Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Radikulopati

Încărcat de

Riyanti Januani AnggiaDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Radikulopati

Încărcat de

Riyanti Januani AnggiaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Lumbosacral Radiculopathy Article Last Updated: Apr 27, 2006 References Author: Gerard A Malanga, MD, Associate Professor,

Department of Physical Medici ne and Rehabilitation, New Jersey Medical School; Director of Pain Management, U niversity of Medicine and Dentistry at New Jersey, Overlook Hospital; Director o f Sports Medicine, Mountainside Hospital Gerard A Malanga is a member of the following medical societies: American Academ y of Pain Medicine, American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Am erican College of Sports Medicine, North American Spine Society, and Physiatric Association for Spine, Sports and Occupational Rehabilitation Coauthor(s): Charles J Buttaci, DO, PT, Staff Physician, Kessler Institute for R ehabilitation, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey; Mariam Rubbani, MD, Consulting Staff, Dep artment of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Union County Orthopedic Group Editors: Andrew D Perron, MD, Residency Director, Department of Emergency Medici ne, Maine Medical Center; Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD, Senior Pharmacy Edito r, eMedicine; Henry T Goitz, MD, Chief, Sports Medicine, Department of Orthopaed ic Surgery, Associate Professor, Medical College of Ohio; Jon Whitehurst, MD, Co nsulting Staff, Rockford Orthopedic Associates; William Jay Bryan, MD, Clinical Professor, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Baylor University College of Medici ne Author and Editor Disclosure Background Some of the major causes of acute and chronic low back pain (LBP) are associated with radiculopathy. Radiculopathy is not a cause of back pain; rather, nerve ro ot impingement, disk herniation, facet arthropathy, and other conditions are the cause of the back pain. Lumbosacral radiculopathy, like other forms of radiculo pathy, results from nerve root impingement and/or inflammation that has progress ed enough to cause neurologic symptoms in the areas supplied by the affected ner ve root(s). Frequency United States Lumbosacral radiculopathy occurs in 2% of the population. Of these cases, 10-25% develop symptoms that persist for more than 6 weeks. Functional Anatomy The anatomy of the lumbar epidural space is the key to understanding the mechani sm of radiculopathic pain. The sinuvertebral nerves innervate structures in this space. These nerves originate distal to the dorsal root ganglion; they then run back through the intervertebral foramen to supply the arteries, venous plexi, a nd lymphatics. At the inner aspect of the intervertebral foramen, these nerves d ivide into ascending and descending branches that freely communicate with corres ponding branches from the segment above, from the segment below, and from the op posite side. The sinuvertebral nerve supplies the posterior longitudinal ligament, superficia l annulus fibrosus, epidural blood vessels, anterior dura mater, dural sleeve, a nd posterior vertebral periosteum. The 2 structures capable of transmitting neur onal impulses resulting in the experience of pain are the sinuvertebral nerve an d the nerve root. The posterior rami of the spinal nerves supply the apophyseal joints above and below the nerve and the paraspinous muscles at multiple levels. Herniation of the intervertebral disk can cause impingement of the above neurona l structures, thus causing pain. The presence of disk material in the epidural s pace is thought to initially result in direct toxic injury to the nerve root by chemical mediation and then exacerbation of the intraneural and extraneural swel

ling, which results in venous congestion and conduction block. Notably, the size of the disk herniation has not been found to be related to the severity of pain . Pain also is believed to be mediated by inflammatory mechanisms involving substa nces such as phospholipase A2, nitric oxide, and prostaglandin E. These mediator s are all found in the nucleus pulposus itself. Phospholipase A2 has been found in high concentrations in lumbar herniated disks. This substance acts on cell me mbranes to release arachidonic acid, a precursor to other prostaglandins and leu kotrienes that further advance the inflammatory cascade. Additionally, leukotrie nes B4 and the substance thromboxane B2 have been found to have direct nocicepti ve stimulatory roles. From a biomechanical standpoint, the lumbar intervertebral disks are highly susc eptible to herniation because they are exposed to tremendous forces, principally by the magnification of forces that results from the lever effect of the human arm in lifting; the forces generated by the upper trunk mechanics with rotation, flexion/extension, and side-bending on the disks below; and by vertical forces associated with the upright position. Because each intervertebral disk is a flui d system, hydraulic pressure is generated whenever a load is placed on the axial skeleton. Hydraulic pressure mechanisms multiply the force on the annulus fibro sus of the intervertebral disk to make it 3-5 times that exerted on the axial sk eleton. Sport Specific Biomechanics Dancers are prone to both acute and chronic back problems. These back problems d evelop secondary to the combination of 2 factors that are required in most dance routines: extreme physical flexibility and exposure of the spine to extremes of range of motion. Additionally, female dancers are predisposed to disk herniatio n secondary to the positioning required in certain movements, such as pas de deu x (in which excess lumbar lordosis is present), as well as the large jumps that they often perform. Golfers are also very susceptible to disk disease and radiculopathy because of t he repetitive torsional motion used in the sport. The golf swing can produce up to an estimated 7500 N of compressive force across L3-L4. Competitive weight lif ters and football linemen have been noted to experience even larger compressive loads.

CLINICAL Section 3 of 11 Authors and Editors Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Medication Follow-up Miscellaneous Multimedia References History The onset of symptoms is often sudden and includes LBP. Some patients state the preexisting back pain disappears when the leg pain begins. Sitting, coughing, or sneezing may exacerbate the pain. The pain travels from th e buttock down to the posterior or posterolateral leg to the ankle or foot. Radiculopathy in roots L1-L3 refers pain to the anterior aspect of the thigh and

typically does not radiate below the knee, but these levels are affected in onl y 5% of all herniations. When obtaining a patient's history, be alert for any red flags (ie, indicators o f medical conditions that usually do not resolve on their own without management ). These red flags may imply a more complicated condition that requires further workup (eg, tumor, infection). The presence of fever, weight loss, or chills req uires a thorough evaluation. Patient age is also a factor when looking for other possible causes. Those younger than 20 years and those older than 50 years are at increased risk for more malignant causes of pain (eg, tumor, infection). Physical A comprehensive physical examination of a patient with acute LBP should include an in-depth evaluation of the neurological and musculoskeletal systems. The neurological examination should always include an evaluation of sensation, s trength, and reflexes in the lower extremities. This portion of the examination allows the examiner to detect sensory or motor deficits that may be consistent w ith an associated radiculopathy or cauda equina syndrome. Often, an assessment o f the L5 reflex, medial hamstrings, is helpful. Provocative maneuvers, such as straight leg raising, may provide evidence of inc reased dural tension indicating underlying nerve root pathology. Attempts at pai n centralization through postural changes, ie, lumbar extension, may suggest a d iskogenic etiology for pain and also may assist in determining the success of fu ture treatment strategies. The musculoskeletal evaluation should include an assessment of the lower extremi ty joints, as pain referral patterns may be confused with focal peripheral invol vement. For example, a patient with anterior thigh and knee pain may actually ha ve a degenerative hip condition and not an upper lumbar radiculopathy. By assess ing lower extremity flexibility, hip rotation, muscular balance, and ligamentous stability, the evaluating physician might be alerted to the patient's predispos ition toward an acute LBP episode. Combining the findings of the history and physical examination increases the ove rall predictive value of the evaluation process. Further diagnostic studies are indicated only upon the completion of a thorough history and physical examinatio n and the establishment of a differential diagnosis. DIFFERENTIALS Section 4 of 11 Authors and Editors Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Medication Follow-up Miscellaneous Multimedia References Lumbosacral Disc Injuries Thoracic Disc Injuries Trochanteric Bursitis Other Problems to be Considered Spinal stenosis Cauda equina syndrome Demyelinating conditions Extraspinal nerve entrapment

Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve entrapment (sensory only) Spondylolysis WORKUP Section 5 of 11 Authors and Editors Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Medication Follow-up Miscellaneous Multimedia References Imaging Studies Plain radiographs o Plain radiographs are the most common type of imaging used in the workup of patients with LBP. However, radiographs are not routinely necessary for most episodes of acute LBP, especially within the first 6 weeks after the onset of s ymptoms. Radiographs generally have been overused. Additionally, they often are unremarkable in patients with radiculopathy secondary to herniated nucleus pulpo sus. o The main purpose of plain radiographs is to detect serious underlying st ructural pathologic conditions. Many changes seen on radiographs of symptomatic patients also are seen in radiographs of asymptomatic patients. o Selective criteria can be used to improve the usefulness of plain radiog raphs. ? Radiographs generally are not recommended in the first month of symptoms if there are no red flags. ? Oblique views are rarely indicated, as they increase both cost and radia tion exposure. MRI o MRI has demonstrated excellent sensitivity in the diagnosis of lumbar di sk herniation and is considered the imaging study of choice for nerve root impin gement. However, this preference is tempered by the prevalence of abnormal findi ngs in asymptomatic subjects. o ? The use of MRI should be reserved for selected patients. Immediate MRI of the spine may be indicated in patients with progressive neurologic deficits or cauda equina syndrome, in patients with a presentation s uggestive of malignancy, in patients with a known history or high risk of malign ancy, or to evaluate a possible inflammatory disease or infection. ? MRIs are not necessary in all patients with examination findings consist ent with a radiculopathy, and, in fact, they generally should be reserved for th ose cases in which the imaging results are likely to guide treatment. ? When physical examination and electrodiagnostic findings do not indicate exact levels of pathology in a patient in need of a selective nerve root block, MRI may help the physician determine the exact level of pathology (see Electrod iagnosis).

? In the absence of red flags, many patients (even those with a classic ra diculopathy) can and should be managed without an MRI, especially if they are no t being considered for surgery or injections. Some clinicians reserve MRI for th ose patients not responding to treatment as expected. ? The addition of gadolinium is not necessary in most cases unless the pat ient has had a previous surgery or there is interest in the enhancing qualities of a previously observed lesion. CT scanning: Scanning of the lumbar spine provides superior anatomic imaging of the osseous structures of the spine and good resolution for disk herniation. The sensitivity of CT scan without myelography for detecting disk herniation is inf erior to that of MRI. As with MRI, there can be a significant number of positive findings in the asymptomatic population. Myelogram o A myelogram involves penetration of the subarachnoid space. Myelograms g enerally are not indicated in the evaluation of acute LBP. o Generally, the myelogram is reserved as a preoperative test, often perfo rmed in conjunction with a CT scan. This provides a detailed anatomic picture, p articularly of the spinal osseous elements, and can be used to correlate examina tion findings and assist in preoperative planning. o Myelograms are rarely used in the nonoperative evaluation of patients wi th acute LBP, except in cases in which the clinical picture supports a progressi ve neurologic deficit and the MRI and electromyography are nondiagnostic. Diskography o Diskography is rarely necessary in the evaluation of acute LBP and certa inly is not recommended within the first 3 months of treatment. Diskography can be helpful in patients who have not responded to a well-coordinated rehabilitati on program or who have normal or equivocal MRI findings. In such cases, it may h ave some benefit in localizing a symptomatic disk as the etiology of nonradicula r back pain. o A positive diskogram must include a concordant pain response, which incl udes reproduction of symptoms upon injection of a symptomatic disk, a nonpainful response upon injection of control disks, and observed annular pathology on pos tdiskography CT scan, if used. o Diskography most often is used prior to contemplating surgical fusion fo r unremitting pain due to a symptomatic internal disk disruption. Some authors h ave found diskography followed by CT scan to be a more precise technique that ma y delineate diskovertebral pathology with sensitivities similar to or better tha n MRI and CT scan/myelography. o Diskography must be used with care as a significant percentage of indivi duals with positive diskography findings improve without surgery. In addition, i ndividuals with underlying psychological issues tend to overreport pain during d iskographic injection. Diskographic injection still remains to be the only quasi -objective provocative test for disk-mediated pain. CT diskography recently has received attention because it may be a good predictor of outcome following lumba r fusion for patients with intractable back pain. Other Tests Electrodiagnosis o Electrodiagnostic studies, including nerve conduction studies, needle el ectromyography, and somatosensory evoked potential studies, should be considered an extension of the history and physical examination and not merely a substitut

e for detailed neurologic and musculoskeletal examinations. o These studies are helpful in evaluating patients with limb pain when the diagnosis remains unclear (eg, peroneal neuropathy vs radiculopathy). They also are helpful in excluding other causes of sensory and motor disturbances, such a s peripheral neuropathy and motor neuron disease. Additionally, they can provide useful prognostic information by quantifying the extent and acuity of axonal in volvement in radiculopathies. o Performing late responses, such as the H-reflex, can provide valuable in formation regarding the proximal nerve/nerve root involvement. The H-reflex is b oth a sensitive and specific marker for involvement of the S1 root and will be p rolonged from time of symptom onset. o F waves, which also are used to detect abnormalities in the proximal por tion of nerves, are too nonspecific to be clinically useful in the setting of ra diculopathy. o Electrodiagnostic testing usually is not necessary in a clear-cut radicu lopathy or in patients with isolated mechanical low back symptoms. Furthermore, these studies do not assess the smaller myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers , which typically are responsible for pain transmission. o If the patient has had previous episodes of radicular symptoms or prior spinal surgery, it may be useful both diagnostically and from a medicolegal stan dpoint to perform initial electrodiagnostic studies as soon as possible after th e appearance of new symptoms, so as to differentiate later developments from pre existing disease. o Specific electrodiagnostic studies are as follows: ? Nerve conduction studies: Distal peripheral motor and sensory nerve cond uction studies often are normal in a single-level radiculopathy. ? Needle electromyography: This technique offers a high diagnostic yield. Timing is important, and the study should be performed less than 4-6 months (but >18-21 d) from onset. ? Somatosensory evoked potential studies: These studies are of limited val ue in the assessment of acute LBP and radiculopathy. They are not indicated unle ss neurologic signs and symptoms are suggestive of pathology that would indicate involvement of the somatosensory pathways. Procedures See Other Tests. TREATMENT Section 6 of 11 Authors and Editors Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Medication Follow-up Miscellaneous Multimedia References Acute Phase Rehabilitation Program

Physical Therapy A second method, commonly referred to as "back school," involves teaching the pa tient back protection techniques (eg, proper lifting, posture awareness). A lumb ar stabilization program is another useful method physical therapists may incorp orate for patients with LBP. With this method, the patient is instructed in vari ous techniques to control his or her back pain while working on strengthening th e stabilizing muscles of the lumbar spine. This is actually a combination of dif ferent techniques and may involve the McKenzie program at some point. Core strengthening is advocated by many rehabilitation specialists as a means of improving muscular control around the lumbar spine to maintain functional stabi lity. The contents of the core include the abdominals anteriorly, paraspinals an d gluteals posteriorly, the diaphragm as the roof, and the pelvic floor and hip girdle musculature as the floor. A typical program consists of a series of grade d exercises that promote movement awareness and motor relearning in addition to strengthening. Soft tissue modalities are also usually incorporated into a back pain program. T hese modalities involve specific manual techniques, myofascial release, or massa ge to improve the soft tissue component of a patient's pain. The use of lumbar traction has been a preferred method of treating lumbar disk p roblems for a long time. Lumbar traction requires approximately 1.5 times the pe rson s body weight to develop distraction of the vertebral bodies. This can be cum bersome and time consuming; furthermore, most individuals find it to be difficul t to tolerate. Vertebral axial decompression (VAX-D), a newer method to cause this distraction of the vertebral bodies, probably represents a more technical version of tractio n. Currently, no evidence is present in the peer-reviewed literature to support this form of treatment. No significant difference in outcome has been demonstrat ed with traction versus sham traction; however, greater morbidity has been demon strated in the traction group. A limited amount of evidence supports its use. Gi ven the effectiveness of more active treatments, traction generally is not recom mended in the treatment of acute LBP. The above techniques also may be used during the recovery phase, with a lifelong home exercise program forming part of the maintenance phase. Surgical Intervention Most sources agree on the urgent and definite indications for surgical intervent ion in lumbar radiculopathy (eg, significant and progressive motor deficits, cau da equina syndrome with bowel and bladder dysfunction, severe and progressive mo tor deficits). The 5 surgical treatment options are as follows: Simple diskectomy Diskectomy plus fusion Chemonucleolysis Percutaneous diskectomy Microdiskectomy At present, 90% of patients who have surgery for lumbar disk herniation undergo diskectomy alone, although the number of spinal fusion procedures has greatly in creased. Additionally, the complication rate of simple diskectomy is reported at less than 1%. Other Treatment Epidural steroid injections are a modality that appears promising, despite a pau city of well-designed trials of their efficacy. In a 1999 review, Abrams reporte d that only 13 controlled randomized trials had been published on the use of epi dural steroid injections for back pain. In 2000, a study by Lutz demonstrated a success rate of 75.4% using selective ne rve blocks in conjunction with oral medications and physical therapy. Other inve stigators also found similar benefits from the procedure. The growing consensus is that this treatment is most effective in acute cases (3-6 mo post onset).

In a 2005 review, DePalma found level III (moderate) evidence supporting transfo raminal epidural steroid injections in the treatment of lumbosacral radiculopath y. Six trials were analyzed in the review, and no significant complications were reported. Most clinicians agree that a transforaminal approach to the epidural space is pr eferred to an interlaminar or caudal approach. This technique routinely delivers medication to the anterior epidural space. Recovery Phase Rehabilitation Program Physical Therapy In the recovery phase, patients should gradually progress with their physical th erapy program to continue to decrease pain and focus on functional stabilization and back safety techniques. By the end of this phase, patients should be indepe ndent with an appropriate home exercise program. Other Treatment (Injection, manipulation, etc.) Manipulation/mobilization Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of manipulation and soft tissue m obilization in the treatment of acute LBP. These studies have demonstrated that manual medicine techniques can relieve acute pain and reduce symptoms in the ini tial stages of treatment. The best effects are noted during the initial 1-4 week s of treatment. The initial manipulation prescription should be performed once per week in conju nction with the exercise program. The incorporation of patient-activated treatme nt, termed muscle energy, can be performed up to 2-3 times per week and should b e performed in conjunction with an active exercise program. Regularly scheduled follow-up visits are necessary to monitor for change in symp toms and/or physical examination findings. Clear-cut goals of treatment should be established at the onset of treatment. A lack of improvement after 3-4 treatments should result in a discontinuation of m anipulation and a reassessment. Manual medicine treatment may be incorporated into the initial treatment of acut e LBP to facilitate the patient s active exercise program. Treating practitioners should be aware of the contraindications for manipulation, especially manipulati on under anesthesia, which has been demonstrated to be a high-risk practice. Whi le superior patient satisfaction levels have been demonstrated among those patie nts receiving manipulation-based care, there is no support for maintenance treat ment once the acute pain episode has resolved. Maintenance Phase Rehabilitation Program Physical Therapy Once discharged from physical therapy, the patient will be expected to continue their home exercise program on a regular basis, with the understanding that the management of lumbar radiculopathy is a long-term process. MEDICATION Section 7 of 11 Authors and Editors Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Medication Follow-up Miscellaneous Multimedia References

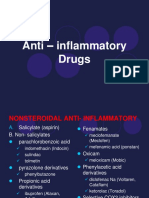

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the mainstay of initial treatm ent. With use of all NSAIDs, elderly patients should be monitored for gastrointe stinal and renal toxicity. Pain control with acetaminophen or a suitable narcoti c may be more appropriate for elderly patients. Muscle relaxants are not first-line agents, but they may be considered for patie nts experiencing significant spasms. No studies have documented that these medic ations change the natural history of the disease. Because these medications may cause drowsiness and dry mouth, it may be useful to recommend that they be taken at least 2 hours before bedtime. Drug Category: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents Have analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic activities. Their mechanism o f action is not known, but they may inhibit cyclo-oxygenase activity and prostag landin synthesis. Other mechanisms may exist as well, such as inhibition of leuk otriene synthesis, lysosomal enzyme release, lipoxygenase activity, neutrophil a ggregation, and various cell membrane functions. Drug Name Diclofenac (Voltaren, Cataflam) Description Inhibits prostaglandin synthesis by decreasing activity of enzym e cyclo-oxygenase, which in turn decreases formation of prostaglandin precursors . Adult Dose 50 mg PO bid/tid Pediatric Dose Not established Contraindications Documented hypersensitivity; do not administer into CNS; do not administer to those at high risk of bleeding or to patients with peptic ulcer disease, recent GI bleeding or perforation, or renal insufficiency Interactions Coadministration with aspirin increases risk of inducing serious NSAID-related side effects; probenecid may increase concentrations and, possibl y, toxicity of NSAIDs; may decrease effect of hydralazine, captopril, and beta-b lockers; may decrease diuretic effects of furosemide and thiazides; may increase PT when taking anticoagulants (instruct patients to watch for signs of bleeding ); may increase risk of methotrexate toxicity; phenytoin levels may be increased when administered concurrently Pregnancy B - Usually safe but benefits must outweigh the risks. Precautions Category D in third trimester of pregnancy; acute renal insuffic iency, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, interstitial nephritis, and renal papillary n ecrosis may occur; increases risk of acute renal failure in patients with preexi sting renal disease or compromised renal perfusion; low white blood cell counts occur rarely and usually return to normal in ongoing therapy; discontinuation of therapy may be necessary if leukopenia, granulocytopenia, or thrombocytopenia p ersists Drug Name Naproxen (Aleve, Naprelan, Naprosyn, Anaprox) Description For relief of mild to moderate pain. Inhibits inflammatory react ions and pain by decreasing activity of cyclo-oxygenase, which results in a decr ease of prostaglandin synthesis. Adult Dose 250-500 mg PO bid Pediatric Dose <13 kg: 2.5 mL susp PO bid 14-25 kg: 5 mL/dose 26-38 kg: 7.5 mL/dose Contraindications Documented hypersensitivity; peptic ulcer disease; recen t GI bleeding or perforation; renal insufficiency Interactions Coadministration with aspirin increases risk of inducing serious NSAID-related side effects; probenecid may increase concentrations and, possibl y, toxicity of NSAIDs; may decrease effect of hydralazine, captopril, and beta-b lockers; may decrease diuretic effects of furosemide and thiazides; may increase PT when taking anticoagulants (instruct patients to watch for signs of bleeding ); may increase risk of methotrexate toxicity; phenytoin levels may be increased when administered concurrently Pregnancy B - Usually safe but benefits must outweigh the risks. Precautions Category D in third trimester of pregnancy; acute renal insuffic iency, interstitial nephritis, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, and renal papillary n

ecrosis may occur; patients with preexisting renal disease or compromised renal perfusion risk acute renal failure; leukopenia occurs rarely, is transient, and usually returns to normal during therapy; persistent leukopenia, granulocytopeni a, or thrombocytopenia warrants further evaluation and may require discontinuati on of drug Drug Category: Muscle relaxants For radiculopathy with a significant component of spasm. Drug Name Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Description Skeletal-muscle relaxant that acts centrally and reduces motor a ctivity of tonic somatic origins influencing both alpha- and gamma-motor neurons . Structurally related to TCAs and thus carries some of the same liabilities. Adult Dose 10 mg PO tid initially; not to exceed 60 mg/d Pediatric Dose Not established Contraindications Documented hypersensitivity; have taken MAOIs within las t 14 d Interactions Coadministration with MAOIs and TCAs may increase toxicity; cycl obenzaprine may have additive effect when used concurrently with anticholinergic s; effects of alcohol, CNS depressants, and barbiturates may be enhanced with cy clobenzaprine Pregnancy B - Usually safe but benefits must outweigh the risks. Precautions Caution in angle closure glaucoma, and urinary hesitance Drug Category: Analgesics Pain control is essential to quality patient care. Analgesics ensure patient com fort and have sedating properties, which are beneficial for patients who are in pain. Drug Name Oxycodone (OxyContin) Description Indicated for the relief of moderate to severe pain. Adult Dose 10 mg PO bid initially Pediatric Dose Not established Contraindications Documented hypersensitivity; in patients with significan t history of respiratory depression and whose respiratory functions are not bein g closely monitored; severe bronchial asthma; hypercarbia, paralytic ileus Interactions Phenothiazines may antagonize analgesic effects; MAOIs, general anesthesia, CNS depressants, and TCAs may increase toxicity Pregnancy B - Usually safe but benefits must outweigh the risks. Precautions Pregnancy category D if used for prolonged periods or if given i n high doses; caution in COPD, emphysema, and renal insufficiency Drug Name Oxycodone and acetaminophen (Percocet, Tylox, Roxicet, Roxilox) Description Drug combination indicated for the relief of moderate to severe pain. Adult Dose 1-2 tab or cap PO q4-6h prn pain Pediatric Dose 0.05-0.15 mg/kg/dose oxycodone PO; not to exceed 5 mg/dose of ox ycodone q4-6h prn Contraindications Documented hypersensitivity Interactions Phenothiazines may decrease analgesic effects of this medication ; toxicity increases with coadministration of CNS depressants or TCAs Pregnancy C - Safety for use during pregnancy has not been established. Precautions Duration of action may increase in elderly persons; be aware of total daily dose of acetaminophen patient is receiving; do not exceed 4000 mg/d; higher doses may cause liver toxicity FOLLOW-UP Section 8 of 11 Authors and Editors Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Medication

Follow-up Miscellaneous Multimedia References Education The patient needs to have an understanding of the likely etiology of their pain. The examination findings of patients with acute LBP often can be suggestive, th ough no clinical or historical findings have been found to significantly correla te with confirmed pain generators. Review the basic anatomy and biomechanics of the spine with the patient. Discuss the etiology of the patient's symptoms. Also discuss the treatment plan, includ ing a description of recommended imaging studies, medications, injections, and t herapeutic exercises. Review proper posture, the biomechanics of the spine in ac tivities of daily living, and simple methods to reduce symptoms. These early and simple instructions enable the patient to become an active participant in the t reatment as he or she progresses to a more comprehensive home exercise program. The patient must understand the lifelong commitment to the program because the s ingle most important risk factor for future episodes of back pain is a previous episode. Patient education should be considered an ongoing process that must con tinually be refined. Directed education should continue until the patient is ind ependent in his or her maintenance exercise program. For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicine's Bone Health Center. Also, see eMedicine's patient education article Back Pain. MISCELLANEOUS Section 9 of 11 Authors and Editors Introduction Clinical Differentials Workup Treatment Medication Follow-up Miscellaneous Multimedia References Medical/Legal Pitfalls Failure to recognize more serious medical conditions that may feature back pain o All red flag symptoms must be pursued for an etiology. Symptoms such as fever, weight loss, or chills may represent a more ominous condition, such as tu mor, and must be dealt with expeditiously to yield the best chance of improving the patient's health, if not to save the patient's life. o Failure to be aware of and to act on these red flags could have serious medicolegal consequences. o Failure to recognize cauda equina syndrome or significant motor deficits could also have legal implications.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Backpacking First Aid KitDocument2 paginiBackpacking First Aid KitAndrewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piroxicam GelDocument6 paginiPiroxicam GelClosed WayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Locating and Appraising Systematic ReviewsDocument7 paginiLocating and Appraising Systematic ReviewsSofía SciglianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drug 1Document2 paginiDrug 1Nicholas TagleÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 Anti - Inflammatory Drugs, Anti-Gout DrugsDocument15 pagini5 Anti - Inflammatory Drugs, Anti-Gout DrugsAudrey Beatrice ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ankle Sprains ManagementDocument68 paginiAnkle Sprains ManagementWalter CordobaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study 9Document11 paginiCase Study 9Angel MayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab Report - CarbohydratesDocument7 paginiLab Report - CarbohydratesMICAH SOQUIATÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drug StudyDocument11 paginiDrug StudyRose AnnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balance Wheel Vs JuvenileDocument17 paginiBalance Wheel Vs JuvenileWiljohn de la CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pharmacology Online 2011Document11 paginiPharmacology Online 2011evanyllaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drug StudyDocument8 paginiDrug StudyJason AvellanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antiinflammatory Drugs: Toya AriawanDocument27 paginiAntiinflammatory Drugs: Toya Ariawanlast100% (1)

- AINS CaseDocument11 paginiAINS CaseMarilena TarcaÎncă nu există evaluări

- IndometacinDocument47 paginiIndometacinSava1988Încă nu există evaluări

- Anti EmeticsDocument112 paginiAnti Emeticsjoel david knda mjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Most Common Food-Drug InteractionsDocument17 paginiMost Common Food-Drug InteractionsNazi AwanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Puerperio FisiológicoDocument47 paginiPuerperio Fisiológicosamuel de limaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modern Dravya GunaDocument21 paginiModern Dravya GunaAvinash Perfectt0% (2)

- Vocabular CuvinteDocument10 paginiVocabular CuvinteAlina-elena Micevski-ignatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Farmacologia em Cães GeriátricosDocument12 paginiFarmacologia em Cães GeriátricosRafaela RodriguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- UMT 02 - PT 652 Pharmacology in Rehabilitation - 01.13.2021.2020Document14 paginiUMT 02 - PT 652 Pharmacology in Rehabilitation - 01.13.2021.2020Nabil KhatibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sport, Health and Drugs: A Critical Re-Examination of Some Key Issues and ProblemsDocument20 paginiSport, Health and Drugs: A Critical Re-Examination of Some Key Issues and ProblemsFaridah Haji YusofÎncă nu există evaluări

- Periodontal Complications of Prescription and Recreational DDocument12 paginiPeriodontal Complications of Prescription and Recreational DRuxandra MurariuÎncă nu există evaluări

- DiclofenacDocument22 paginiDiclofenacintan kusumaningtyasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acetylsalicilic Acid 250mg + Paracetamol 250mg + Caffeine 65mg (Acamol Focus, Exidol, Exedrin, Paramol Target)Document6 paginiAcetylsalicilic Acid 250mg + Paracetamol 250mg + Caffeine 65mg (Acamol Focus, Exidol, Exedrin, Paramol Target)asdwasdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anti-Rheumatoid Arthritis DrugsDocument57 paginiAnti-Rheumatoid Arthritis Drugsapi-306036754Încă nu există evaluări

- Pericardial EffusionDocument26 paginiPericardial EffusionjsenocÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maqui en Cancer de ColonDocument10 paginiMaqui en Cancer de ColonsadalvaryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diagnosis and Management of Acute Low Back Pain - American Family PhysicianDocument7 paginiDiagnosis and Management of Acute Low Back Pain - American Family Physicianmagdalena novianaÎncă nu există evaluări