the national trade statistics vi+. the nation%s imports#e ports.

Dea")eig*t Cargo

Is cargo on which freight is usually charged on its weight. *argoes which measures 2.??cu.m.#tonne 4s.f5 or less is classed as deadweight cargo.

Meas%rement Cargo

Is cargo on which freight is usually charged on the volume occupied by the cargo and this cargo is usually light, bulky cargo having a stowage factor of more than 2.?? cu.m.#tonne. It has been the custom to set two standards by which cargo is measured and freight is charged. This is in order to avoid e cessive freight charges, which might be out of proportion to the space occupied by a particular consignment, and to protect the ship from loss of freight commensurate with the amount of space used.

d) Ca go !lan - is a plan drawn up by the

ship%s cargo officer showing the stowage of all cargo on board the vessel. *opies of the plan are sent in advance to the discharge ports so that preparations for her unloading can be made before arrival at the port. ,long with the summary of the cargo on board, a well drawn up cargo plan greatly assists in facilitating discharge and avoidance of overcarraige#short landing of cargo.

A" +alorem Cargo

&reight for certain e pensive cargoes, e.g. precious stones, fold bars, etc. is not levied based on weight or measurement but on the value of the cargo.

e) Dange o"s Ca go List - a shipper is

obligated to declare to the .aster full details of any dangerous#ha+ardous cargo shipped by him and covered under the CInternational .aritime -angerous "oods *ode% 4the I...-.". *ode5. The .aster is required to prepare a list of all dangerous#ha+ardous cargo

Page !

Cargo Do %mentations

a) Mates Receipt (M/R) - is a document of

receipt given by the ship%s chief officer 4the .ate5 for goods actually received on board. It

ALAM/July 2002

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

shipped on board. It should show the correct technical name of the commodity, its Hclass% as per the I...-.". *ode, its quantity and weight, position of stowage on board, port of loading and the port of discharge.

Hbacklash% does not occur when the bilge pump is stopped. ?.; *hecking the hold fire detection # e tinguishing systems - most ships are fitted with the */? e tinguishing system and the */? lines to the hold are cleared by passing compressed air. 6sing artificial smoke usually checks the detection system. ?.< *hecking oil#water tightness of the -ouble Bottom tank top and its manhole covers - this is done by pressing up the tank to a head of oil#water and checking for leaks. ;.3 Ma)ing t#e $old *e %in f ee 8ermin such as rats, cockroaches, silver fish etc, in the holds, can cause e tensive damage to cargo on board resulting in huge damage claims from shippers#consignees. It is a requirement by law that every ship must be in possession of a valid -erating *ertificate. The :ort .edical /fficer issues this certificate after fumigation by the burning of sulphur or the release of cyanide gas has been carried out. The certificate is valid for si months, after which a -erating ) emption certificate will be issued if no diseased rats or a large number of rats are found on board. The rat population may be kept to a minimum by the use of anticoagulant bait, such as sodium fluoracetate. *ockroach bait, pesticides and insecticides may be used to e terminate cockroaches and other insects. *leanliness is the most important factor in keeping a ship vermin free. 'hen certain cargoes such as rice, are loaded, the holds are fumigated after loading to rid the cargo of weevils.

Pre'aration O# ,ol" Prior To Loa"ing General Cargo

,s temporary custodians of the cargo, it is the duty of the ship%s officers to ensure that cargo is delivered in the same condition as it was received on board. Besides ensuring that damage to cargo does not occur during handling 4slinging, lifting by derricks#cranes, working forklifts etc5, it is also important to prevent damage as a result of the condition of the hold itself. 2.3 Cleaning t#e $old 1"1 The method and amount of cleaning required will depend upon the type of cargo previously carried in the hold. "enerally speaking, a hold which is ready to receive cargo should be swept clean, dry, well ventilated and free from odour of the previous cargo4es5.

1"2 The hold should be cleaned prior to

loading. The degree of cleanliness required will depend on the nature of the cargo to be loaded. *argoes such as grain, sugar etc. will need a scrupulously clean hold 4and usually surveyed5 before loading can commence, whilst cargoes such as coal, steel etc. may not require the same level of cleanliness. ?.3 Inspecting t#e $old fo da%ages& testing 'ilge and fi e s(ste%s ,fter cleaning the hold the following inspections#tests are normally carried out: ?.2 Inspection of the hold for internal damages - e.g. pipe guard, ladder rungs, leaking pipes, bilge sounding striker plates, leaking rivets#welding seams etc. ?.? Testing the Bilge pumping system - This is done if it has not been carried out earlier during washing of the hold etc. :articular attention is paid to ensure that the bilge suction non-return valve is working and

Assignment

:lease submit the following assignment to ,9,. 25 , hold, bale capacity ?333 cu m contains, 2?33 tonnes of bagged flour, 4stowage factor 2.2@ cu m#tonnes5. *alculate the broken stowage. ?5 -escribe a cargo hold preparation in your last ship and state the cargo loaded. 7tate the preparation of hold prior to load general cargo.

ALAM/July 2002

Page #

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

ALAM/July 2002

Page $

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

MODULE - - FACTORS TO CO.S/DER FOR GE.ERAL CARGO STO0AGE

The following must be borne in mind when loading general cargo: 25 *argoes should be well distributed in all hatches to increase the :ort speed. ?5 &oodstuffs and other cargoes liable to tainting - need proper separation #segregation to avoid tainting damage. ;5 !eavier cargo should be placed on deck#tank top whilst lighter cargo on top of these cargoes to prevent crushing damage. <5 It is a general rule that fragile and light packages are stowed in tween deck4s5 to avoid the effects of roll and pitch of vessels. @5 )nsure packages stowed evenly 4not tilting5, for e ample near turn of bilge, end holds by the proper use of dunnage to achieve compactness of cargo stowage. >5 9ight packages 4cartons, etc.5 stowed away from cargo hold obstructions such as frames, deck beams, stiffeners. E5 8aluable cargo should be stowed in strong rooms or in *hief /fficer%s office. =5 To avoid cargoes being crushed during slinging use proper gears like pallet, spreader. G5 :roper securing of cargoes and lashing are essential. ) tra pad eyes may have to be welded to have more securing points for lashing cargoes. turn round% is also dependent on port facilities for clearing the cargo etc.

General Cargo Sto)age

The following points must be borne in mind when planning loading of "eneral *argo by *hief .ate or officer in charge of loading. a5 7afety of the ship stability considerations proper trim#list#draught avoiding structural stresses avoiding physical damage from cargo b5 7afety of the crew and port workers preventing unstable cargo blocks avoiding blocking of escape routes #safety appliances protection from to ic fumes#fire ha+ards c5 ,voiding damage to cargo avoiding condensation#water damage protection from taint # contamination # interaction preventing physical damage to cargo preventing pilferage d5 .a imum use of available space on board minimi+ing Hbroken stowage using Hfiller% cargo e5 (apid and systematic discharging and loading providing ma imum number of working hatches#even distribution preventing over stowed cargo preventing over carried#short landed cargo 4proper segregation#marking5. enhancing Hport speed%

Port S'ee"

)ach day that a ship remains unnecessarily in port results in a reduction of the ship%s earning capacity. ,n unnecessary delay in port increase the port dues allied costs and encroaches on the time that she would have been steaming on her ne t voyage. 7hips officers should aim for increasing Hport speed% by efficient distribution of cargo, readiness of cargo spaces etc. This Hspeed of

ALAM/July 2002

Cargo Plans

, cargo plan is a plan showing the disposition and distribution of cargo throughout the vessel, in as much detail as is possible. , cargo plan for a general cargo ship will usually be drawn up at the last port of loading from information derived from the deck officers cargo workbooks, from mates receipt and from

Page %

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

loading plans produced by shore personnel at the loading ports. *opies of the plan will usually be sent ahead of the ship to the discharge ports. 'hilst the plan is not a scale drawing, it should show with some accuracy the location of specific parcels of cargoes in the locker doors, hatchways so that the order of discharge may be planned 'hilst the format of the plan will vary from company to company, most plans will show the lower holds in elevation 4side view5 and other compartments such as tween decks and deck lockers, in plan view. 'here possible, each parcel of cargo should be identified separately, but this is not always possible when many small parcels are involved 4in which case they are grouped together5. , typical entry on the plan could be as follows: 9%://9#:1" <33 *,7)7 */(1)- B))& C7:,(D ?;t. i.e. <33 cases of corned beef, loaded at 9iverpool for discharge at :enang, all cases marked C7:,(D for identification and the total weight of the parcel is ?; tones. It is usual to colour the plan according to the port of discharge, so that the likelihood of overlooking a parcel of cargo and carrying it to the ne t port 4i.e. overcarriage5 is reduced. In the case of cargo having optional ports of discharge it is coloured in both port%s colours. 'here there is unused space ad$acent to stowed cargo, it is measured up, and the calculated volume measured, and entered on the plan. 8arious symbols and conventions may be used: - for e ample, parcels separated by a diagonal line on a side elevation, are side by side in the hold. In addition to the actual drawing, other useful information is shown in the plan. The name of the ship, master%s name, the voyage number, cargo loaded /1 -)*B, in masthouses, and in various other e traneous places such as the mate%s office and the draft at the last loading port are shown in the cargo plan. It is good practice to append a statement of dangerous cargo on board for quick

reference. , summary of total tonnages loaded in each hold and other information regarding dead light, as fuel, stores and water0 means of separation used between particular parcels and the total space remaining are also appended to the plan. 1ote: The typical cargo plan of a general cargo ship is shown on the opposite page. The cargo plan has a number of functions: it helps to avert overcarriage and short delivery. the discharge sequence can be planned in advantage. the necessary cargo handling gear can be rigged in advance. discharge time can be estimated. transport arrangement for a particular parcel of cargo can be made. proper decisions can be made on ventilation can be arranged with the aid of the cargo plan. in the event of a fire breaking out in the compartment, the cargo plan is invaluable in fighting the fire, particularly if dangerous cargoes are in the compartment. should any cargo shift while the vessel is at sea, prompt action can be taken with the aid of the plan. the plan, enables the shipowner to assess the position regarding to diverting the vessel enroute to load further parcels of cargo.

Cargo Plan On Tan!ers

9ike the cargo ships, the tanker cargo plan is particularly useful when a number of diverse cargoes are to be loaded. 6nlike the cargo ship, it is only necessary to show the disposition of the tanker cargoes in plan view, at one level. It is sometime the practice to overprint the comparable importance. .ost of the functions of the plan are similar to that of the general cargo plan. It is particularly useful to deck officers when loading or discharging to the chief officer for planning tank cleaning and to the chief engineer for maintaining cargo temperature. The cargo plan enables a visual record to be kept of previous cargoes, which is of significant importance to the chief officer when planning the disposition of future cargoes.

ALAM/July 2002

Page &

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

ALAM/July 2002

Page '

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

ALAM/July 2002

Page 10

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

DUT/ES A.D RESPO.S/&/L/T/ES OF CARGO OFF/CERS

Cargo O##i ers

The term H*argo /fficers% implies the person responsible for the safe and efficient handling and stowage of cargo on board. This responsibility also includes the proper preparation of the hold prior to loading, correct supervision during the working of cargoes proper to the preservation of cargo whilst in transit and the co-operation#co-ordination with relevant port authorities whilst in port#harbour. The .aster to the senior most deck officer i.e. the *hief /fficer generally delegates the responsibilities of the *argo /fficer. The ?nd and ;rd /fficers, who are called the HIunior *argo /fficers%, assist the *hief /fficer in carrying out these duties. proper rotation of ports and also ensure that no cargo is over stowed. E5 To undertake measures to prevent the outbreak of fire on board and to ensure that fire fighting equipment is in readiness all the time. =5 To ensure the safe operation of all ship%s cargo handling gears. G5 To avoid damage to the cargo - to ensure the proper handling, slinging, discharging, separation, ventilation, slinging, distribution of cargo. In the case of refrigerated cargoes The proper control of temperature. 235 To take adequate measures to prevent the pilferage of cargo. 225 To maintain a daily check and record of cargo loaded or discharged including the vessel%s draught. 2?5 To make proper and correct entries into the .ate%s 9og Book, issue relevant .ate%s (eceipts for cargo loaded, drawing up of cargo plans, hatch lists, cargo summaries, dangerous cargo lists etc. To maintain the -angerous *argo (egister. 2;5 To attempt a good distribution of cargo at loading and discharge ports, so as to obtain the fastest turn round of the vessel and minimise port stay. 2<5 To ensure that all cargo is properly secured, hatches well battened down and cargo gears secured before the vessel proceeds to sea.

D%ties An" Res'onsibilities

The main duties and responsibilities of the *argo /fficer are listed below: 25 To ensure the proper preparation of all cargo spaces for the types of cargo to be carried. ?5 To inspect the ship%s cargo gear to ensure that it is in good working condition and in accordance with the statutory requirements. ;5 To ensure that all holds, accesses and parts of the ship comply with the requirements of the -ock 7afety (egulations. <5 To ensure proper status of guardrails, manhole covers, side ports, stern doors, container fittings etc. @5 To plan and supervise the proper stowage of cargo on board ensuring the safety of life and property, and avoiding e cessive ship stresses whilst having adequate stability during loading and discharging and at all stages of the voyage. >5 To achieve proper stowage of cargo not in such a manner as to prevent correct and speedy discharge, taking into account the

1#) To ensures that proper ventilation of cargo

spaces is carried out to prevent cargo damage due to condensation#sweat. To check and record temperatures and */? concentrations in refrigerated cargo spaces. 2>5 In the event of bad or adverse weather conditions, to ensure the water tightness of

Page 11

ALAM/July 2002

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

compartments, proper trimming of ventilators and the lashings of cargo etc. 2E5 To ensure that all work on board is carried out in accordance with the C*ode of 7afe 'orking :racticesD. 2=5 To properly delegate duties to Iunior *argo /fficers with adequate instructions for the proper loading#discharging and stowage of cargo and the overall safety of the vessel.

Slinging O# General Cargoes

9oading and discharging of cargo is facilitated by the use of proper cargo handling gears namely, derricks#cranes 4the lifting machines5 and slings. 7lings facilitate the Hgrouping% of unit packages of cargo conveniently for connecting to derricks # cranes. 8arious types of slings, for use with different types of general cargo, are available and are designed to minimise damage to the cargo during the lifting process. 7ome of the principle types of slings, available are clearly e plained in various te tbook.

Pa !aging O# General Cargo

"eneral cargo may be presented for shipment with various forms of packaging, such as: Bags - made from natural fibres like $ute#cotton or from synthetic fibres and paper. 6sed for cement, grain, sugar etc. They are liable to bursting at their seams. Ca tons - made from cardboard. 6sed for finished goods like condensed milk, shoes, or for carrying fruits etc. They are very fragile and liable to be crushed. C#ests - rectangular#square bo es made from plywood. 6sed for carrying tea. They are fragile and liable to be crushed. Cases - rectangular bo es made from wooden planks nailed and banded. *an be strong or fragile depending on quality of wood J construction of case. 6sed for heavier goods like spare parts etc. or to protect fragile goods. C ates - rectangular, made from wooden planks with Hgrated% design. 1ot as strong as cases and sides are fragile. 6sed for machinery parts etc. Bales - formed when commodities such as natural fibre, cloth etc. are pressed tightly into a rectangular bundle and then strapped firmly with metal bands or cord. 9ifting by hooking onto bands should be avoided. Ba els - made from shaped wooden planks called Hstaves% and held by metal hoops. The weakest part is the rounded middle called the Hbilge% and the strongest is at the quarter hoop%. The opening for filling the contents is called the Hbung%. Ideally placed on wedges, called Hquoins% placed below the quarter hoops keeping the Hbilge off the ground and the Hbung% upwards 4i.e. HBung up and bilge free%5. 6sed for carriage of wine etc. and similar produce.

Uniti1ation2Palleti1ation

To further facilitate quicker dispatch of cargo into#out of the ship, and to allow it to be handled mechanically by machines such as forklift trucks, small packages of cargo 4unit packages5 of uniform si+e are sometimes consolidated into Hunit loads% on Hpallets% 4double-layered wooden platforms of standard dimensions capable of being lifted conveniently by fork lift trucks5. 7pecial Hpallet slings% make the slinging of pallets, onto derrick#cranes, faster and easier. The concept being to assist the process of cargo handling by reducing the number of occasions when a piece of cargo has to be manually handled thereby increasing cargo throughout.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 12

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

Can ,oo!s

The hook slips under the lip of the drum or barrel. There are frequently four or five sets of hooks on a ring, which enables drums and barrels to be handled very rapidly. They are not to be recommended for handling heavy barrels as there is a possibility that the staves will be pulled out.

Snotter

H:re-slinging% of cargo, where slings are left on after loading so as to facilitate quicker discharge at the other end 4by avoiding the building up of sling loads again5 is a form of uniti+ation and is used on some trades. H*ontainerisationD is a special form uniti+ation and will be discussed later. of

.ay be made of either rope or wire by forming an eye at each end of a 2>mm - ?3mm wire 4?D - ?.@ C5 or @3mm - >3mm rope 4>D - ED5 < to > metres 4?-; fathoms5 in length. It is used for slinging cases, bales, wet hides and timber.

&AS/C CARGO ,A.DL/.G E3U/PME.T A.D CARE OF CARGO C*ain Sling

Plate Clam's

*onsists of a length of chain with a large ring at one end and a hook on smaller ring at the other end. It is used for lifting heavy logs, bundles of iron and most steel work. *are must always be taken that no kinks are allowed to form in the chain when goods are being lifted.

There are various type o plate clamps, but the principle is that the plate is gripped when the weight is taken, so that there is no chance of plate slipping as it could do if a chain sling was used.

Page 13

ALAM/July 2002

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

Ro'e Sling

This is formed by $oining the ends of a piece of ?@mm - ;3mm rope ;D - ;.@C5 about 23 to 2? metres 4@ to E fathoms5 in length with a short splice. The sling is in very common use. Bags, baled goods, barrels and cases may all be along with this.

This is formed by sewing a piece of canvas between the parts of a rope sling. It is used for bagged grain, rice, coffee and similar cargoes where the contents of the bag are small. ,ny spillage is retained in the canvas and is not wasted. The stress on the outside bags is spread more evenly and thus the chance of splitting is reduced.

DAMAGE DUE TO /MPROPER USE OF CARGO ,A.DL/.G E3U/PME.T

.uch cargo damage results from careless or improper handling during the loading and discharging processes, the following being the principal sources of such damage: -

&o4es

Careless 0in * 0or!

9owering heavy slings or drafts of cargo too fast on to cargo already in stowage not infrequently is responsible for damage which, often goes undetected until discharge.

Cargo ,oo!s

7imilar to the tray by a wooden side is fi ed around it. 6sed for handling e plosives. The use of these implements is indispensable in the handling of a large variety of commodities, but with bag cargo, fine bale goods, hides, fire rolls of paper and matting, etc., light packages, liquid containers, crates and like packages whose contents are e posed or unprotected, the use of cargo hooks should be strictly prohibited.

Tra(s

Cro) an" Pin * &ars

These also are indispensable to the sound stowage of many classes of heavy packages, but their use should never be permitted when stowing barrels, or other liquid containers, or with any packages which are not substantial enough to withstand damage from their use. .ay be square, rectangular or round. They are slung by pieces of rope called legs, attached to the corners. 6sed for small cases and drums.

Cr%s*ing against S*i'5s Si"es

!atch coamings, beam sockets, etc., should be safeguarded against by the use of overside skids, the correct plumbing and guying of derricks, and careful winch driving, especially when swinging booms are in use.

Canvas Sling

ALAM/July 2002

Page 1!

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

Dragging Cargo

-ragging *argo by winches along the deck to save trucking, from remote ends and wings of holds and Htween decks instead of making up the CdraftD or CslingD near the hatch, is a prolific source of damage to, and loss of contents of the lighter class of packages, as well as to the cargo in stowage over which such is dragged.

crushing the outside upper packages by compression of the sling. 9ight or fragile packages should not be slung along with heavy packages.

La ! o# 0al!ing &oar"s

9ack of 'alking Boards and landing platforms. 'here these are not provided and used, damage is caused to packages, in towage, over which other cargo has to be worked into the position where it is to be stowed. :ackages, which are damaged after they are at Cship%s riskD, should be carefully recoopered or repaired before stowing away.

Dro''ing Pa !ages

-ropping packages from trays, trucks, railway cars, top tiers of lighters, etc., by which their contents are broken or e posed, the packages splintered, deformed or loosened in their fastenings and rendered unfit for the subsequent handling they are sub$ected to. To avoid this, suitable skids should be used for packages, which are too heavy to be handed down.

S0EAT A.D +E.T/LAT/O.

+) ,-E.T a5 C7weatD is condensation, which forms on all surfaces in a cargo compartment due to the inability of the cooled air in the compartment, to hold water vapour in suspension 4warm air can hold much more water vapour than cool air5.

/m'ro'er A''lian es

The use of special appliances tends to be e peditious and economical in handling of cargo, but damage is frequently caused by the improper use of such appliances. 1et slings are most useful with many kinds of small packages, but if used with bagstuff, light cases, etc., a great deal of damage results. 7imilarly chain slings are indispensable for certain types of packages and useful for most classes of iron goods, but the use of such with light cases, sheet iron, coils of lead or copper piping, sawn logs of valuable timber and other goods liable to buckling, fraying or marking by chain is productive of damage and claims. *anvas or web slings should be used for slinging bag flour, coffee and like cargo, while the use of trays for certain classes of goods is much to be preferred to slinging by net or rope.

/m'ro'er Slinging

Too much weight in a draft endangers the safety of packages situated at the outside edge of bottom and top tiers into which the sling is liable to be drawn by weight below and compression above. , draft composed of many packages should taper off on top to prevent springing or b5 7weat may be differentiated as follows:

ALAM/July 2002

Page 1#

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

i5 7hip%s 7weat - e ists when water droplets are deposited onto the ship%s structure in the compartment 4e.g. deckheads, beams, frames, shipside, stringers etc.5 and then fall onto or come in contact with the cargo. It occurs when the dew point of the air in the cargo compartment is more than the temperature of the outside air#structural parts of the compartment. It is usually found on voyages from warm places to colder places. ii5 *argo 7weat arises when condensation forms directly on the body of cargo itself. It occurs when the temperature of the air in the compartment 4or the cargo itself5 is lower than the dew point of the incoming air. It is likely to be found on voyages from cold to warmer places. c5 :revention of -amage by 7weat ,lthough intelligent use of dunnage can minimise damage from sweat, it is more prudent to consider the prevention of damage by the elimination#minimisation of sweat by efficient ventilation. The controlling factor for the formation sweat is the relationship between the temperature and humidity of the air in#outside the compartment. ,ir having 233A humidity is said to be Csaturated the temperature at which this occurs is called its dew point.

removing fumes and odours emanating from cargoes stowed in the compartment to prevent Htaint% or other damage. thus preventing fire.

b5 8entilation may be described as either: )i T# o"g# 0entilation - with the flow of air occurring through the body of the cargo assisted by proper Htrimming% of ventilators and the $udicious use of dunnage.

)ii

," face 0entilation - with the flow of air occurring only at the upper surface of the cargo and not being forced into the body of the cargo. c5 8entilation may be provided by two ma$or means: i) Nat" al 0entilation - this is achieved by Htrimming% the ship%s ventilators and obtaining a natural flow of air caused by the vessels movement or outside wind. Trimming the leeward ventilation into the wind and trimming the winward vents away from the wind can effect HThrough natural 8entilation%. The air in the compartment will then move in a direction contrary to the flow of outside air.

i) 'hen the dew point of the outside air is

lower than or equal to the dew point of the air in the compartment - 8)1TI9,T). )ii 'hen the dew point of the outside air is greater than the dew point of the air in the compartment - -/ 1/T 8)1TI9,T). /) 0ENTIL.TION a5 8entilation has the main ob$ectives of: preventing moisture damage to cargo originating from condensation 4sweat5 within the cargo compartment.

ii)

Mec#anical o 1o ced D a"g#t 0entilation - The simplest of such systems consists of a fan of appropriate si+e and design which delivers outside air into the compartment, and the used air from the compartment is discharged to the atmosphere via the natural e haust ventilator.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 1$

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

7ometimes such an arrangement does not prove satisfactory and hence the e hausting is also done mechanically by means of a suitable e haust fan. The delivery and e haust is properly balanced to provided good airflow.

side frames with the distance between the Hbattens% of about ?;3mm 4GD5. *argo battens are sometimes fitted vertically and in such cases the initial e pense is generally greater. !owever there tends to be less subsequent damage to the battens and better protection is afforded to the cargo.

The tank top is usually covered with a double layer of non-permanent dunnage called Hportable dunnage%. The bottom layer consists of @3mm @3mm 4?D ?D5 timber spaced about 3.E to 2.3 metre 4?-; feet5 apart and laid athwartships - if the ship has conventional side bilges 4otherwise laid fore-and-aft in case of Hbilge wells%5 to allow free drainage. The upper layer consists of 2@3mm ?@mm 4>D 2D5 boards laid across the lower layer, about ?;3mm 4GD5 apart. 2) D3NN.GE -unnage% may be referred to as the wood that is used to protect cargo. It may be in the form of wooden planks, or slats, bamboo, bamboo or rush mats. In some ships the tank top, in way of the hatch, is protected from impact damage by cargo by a permanent wooden sheating called the Htank top ceiling%. This does not replace dunnage and the portable dunnage should be laid over this and it should also e tend over limber boards. 7imilar dunnage arrangements will be found in the tween decks, however the lower layer of portable dunnage may also consist of 2@3mm ?@mm boards 4sometimes only a single layer is used5. :articular attention should be paid at the shipside stringer, where a thicker layer of portable dunnage may be prudent, as water tends to accumulate here. .any general cargo ships have permanent dunnage, called Hspar ceiling% or Hcargo battens%, fitted over the side frames in the hold 4and sometimes over the bulkhead stiffeners5. It consists of 2@3mm @3mm 4>D ?D5 timber usually fitted hori+ontally into cleats over the Timber used for dunnage should be clean, dry, stain free, odour free and free from nails and large splinters. 1ew timber should be free from resin and the strong smell of new wood.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 1%

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

'ith some cargoes such as bagged rice etc, the hold pillars should be lagged with bamboo mats. 'hen battens are not fitted on bulkhead stiffeners, a lattice of bamboos may have to be erected as a temporary measure. It must be noted that dunnage need not be laid if the cargo does not require ventilation. &or e ample, when coal is loaded in bulk, the cargo battens are removed and no portable dunnage is laid. The use of dunnage may be summarised as: :reventing cargo coming into contact with free moisture#water on the tween deck or tank top. :reventing cargo from coming into contact with the steel boundary of the hold thus minimising damage due to Hship%s sweat%. ,ssisting in providing ventilation, thus preventing # reducing Hsweat%. :reventing spontaneous heating by affording good ventilation. ,iding distribution of weight over a layer of cargo thus minimising crushing damage to cargo. :reventing chafage between cargoes. *ertain types can prevent pilferage of cargo. ,iding in distribution of cargo weight over tank top etc. *an be used to separate cargoes 4this is not considered as a normal practice5.

These definitions include pump rooms on tankers. There may be special instructions for routine entry into pump rooms on your ship. .ake sure you know what they are. .N ENCLO,ED ,!.CE ,$O3LD NE0ER BE ENTERED 3NLE,, .3T$ORIT4 $., BEEN GI0EN B4 T$E M.,TER OR . RE,!ON,IBLE O11ICER The atmosphere in any enclosed space may be incapable of supporting human life. It may contain flammable or to ic gases or not enough o ygen. This is why it is essential that the .aster or officer in charge, who will ensure that all the necessary safety precautions have been taken before anyone is allowed to enter an enclosed space, must give instructions or permission.

Pre a%tions &e#ore Entering Tan!s Or Con#ine" S'a es

25 :rior to entry into enclosed space it is essential to obtain permission first. ?5 Test on tank atmosphere - should be checked by using e plosimeter and o ygen analyser where appropriate for safe entry. ;5 8entilate space prior to entry and continuously during the operation so as to ensure the environment is safe. <5 )ntry should be restricted to the minimum number of personnel required for the $ob and a record is made on the number of personnel. @5 ,dequate lighting to be provided for the entry. >5 :roperly attired and safety gear should be observed by all personnel involved in the entry into enclosed spaces. E5 6se only intrinsically safe equipment when the enclosed space was used to store or carry flammable cargoes prior to the entry. =5 :ost signs at entrance and one competent man on standby to monitor the operation. G5 :roper and effective communication established between all parties involved in the entry. 235 )mergency procedures and evacuation should be briefed and well understood to all personnel involved.

Page 1&

Entr( /nto En lose" S'a es

There are many enclosed spaces on a ship - if in doubt about any space you may have to enter *!)*B &I(7T with *hief /fficer.

An En lose" S'a e /s

any space or compartment that has been

closed or unventilated for some time. any space or compartment that may, because of the cargo carried, contain no ious, flammable or harmful gases. any space or compartment which may be contaminated by cargo or gases leaking through a bulkhead or pipeline. any storeroom or space containing no ious or harmful materials any space or compartment which may be deficient in o ygen.

ALAM/July 2002

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

?5 -escribe ship sweat and cargo sweat and the factor affecting sweat.

Assignment

:lease complete the assignment and return to ,9,. 25 7tate the functions of a cargo plan in a bulk carrier.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 1'

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

MODULE 6 - CO.+E.T/O.AL DERR/C7 R/GS

T*e Single S)inging Derri !

The single derrick rig is basically a boom supported at its base 4heel5 by a special pivotal arrangement called the Hgoose neck%, which allows it to be raised or lowered by means of a Htopping lift span% and to be swung from side to side by means of Hslewing guys%. 1ear the head of the derrick boom is the Hspider band% onto which are attached the Hderrick head span block%, the Hslewing guy pendants% and the Hcargo head block%. The topping lift span, downhaul 4the hauling part5 is led via the Hmast head span block% on to a Hdolly winch% usually fitted with its own motor for the sole purpose of raising#lowering the derrick boom 4in order ships the daily winch may have no motive power of it%s own and is turned by using a Hbull wire% onto the side drum of the cargo winch. , safety device in the form of a Hpawl% is fitted to the dolly winch to prevent the accidental lowering of the derrick boom.

The Hcargo runner% downhaul is led from the Hcargo head block% to the cargo winch via the Hderrick heel block% and usually passes through a Hrunner guide% on the boom, which prevents the runner from sagging. The slewing guys 4fitted on each side of the boom5 which have their wire pendants shackled to the spider band at the derrick head have their lower parts consisting of a cordage tackle for hauling on. The single derrick rig can be used to lift loads to the full e tent of it%s 7'9 4safe working load5, which is marked near the heel of the boom, provided the cargo runner 4or cargo purchase5 is also rated to that 7'9. NOTE: When a single derrick is used in the Union Purchase rig, a preventer guy is passed over its head on the out oard side. , single swinging derrick which converts a single whip to a double whip and creates a mechanical advantage. 6sed to lift load double of the 7'9 of the cargo runner 4The derrick must be rated higher5.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 20

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

YO-YO Gear

)mployed using two or four single derricks. 6sed for loads heavier than those, which can be handled by the union purchase or single swinging derrick.

T)o Derri !s

The two inshore derricks are rigged with a gun tackle and their moving blocks are $oined by a heavy strop supporting a floating block 4K/K/5 with the cargo hook attached. /peration is carried out by swinging both derricks towards the hatch#quayside, keeping both derricks heads as close together as possible.

Fo%r Derri !s

Two pairs of derricks are rigged similar to the union purchase. The two cargo runners of the inboard derricks are passed through a floating block and shackled together0 similarly the outboard derrick runners are passed through another floating block and shackled together. The floating blocks are then shackled together to form the union with the cargo hook secured below them.

a union hook and worked in con$unction with each other. Refe to fig5 .. )ach cargo boom is $oined to the vertical mast or post by a swivel fitting known as a goose neck 4so named because of the shape of the fitting5. Then up and down, or luffing, movement as the boom is carried out by a topping lift#span tackle, and the hori+ontal or athwartships movement is controlled by a slewing guy attached to the outboard side of the boom head. The two booms are linked by a schooner guy which runs from the inboard side of one boom head to the other and thence to the deck via a lead block on the mast. Inboard slewing guys sometimes replace the schooner guy but the latter tend to interfere with the cargo-working operation. The schooner guy is always well clear of the cargo working area. The guys and tackles position the derricks. /ne boom is positioned over the hatch and the other boom is positioned over the ship%s side. 'hen the booms are set up in position the preventer guys are set up tight. These are single lengths of wire which lead from the outboard side of the boom to the deck and which have the function of taking the guy load during the cargo-handling operation. The preventer guy is sometimes called the standing guy as it has no moving parts whereas the slewing guy consists of a tackle 4usually the only tackle on board ship rigged to advantage5. , cargo wire, or runner, from each boom is $oined by a three-way swivel which is known as a union hook. In the unloading process the boom centred over the hold lifts the load by its runner. /nce the loadline has been lifted to a sufficient height to clear deck obstructions, the cargo runner from the other derrick is used to move the load over the ship%s side and on the quay or into a lighter.

DERR/C7 R/GS Union P%r *ase S(stem

&ig. , - 6nion purchase rig !sle"ing guys not sho"n# This is probably the most common derrick system in use on general cargo vessels. Two derricks are CcoupledD, CmarriedD, or $oined by

Page 21

ALAM/July 2002

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

load, by the topping lift span led to a separate winch, and it can be swung from side to side 4slewed5 by Hsiean guys% or either side led to separate winches. In view of the greater 7'9, the topping lift span0 the cargo fall and the steam guys are all multiple-fold purchases. &urther the cargo purchase and the topping lift purchase are rigged advantage 4by use or additional Hlead% sheaves5. In view of the heavy loads involved and the si+e of the rig, great care is required for setting it up 4which may take up to ? - ; hours5.

PATE.T DERR/C7S &asi C*ara teristi s Pre a%tions

The following criteria must be complied with at all times: 5a The minimum operating angle of either derrick should be not less than 2@L to the hori+ontal, and it is recommended that the angle be not less than ;3L0 5b The ma imum included angle between the cargo runners must not e ceed 2?3L0 5c The outreach beyond the midship breadth of the ship should not less than <m. The main advantage of this system is that it is probably the fastest method used for discharging break-bulk, non-uniti+ed general cargo. i5 The twin topping lift#slewing guy principle is used which gives good control of a single derrick. ii5 The capability of handling heavier loads than the union purchase system. iii5 *ombined slewing and topping 4luffing5 tackles. iv5 8ery good spot loading facilities. i.e. the load can be set down in most positions within the hatch area. v5 , high degree of centrali+ed control with the operation being conducted by one man. vi5 The derrick is rigged at all times and can quickly be brought into operation. vii5 The use of new technology reduces the stresses encountered with the union purchase system. There are many patent derrick systems used on board ship but the best known are probably C!allenD and C8elleD for the handling of general cargoes and C7tuelckenD for heavy lifts.

Disa"vantages

a5 It can only be used for light loads, an average of appro imately 2.@ - ? tonnes per load. b5 The winchmen must be highly skilled and e perienced. c5 The derricks cannot be used for Cspot loadingD. d5 (e-positioning the derricks is timeconsuming.

T*e 8%mbo Derri !

This is basically a single swinging derrick with a much greater 7'9 4about ;3 - @3 tonnes5. The boom can be raised or lowered, with the

Page 22

ALAM/July 2002

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

,allen Derri !

when swung out over the ship%s side to an angle of =3L from the fore and aft line. The frame also helped to keep the derrick stable in all positions, even when the vessel had a list. !owever, under some operational conditions there were disadvantages when using the frame: 25 'hen the derrick was swung outboard, the sharp angle created by the contact of the topping lift guy pennant with the frame caused e cessive strain in the topping lift. ?5 There was a tendency fro the single-wire pennant on the topping lift to slip above or below the frame when working at CdifficultD angles, once again putting e cessive strain on the topping lift. ;5 The contact with the frame caused chafing on the pennant. This was reduced by fitting rollers to the frame or by protecting the wire. The - frame has been largely replaced by outrigger rods. 4fig. ;5 which are pivoted, and are stayed on the outboard side only so that the rod nearest the discharging side can swing towards the ship%s side, thus ensuring a wide separation angle of the topping lifts. ,s with other patent derricks, such as 8elle and 7tuelcken, the 8-shape arrangement of the topping lifts gives a broad base which is necessary for lateral holding and guiding of the derrick. In figure ; the broad base between the topping lifts is provided by a cross-tree at the mast head. It could also be provided by derrick posts, gate masts, or 8 masts. In the !allen system each topping lifts runs to its own winch. !auling on both winches tops the derrick, and if one winch hauls in while the others pay out, the derrick slews to the side of the ship on which the hauling winch is located. a third winch is used for hoisting and lowering the cargo. The derrick is controlled by two levers. /ne lever operates the cargo, purchase and the other lever has a multiposition control for the topping and slewing operation.

The !allen swinging derrick employs the twin topping principle which allows good control of a single derrick. This derrick was originally designed for loads of @ - = tonnes but loads of over 233 tonnes are now une ceptional. The derrick can be mounted on all types of mast or derrick post and can make a traverse from port to starboard of 2>3 - 2=3L.

In the original design a fi ed frame CoutriggerD was fitted to the mast 4as in fig. B5 which was commonly known as a C-D frame. This had the effect of keeping the topping lifts at a sufficiently wide angle to one another to ensure the derrick remaining steady even

+elle Derri !

The 8elle swinging derrick also uses three winches. The cargo purchase is operated by a standard type winch but the topping lifts are arranged so that one of the other two winches

Page 23

ALAM/July 2002

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

controls the luffing while the third winch is used solely for slewing. )ach of the topping lift winches has a split or divided barrel on to which the ends of falls are secured. /n the luffing winch the falls are laid on to the split barrels in the same direction. Thus both falls will hoist or lower the derrick simultaneously. /n the slewing winch the falls are laid on to the split barrels in opposite directions. Thus when the barrels rotate, one fall pays out while the other heaves in and the derricks slews to port or starboard. The topping lift luffing and slewing winches are operated by a multiposition control lever which is positioned ad$acent to the cargo purchase control lever. The operator stands between the levers and operates the cargo purchase with his left hand and controls the derrick movements with his right hand. &igure * shows a plan view of an early version of the 8elle derrick in which a bridle bar was used to spread the topping lift spans at the derrick head. The bridle bar evolved into the CTD- shaped derrick head shown in &igure @. Both arrangements make very wide slewing angles possible due to the good lateral stability achieved by the spread of the spans at the derrick head. The derrick can be swung outboard until it is almost perpendicular to the ship%s side, even with an adverse list. :endulous swinging of the load has been a ma$or problem with derricks in which the load hangs a Csingle pointsD. "ood load stabili+ation is achieved with the T-shaped derrick head as the spread of the cargo runner reduces pendulous swinging and load rotation. The 8elle derrick is noted for its comparatively simple design, reliability, and versatility. The standard designs operate up to a capacity of appro imately ;@ tonnes but heavy-duty designs are capable of lifting appro imately 233 tonnes.

;5 *ontact with frame cause chafing. (educe by fitting rollers.

T)o Levers

25 /ne operates the cargo. ?5 /ther 4multi-position5 for topping J slewing position.

S,/PS CARGO DEC7 CRA.ES

7ome modern ships are fitted with cranes instead of derricks. Basically they are provided with individual electrical driven motors to permit lifting of the HIIB%, slewing of the $ib and the working of the cargo hoist. The HIIB% is a pro$ecting hinged arm and is usually of the luffing type which allows it to ensures hat the hook carrying the weight remains at the same level. The lifting wire rope is rigged usually as a single whip. It leads over a sheave at the head of the $ib and is called the purchase. Between the purchase and the hook is a weight called the Hponder ball%. Its function is to help the purchase to over-haul when there is no load. The crane may be set to move on rails the ship or along the ship or may be fi ed centrally with a large reach and angle of slew. *ranes offer the following advantages: greater Hspotting area% particularly when installed on the vessel centre line, providing greater fle ibility. faster loading#discharging rate. less time in preparing for operations. decks clear of guys, stays and other standing#running riggings. self contained and easier to operate. The main disadvantages of the crane are its higher initial cost and the possible pendulous swinging of the load when slewing is done in a fast manner.

Disa"vantages o# 9D5 #rame

25 'hen swung outboard, sharp angles created by topping guy with frame cause e cess strain in topping guy. ?5 ,t difficult angles single topping pennant to slip above or below C-D frame - e cessive strain.

Derri ! Testing

7hip%s derricks are initially tested 4initial test5 with the boom at an angle of not more than 2@L to the hori+ontal or, if this is impracticable, ;3L.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 2!

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

-uring its working life, it is recommended that the derrick be retested after any repair to the derrick or permanent fittings, or after any alteration of the rig is not covered by the ship%s plan. 'hen carrying out a test, the -ecks (egulations, form GG should be consulted, to ascertain whether the accessory gear complies with the statutory requirements. If all is in order, the test may be carried out0 otherwise, all loose gear, blocks, shackles, etc., should be sent to works for the necessary treatment in accordance with the statutory requirements laid down in form GG. The safe working load of the derrick Has rigged% should be checked by reference to the individual safe working loads of the blocks and shackles in the rig, either by direct calculation, or by the preparation of load diagrams. The strength of the wire ropes in the cargo and span purchases should also the checked for the required factor of safety. If any items of gear are found to be of insufficient strength, either they should be replaced by gear of the appropriate si+e and strength, or the safe working load of the derrick reduced. Tests are generally carried out by the use of loads 4known as a Hdead load test%50 or by the use of a dynamometer 4test clock5. It is preferable that the Hinitial test% be carried out by Hdead load%. If no particular derrick a single whip is normally used but the derrick boom and span gear are capable of supporting a cargo load greater than that which may be lifted by a single whip, a proof load may be applied with the cargo runner double up at the derrick head, provided that the ship%s blocks and shackles are used for the test. 'here it is found necessary to use the doubling-up method 4i.e. a gun-tackle rig5, this should be stated on the certificate of test, also the safe working load that may be lifted on a single whip. 'hen a derrick is rigged with a cargo purchase, and the hauling part of the purchase

is parallel to the boom, the safe working load marked on the upper block in the purchase should be greater than that marked on the lower block. This takes into account the increased resultant load due to the tension in the hauling part of the purchase. Before applying a proof load to the derrick, all permanent attachments on the mast and derrick should be carefully e amined. It is also good practice to rig an adequate preventer span wire rope as a precautionary measure against any part of the span gear Hcarrying away%. This additional span wire rope should not take the mass of the mass of the derrick during test. 'hen proceeding with the test, the proof load should be applied steadily, and all fittings should be carefully watched for any indication of failure. ,part from watching, it is also desirable to Hlisten% for any signs of failure. 'hen testing heavy-lift derricks, care should be taken to ensure that the anchorage for the test clock is of adequate strength, avoiding any risk of structural damage to the ship. &or derricks of ;3 t safe working load and over, it is advisable to lift moving loads or use a specially designed anchorage on the vessel, and to ensure that there is sufficient stability to avoid e cessive list under test. It is also important that shrouds and preventers are properly set up to give adequate support to the mast. &urthermore, slewing guys should be so placed that the angle they make with the derrick boom is not unduly narrow, so that when the vessel heels over under load, they will control the derrick without developing e cessive tension. /n completion of the test, a final visual e amination of all parts of the derrick rig, and of all permanent attachments on the mast and derrick, should be made before issuing the certificate of test and e amination. In all cases the winches should be carefully e amined to ensure that they are in good working order, and that the controls act effectively. Information to this effect should be noted on the certificate of test and e amination.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 2#

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

)very derrick boom should be clearly marked with its safe working load. , certificate of test for this safe working load is required for the derrick Has rigged%, and further certificates of test are required for the individual blocks and shackles in the rig, including such items as guy blocks, chain stoppers, etc. The appropriate statutory forms should be used. In the case of wire ropes, a breaking load test 4form =E5 is required. , copy of the -ocks (egulations, form GG, containing all the prescribed particulars, together with copies of all the appropriate certificates should be kept on board.

,ll beams used for hatch covering to have suitable gear for lifting on#off without persons having to go upon them to ad$ust. ,ll hatch covers to be marked to indicate deck, hatch and position unless covers are interchangeable. ,dequate handgrips on hatchcovers. 'orking space around hatch at least ? ft.

Part 6: Tests Et : O# Li#ting Ma *iner(

,ll lifting machinery to be tested before

DOC7 REGULAT/O.S S%mmar(

,pply to the process of loading, unloading, moving and handling goods on any wharf, quay or ship.

Part 1: Sa#et( Meas%res At Do !; 0*ar# An" 3%a(s

25 &encing. !eight of fence not less than ?% 3>D 43.E>m5. ?5 97, in readiness at wharf or quay. ;5 )fficient lighting. <5 &irst aid bo es, ambulance facilities whereabouts indicated by notices.

Part -: A ess To An" From S*i' An" Part O# T*e S*i's

,longside quay: ,ccommodation ladder properly secured -

??D wide, fence each side to height of ?% 3GD. ,longside other ship 7afe means of access, provided by vessel with the higher freeboard. ,ccess to holds etc ,pplies where hold depth e ceeds @ ft. 9adders in line 9adders provide foothold to depth of not less than <MD for width of 23D and a firm handhold - *argo to be stowed so as to leave this clearance. )fficient lighting in holds, on decks, in accessways and all parts where persons employed may go during the course of their work. !atchcovers

being brought into use and e amined by a competent person. ,ll derricks and attachments to masts and deck must be inspected every 2? month and thoroughly e amined every < years. /ther lifting machinery thoroughly e amined at least every 2? months. 4Through e amination F visual e amination and hammer test or similar dismantling if necessary5. *hains, rings, hooks, shackles, swivels and pulley blocks used in lifting and lowering must be tested and e amined before being brought into use. ,nnealing or similar treatment - M C or smaller at least every > months, other at least every 2? months.4Thorough e amination F visual e amination and hammer test or similar dismantling if necessary5. "ears to be inspected before use, unless previously inspected within last ; months. (opes to be of suitable quality and free from obvious defect. 'ire rope to be tested before being brought into use, inspected every ; months and if any wire in the rope is broken, every month. If number of broken wires in a length of = diameters e ceeds 23A of total wire in the rope, it must not be used, nor if it shows signs of e cessive wear or corrosion. 7'9 to be marked on blocks and on ring attached to chain sling. *hain#'ire slings not to be shortened by tying knots in them. .achinery to be securely fenced. 7afe access and fencing to crane cabs and driver%s platform. 7'9 is to be marked on derricks and cranes. ) haust steam not to obscure any part of deck or access.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 2$

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

.ethod of preventing foot of derrick being

lifted out of socket.

Part =

1o person to interfere with gear, etc.

Part <: Mis ellaneo%s R%les

.eans of escape from hold or tween deck

where coal or bulk cargo is being worked. 1o winch drivers or signalmen under 2> allowed. 'alking space around cargo stacked on quay. If hold depth e ceeds @ ft. it must be fenced to height of ;ft unless coaming is ?% 3>D. If working cargo in T#- at least one section of hatches to be in place. 7ignaller to be employed.

unless authorised. /nly authorised access to be used. 1o person to go upon beams to ad$ust them.

Part >

If shipowner fails to comply with safe

access regulations the duty to do so falls on employer of the persons employed. (egister to be kept available for inspection.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 2%

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

DOC7 REGULAT/O.S - TESTS A.D E?AM/.AT/O.S

Ever( )in * an" all a essories t*ereto

Test - :roof load in e cess of 7'9 as follows: 7'9 less then ?3 Tons - ?@A in e cess 7'9 ?3 - @3 Tons - 7'9 N @ Tons 7'9 over @3 Tons - 23A in e cess .ethod - )ither weights or spring#hydraulic balance. 4-K1,./.)T)(5. )stimates of the stresses involved may be made by resolution of Hparallelograms of forces% and in some cases by use of empirical formulae. +) In t#e ,ingle ,6inging De ic) The main areas of stresses, when lifting a load by a single derrick would be: a5 the stress on the hauling part of the cargo runner#tackle. b5 the resultant load on the cargo head block. c5 the tension in the topping lift span. d5 the resultant thrust on the derrick. e5 the resultant load on the heel block. f5 the resultant load on the mast head span block. 8arious factors are considered when making estimates of derrick stresses, and for a basic understanding, an e ample is e plained with the rig parameters given below: C, single swinging derrick boom, 2>m long and weighing 2 tonne, makes an angle of >3 to the hori+ontal when suspended by a single span topping lift with the mast head span block secured 2;m above the heel. , load of @ tonnes is to be lifted using a guntackle rigged to disadvantage, secured at the derrick head, with its hauling part led parallel to the derrick to the winch via a heel block. The heel of the derrick is ;m above the deck, and the winch point is ;m from the mast and ?m above the deck. The lifting gun tackle itself weighs 3.? tonnesD. a) Esti%ating t#e ,t ess on t#e $a"ling pa t of t#e Lifting Tac)le This is obtained using the formula: n' '+ 7F 23 : 'here 7 F stress on the hauling part ' F load to be lifted

Ever( rane2"erri ! an" all a essories t*ereto

Test - ,s above .ethod - 'eights swung as far as possible each way and for crane with variable $ib at ma imum and minimum radii as well. -erricks to be positioned at lowest working angle.

Loose Gear 0*et*er A essor( Or .ot

Test - :roof load as follows: *hain, ring, hook, shackle or shivel - ? 7ingle sheave blocks - < 7'9 .ultiple sheave blocks: 7'9 less than ?3 Tons - ? 7'9 7'9 ?3 - <3 Tons - 7'9 N ?3 Tons 7'9 over <3 tons - 2M 7'9 7'9

) amination - ,fter test of all gear, including dismantling of blocks to see that no damage or deformation has occurred.

0ire Ro'es

Test - 7ample tested to destruction. 7'9 not to e ceed 2#@th of breaking load.

STRESSES /. DERR/C7 R/GS

To avoid the possibility of accidental failure 4breakdown5 of derrick rigs, due to overloading, it is essential to know the stresses likely to be e perienced by the various parts of the rig when lifting a load.

ALAM/July 2002

Page 2&

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

n F number of sheaves in the system including lead sheaves : F theoretical :ower "ained 4..,.5 4a Hfrictional allowance% of 2#23 of the load, for n' every sheave, is normally used hence 23 Therefore in the e ample: 4 ? @5 @+ 7F 23 ? ..,. of "untackle F ? 4disadvantage5

>3 2 23 ? 1o. of 7heaves F ? F ; tonnes

the weight of the lifting tackle suspended

from the derrick head part of the weight of the derrick boom 4it is usual to take this as M the weight of the boom5. ,s given in the figure, this is resolved by e tending the vector -* 4representing the load to be lifted5 by a scaled amount *) equal to the sum of the weight of the lifting tackle and M the boom weight 43.? N 3.@ F 3.E tonnes in this e ample5 and drawing )& parallel to the topping lift span 4parallelogram -)&"5. The tension in the topping lift span is then represented by the scale value &) 4;.< tonnes in this case5. d) Esti%ating t#e T# "st on t#e De ic) The forces which produce the thrust on the derrick boom are: the tension in the topping lift span the resultant load on the cargo head block This is represented by the scaled value of ,&, which is equal to ,- N -& 423 tonnes in the case5. e) Esti%ating t#e Res"ltant Load on t#e $eel Bloc) The final load on the heel block results from the stresses in: the cargo runner, acting in the direction of the cargo head block, and the cargo runner, acting in the direction of the winch In the e ample, the stress in the direction of the cargo head block is ; tonnes 4as determined in para 24a55 whilst the stress in the direction of the winch would be ;.; tonnes 4allowing for 2#23 of the load for friction in the heel block - using the empirical formula for stress on the hauling part with three sheaves5. The forces are then resolved using the Hparallelogram of forces% 'OKP, where OK F scaled value of stress towards the derrick head and O' F scaled value of stress towards the winch.

NOTE7 If a single ca go "nne (single 6#ip) 6as "sed fo lifting& instead of t#e g"n-tac)le& t#e st ess on t#e #a"ling pa t 6o"ld #a*e 'een +/+8 of t#e load %o e t#an t#e load itself - allo6ing fo f iction in t#e ca go #ead 'loc)5 ') Esti%ating t#e Res"ltant Load on t#e Ca go $ead Bloc) The final load on the cargo head block is a result of: the forces e erted by the suspended load, and the stress on the hauling part of the cargo runner#tackle. In the figure, the Hparallelogram of forces% ,B*- is resolved using the scaled values of the load ,B 4@ tonnes in this case5 and the calculated stress on the hauling part ,- 4; tonnes as determined by the formula5. The resultant force at H,% represented by the scaled value of ,*, is the resultant load on the cargo head block 4equals E.= tonnes in this e ample5. c) Esti%ating t#e Tension in t#e Topping Lift ,pan The tension in the topping lift span results from the combined effects of: weight of the load being lifted

ALAM/July 2002

Page 2'

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

The resultant load on the heel block is represented by the scaled value of OP. f) Esti%ating t#e Res"ltant Load on t#e Mast $ead ,pan Bloc) The final load on the mast head span block results from: the tension in the topping lift span and the stress on the hauling part of the topping lift towards the dolly winch In the e ample, the tension in the topping lift span is ;.< tonnes 4as determined in para 24c55 whilst the stress on the hauling part of the topping lift towards the dolly winch would be ;.E< tonnes 4allowing for 2#23 of the topping lift tension for friction in the mast head span block5. The forces are resolved using the Hparallelogram of forces% .1/:, where .1 F the scaled valve of tension in the topping liftspan and .: F the scaled value of stress in the hauling part of the topping lift, towards the dolly winch. The resultant load on the mast head span block is represented by the scale value of ./.

Assignment

:lease complete the assignment and return to ,9,. 25 ) plain the advantages and disadvantages of a union purchase in cargo operation. ?5 , derrick ?< m long is supported by a span 2? m long. ,ttached to a point on the mast ?3 m vertically above the heel of the derrick a guntackle is rove to disadvantage is used to lift a weight of 23 tonnes. 7pan tackle also a guntackle is rove to disadvantage. The mass of the boom is ? tonnes and the mass of cargo gear is 3.@ tonnes. &ind the stress on: i5 -errick head purchase block shackle. ii5 -errick heel block shackle iii5 The load on the mast head span block shackle iv5 The thrust on the derrick 4,fter leaving the heel block runner makes an angle of >33 with mast5

ALAM/July 2002

Page 30

Malaysian Maritime Academy

Correspondence Course

Cargowork

MODULE < - ROLL O.2ROLL OFF SYSTEMS