Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Japanese

Încărcat de

Maria AndersonTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Japanese

Încărcat de

Maria AndersonDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

I. Japanese has both short and long vowels and the distinction is often important.

In romanized Japanese, long vowels are marked with a macron, so that represents "long O".

II.

a a k ka s sa t ta n na h ha m ma y ya r ra w wa n g ga z za d

Hiragana characters ()

i i ki shi chi ni hi mi yu ri (w)o ru re u u ku su tsu nu fu mu e ke se te ne he me yo ro e o o ko so to no ho mo

gi ji

gu zu

ge ze zo go

da b ba p pa ky kya sh sha ch cha hy hya gy gya j ja by bya

ji bi pi

zu bu pu

de be pe

do bo po kyo

kyu shu chu hyu gyu ju byu

sho cho hyo gyo jo byo

a / like 'a' in "father"

III.

i / like 'i' in "machine" u / like 'oo' in "hoop" e / like 'e' in "set"

o / like 'o' in "rope"

n / short 'n' at the end of a syllable, pronounced as 'm' before 'b', 'p' or 'm'.

IV.

Note that "u" is often weak at the end of syllables. In particular, the common endings -desu and -masu are usually pronounced as "des'" and "mas'" respectively.

V.

VI. k / like 'k' in "king" g / like 'g' in "go" s / like 's' in "sit" z / like 'z' in "haze" t / like 't' in "top" d / like 'd' in "dog"

n / like 'n' in "nice" h / like 'h' in "help"

p / like 'p' in "pig" b / like 'b' in "bed" m / like 'm' in "mother" y / like 'y' in "yard"

r / like 'r' in "row" (actually a sound between 'l' and 'r', but closer to 'r') w like 'w' in "wall" sh / (s before i) like 'sh' in "sheep" j/ (d before i) like 'j' in "jar" ch / (t before i) like 'ch' in "touch" ts / (t before u) like 'ts' in "hot soup" f/ (h before u) like 'wh' in "who"

I. Japanese uses certain hiragana characters as particles which mark the grammatical function of a word or phrase in a sentence. Some hiragana are pronounced differently when used as a particle: VII. (topic marker) is pronounced wa, also in (kon'nichiwa) (direction marker) is pronounced e (possessive marker) is pronounced no Avoid placing too much emphasis on particular words or syllables. Japanese does have stress and intonation, but it is significantly flatter than English. Mastering word stress is a more advanced topic and neglecting it at this point should not interfere with meaning. Just trying to keep your

intonation relatively flat will make your attempts to speak Japanese more comprehensible to local listeners. When asking questions, you can raise the tone at the end, as in English.

VIII. Hello. Konnichiwa. (kon-nee-chee-WAH) How are you? O-genki desu ka? (oh-GEN-kee dess-KAH?) Fine, thank you. Genki desu. (GEN-kee dess) What is your name? O-namae wa nan desu ka?

(oh-NAH-mah-eh wah NAHN dess-KAH?)

My name is ____ . ____ Watashi no namae wa ____ desu. (wah-TAH-shee no nah-mah-eh wa ____ dess) Nice to meet you. Hajimemashite. (hah-jee-meh-MASH-teh) Please. (request) Onegai shimasu. (oh-neh-gigh shee-moss) Please. (offer) Dzo. (DOH-zo) Thank you. Dmo arigat. (doh-moh ah-ree-GAH-toh) You're welcome. D itashi mashite. (doh EE-tah-shee mosh-teh) Yes. Hai. (HIGH) No. Iie. (EE-eh) Excuse me. Sumimasen. (soo-mee-mah-sen)

I'm sorry. Gomen-nasai. (goh-men-nah-sigh) Goodbye. (long-term) Saynara. (sa-YOH-nah-rah) Goodbye. (informal) Sore dewa. (SOH-reh deh-wah) I can't speak Japanese [well]. Nihongo o [yoku] hanasemasen. (nee-hohn-goh oh [yo-koo] hah-nah-seh-mah-sen) Do you speak English? Eigo o hanasemasuka? (AY-goh oh hah-nah-seh-moss-KAH?) Is there someone here who speaks English? Dareka eigo o hanasemasuka? (dah-reh-kah AY-goh oh hah-nahseh-moss-KAH?) Help! ! Tasukete! (tahs-keh-teh!) Look out! ! Abunai! (ah-boo-NIGH!) Good morning. Ohay gozaimasu. (oh-hah-YOH go-zigh-moss) Good evening. Konbanwa. (kohm-bahn-wah) Good night (to sleep) Oyasuminasai. (oh-yah-soo-mee-nah-sigh) I don't understand. Wakarimasen. (wah-kah-ree-mah-sen) Where is the toilet? Toire wa doko desu ka? (toy-reh wah DOH-koh dess kah?)

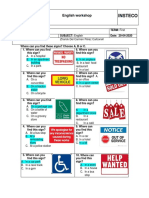

IX. Open Closed Entrance Exit Push Pull Toilet Men Women Forbidden

X. What part of "no" don't you understand? The Japanese are famously reluctant to say the word "no", and in fact the language's closest equivalent, iie, is largely limited to denying compliments you have received. ("Your Japanese is excellent! "Iie, it is very bad!"). But there are numerous other ways of expressing "no", so here are a few to watch out for. XI. Ii desu. Kekk desu. "It's good/excellent." Used when you don't want more beer, don't want your bent lunch microwaved, and generally are happy to keep things as they are. Accompany with teethsucking and handwaving to be sure to get your point across. Chotto muzukashii desu... Literally "it's a little difficult", but in practice "it's completely impossible." Often just abbreviated to sucking in air through teeth, saying "chotto" and looking pained. Take the hint. Mshiwakenai desukedo... "This is inexcusable but..." But no. Used by sales clerks and such to tell you that you cannot do or have something. Dame desu. "It's no good." Used by equals and superiors to tell you that you cannot do or have something. Chigaimasu. "It is different." What they really mean is "you're wrong". The casual form chigau and the Kansai contraction chau are also much used. Leave me alone. (hottoite.) Don't touch me! ! (sawaranaide!) I'll call the police. (keisatsu o yobimasu) Police! ! (keisatsu)

Stop! Thief! ! ! (mate! dorob!) I need your help. (tasukete kudasai) It's an emergency. (kinky desu) I'm lost. (maigo desu) I lost my bag. (kaban o nakushimashita) I dropped my wallet. (saifu o otoshimashita) I'm sick. (byki desu) I've been injured. (kega shimashita) Please call a doctor. (isha o yonde kudasai) Can I use your phone? ? (denwa o tsukatte iidesuka

XII. While Arabic (Western) numerals are employed for most uses in Japan, you will occasionally still spot Japanese numerals at eg. markets and the menus of fancy restaurants. The characters used are nearly identical to Chinese numerals, and like Chinese, Japanese uses groups of 4 digits, not 3. "One million" is thus (hyaku-man), literally "hundred tenthousands". There are both Japanese and Chinese readings for most numbers, but presented below are the more commonly used Chinese readings. Note that, due to superstition (shi also means "death"), 4 and 7 typically use the Japanese readings yon and nana instead. 0 , (zero or rei) 1 (ichi) 2 (ni) 3 (san) 4 (yon or shi) 5 (go) 6 (roku) 7 (nana or shichi) 8 (hachi) 9 (ky) 10 (j) 11 (j-ichi)

12 (j-ni) 13 (j-san) 14 (j-yon) 15 (j-go) 16 (j-roku) 17 (j-nana) 18 (j-hachi) 19 (j-kyuu) 20 (ni-j) 21 (ni-j-ichi) 22 (ni-j-ni) 23 (ni-j-san) 30 (san-j) 40 (yon-j) 50 (go-j)

60 (ro-ku-j) 70 (nana-j) 80 (hachi-j) 90 (ky-j) 100 (hyaku) 200 (ni-hyaku) 300 (san-byaku) 1000 (sen) 2000 (ni-sen) 10,000 (ichi-man) 1,000,000 (hyaku-man) 100,000,000 (ichi-oku) 1,000,000,000,000 (itch) 0.5 (rei ten go) 0.56 (rei ten g-roku)

number _____ (train, bus, etc.) _____ (____ ban) half (hanbun) less (few) (sukunai) more (many) (ooi)

now (ima) later (atode) before (mae ni) before ___ ___ ( ___ no mae ni) morning (asa) afternoon (gogo)

evening (ygata) night (yoru) Clock For clock times, you will be understood if you simply substitute gozen for "AM" and gogo for PM, although other time qualifiers like asa for morning and yoru for night may be more natural. The 24-hour clock is also commonly used in official contexts such as train schedules. six o'clock AM 6 (asa rokuji) nine o'clock AM 9 (gozen kuji) noon (shgo) one o'clock PM 1 (gogo ichiji.) two o'clock PM 2 (gogo niji) midnight 12 (yoru jniji) Duration _____ minute(s) _____ (fun or pun) _____ hour(s) _____ (jikan) _____ day(s) _____ (nichi) _____ week(s) _____ (shkan) _____ month(s) _____ (kagetsu)

_____ year(s) _____ (nen) Days today (ky) yesterday (kin) tomorrow (ashita) this week (konsh) last week (sensh) next week (raish) Sunday (nichiybi) Monday (getsuybi) Tuesday (kaybi) Wednesday (suiybi) Thursday (mokuybi) Friday (kin'ybi) Saturday (doybi) Days of the Month The 1st through the 10th of the month have special names:

First day of the month 1 (tsuitachi) Second day of the month 2 (futsuka) Third day of the month 3 (mikka) Fourth day of the month 4 (yokka) Fifth day of the month 5 (itsuka) Sixth day of the month 6 (muika) Seventh day of the month 7 (nanoka) Eighth day of the month 8 (yka) Ninth day of the month 9 (kokonoka) Tenth day of the month 10 (tka) The other days of the month are more orderly, just add the suffix -nichi to the ordinal number. Note that 14, 20, and 24 deviate from this pattern. Eleventh day of the month 11 (jichinichi) Fourteenth day of the month 14 (jyokka) Twentieth day of the month 20 (hatsuka) Twenty-fourth day of the month 24 (nijyokka) Months

Months are very orderly in Japanese, just add the suffix -gatsu to the ordinal number. January (ichigatsu) February (nigatsu) March (sangatsu) April (shigatsu) May (gogatsu) June (rokugatsu) July (shichigatsu) August (hachigatsu) September (kugatsu) October (jgatsu) November (jichigatsu) December (jnigatsu) Writing Dates are written in year/month/day (day of week) format, with markers: 2006321() Note that Imperial era years, based on the name and duration of the current Emperor's reign, are also frequently used. 2006 in the Gregorian calendar corresponds to Heisei 18 (18), which may be abbreviated as "H18". Dates like "18/03/24" (March 24, Heisei 18) are also occasionally seen.

XIII. Many of the English words for colors are widely used and understood by almost all Japanese. These are indicated after the slash. Note that some Japanese colors are normally suffixed with -iro () to distinguish between the color and the object. For example, cha means "tea", but chairo means "tea-color" "brown". XIV. black / (kuro / burakku) white / (shiro / howaito) gray () / (hai(iro) / gur) red / (aka / reddo) blue / (ao / bur) yellow () / (ki(iro) / ier) green / (midori / guriin) orange / (daidai / orenji) purple / (murasaki / ppuru) brown () / (cha(iro) / buraun)

How much is a ticket to _____? _____ (_____ made ikura desu ka?) One ticket to _____, please. _____ (_____ made ichimai onegaishimasu) Where does this train/bus go? [/] (kono densha/basu wa doko yuki desuka?) Where is the train/bus to _____? _____ [/]? (_____ yuki no densha/basu wa doko desuka?) Does this train/bus stop in _____? [/] _____ (kono densha/basu wa _____ ni tomarimasuka?) When does the train/bus for _____ leave? _____ [/](_____ yuki no densha/basu wa nanji ni shuppatsu shimasuka?) When will this train/bus arrive in _____? [/] _____ ? (kono densha/basu wa nanji ni _____ ni tsukimasuka?) Directions How do I get to _____ ? _____ ? (_____ wa dochira desu ka?) ...the train station? ... (eki...) ...the bus station? ... (basu tei..) ...the airport? ... (kk...) ...downtown? ... (machi no chshin...) ...the youth hostel? ... (ysu hosuteru...) ...the _____ hotel? _____ ... (hoteru...) ...the _____ embassy/consulate? _____/... (_____ taishikan/ryjikan...)

Where are there a lot of... ...? (...ga ooi tokoro wa doko desuka?) ...lodgings? ... (yado...) ...restaurants? ... (resutoran...) ...bars? ... (baa) ...sites to see? ... (mimono...) Please show me on the map. (chizu de sashite kudasai) street (michi) Turn left. (Hidari e magatte kudasai.) Turn right. (Migi e magatte kudasai.) left (hidari) right (migi) straight ahead (massugu) towards the _____ _____ (e mukatte) past the _____ _____ (no saki) before the _____ _____ (no mae)

Watch for the _____. _____ (ga mejirushi desu) intersection (ksaten) north (kita) south (minami) east (higashi) west (nishi) uphill (nobori), also used for trains heading towards Tokyo downhill (kudari), also used for trains coming from Tokyo Taxi Taxi! ! (Taxi!) Take me to _____, please. _____ (_____ made onegai shimasu.) How much does it cost to get to _____? _____ ? (_____ made ikura desuka) Take me there, please. (soko made onegai shimasu.)

XV. Do you have any rooms available? ? (Aiteru heya arimasuka?) How much is a room for one person/two people? /? (Hitori/futari-y no heya wa ikura desuka?) Is the room Japanese/Western style? / (Washitsu/yshitsu desuka?) Does the room come with... ... ? (Heya wa ___ tsuki desuka?) ...bedsheets? ... (beddo no shiitsu...) ...a bathroom? (furoba...) ...a telephone? (denwa...) ...a TV? ? (terebi...) May I see the room first? ? (heya o mitemo ii desuka?) Do you have anything quieter? []? (motto [shizukana] heya arimasuka?) ...bigger? (hiroi) ...cleaner? (kirei na) ...cheaper? (yasui) OK, I'll take it. (hai, kore de ii desu.) I will stay for _____ night(s). _____ (____ ban tomarimasu.)

Do you know another place to stay? ? (hoka no yado wa gozonji desuka?) Do you have [a safe?] []? ([kinko] arimasuka?) ...lockers? ...? (rokkaa (locker) Is breakfast/supper included? /? (chshoku/yshoku wa tsukimasuka?) What time is breakfast/supper? /? (chshoku/yshoku wa nanji desuka?) Please clean my room. (heya o sji shite kudasai) Please wake me at _____. _____ (____ ni okoshite kudasai.) I want to check out. (chekku auto (check out) desu.)

XVI. Do you accept American/Australian/Canadian dollars? // (Amerika/sutoraria/kanada doru wa tsukae masuka?) Do you accept British pounds? (igirisu pondo wa tsukaemasuka?) Do you accept credit cards? (kurejitto kaado (credit card) wa tsukaemasuka?) Can you change money for me? (okane rygae dekimasuka?) Where can I get money changed? (okane wa doko de rygae dekimasuka?) Can you change a traveler's check for me? ((traveler's check) rygae dekimasuka?) Where can I get a traveler's check changed? ((traveler's check) wa doko de rygae dekimasuka?) What is the exchange rate? (kawase reeto wa ikura desu ka?) Where is an automatic teller machine (ATM)? ATM (ATM wa doko ni arimasuka?)

XVII. A table for one person/two people, please. / (hitori/futari desu) Please bring a menu. (menu o kudasai.) Can I look in the kitchen? (chriba o mite mo ii desu ka?) Is there a house specialty? (O-susume wa arimasuka?) Is there a local specialty? (Kono hen no meibutsu wa arimasuka? Please choose for me. (O-makase shimasu.) I'm a vegetarian. (Bejitarian desu.) I don't eat pork. (Butaniku wa dame desu.) I don't eat beef. (Gyniku wa dame desu.) I don't eat raw fish. (Nama no sakana wa dame desu.) Please do not use too much oil. (Abura o hikaete kudasai.) fixed-price meal (teishoku) la carte (ippinryri) breakfast (chshoku) lunch (chshoku)

light meal/snack (keishoku) supper (yshoku) Please bring _____. _____ (_____ o kudasai.) I want a dish containing _____. _____ (____ ga haitteru mono o kudasai.) chicken (toriniku) beef (gyniku) fish (sakana) ham (hamu) sausage (sseeji) cheese (chiizu) eggs (tamago) salad (sarada) (fresh) vegetables () ( (nama) yasai) (fresh) fruit () ( (nama) kudamono) bread (pan)

toast (tsuto) noodles (menrui) pasta (pasta) rice (gohan) beans (mame) May I have a glass/cup of _____? _____ (____ o ippai kudasai.) May I have a bottle of _____? _____ (_____ o ippon kudasai.) coffee (khii) green tea (o-cha) black tea (kcha) juice (kaj) water (mizu) beer (biiru) red/white wine / (aka/shiro wain) Do you have _____? _____ ? (_____ wa arimasuka?)

chopsticks (o-hashi) fork (fku) spoon (supn) salt (shio) black pepper (kosh) soy sauce (shyu) ashtray (haizara) Excuse me, waiter? (getting attention of server) (sumimasen) (when starting a meal) (itadakimasu) It was delicious. (when finishing a meal) (Go-chis-sama deshita.) Please clear the plates. (Osara o sagete kudasai.) The check, please. (O-kanjo onegai shimasu.)

XVIII. Do you serve alcohol? ? (O-sake arimasuka?) Is there table service? ? (Tburu sbisu arimasuka?) A beer/two beers, please. /(Biiru ippai/nihai kudasai.) A glass of red/white wine, please. /(Aka/shiro wain ippai kudasai.) A mug (of beer), please. (Biiru no jokki kudasai.) A bottle, please. . (Bin kudasai.) _____ (hard liquor) and _____ (mixer), please. _____ _____ (_____ to _____ kudasai.) sake (nihonshu) Japanese liquor (shch) whiskey (uisukii) vodka (wokka) rum (ramu) water (mizu) club soda (sda) tonic water (tonikku ut)

orange juice (orenji jsu) cola (soda) (kra) with ice (onzarokku) Do you have any bar snacks? ? (o-tsumami arimasuka?) One more, please. (M hitotsu kudasai.) Another round, please. (Minna ni onaji mono o ippai zutsu kudasai.) When is closing time? ? (Heiten wa nanji desuka?)

XIX. Do you have this in my size? (Watashi no saizu de arimasuka?) How much is this? (Ikura desuka?) That's too expensive. (Takasugimasu.) Would you take _____? _____ (_____ wa d desuka?) expensive (takai) cheap (yasui)

I can't afford it. (Sonna-ni o-kane wa motte imasen.) I don't want it. (Iranai desu.) You're cheating me. (Damashiteru n da.) Use with caution! I'm not interested. (Kymi nai desu.) OK, I'll take it. (Hai, sore ni shimasu.) Can I have a bag? (Fukuro moratte mo ii desuka?) Do you ship (overseas)? (Kaigai e hass dekimasuka?) I need... ___ (____ ga hoshii desu.) ...toothpaste. (hamigaki) ...a toothbrush. (ha-burashi) ...tampons. (tanpon) ...soap. (sekken) ...shampoo. (shanp) ...pain reliever. (e.g., aspirin or ibuprofen) (chintszai) ...cold medicine. (kazegusuri)

...stomach medicine. (ichyaku) ...a razor. (kamisori) ...an umbrella. (kasa) ...sunblock lotion. (hiyakedome) ...a postcard. (hagaki) ...postage stamps. (kitte) ...batteries. (denchi) ...writing paper. (kami) ...a pen. (pen) ...English-language books. (eigo no hon) ...English-language magazines. (eigo no zasshi) ...an English-language newspaper. (eigo no shinbun) ...a Japanese-English dictionary. (waei jiten) ...an English-Japanese dictionary. (eiwa jiten)

XX. I want to rent a car. (rent-a-car onegaishimasu.) Can I get insurance? ? (hoken hairemasuka?) stop (on a street sign) (tomare) one way (ipp tsuk) caution (jok) no parking (chsha kinshi) speed limit (seigen sokudo) gas (petrol) station (gasorin sutando) petrol (gasorin) diesel / (keiyu / diizeru)

XXI. In Japan, you can legally be incarcerated for twenty-three (23) days before you are charged, but you do have the right to see a lawyer after the first 48 hours of detention. Note that if you sign a confession, you will be convicted. XXII. I haven't done anything (wrong). ()(Nani mo (warui koto) shitemasen.) It was a misunderstanding. (Gokai deshita.)

Where are you taking me? (Doko e tsurete yukuno desuka?) Am I under arrest? (Watashi wa taiho sareteruno desuka?) I am a citizen of ____. ____ (____ no kokumin desu.) I want to meet with the ____ embassy. ____ (____ taishikan to awasete kudasai.) I want to meet with a lawyer. (Bengoshi to awasete kudasai.) Can it be settled with a fine? (Bakkin de sumimasuka?) Note: You can say this to a traffic cop, but bribery is highly unlikely to work in Japan.

XXIII. It might happen that there is a need to express negative emotions towards others. Or it might happen that others do this to you. In those cases it is useful to understand some Japanese offensive words. Please use these with care. XXIV. Fool or idiot (baka) Fool or idiot, used in Kansai (aho) - writing unsure Doing something untimely (manuke) A slow person (noroma) Being bad at something (heta) Being very bad at something (hetakuso)

A stingy person (kechi) An old man (jijii) An old woman (babaa) Not being cool (dasai) Fussy or depressing (uzai) Creepy (kimoi) Drop dead! (kutabare) Get out of the way! (doke) Noisy! (urusai) XXV. These words are mostly used by young people

Japanese generally employs a subject-object-verb order, using particles to mark the grammatical functions of the words: watashi-ga hamburger-o taberu, "I-subject hamburger-object eat". It is common to omit subjects and even objects if these are clear from previous context. Verbs and adjectives conjugate by tense and politeness level, but not by person or number. There is no verb "to be" as such, but the polite copula desu can be used in most cases: John desu ("I am John"), Ringo desu ("This is an apple"), Akai desu ("It is red"), etc. Note that the exact meaning will depend on the implied subject! The good news is that Japanese has none of the following: gender, declensions or plurals. Nouns never conjugate and almost all verbs are regular.

Unlike most western languages, Japanese has an extensive grammatical system to express politeness and formality. Since most relationships are not equal in Japanese society, one person typically has a higher position. This position is determined by a variety of factors including job, age, experience, or even psychological state (e.g., a person asking a favour tends to do so politely). The person in the lower position is expected to use a polite form of speech, whereas the other might use a more plain form. Strangers will also speak to each other politely. Japanese children rarely use polite speech until they are teens, at which point they are expected to begin speaking in a more adult manner. See uchi-soto Whereas teineigo is commonly an inflectional system, sonkeigo and kenjgo often employ many special honorific and humble alternate verbs: iku "to go" becomes ikimasu in polite form, but is replaced by irassharu in honorific speech and mairu in humble speech. The difference between honorific and humble speech is particularly pronounced in the Japanese language. Humble language is used to talk about oneself or one's own group (company, family) whilst honorific language is mostly used when describing the interlocutor and his/her group. For example, the -san suffix ("Mr" or "Ms") is an example of honorific language. It is not used to talk about oneself or when talking about someone from one's company to an external person, since the company is the speaker's "group". When speaking directly to one's superior in one's company or when speaking with other employees within one's company about a superior, a Japanese person will use vocabulary and inflections of the honorific register to refer to the ingroup superior and his or her speech and actions. When speaking to a person from another company (i.e., a member of an out-group), however, a Japanese person will use the plain or the humble register to refer to the speech and actions of his or her own in-group superiors. In short, the register used in Japanese to refer to the person, speech, or actions of any particular individual varies depending on the relationship (either in-group or out-group) between the speaker and listener, as well as depending on the relative status of the speaker, listener, and third-person referents. For this reason, the Japanese system for explicit indication of social register is known as a system of "relative honorifics." This stands in stark contrast to the Korean system of

"absolute honorifics," in which the same register is used to refer to a particular individual (e.g. one's father, one's company president, etc.) in any context regardless of the relationship between the speaker and interlocutor. Thus, polite Korean speech can sound very presumptuous when translated verbatim into Japanese, as in Korean it is acceptable and normal to say things like "Our Mr. Company-President..." when communicating with a member of an out-group, which would be very inappropriate in a Japanese social context. Most nouns in the Japanese language may be made polite by the addition of o- or go- as a prefix. o- is generally used for words of native Japanese origin, whereas go- is affixed to words of Chinese derivation. In some cases, the prefix has become a fixed part of the word, and is included even in regular speech, such as gohan 'cooked rice; meal.' Such a construction often indicates deference to either the item's owner or to the object itself. For example, the word tomodachi 'friend,' would become o-tomodachi when referring to the friend of someone of higher status (though mothers often use this form to refer to their children's friends). On the other hand, a polite female speaker may sometimes refer to mizu 'water' as o-mizu merely to show politeness; this contrasts with the more abrupt speech of rude men (though men may also use very polite forms when speaking to superiors). See Gender differences in spoken Japanese. Most Japanese people employ politeness to indicate a lack of familiarity. That is, they use polite forms for new acquaintances, but if a relationship becomes more intimate, they no longer use them. This occurs regardless of age, social class, or gender.

The original language of Japan, or at least the original language of a certain population that was ancestral to a significant portion of the historical and present Japanese nation, was the so-called yamato kotoba ( or , i.e. "Yamato words", which in scholarly contexts is sometimes referred to as wa-go ( or , i.e. the "Wa language"). In addition to words from this original language, present-day Japanese includes a great number of words that were either borrowed from Chinese or constructed from Chinese roots following Chinese patterns. These words, known as kango, entered the language from the fifth century onwards via contact with Chinese culture, both directly and through the Korean peninsula. According to some estimates, Chinese-based words comprise as much as seventy percent of the total vocabulary of the modern Japanese language and form as much as thirty to forty percent of words used in speech. Like Latin-derived words in English, kango words typically are perceived as somewhat formal or academic compared to equivalent Yamato words. Indeed, it is generally fair to say that an English word derived from Latin/French roots typically corresponds to a Sino-Japanese word in Japanese, whereas a simpler Anglo-Saxon word would best be translated by a Yamato equivalent. A much smaller number of words has been borrowed from Korean and Ainu. Japan has also borrowed a number of words from other languages, particularly ones of European extraction, which are called gairaigo. This began with borrowings from Portuguese in the 16th century,

followed by borrowing from Dutch during Japan's long isolation of the Edo period. With the Meiji Restoration and the reopening of Japan in the 19th century, borrowing occurred from German, French and English. Currently, words of English origin are the most commonly borrowed. In the Meiji era, the Japanese also coined many neologisms using Chinese roots and morphology to translate Western concepts. The Chinese and Koreans imported many of these pseudo-Chinese words into Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese via their kanji characters in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For example, seiji ("politics"), and kagaku ("chemistry") are words derived from Chinese roots that were first created and used by the Japanese, and only later borrowed into Chinese and other East Asian languages. As a result, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese share a large common corpus of vocabulary in the same way a large number of Greek- and Latin-derived words are shared among modern European languages, although many academic words formed from such roots were certainly coined by native speakers of other languages, such as English. In the past few decades, wasei-eigo (made-in-Japan English) has become a prominent phenomenon. Words such as wanpataan (< one + pattern, "to be in a rut", "to have a one-track mind") and sukinshippu (< skin + -ship, "physical contact"), although coined by compounding English roots, are nonsensical in a non-Japanese context. A small number of such words have been borrowed back into English. Additionally, many native Japanese words have become commonplace in English, due to the popularity of many Japanese cultural exports. Words such as sushi, judo, karate, sumo, karaoke, origami, tsunami, samurai, haiku, ninja, sayonara, rickshaw (from jinrikisha), futon, and many others have become part of the English language. See list of English words of Japanese origin for more.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- McMaster Icao Aviation EnglishDocument208 paginiMcMaster Icao Aviation Englishkggsmxb5ywÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cot1 Lesson Exemplar Grade 10 Week 5Document3 paginiCot1 Lesson Exemplar Grade 10 Week 5Ginelyn MaralitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Headway Elementary Unit 5Document72 paginiHeadway Elementary Unit 5Trần Thuỷ50% (2)

- InformatikaDocument4 paginiInformatikaMeisi MahdalenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CD Social Night (January 21) - StoryDocument6 paginiCD Social Night (January 21) - StorykoscakLukaÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Syntax 2 - Representinf Sentence StructureDocument14 paginiEnglish Syntax 2 - Representinf Sentence StructureArafiqIsmailÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bridge Month Programme English (R2) - 240402 - 205400Document17 paginiBridge Month Programme English (R2) - 240402 - 205400shivamruni324Încă nu există evaluări

- Grammar 1. TensesDocument9 paginiGrammar 1. TensesHapu LeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Olmec (Mande) Loan Words in The Mayan, Mixe-Zoque and Taino LanguagesDocument29 paginiOlmec (Mande) Loan Words in The Mayan, Mixe-Zoque and Taino LanguagesAdemário HotepÎncă nu există evaluări

- LinkDocument2 paginiLinkMitchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quick Guide To GREP Codes in Adobe InDesign-newDocument26 paginiQuick Guide To GREP Codes in Adobe InDesign-newMark NagashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading Comprehension PracticeDocument10 paginiReading Comprehension PracticeMomi BearFruitsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 0 Week 3 - Gerunds and InfinitivesDocument19 pagini0 Week 3 - Gerunds and Infinitivesmuhd firdaus0% (2)

- ADJECTIVEDocument1 paginăADJECTIVEbuddhakhunÎncă nu există evaluări

- MarsyaDocument48 paginiMarsyawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 - Confusables For StudentsDocument64 pagini6 - Confusables For Studentsmenna.ashmony.123Încă nu există evaluări

- Grammar Book-29Document59 paginiGrammar Book-29mauricioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modul Bahasa Inggris Semester 2 Kelas XDocument29 paginiModul Bahasa Inggris Semester 2 Kelas Xwidi antaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compilation of Assessment Tools in Hum 3 (Readings in Philippine History)Document3 paginiCompilation of Assessment Tools in Hum 3 (Readings in Philippine History)Tea AnnÎncă nu există evaluări

- EXERCISE 9: Drawing Conclusions From Implied InformationDocument1 paginăEXERCISE 9: Drawing Conclusions From Implied InformationLailyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test KL 7 3 Mujori I 1 Grupi ADocument2 paginiTest KL 7 3 Mujori I 1 Grupi ADorinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contemporary Theories in Cognitive Linguistics Power PointDocument5 paginiContemporary Theories in Cognitive Linguistics Power PointMajaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engle ZaDocument38 paginiEngle ZaAlexandru ProboteanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morphophonemic Variation Among Kinamayo Dialects - A Case StudyDocument18 paginiMorphophonemic Variation Among Kinamayo Dialects - A Case StudyAlfeo OriginalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Question Tags: (Made by Carmen Luisa)Document9 paginiQuestion Tags: (Made by Carmen Luisa)Co YiskāhÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Irregular Verbs: Infinitive Past Past Participle SpanishDocument3 paginiList of Irregular Verbs: Infinitive Past Past Participle SpanishCecilia HernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Issues of LingDocument190 paginiIssues of Lingდავით იაკობიძეÎncă nu există evaluări

- Actividad de Inglés de Recuperación PDFDocument3 paginiActividad de Inglés de Recuperación PDFMaritza CarbonellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samgroup: Unli Vocab Now LearningDocument20 paginiSamgroup: Unli Vocab Now LearningBrixter MangalindanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Infosys 6th August SlotDocument92 paginiInfosys 6th August SlotP. Manoj B4Încă nu există evaluări