Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Pub Corp Notes

Încărcat de

Sherine Lagmay RivadTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Pub Corp Notes

Încărcat de

Sherine Lagmay RivadDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

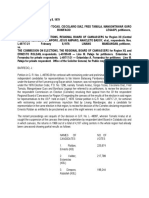

1987 Philippine Constitution, Article X LGC Territorial and political subdivisions of the Republic of the Philippines -> enjoy

oy local autonomy Provinces, cities, municipalities, and barangays Autonomous regions in: o Muslim Mindanao and o Cordilleras -> not existing to date Enactment of LGC by Congress; Purpose: More responsive and accountable local government structure instituted through a system of decentralization -> recall, initiative, referendum Allocate among the different local government units their powers, responsibilities, and resources Provide for the qualifications, election, appointment and removal, term, salaries, powers and functions and duties of local officials All other matters relating to the organization and operation of the local units President -> general supervision over local governments Provinces -> Component cities and municipalities Cities and Municipalities -> Barangays Ensure that the acts of their component units are within the scope of their prescribed powers and functions Power of LGUs: To create its own sources of revenues To levy taxes, fees and charges subject to such guidelines and limitations as the Congress may provide -> accrue exclusively to LGU Just share, as determined by law, in the national taxes which shall be automatically released to them -> IRA Equitable share in the proceeds of the utilization and development of the national wealth within their respective areas Term of Office of Elective Officials: 3 years not more than 3 consecutive terms XPN: Barangay Officials -> 5 years (RA 8524) Voluntary renunciation -> not interrupt period of term Legislative bodies of LGU -> sectoral representation Creation, Division, Merger, Abolishment of LGU: Approval by a majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite in the political units directly affected (see notes in LGC) Congress may create special metropolitan political subdivisions -> subject to a plebiscite Component cities and municipalities -> retain their basic autonomy and shall be entitled to their own local executive and legislative assemblies Jurisdiction of the metropolitan authority -> limited to basic services requiring coordination Independent Component Cities -> highly urbanized cities whose charters prohibit their voters from voting for provincial elective officials LGUs may group themselves, consolidate or coordinate their efforts, services, and resources for purposes commonly beneficial to them in accordance with law President to provide for regional development councils or other similar bodies composed of local government officials, regional heads of departments and other government offices, and representatives from nongovernmental organizations within the regions Purpose: Administrative decentralization to strengthen the autonomy of the units therein and to accelerate the economic and social growth and development of the units in the region

All powers, functions, and responsibilities not granted by Constitution or by law to the autonomous regions -> vested in the National Government Congress to enact Organic Act with assistance and participation of: regional consultative commission composed of representatives appointed by the President from a list of nominees from multi-sectoral bodies. Purpose of Organic Act: Defines the basic structure of government for the region consisting of the executive department and legislative assembly Provide for special courts with personal, family, and property law jurisdiction consistent with the provisions of this Constitution and national laws Organic act shall provide for legislative powers over: Subject to Constitution and National Laws Administrative organization; Creation of sources of revenues; Ancestral domain and natural resources; Personal, family, and property relations; Regional urban and rural planning development; Economic, social, and tourism development; Educational policies; Preservation and development of the cultural heritage; and Such other matters as may be authorized by law for the promotion of the general welfare of the people of the region. Preservation of peace and order within the regions shall be the responsibility of the local police agencies which shall be organized, maintained, supervised, and utilized in accordance with applicable laws. The defense and security of the regions shall be the responsibility of the National Government.

REYNALDO R. SAN JUAN vs. CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION (CSC): 1987 Consti -> Sec 25 Art II provides that The State shall ensure the autonomy of local governments o This is further bolstered by the 14 Sections under Art X which give in greater detail the provisions making local autonomy more meaningful o Respondent: The right given by Local Budget Circular No. 31 Section 6, stating that the DBM reserves the right to fill up any existing vacancy where none of the nominees of the local chief executive meet the prescribed requirements o SC: Nomination and appointment process involves a sharing of power between the two levels of government -> Provincial and municipal budgets are prepared at the local level and after completion are forwarded to the national officials for review. DATU FIRDAUSI I.Y. ABBAS et al vs. COMELEC; ATTY. ABDULLAH D. MAMA-O vs. HON. GUILLERMO CARAGUE: The creation of the autonomous regions is not absolute, but conditional to the results of the plebiscite therefor. Under the Constitution and R.A. No 6734, the creation of the autonomous region shall take effect only when approved by a majority of the votes cast by the constituent units in a plebiscite, and only those provinces and cities where a majority vote in favor of the Organic Act shall be included in the autonomous region. The provinces and cities wherein such a majority is not attained shall not be included in the autonomous region. It may be that even if an autonomous region is created, not all of the thirteen (13) provinces and nine (9) cities mentioned in Article II, section 1 (2) of R.A. No. 6734 shall be included therein. The single plebiscite contemplated by the Constitution and R.A. No. 6734 will therefore be determinative of (1) whether there shall be an autonomous region in Muslim Mindanao and (2) which provinces and cities, among those enumerated in R.A. No. 6734, shall compromise it. (read Art. X, sec. 18 in relation to Article XVIII, section 27) o The contention that those sharing the same cultural heritage should only be the ones includes is likewise untenable because to rule otherwise would tantamount to violation of the separation of powers since the same is within the exclusive realm of the legislature's discretion. o As to the position that the law violates the equal protection clause, it is settled that this constitutional guarantee permits reasonable classification, as in the instant case where classification was done by Congress based on substantial distinctions as set forth by the Constitution itself

Autonomous Regions Creation of Muslim Mindanao and Cordilleras -> consists of provinces, cities, municipalities, and geographical areas -> sharing common and distinctive historical and cultural heritage, economic and social structures, and other relevant characteristics within the framework of this Constitution and the national sovereignty as well as territorial integrity Creation: Approved by majority of the votes cast by the constituent units in a plebiscite called for the purpose, Only provinces, cities, and geographic areas voting favorably in such plebiscite shall be included in the autonomous region President -> general supervision over autonomous regions to ensure compliance in laws

Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

As to the contention that the law violates religious freedom, no controversy to such effect existed between the real litigants, hence, this issue cannot be decided by the Court in the present case. Petitioners argument that the law gives undue power to the President in that the latter is allowed to merge the existing regions by administrative determination if the plebiscites results were otherwise, this provision being contrary to Article X Sec 10 of the 1987 Consti which provides that only upon approval by majority votes cast in a plebiscite in the political units directly affected, is likewise UNTENABLE. This is because the constitutional provision mentioned only relates to the a province, city, municipality, or barangay being created, divided, merged, abolished, or its boundary substantially altered and NOT to the merger of existing regions. Lastly, Petitioners argument that the creation of an Oversight Committee to supervise the transfer of powers of the regions shall unduly delay the creation of the autonomous region likewise does not hold water because such creation hinges only on the result of the plebiscite and, if the latter is favorable, the same shall have immediate effect.

Types of autonomy:

the central government delegates administrative powers to political subdivisions in order to broaden the base of government power and in the process to make local governments "more responsive and accountable and ensure their fullest development as self-reliant communities and make them more effective partners in the pursuit of national development and social progress

decentralization of administration

SULTAN ALIMBUSAR P. LIMBONA vs. CONTE MANGELIN et al: ISSUE: Whether the autonomy of the SanggunianPampook placed it outside the jurisdiction of the national government, i.e., the national courts. HELD: No o Autonomous regions in Regions IX and XII were created by virtue of Presidential Decree No. 1618 which established "internal autonomy" in the two regions "[w]ithin the framework of the national sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of the Philippines and its Constitution," with legislative and executive machinery to exercise the powers and responsibilities specified therein o The regions were required to "undertake all internal administrative matters for the respective regions," except to "act on matters which are within the jurisdiction and competence of the National Government," o However, the question on whether the autonomy contemplated in the instant case involves decentralization of administration or of power should be decided by the Court in a proper case involving the proper issue. o Under Article X 1987 Consti, LGUs enjoy autonomy in 2 senses, to wit: Constitutional Provisions (under Article X) Sec 1. The territorial and political subdivisions of the Republic of the Philippines are the provinces, cities, municipalities, and barangays. There shall be autonomous regions in Muslim Mindanao ,and the Cordilleras as hereinafter provided. Sec 2. The territorial and political subdivisions shall enjoy local autonomy. Sec 15. There shall be created autonomous regions in Muslim Mindanao and in the Cordilleras consisting of provinces, cities, municipalities, and geographical areas sharing common and distinctive historical and cultural heritage, economic and social structures, and other relevant characteristics within the framework of this Constitution and the national sovereignty as well as territorial integrity of the Republic of the Philippines.

relieves the central government of the burden of managing local affairs and enables it to concentrate on national concerns

President exercises "general supervision" over them, but only to "ensure that local affairs are administered according to law."

President has no control over their acts in the sense that he can substitute their judgments with his own

involves an abdication of political power in the favor of local governments units declare to be autonomous

Distinctions decentralization of power

the autonomous government is free to chart its own destiny and shape its future with minimum intervention from central authorities

under the supervision of the national government acting through the President (and the Department of Local Government) hence unarguably under the Court's jurisdiction o

amounts to "self-immolation," since in that event, the autonomous government becomes accountable not to the central authorities but to its constituency

subject alone to the decree of the organic act creating it and accepted principles on the effects and limits of "autonomy" hence beyond the domain of this Court in perhaps the same way that the internal acts, say, of the Congress of the Philippines are beyond our jurisdiction

PD 1618 mandates that "[t]he President shall have the power of general supervision and control over Autonomous Regions." And provides that the SangguniangPampook, their legislative arm, is made to discharge chiefly administrative services o Hence, the law never meant to have the LGUs in the instant case exercise autonomy tantamount to the central governments act of self-immolation o Ergo, the Court may verily look into the expulsion of Petitioner The Court sustained Petitioners position that the proceedings were null and void because the Assembly was then on recess o Under Section 31 of the Region XII Sanggunian Rules, "[s]essions shall not be suspended or adjourned except by direction of the SangguniangPampook," but it provides likewise that "the Speaker may, on [sic] his discretion, declare a recess of "short intervals. o Respondents posited that the phrase recess of short intervals pertains to those that happen whenever arguments get heated up for the purpose of letting the parties settle their arguments, and not the recess contemplated by Petitioner 2

Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

The Court opined that, while Respondents were correct in said position, such cannot be applied in the instant case because the phrases meaning has not been clarified yet during the time that Petitioner called for such recess and that it was not made aware by Respondents to Petitioner that such calling of recess was not permitted Hence, the Court upheld the "recess" called on the ground of good faith

Cordillera Regional Assembly Member ALEXANDER P. ORDILLO et al vs. The COMELEC (COMELEC) et al

Issue: Whether or not the province of Ifugao, being the only province which voted favorably for the creation of the Cordillera Autonomous Region can, alone, legally and validly constitute such Region Held: No. o Article X, Section 15 of the 1987 Constitution: o The keywords provinces, cities, municipalities and geographical areas connote that "region" is to be made up of more than one constituent unit. The term "region" used in its ordinary sense means two or more provinces. o Ifugao is a province by itself. To become part of a region, it must join other provinces, cities, municipalities, and geographical areas.

MMDA vs. BEL-AIR VILLAGE ASSOCIATION (BAVA), INC. Issue: Whether or not the mandate to open a private street to public is within MMDAs regulatory and police powers Held: No. o The MMDA is not the same entity as the MMC in Sangalang. Although the MMC is the forerunner of the present MMDA, an examination of Presidential Decree (P. D.) No. 824, the charter of the MMC, shows that the latter possessed greater powers which were not bestowed on the present MMDA. o The administration of Metropolitan Manila, established as a public corporation under the said decree, was placed under the MMC Metropolitan or Metro Manila is a body composed of several local government units i.e., twelve (12) cities and five (5) municipalities o The MMC was the "central government" of Metro Manila for the purpose of establishing and administering programs providing services common to the area. As a "central government" it had: the power to levy and collect taxes and special assessments, the power to charge and collect fees; the power to appropriate money for its operation, and at the same time, review appropriations for the city and municipal units within its jurisdiction o The creation of the MMC also carried with it the creation of the Sangguniang Bayan. o Thus, Metropolitan Manila had a "central government," i.e., the MMC which fully possessed legislative police powers. With the passage of R.A. No. 7924 in 1995, Metropolitan Manila was declared as a "special development and administrative region" and the Administration of "metro-wide" basic services affecting the region placed under "a development authority" referred to as the MMDA. o It will be noted that the powers of the MMDA are limited to the following acts: formulation, coordination, regulation, implementation, preparation, management, monitoring, setting of policies, installation of a system and administration. There is no syllable in R.A. No. 7924 that grants the MMDA police power, let alone legislative power. o The power delegated to the MMDA is that given to the Metro Manila Council, its governing board, to promulgate

administrative rules and regulations in the implementation of the MMDA's functions. o There is no grant of authority to MMDA to enact ordinances and regulations for the general welfare of the inhabitants of the metropolis. MMDA is not a local government unit or a public corporation endowed with legislative power. It is not even a "special metropolitan political subdivision" as contemplated in Section 11, Article X of the Constitution. o The creation of a "special metropolitan political subdivision" requires the approval by a majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite in the political units directly affected." o R. A. No. 7924 was not submitted to the inhabitants of Metro Manila in a plebiscite. MMC under P.D. No. 824 is not the same entity as the MMDA under R.A. No. 7924. o Unlike the MMC, the MMDA has no power to enact ordinances for the welfare of the community. It is the local government units, acting through their respective legislative councils, that possess legislative power and police power. o In the case at bar, the Sangguniang Panlungsod of Makati City did not pass any ordinance or resolution ordering the opening of Neptune Street, hence, its proposed opening by petitioner MMDA is illegal and the respondent Court of Appeals did not err in so ruling. We desist from ruling on the other issues as they are unnecessary. The MMDA was created to put some order in the metropolitan transportation system but unfortunately the powers granted by its charter are limited.

THE LGC OF THE PHILIPPINES (RA No. 7160) BOOK I: GENERAL PROVISIONS TITLE ONE. - BASIC PRINCIPLES CHAPTER 1. - THE CODE: POLICY AND APPLICATION SECTION 1. Title. - This Act shall be known and cited as the "LGC of 1991". SEC. 2. Declaration of Policy. (a) It is hereby declared the policy of the State that: the territorial and political subdivisions of the State shall enjoy genuine and meaningful local autonomy Rationale: to enable them to attain their fullest development as self-reliant communities and make them more effective partners in the attainment of national goals. The State shall provide for a more responsive and accountable local government structure instituted through a system of decentralization from national government to local government units, whereby local government units shall be given more: powers, authority, responsibilities, and resources. (b) To ensure the accountability of local government units through the institution of effective mechanisms of recall, initiative and referendum. (c) To require all national agencies and offices to conduct periodic consultations before any project or program is implemented in their respective jurisdictions with appropriate local government units, non-governmental and people's organizations, and other concerned sectors of the community SEC. 3. Operative Principles of Decentralization. - The formulation and implementation of policies and measures on local autonomy shall be guided by the following operative principles: (a) There shall be an effective allocation among the different local government units of their respective powers, functions, responsibilities, and resources; (b) There shall be established in every local government unit an accountable, efficient, and dynamic organizational structure and operating mechanism that will meet the priority needs and service requirements of its communities;

Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

(c) Subject to civil service law, rules and regulations, local officials and employees paid wholly or mainly from local funds => shall be appointed or removed, according to merit and fitness, by the appropriate appointing authority; (d) The vesting of duty, responsibility, and accountability in local government units shall be accompanied with provision for reasonably adequate resources to discharge their powers and effectively carry out their functions; hence, they shall have: the power to create and broaden their own sources of revenue and the right to a just share in national taxes and an equitable share in the proceeds of the utilization and development of the national wealth within their respective areas; (e) Provinces with respect to component cities and municipalities, and cities and municipalities with respect to component barangays, shall ensure that the acts of their component units are within the scope of their prescribed powers and functions; (f) Local government units may group themselves, consolidate or coordinate their efforts, services, and resources for purposes commonly beneficial to them; (g) The capabilities of local government units,especially the municipalities and barangays, shall be enhanced by providing them with opportunities to participate actively in the implementation of national programs and projects; (h) There shall be a continuing mechanism to enhance local autonomy not only by legislative enabling acts but also by administrative and organizational reforms; (i) Local government units shall share with the national government the responsibility in the management and maintenance of ecological balance within their territorial jurisdiction, subject to the provisions of this Code and national policies; (j) Effective mechanisms for ensuring the accountability of local government units to their respective constituents shall be strengthened in order to upgrade continually the quality of local leadership; (k) The realization of local autonomy facilitated through improved coordination of national government policies and programs and extension of adequate technical and material assistance to less developed and deserving local government units; (l) The participation of the private sector in local governance, particularly in the delivery of basic services, shall be encouraged Purpose: to ensure the viability of local autonomy as an alternative strategy for sustainabledevelopment; and (m) The national government shall ensure that decentralization contributes to the continuing improvement of the performance of local government units and the quality of community life.

(e)In the resolution of controversies arising under this Code where no legal provision or jurisprudence applies => resort may be had to the customs and traditions in the place where the controversies take place.

CHAPTER 2. - GENERAL POWERS AND ATTRIBUTES OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNITS SEC. 6. Authority to Create Local Government Units. - A local government unit may be created, divided, merged, abolished, or its boundaries substantially altered either by law enacted by Congress => in the case of a province, city, municipality, or any other political subdivision, or by ordinance passed by the sangguniang panlalawigan or sangguniang panlungsod concerned => in the case of a barangay located within its territorial jurisdiction, subject to such limitations and requirements prescribed in this Code. SEC. 7. Creation and Conversion. GR: the creation of a local government unit or its conversion from one level to another level shall be based on verifiable indicators of viability and projected capacity to provide services, to wit: (a) Income. It must be sufficient, based on acceptable standards, to provide for all essential government facilities and services and special functions commensurate with the size of its population, as expected of the local government unit concerned; (b) Population. - It shall be determined as the total number of inhabitants within the territorial jurisdiction of the local government unit concerned; and (c) Land Area. It must be contiguous. XPN: Comprises two or more islands or is separated by a local government unit independent of the others; properly identified by metes and bounds with technical descriptions; and sufficient to provide for such basic services and facilities to meet the requirements of its populace. Compliance with the foregoing indicators shall be attested to by the: Department of Finance (DOF), the NationalStatistics Office (NSO), and the Lands Management Bureau(LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources(DENR) Income At least P2.5M (average annual for the last 2 consecutive years) Population At least 25,000 Land Area At least 50 sq. Km.

LGU Municipality

SEC. 4. Scope of Application. - This Code shall apply to all provinces, cities, municipalities, barangays, and other political subdivisions as may be created by law, and, to the extent herein provided, to officials, offices, or agencies of the national government SEC. 5. Rules of Interpretation. - In the interpretation of the provisions of this Code, the following rules shall apply (a)Any provision on a power of a local government unit => liberally interpreted in its favor In case of doubt: any question thereon => in favor of devolution of powers and of the lower local government unit. Any fair and reasonable doubt as to the existence of the power => in favor of the local government unit concerned; (b) In case of doubt, any tax ordinance or revenue measure => construed strictly against the local government unit enacting it, and liberally in favor of the taxpayer. Any tax exemption, incentive or relief granted by any local government unit pursuant to the provisions of this Code => construed strictly against the person claiming it. (c) The general welfare provisions in this Code =>liberally interpreted to give more powers to local government units in accelerating economic development and upgrading the quality of life for the people in the community; (d) Rights and obligations existing on the date of effectivity of this Code and arising out of contracts or any other source of prestation involving a local government unit shall be governed by the original terms and conditions of said contracts or the law in force at the time such rights were vested; and

Barangay

At least 5,000 for Metro Manila and other highly urbanized cities

Otherwise, at least 2,000

Component City

At least P20M (average annual for the last 2 consecutive years) Sec. 450, LGC

At least 150,000

At least 100 sq. km

For highly urbanized city: At least P50M For Highly urbanized city: At 4

Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

least 200,000

Province

At least P20M

At least 250,000

At least 2,000 sq. Km.

SEC. 8. Division and Merger. - Division and merger of existing local government units shall comply with the same requirements herein prescribed for their creation: Provided, however, That such division shall not reduce the income, population, or land area of the local government unit or units concerned to less than the minimum requirements prescribed in this Code: Provided, further, That the income classification of the original local government unit or units shall not fall below its current income classification prior to such division. The income classification of local government units shall be updated within six (6) months from the effectivity of this Code to reflect the changes in their financial position resulting from the increased revenues as provided herein.

SEC. 12. Government Centers. - Provinces, cities, and municipalities shall endeavor to establish a government center where offices, agencies, or branches of the national government , local government units, or government-owned or -controlled corporations may, as far as practicable, be located. In designating such a center, the local government unit concerned shall => take into account the existing facilities of national and local agencies and offices which may serve as the government center as contemplated under this Section. The national government , local government unit or governmentowned or -controlled corporation concerned shall=> bear the expenses for the construction of its buildings and facilities in the government center SEC. 13. Naming of Local Government Units and Public Places, Streets and Structures (a) The sangguniang panlalawigan may, in consultation with the Philippine Historical Commission (PHC), change the name of the following within its territorial jurisdiction: Component cities and municipalities => upon the recommendation of the sanggunian concerned; Provincial roads, avenues, boulevards, thorough-fares, and bridges; Public vocational or technical schools and other post-secondary and tertiary schools; Provincial hospitals, health centers, and other health facilities; and Any other public place or building owned by the provincial government (b) The sanggunian of highly urbanized cities and of component cities whose charters prohibit their voters from voting for provincial elective officials, i.e. independent component cities, may, in consultation with the Philippine Historical Commission, change the name of the following within its territorial jurisdiction City barangay => upon the recommendation of the sangguniang barangay concerned; City roads, avenues, boulevards, thoroughfares,and bridges Public elementary, secondary and vocational or technical schools, community colleges and non-chartered colleges; City hospitals, health centers and other health facilities; and (5) Any other public place or building owned by thecity government (c) The sanggunians of component cities and municipalities may, in consultation with the Philippine Historical Commission, change the name of the following within its territorial jurisdiction: city and municipal barangays => upon recommendation of the sangguniang barangay concerned; city, municipal and barangay roads, avenues, boulevards, thoroughfares, and bridges; city and municipal public elementary, secondary and vocational or technical schools, post-secondary and other tertiary schools; city and municipal hospitals, health centers and other health facilities; and Any other public place or building owned by the municipal government. None of the foregoing local government units, institutions, places, or buildings shall be named after a living person, nor may a change of name be made Unless: for a justifiable reason and, in any case, not oftener than once every ten (10) years. The name of a local government unit or a public place, street or structure with historical, cultural, or ethnic significance shall not be changed, unless by a unanimous vote of the sanggunian concerned and in consultation with the PHC. (e) A change of name of a public school shall be made only upon the recommendation of the local school board concerned.cralaw A change of name of public hospitals, health centers, and other health facilities shall be made => only upon the recommendation of the local health board concerned Effectivity of the change of name of any local government=> only upon ratification in a plebiscite conducted for the purpose in the political unit directly affected. In any change of name, the Office of the President, the representative of the legislative district concerned, and the Bureau of Posts shall be notified 5

SEC. 9. Abolition of Local Government Units. A local government unit may be abolished when its income, population, or land area has been irreversibly reduced to less than the minimum standards prescribed for its creation The law or ordinance abolishing a local government unit shall specify the province, city, municipality, or barangay with which the local government unit sought to be abolished will be incorporated or merged

SEC. 10. Plebiscite Requirement. - No creation, division, merger, abolition, or substantial alteration of boundaries of local government units shall take effect unless approved by a majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite called for the purpose in the political unit or units directly affected. Said plebiscite shall be conducted by the COMELEC (Comelec) within 120 days from the date of effectivity of the law or ordinance effecting such action unless said law or ordinance fixes another date SEC. 11. Selection and Transfer of Local Government Site, Offices and Facilities. (a) The law or ordinance creating or merging local government units => shall specify the seat of government from where governmental and corporate services shall be delivered. In selecting said site, factors relating to: geographical centrality, accessibility, availability of transportation and communication facilities, drainage and sanitation, development and economic progress, and other relevant considerations shall be taken into account (b)When conditions and developments in the local government unit concerned have significantly changed subsequent to the establishment of the seat of government, its sanggunian may, after public hearing and by a vote of two-thirds (2/3) of all its members, transfer the same to a site better suited to its needs. Provided: no such transfer shall be made outside the territorial boundaries of the local government unit concerned The old site, together with the improvements thereon, may be disposed of: by sale or lease or converted to such other use as the sanggunian concerned may deem beneficial to the local government unit concerned and its inhabitants. (c) Local government offices and facilities shall not be transferred, relocated, or converted to other uses XPN: Public hearings are first conducted for the purpose and the concurrence of the majority of the members of the sanggunian concerned

Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

o SEC. 14. Beginning of Corporate Existence. - When a new local government unit is created, its corporate existence shall commence: upon the election and qualification of its chief executive and a majority of the members of its sanggunian, unless some other time is fixed therefor by the law or ordinance creating it

Curative laws, which in essence are retrospective, and aimed at giving "validity to acts done that would have been invalid under existing laws, as if existing laws have been complied with," are validly accepted in this jurisdiction, subject to the usual qualification against impairment of vested rights.

SENATOR HEHERSON T. ALVAREZ et al vs. HON. TEOFISTO T. GUINGONA, JR Issue: W/N the Internal Revenue Allotments (IRAs) are to be included in the computation of the average annual income of a municipality for purposes of its conversion into an independent component city Held: Yes o A Local Government Unit is a political subdivision of the State which is constituted by law and possessed of substantial control over its own affairs. o Every LGU is vested with the following rights: o the right to create and broaden its own source of revenue; o the right to be allocated a just share in national taxes, such share being in the form of IRAs; and o the right to be given its equitable share in the proceeds of the utilization and development of the national wealth, if any, within its territorial boundaries o Section 450 (c) of the LGC provides that "the average annual income shall include the income accruing to the general fund, exclusive of special funds, transfers, and non-recurring income." o To reiterate, IRAs are a regular, recurring item of income. Issue: W/N RA 7720 can be considered to originate from the HR, hence, valid Held: Yes o It cannot be denied that HB No. 8817 was filed in the House of Representatives first before SB No. 1243 was filed in the Senate. -> No violation of Sec. 24 Art. VI of the Constitution o Tolentino vs. Secretary of Finance: It is not the law but the revenue bill which is required by the Constitution to "originate exclusively" in HR o Presumption of Constitutionality Dual Personality SEC. 15. Political and Corporate Nature of Local Government Units. Every local government unit created or recognized under this Code is a body politic and corporate endowed with powers to be exercised by it in conformity with law. As such, it shall exercise powers as: a political subdivision of the national government and as a corporate entity representing the inhabitants of its territory Delegatas Potestas non Potest Delegare RUBI, ET AL. (manguianes) vs. THE PROVINCIAL BOARD OF MINDORO o Cincinnati, W. & Z. R. Co. vs. Comm'rs. Clinton County -> What is forbidden is the delegation of power to make the law (which necessarily involves a discretion as to what it shall be) and not the conferring of an authority or discretion as to its execution, to be exercised under and in pursuance of the law, as what is done in this case Wayman vs. Southard: Discretion may be committed by the Legislature to an executive department or official -> based on necessity In the case at bar, The Philippine Legislature has conferred authority upon the Province of Mindoro, to be exercised by the provincial governor and the provincial board. o Reason: As officials charged with the administration of the province and the protection of its inhabitants, they are better fitted to select sites which have the conditions most favorable for improving the people who have the misfortune of being in a backward state

EMMANUEL PELAEZ vs. THE AUDITOR GENERAL o RA 2370: o GR:Barrios may not be created or their boundaries altered nor their names changed o XPN: By Act of Congress or of the corresponding provincial board upon petition of a majority of the voters in the areas affected and the recommendation of the council of the municipality or municipalities in which the proposed barrio is situated Respondents reliance upon Municipality of Cardona vs. Municipality of Binagonan is untenable -> Do not involve creation of a new municipality but a mere transfer of territory from an already existing municipality (Cardona) to another Congress may delegate to another branch of the Government the power to fill in the details in the execution, enforcement or administration of a law. Requirements for a valid delegation: o Law be complete in itself -> set forth the policy to be executed, carried out or implemented by the delegate and o Fix a standard the limits of which are sufficiently determinate or determinable to which the delegate must conform in the performance of his functions Sec. 68 of RAC do not conform to these requirements. o No policy to be carried out or implemented by the President Creation of municipalities -> not an administrative function but -> essentially and eminently legislative in character o The question of whether or not "public interest" demands the exercise of such power is a legislative question Sec. 10 (1) of Article VII of Consti: Power of Control in Executive Departments -> This power is not granted to the President as far as local governments are concerned o Sec. 68 of RAC is unconstitutional -> Instead of giving the President less power over local governments than that vested in him over the executive departments, bureaus or offices, it reverses the process and does the exact opposite, by conferring upon him more power over municipal corporations than that which he has over said executive departments, bureaus or offices.

o o

MUNICIPALITY OF KAPALONG vs. HON. FELIX L. MOYA Facts: Municipality of Sto. Tomas, created by then President Garcia, which asserted jurisdiction over 8 barrios of petitioner, brought the subject action to the respondent judge to settle the conflicts on boundaries with the petitioner. o The court considered petitioners premise that the ruling of the court in Pelaez vs. Auditor General is clear that the President has no power to create municipalities. o Thus, there is no Municipality of Santo Tomas to speak of. It has no right to assert, no cause of action, no corporate existence at all, and it must perforce remain part and parcel of Kapalong.

o o

MUNICIPALITY OF SAN NARCISO vs. HON. ANTONIO V. MENDEZ o Municipality of San Andres had been in existence for more than 6 years when the decision in Pelaez v. Auditor General was promulgated. o The ruling could have sounded the call for a similar declaration of the unconstitutionality of EO 353 but it was not the case -> EO 174 was promulgated The Municipality of San Andres had been considered to be one of the 12 municipalities composing the Third District of the province of Quezon, under the ordinance apportioning the seats of the House of Representatives, which is equally significant to the intention of Sec. 442(d) of the LGC The power to create political subdivisions is a function of the legislature. Congress did just that when it has incorporated Sec. 442(d) in the Code

THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS vs. JOSE O. VERA Any attempt to abdicate the legislative power is unconstitutional and void, on the principle that potestas delegata non delegare potest. o John Locke: "The legislative neither must nor can transfer the power of making laws to anybody else, or place it anywhere but where the people have." o XPN: o Creation of the municipalities exercising local self government -> Such legislation is not regarded as a transfer 6

Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

of general legislative power, but rather as the grant of the authority to prescribed local regulations, according to immemorial practice, subject of course to the interposition of the superior in cases of necessity (Stoutenburgh vs. Hennick) o Section 14, paragraph 2, of article VI of the Constitution: The President, subject to such limitations and restrictions as it may impose, to fix within specified limits, tariff rates, import or export quotas, and tonnage and wharfage dues o Section 16 of the Constitution: Authority of the President to promulgate rules and regulations in times of war or other national emergency Test for undue delegation: To inquire whether the statute was complete in all its terms and provisions when it left the hands of the legislature so that nothing was left to the judgment of any other appointee or delegate of the legislature o The probation Act does not, by the force of any of its provisions, fix and impose upon the provincial boards any standard or guide in the exercise of their discretionary power. o The provincial boards of the various provinces are to determine for themselves, whether the Probation Law shall apply to their provinces or not at all. The principle which permits the legislature to provide that the administrative agent may determine when the circumstances are such as require the application of a law is defended upon the ground that at the time this authority is granted, the rule of public policy, which is the essence of the legislative act, is determined by the legislature. o In the case at bar, the legislature has not made the operation of the Prohibition Act contingent upon specified facts or conditions to be ascertained by the provincial board.

MMDA vs. VIRON TRANSPORTATION CO., INC. Facts: Herein petitioners assail the order of the RTC of Manila declaring EO 179 (Greater Manila Mass Transport System Project), issued by then President Gloria Arroyo ordering the implementation of MMDAs plan to decongest traffic by the closure of provincial bus terminals along EDSA and major thoroughfares in MM, unconstitutional and denying petitioners motion for reconsideration. o o While police power rests primarily with the legislature, such power may be delegated. By virtue of a valid delegation, the power may be exercised by the President and administrative boards as well as by the lawmaking bodies of municipal corporations or local governments under an express delegation by the LGC Under the provisions of E.O. No. 125, as amended, it is the DOTC, and not the MMDA, which is authorized to establish and implement a project such as the one subject of the cases at bar. o Thus, the President, although authorized to establish or cause the implementation of the Project, must exercise the authority through the instrumentality of the DOTC which, by law, is the primary implementing and administrative entity in the promotion, development and regulation of networks of transportation, and the one so authorized to establish and implement a project such as the Project in question. o By designating the MMDA as the implementing agency of the Project, the President clearly overstepped the limits of the authority conferred by law, rendering E.O. No. 179 ultra vires. It will be noted that the powers of the MMDA are limited to the following acts: formulation, coordination, regulation, implementation, preparation, management, monitoring, setting of policies, installation of a system and administration. o There is no syllable in R.A. No. 7924 (Act creating MMDA) that grants the MMDA police power, let alone legislative power. Even assuming arguendo that police power was delegated to the MMDA, its exercise of such power does not satisfy the two tests of a valid police power measure, viz: o the interest of the public generally, as distinguished from that of a particular class, requires its exercise; and o the means employed are reasonably necessary for the accomplishment of the purpose and not unduly oppressive upon individuals.

THE SOLICITOR GENERAL vs. THE METROPOLITAN MANILA Facts: MMA issued Ordinance No. 11 of 1991 authorizing itself to detach the license plate/tow and impound attended/ unattended/ abandoned motor vehicles illegally parked or obstructing the flow of traffic in Metro Manila Issue: W/N there was an undue delegation of legislative power under EO 392 as stated by the OSG in its comment Held: No o The Court holds that there is a valid delegation of legislative power to promulgate such measures, it appearing that the requisites of such delegation are present. These requisites are. o the completeness of the statute making the delegation; and Under the first requirement, the statute must leave the legislature complete in all its terms and provisions such that all the delegate will have to do when the statute reaches it is to implement it. What only can be delegated is not the discretion to determine what the law shall be but the discretion to determine how the law shall be enforced. This has been done in the case at bar. o the presence of a sufficient standard It is settled that the "convenience and welfare" of the public, particularly the motorists and passengers in the case at bar, is an acceptable sufficient standard to delimit the delegate's authority. However, the question now left is whether the exercise of such delegated power is valid. No. o Test of the validity of the exercise of the delegated legislative power -> Requisites of a valid ordinance: o must not contravene the Constitution or any statute; -> not passed this criterion since the ordinance is in contradiction with PD 1605, a statute o must not be unfair or oppressive; o must not be partial or discriminatory; o must not prohibit but may regulate trade; o must not be unreasonable; and o must be general and consistent with public policy

General Welfare Clause SEC. 16. General Welfare. Every local government unit shall exercise the powers Expressly granted, Necessarily implied therefrom, Necessary, appropriate, or incidental for its efficient and effective governance, and Essential to the promotion of the general welfare. Duties of local government within their respective territorial jurisdictions under this provision: Ensure and support the preservation and enrichment of culture, Promote health and safety, Enhance the right of the people to a balanced ecology, Encourage and support the development of appropriate and selfreliant scientific and technological capabilities, Improve public morals, Enhance economic prosperity and social justice, Promote full employment among their residents, Maintain peace and order, and Preserve the comfort and convenience of their inhabitants. RAMON FABIE, ET AL. v s. THE CITY OF MANILA It is undoubtedly one of the fundamental duties of the city of Manila to make all reasonable regulations looking to the preservation and security of the general health of the community, and the protection of life and property from loss or destruction by fire. All such regulations have their sanction in what is termed the police power. US vs Toribio First, that the interests of the public generally, as distinguished from those of a particular class, require such interference; and, second, that the means are reasonably necessary for the accomplishment of the purpose, and not unduly oppressive upon individuals. The legislature may not, under the guise of protecting the public interest, arbitrary interfere with private business, or impose 7

Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

unusual and unnecessary restrictions upon lawful occupations. In other words, is determination as to what is a proper exercise of its police powers is not conclusive, but is subject to the supervision of the court. In the instant case, the requirement that buildings should "abut or face upon a public street or alley or on a private street or alley which has been officially approved," is reasonably necessary to secure the end in view, to wit: o It prevents the huddling and crowding of buildings in irregular masses on single or adjoining tracts of land, and secures an air space on at least one side of each new residence o It promotes the safety and security of the citizens of Manila and of their property against fire and disease, especially epidemic disease, by securing the easy and unimpeded approach to all new buildings That the ordinance is not "unduly oppressive upon individuals" becomes very clear when the nature and extent of the limitations imposed by its provisions upon the use of private property are considered with relation to the public interests, the public health and safety, which the ordinance seeks to secure. The ordinance proviso is manifestly intended to subserve the public health and safety of the citizens of Manila generally and was not conceived in favor of any class or of particular individuals. Those charged with the public welfare and safety of the city deemed the enactment of the ordinance necessary to secure these purposes, and it cannot be doubted that if its enactment was reasonably necessary to that end it was and is a due and proper exercise of the police power. We are of opinion that the enforcement of its provisions cannot fail to redound to the public good, and that it should be sustained on the principle that "the welfare of the people is the highest law" (salus populi suprema est lex).

THE CITY OF MANILA vs. ARCADIO PALLUNGNA In Uy Ha vs. The City Mayor, et al: o Ordinance No. 3628 seeks to regulate and license the operation of "pinball machines" within the City of Manila upon payment of an annual license of P300.00 for each "pinball machines" o Such ordinance is ultra vires, it being an exercise of power not granted by law to the City of Manila since those devices are prohibited by law, hence, not subject to regulation. Ordinance No. 3628 is ultra vires, not because it is a tax measure, but because it was enacted beyond the power granted by law to the City of Manila. Any attempt to collect any license fee under said ordinance is illegal.

THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS vs. TEOFILO GABRIEL Under its police power, the City Council of Manila has authority to regulate and control public auctions within its city boundaries. o The ordinance is in the nature of a police regulation, and to that extent is intended as a business regulation. o It is no more than a regulation of the business, affairs of the city, and is a matter in the discretion of the council acting under its police power. There is no discrimination in the ordinance. o It applies to all kinds and classes of people alike doing business within the prohibited area, and no person within the city limits has any legal or constitutional right to auction his goods without a license from, or the consent of, the city o Hence, so long as the ordinance is uniform, the city has a legal right to specify how, when, where, and in what manner goods may be sold at auction within its limits, and to prohibit their sale in any other manner.

THE UNITED STATES vs. SILVESTRE POMPEYA The Philippine Legislature has power to legislate upon all subjects affecting the people of the Philippine Islands which has not been delegated to Congress or expressly prohibited by said Organic Act. o Police power the power of the government, inherent in every sovereign, and cannot be limited The power vested in the legislature to make such laws as they shall judge to be for the good of the state and its subjects The police power of the state includes not only the public health and safety, but also the public welfare, protection against impositions, and generally the public's best interest. It so extensive and all pervading, that the courts refuse to lay down a general rule defining it, but decide each specific case on its merits

EUSEBIO PELINO vs. JOSE ICHON, ET AL The portion of ordinance No. 8 which led the court to declare it null and void is that one authorizing as many cockpits in the municipality as there are applicants therefor. However, the municipal council acted within its powers in enacting this ordinance and it is granted discretion by law to regulate or prohibit cockpits (section 2243 of the Revised Administrative Code). o When the council does not so prohibit, these businesses are deemed to be authorized subject to its regulation. This power to regulate includes the power to fix its number, inasmuch as the law neither fixes it nor limits it to one.

ERMITA-MALATE HOTEL vs. THE HONORABLE CITY MAYOR OF MANILA POLICE POWER; MANIFESTATION OF. Ordinance No. 4760 of the City of Manila is a manifestation of a police power measure specifically aimed to safeguard public morals. As such it is immune from any imputation of nullity resting purely on conjecture and unsupported by anything of substance. To hold otherwise would be to unduly restrict and narrow the scope of police power which has been properly characterized as the most essential, insistent and the least limitable of powers extending as it does "to all the great public needs." There is no question but that the challenged ordinance was precisely enacted to minimize certain practices hurtful to public morals. The explanatory note included as annex to the stipulation of facts speaks of the alarming increase in the rate of prostitution, adultery and fornication in Manila traceable in great part to the existence of motels, which "provide a necessary atmosphere for clandestine entry, presence and exit" and thus become the "ideal haven for prostitutes and thrill seekers." LICENSES INCIDENTAL TO. Municipal license fees can be classified into those imposed for regulating occupations or regular enterprises, for the regulation or restriction of non-useful occupations or enterprises and for revenue purposes only. Licenses for non-useful occupations are incidental to the police power, and the right to exact a fee may be implied from the power to license and regulate, but in taking the amount of license fees the municipal corporations are allowed a wide discretion in this class of cases. Aside from applying the well known legal principle that municipal ordinances must not be unreasonable, oppressive, or tyrannical, courts have, as a general rule, declined to interfere with such discretion. The desirability of imposing restraint upon the number of persons who might otherwise engage in non-useful enterprises is, of course, generally an important factor in the 8

THE UNITED STATES vs. PRUDENCIO SALAVERIA Two branches of the general welfare clause: o One branch attaches itself to the main trunk of municipal authority, and relates to such ordinances and regulations as may be necessary to carry into effect and discharge the powers and duties conferred upon the municipal council by law. o The second branch of the clause is much more independent of the specific functions of the council which are enumerated by law this authorizes such ordinances "as shall seem necessary and proper to provide for the health and safety, promote the prosperity, improve the morals, peace, good order, comfort, and convenience of the municipality and the inhabitants thereof, and for the protection of property therein." The constitutional provision that no person shall be deprived of liberty without due process of law is not violated by this ordinance. Liberty of action by the individual is not unduly circumscribed; that is, it is not unduly circumscribed if we have in mind the correct notion of this "the greatest of all rights." o The local legislative body, by enacting the ordinance, has in effect given notice that the regulations are essential to the well being of the people.

Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

determination of the amount of this kind of license fee. (Cu Unjieng v. Patstone [1922], 42 Phil,, 818, 828). Admittedly there was a decided increase of the annual license fees provided for by the challenged ordinance for both hotels and motels, 150% for the former and over 200% for the latter, first-class motels being required to pay a P6,000 annual fee and second-class motels, P4,500 yearly.this Court affirmed the doctrine earlier announced by the American Supreme Court that taxation may be made to implement the state's police power. MUNICIPAL ORDINANCES; PROHIBITIONS IN. The provision in Ordinance No. 4760 of the City of Manila making it unlawful for OMKA of any hotel, motel, lodging house, tavern, common inn or the like, to lease or rent any room or portion thereof more than twice every 24 hours, with a proviso that in all cases full payment shall be charged, cannot be viewed as transgression against the command of due process. The prohibition is neither unreasonable nor arbitrary, because there appears a correspondence between the undeniable existence of an undesirable situation and the legislative attempt at correction. Moreover, every regulation of conduct amounts to curtailment of liberty, which cannot be absolute. [G.R. No. 118127. April 12, 2005.] CITY OF MANILA, HON. ALFREDO S. LIM as the Mayor of the City of Manila vs. HON. PERFECTO A.S. LAGUIO, JR., as Presiding Judge, RTC, Manila and MALATE TOURIST DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, respondents. FACTS:Enacted by the City Council 9 on 9 March 1993 and approved by petitioner City Mayor on 30 March 1993, the said Ordinance is entitled AN ORDINANCE PROHIBITING THE ESTABLISHMENT OR OPERATION OF BUSINESSES PROVIDING CERTAIN FORMS OF AMUSEMENT, ENTERTAINMENT, SERVICES AND FACILITIES IN THE ERMITA-MALATE AREA, PRESCRIBING PENALTIES FOR VIOLATION THEREOF, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES SECTION 1.Any provision of existing laws and ordinances to the contrary notwithstanding, no person, partnership, corporation or entity shall, in the ErmitaMalate area bounded by Teodoro M. Kalaw Sr. Street in the North, Taft Avenue in the East, Vito Cruz Street in the South and Roxas Boulevard in the West, pursuant to P.D. 499 be allowed or authorized to contract and engage in, any business providing certain forms of amusement, entertainment, services and facilities where women are used as tools in entertainment and which tend to disturb the community, annoy the inhabitants, and adversely affect the social and moral welfare of the community, such as but not limited to: 1.SaunaParlors2.Massage Parlors3.Karaoke Bars4.Beerhouses5.Night Clubs6.Day Clubs7.Super Clubs8.Discotheques9.Cabarets10.Dance Halls11.Motels12.Inns Private respondent Malate Tourist Development Corporation (MTDC) is a corporation engaged in the business of operating hotels, motels, hostels and lodging houses. It built and opened Victoria Court in Malate which was licensed as a motel although duly accredited with the Department of Tourism as a hotel. MTDC prayed to the court that the Ordinance be declared invalid and unconstitutional. MTDC argued that the Ordinance erroneously and improperly included in its enumeration of prohibited establishments, motels and inns such as MTDCs Victoria Court considering that these were not establishments for amusement or entertainment and they were not services or facilities for entertainment, nor did they use women as tools for entertainment, and neither did they disturb the community, annoy the inhabitants or adversely affect the social and moral welfare of the community. In their Answer, petitioners City of Manila contend that the assailed Ordinance was enacted in the exercise of the inherent and plenary power of the State and the general welfare clause exercised by local government units provided for in Art. 3, Sec. 18 (kk) of the Revised Charter of Manila and conjunctively, Section 458 (a) 4 (vii) of the LGU Code.They allege that the Ordinance is a valid exercise of police power; it does not contravene P.D. 499; and that it enjoys the presumption of validity. ARTICLE III THE MUNICIPAL BOARD Section 18.Legislative powers. The Municipal Board shall have the following legislative powers: xxxxxxxxx Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

(kk)To enact all ordinances it may deem necessary and proper for the sanitation and safety, the furtherance of the prosperity, and the promotion of the morality, peace, good order, comfort, convenience, and general welfare of the city and its inhabitants, and such others as may be necessary to carry into effect and discharge the powers and duties conferred by this chapter; and to fix penalties for the violation of ordinances which shall not exceed two hundred pesos fine or six months' imprisonment, or both such fine and imprisonment, for a single offense. Private respondent maintains that the Ordinance is ultra vires and that it is void for being repugnant to the general law. That the questioned Ordinance is not a valid exercise of police power Respondent Judge Laguio issued an ex-parte temporary restraining order against the enforcement of the Ordinance. And granted the writ of preliminary injunction prayed for by MTDC. Hence this petition. ISSUE: WON the ordinance is a valid exercise of the general welfare clause of LGUs. HELD: The Ordinance is so replete with constitutional infirmities that almost every sentence thereof violates a constitutional provision. Anent the first criterion of a valid oridinance, (1) must not contravene the Constitution or any statute - ordinances shall only be valid when they are not contrary to the Constitution and to the laws. The Ordinance must satisfy two requirements: it must pass muster under the test of constitutionality and the test of consistency with the prevailing laws. That ordinances should be constitutional uphold the principle of the supremacy of the Constitution. The requirement that the enactment must not violate existing law gives stress to the precept that local government units are able to legislate only by virtue of their derivative legislative power, a delegation of legislative power from the national legislature. The delegate cannot be superior to the principal or exercise powers higher than those of the latter. The Ordinance was passed by the City Council in the exercise of its police power, an enactment of the City Council acting as agent of Congress. Local government units, as agencies of the State, are endowed with police power in order to effectively accomplish and carry out the declared objects of their creation. This delegated police power is found in Section 16 of the Code, known as the general welfare clause. The inquiry in this Petition is concerned with the validity of the exercise of such delegated power. REQUISITES FOR THE VALID EXERCISE OF POLICE POWER ARE NOT MET - To successfully invoke the exercise of police power as the rationale for the enactment of the Ordinance, and to free it from the imputation of constitutional infirmity, not only must it appear that the interests of the public generally, as distinguished from those of a particular class, require an interference with private rights, but the means adopted must be reasonably necessary for the accomplishment of the purpose and not unduly oppressive upon individuals. It must be evident that no other alternative for the accomplishment of the purpose less intrusive of private rights can work. A reasonable relation must exist between the purposes of the police measure and the means employed for its accomplishment, for even under the guise of protecting the public interest, personal rights and those pertaining to private property will not be permitted to be arbitrarily invaded. Lacking a concurrence of these two requisites, the police measure shall be struck down as an arbitrary intrusion into private rights a violation of the due process clause. The Ordinance was enacted to address and arrest the social ills purportedly spawned by the establishments in the Ermita-Malate area which are allegedly operated under the deceptive veneer of legitimate, licensed and tax-paying nightclubs, bars, karaoke bars, girlie houses, cocktail lounges, hotels and motels. The object of the Ordinance was, accordingly, the promotion and protection of the social and moral values of the community. Granting for the sake of argument that the objectives of the Ordinance are within the scope of the City Council's police powers, the means employed for the accomplishment thereof were unreasonable and unduly oppressive. However, the worthy aim of fostering public morals and the eradication of the community's social ills can be achieved through means less restrictive of private rights; it can be attained by reasonable restrictions rather than by an absolute prohibition. The closing down and transfer of businesses or their conversion into businesses "allowed" under the Ordinance have no reasonable relation to the accomplishment of its purposes. The enumerated establishments are lawful pursuits which are not per se offensive to the moral welfare of the community. 9

That these are used as arenas to consummate illicit sexual affairs and as venues to further the illegal prostitution is of no moment. We lay stress on the acrid truth that sexual immorality, being a human frailty, may take place in the most innocent of places that it may even take place in the substitute establishments enumerated under Section 3 of the Ordinance. The Ordinance seeks to legislate morality but fails to address the core issues of morality. Try as the Ordinance may to shape morality, it should not foster the illusion that it can make a moral man out of it because immorality is not a thing, a building or establishment; it is in the hearts of men. The City Council instead should regulate human conduct that occurs inside the establishments, but not to the detriment of liberty and privacy which are covenants, premiums and blessings of democracy. MEANS EMPLOYED ARE CONSTITUTIONALLY INFIRM - It is readily apparent that the means employed by the Ordinance for the achievement of its purposes, the governmental interference itself, infringes on the constitutional guarantees of a person's fundamental right to liberty and property. Liberty as guaranteed by the Constitution was defined by Justice Malcolm to include "the right to exist and the right to be free from arbitrary restraint or servitude. The term cannot be dwarfed into mere freedom from physical restraint of the person of the citizen, but is deemed to embrace the right of man to enjoy the faculties with which he has been endowed by his Creator, subject only to such restraint as are necessary for the common welfare." In accordance with this case, the rights of the citizen to be free to use his faculties in all lawful ways; to live and work where he will; to earn his livelihood by any lawful calling; and to pursue any avocation are all deemed embraced in the concept of liberty. [G.R. No. 122846. January 20, 2009.] WHITE LIGHT CORPORATION, TITANIUM CORPORATION and STA. MESA TOURIST & DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, petitioners vs. CITY OF MANILA, represented by MAYOR ALFREDO S. LIM, respondent. FACTS: City Mayor Alfredo S. Lim (Mayor Lim) signed into law the Ordinance prohibiting the motels and inns, among other establishments, within the ErmitaMalate area from offering short-time admission, as well as pro-rated or "wash up" rates for such abbreviated stays. It also prohibits renting out a room more than twice a day. Manila City Ordinance No. 7774 entitled, "An Ordinance Prohibiting Short-Time Admission, Short-Time Admission Rates, and Wash-Up Rate Schemes in Hotels, Motels, Inns, Lodging Houses, Pension Houses, and Similar Establishments in the City of Manila" SEC. 1.Declaration of Policy. It is hereby the declared policy of the City Government to protect the best interest, health and welfare, and the morality of its constituents in general and the youth in particular. SEC. 4.Definition of Term[s]. Short-time admission shall mean admittance and charging of room rate for less than twelve (12) hours at any given time or the renting out of rooms more than twice a day or any other term that may be concocted by owners or managers of said establishments but would mean the same or would bear the same meaning. The Malate Tourist and Development Corporation (MTDC) filed for a TRO with (RTC) of Manila praying that the Ordinance, be declared invalid and unconstitutional. MTDC claimed that as owner and operator of the Victoria Court in Malate, Manila it was authorized by P.D. No. 259 to admit customers on a short time basis as well as to charge customers wash up rates for stays of only three hours. Petitioners White Light Corporation (WLC), as operators of drive-in hotels and motels in Manila (Anito group of companies), filed a motion to intervene. Petitioners argued that the Ordinance is unconstitutional and void since it violates the right to privacy and the freedom of movement; it is an invalid exercise of police power; and it is an unreasonable and oppressive interference in their business. RTC rendered a decision declaring the Ordinance null and void. The RTC noted that the ordinance "strikes at the personal liberty of the individual guaranteed and jealously guarded by the Constitution." Reference was made to the provisions of the Constitution encouraging private enterprises and the incentive to needed investment, as well as the right to operate economic enterprises. Finally, from the Notes in Public Corporation Rivad, Sherine L., 2011 0007 1stSem AY 2013-2014, Arellano University School of Law

observation that the illicit relationships the Ordinance sought to dissuade could nonetheless be consummated by simply paying for a 12-hour stay. The City later filed a petition for review on certiorari with the Supreme Court. ISSUE: WON Ordinance is a valid exercise of police power pursuant to Section 458 (4) (iv) of the LGC HELD: Ordinance 7774 is unconstitutional Police power, while incapable of an exact definition, has been purposely veiled in general terms to underscore its comprehensiveness to meet all exigencies and provide enough room for an efficient and flexible response as the conditions warrant. The apparent goal of the Ordinance is to minimize if not eliminate the use of the covered establishments for illicit sex, prostitution, drug use and alike. These goals, by themselves, are unimpeachable and certainly fall within the ambit of the police power of the State. Yet the desirability of these ends do not sanctify any and all means for their achievement. Those means must align with the Constitution, and our emerging sophisticated analysis of its guarantees to the people. The due process guaranty has traditionally been interpreted as imposing two related but distinct restrictions on government, "procedural due process" and "substantive due process". The general test of the validity of an ordinance on substantive due process grounds is best tested when assessed with the evolved footnote 4 test laid down by the U.S. Supreme Court in U.S. v. Carolene Products. The general test of the validity of an ordinance on substantive due process grounds is best tested when assessed with the evolved footnote 4 test laid down by the U.S. Supreme Court in U.S. v. Carolene Products. Footnote 4 of the Carolene Products case acknowledged that the judiciary would defer to the legislature unless there is a discrimination against a "discrete and insular" minority or infringement of a "fundamental right". Consequently, two standards of judicial review were established: strict scrutiny for laws dealing with freedom of the mind or restricting the political process, and the rational basis standard of review for economic legislation. A third standard, denominated as heightened or immediate scrutiny, was later adopted by the U.S. Supreme Court for evaluating classifications based on gender 53 and legitimacy. 54 Immediate scrutiny was adopted by the U.S. Supreme Court in Craig,55 after the Court declined to do so in Reed v. Reed.56 While the test may have first been articulated in equal protection analysis, it has in the United States since been applied in all substantive due process cases as well. We ourselves have often applied the rational basis test mainly in analysis of equal protection challenges. Using the rational basis examination, laws or ordinances are upheld if they rationally further a legitimate governmental interest.Under intermediate review, governmental interest is extensively examined and the availability of less restrictive measures is considered. Applying strict scrutiny, the focus is on the presence of compelling, rather than substantial, governmental interest and on the absence of less restrictive means for achieving that interest. It cannot be denied that the primary animus behind the ordinance is the curtailment of sexual behavior. The establishments have gained notoriety as venue of 'prostitution, adultery and fornications'. Whether or not this depiction of a mise-en-scene of vice is accurate, it cannot be denied that legitimate sexual behavior among consenting married or consenting single adults which is constitutionally protected will be curtailed as well. We cannot discount other legitimate activities which the Ordinance would proscribe or impair. There are very legitimate uses for a wash rate or renting the room out for more than twice a day. Entire families are known to choose to pass the time in a motel or hotel whilst the power is momentarily out in their homes. In transit passengers who wish to wash up and rest between trips have a legitimate purpose for abbreviated stays in motels or hotels. Indeed any person or groups of persons in need of comfortable private spaces for a span of a few hours with purposes other than having sex or using illegal drugs can legitimately look to staying in a motel or hotel as a convenient alternative. That the Ordinance prevents the lawful uses of a wash rate depriving patrons of a product and the petitioners of lucrative business ties in with another constitutional requisite for the legitimacy of the Ordinance as a police power measure. It must appear that the interests of the public generally, as distinguished from those of a 10

particular class, require an interference with private rights and the means must be reasonably necessary for the accomplishment of the purpose and not unduly oppressive of private rights. The behavior which the Ordinance seeks to curtail is in fact already prohibited and could in fact be diminished simply by applying existing laws. Less intrusive measures such as curbing the proliferation of prostitutes and drug dealers through active police work would be more effective in easing the situation. So would the strict enforcement of existing laws and regulations penalizing prostitution and drug use. These measures would have minimal intrusion on the businesses of the petitioners and other legitimate merchants. Further, it is apparent that the Ordinance can easily be circumvented by merely paying the whole day rate without any hindrance to those engaged in illicit activities. Moreover, drug dealers and prostitutes can in fact collect "wash rates" from their clientele by charging their customers a portion of the rent for motel rooms and even apartments. SORIANO, NICKOLAI CESAR JUANA RIVERA, petitioner, vs. RICHARD CAMPBELL, judge of the Court of First Instance of the city of Manila, respondent. (G.R. No. L-11119 March 23, 1916) FACTS:

water supply beyond the limits of the municipality is within the competency of the legislature, and that the municipality may exercise police power in the protection of the territory thus acquired to insure cleanliness, and prevent any business and conduct likely to corrupt the fountain of water supply for the city.' (28 Cyc., 703, 704.)

VICENTE DE LA CRUZ, RENATO ALIPIO, JOSE TORRES III, LEONCIOCORPUZ, TERESITACALOT, ROSALIA FERNANDEZ, ELIZABETH VELASCO, NANETTE VILLANUEVA, HONORATO BUENAVENTURA, RUBEN DE CASTRO, VICENTE ROXAS, RICARDO DAMIAN, DOMDINOROMDINA, ANGELINA OBLIGACION, CONRADO GREGORIO, TEODORO REYES, LYDIA ATRACTIVO, NAPOLEON MENDOZA, PERFECTO GUMATAY, ANDRES SABANGAN, ROSITA DURAN, SOCORRO BERNARDEZ, and PEDRO GABRIEL, petitioners, vs. THE HONORABLE EDGARDO L. PARAS, MATIAS RAMIREZ as the Municipal Mayor, MARIO MENDOZA as the Municipal Vice-Mayor, and THE MUNICIPAL COUNCIL OF BOCAUE, BULACAN, respondents (G.R. No. L-42571-72 July 25, 1983) FACTS:

Petitioner was charged and convicted for willfully and unlawfully washing garments, articles of clothing, and fabrics in the waters of that part of the Mariquina River lying between the Santolan pumping station and the Boso-Boso dam, in the Province of Rizal, a place then occupied by duly authorized representatives and employees of the city of Manila, on or about May 11th, 1915, in violation of of subsection (f) of Sec. 4 of Ordinance No. 149. Petitioner admitted of committing the violation but alleges that the Municipal Court and CFI of Manila does not have jurisdiction over her case.