Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

International Journal of Education & The Arts

Încărcat de

Andreia MiguelDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

International Journal of Education & The Arts

Încărcat de

Andreia MiguelDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

International Journal of Education & the Arts

Editors Margaret Macintyre Latta University of Nebraska-Lincoln, U.S.A. Christine Marm Thompson Pennsylvania State University, U.S.A.

http://www.ijea.org/

Volume 12 Number 7

ISSN 1529-8094

July 18, 2011

Circles of (Im)perfection A Story of Student Teachers Poetic (Re)Encounters with Self and Pedagogy

Sarah K. MacKenzie Bucknell University, U.S.A.

Citation: MacKenzie, S. K. (2010). Circles of (im)perfection: A story of student teachers poetic (re)encounters with self and pedagogy. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 12(7). Retrieved [date] from http://www.ijea.org/v12n7/.

Abstract Teaching is vulnerable work where self and other enter into intimate encounters that can change ones sense of self and purpose within the world. Through this poetic rendering, I seek to piece together a story of communal becoming within the space of a student teaching seminar. The work was collaborative and ongoing as students engaged with one anothers words and began to (re)write their relationships with themselves, the community, their peers, and practice. Boundaries were blurred, selves disrupted as student teachers began to engage with their own positions and perceptions of the world around them, (re)encountering pedagogy in a space of praxis.

IJEA Vol. 12 No. 7 - http://www.ijea.org/v12n7/

New Beginnings and Introductions They walk amidst laughter Tears becoming bright glistening anticipation Here we clap for them a line of black robes seeking as they enter into the space of the unknown We have been there awaiting our own arrival pieces As I write this, my student teachers are graduating eager and unsure as they step out of the life they have known for four years to embrace the life they have for so long imagined. I have high hopes for this dynamic group of eight women; however, I know the path they have chosen is uneven and unpredictable. Teaching is vulnerable work where self and other enter into intimate encounters that change ones sense of identity and purpose within the world. It is a profession that is both fulfilling and trying as one works to weave idealism with expectation, amidst a culture that often dismisses the unspoken challenges of a misunderstood profession. Few outside the classroom can ever be truly aware of the facets of self that are continuously on the move for young teachers. I think in fact, very few young teachers are aware of this movement and if they are, they do not recognize that it is something that is both shared and unique. Instead, many of the beginning teachers I have worked with, including myself, find themselves alone in their negotiations, perhaps at times feeling like failures as they begin to lose sight of the order and the images of self they had identified with when they stepped into their first education course. Across this space, I seek to piece together a story of communal becoming within the context of a student teaching seminar where students came to interrogate practice, while making sense of and accepting (their imperfect) selves as teachers. While starting perhaps first with the fragments of my own experiences as a student teacher, I seek to piece together a holistic story about uncomfortable beginnings, as I consider what happened when my students were invited to engage in artful and spiritually oriented self-inquiry as a means to explore themselves as teachers. From the first day of our student teaching seminar, student teachers were asked to engage in writing and art-making practices that placed them in the position of reflective inquirer as they tried to make sense of what they observed in the classrooms and communities

MacKenzie: Circles of (Im)perfection

where they would be/were teaching, while acknowledging their own desires and sense of experience. The work was collaborative and ongoing as students engaged with one anothers words and began to rewrite their relationships with themselves, the community, their peers, and practice. As student teachers began to engage with their own positions and perceptions of the world around them, they arrived at a new sense of self and community within practice, reencountering pedagogy in a space of praxis. Pondering Poetically To frame the lens of my storytelling, I draw on poetry as a means to return and research the experience. The poetry is fragmented, interrupted by more traditional research prose, shifting then to collective creations drawn directly from the experience. Poetic inquiry is not about answers, but as Leggo (2006) remarks, Instead a poetics of research is about searching, and returning to the texts of our searching, again and again, constantly ready for surprises (p. 90). I make no claims in my words but rather I seek to engage with them in process as a means to discover new patterns, relationships and ideas. Through poetic inquiry, knowing is always unfolding, blurring and becoming, sending off reverberations of language, sound, and emotion to be distorted, embraced, and reorganized toward new meaning. Brady (2009) remarks, Nothing speaks for itself. Interpretation is as necessary to human life as breathing (p. xi). The nature of poetry is such that through the senses, it creates spaces for one - the reader and writer, to enter into meaning. This process does not simply involve a collection of facts; rather, the aesthetic nature of poetry invites one to find multiple points of entry and directions for interpretation. The value of poetry within research and education is that it moves beyond the concrete answers of positivism, toward praxis and dialogue. Through poetry, the reader and writer negotiate meaning across language to discover truths about self and experience. The meaning that is negotiated may include facts, but it also includes the imaginative qualities of living within experience. It is these imaginative qualities that create alternate spaces for movement and ways of seeing the world. Luce-Kapler (2009) highlights, Poetry has a way of drawing us toward a phenomenon so that we feel the emotional reverberations of a shared moment (p. 75). Through poetry, knowing moves toward a space of plurality, where emotion and intellect, self and other unite traveling beyond the confines of isolation and Truth, toward communion and recognition of the wonders of simply being within any experience. Fragments of (Im)perfection Imperfection is at the root of teaching, of being humanyet many of us, especially preservice teachers, find ourselves seeking some image, presentation of perfection. One only has to reference various curriculum materials or teacher education textbooks to see that there is a

IJEA Vol. 12 No. 7 - http://www.ijea.org/v12n7/

level of expectation, a socially accepted perception of the act of teaching that separates the teacher from the curriculum, the teacher from the student and instead transform the teacher into a mythic, all-knowing perfectionist who knows and performs best practice (Sameshima, 2008). As Davis and Sumara (2007) note almost all our formal educational experiences have been oriented by the question How do you make people learn what you want them to learn? (p. 56). Student teachers have been familiarized with these normalized, effective practices of teaching from the time they first enter the classroom as a childand for some even earlier. It is these defined discourses of teaching that create a single faceted image of the experience of teaching or perhaps what might otherwise be thought of as the doing of teaching. However, as Ayers (1993) so eloquently reminds us: A life in teaching is a stitched-together affair, a crazy quilt of odd pieces and scrounged materials, equal parts invention and imposition. To make a life in teaching is largely to find your own way, to follow this or that thread, to work until your fingers ache, your mind feels as if it will unravel, and your eyes give out, and to make mistakes and then rework large pieces. It is sometimes tedious and demanding, confusing and uncertain, and yet it is as often creative and dazzling: Surprising splashes of color can suddenly appear at its center; unexpected patterns can emerge and lend the whole affair a sense of grace and purpose and possibility (p.1). This quilt is a part of what Palmer (1998) refers to as the inner landscape of the teaching self, (p.4) a batting of sorts that connects the pieces, keeping them insulated and warm. But this batting or landscape serves no purpose without the threads and fabric of history, experience, interaction, and emotion. When babies are born, they are immediately engaged in the process of making sense of their place in the world, their eyes begin to roam, fingers touchthey mimic and make sense of the moment by observation of self and others. This process is ongoing, however, as we grow, many of us fall into the trap of perceiving our worth through the acknowledgement and direction of others. This can be especially strong for teachers, who find themselves, working daily within a culture of evaluation. And it is this culture that often idealizes ritualistic performance of the rational, isolating many beginning teachers from the familial experience of love and acceptance (Grumet, 1988). However, like the quilt or mosaic, each of our unique facets does not exist in a vacuum, rather each piece of our being emerges through interaction. Being human is not rational rather it is relational. Far too often relationality is silenced as teachers are asked to engage in ritualized best practices; so intent on the perfect performance, a desire often arising from fear (Boler, 1999), that they lose sight of themselves as well as the others who are involved in that performance. And those others, that self do not simply exist

MacKenzie: Circles of (Im)perfection

emotionless within the vacuum of the classroom, rather they bring with them every past experience, pain, love and desire when they step foot in the classroom. While these stories are always fluid and shifting, they lay themselves upon the (inner) landscape, silently playing a role as experience begins to take shape upon the canvas of the classroom. Leggo (2008) notes, As a teacher, I do not leave my home and family experiences behind me when I drive to campus or when I enter the classroom. And I do not leave my past either. I am the person I am because of the experiences and people and places that comprise my life and my living (p. 91). Teachers are thinking, feeling beings, who carry with them layers of stories that shape the person they are within a given movement. Teaching itself is a story or series built upon other stories, never ending and always unpredictable. Burning embers of yesterday etch their yearning upon the landscapes interior shifting movement toward the (un)predicatable A Mirrored Circle The mandala can serve as a metaphor for the complex experience of teaching, in relationship to its patterns, order, and ambiguity; all of which work together to create a story or image often beautiful, but always with meaning. Trungpa (1991) describes the mandala as a space to create a situation that is based on a territory or boundary (p. 6). The nature of this space is ambiguous and alive, even in its fixed shape shifting in meaning across time and depending on those interacting with the mandala. Teachers enter into a space as individuals shaped by past experiences yet their identity is simultaneously shifting within the space as a result of actions, expectations, and desire (their own and those of others). Trungpa (1991) highlights the idea of orderly chaos noting It is orderly, because it comes in a pattern; it is chaos because it is confusing to work with that order (p. 1). This orderly chaos exists within the classroom, especially when it comes to the experience of student teachers. Pre-service teachers are provided with neat outlines of best practices and lesson plans, hopefully informed by theory, and one could easily fall under the assumption then that the practice is simple, orderly and predictable. These assumptions can be powerful fictions (Rossiter, 1997) shaped not only by the often orderly nature of ones traditional education as a teacher, but also by

IJEA Vol. 12 No. 7 - http://www.ijea.org/v12n7/

deeply embedded ideologies and popular culture (Robertson, 1997; Weber & Mitchell, 1995, 1999) that identify the teacher as one who is organized, always prepared with the right response. However, when the pre-service teacher arrives in the classroom despite plans and directions and the strong desire for success according to legend, the order is lost. As with any relationship, it is important to come prepared but also present, willing to learn, respond, accept, and reflect within the relational kaleidoscope otherwise known as the classroom. My/Self as Student Teacher As a teacher educator, my pedagogy has been significantly shaped by my experiences those as a student, a teacher, a daughter - the list and roles are likely infinite. However, I think one of the most influential positions, was my own experience as a student teacher. The picnic table shrouds anxiety Lines of individuals appetites insatiable Listening, stuff their mouths silenced as they wait for disconnected answers. My own student teaching experience was an absolute disaster. I started off well enough, eager to learn and try new things as I got to know the students in my third grade classroom. My supervisor prepared us with lists and took us on tours of other schools so that we could see what the ideal classroom looked like. Dale (2004) remarks, Learning to teach involves being attuned to particular narratives, learning to do what teachers (should) do, learning to see, think, feel, and talk as teachers (should) (p. 72). This certainly reflects my own experience student teaching: we were inundated with the shoulds and even at times the hows. However, I forgot to see where I fell into the equation; when failure came, I was left not knowing what to do. After my students had left the classroom for art, my cooperating teacher quickly shut the door and said we need to talk.

MacKenzie: Circles of (Im)perfection

My body shakes premonition strong flight seems inevitable I wait In my waiting, she quickly told me she need to get something off her chest, for her own health and with this came the deluge of her frustrations with my performance. I am sure some of it may have been productive; however all I heard was: Disconnected Failure Not one of us We dont want you unless you act like we act My response was quick, and perhaps not what she expected as I rushed out of the room, without expression, holding back my tears until I could find a private space to be with my feelings. I believed at the time, to respond emotionally would have been further failure and I just could not do this. I remember feeling so alone and wanting desperately for my supervisor to come to my rescue. Yet she was not prepared, instead she suggested she come observe my teaching, give me some feedback/tips regarding that. This was not her fault, she had been a practicing teacher who was trying something new ; having taught for 20 + years within an institution that silences emotion in favor of production, she may very well have had no idea how to help me. In fact, I am sure that my emotionality during the experience scared her; it was not rational or fixable. I remember in those following two weeks before I finally decided to leave my student teaching placement - forgoing certification, I had felt so alone. I could not talk about my experience or my feelings, whether they be regarding failure, success, or confusion and thus I simply walked away, never stopping to fully reflect upon the experience. After some time as a classroom teacher as well as a teacher educator, I have now had a great many opportunities to reflect on the experience. I know I was young, immature, and I responded rashly, but I also believe that perhaps if I had, had the opportunity to look deeply at myself, the events that were going on in my life both inside and outside the classroomI might have been able see value in the work I was doing and possibility for growth. And it is

IJEA Vol. 12 No. 7 - http://www.ijea.org/v12n7/

from this position -- that which seeks to honor the whole, fragmented, messy individual who exists across multiple planes, that I shape my practices as a teacher educator, especially when it comes to the ways I organize our weekly student teaching seminar. What Happens in Community Recognizing the feelings of isolation and discomfort that often arise for student teachers as they negotiate between the spaces of being a student and being a professional, I believe it is important to start the student teaching seminar from where they are -- drawing on the memories that shape them, the dreams they hold on to, the love they experience, the self they see in the mirror. Inviting them to first enter into a space of self reflection, then, into a dialogue of communal reflexivityit is my intention to open space for growth and a sense of community. The First Class (Seminar Meeting) On Wednesday, August 26th, 8 eager young women gathered around a seminar table in the biology building. It was our first meeting and everyone was nervous. I had taught two of the girls the previous semester, but the other six were familiar only in name. I had no idea what to expect from them and they had no idea what to expect from me. What I did know was that the women that entered my classroom were complex individuals who wanted to know what they needed (should) to do in order to achieve success. After a day of reviewing the syllabus, identifying the qualities of a good teacher, reviewing what it means to understand, reflecting the big ideas they might draw on from previous courses, and discussing the concept of professionalismstudents were ready to spend two days in the classroom, just observing. They arrived back on the fourth day of our seminar eager to share their observations and their thoughts about what they might bring to the classroom and I certainly gave them some time to do this. After some time for discussion, I stated the following, You talked about what you will bring to the classroom and I am sure those of you who have had class with me, remember that as a teacher that you are never neutral. Not only will this experience be one of professional growth for you, but it will also be a time where you will bring in every aspect of who you are into the space of the classroom and you will grow. Who you are, who we are and the experiences that shape us are important to acknowledge and embrace.

MacKenzie: Circles of (Im)perfection

At this moment, I shared my own I AM poem: I am long hot evenings catching fireflies along the lakeside, nights full of laughter and the shattering of plates in anger I am daughter, caretaker, confident, a little girl who knows too many secrets white and privileged becoming aware of truths and letting go of longings I am the wind whipping along the north sea of Scotland imagining what might someday be I am a teacher mourning the loss of a child angry because no one could save him committed to valuing independence and exploration daughter of parents who no longer speak to each other a one time church goer who now spends Sunday mornings kayaking along the river with the man I love I am a fighter A writer Artist A want to be mother Searching for what exists in a moment Remembering the visions of a past A woods walker journeying new paths with my blue eyed brown eyed dog I am a yogini moving with breath across the mat trying to let go trying to be present while sometimes watching too much television I am a woman who sometimes forgets to lock her door at night and wakes up to the imagined (or real) predatorial noise of a stalker and cant fall back to sleep I am the one who obsesses over the potential for failure and will take hours to prepare for just a few minutes

IJEA Vol. 12 No. 7 - http://www.ijea.org/v12n7/

10

I am Smithport and Catskill, Boonville and Mechanicville, Laconia and Concord Private school and public school always searching for something better and at one time never satisfied I am today and tomorrow and yesterday Wheeling across my consciousness always I am becoming someone new but slightly old Upon the conclusion of reading the poem, I did not ask for a response, rather, I invited students to create their own I AM poems, providing no other direction except to write without judgment (Goldberg, 1990) and to focus more upon their own subjectivity/experience as opposed to form. After some time when the students had finished the writing, I invited them to switch their papers and read the poems created by their peers, circling or underlining those words or phrases that seemed to resonate for them. At first, the students were reluctant, anticipating evaluation; however I reminded them that they were simply reading the poems to find those elements that they felt a connection to. I then asked them to pass the marked pages of these poems to me, so that I might create a We Are found poem, created from the words/phrases that they identified. We are always the same person inside change a displaced circle consistent and controlling the pushover, softie in a room full of laughter and secrets desperate to see the good in people leaving me vulnerable passionate with an open heart The guilt ridden dreamer A keeper of routines, traditions, and memories sick of people telling me teaching is easy responsibilities, clich

MacKenzie: Circles of (Im)perfection

11

Anxious dancer in a fairytale scared of feeling wanting change A hopeful protector trying to find calm in failed events The sensitive one independent and faithful listening to struggles without judgement someone that others can turn to rely on wishing I could change decisions made in the past The introverted extrovert surrounded in the unknown learning, deserving with appreciation good, happiness, love in relationship with people who will make me better The respected one a perfectionist uncertain trying to please everyone patient and content second guessing myself my failure, my past wondering how experience, secrets, knowledge might change the person I have become fortunate and understanding wanting A wishful creator excited about the unknown I am we are Teacher

IJEA Vol. 12 No. 7 - http://www.ijea.org/v12n7/

12

That same afternoon, upon the completion of the poem activity, I invited students to break into groups, to choose images that they felt answered (whether metaphorically or in a more concrete fashion) the following questions: What is teaching? How do you define yourself as a teacher? How do your experiences inside and outside the classroom shape you as a teacher? What is important to keep in mind when you enter the classroom? What might be important to forget (are there things)? How are your actions as a teacher shaped by others? What is the value of knowing yourself and how can this be beneficial to your teaching identity and educational practices?

I then asked them to identify those ideas that were more central to their identity as teachers and those that seemed to play some role in informing their practice and understanding, but were perhaps not as important. My original intention was then to have them create a community mandala where they placed the most important concepts in the center and then branched out from there; however, students were deeply engaged in the process and we were running out of time and therefore, I asked them to label where they thought the images should go and from their direction, I pieced together our community mandala, interweaving the We Are poem created from the words they chose when they read one anothers I Am poems. While made up of images and words chosen by the students, ultimately the mandala that evolves is a poetic and visual interpretation of the choices made by my student teachers. I can identify with Cahnmann (2003) when she shares about her own interpretation of fieldnotes, remarking: My identity as both a poet and researcher gave me license to adjust what is true (with a lower case t) in the original and the detailed accuracy to capture Truth (with a capital T), that is the depth of feeling and music in the original situation (p. 33).

As I pieced together the images of the mandala, once again I was engaging with poetic inquiry, this time in a visual sense. The images in the mandala reflected the conflict that is articulated within their We Are poem. Through their choice of images, it was clear that there was a longing for comfort, love (both giving and receiving) that played a large role in relationship to shaping their perceptions

MacKenzie: Circles of (Im)perfection

13

of practice and their desire to teach. However, also present was confusion as student teachers tried to find realistic images of what they believed. They cut out many smiling faces of beautiful children in an almost passive attempt to arrive at the desired outcome rather than to enter into the (im)perfect possibilities of the experience. They also struggled when it came to determining which images belonged in the center, as most important to their identity and practice. The images that were finally chosen for the center were more ambiguous, abstract and symbolic, offering more apparent points of entry for interpretation, allowing in a sense for no choice to be wrong. The presentation of the mandala is messy, as images and text overlap and intersect; something I believed was an important representation of my own experience as well as a reality that I felt was important for my students to acknowledge. Messiness speaks amidst anticipation unconditional love distant in this moment we wait excited softly ambivalent yearning for linearity between abstract impatience Irwin (2003) intimates that an aesthetic way of knowing appreciates the awkward spaces existing between chaos and order, complexity and simplicity, certainty and uncertainty, to name a few dialectical relationships (p.63). Through the creation of and engagement with poetry, choosing the images for the mandala, and then responding to the image, the student teachers were able to see experience not through a binary lens, but rather through a dialogical lens that invited a new awareness, recognition of being as both chaotic and orderly. It is my belief that it was the initial aesthetic, reflexive experience where students (rather uncomfortably) worked together to piece desire, experience, knowledge and expectation in relation to self and practice, that allowed for a space of acceptance to be created. Throughout the semester, students were asked to share their joys, sorrows, challenges, questions, and insights and slowly they worked through the discomfort to emerge as critically aware and reflexive practitioners that valued themselves and one another, as well as the ambiguity of

IJEA Vol. 12 No. 7 - http://www.ijea.org/v12n7/

14

their practice. While there were moments of embarrassed confessionals, the students accepted one anothers limitations and began to reflect thoughtfully rather than dismiss or hide in shame over the messiness of practice. While our community developed early on, it continued to grow and by the end of the semester, it was clear that we were a community of learners who really cared about and loved one another. It was this same caring and awareness that moved beyond the boundaries of our seminar into each classroom where a student teacher taught. The Final Class (Seminar Meeting) On the last day of the student teaching seminar, I asked students to write down what they had learned from the experience - perhaps returning to the weekly insights we made note of following our sharing of joys, sorrows and challenges; I encouraged them to write their thoughts using a haiku format so that they might better focus on the big ideas. From their words, we pieced together a modified renga. A renga is a collaborative poem of sorts, usually starting with the traditional 5/7/5 pattern of haiku, as one stanza (haiku) is created, other individuals create their own stanzas to join the poem. I began the poem with the first stanza and then left the space open for students to post their own poetic responses summarizing their experience, building upon what I had begun in the first stanza. Wrapped in emotion we become the beginning and the end, knowing We are all learners helping others learn with us loving what we do Meeting new children watching them grow in learning knowing we matter Not every student will learn the lessons you teach just try; dont give up We will make mistakes, but by learning from them we will become better

MacKenzie: Circles of (Im)perfection

15

We are capable touch a life, support them always time, tears, fear, love, strength We will always be learning growing with our students Walking in nervous days of endless learning leaving a teacher Children have power to change and inspire you they have touched our lives The earth breathes the we children and adults sharing, learning, growing, wise It was evident, that even within ambiguity and (im)perfection, they had found peace and a capacity to truly love their students, becoming present and open to learning. Endings and Beginnings Britzman (1991) notes, Practice, time, dialogue, and creativity are the ingredients for becoming a teacher and the sources of revitalization (p. 182). My student teachers are graduating today, with that diploma in hand they are heading out into the world, into the classroom as complex and knowledgeable individuals. However, this day is only a moment, a piece of the mosaic that will become their life as a teacher. The arrival quick unmistakable (un)remarkable becoming Pardoned for our humanness a body organs succinctly speaking to one another A song across (dis)cord and desire Each moment an interaction a messy possibility

IJEA Vol. 12 No. 7 - http://www.ijea.org/v12n7/

16

Perhaps on this day, as in the future they will feel no need to wear the mask of all-knowing and perfection (Sameshima, 2008, p. 8), but rather may they relish in their (im)perfection, aware that it is the chaos of the living being, the messiness of knowing and not knowing that allows them to love and learn in relationship, to be present to possibility. References Ayers, W. (1993). To teach: The journey of a teacher. New York: Teachers College Press. Boler, M. (1999) Feeling Power: emotions and education. New York: Routledge. Brady, I. (2009). Forward. In M. Prendergast, C. Leggo & P. Sameshima (Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences (pp. xi-xvi). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers. Britzman, D. (1991) Practice Makes Practice. Albany: State University of New York Press. Cahnmann, M. (2003). The craft, practice, and possibility of poetry in educational research. Educational Researcher, 32(3), 29-26. Dale, M. (2004). Tales in and out of school. In D. Liston, & J. Garrison. (Eds.), Teaching, Learning, and Loving. (pp. 65-79). New York: Routledge Falmer. Davis, B. & Sumara, D. (2007). Complexity science and education: Reconceptualizing the teachers role in learning. Interchange, 38(1), 53-67. Goldberg, N (1990). Wild Minds: living the writers life. New York: Bantam Books. Grumet, M. (1988). Bitter Milk. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. Irwin, R. (2003). Toward and aesthetic of unfolding in/sights through curriculum. Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies, 1(2), 63-78. Leggo, C. (2006). Learning by heart: A poetics of research. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, (Winter), 73-96. Leggo, C. (2008). The ecology of personal and professional experience: A poets view. In M. Cahnmann-Taylor & R. Siegesmund (Eds.), Arts-based research in education: Foundations for practice. (pp.89-97). New York: Routledge. Luce-Kapler, R. (2009). Serendipity, poetry, and inquiry. In M. Prendergast, C. Leggo & P. Sameshima (Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences (pp.75-78). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers. Palmer, P. (1998). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teachers life. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

MacKenzie: Circles of (Im)perfection

17

Robertson, J. (1997). Fantasy's confines: Popular culture and the education of the female primary schoolteacher. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue canadienne de l'ducation, 22(2), 123-143. Rossiter, A. (1997). Putting order in its place: Disciplining pedagogy. Curriculum Studies, 5(1), 29-38. Sameshima, P. (2008). Letters to a new teacher: A curriculum of embodied aesthetic awareness. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(2), 29-41. Trungpa, C. (1991). Orderly chaos: The mandala principle. Boston: Shambala. Weber, S., Mitchell, C. (1995). Thats funny, you dont look like a teacher. Washington DC: The Falmer Press. Weber, S., Mitchell, C. (1999). Reinventing ourselves as teachers: Beyond nostalgia. Washington DC: The Falmer Press.

About the Author Sarah K. MacKenzie is an Assistant Professor of Education at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where she mentors student teachers and teaches courses in literacy and educational foundations. Her current research explores arts-informed epistemologies and the ways and spaces in which pre-service teachers (co)write their identities as teachers.

International Journal of Education & the Arts

Editors

Margaret Macintyre Latta University of Nebraska-Lincoln, U.S.A. Christine Marm Thompson Pennsylvania State University, U.S.A.

Managing Editors

Alex Ruthmann University of Massachusetts Lowell, U.S.A. Matthew Thibeault University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, U.S.A.

Associate Editors

Jolyn Blank University of South Florida, U.S.A. Chee Hoo Lum Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Marissa McClure University of Arizona, U.S.A.

Editorial Board

Peter F. Abbs Norman Denzin Kieran Egan Elliot Eisner Magne Espeland Rita Irwin Gary McPherson Julian Sefton-Green Robert E. Stake Susan Stinson Graeme Sullivan Elizabeth (Beau) Valence Peter Webster University of Sussex, U.K. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, U.S.A. Simon Fraser University, Canada Stanford University, U.S.A. Stord/Haugesund University College, Norway University of British Columbia, Canada University of Melbourne, Australia University of South Australia, Australia University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, U.S.A. University of North CarolinaGreensboro , U.S.A. Teachers College, Columbia University, U.S.A. Indiana University, Bloomington, U.S.A. Northwestern University, U.S.A.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Collage ArticleDocument21 paginiCollage Articleapi-239517962Încă nu există evaluări

- A Tapestry of Teaching Navigating the Classroom JourneyDe la EverandA Tapestry of Teaching Navigating the Classroom JourneyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poetry for Education: Classroom Ideas That Inspire Creative ThinkingDe la EverandPoetry for Education: Classroom Ideas That Inspire Creative ThinkingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ontario Institute For Studies in Education/University of Toronto and Blackwell Publishing Are CollaboratingDocument12 paginiOntario Institute For Studies in Education/University of Toronto and Blackwell Publishing Are Collaboratinga9708Încă nu există evaluări

- Using Creativity and Grief To Empower My Teaching Evelyn Payne ELED 622 12/4/17Document19 paginiUsing Creativity and Grief To Empower My Teaching Evelyn Payne ELED 622 12/4/17api-316502259Încă nu există evaluări

- Always BecomingDocument14 paginiAlways Becomingapi-396348596Încă nu există evaluări

- The Art of Composition InstructionDocument7 paginiThe Art of Composition InstructionRyan Sergent - PayneÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Journey Towards Better Teaching Practices Within A Self Consciousness and Social Change FrameworkDocument6 paginiA Journey Towards Better Teaching Practices Within A Self Consciousness and Social Change FrameworkCarolina RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding What Students Know and Are Able To Do: Final Reflective EssayDocument5 paginiUnderstanding What Students Know and Are Able To Do: Final Reflective Essayapi-271071592Încă nu există evaluări

- Educ 629 Capstone Essay PughDocument8 paginiEduc 629 Capstone Essay Pughapi-625229084Încă nu există evaluări

- Teaching and Learning from Neuroeducation to Practice: We Are Nature Blended with the Environment. We Adapt and Rediscover Ourselves Together with Others, with More WisdomDe la EverandTeaching and Learning from Neuroeducation to Practice: We Are Nature Blended with the Environment. We Adapt and Rediscover Ourselves Together with Others, with More WisdomÎncă nu există evaluări

- LeblancannotatedbibDocument4 paginiLeblancannotatedbibapi-248626904Încă nu există evaluări

- The Courage To Teach: Parker J PalmerDocument3 paginiThe Courage To Teach: Parker J PalmercorinachiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Courage To TeachDocument3 paginiThe Courage To TeachRomeo Acero-Abuhan100% (1)

- READING 1.2 - Jehangir-2012-About - CampusDocument7 paginiREADING 1.2 - Jehangir-2012-About - Campusaryanrana20942Încă nu există evaluări

- Silence As Indicator of Engagement: Yolanda MajorsDocument3 paginiSilence As Indicator of Engagement: Yolanda MajorsAbhishek SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kyle Bjorem's Philosophy of Teaching WritingDocument1 paginăKyle Bjorem's Philosophy of Teaching WritingNicholas SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Humans in the Classroom: Exploring the lives of extraordinary teachersDe la EverandHumans in the Classroom: Exploring the lives of extraordinary teachersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principled Headship: A Teacher's Guide to the Galaxy (Revised Edition)De la EverandPrincipled Headship: A Teacher's Guide to the Galaxy (Revised Edition)Încă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4 KurikulumDocument6 paginiChapter 4 KurikulumYeri FalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- GED 8516 Leadership TRSL A - Dissertation ProspectusDocument17 paginiGED 8516 Leadership TRSL A - Dissertation ProspectusAmy HewettÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary of Chapter One: Be Active and Dramatic in Dialogue To Transform LearningDocument13 paginiSummary of Chapter One: Be Active and Dramatic in Dialogue To Transform LearningrerereÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heather Anne Trahan Teaching Philosophy Creating A CommunityDocument2 paginiHeather Anne Trahan Teaching Philosophy Creating A CommunitytrahanheatherÎncă nu există evaluări

- 05-06-2020 Executive Summary. Carolina RojasDocument7 pagini05-06-2020 Executive Summary. Carolina RojasCarolina RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spirituality and Pedagogy: Being and Learning in Sacred SpacesDe la EverandSpirituality and Pedagogy: Being and Learning in Sacred SpacesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Teaching Brain: An Evolutionary Trait at the Heart of EducationDe la EverandThe Teaching Brain: An Evolutionary Trait at the Heart of EducationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frank Mccourt'S Teacher Man: A Novel Approach To Teacher Learning and Professional DevelopmentDocument14 paginiFrank Mccourt'S Teacher Man: A Novel Approach To Teacher Learning and Professional DevelopmentKastriot AvdiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artistic and Creative LiteracyDocument45 paginiArtistic and Creative LiteracyRosé SanguilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Delicate Task: Teaching and Learning on a Montessori PathDe la EverandA Delicate Task: Teaching and Learning on a Montessori PathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art & PedagogyDocument12 paginiArt & PedagogyDinesh RaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Class to Community: A collection of cooperative activities for the ELT classroomDe la EverandFrom Class to Community: A collection of cooperative activities for the ELT classroomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Using Metaphors in Education: Studied Metaphors in Our Education, But Even Without Realizing It, Those of Us InvolvedDocument4 paginiUsing Metaphors in Education: Studied Metaphors in Our Education, But Even Without Realizing It, Those of Us InvolvedSonia MiminÎncă nu există evaluări

- Awakening The Reader in Every Child, Thoughtfully Outlines An Approach That I Hope To Emulate With My FutureDocument2 paginiAwakening The Reader in Every Child, Thoughtfully Outlines An Approach That I Hope To Emulate With My Futureapi-316320676Încă nu există evaluări

- Empathy in The Writing ClassroomDocument3 paginiEmpathy in The Writing Classroomapi-395950323Încă nu există evaluări

- Take Five! for Language Arts: Writing that builds critical-thinking skills (K-2)De la EverandTake Five! for Language Arts: Writing that builds critical-thinking skills (K-2)Încă nu există evaluări

- Small Shifts: Cultivating a Practice of Student-Centered TeachingDe la EverandSmall Shifts: Cultivating a Practice of Student-Centered TeachingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artbased PedagogyDocument7 paginiArtbased PedagogyElena C. G.Încă nu există evaluări

- Liston The Lure of Learning in TeachingDocument28 paginiListon The Lure of Learning in TeachingDaniel NunnehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inclusive Classroom CompositionDocument6 paginiInclusive Classroom CompositionAnna FreemanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organic Creativity in the Classroom: Teaching to Intuition in Academics and the ArtsDe la EverandOrganic Creativity in the Classroom: Teaching to Intuition in Academics and the ArtsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Action Research ProjectDocument48 paginiAction Research Projectapi-604646074Încă nu există evaluări

- Relationships and BehaviourDocument34 paginiRelationships and BehaviourCarol RodriguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notice That They Were Dominating The Discussion? What Else Was I Missing?Document11 paginiNotice That They Were Dominating The Discussion? What Else Was I Missing?api-335106108Încă nu există evaluări

- Somatics and Revisioning PedagogyDocument25 paginiSomatics and Revisioning Pedagogyluisrobles1977Încă nu există evaluări

- Schooling Learning Teaching: Toward Narrative PedagogyDe la EverandSchooling Learning Teaching: Toward Narrative PedagogyÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Engaged Learner: a Pocket Resource for Building Community SkillsDe la EverandAn Engaged Learner: a Pocket Resource for Building Community SkillsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated Bib PDF Final2Document6 paginiAnnotated Bib PDF Final2api-289511293Încă nu există evaluări

- ELT J 1999 Thornbury 4 11Document8 paginiELT J 1999 Thornbury 4 11mikimun100% (1)

- The Luminescent Odyssey: A Teacher's Gift of LightDe la EverandThe Luminescent Odyssey: A Teacher's Gift of LightÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reclaiming Literacy Classrooms Through Critical Dialogue: CommentaryDocument7 paginiReclaiming Literacy Classrooms Through Critical Dialogue: Commentaryalice nieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gaily-Coloured Creatures: Philosophy with children from Primary SchoolDe la EverandGaily-Coloured Creatures: Philosophy with children from Primary SchoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philophies of EducationDocument9 paginiPhilophies of EducationMitch TisayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exploring Education Through Phenomenology: A Review of Gloria Dall'Alba's (Ed.) Diverse ApproachesDocument11 paginiExploring Education Through Phenomenology: A Review of Gloria Dall'Alba's (Ed.) Diverse ApproachesAgustín PalomarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hardt, Michael & Antonio Negri - Declaration (2012)Document98 paginiHardt, Michael & Antonio Negri - Declaration (2012)Jernej75% (4)

- Annie SprinkleDocument4 paginiAnnie SprinkleAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fiery Furnace: Performance in The ' 80s, Warinthe' 90sDocument10 paginiThe Fiery Furnace: Performance in The ' 80s, Warinthe' 90sAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Storr Our GrotesqueDocument21 paginiStorr Our GrotesqueAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loud Ladies Deterritorialising Femininit PDFDocument18 paginiLoud Ladies Deterritorialising Femininit PDFAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fiery Furnace: Performance in The ' 80s, Warinthe' 90sDocument10 paginiThe Fiery Furnace: Performance in The ' 80s, Warinthe' 90sAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jean Fisher On Carnival Knowledge, "The Second Coming" - Artforum InternationalDocument5 paginiJean Fisher On Carnival Knowledge, "The Second Coming" - Artforum InternationalAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument23 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument17 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loud Ladies Deterritorialising Femininit PDFDocument18 paginiLoud Ladies Deterritorialising Femininit PDFAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument25 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Users Guide To The ImpossibleDocument31 paginiUsers Guide To The ImpossibleMsaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fantasies of Participation The SituationDocument29 paginiFantasies of Participation The SituationAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument20 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument24 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument24 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument24 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument27 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument24 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument29 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument24 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument18 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument38 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument31 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument6 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument21 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument26 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inspiring Creativity in Urban School Leaders: Lessons From The Performing ArtsDocument23 paginiInspiring Creativity in Urban School Leaders: Lessons From The Performing ArtsAndreia Miguel100% (1)

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument20 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument4 paginiInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Xander and The Rainbow-Barfing Unicorns: Includes The Following TitlesDocument2 paginiXander and The Rainbow-Barfing Unicorns: Includes The Following Titlesjiyih53793Încă nu există evaluări

- "The Inner Circle" - Prologue, Winter 2010Document2 pagini"The Inner Circle" - Prologue, Winter 2010Prologue MagazineÎncă nu există evaluări

- NarrativepdfDocument82 paginiNarrativepdfapi-267676063Încă nu există evaluări

- Sariyannis - of Ottoman Ghosts, Vampires and Sorcerers PDFDocument31 paginiSariyannis - of Ottoman Ghosts, Vampires and Sorcerers PDFMegadethÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cinderella Story As Example of Narrative TextDocument2 paginiCinderella Story As Example of Narrative TextHikmatul Maghfiroh100% (1)

- Annotated Bibliography of RLSDocument4 paginiAnnotated Bibliography of RLSdaltonshanebagleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Re-Imagining HekateDocument13 paginiRe-Imagining Hekateljudmil100% (1)

- PDFDocument63 paginiPDFShakir TantryÎncă nu există evaluări

- FA 48D 01 - Auteur TheoryDocument6 paginiFA 48D 01 - Auteur TheoryanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Snowflakes at Pemberley A Pride and Prejudice Variation by Jennifer KayDocument142 paginiSnowflakes at Pemberley A Pride and Prejudice Variation by Jennifer KayBautista GentileÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercises On Relative PronounsDocument2 paginiExercises On Relative PronounsPhan NgocÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Bible Is Our Spiritual FoodDocument2 paginiThe Bible Is Our Spiritual FoodMady Chen100% (1)

- The Coen Brothers - Two American FilmmakersDocument189 paginiThe Coen Brothers - Two American FilmmakersEnriqueta22Încă nu există evaluări

- Topic 3 Objectives:: Activity ADocument3 paginiTopic 3 Objectives:: Activity AJai GoÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV Cover Letter Template DownloadDocument8 paginiCV Cover Letter Template Downloadswqoqnjbf100% (2)

- My Last Duchess Summary .Document8 paginiMy Last Duchess Summary .Tanveer AkramÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romeo and Juliet William ShakespeareDocument124 paginiRomeo and Juliet William Shakespearerado011100% (1)

- Litvin On HamletDocument20 paginiLitvin On HamlettranslatumÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of English Translations of Holy QuranDocument7 paginiHistory of English Translations of Holy QuranOmair Hamid EnamÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Q1 Module 1Document39 paginiEnglish Q1 Module 1Mary Glenda Ladipe83% (6)

- IhsanDocument3 paginiIhsanMd. Naim KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anglo Saxon Period FULLDocument34 paginiAnglo Saxon Period FULLAulia AzharÎncă nu există evaluări

- KUNDA, GUIDEON - Engineering Culture Control and Commitment in A High-Tech CorporationDocument4 paginiKUNDA, GUIDEON - Engineering Culture Control and Commitment in A High-Tech CorporationWlos MiriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Srimad Bhagavad Gita IntroductionDocument26 paginiSrimad Bhagavad Gita Introductionapi-25887671100% (1)

- Hearing Bachs PassionsDocument191 paginiHearing Bachs PassionsAnonymous fDlxv6Zq100% (1)

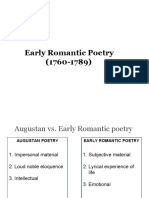

- 3 - Early Romantic PoetryDocument22 pagini3 - Early Romantic PoetryDestroyer 99Încă nu există evaluări

- Hawthorne Final PaperDocument23 paginiHawthorne Final PaperHeidi TravisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ted Hughes From Cambridge To Collected by Hughes, Ted Hughes, Ted Gifford, Terry Wormald, Mark Roberts, NeilDocument270 paginiTed Hughes From Cambridge To Collected by Hughes, Ted Hughes, Ted Gifford, Terry Wormald, Mark Roberts, NeilAmeen AmeenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese Mythology - An Introduction by Anne M. BirrellDocument268 paginiChinese Mythology - An Introduction by Anne M. BirrellMarlonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Goldenhand by Garth Nix - Longer ExcerptDocument27 paginiGoldenhand by Garth Nix - Longer ExcerptAllen & Unwin50% (2)