Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Nardi The Conservation of The Atrium of - Luca Isabella PDF

Încărcat de

postiraTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Nardi The Conservation of The Atrium of - Luca Isabella PDF

Încărcat de

postiraDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The conservation of the Atrium of the Capitoline museum Roberto Nardi Centro di Conservazione Archeologica

1. Introduction This paper presents the conservation programme of the Atrium of the Capitoline Museum in Rome and of the collection of classical sculptures housed in the ground floor. The Palace was built according to plans by Michelangelo in travertine and plastered bricks in 1655. Since 1733 the Atrium houses a collection of 27 roman sculptures: for more than three centuries the statues, gathered together as we see them today, were admired by, and transmitted their cultural, aesthetic and historical message to researchers, artists, ordinary people and travellers passing through Rome. And many of these people have spoken and written about them, or drawn them. The sculpture has become an integral part of the architecture: there is no longer a separation between the statues and the building, between the museum and its collection. It has all fused into a single, unique monument. And for more than three centuries, atmospheric agents, birds, poor maintenance and, finally, the violent aggression of the polluted atmosphere have had an impact on the stone surfaces, which were in a sorry state of decay and almost totally illegible. In 1990, the Superintendency of the City of Rome began a conservation programme for both the sculptures and the building structures, and decided to assign the project to a single team of conservators[1]. For a change, not only the contents of a museum, but also the container itself were being treated. The work was done by the Centro di Conservazione Archeologica of Rome (CCA) that with a team of 10 conservators carried out the project in two years. 2. Information The conservation treatment of the atrium of the Capitoline Museum provided a unique opportunity to launch a campaign of information and cultural promotion. The magnitude of the restoration operation and its great importance on the historical level, combined with the position of the worksite right at the entry of one of the busiest museums of Rome, induced us to start a series of activities to raise public awareness. We wanted to explain the work in progress while also enhancing appreciation of the museum's cultural heritage. Given these premises, the innovative choice of this project was to open the restoration worksite to the public. In this way, the worksite itself would become a stimulus for relationship between the public and the work of art, while also being a vehicle for understanding the various cultural methodologies and techniques of the restoration phases. A painting (7 m high)(See fig.1) depicting the closed-off portico of the atrium was mounted at the entry to the museum and furnished with peepholes. What appeared to be the barrier of the worksite was thus transformed into an instrument to pique the visitor's curiosity and set up a channel of communication between the restorers and the public: with an open worksite, everyone could follow the work in progress; guided visits in various languages brought the public closer to the project and to conservation issues; the availability of didactic material and the operators' readiness for dialogue promoted informal and effective communication. 3. Planning The quantity and quality of the technical operations necessary to implement the project, and the decision to carry out the work in public view called for a great deal of preliminary programming and planning. The idea was to arrive at the opening day of the worksite with nothing left to chance and every detail in place. During this phase, every single technical operation was planned; new equipment was designed and constructed for the special requirements of the project; a system for communicating with the museum direction was defined, as well as systems for study and documentation; the conservators were given a technical refresher course and prepared for communication with the public. The sequence of activities assigned to each operator was recorded with computer management software[2]. This allowed us to study

the details of the calendar, avoid overlapping or dead times, anticipate peak situations and produce informative updates on the progress of the works. Plants for electricity, compressed air and water were installed outside the museum and piped inside under the floor; numerous outlets were supplied to avoid annoying and dangerous tangles of tubes. Each scaffold[3] had its own atomized water plant, shields, drains and outlets for electricity, compressed air and water, so that each one was a mobile, independent work station. Moreover, detailed planning of the treatment makes it possible to plan precisely the extent of each operation and to identify what can be postponed to future maintenance, so that today's treatment can be based on the criterion of minimum intervention. We wanted to focus first on planning the work in order to minimize the impact of the restoration on the monument and limit interference with the life of a museum open to the public. 4. Documentation The work began officially with the analysis of the sculptures. During this phase, information was collected to support the restoration treatment and study of the pieces. The materials and techniques used in old restorations are classified[4] from the marble[5] and mixes used to fill gaps to the resins and oils used for surface treatment, as well as the metals used in the pins. The former additions to replace missing parts in statues were examined closely to identify pieces of recycled ancient marble, such as an epigraph found in the base of the lion. The lime-based treatments, with or without pigment, used on the travertine structures are studied. The colors of the plasters on the walls, which began as light blue and then became green, red, yellow, are detected. The traces of polychromy on the statues, such as the red, yellow, gold, blue, green and violet identified on the Faustina [6], are checked. In this same phase, the stability of the pieces is controlled and operations of preconsolidation are implemented. All information is documented and recorded, ready to be extracted and compared for the global study of the collection and for publication of the entire project.[7] 5. Cleaning Treatment of the marble and travertine surfaces began with cleaning. This was carried out with atomized water, produced by machinery that can mix air and water at low pressure in proportions that in the most delicate cases (such as the sculpture) are as light as one part water to 400 air. The surfaces were subjected to the subtle action of an aerosol that can dissolve the deposits of dirt, even when they are in the form of thick black crusts. No mechanical meens or abrasion were used on the surfaces: the dirt deposits softened, but not removed, by the aerosol were brushed off with a paint or scrub brush. Thus, the cleaning was not an automatic operation, but constantly under the conservator's control. In the case of insoluble deposits we resorted to mechanical cleaning with scalpels, chisels or light air hammers. The presence of treatments residues from old restorations patinas, resins, stains required case by case decisions : the basic principle adopted was that some of the old restorations could be kept as document and history, but all those presenting unstable situations or disturbing the "legibility" of the entire sculpture had to be documented and removed. This required some cleaning with chemical agents (water and ammonia, gently heated with warm air to facilitate the extraction) in poultices that could dissolve, extract and remove such materials. Careful rinsing combined with poultices of distilled water and absorbent pulp to extract soluble salts conclude the cleaning process. The presence of the numerous metallic parts used in restoring the sculpture made it necessary either to treat them or to remove and replace them with stable materials. For the first operation, we used stabilizing agents for iron oxide (rust), based on tannic acid, over which a double layer of epoxy and polyurethane paints was applied.[8] For replacement, fiberglass pin were used. The marble parts which were detached during these operations are then put back into position with epoxy resin applied on a reversible film of acrylic resin.[9] 6. Pre-consolidation, consolidation, stuccoing The criterion guiding the conservation programme for the atrium of the Capitoline Museum was that of exploiting modern technology to the maximum during the planning, studying and documenting stages while respecting history and tradition in the choice of techniques and materials for the treatment of

surfaces stage. Study of surfaces and stratigraphy and archive research were not only a useful exercise for understanding the original building practice, but were also a preparatory tool for choosing the techniques and materials to be used in the conservation treatments of today. A monument is not only the image it projects, but also the material of which it is made and the result of the techniques with which it was built and maintained. This is why we wanted to ensure that the modern techniques and materials we used were compatible with the monument from the standpoint of material and history as well as aesthetics. A prime example of this approach was the choice of lime as the basic material for consolidation, stuccoing and surface protection. For some years now, lime has regained the leading role it deserves and has replaced highly damaging cement and overworked synthetic products. Lime can be used for a variety of purposes, depending on how much it is diluted and the powders with which it is mixed in mortars: these range from preconsolidation, stuccoing and integration to final protection. The use of lime respects the monument's history because, except for the most recent decades, it was built, restored and maintained with lime-based techniques. Lime water was used for preconsolidation of decayed marble (obtained by mixing 1 gram of slaked lime in 1 liter of water). It is applied with a syringe or paint brush. By increasing the lime content, we obtain a creamy product that can be painted on travertine for consolidation. To stucco cracks or lacunae on marble and travertine, a base layer of "cocciopisto" is applied a conglomerate of slaked lime, pozzolana and brick fragments in a proportion of 1 to 3 as indicated even by ancient sources. This mixture, thanks to its ability to absorb contractions of the material as it dries, serves to fill in areas of large dimensions and to prepare a base layer for final stuccoing. For the stuccoing we used mortars based on slaked lime, sand and colored marble dust, again in a proportion of 1 to 3, with loads that can vary according to the color desired. Finally, a liquid mortar composed of slaked lime, water, travertine powder and colored earths, was applied as a final coating to protect travertine surfaces. Unlike synthetic products, which appear to give positive results at the moment of application under any conditions but which then reveal their defects as time goes by, lime offers guaranteed, predictable results in the long run, but certain precise rules must be followed. Otherwise, the operation will fail totally. We hardly need mention that if the knowledge of a trade and its rules is vital in any field, it is even more vital in that of conservation of cultural heritage. These rules include the application method and the environmental conditions under which it is carried out. The climate should not be too hot and dry for example, in Rome one should not work directly in the sun in July and August. The surfaces must first be thoroughly wetted. The final stucco must be pressed and polished several times with brushes the "politones" mentioned by Vitruvius[10] until it is completely hardened. Protective coatings on travertine must be applied with a palette knife or better, with a sponge and massaged on wet surfaces; once dry, they are finished by brushing away the excess powdery material. 7. Rendering Lime was also the binder for the paint used for the wall plasters where, with the addition of natural blue and black pigments, we returned to the light-blue color found in the cross-sections and archival sources. Furthermore, with the addition of raw umber it was used to reconstruct the fake travertine surfaces of the plaster ribs of the ceiling of the stairway. When mixed with brick dust, it was applied in a wash with fresco technique for the back wall of the gallery, once made of brick. These and other treatments of the architecture were an integral part of the intervention, which attempted to recover the play of materials and techniques that had been cleverly used by the designer in conceiving the harmony of the architectural setting. With the help of historical and stratigraphic information, we attempted to reconstruct the original architectural organization, which had been lost over the centuries. We re-proposed the play of form and space, the contrast between the power of the travertine structures and the lightness of the sky-blue walls and vaults. It was in such a light and luminous environment that the collection was displayed to the public for the first time. 8. Questionnaire A significant confirmation of the validity of the initiatives organized to inform the public was obtained through a questionnaire distributed to visitors in front of a statue that was deliberately not restored. For a week, the public was asked to respond to various questions on the theme of protection of cultural heritage.

The questions changed every day, and the responses were posted daily in the museum. The responses about maintenance were particularly interesting, and demonstrated a high level of maturity and awareness of heritage protection and good management of public property. People no longer believe in spectacular projects, in eternal treatments, in operations that transform instead of conserving the monument. Nowadays, they expect treatments to be minimal but regular no more extraordinary restorations, but ordinary maintenance. And this is what was accomplished in the course of the conservation treatment of the atrium of the Capitoline Museum. (See figs. 2 - 6) 9. Maintenance Maintenance is the natural extension of the conservation treatments that have just been completed: without this the results obtained during the treatment are quickly nullified. For this reason, the conservation of the Atrium of the Capitoline Museum has been planned as a preparation for future maintenance and the maintenance is seen as a measure to prevent future deterioration. This means: minimal use of materials and treatments, made it possible by the option to return in the future; use of lime-based techniques, that means that the monument is modified as little as possible because the materials used are compatible with the originals; use of a computerized documentation technique that allows continuous updating. The maintenance is organized on a three times a year base. The actual contract is for five years: after this period the results will be analized and a new, definitive, long term programme will be set. The technical operations carried out are: preparation (treatments, worksite, tools, materials) cleaning (removing deposits of atmospheric particulates, by vacuum-cleaner and light brushing; reviewing (assessing the stucco, and replacing deteriorated areas; checking the response of marble surfaces to particulate deposits, with possible localized application of protective coatings; checking repairs and metal elements; verifying the stability of old restorations; checking for possible cracks and colour changes; verifying whether salts are present); varia (scaffolding movement, information of the public, contingencies); documentation (analysis and report). All information collected and every operation carried out is recorded on computer charts, adding to the data already entered in the course of the recent treatment. Comparison between the existing material and the actual information will provide the elements necessary for detailed study of how deterioration of the monument proceeds. The time required to performe the above activities is constantly recorded during the work. (See fig. 7). The total time for the entire collection of sculptures is 40 hours, plus 24 hours for travertine. This means about 2 working days, 4 conservators, plus the time for transportation, organization and clearing the working area. The cost for the maintenance of sculptures and structures in travertine is of US$7,500 a year, including expenses for materials, equipment, transport and documentation. 10 Conclusions At the end of this paper it seems useful to list the principles behind the conservation of the Atrium of the Capitoline Museum (besides, that is, the material result of the conservation of the sculptures and of the structures). - The project dealt with an historical palace and with the collection housed in it since three hundred years: only one programme for container and content. The museum is finally considered and appreciated as a single monument. No more divisionS between intervention on the structures (with one team) and treatment of the sculptures (with an other team). This kind of divisions produced in the past interferences and wasting energies that affected the cultural quality of the programmes. - All the operative indications such as the choice of techniques and materials followed the historical investigation carried out in archive and on site. This way we wanted to achieve maximum compatibility with history, tradition, techniques and materials as well as the aesthetics of the monument. - The programme of conservation included initiatives to inform the public. The work was entirely carried out in public view and direct contact between visitors and conservators was stimulated. Conservation

work,which is often guilty of blocking visitor's access to monuments, produced this time extra information to people. An operation traditionally considered merely techniques, evolved into a cultural programme at the service of the public. - The restoration is finished, but the conservation programme doesn't end here: it continues with a maintenance plan to guarantee that the results obtained will not be lost. This principle has been accepted and the operations are now carried out every three months: maintenance, neglected for years, is finally back as part of the every- day history of the monument.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to acknowledge the Istituto Centrale del Restauro of Rome for the analyses of the traces of polychromy on the statues and the British Museum for the analyses of the marble.

AUTHOR Roberto Nardi took a degree in archaeology at the University of Rome and a certificate in conservation at the Istituto Centrale del Restauro. Since 1982 he is director of the Centro di Conservazione Archeologica (CCA), a private company undertaking public commitments in conservation of ancient monuments and archaeological sites. He has been in charge of some conservation projects, including the Arch of Septimius Severus and the Temple of Vespasian in the Roman Forum, the Crypta Balbi, the Stadium of Domitian, the Atrium of the Capitoline Museum. He actually in charge of a three-years project in Masada, Israel. He is an associate professor at ICCROM. Address: 19 Via del Gambero, 00187 Rome, Italy.

Activity Preparation Cleaning Reviewing Varia Documentation TOTAL

Time in minutes 20 min. 40 min. 15 min. 10 min. 20 min. 1,25 hour

CAPTIONS Fig. 1 The painting 7 meters high depicting the closed off portico of the Atrium was also used as logo of the project. (The drawing was made by Andreina Costanzi Cobau) Fig. 2-6 The results of the questionnaires distributed to the public. The results have been elaborated on 750 answers. Fig. 7 Activities and time required to carry out the maintenance of the sculptures. Time is elaborated on an average of 27 sculptures after one year of treatment. Photo 1. General view of the Atrium. (Araldo De Luca) Photo 2. Mars (Araldo De Luca) Photo 3. A detail of Hadrian (Araldo De Luca) Photo 4. The delegates of the General Assembly of ICCROM visited the worksite in 1993

NOTES

1.The work was directed by Drs Marina Mattei, Anna Sommella and Elisa Tittoni of the Xth Section of the Sovraintendenza del Comune di Roma, for the Sovraintendente, Prof. Eugenio La Rocca. 2.Microsoft Project, Microsoft Corporation (1991). 3.Instant Italia, Via Montanari 5, 27028 San Martino Siccomario (PV), Italy. The scaffolding used in this project is the model "scala". 4.Peter Rockwell and Gianni Ponti carried out the investigation of the original carving techniques 5.British Museum, Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Dr. Susan Walker 6.Istituto Centrale del Restauro, Department of Chemistry, Dott. Costantino Meucci and Ulderico Santamaria 7.Autocad, Autodesk 8.Lecher Vernici, Centro vernici, Via Visconte Maggiolo, 2, Roma. Linea "Epofan" 9.Uhu Plus, Beecham Italia, Milano, Italy Paraloid B72, (Acriloid), Room and Haas, Angler Filital, Via della Filanda, Gessate, Milan, Italy 10.Vitruvio, De architettura, VII, 3.3

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Digital Mosaic Frameworks - An Overview: ForumDocument19 paginiDigital Mosaic Frameworks - An Overview: ForumpostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- 472765.TILURIJ 32-111 STRDocument40 pagini472765.TILURIJ 32-111 STRpostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- A Survey of Digital Mosaic TechniquesDocument7 paginiA Survey of Digital Mosaic TechniquespostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kelt Is Vast IkeDocument8 paginiKelt Is Vast IkepostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Wootton MosaicsDocument12 paginiWootton MosaicspostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Blazenka HIJERARHIJAishoda UCENJADocument29 paginiBlazenka HIJERARHIJAishoda UCENJApostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- ICCROM Newsletter 28 - ICCROM PDFDocument0 paginiICCROM Newsletter 28 - ICCROM PDFpostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- ICCROM - Newsletter 30 - ICCROM PDFDocument0 paginiICCROM - Newsletter 30 - ICCROM PDFpostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- ICCROM - Newsletter 32 - ICCROM PDFDocument32 paginiICCROM - Newsletter 32 - ICCROM PDFpostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Newsletter 34 - ICCROM PDFDocument0 paginiNewsletter 34 - ICCROM PDFpostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Cassio-Nardi-Schneider Mosaics Restorati - Luca Isabella PDFDocument7 paginiCassio-Nardi-Schneider Mosaics Restorati - Luca Isabella PDFpostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Conservation and Maintenance of Floor Mo - Luca Isabella PDFDocument13 paginiConservation and Maintenance of Floor Mo - Luca Isabella PDFpostiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Bizet - Farandole ScoreDocument16 paginiBizet - Farandole ScoreBlackStar_Încă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Dhikr and Prayers After The Tahajud SalahDocument5 paginiDhikr and Prayers After The Tahajud Salahselaras coidÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1998 Art of AccidentDocument230 pagini1998 Art of AccidentRiccardo Mantelli100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Musical Instruments of IndonesiaDocument3 paginiMusical Instruments of IndonesiaAimee HernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amazing Bella by Crochet GarageDocument20 paginiAmazing Bella by Crochet GarageKADIKIZI100% (5)

- B Ing PronounsDocument4 paginiB Ing PronounsSilvia Surya NingrumÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Curtain Wall Installation Instructions - Rev 05-04-11Document36 paginiCurtain Wall Installation Instructions - Rev 05-04-11rmdarisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Create Striking PortraitsDocument6 paginiCreate Striking PortraitsDurgesh Sirwani100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- TravelCLICK Premium Consortia Directory PDFDocument31 paginiTravelCLICK Premium Consortia Directory PDFquentinejamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homily For Epiphany 2 Year B 2009Document4 paginiHomily For Epiphany 2 Year B 2009api-3806971Încă nu există evaluări

- HD - 350 RS Monthly: Genre Channel Name Channel NoDocument2 paginiHD - 350 RS Monthly: Genre Channel Name Channel NoAksh SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

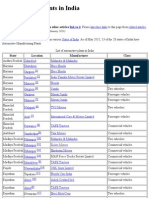

- List of Vehicle Plants in India - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 paginiList of Vehicle Plants in India - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAjay Marya50% (2)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Egyptian Gods & Mythology - Hollywood SubliminalsDocument10 paginiEgyptian Gods & Mythology - Hollywood SubliminalsVen GeanciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 16IdiomsAnimals (CAE&CPE)Document9 pagini16IdiomsAnimals (CAE&CPE)Denise MartinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beautiful Kitchens Magazine JulyAugust 2014 PDFDocument109 paginiBeautiful Kitchens Magazine JulyAugust 2014 PDFrhodzsulit100% (2)

- Harris Broadcasting Accessories 1982Document200 paginiHarris Broadcasting Accessories 1982João Pedro AlmeidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- WP 5020Document2 paginiWP 5020Mark CheneyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Where Riches Is Everlastingly - WarlockDocument1 paginăWhere Riches Is Everlastingly - WarlockPaulo RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crime Scene PhotographyDocument37 paginiCrime Scene PhotographyMelcon S. Lapina50% (2)

- Toomer, John Selden (Review)Document2 paginiToomer, John Selden (Review)Ariel HessayonÎncă nu există evaluări

- द्वेषो मोक्षश्च - Hatred and Moksha: BhaktiDocument13 paginiद्वेषो मोक्षश्च - Hatred and Moksha: BhaktiJankee LackcharajÎncă nu există evaluări

- DJ Naves BioDocument1 paginăDJ Naves BioTim Mwita JustinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adeena Islamiyat Assignment 2 (Companion)Document10 paginiAdeena Islamiyat Assignment 2 (Companion)AdeenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14 PatolliDocument8 pagini14 PatolliCaroline Martins Nacari100% (1)

- Datasheet of DS-2DE5225IW-AE (C)Document6 paginiDatasheet of DS-2DE5225IW-AE (C)nvnakumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sad I Ams Module Lit Form IDocument38 paginiSad I Ams Module Lit Form ImaripanlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- American History XDocument110 paginiAmerican History XNick LaurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Its Kind of A Funny StoryDocument115 paginiIts Kind of A Funny Storyspider.chinna20078777Încă nu există evaluări

- What Are The Elements of A BiographyDocument3 paginiWhat Are The Elements of A BiographyEstelle Nica Marie Dunlao100% (2)

- The Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan (PDFDrive)Document96 paginiThe Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan (PDFDrive)Adeniyi Adedolapo OLanrewajuÎncă nu există evaluări