Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Blackwell Publishing and Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, Inc. Are Collaborating With JSTOR

Încărcat de

Rashela DycaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Blackwell Publishing and Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, Inc. Are Collaborating With JSTOR

Încărcat de

Rashela DycaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Matrix of Memory Author(s): Peter Schneider Source: JAE, Vol. 34, No.

1, How Not to Teach Architectural History (Autumn, 1980), pp. 2324 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1424725 Accessed: 30/04/2010 09:53

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Blackwell Publishing and Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to JAE.

http://www.jstor.org

Peter Schneider teachesin the Department at Louisiana Tech University. ofArchitecture

Matrix

of

Memory

conventionally tend to regard the work of fiction as being the polar opposite of works of nonfiction. We see the one as a story, a fabricationof fantasy, the other as a record of fact. Both however inevitably result out of the fictive act; the act of creating fragile structures in the mind which serve to make sense of things, which cause our interpretations and understandings of reality to present themselves. Both are inevitably what Paul Valery, the French poet and aesthetic philosopher, terms, "works of the mind," and as such they belong to that class of works which the mind makes for its own use. Both are works, rather than productions. In composing fictions and non-fictions alike our conscious action is that of "making" rather than that of "matching,"and in common with all other works of the mind they "do not reproduce the visible, rather they make visible."'1 Friedrich Nietzsche has said that "What can be thought must certainly be a fiction." We think fictively, give shape to content, and the act of fiction may in these terms be seen as analogous to the act of thought itself. The fictive nature and quality of our thinking gives form to meaning and expression to idea, and the different classes of fictive work may be seen as a general system through which our thinking becomes expressed. Our thinking and the fictive nature of our thoughts results from our conscious combination and recombination of memories. "We never come to thoughts, they come to us, and that is why thinking holds to the coming of what has been and is remembrance.9"2 If thinking can be seen to by synonymous with remembrance, how then do we think? Alfred North Whitehead, speaking about the movement of a thought from the state of the unknown to the state of the known-from "Silence to Light" in Louis Kahn's terms-sees the thought as moving through three distinct stages or modes: the the stage of isolation and stage of discovery, the stage of concentration. The general action which seems to lie at the base of our mode of thinking is that of the framing of distinctions of two kinds. We distinguish between this and that in the first place, and then frame distinctions between this and this. Our use of these two very specific distinction types relates directly to our modes of thinking in the discovery-isolation-concentration sequence, and con-

We

sequently to the two general classes of memory we must manipulate. The nature and quality of these distinct memory types will, if we realize them, allow us to understand the nature of these two distinctive acts we use in thinking a thought, in shaping content. When we frame distinctions of the this-that type, we work with memories, ideas and facts which are non-synonymous, which differ in both their form and their meaning, their shape and their content. These memories have the characteristicof singularity, of particularity, of difference. In composing a thought we exploit this characteristicof difference; we resolve the ambiguities latent in the signs of our inner language, discover new similarities, seemingly invisible connections. The Theory of Relativity, its fiction, was generated when an ambiguity between the concepts "gravity"and "light" was perceived and resolved. Differences came to be seen as similarities, and a new and powerful fiction emerged. Synonymous memories, on the other hand, possess characteristics of similarity. Their particular forms may differ, but the meaning they express remains constant; they exist as different shapes of the same content. Existing as distinctions between "this" and "this," they belong to the realm of the analogous and the metaphorical. In giving shape to content, in expressing our thoughts, we exploit the similarities existing between synonymous expressions rather than their differences. We use the device of the analog and the metaphor, rather than that of the latent ambiguity. The Theory of Relativity was first expressed in the inner language of the mathematician. In order to make it generally understood, it was re-stated in terms of accelerating elevators, moving trains and stationary observers, moving tramcarsand moving pedestrians-that is, using familiar analogous relationships. The two distinct classes of memory, therefore, can be seen to have specific characteristicsof use in our process of framing a thought; and the degrees of relationship between the intellectual shapes of the incept, the concept and the percept and the "this-that" and "this-this"distinctions are clearly evident. The word "history" comes to us almost directly and with very little modification from the Latin word "historia." Its Latin

meaning is narrative, story or account. While the Latin shape "historia" is very close to that of our present shape "history," the content it carries has been modified. In modern terms we tend to see history as fact rather than as the fiction which its original content implies. If we dig deeper into "history's" past, into the evolving morphology of its particular shape, we find that the Latinword has been generated by a complex of interconnections between the related memories and fragments of its Greek roots. The common content of these related fragments is the Greek form "idea," which represents the notions of form, look, semblance, shape, and which is the common root of our present words "idea"and "vision"and their derivatives. Before its meaning had been modified and given new direction by Plato's philosophical device of the idea as a representation of ideal form, the word "idea" carried and held the meaning of form: shape in the sense of that which is seen, that which is capable of perception. History became the act of seeing and giving shape to things: facts, events and experiences in the context of reality and of time; of seeing the discernable shape of content. In this original sense we are able to see history and fiction as being analogous, as sharing common origin in the action of shaping and forming. History may, as such, beseenas a visionaryact, and the connections existing betweenits visionaryactionsand the actions offiction become clearlyimplied. History begins to exist as a specialized fiction of reality, and the negative connotations of the Latin word "historia"-of its quality as story, narrative, myth, legend-are consequently avoided. The content we currently assign to history, that is, its existence in the realm of the factual rather than in the realm of the actual, would seem to have been generated as a pervasive reaction to the negative connotations in "historia."Its origiconttined nal content, its powerful and essential fictive quality, has been bleached out with the passage of time, seemingly in the interests of increasing its theoretical nature, its epistemological stature, and its place and position in Plato's famous "divided line." Its essential quality, however, is that of a fiction, a fictive composition, and the writing and teaching of history must be 23

Beginning students have difficulty accepting the fact that history is indeterminate, and that accounts for a lot of the doctoring up by architectural historians at the undergraduate level. It is extremely distressing for students to find that what they are learning is probably inaccurate--Dora Wiebenson.

The problem comes about when people attempt to describe the causes of historical monuments in terms of their feelings at the moment, without actually knowing anything about how and why they were made, and the context. On the other hand, the problem with architectural historians comes about when they stupidly follow a method because they are in this business to grind out material according to the method, never thinking about questions of quality or whether a thing is worth studying in the first place or why we should study it, and whether anybody will profit--Richard Betts.

One can think of buildings as existing in a temporal continuum and as existing in a spatial continuum. In a sense that gives you two axes. The building exists at the intersection of two axes. You have a spatial system which requires that you experience it, as directly as possible, or with surrogates as perfect as you can manage to assemble. But you can also experience it on a time continuum. I think the dominance of one over the other is very dangerous. The time continuum is what Barzun calls the "before and after school of history," in which something is simply identified as something which exists between this and that event; from that point of view that model is adequate. But I would also argue that the experiential model is also inadequate by itself. One should look at a building in both ways, simultaneously, not in one way or the other--Claus Seligmann.

seen in the contextof the fictiveandvi- particularclass stems from the latent qual- its type, the precedent and its patterns, the

sionary act, the act of thought itself. We teach history, and, in its teaching, teach fictions of memory. We give shape to the discernable fictions of the past and, by so doing, make available the rich tapestry of ideas, facts, things, events, forms, acts, personalities, and fictions which constitute what might be considered as necessary memories. We teach histories rather than History, and section the broad perspectives of time into specialized fictions such as the history of art, the history of language, the history of philosophy, the history of architecture and the history of social institutions in order to limit the vast landscape of available fragments of the past; in order to make available the particular classes of necessary memory which will allow new and original expressions, fictions of a special class, to be generated. In teaching history we explore the past, the memory, of the expressions generated within a particular system of expression, and through this exploration we then create a potential in those we teach for the shaping of new fictions, new expressions, within that particularsystem. The only requirement that the nature of the fictive act imposes on how we teach memories of a 24 ities inherent in memories themselves. We think, compose our thoughts, by manipulating memories which are nonsynonymous. We express our thoughts, our fictions, by manipulating memories which are synonymous. In thinking, in deriving content, we choose initially between different ways of saying different things; we then express our thought, shape our content, by choosing between different ways of saying the same thing. If we are to create the potential, the framework, within which the fictive act can take place, the memories we teach must clearly fall into each of these two dominant classes. We cannot teach one class, and not the other. The two are mutually inclusive, and just as we do not think a thought and then express it but think it by expressing it, we cannot manipulate the non-synonymous without the simultaneously manipulating synonymous. Therefore, the teaching of history, if we are to do it effectively, imposes its own requirement: We must teach both different ways of expressing different things within a particularhistoric or fictive system, and the different ways of expressing the same thing generated within that system. We must teach both the class and idea and its images, the meaning and its expressions-the content and its different shapes. We therefore teach history as a matrix of memory, and through this make remembrance, and consequently thought, possible. We generate the expectations of things to come, the necessary "recessions of the mind from which come that which is not yet said, not yet made"-the expectation of future fictions, the unseen and invisible shapes of the yet-to-be discovered content.

References 'Paul Klee, "Creative Credo," in Theories of Modern Art, HerschelB Chipp editor (Berkeley: Univ of California, 1968), p 182. 2Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language and Thought (New York:Harperand Row, 1971). Poylani, Michael, Meaning Chicago: University of Chicago, 1975. Ryle, Gilbert, The Concept of Mind. London: Hutchinson, 1949.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Some Elements of StructuralismDocument8 paginiSome Elements of StructuralismDhimitri BibolliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Post StructuralismDocument26 paginiPost StructuralismnatitvzandtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elements of StructuralismDocument6 paginiElements of StructuralismtoltecayotlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hans Jonas Homo PictorDocument21 paginiHans Jonas Homo PictorDiana Alvarado MeridaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LIMA & MELLO - Social Representation and MimesisDocument21 paginiLIMA & MELLO - Social Representation and MimesisHugo R. MerloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wisdom and Not: Defining Mesopotamian WisdomDocument14 paginiWisdom and Not: Defining Mesopotamian WisdomMichael S.Încă nu există evaluări

- The Uncertainty of Discursive CriticismDocument38 paginiThe Uncertainty of Discursive CriticismBaha ZaferÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Kilometro en La Ciudad!: Framework!Document8 pagini1 Kilometro en La Ciudad!: Framework!Camila Come CarameloÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and ReasonDe la EverandThe Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and ReasonEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (3)

- Imagination as an expansion of experienceDocument20 paginiImagination as an expansion of experienceCamilo Andrés Salas Sandoval100% (1)

- Paul Ricoeur's Oneself As AnotherDocument10 paginiPaul Ricoeur's Oneself As AnotherAna DincăÎncă nu există evaluări

- Freeman Poetic - IconicityDocument16 paginiFreeman Poetic - IconicityCarmenFloriPopescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- HOLLAND TransactiveCriticismReCreation 1976Document20 paginiHOLLAND TransactiveCriticismReCreation 1976Augustas SireikisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Muse 65109-2290257Document17 paginiProject Muse 65109-2290257allistergallÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ricoeur, Paul - 1965 - Fallible Man 11 PDFDocument1 paginăRicoeur, Paul - 1965 - Fallible Man 11 PDFMennatallah M.Salah El DinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social ConstructionDocument2 paginiSocial ConstructionAmal H AlqariniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joan AnalysisDocument3 paginiJoan AnalysisDuran Joan Del RosarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artificial Intelligence in Sci-Fi Explores the Posthuman ConditionDocument14 paginiArtificial Intelligence in Sci-Fi Explores the Posthuman Condition////Încă nu există evaluări

- Zwicky, Jan - Wisdom & Metaphor PDFDocument272 paginiZwicky, Jan - Wisdom & Metaphor PDFCamila Come CarameloÎncă nu există evaluări

- SYMBOLS, MYTHS, AND RITUALS IN HUMAN SOCIETYDocument39 paginiSYMBOLS, MYTHS, AND RITUALS IN HUMAN SOCIETYJoaquin Solano100% (3)

- Final Paper On German PhilosophyDocument16 paginiFinal Paper On German PhilosophyAngela ZhouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Susanne K. Langer, Abstraction in Science and Abstraction in ArtDocument6 paginiSusanne K. Langer, Abstraction in Science and Abstraction in Artnana_kipianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Morgachev, Sergey. Contact // Morgachev, S. On The Boundaries of Analytical Psychology. Moscow, Class. 2016Document10 paginiMorgachev, Sergey. Contact // Morgachev, S. On The Boundaries of Analytical Psychology. Moscow, Class. 2016Sergey MorgachevÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fiction, Between Inner Life and Collective MemoryDocument12 paginiFiction, Between Inner Life and Collective MemoryCarlos AmpueroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophy of Art After Analysis and RomanticismDocument18 paginiPhilosophy of Art After Analysis and RomanticismNayeli Gutiérrez Hernández100% (1)

- The Spoils of Poynton and The Properties of Touch by Thomas J PoyntonDocument29 paginiThe Spoils of Poynton and The Properties of Touch by Thomas J PoyntonkbchowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Margolin, Uri (1995) - 'Possible Worlds in Literary Theory'Document5 paginiMargolin, Uri (1995) - 'Possible Worlds in Literary Theory'Anonymous b9qvIToDpFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collective MemoryDocument11 paginiCollective MemoryLamiaa HassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eliot, Tradition & The Individual Talent 1Document16 paginiEliot, Tradition & The Individual Talent 1Richard FoxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compressao Construcao SubjetividadesDocument6 paginiCompressao Construcao SubjetividadesAdriana SilvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art As Guerilla MetaphysicsDocument10 paginiArt As Guerilla MetaphysicsJamie AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evald Ilyenkov 1960Document183 paginiEvald Ilyenkov 1960gdupres66Încă nu există evaluări

- The Enemy in The ConceptDocument13 paginiThe Enemy in The ConceptsambjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Christos Yannaras - Trans of Philosophie Sans RuptureDocument17 paginiChristos Yannaras - Trans of Philosophie Sans RuptureJames L. KelleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Descola-Modes of Being and Forms of PredicationDocument10 paginiDescola-Modes of Being and Forms of PredicationJesúsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jeffrey R. SmittenDocument12 paginiJeffrey R. SmittenRenata PerimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structural Analysis of NarrativeDocument8 paginiStructural Analysis of NarrativeAnonimous AdhikaryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gauthier Analyzes Social Contract Theory as IdeologyDocument36 paginiGauthier Analyzes Social Contract Theory as IdeologyMartínPerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zwicky, Jan - Wisdom & MetaphorDocument272 paginiZwicky, Jan - Wisdom & MetaphorJanina Vienišė100% (1)

- A Return To Humanism in Architecture: English Abstracts 8 4Document13 paginiA Return To Humanism in Architecture: English Abstracts 8 4Sali KipianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ilyenkov - On The Relation of The Notion To The ConceptDocument19 paginiIlyenkov - On The Relation of The Notion To The ConceptbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Institutional Bodies Spatial Agency and The DeadDocument18 paginiInstitutional Bodies Spatial Agency and The Deadorj78Încă nu există evaluări

- Von Glaserfeld - Facts and Self From A Constructivistic Point of ViewDocument12 paginiVon Glaserfeld - Facts and Self From A Constructivistic Point of Viewapi-3719401Încă nu există evaluări

- Meetings of Minds Dialogue, Sympathy, and Identification, in Reading FictionDocument16 paginiMeetings of Minds Dialogue, Sympathy, and Identification, in Reading FictionlidiaglassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rhetoric Narration PDFDocument16 paginiRhetoric Narration PDFJessicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cover Letter and Essay For Postdoc Research at Warwick Philosophy - Cengiz ErdemDocument24 paginiCover Letter and Essay For Postdoc Research at Warwick Philosophy - Cengiz ErdemCengiz ErdemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Catharsis and Psychodrama (Moreno)Document37 paginiMental Catharsis and Psychodrama (Moreno)Iva Žurić100% (2)

- Theory and Practice - Group Identity and The Alevi KurdsDocument21 paginiTheory and Practice - Group Identity and The Alevi KurdsMatthiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay 1Document13 paginiEssay 1robertrosencransÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lacanian Orders Symbolic Real ImaginaryDocument4 paginiLacanian Orders Symbolic Real ImaginarybikashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strathern, M. Reading Relation BackwardsDocument17 paginiStrathern, M. Reading Relation BackwardsFernanda HeberleÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Limits of Limits: Derridean Deconstruction and The Archival InstitutionDocument16 paginiThe Limits of Limits: Derridean Deconstruction and The Archival InstitutionfistfullofmetalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fredric Jameson - Ideology of The Text - The Ideologies of Theory IDocument28 paginiFredric Jameson - Ideology of The Text - The Ideologies of Theory IAmitabh Roy100% (1)

- Atnip TAD46 1 pg40 54 PDFDocument15 paginiAtnip TAD46 1 pg40 54 PDFLindsayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sociological Critique of Reification and ConsciousnessDocument17 paginiSociological Critique of Reification and Consciousnessvikas_psy100% (1)

- When Truth Is at Stake: Examining Contemporary LegendsDocument22 paginiWhen Truth Is at Stake: Examining Contemporary LegendsCarlos Renato LopesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Studio Themes PDFDocument3 paginiStudio Themes PDFTiago RosadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full TextDocument13 paginiFull TextMarsha FieldsÎncă nu există evaluări

- REG19 Industrial Capacity London Plan SPG 2007Document84 paginiREG19 Industrial Capacity London Plan SPG 2007Rashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Tree Is A Tree Is A Building - Lebbeus WoodsDocument9 paginiA Tree Is A Tree Is A Building - Lebbeus WoodsRashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

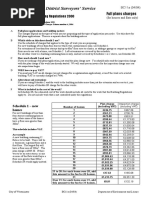

- Building Regs - Full Plans ChargeDocument2 paginiBuilding Regs - Full Plans ChargeRashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Towards Experiential Representation in Architecture: Journal of Architecture and Urbanism January 2016Document14 paginiTowards Experiential Representation in Architecture: Journal of Architecture and Urbanism January 2016Rashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A - Structure Building RegsDocument46 paginiA - Structure Building RegsRashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 000 Best Practices Course OutlineDocument1 pagină000 Best Practices Course OutlineRashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- B V1 - Fire On DwellingsDocument87 paginiB V1 - Fire On DwellingsRashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Formulating Human Settlements - Informalization of Formal Housing (KTT Vietnam)Document4 paginiFormulating Human Settlements - Informalization of Formal Housing (KTT Vietnam)Rashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Space PlaceDocument34 paginiSpace PlaceZhennya SlootskinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architecture and EmotionDocument48 paginiArchitecture and Emotionghadeerco100% (3)

- Edgar Francis - 2005 - THESIS - Islamic Symbols and Sufi Rituals For Protection and HealingDocument277 paginiEdgar Francis - 2005 - THESIS - Islamic Symbols and Sufi Rituals For Protection and Healinggalaxy5111Încă nu există evaluări

- HabitatDocument20 paginiHabitatRashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architectural History Benjamin and HolderlinDocument26 paginiArchitectural History Benjamin and HolderlinRashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3171430Document13 pagini3171430Rashela DycaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modernizing The Academic Teaching and Research Environment: Jorge Marx Gómez Sulaiman Mouselli EditorsDocument216 paginiModernizing The Academic Teaching and Research Environment: Jorge Marx Gómez Sulaiman Mouselli EditorswozenniubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science Technology and Society Week 2Document6 paginiScience Technology and Society Week 2riza mae FortunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Man As A Thinking BeingDocument37 paginiMan As A Thinking BeingSharmin ReulaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Castiglione Warren - Eight Theoretical Issues 2006Document11 paginiCastiglione Warren - Eight Theoretical Issues 2006Jefferson ZarpelaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sarah Pink - Woman Camera and Bullfighting - Visual Culture As Anthropological KnowledgeDocument17 paginiSarah Pink - Woman Camera and Bullfighting - Visual Culture As Anthropological KnowledgeEd PereiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- (By Geaney, Jane) Language As Bodily Practice in e 3559799 PDFDocument352 pagini(By Geaney, Jane) Language As Bodily Practice in e 3559799 PDFMahmud Erol KilicÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRS DollowayDocument46 paginiMRS DollowayjavaidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Performative Architecture: Mergence and Emergence in DesignDocument233 paginiPerformative Architecture: Mergence and Emergence in Designpradipta roy choudhuryÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cone of ExperienceDocument8 paginiThe Cone of ExperienceK wongÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1991 Book ClinicalPsychologyDocument536 pagini1991 Book ClinicalPsychologyDenís Andreea Popa100% (2)

- Carrington'S Kitchen Carrington'S Kitchen: W&M Scholarworks W&M ScholarworksDocument19 paginiCarrington'S Kitchen Carrington'S Kitchen: W&M Scholarworks W&M ScholarworksAmerica SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carl JaspersDocument4 paginiCarl JaspersAnalouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Freedom Through Creative Thinking - Part1Document33 paginiFreedom Through Creative Thinking - Part1hanako1192100% (1)

- Activity Sheets Module 1 - Personal DevelopmentDocument12 paginiActivity Sheets Module 1 - Personal Developmentthea medrano60% (5)

- 8 The Material and Economical SelfDocument6 pagini8 The Material and Economical SelfCRUZ, ANNA MARIELLEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wordsworth's The Prelude Poetic TheoryDocument9 paginiWordsworth's The Prelude Poetic TheoryJia NoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foundations of Problem-Based Learning: The Society For Research Into Higher EducationDocument214 paginiFoundations of Problem-Based Learning: The Society For Research Into Higher EducationsuhailÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3A668BC6040Document6 pagini3A668BC6040Anonymous I3VKoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kartika NurhandayaDocument106 paginiKartika NurhandayasadhanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arnold R. Shore, John M. (Michael) Carfora - The Art of Funding and Implementing Ideas - A Guide To Proposal Development and Project Management-SAGE Publications, Inc (2010) PDFDocument113 paginiArnold R. Shore, John M. (Michael) Carfora - The Art of Funding and Implementing Ideas - A Guide To Proposal Development and Project Management-SAGE Publications, Inc (2010) PDFRichard Oduor OdukuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Teaching PhilosophiesDocument87 paginiUnderstanding Teaching PhilosophiesMelo fi6100% (3)

- Space in ArchitectureDocument7 paginiSpace in Architectureicezigzag100% (1)

- Impact of Intellectuals and Philosophers in French Revolution 1789Document4 paginiImpact of Intellectuals and Philosophers in French Revolution 1789Dinesh HegdeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gaston Bachelard's Philosophy of ScienceDocument17 paginiGaston Bachelard's Philosophy of Sciencegregory mathiouwÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inside The Entrepreneurial Mind From Ideas To RealityDocument10 paginiInside The Entrepreneurial Mind From Ideas To Realitymikee albaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philo Module 1 W1 and 2Document15 paginiPhilo Module 1 W1 and 2gavint skynardÎncă nu există evaluări

- From The Science To The HumanitiesDocument10 paginiFrom The Science To The Humanitiesdwi ayu marlinawatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conceptual Foundation of Human Rights: Right to LifeDocument4 paginiConceptual Foundation of Human Rights: Right to LifeBejie AclaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- ABC1Document3 paginiABC1Bkibru aetsubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study Guide gr03 2020Document154 paginiStudy Guide gr03 2020api-292325707Încă nu există evaluări