Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Credit Transactions Case Digest

Încărcat de

Mousy GamalloDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Credit Transactions Case Digest

Încărcat de

Mousy GamalloDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Pua v. Spouses Bautista CA-G.R. CV NO.

77418, August 11, 2006 Facts: Spouses Bautista contracted a loan with Anita Pua, petitioner, amounting to 1.02M with a stipulation on interest pegged at 20% per annum. After payment of some 450K plus, the respondents stopped making payments. Despite frequent demands from the petitioner, the spouses failed to send payment. The petitioner re-computed the loan amount at 2M to include thereof the accrued interests, and filed a complaint for collection of sum of money with the MTCwhich the lower court ruled in favor of the petitioner. The spouses then questioned before the Court the re-computed amount alleging that it is excessive and unconscionable. Issue: Could the interest rate being agreed upon by parties be considered as excessive? Held: No. Elementary is the rule that when the obligation is breached, and it consists in the payment of a sum of money, i.e., a loan or forbearance of money, the interest due should be that which may have been stipulated in writing. Here, the Bautistas agreed to a 20% interest rate per annum to be applied on top of their loan principal. The stipulated interest rate of 20% per annum was not excessive, iniquitous, unconscionable, or in any way exorbitant. There are already cases where the Supreme Court validated even a higher rate of stipulated interest. It is important to note that the Bautistas freely agreed on the rate of interest that would govern their contract of loan. Parties to a contract of loan like in any other contracts are essentially free to stipulate on the terms of their undertaking. If their debt increased considerably, it is because they had been in default for a long time. Applying the stipulated interest rate on the loan, the Court believes that re-computed amount of P1,889,829 is fairly reasonable considering that more than six years have passed since the last payment of the Bautistas was recorded. It is to be considered that the computation was made right in front of the Bautistas who could have easily protested if there was any mistake or irregularity in the procedure. Instead, the Bautistas again acknowledged the amount. Francisco v. Gregorio GR No. L-59519 July 20, 1982 Facts: Petitioner Francisco, through her daughter, agreed to lease a piece of land where a building should be constructed by the former. The contract provided, among others: the deposit to the account of the lessor-petitioner the amount of 150k representing 30K goodwill money and 120K advanced rental and a stipulation that in case the parties will not agree as to the terms and conditions of the final contract of lease, the pre-lease contract shall be declared null and void and the petitioner shall return the deposit plus legal interest. Before final occupancy, the petitioner declared the pre-lease contract null and void, leased the premises to another lessee and offered to return the 150K deposit. Private respondents refused to accept so that petitioner was prompted to make a consignation of the money

with the Court. Private respondents then filed a complaint, hence respondent judge ruled in their favor with an order to pay the amount of deposit plus compensatory interests. Issue: Is the petitioner liable for payment of interest despite tender of payment before demand? Held: No. The award for interests in an action for the recovery of a sum of money partakes of a nature of an award for damages. Thus, Article 2209 of the Civil Code provides: Art. 2209. If the obligation consists in the payment of a sum of money, and the debtor incurs in delay, the indemnity for damages, there being no stipulation to the contrary, shall be the payment of the interest agreed upon, and in the absence of stipulation, the legal interest, which is six percent per annum. Clearly, the indemnity for interest on a monetary obligation attaches only when the obligor incurs delay, that is, when he is in default, it being a fundamental principle of law that: Those obliged to deliver or to do something incur in delay from the time the obligee judicially or extrajudicially demands from them the fulfillment of their obligation. (Art. 1169, Civil Code.) In the case at bar, it is not disputed that no demands, judicial or extrajudicial, were made by private respondents on defendant Boiser (Francisco) for the return of the amount of P150,000.00. There could not have been any because of the nature of the action filed by private respondents, which is for specific performance. Hence, there is no delay of the latter's obligation, assuming that she be eventually required in the decision of the Court to return the same. Thus, no interest is due where there was tender of payment prior to any demand to pay or perform the agreed act. State Investment House, Inc. v. CA GR No. 90676 June 19, 1991 Facts: Private respondents Spouses Rafael & Refugia Aquino pledged certain shares of stock to petitioner to secure a loan. Prior to the execution of such pledge, respondents, agreed with the petitioner for the latter's purchase of receivables from Spouses Jose and Marcelina Aquino. Respondent spouses paid their loan partly from their own money and from the proceeds of a new loan secured by the same pledge. Upon maturity of the new loan, petitioner demanded payment. Respondents expressed willingness to pay requesting that upon payment the shares of stocks pledged be released. Petitioner denied the request on the ground that the loan extended to Jose & Marcelina had remained. Respondent sued the petitioner. The trial judge ruled in their favor. During execution, the petitioner refused to accept payment demanding that interests be paid. Issue: Are the respondents liable for payment of interest even without mora? If they are liable, on what rate should the interests be? Held: On the first issue, yes. The respondents may not be in default in view of their expressed willingness to pay the same upon demand and the refusal of the petitioner to accept. However, their tender of payment should have been properly consigned with the court. On the second issue, since respondent spouses were held not to have been in delay, they were properly liable only for the principal

of the loan and the stipulated regular or monetary interest of 17% per annum. They were not liable for penalty or compensatory interest, fixed by the promissory note in Account No. IF-82-0904-AA at two percent (2%) per month or twenty-four (24%) per annum. It must be stressed that the appropriate measure for damages in case of delay in discharging an obligation consisting of the payment of a sum or money, is the payment of penalty interest at the rate agreed upon; and in the absence of a stipulation of a particular rate of penalty interest, then the payment of additional interest at a rate equal to the regular monetary interest; and if no regular interest had been agreed upon, then payment of legal interest or six percent (6%)per annum, or in the case of loans or forbearances of money, 12 % per annum as provided for in Central Bank Circular No. 416. Reformina vs tumol jr. 139 SCRA 260 FACTS: A fire occurred burning the boat FB Pacita III and fishing gear of the Reforminas.Consequently, they filed an action for recovery of damages for injury to persons and loss of property.Judge Tomol, Jr awarded the Reforminas damages with legal interest from the filing of thecomplaint until paid. He further rendered that by legal interest meant 6% as provided for by Art 2209 CC.Reforminas contend that it should be 12% by virtue of Central Bank Circular No. 416.ISSUE: WON the legal interest is 6%HELD: YESRATIO: C.B. Circular 416 which took effect July 29, 1974 pursuant to PD 116 which amended Act 2655 (Usury Law) which raised the legal interest fro 6% to 12% applies only to forbearances of money, goodsor credit and court judgments. Such court judgment refers only to judgments in litigations involving loansor forbearance of any money, goods or credit.Any other kind of monetary judgment does not fall under the coverage of said law for it is notwithin the ambit of authority granted to the central Bank. Only the legislature can change the laws.In this case, the the decision of the judge is one rendered in an action for damages arising frominjury to persons and loss of property and does not involve a loan much less forbearance of any money,goods or credit. The law applicable is thus ART 2209 CC which states that: If the obligation consists in the payment of a sum of money and the debtor incurs in delay, theindemnity for damages there being no stipulation to the contrary shall be the payment of interest agreedupon, and in the absence of stipulation, the legal interest which is 6% per annum.Plana Concurring and Dissenting:Under Sec 1 a of Act 2655 as amended by PD 116, the authority of CB is to fix a maximum rateof interest on loans and not to prescribe a fixed interest rate.Such authority given to CB is absolute and unqualified and therefore the delegation of power to itis void

Canonisado vs or donee 149 SCRA 55 Spouses Cuyco v. Spouses Cuyco GR No. 168736 April 19, 2006 Facts: Spouses Feliciano & Adelina Cuyco, petitioners, obtained a loan of 1.5M at a rate of 18% interest per annum and secured by real estate mortgage over a parcel of land with improvements, from Spouses Renato & Filipina Cuyco, respondents. Subsequent loans were also obtained, however the contracts covering some of the loans were not expressed as to whether they were still covered by the same mortgage. Petitioners defaulted payments, so that the respondents sued for foreclosure and sale of the property to settle the obligations of the petitioners. RTC rendered judgment ordering the petitioners to

settle the amount of loans plus interests compounded, the interest of 18% shall also earn the legal interest of 12%. On appeal, CA affirmed RTC's decision as to interests but clarified that the mortgage could only cover those loans contracts that were expressly stating so, and that payment of the principal obligation 18% per annum shall discharge the property mortgage. Issue: 1. Are the courts correct in compounding the interests and adding a legal interest over the stipulated interest? 2. Should the subsequent loans be covered by the mortgage however absent the stipulations? 3. Shall payment of the principal plus the stipulated interest discharge the property mortgaged? Held: On the first issue, Yes, the courts did not erred in applying the rules in application of interest enunciated in Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc v. CA which states in paragraph 1, When an obligation is breached, and it consists in the payment of a sum of money, i.e., a loan or forbearance of money, the interest due should be that which may have been stipulated in writing.Furthermore, the interest due shall itself earn legal interest from the time it is judicially demanded. In the absence of stipulation, the rate of interest shall be 12% per annum to be computed from default, i.e., from judicial or extrajudicial demand under and subject to the provisions of Article 1169 of the Civil Code. Applying the rules in Eastern Shipping case, the Court laid down the follwoing formula: TOTAL AMOUNT DUE = [principal + interest + interest on interest] - partial payments made Interest = principal x 18 % per annum x no. of years from due date until finality of judgment Interest on interest = Interest computed as of the filing of the complaint (September 10, 1997) x 12% x no. of years until finality of judgment Total amount due as of the date of finality of judgment will earn an interest of 12% per annum until fully paid. On the 2nd issue, As a general rule, a mortgage liability is usually limited to the amount mentioned in the contract. An obligation is not secured by a mortgage unless it comes fairly within the terms of the mortgage contract. It is clear from a perusal of the aforequoted real estate mortgage that there is no stipulation that the mortgaged realty shall also secure future loans and advancements. Thus, what applies is the general rule above stated. On the last issue, no discharge of the mortgage until the satisfaction of the debt and other incidental costs. Section 2, Rule 68 of the Rules of Court provides that If upon the trial in such action (foreclosure for payment or sale) the court shall find the facts set forth in the complaint to be true, it shall ascertain the amount due to the plaintiff upon the mortgage debt or obligation, including interest and other charges as approved by the court, and costs, and shall render judgment for the sum so found due and order that the same be paid to the court or to the judgment obligee within a period of not less than

ninety (90) days nor more than one hundred twenty (120) days from the entry of judgment, and that in default of such payment the property shall be sold at public auction to satisfy the judgment. Phil. Airlines inc. vs ca 275 SCRA 621 FACTS: On 23 October 1988, Leovigildo A. Pantejo, then City Fiscal of Surigao City, boarded a PAL plane in Manila and disembarked in Cebu City where he was supposed to take his connecting flight to Surigao City. However, due to typhoon Osang, the connecting flight to Surigao City was cancelled. To accommodate the needs of its stranded passengers, PAL initially gave out cash assistance of P 100.00 and, the next day, P200.00, for their expected stay of 2 days in Cebu. Pantejo requested instead that he be billeted in a hotel at the PALs expense because he did not have cash with him at that time, but PAL refused. Thus, Pantejo was forced to seek and accept the generosity of a co-passenger, an engineer named Andoni Dumlao, and he shared a room with the latter at Sky View Hotel with the promise to pay his share of the expenses upon reaching Surigao. On 25 October 1988 when the flight for Surigao was resumed, Pantejo came to know that the hotel expenses of his co-passengers, one Superintendent Ernesto Gonzales and a certain Mrs. Gloria Rocha, an Auditor of the Philippine National Bank, were reimbursed by PAL. At this point, Pantejo informed Oscar Jereza, PALs Manager for Departure Services at Mactan Airport and who was in charge of cancelled flights, that he was going to sue the airline for discriminating against him. It was only then that Jereza offered to pay Pantejo P300.00 which, due to the ordeal and anguish he had undergone, the latter declined. Pantejo filed a suit for damages against PAL with the RTC of Surigao City which, after trial, rendered judgment, ordering PAL to pay Pantejo P300.00 for actual damages, P150,000.00 as moral damages, P100,000.00 as exemplary damages, P15,000.00 as attorneys fees, and 6% interest from the time of the filing of the complaint until said amounts shall have been fully paid, plus costs of suit. On appeal, the appellate court affirmed the decision of the court a quo, but with the exclusion of the award of attorneys fees and litigation expenses. The Supreme Court affirmed the challenged judgment of Court of Appeals, subject to the modification regarding the computation of the 6% legal rate of interest on the monetary awards granted therein to Pantejo. ISSUE: Whether petitioner airlines acted in bad faith when it failed and refused to provide hotel accommodations for respondent Pantejo or to reimburse him for hotel expenses incurred by reason of the cancellation of its connecting flight to Surigao City due to force majeur. HELD:

A contract to transport passengers is quite different in kind and degree from any other contractual relation, and this is because of the relation which an air carrier sustains with the public. Its business is mainly with the travelling public. It invites people to avail of the comforts and advantages it offers. The contract of air carriage, therefore, generates a relation attended with a public duty. Neglect or malfeasance of the carriers employees naturally could give ground for an action for damages. The discriminatory act of PAL against Pantejo ineludibly makes the former liable for moral damages under Article 21 in relation to Article 2219 (10) of the Civil Code. As held in Alitalia Airways vs. CA, et al., such inattention to and lack of care by the airline for the interest of its passengers who are entitled to its utmost consideration, particularly as to their convenience, amount to bad faith which entitles the passenger to the award of moral damages. Moral damages are emphatically not intended to enrich a plaintiff at the expense of the defendant. They are awarded only to allow the former to obtain means, diversion, or amusements that will serve to alleviate the moral suffering he has undergone due to the defendants culpable action and must, perforce, be proportional to the suffering inflicted. However, substantial damages do not translate into excessive damages. Herein, except for attorneys fees and costs of suit, it will be noted that the Courts of Appeals affirmed point by point the factual findings of the lower court upon which the award of damages had been based. The interest of 6% imposed by the court should be computed from the date of rendition of judgment and not from the filing of the complaint. The rule has been laid down in Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. vs. Court of Appeals, et. al. that when an obligation, not constituting a loan or forbearance of money, is breached, an interest on the amount of damages awarded may be imposed at the discretion of the court at the rate of 6% per annum. No interest, however, shall be adjudged on unliquidated claims or damages except when or until the demand can be established with reasonable certainty. Accordingly, where the demand is established with reasonable certainty, the interest shall begin to run from the time the claim is made judicially or extrajudicially (Art. 1169, Civil Code) but when such certainty cannot be so reasonably established at the time the demand is made, the interest shall begin to run only from the date the judgment of the court is made (at which time the quantification of damages may be deemed to have been reasonably ascertained). The actual base for the computation of legal interest shall, in any case, be on the amount finally adjudged. This is because at the time of the filling of the complaint, the amount of the damages to which Pantejo may be entitled remains unliquidated and not known, until it is definitely ascertained, assessed and determined by the court, and only after the presentation of proof thereon.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Symaco Trading Vs SantosDocument2 paginiSymaco Trading Vs Santosjay ugayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Atrium Management Corp. V. CA (2001) : G.R. No. 109491Document2 paginiAtrium Management Corp. V. CA (2001) : G.R. No. 109491Thoughts and More ThoughtsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prisma Construction & Development Corp vs. Menchavez GR No. 160545 March 9, 2010Document6 paginiPrisma Construction & Development Corp vs. Menchavez GR No. 160545 March 9, 2010morningmindsetÎncă nu există evaluări

- 34-Tuazon v. Heirs of Bartolome Ramos G.R. No. 156262 July 14, 2005Document4 pagini34-Tuazon v. Heirs of Bartolome Ramos G.R. No. 156262 July 14, 2005Jopan SJÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 90 Digested TD CasesDocument84 pagini11 90 Digested TD CasesShynnMiñozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PALE - Criticisms Against The Courts and JudgesDocument6 paginiPALE - Criticisms Against The Courts and JudgesGabrielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cases - Negotiable Instruments (Week 4)Document163 paginiCases - Negotiable Instruments (Week 4)Gelyssa Endozo Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest - MANILA ELECTRIC COMPANY v. NORDEC PHILIPPINESDocument3 paginiCase Digest - MANILA ELECTRIC COMPANY v. NORDEC PHILIPPINESBeau BautistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Commissioner v. Duberstein, 363 U.S. 278 (1960)Document15 paginiCommissioner v. Duberstein, 363 U.S. 278 (1960)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oblicon Garayblas Finals Reviewer 2019 PDFDocument8 paginiOblicon Garayblas Finals Reviewer 2019 PDFRomeo LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- R.A 8367 PDFDocument6 paginiR.A 8367 PDFreshell100% (1)

- ECC reviews accidental shooting death of soldier on overnight passDocument18 paginiECC reviews accidental shooting death of soldier on overnight passKyra Sy-SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sarmiento v. Sps. Cabrido, 401 SCRA 122 (2003)Document4 paginiSarmiento v. Sps. Cabrido, 401 SCRA 122 (2003)Fides DamascoÎncă nu există evaluări

- EAST WEST BANKING CASE DIGESTDocument28 paginiEAST WEST BANKING CASE DIGESTLegaspiCabatchaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tuna Processing, Inc. V. Philippine Kingford G.R. No. 185582 February 29, 2012Document30 paginiTuna Processing, Inc. V. Philippine Kingford G.R. No. 185582 February 29, 2012Juni VegaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Law Pertaining To Private Personal and Commercial Relations (Civil and Commercial Law)Document98 paginiThe Law Pertaining To Private Personal and Commercial Relations (Civil and Commercial Law)NoliÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2004 Bar ExamDocument7 pagini2004 Bar Exameinel dcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pcib v. CaDocument3 paginiPcib v. CaNicole MenesÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs Susan CantonDocument2 paginiPeople Vs Susan CantonJessamine OrioqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Credit Trans B (Thurs.) - Mid Term ExamDocument2 paginiCredit Trans B (Thurs.) - Mid Term Examjuna100% (1)

- 10-Makati Leasing and Finance Corp. vs. Wearever Textile Mills, Inc.Document9 pagini10-Makati Leasing and Finance Corp. vs. Wearever Textile Mills, Inc.resjudicataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Victorias Milling Co., Inc. vs. Mun. of Victorias, Negros Occidental, 25 SCRA 192, September 27, 1968Document21 paginiVictorias Milling Co., Inc. vs. Mun. of Victorias, Negros Occidental, 25 SCRA 192, September 27, 1968Daniela SandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Casabuena vs. CA, 286 SCRA 594Document3 paginiCasabuena vs. CA, 286 SCRA 594Xuagramellebasi100% (1)

- Food Subsidy Masterlist Sen Risa Hontiveros As of March 30Document50 paginiFood Subsidy Masterlist Sen Risa Hontiveros As of March 30IzackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine promissory note cases analyzedDocument13 paginiPhilippine promissory note cases analyzedRufino Gerard MorenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Top The Bar! Civpro Midterm 2 2020Document8 paginiTop The Bar! Civpro Midterm 2 2020Erwin SabornidoÎncă nu există evaluări

- TortsDocument19 paginiTortsMaFatimaP.Lee100% (1)

- Express Trust Over Immovable PropertyDocument2 paginiExpress Trust Over Immovable PropertyAustine Clarese VelascoÎncă nu există evaluări

- RemRev SyllabusDocument7 paginiRemRev Syllabusj531823Încă nu există evaluări

- Singson v. Bank of The Philippine Islands G.R. No. L-24837, June 27, 1968Document1 paginăSingson v. Bank of The Philippine Islands G.R. No. L-24837, June 27, 1968Hearlie OrtegaÎncă nu există evaluări

- TORTS AND DAMAGES CASE SUMMARYDocument62 paginiTORTS AND DAMAGES CASE SUMMARYCL DelabahanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civ Pro CasesDocument5 paginiCiv Pro CasesClaudine SumalinogÎncă nu există evaluări

- DigestDocument12 paginiDigestRiver Mia RomeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agent Liability in Contracts Signed Within AuthorityDocument60 paginiAgent Liability in Contracts Signed Within AuthorityRoxanne PeñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acar Vs RosalDocument2 paginiAcar Vs RosalJean HerreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- RULE 111 Crim ProcDocument10 paginiRULE 111 Crim ProcJovin Paul LiwanagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alcantara Vs AbbasDocument1 paginăAlcantara Vs AbbasGillian Caye Geniza BrionesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 - Villaroel V Estrada (1940)Document1 pagină5 - Villaroel V Estrada (1940)AttyGalva22Încă nu există evaluări

- Commodatum 1. Herrera vs. Petrophil Corporation, 146 SCRA 385 (1986)Document50 paginiCommodatum 1. Herrera vs. Petrophil Corporation, 146 SCRA 385 (1986)Jeorge Ryan MangubatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Torts Cases IDocument13 paginiTorts Cases IRgenieDictadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taxation Law 1 CasesDocument4 paginiTaxation Law 1 CasesAna RobinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edgar Jarantilla V. Court of Appeals and Jose Kuan Sing (Pau) FactsDocument31 paginiEdgar Jarantilla V. Court of Appeals and Jose Kuan Sing (Pau) FactsLhine KiwalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kwin Transcripts - InsuranceDocument84 paginiKwin Transcripts - InsuranceMario P. Trinidad Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Prisma V MenchavezDocument3 paginiPrisma V MenchavezKate Bernadette MadayagÎncă nu există evaluări

- THE INSULAR LIFE ASSURANCE COMPANY, LTD. vs. CARPONIA T. EBRADO and PASCUALA VDA. DE EBRADODocument2 paginiTHE INSULAR LIFE ASSURANCE COMPANY, LTD. vs. CARPONIA T. EBRADO and PASCUALA VDA. DE EBRADOReynaldo DizonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manuel Lim v. Court of AppealsDocument1 paginăManuel Lim v. Court of AppealsDayday AbleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Atiko Trans V Prudential Guarantee Case DigestDocument2 paginiAtiko Trans V Prudential Guarantee Case DigestLouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civpro - AnswerDocument5 paginiCivpro - AnswerVictor FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic v. SerenoDocument154 paginiRepublic v. SerenoJay-ar Rivera BadulisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trademarks Law - Lecture Outline: Reference: R.A 8293, Intellectual Property CodeDocument7 paginiTrademarks Law - Lecture Outline: Reference: R.A 8293, Intellectual Property CodeKobe BullmastiffÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robert Dino vs. Maria Luisa Judal-Loot, Et. Al.Document1 paginăRobert Dino vs. Maria Luisa Judal-Loot, Et. Al.LDC100% (1)

- Pil Jamon TipsDocument8 paginiPil Jamon TipsReyan RohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Banking Case Digest Pt. 2Document7 paginiBanking Case Digest Pt. 2Tien BernabeÎncă nu există evaluări

- CIR Vs MenguitoDocument1 paginăCIR Vs MenguitokoeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kitem Duque Kadatuan Jr. 1Document70 paginiKitem Duque Kadatuan Jr. 1jimart10Încă nu există evaluări

- Court Rules on Branch Profit Remittance Tax BaseDocument4 paginiCourt Rules on Branch Profit Remittance Tax BaseHazel FernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balatoc Mining vs Benguet ConsolidatedDocument2 paginiBalatoc Mining vs Benguet ConsolidatedSharon G. BalingitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dominican Province of The Philippines UST Central SeminaryDocument13 paginiDominican Province of The Philippines UST Central SeminaryNathaniel RemendadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catholic Vicar Apostolic V CA 165 Scra 515Document4 paginiCatholic Vicar Apostolic V CA 165 Scra 515Aleks OpsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court Rules on Interest Rates for LoansDocument16 paginiSupreme Court Rules on Interest Rates for LoansDan MilladoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise in Outlining The Codal Provisions On PartnershipDocument7 paginiExercise in Outlining The Codal Provisions On PartnershipMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparative Table - Trust, Agency, PartnershipDocument32 paginiComparative Table - Trust, Agency, PartnershipMousy Gamallo100% (1)

- Doj NPS ManualDocument40 paginiDoj NPS Manualed flores92% (13)

- RA 6657-Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law PDFDocument29 paginiRA 6657-Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law PDFMousy Gamallo100% (2)

- Agricultural Land Reform Code SummaryDocument58 paginiAgricultural Land Reform Code SummaryStephen CabalteraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chattel Mortgage: AnnumDocument2 paginiChattel Mortgage: AnnumRacky CaragÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic legal forms captionsDocument44 paginiBasic legal forms captionsDan ChowÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA 6657, As Amended by RA 9700Document23 paginiRA 6657, As Amended by RA 9700Mousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic legal forms captionsDocument44 paginiBasic legal forms captionsDan ChowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Demand Letter Sample PhillippinesDocument1 paginăDemand Letter Sample PhillippinesMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amending PD 1752 to Expand HDMF CoverageDocument3 paginiAmending PD 1752 to Expand HDMF CoverageMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- R.A. 7699 (Limited Portability Law) - 2Document2 paginiR.A. 7699 (Limited Portability Law) - 2Arkhaye SalvatoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- PD 27: Philippines Agrarian Reform Law SummaryDocument13 paginiPD 27: Philippines Agrarian Reform Law SummaryMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phases of a Contract of SaleDocument32 paginiPhases of a Contract of SaleMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- PD 1752-Amending The Act Creating The HDMF PDFDocument6 paginiPD 1752-Amending The Act Creating The HDMF PDFMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA 9700-CARP Extensions and ReformsDocument22 paginiRA 9700-CARP Extensions and ReformsMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presidential Decree No. 27Document1 paginăPresidential Decree No. 27rodolfoverdidajrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taxation Law Case DigestsDocument36 paginiTaxation Law Case DigestsMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Property Cases SummaryDocument2 paginiProperty Cases SummaryMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Credit Transactions - Lopez vs. CA, 144 Scra 671 (1982)Document7 paginiCredit Transactions - Lopez vs. CA, 144 Scra 671 (1982)Mousy Gamallo100% (1)

- Public Land Act Full TextDocument28 paginiPublic Land Act Full TextMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Credit Transactions - China Bank vs. CA, 270 SCRA 503 (1997)Document12 paginiCredit Transactions - China Bank vs. CA, 270 SCRA 503 (1997)Mousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fisheries CodeDocument38 paginiFisheries CodeMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lopez Vs Orosa, GR L-10817-18, 28 Feb 1958 Full TextDocument5 paginiLopez Vs Orosa, GR L-10817-18, 28 Feb 1958 Full TextMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oposa Vs Factoran Full TextDocument14 paginiOposa Vs Factoran Full TextMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fernando Vs CADocument6 paginiFernando Vs CAMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phases of a Contract of SaleDocument32 paginiPhases of a Contract of SaleMousy GamalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14 RGM V United PacificDocument4 pagini14 RGM V United PacificBelle MaturanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contracts Outline: Key Elements of Contract Formation and EnforcementDocument24 paginiContracts Outline: Key Elements of Contract Formation and EnforcementffbugbuggerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doctrine of Unconscionability Its DevelopmeDocument17 paginiDoctrine of Unconscionability Its DevelopmeLenny JMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hire Purchase AgreementDocument4 paginiHire Purchase AgreementSudeep SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumer ActDocument13 paginiConsumer ActAvianne Villanueva100% (1)

- Superior Court of Virginia County of AblemarleDocument10 paginiSuperior Court of Virginia County of AblemarleRobert WatkinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bush Contracts Cheat SheetDocument11 paginiBush Contracts Cheat SheetSarah AlfaddaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PNB V Philippine Vegetable DigestDocument9 paginiPNB V Philippine Vegetable Digestmickeysdortega_411200% (1)

- Indian Contract Act - Question AnswerDocument0 paginiIndian Contract Act - Question Answerganguly_ajayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contract Law and Enforceability AnalysisDocument13 paginiContract Law and Enforceability AnalysisVictorian_Roses100% (1)

- Contract Law - Key Principles of Incapacity (38Document17 paginiContract Law - Key Principles of Incapacity (38Christchurch BranchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Totrs CompleteDocument374 paginiTotrs CompleteThea Thei YaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Melvin Aron Eisenberg - Foundational Principles of Contract Law-Oxford University Press, USA (2018) PDFDocument903 paginiMelvin Aron Eisenberg - Foundational Principles of Contract Law-Oxford University Press, USA (2018) PDFAndreea Ceaușu83% (6)

- Contract Law OutlineDocument17 paginiContract Law OutlineErin Kitchens Wong100% (1)

- Undue InfluenceDocument18 paginiUndue InfluenceNaina ReddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contracts II Final OutlineDocument24 paginiContracts II Final Outlinepmariano_5Încă nu există evaluări

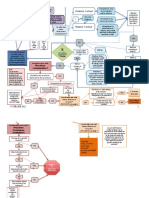

- Contracts FLOW Chart PDFDocument6 paginiContracts FLOW Chart PDFSara ZamaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sssssss WDocument27 paginiSssssss WSandeep RajpootÎncă nu există evaluări

- Product Liability ReportDocument3 paginiProduct Liability Reportmacmac123450% (1)

- Oliver SmithDocument5 paginiOliver SmithharkaosiewmaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Common Law Approach and Case BriefingDocument111 paginiCommon Law Approach and Case BriefingMarechal CÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 7Document12 paginiChapter 7Shafeela ThasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unconscionable Contracts Ordinance Cap.458 Sections ExplainedDocument2 paginiUnconscionable Contracts Ordinance Cap.458 Sections ExplainedSinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article Review: Equity Opportunism in The Law of Contract: A Case Study in Fusion by Diffusion - Tan Zhong XingDocument9 paginiArticle Review: Equity Opportunism in The Law of Contract: A Case Study in Fusion by Diffusion - Tan Zhong XingVedika SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ora Lee Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture Co. United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit, 1965. 121 U.S.App.D.C. 315Document3 paginiOra Lee Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture Co. United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit, 1965. 121 U.S.App.D.C. 315kalinovskayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Law Quiz QuestionsDocument9 paginiBusiness Law Quiz QuestionsWilliamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leeber v. Deltona Corp.Document2 paginiLeeber v. Deltona Corp.crlstinaaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Filinvest vs CA Decision on Payment DisputeDocument16 paginiFilinvest vs CA Decision on Payment DisputeCarmela Lucas DietaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contracts OutlineDocument25 paginiContracts OutlineZach LanierÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCMP Construction Corp., Petitioner, vs. Monark Equipment CorpDocument5 paginiMCMP Construction Corp., Petitioner, vs. Monark Equipment CorpCessy Ciar KimÎncă nu există evaluări