Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Civilazation and Capitalism 15th-18th Century. Volume 1 - Fernand Braudel - 0088

Încărcat de

Sang-Jin LimDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Civilazation and Capitalism 15th-18th Century. Volume 1 - Fernand Braudel - 0088

Încărcat de

Sang-Jin LimDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

88

The Structures o f Everyday Life

the next. Plague occurred in Amsterdam every year from 1622 to 1628 (the toll: 35,000 dead). It struck Paris in 1612, 1619, 1631, 1638, 1662, 1668 (the last).188 It should be noted that after 1612 in Paris the sick were forcibly removed from their homes and transferred to the Hpital Saint-Louis and to the maison de Sant in the faubourg Saint-Marcel.189 Plague struck London five times between 1593 and 1664-5, claiming, it is said, a total of 156,463 victims. Everything improved in the eighteenth century. Yet the plague of 1720 in Toulon and Marseilles was extremely virulent. According to one historian, a good half of the population of Marseilles succumbed190 The streets were full of half-rotted bodies, gnawed by dogs 1 9 1 The cycle o f diseases Diseases appear and alternately establish themselves or retreat. Some die out. This happened in the case of leprosy, which may well have been conquered in Europe in the fourteenth or fifteenth centuries by draconian isolation measures. (Today, strangely enough, lepers at large never spread infection.) It was also true of cholera, which disappeared from Europe during the nineteenth century; of smallpox, which seems to have been eliminated for good during recent years; and it may be true of tuberculosis and syphilis, which are now in retreat before the miracle of antibiotics. One cannot, however, make any definite claims for the future, because syphilis is said to be reappearing today with some virulence. This had also been true of plague: after a long absence between the eighth and the fourteenth century, it broke out violently as the Black Death in 1348, ushering in a new plague cycle which did not die out until the eighteenth century.19 2 In fact these virulent attacks and retreats might have originated from the fact that humanity had lived behind barriers for so long, dispersed, as it were, on different planets, so that the exchange of contagious germs between one group and another led to catastrophic surprise attacks, depending on the extent to which each had its own habits, resistance or weakness in relation to the patho genic agent concerned. This is demonstrated with amazing clarity in a recent book by William H. MacNeill.193 Ever since man escaped from his primitive brutishness and came to dominate all other living creatures, he has exerted over them the macroparasitism of the predator. But he is at the same time constantly attacked and besieged by minute organisms - germs, bacilli and viruses - and is thus a prey to microparasitism. Is this mighty struggle at some deep level the essential history of mankind? It is perpetuated by linked chains of living beings: the pathogen which may, under certain circumstances survive independently, usually passes from one living organism to another. Man, who is one, but not the only target of this continual bombardment, adapts himself, secretes anti bodies and may arrive at an acceptable equilibrium with these foreign creatures that live with him. But the process of adaptation and immunity takes time. If some pathogen escapes from its biological niche and is unleashed on a hitherto

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Crying of Lot 49: Sunshine or ?Document1 paginăThe Crying of Lot 49: Sunshine or ?Sang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sweet Sweetback's Badasssss Song. The Watts Festival, Meanwhile, BroughtDocument1 paginăSweet Sweetback's Badasssss Song. The Watts Festival, Meanwhile, BroughtSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0078 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0078 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0075 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0075 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0063 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0063 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0081 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0081 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0080 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0080 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0072 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0072 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0082 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0082 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0079 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0079 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0074 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0074 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0076 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0076 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0067 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0067 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0066 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0066 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0073 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0073 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0056 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0056 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0071 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0071 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amerika, Echoed Adamic in Its Savage Satirization of Make-Believe LandDocument1 paginăAmerika, Echoed Adamic in Its Savage Satirization of Make-Believe LandSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Mercury Announced The Genre, Los Angeles Noir Passes IntoDocument1 paginăAmerican Mercury Announced The Genre, Los Angeles Noir Passes IntoSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0069 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0069 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0062 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0062 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- City of Quartz: The SorcerersDocument1 paginăCity of Quartz: The SorcerersSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0064 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0064 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0060 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0060 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0068 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0068 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noir Under Contract Paramount Gates, Hollywood: Sunshine or ?Document1 paginăNoir Under Contract Paramount Gates, Hollywood: Sunshine or ?Sang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hollers Let Him Go (1945), Is Noir As Well-Crafted As Anything by Cain orDocument1 paginăHollers Let Him Go (1945), Is Noir As Well-Crafted As Anything by Cain orSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - 0058 PDFDocument1 pagină1 - 0058 PDFSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- California Country Are Absent Los Angeles Understands Its Past, InsteadDocument1 paginăCalifornia Country Are Absent Los Angeles Understands Its Past, InsteadSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Myth of Opportunity Punctured in the City of QuartzDocument1 paginăThe Myth of Opportunity Punctured in the City of QuartzSang-Jin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- TESCO Business Level StrategyDocument9 paginiTESCO Business Level StrategyMuhammad Sajid Saeed100% (4)

- ACTIVITIESDocument2 paginiACTIVITIESNad DeYnÎncă nu există evaluări

- iOS E PDFDocument1 paginăiOS E PDFMateo 19alÎncă nu există evaluări

- Da Vinci CodeDocument2 paginiDa Vinci CodeUnmay Lad0% (2)

- Indirect Questions BusinessDocument4 paginiIndirect Questions Businessesabea2345100% (1)

- Privacy & Big Data Infographics by SlidesgoDocument33 paginiPrivacy & Big Data Infographics by SlidesgoNadira WAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Product BrochureDocument18 paginiProduct Brochureopenid_Po9O0o44Încă nu există evaluări

- B2B AssignmentDocument7 paginiB2B AssignmentKumar SimantÎncă nu există evaluări

- 30 - Tow Truck Regulation Working Document PDFDocument11 pagini30 - Tow Truck Regulation Working Document PDFJoshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aztec CodicesDocument9 paginiAztec CodicessorinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clifford Clark Is A Recent Retiree Who Is Interested in PDFDocument1 paginăClifford Clark Is A Recent Retiree Who Is Interested in PDFAnbu jaromiaÎncă nu există evaluări

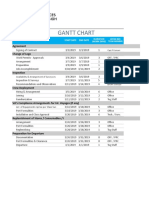

- Gantt Chart TemplateDocument3 paginiGantt Chart TemplateAamir SirohiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apg-Deck-2022-50 - Nautical Charts & PublicationsDocument1 paginăApg-Deck-2022-50 - Nautical Charts & PublicationsruchirrathoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- United BreweriesDocument14 paginiUnited Breweriesanuj_bangaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PHILIP MORRIS Vs FORTUNE TOBACCODocument2 paginiPHILIP MORRIS Vs FORTUNE TOBACCOPatricia Blanca SDVRÎncă nu există evaluări

- 03 A - Court-Annexed MediationDocument3 pagini03 A - Court-Annexed MediationXaye CerdenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- IVAN's TEST UAS 1Document9 paginiIVAN's TEST UAS 1gilangÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2016 AP Micro FRQ - Consumer ChoiceDocument2 pagini2016 AP Micro FRQ - Consumer ChoiceiuhdoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- ELECTRONIC TICKET For 4N53LY Departure Date 27 06 2023Document3 paginiELECTRONIC TICKET For 4N53LY Departure Date 27 06 2023حسام رسميÎncă nu există evaluări

- St. Edward The Confessor Catholic Church: San Felipe de Jesús ChapelDocument16 paginiSt. Edward The Confessor Catholic Church: San Felipe de Jesús ChapelSt. Edward the Confessor Catholic ChurchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apgenco 2012 DetailsOfDocuments24032012Document1 paginăApgenco 2012 DetailsOfDocuments24032012Veera ChaitanyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- XTRO Royal FantasyDocument80 paginiXTRO Royal Fantasydsherratt74100% (2)

- Shareholding Agreement PFLDocument3 paginiShareholding Agreement PFLHitesh SainiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cecilio MDocument26 paginiCecilio MErwin BernardinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- All About Form 15CA Form 15CBDocument6 paginiAll About Form 15CA Form 15CBKirti SanghaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complex Property Group Company ProfileDocument3 paginiComplex Property Group Company ProfileComplex Property GroupÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ob Ward Timeline of ActivitiesDocument2 paginiOb Ward Timeline of Activitiesjohncarlo ramosÎncă nu există evaluări

- DefenseDocument18 paginiDefenseRicardo DelacruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amplus SolarDocument4 paginiAmplus SolarAbhishek AbhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fruits and Vegetables Coloring Book PDFDocument20 paginiFruits and Vegetables Coloring Book PDFsadabahmadÎncă nu există evaluări