Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

T. S. Eliot's Forgotten "Poet of Lines," Nathaniel Wanley

Încărcat de

issamagicianDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

T. S. Eliot's Forgotten "Poet of Lines," Nathaniel Wanley

Încărcat de

issamagicianDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

56

ANQ

T. S. Eliots Forgotten Poet of Lines, Nathaniel Wanley

Although T. S. Eliot considered him a minor poet, we need not presume his claim that Henry Vaughan was too much a poet of lines rather than poems to have been entirely derogatory (Varieties 168). However moderate his estimation of Vaughan may have been, it certainly did not prevent him from stealing (as he claimed poets must) those few good lines and weaving them into his own verse.1 With his penchant for allusion and quotation, Eliot made great use of many such one-liners, so it should come as little surprise to find that those written by one of Vaughans literary students should subtly infiltrate his poetry as well. Scholars have known about the Reverend Nathaniel Wanleys (163480) gargantuan prose compilation of historical oddities and anecdotes, The Wonders of the Little World (1678), and its influence on Ash-Wednesday (1930) for some time now, but none have yet remarked on the distinctive characteristics of Wanleys verse that would have initially caught Eliots attention and that exerted a unique pressure not only on Ash-Wednesday, but on his later work as well, including the Ariel poem Marina (1930), the verse drama The Family Reunion (1939), and Four Quartets (1942).2 I would like to linger a moment longer over the haunting lines of this forgotten influence and to suggest several places in which it seems that Eliot allowed himself to do the same. Although not as pervasive an influence as Donnes or Crashaws, Wanleys verse nonetheless played a distinct role in Eliots education in the poetics of devotion and in the spiritual significance of passive suffering. Eliot first encountered the reverends work in December 1925 when he wrote a review (as yet uncollected in any published edition) of Oliver Eltons Essays and Studies by Members of the English Association (1925)a compilation that includes L. C. Martins essay on Wanley, A Forgotten Poet of the Seventeenth Centuryfor the Times Literary Supplement (Wanley). Martins essay relates the neglected history and formerly-disputed authorship of Wanleys work and proceeds to reprint, for the first time, a group of his poems themselves. Martin applauds the new sampling of Wanleys verse, claiming it by no means unworthy of our golden age of divine poetry (5). For his part, Eliot concedes that the poems are pleasing but disparagingly suggests that the best of them are almost as good as Vaughan in his less inspired moments (Wanley). Despite this Janus-faced compliment (not dissimilar to his claim about Vaughan), Eliot admits a particular attraction to Wanleys The Resurrection and quotes it at length in the review, claiming for it a greater individuality than any of the devotional lyrics (Wanley). Martins essay on Wanley could not have reached Eliot at a more propi-

Spring 2006, Vol. 19, No. 2

57

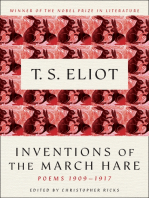

tious time. Immersed in the metaphysical poets in preparation for his upcoming Clark lectures (1926), Eliot had just finished a review of Mario Prazs study of John Donne and Richard Crashaw. During the next nine months, he would engage the work of Robert Southwell and Lancelot Andrewes as well, two other religious thinkers to whom he afforded a unique place in the spiritual movement of sensibility that he would eventually attempt to recapture in Ash-Wednesday.3 With religion and devotional literature foremost in his mind, Eliot must have been quick to recognize a kindred devotional and artistic spirit in this forgotten poet of lines. Even if, in Eliots eyes, Wanleys other devotional lyrics were lacking, it seems likely that the ominous approach of death the porter in The Deceite (included after The Resurrection in Martins essay) would have resonated with the author of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1917) and his snickering eternal Footman (Martin 13; Eliot, The Complete Poems and Plays [hereafter CPP] 6). No less likely would Wanleys description of his hardened heart in his The SighThere is more life in stocks and stonehave recalled to Eliot the disillusionment of his own interior journeys, just three years before, [a]mongst the rock and stony landscape of The Waste Land (1922; Martin 15; Eliot, CPP 47). But these minor shades of resemblance were soon eclipsed by another of Eliots growing concerns, one which undoubtedly drew him closer to the reverend: Mr. Wanley, by the way, he remarks almost incidentally, was apparently much interested in the problems of resurrection (Wanley). Wanleys bizarre account of the partial resurrection, however, is only one aspect of many that he confronted involving problems of resurrection and that made him so attractive to Eliot. A year before the Times review and several years after his reportedly shocking comment to Ezra Pound at Excideuil (I am afraid of the life after death), Eliot had also revealed his persistent preoccupation with the unique state of the soul dispossessed in his introduction to Paul Valrys Le Serpent (1924; Brief Introduction 13).4 With his thoughts on dispossession and the afterlife, several lines from Wanleys The Invitation could not have failed to reverberate with Eliots own growing fear of severance from the divine: shall thy people bee so deare / to thee no more, Wanley inquires of God, is not heavn to Earth as neare / as heretofore? (Martin 6). In an early untitled poem (Do I know how I feel?) included in Inventions of the March Hare (1996), Eliot had embodied this fear of dispossession in a grotesque scenario featuring an etherized patient and a malevolent surgeon who approaches to dismember his paralyzed body [w]ith chemicals and knife to investigate the cause of death that was also the cause of the life (80). Turning to Wanleys poems three months after his own harrowing experience with chemicals and knife in 1925,5 Eliot would have been immediately struck by the protagonist of Feares, who entertains a similar analogue for dispossession, imagining himself torturd on a rack / Till my distended heartstrings crack, or fleyd alive

58

ANQ

to have the knife / Not cutt but saw the thread of life (Martin 16). Wanleys metaphors for passive, purgative suffering stuck with Eliot, and he returned to them years later in East Coker (1940) to transform them under a transcendent light, when he envisions another etherized patient at the hands of a Christological surgeon who plies the steel / That questions the distempered part (CPP 127). He had not forgotten this frightening scenario even by 1949, when he invoked it in The Cocktail Party, once again as a physical correlative to a state of spiritual paralysis (Cuda 40811). But in 1925, Eliot was still only beginning to cultivate an imaginative capacity for human suffering and its spiritual significance, and he found in Wanleys litany of horrific feares the same immense passive strength to endure suffering that attracted him to Baudelaire as well. Such suffering as Baudelaires, he claims with a certainty only further strengthened by his encounter with Wanleys purgatorial vision, implies the possibility of a positive state of beatitude (Selected Essays 423). With Wanleys lines still fresh in his mind, Eliot began work on AshWednesday, returning again to the problems of resurrection that so occupied the reverends imagination. In the passage of The Resurrection included in the Times review, Wanleys vivid vision of his own death and the devouring of his fleshWhat if this flesh of mine be made the prey / Of scaly Pirates Caniballs at seaechoes Eliots earlier figures for physical and spiritual decay, including Phlebas, whose corpse the sea current [p]icked [. . .] in whispers, and Prufrock with his head brought in upon a platter (Martin 12; CPP 46, 6). In Ash-Wednesday, however, Eliot integrates Wanleys vision of his own devoured flesh with the three Dantescan leopards, who fed to satiety / On my legs my heart my liver and that which had been contained / In the hollow round of my skull (CPP 61). In addition, although the scattered and reunited bonesthe bones sang, scattered and shining / We are glad to be scattered (CPP 62)in part 2 of Ash-Wednesday invoke Ezekiel 37.110, they also rely on the passage that Eliot had quoted from The Resurrection, in which Wanleys speaker wonders if his own scattred dust and bones shall ever find their way back together:

Can death be faithfull or the Grave be just Or shall my tombe restore my scattred dust Shall evry haire find out its proper pore And crumbled bones be joined as before[?] (Martin 12)

Ezekiel influences Eliots exhortationProphesy to the wind, to the wind onlybut lurking in the background is also Wanleys rendering of the whistling winds that partake in the bodys scattering and dismemberment, convey[ing] / Each atome to a quite contrary way (CPP 62; Martin 12). In The Deceite, he had encountered Wanleys self-indictment of his

Spring 2006, Vol. 19, No. 2

59

False heart, which zealously performs its spiritual duties but refuses to surrender its last, cupidinous desire:

False heart that dost pretend to thrust Through flames and Floods and death to Rest Yet darst not quitt one bosome lust [. . .] (Martin 13)

Eliot revisits these lines when he confronts the deceitful desires of his own heart in Ash-Wednesday, climbing the purgatorial stairs to thrust himself beyond the distractions of the devil of the stairs who wears / The deceitful face of hope and of despair and an erotic bosome lust of his own, represented by Priapus and his seductive garden lute (CPP 63). Finally, Wanleys desperate exclamationMy soule is famishd and I dye / unlesse thou heareis still firmly in Eliots mind as he concludes Ash-Wednesday, spiritually famished in a desert / Of drouth and crying: Suffer me not to be separated / And let my cry come unto Thee (Martin 6; CPP 6667). Not long after Ash-Wednesday, Eliot would find occasion to reassemble from his memory another of Wanleys scattered lines that he had quoted in the reviewShall long-unpractisd pulses learne to beate / Victorious rottennesse a loud retreatewhen he asks in Marina (1930) if the joyous discovery of another newfound pulseWhat is this [. . .] pulse in the arm, less strong and strongerwill cast away a spiritual decay not unlike Wanleys rottennesse, namely, the sty of contentment and the ecstasy of the animals, meaning / Death (Martin 12; CPP 72). And later, in The Family Reunion (1939), he returns to Wanleys fearful question about the problems of resurrectionShall living Sepulchres give up there [sic] dead[?]when his protagonist, Harry Lord Monchensey, asks: Do not the ghosts of the drowned / Return to land in the spring? / Do the dead want to return? (Martin 12; CPP 251). Eliots continued interest in this forgotten poet of lines extends even beyond these ghastly visions of dismemberment and resurrection. When the narrator of Wanleys The Deceite proclaims his desire to join the blessed in their heavenly place, even if it proves to be beguirt with feircer flames / Then those that circle soules in hell, could Eliot have failed to associate these lines with those spoken in the Purgatorio by his cherished Arnaut Daniel (and quoted repeatedly throughout his own work), the shade who willingly plunges into flames just as fierce as those that consume the sinners of the Inferno (Martin 13)? Wanleys narrator, also, wonders if the working of a subtile flame shall embrace his soul and dissolve this frame / To ashes, or elsewhere if this brest / Is with a holy flame possest, and Eliot recalls these lines when, pondering the [a]sh on an old mans sleeve, he suggests in Little Gidding (1942) that our only hope [. . .] Lies in the choice of pyre or pyre / To be redeemed from fire by fire (Martin 12; CPP 139, 144). Finally, Eliot revisits Wanleys vision of the bright Angells bathing in full streames who beckon the narrator of The Ressurection with the shrill

60

ANQ

sound / Of heavens summons when, in The Family Reunion, Harry heeds the summons of his newfound angelic guides and leaves the stage with a oneliner of his own: I must follow the bright angels (Martin 12; CPP 281).6 Even if Eliot never again explicitly addressed Wanleys work (which is absent from the Clark Lectures), an imagination as expansive as his undoubtedly made ample room for the reverends lines to submerge and continue germinating somewhere in its depths, only to resurface transfigured and recombined with Dante, Ezekiel, and his own earlier phantasmagoria (Eliot, Three Voices 28). In fact, we would not be amiss to suggest, in the words Eliot used to describe Coleridge, that Wanleys lines sank to the depths of his imagination, were saturated, transformed there [. . .] and brought up into daylight again (Use of Poetry 146). By bringing this forgotten Phlebas into the daylight again, alongside the other metaphysical and devotional poets who influenced Eliot more overtly, we familiarize ourselves with yet another element of his education in the purgative character of devotional poetry and the spiritual significance of suffering. As Eliot himself claims elsewhere: If the likeness exists, then it is valuable to understand the poetry of the seventeenth century, in order that we may understand that of our own time and understand ourselves (Varieties 43). ANTHONY J. CUDA Emory University Copyright 2006 Heldref Publications

NOTES 1. For Eliots observations regarding Vaughan, see his review of Edmund Blundens On the Poems of Henry Vaughan: Characteristics and Imitations (Silurist). With regard to his literary debts to Vaughan, the great ring of light that he quotes in the Clark lectures from Vaughans The World (1650) resonates with similar luminous rings in his own Portrait of a Lady and Rhapsody on a Windy Night (1917), and Schuchard notes the inclusion of a line from Vaughans The Night (1650) in Mr. Eliots Sunday Morning Service (1919) (Varieties 168). 2. Scholarly attention to Wanleys influence on Ash-Wednesday has been hitherto entirely limited to his description of the superstitious phenomenon known as the partial resurrection. See Bush (138) and Southam (225). 3. For Eliots claim that Southwell occupies a place in an important movement of sensibility, see his review of Christobel M. Hoods The Book of Robert Southwell (1926; Author). His essay on Lancelot Andrewes appeared in September 1926 (Lancelot), and the year before, he reviewed Mario Prazs Secentismo e marinismo in Inghilterra: John DonneRichard Crashaw (1925) for the Times Literary Supplement, as well (Italian Critic). 4. For Eliots comment to Pound during their visit to Excideuil in 1919, see Schuchard (119). 5. In September 1925, Eliot was anesthetized with ether at the outset of an unexpectedly complex operation on his jaw. In a letter written soon afterward to Richard Cobden-Sanderson, he reveals the disturbing effects of the ether, claiming to have stumbled out of the operation in the mid-afternoon uttering curses at God (Letter).

Spring 2006, Vol. 19, No. 2

61

6. See also Wanleys The Sabbath: Harke what a solemne noise of praise / the people raise / o let it rise / Till the loud Eccho touch the skies / Till the Bright Angells shall agree / To beare a part in th Harmonye (Martin 14). WORKS CITED Bush, Ronald. T. S. Eliot: A Study in Character and Style. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1983. Cuda, Anthony. T. S. Eliots Etherized Patient. Twentieth-Century Literature 50 (2004): 394420. Eliot, T. S. The Author of The Burning Babe. Times Literary Supplement 29 July 1926: 508. . A Brief Introduction to the Method of Paul Valry. Le Serpent. By Paul Valry. Trans. Mark Wardle. London: R. Cobden-Sanderson, 1924. 715. . The Complete Poems and Plays, 19091950. New York: Harcourt, 1967. . Inventions of the March Hare, Poems 19091917. Ed. Christopher Ricks. New York: Harcourt, 1996. . An Italian Critic on Donne and Crashaw. Times Literary Supplement 17 Dec. 1925: 878. . Lancelot Andrewes. Times Literary Supplement 23 Sept. 1926: 62122. . Letter to Richard Cobden-Sanderson. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. . Selected Essays. 3rd ed. London: Faber and Faber, 1972. . The Silurist. Dial Sept. 1927: 25963. . The Three Voices of Poetry. New York: Cambridge UP, 1954. . The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism. London: Faber and Faber, 1933. . The Varieties of Metaphysical Poetry. Ed. Ronald Schuchard. New York: Harcourt, 1993. . Wanley and Chapman. Times Literary Supplement 31 Dec. 1925: 907. Martin, L. C. A Forgotten Poet of the Seventeenth Century. Essays and Studies by Members of the English Association. Ed. Oliver Elton. Oxford: Clarendon, 1925. 531. Schuchard, Ronald. Eliots Dark Angel: Intersections of Life and Art. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Southam, B. C. A Guide to the Selected Poems of T. S. Eliot. 6th ed. New York: Harcourt, 1968.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Unit 12 T.S. ELIOT "PRELUDES"Document17 paginiUnit 12 T.S. ELIOT "PRELUDES"Ashique ElahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life Studies: Robert LowellDocument18 paginiLife Studies: Robert LowellLeaMaroni100% (2)

- POEMS Eliot, TS The Waste Land (1922) Analysis by 25 CriticsDocument24 paginiPOEMS Eliot, TS The Waste Land (1922) Analysis by 25 CriticsSabina QeleposhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shrek - Fairy Tale Shrek PianoDocument2 paginiShrek - Fairy Tale Shrek PianoBomsos100% (1)

- Of Being Numerous - George OppenDocument27 paginiOf Being Numerous - George OppenFenetus Maíats100% (1)

- Puritan AnxietyDocument24 paginiPuritan AnxietyMadan KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module B Essay - T.S EliotDocument3 paginiModule B Essay - T.S EliotChristopher Cheung0% (1)

- The Radical Poetics of Robert CreeleyDocument14 paginiThe Radical Poetics of Robert CreeleyAnonymous 0Y3E2O5mAÎncă nu există evaluări

- T.S Eliot (1888 - 1965)Document6 paginiT.S Eliot (1888 - 1965)Aswathi KÎncă nu există evaluări

- TS Eliot Journey of The MagiDocument12 paginiTS Eliot Journey of The Magijmorg0605100% (3)

- Kallocain: PlotDocument110 paginiKallocain: PlotArkinAardvark100% (2)

- Emmanuel Levinas - God, Death, and TimeDocument308 paginiEmmanuel Levinas - God, Death, and Timeissamagician100% (3)

- Dove Descending: A Journey Into T.S. Eliot's Four QuartetsDe la EverandDove Descending: A Journey Into T.S. Eliot's Four QuartetsEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (8)

- Zuber, Rene - Who Are You Monsieur GurdjieffDocument88 paginiZuber, Rene - Who Are You Monsieur Gurdjieffaviesh100% (2)

- The Poem Adonais My 11Document16 paginiThe Poem Adonais My 11Marwan AbdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- About The Fallen Ones, Also Known As NephilimDocument3 paginiAbout The Fallen Ones, Also Known As NephilimBranislav DjordjevicÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Was Modernism-Harry LevinDocument23 paginiWhat Was Modernism-Harry Levinissamagician100% (1)

- Bohubrihi by Humayun AhmedDocument132 paginiBohubrihi by Humayun Ahmedapi-26170322100% (2)

- Assessment1 crb006 n8018286Document44 paginiAssessment1 crb006 n8018286api-358690568Încă nu există evaluări

- Fahrenheit 451 Unit Plan PDFDocument2 paginiFahrenheit 451 Unit Plan PDFAmormioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noun Worksheet For Class 6 With Answers 1Document9 paginiNoun Worksheet For Class 6 With Answers 1Sujatha S67% (3)

- RahuDocument4 paginiRahugirish shastriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Empty Silences - T.S. Eliot and Eugenio Montale PDFDocument25 paginiEmpty Silences - T.S. Eliot and Eugenio Montale PDFRadekÎncă nu există evaluări

- THW Waste LandDocument99 paginiTHW Waste Landandrijana91Încă nu există evaluări

- DocumentDocument2 paginiDocumentErika CalistroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thomas Stearns EliotDocument26 paginiThomas Stearns Eliotanzala noorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The West LandDocument2 paginiThe West LandMaría Cristina Arenas AyalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- T. S. Eliot - Waste Land AnalysisDocument2 paginiT. S. Eliot - Waste Land AnalysisSolve et CoagulaÎncă nu există evaluări

- T. S. Eliot'S Modernism in Thewaste Land: Asha F. SolomonDocument4 paginiT. S. Eliot'S Modernism in Thewaste Land: Asha F. SolomonAmm ÃrÎncă nu există evaluări

- EliotDocument7 paginiEliotLinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- EliotDocument7 paginiEliotLinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Duke University Press, Hofstra University Twentieth Century LiteratureDocument28 paginiDuke University Press, Hofstra University Twentieth Century LiteraturejeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drama 1Document11 paginiDrama 1Bushra MumtazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement On Ts EliotDocument8 paginiThesis Statement On Ts EliotWriteMyBiologyPaperCanada100% (4)

- Yeats and ModernismDocument21 paginiYeats and ModernismDana KiosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- T.S Eliot and Ezra PoundDocument7 paginiT.S Eliot and Ezra PoundEYAJABEURÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allusions WastelandDocument1 paginăAllusions WastelandDina HinnawiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Department of English National University of Modern Languages, IslamabadDocument4 paginiDepartment of English National University of Modern Languages, IslamabadDanyal KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Waste Land Source 12Document41 paginiWaste Land Source 12Guelan LuarcaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wolfe PDFDocument4 paginiWolfe PDFAsaf AbramovichÎncă nu există evaluări

- Examination of Influences On EliotDocument2 paginiExamination of Influences On EliotsafdarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catalyzing PrufrockDocument18 paginiCatalyzing Prufrockapi-238626560Încă nu există evaluări

- Eliot StillpointDocument14 paginiEliot StillpointVerónica ChiodoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Austin, T. S. Eliot's Theory of Dissociation (1962)Document5 paginiAustin, T. S. Eliot's Theory of Dissociation (1962)bartalore4269Încă nu există evaluări

- The Hollow MenDocument6 paginiThe Hollow MenIkram TadjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modern Civilization As Reflected in Modern Poetry-Daily SunDocument2 paginiModern Civilization As Reflected in Modern Poetry-Daily SunDeea Paris-PopaÎncă nu există evaluări

- T.S. Eliot's Linguistic UniverseDocument13 paginiT.S. Eliot's Linguistic UniverseCristina AlexandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- T S EliotDocument3 paginiT S EliotMarga SuciuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection T. S. EliotDocument9 paginiReflection T. S. EliotRafael EnriquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allusion EliotDocument2 paginiAllusion EliotMehedee2084100% (2)

- T.S Eliot Life and WorksDocument3 paginiT.S Eliot Life and WorksLavenzel YbanezÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Romantic Poet in The Victorian PeriodDocument12 paginiA Romantic Poet in The Victorian PeriodAlexandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- TS EliotDocument5 paginiTS EliotGabriela BuicanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tradition and The Individual Talent - ANALYSIS2Document8 paginiTradition and The Individual Talent - ANALYSIS2Swarnav MisraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preludes Means: StructureDocument9 paginiPreludes Means: StructureDebasis ChakrabortyÎncă nu există evaluări

- T S Eliot and Bertrand Russell A CriticaDocument3 paginiT S Eliot and Bertrand Russell A CriticaEiman Farouq MoharremÎncă nu există evaluări

- Florence Van Leer Earle Coates: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument5 paginiFlorence Van Leer Earle Coates: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchKliv MediaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dissociation of Sensibilities AnswerDocument5 paginiDissociation of Sensibilities AnswerMohona BhattacharjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Four QuartetsDocument18 paginiFour Quartetsema_mirela88Încă nu există evaluări

- Eliot Nietzsche and The Problem of HistoryDocument13 paginiEliot Nietzsche and The Problem of Historyaaaa2010Încă nu există evaluări

- Ts Eliot Thesis StatementsDocument7 paginiTs Eliot Thesis StatementsBuyCheapEssayOmaha100% (2)

- 2020 The Journey of The Magi Selected AnaylsisDocument14 pagini2020 The Journey of The Magi Selected AnaylsisHeyqueenÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is The Structure of The PoemDocument7 paginiWhat Is The Structure of The PoemLina100% (1)

- Representation of Women in Eliot's "A Game of Chess"Document13 paginiRepresentation of Women in Eliot's "A Game of Chess"ammagraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock (Introduction) (Encyclopaedia)Document10 paginiThe Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock (Introduction) (Encyclopaedia)Ritankar RoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- AMP Research Essay ProperDocument21 paginiAMP Research Essay ProperSteph ReidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 2Document11 paginiUnit 2kirti vithaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- EliotDocument2 paginiEliotGianluca FranchiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lboutang, Journal Manager, 1 BrennaDocument8 paginiLboutang, Journal Manager, 1 BrennaRox VazquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zizek-The Undergrowth of EnjoymentDocument23 paginiZizek-The Undergrowth of EnjoymentgideonstargraveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Irving Babbitt, The Moral ImaginationDocument15 paginiIrving Babbitt, The Moral ImaginationJorge VargasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zizek-The Undergrowth of EnjoymentDocument23 paginiZizek-The Undergrowth of EnjoymentgideonstargraveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Voices of The Marginalized in Tunisian Narrative - Sonia S'hiriDocument18 paginiVoices of The Marginalized in Tunisian Narrative - Sonia S'hiriissamagicianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assistanat Speech (August 2012)Document9 paginiAssistanat Speech (August 2012)issamagicianÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 C095 E63 D 01Document17 pagini6 C095 E63 D 01issamagicianÎncă nu există evaluări

- 435516Document10 pagini435516issamagicianÎncă nu există evaluări

- News & Notes: T. S. Eliot Soc Let YDocument4 paginiNews & Notes: T. S. Eliot Soc Let YissamagicianÎncă nu există evaluări

- News & Notes: T. S. Eliot Soc Let YDocument4 paginiNews & Notes: T. S. Eliot Soc Let YissamagicianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Communication European Journal Of: Heritage Museum Encoding and Decoding The People: Circuits of Communication at A LocalDocument19 paginiCommunication European Journal Of: Heritage Museum Encoding and Decoding The People: Circuits of Communication at A LocalissamagicianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Years: P-27088-Bt28-D2 P-27088-Bt28-D2Document1 paginăYears: P-27088-Bt28-D2 P-27088-Bt28-D2api-282945255Încă nu există evaluări

- Dungeons and Downloads: Collecting Tabletop Fantasy Role-Playing Games in The Age of Downloadable PdfsDocument11 paginiDungeons and Downloads: Collecting Tabletop Fantasy Role-Playing Games in The Age of Downloadable PdfsAli ZubairÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Mind Upper Intermediate Unit 6 CEFR ChecklistDocument1 paginăOpen Mind Upper Intermediate Unit 6 CEFR ChecklistOmar MohamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hamlet CharactersDocument3 paginiHamlet Characterspamela aroniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sasken Sample Verbal Placement Paper Level1Document6 paginiSasken Sample Verbal Placement Paper Level1placementpapersampleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Giao An Anh 9 k1Document104 paginiGiao An Anh 9 k1Dâu TâyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Merchant of VeniceDocument23 paginiThe Merchant of VeniceShalu MandiyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizal MakamisaDocument1 paginăRizal MakamisaAbigail SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jane Austen's Limited RangeDocument2 paginiJane Austen's Limited RangeIffatM.Ali100% (2)

- Curs-Fonetica Varianta-ID 2013Document169 paginiCurs-Fonetica Varianta-ID 2013Amalia SirbuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poetic Architecture by Kent Johnson With Photography by Geoffrey Gatza Book PreviewDocument24 paginiPoetic Architecture by Kent Johnson With Photography by Geoffrey Gatza Book PreviewBlazeVOX [books]Încă nu există evaluări

- I Love TheeDocument5 paginiI Love TheePrinithiavanee GanesanÎncă nu există evaluări

- GDC TestDocument3 paginiGDC TestGlenda De CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Black Eyed Peas - Lyrics AnalysisDocument3 paginiBlack Eyed Peas - Lyrics AnalysisVinnakota HarishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ghosh Letter To Administrators of Commonwealth Writers PrizeDocument2 paginiGhosh Letter To Administrators of Commonwealth Writers PrizeKaushik RayÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Origin and Development of English Novel: A Descriptive Literature ReviewDocument6 paginiThe Origin and Development of English Novel: A Descriptive Literature ReviewIJELS Research JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Diamond As Big As The RitzDocument2 paginiThe Diamond As Big As The RitzMatheus PerucciÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3rd Grade Scope and SequenceDocument30 pagini3rd Grade Scope and Sequencemeryem rhimÎncă nu există evaluări

- wuolah-free-TEATRO RENACENTISTA INGLÉSDocument14 paginiwuolah-free-TEATRO RENACENTISTA INGLÉSDiana Prieto VillafuertesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Listening Section UN Bahasa Inggris 2012Document4 paginiListening Section UN Bahasa Inggris 2012Regina TamaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kondralum KutramillaiDocument38 paginiKondralum KutramillaiKrishnaveni VasanthÎncă nu există evaluări