Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Submergence of Vital Root For Preservation of Residual Ridge

Încărcat de

Faheemuddin MuhammadTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Submergence of Vital Root For Preservation of Residual Ridge

Încărcat de

Faheemuddin MuhammadDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Vol 10, No 3, 2012 259

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

T

he major objective of any prosthetic rehabilita-

tion is to preserve remaining natural teeth and

tissues, which includes residual ridge preservation

in the fabrication of the complete dental prosthe-

sis. The measures taken by the prosthodontist in

reducing the forces transmitted to the residual al-

veolar ridge are the use of the selective pressure

impression technique, incorporation of compensa-

tory curves, achievement of balanced occlusion,

periodic check-ups, relining and rebasing if and

when required, making new dentures if necessary

and using of soft reliners. However, still the well-

documented fact remains that once the teeth are

lost, there is a continuous, irreversible process of

residual ridge resorption, and it becomes diffcult to

retain and stabilise complete dentures (Klemetti,

1996).

Submergence of Vital Roots for the Preservation

of Residual Ridge: A Clinical Study

Anil Sharma

a

/Sukhvinder Singh Oberoi

b

/Sudhanshu Saxena

c

Purpose: To test the value of submerging vital roots for the preservation of the residual ridge.

Materials and Methods: The study sample consisted of 10 patients whose bone height on both submerged and control

sites was measured with the help of OPG tracings and the use of grids, from the immediate post-operative period to 3

months, 6 months and 9 months post-operatively. Statistical analysis was performed using the t-test and one-way ANOVA.

Results: The amount of bone loss was signifcantly greater in the control area in comparison to the submerged area from

the immediate post-operative period to 3 months, 6 months and 9 months post-operatively.

Conclusion: Although the retained roots do not prevent the resorption of residual ridge, they aid in decreasing the resorp-

tive pattern, thereby preserving the residual ridge to some extent. This may be an expedient and inexpensive way to

preserve residual ridge, requiring minimal specialised training.

Key words: prosthetic factors, residual ridge, surgical technique, vital roots

Oral Health Prev Dent 2012;10: 259-265 Submitted for publication: 04.03.11; accepted for publication: 08.06.11

a

Professor and Head, Department of Prosthodontics, I.T.S Dental

College, Hospital and Research Centre, Greater Noida, India.

b

Senior Resident, Department of Public Health Dentistry, Maulana

Azad Institute of Dental Sciences, New Delhi, India.

c

Senior Lecturer, Department of Public Health Dentistry, Peoples

Dental College and Hospital, Bhopal, India.

Correspondence: Professor Anil Sharma, Department of Prosthodon-

tics, I.T.S Dental College, Hospital and Research Centre, Greater Noi-

da, India. Tel: +91-098-1120-6062. Email: drsharmaanil@gmail.com

In recent years, the dental profession has ex-

tended the concept of preventive dentistry in re-

movable prosthodontics by the use of overden-

tures. This method of treatment preserves the

residual ridge by retaining periodontically compro-

mised teeth which, although they cannot be used

as removable partial denture (RPD)/ fxed dental

prosthesis (FDP) abutments, are reduced to obtain

a satisfactory crown-root ratio to support remova-

ble dentures (Brewer, 1975).

Fractured roots and retained root studies were

probably the genesis for the submerged root con-

cept (Johnson and Jensen, 1997; Rodd et al,

2002). Various studies of roots remaining after in-

complete exodontia showed that nearly all such

roots remained vital and asymptomatic (Simpson,

1959; Herd, 1973; Glickman, 1974).

Clinical reports suggest that vital root retention

may be an alternative method to conventional over-

denture and implant treatment, one which also ap-

pears to retard the resorption of residual ridge

(Mead, 1929; Graver et al, 1978; Graver et al,

1979; Dravid, 1980; Graver and Muir, 1983;

Hughes et al, 1991). By maintaining the natural

tooth root, a greater amount of surrounding tissue

may also be preserved. Thus, the root submer-

gence technique also maintains the natural attach-

Sharma et al

260 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

ment apparatus of the tooth at the pontic site,

which in turn allows for complete preservation of

the alveolar bone frame and assists in creation of

an esthetic result (Marinello and Potashnick, 1994;

Salama et al, 2007). Other studies have shown

that roots which are endodontically treated and

submerged are also acceptable (Howell, 1970; Wal-

lace et al, 1994; Harper, 2002; Hiremath et al,

2010), but this entails extra expense for the pa-

tient and more clinical time than vital root submer-

gence, which is a simple clinical procedure that can

be carried out by an average dental surgeon in his/

her own clinic (Fareed, 1989).

The overall purpose of this study was to test the

value of submerging vital roots for the preservation

of residual ridges. This was accomplished by meas-

uring the amount of bone height in the submerged

and control sites and comparing the amount of

bone loss from the immediate post-operative period

to 3 months, 3-6 months, 6-9 months and the total

amount of bone loss after 9 months.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was done at the K.L.E. Societys Insti-

tute of Dental Sciences, Belgaum, Karnataka, In-

dia. The study sample consisted of 10 patients,

seven males and three females, with an age range

of 4060 years.

The study was performed by a single investigator.

The intra-examiner reliability was calculated by du-

plicate measurements and was found to be 87%.

For the uniform interpretation of the results, the av-

erage of the 2 measurements was taken.

There was one root per patient for control and

submerged sites, except for one patient who had 2

roots, so that the fnal data analysed consisted of

11 readings. The proposed treatment procedures

including possible complications were explained

and discussed with each patient. Informed written

consent was obtained from each patient before

starting the study.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were included if they: were scheduled to

receive complete dentures (maxillary and mandibu-

lar), having isolated natural teeth between the 2nd

premolars on either side; were partially edentulous

with teeth recommended for extraction which were

not suitable for use as FDP or RPD abutments, but

suitable for the proposed vital root retention; lacked

signifcant medical problems that may have compli-

cated the surgical procedure or interfered with the

post operative management.

The inclusion criteria for teeth were as follows:

no more than 1 mm horizontal mobility; periosteum

lacking infrabony pockets which could not be treat-

ed or reduced; suffcient healthy mucocogingival

tissue present for fnal closure of the surgical site;

supporting alveolar bone equal to approximately

one-third of the length of the total root length; car-

ies free and asymptomatic.

Study design

A split-mouth design was chosen one of the sides

with a retained root stump was taken as the sub-

merged site, and the contralateral side where the

root stump was removed was chosen as the control

site. On the submerged side, the roots were sub-

merged by raising the faps, and on the control side,

the roots were extracted as a part of the study.

Thus, the control site became edentulous because

of the extraction of the root stump.

Surgical procedure

Each patient was pre-medicated with oral antibiot-

ics one day before the surgical procedure and con-

tinued for 4 days (Cap. Amoxycillin, 500 mg, 3

times a day for 5 days). The patient was scrubbed

and pre-procedural hexidine mouthwash was given

to decrease the oral bacterial fora. Local anaesthe-

sia was administered to the patient, and an internal

bevel incision was made apical to the free gingival

margin and was directed to an area at or near the

crest of alveolar bone.

A buccal fap was elevated and subgingival calcu-

lus and granulomatous tissue were removed with a

spoon excavator. Using a straight diamond bur (No.

0.081), the selected teeth were sectioned horizon-

tally at the residual bone level. The confrmation of

pulp vitality was made by observing bleeding from

the pulp chamber.

Subsequently, using a large round diamond bur

(No. 0.010), the roots were ground 24 mm below

the residual ridge level and then fattened by a large

inverted cone bur (No. 0.006). All sectioning and

rounding procedures were carried out under con-

stant irrigation with physiological saline.

Sharma et al

Vol 10, No 3, 2012 261

The sharp bony margins were smoothed with the

help of a bone fle. A periosteal releasing incison

was made at the depth of the vestibule and the fap

was advanced towards the lingual mucoperiostium.

The incison line was closed with 3.0 black silk su-

ture in a horizontal mattress.

Post-operatively, the patients were asked to con-

tinue with the antibiotics for four days and take an-

algesic antinfammatory drugs as needed. The pa-

tients were also advised to take B-complex capsules

and use hexidine mouthwash for 4 weeks post-op-

eratively. Patients were recalled after 24 h for a

check-up, the sutures were removed after 1 week

and the impressions were made for complete den-

tures after 8 weeks.

Denture technique

The prosthetic management of the patients in-

volved fabrication of the denture in a step-wise

manner using the standardised procedure to en-

sure a successful prosthesis. The denture was fab-

ricated 8 weeks after the submergence of roots on

the submerged site and extraction of the root

stumps on the control site.

Measurements

The technique for taking orthopantomogrammes

(OPG) was standardised. The OPGs were taken

using the standard equipment with the standard ex-

posure and standard exposure time. A grid was

placed over the tracings and stabilised with the

help of pins in the same position every time. Sub-

sequently, tracings were done.

The measurements of the bone height on the

submerged side and its contralateral (control) side

were made immediately post-operatively, and was

followed-up every 3 months until the last appoint-

ment at 9 months. The measurements were made

from the crest of the ridge to the inferior border of

the mandible in the lower arch and from the crest of

the ridge to the foor of nasal cavity in the upper

arch.

These reference points for measuring bone

height were taken because in an average patient

with no major medical problems, the compact bone

does not undergo any major changes. If there was

more than one root on the same side, then meas-

urements over each submerged root were made

and were divided by the number of submerged roots

to give a mean bone height of the submerged area.

Similarly, measurements of the control side were

taken after the extraction of the teeth, so that the

control side was edentulous. The bone loss was

calculated from the immediate post-operative

period to 3 months, 36 months, 69 months, as

well as the immediate post-operative period to 6

months and the immediate post-operative period to

9 months.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS

software version 16.0 and the mean bone height

per person per root was calculated. The t-test was

used to compare mean bone loss between the con-

trol and submerged groups at different time inter-

vals, and one-way ANOVA was used for comparison

at various intervals within the control and sub-

merged groups.

RESULTS

Table 1 depicts the bone height (in mm) of the indi-

vidual patients in detail along with the site. The

overall bone height of the submerged and control

area immediately post-operatively, at 3 months, 6

months and 9 months post-operatively showed no

signifcant difference at any of the intervals

(P > 0.05) (Table 2).

The difference in the amount of bone loss be-

tween the submerged and control area from the im-

mediate post-operative period to 3 months, 6

months and 9 months post-operatively was com-

pared using the unpaired t-test. There was signif-

cantly more bone loss in the control area in com-

parison to the submerged area from the immediate

post-operative period to 3 months, 6 months and 9

months post-operatively (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

The comparison of differences in the amount of

bone loss between the submerged and control are-

as from the immediate post-operative period to 3, 6

and 9 months post-operatively was done using one-

way ANOVA test. There was a signifcant difference

in the amount of bone lost from the immediate

post-operative period to 3 months, 6 months and 9

months post-operatively among both the submerged

and control areas (P < 0.05). (Table 4, Fig 1).

Additionally, comparison within the submerged

and control area at different intervals was done

using the Tukey HSD post-hoc test. In the sub-

Sharma et al

262 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

merged area, there was a signifcant difference in

the amount of bone lost from the immediate post-

operative period to 3 months and 6 months post-

operatively (P < 0.05), but there was no signifcant

difference from 3 months to 6 months post-opera-

tively (P > 0.05). In the control group, there was a

signifcant difference in the amount of bone lost

from the immediate post-operative period to 3

months and 6 months post-operatively as well as

from 3 months post-operatively to 6 months post-

operatively (P < 0.05) (Table 4, Fig 1).

The difference in the amount of bone lost from 3

to 6 months and 6 to 9 months among submerged

and control area was compared using the unpaired

t-test. There was signifcantly greater bone loss in

the control area in comparison to the submerged

area from 3 to 6 months and 6 to 9 months post-

operatively (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 3 Comparison of the difference in the amount of

bone lost in submerged and control area

Groups

Mean bone

loss (mm)

P-value

Immediately

post-operatively

to 3 months

Submerged 0.70.4

0.109

Control 1.10.7

Immediately

post-operatively

to 6 months

Submerged 1.50.6

0.013*

Control 2.30.7

Immediately

post-operatively

to 9 months

Submerged 2.10.7

0.001*

Control 3.30.8

* The mean difference is signifcant at the 0.05 level.

Table 2 Mean bone height of submerged and control

area

Groups

Mean bone

loss (mm)

P-value

Immediately

post-operatively

Submerged 27.98.0

0.858

Control 27.47.3

At 3 months

Submerged 27.38.0

0.769

Control 26.37.4

At 6 months

Submerged 26.47.9

0.682

Control 25.17.1

At 9 months

Submerged 25.97.8

0.572

Control 24.17.0

Table 1 Description of bone height of submerged and control area of the individual samples

Patient

Roots

submerged Submerged area (mm) Control area (mm)

Immediately

post-

operatively

3

months

6

months

9

months

Immediately

post-

operatively

3

months

6

months

9

months

1 11,12,13 18 17.6 17 17 18 17 16 15.5

2 33, 34, 35 35 34.6 33.6 33 34 33.5 32 31

3a 22, 23 24 23 22 21 23 21 20.5 19

3b 43, 45 34 33 31.5 31 31 29 27.5 27

4 33 31 31 30.5 29 31 30.5 29 27

5 34, 35 31.5 30.5 29.5 29 31 30 28.5 27

6 34, 35 41 40 39 38.5 40 38.5 37 36

7 34 32 31.5 31 31 31 30.5 29.5 29

8 33, 34, 35 26 25 24.5 24 25 24.5 23.5 22

9 23, 25 16 15 14.5 14 17 16.5 15.5 14.5

10 21, 22, 23 19 18.5 17.5 17 20 18 17 16.5

Sharma et al

Vol 10, No 3, 2012 263

Table 4 Difference in the mean amount of bone lost

among the submerged and control areas from immedi-

ately post-operatively to 3, 6 and 9 months

Intervals

Mean bone loss (mm)

Submerged area Control area

Immediately

post-operatively

to 3 months

0.70.4 1.10.7

Immediately

post-operatively

to 6 months

1.50.6 2.30.7

Immediately

post-operatively

to 9 months

2.10.7 3.30.8

ANOVA 17.842 27.824

P-value 0.000* 0.000*

Tukey post-hoc

HSD test

2>1 2>1

3>1 3>1,2

* The mean difference is signifcant at the 0.05 level.

Table 5 Difference in the amount of bone lost from 3 to

6 months and 6 to 9 months in submerged and control

area (in mm)

Mean (mm) P-value

From 3 to

6 months

Submerged area 0.80.3

0.013*

Control area 1.20.3

From 6 to

9 months

Submerged area 0.50.3

0.001*

Control area 1.10.5

* The mean difference is signifcant at the 0.05 level.

Fig 1Difference in the amount of bone lost between the submerged and control areas from immediately post-operatively to

3, 6 and 9 months (in mm).

Submerged Control Submerged Control Submerged Control

Immediately postoperative Immediately postoperative Immediately postoperative

to 3 months to 5 months to 9 months

M

e

a

n

B

o

n

e

L

o

s

s

(

i

n

m

m

)

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0

0.71

1.09

1.54

2.27

2.09

3.32

Sharma et al

264 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

DISCUSSION

For years, it has been axiomatic that all retained

roots should be removed since all were considered

to be pathological (Mead, 1929; Mead, 1954).

However, many patients have been found to have

retained roots where no clinical or radiographic ab-

normality is present. In fact, it is an interesting ob-

servation that in those patients in whom either the

roots were accidently left inside the bone due to

incomplete exodontias or purposely retained, the

resorption of alveolar bone around the roots is not

only decreased, but led to the formation of new

bone over the roots (Ground 1978a and b; von

Wowern and Winther, 1981).

A signifcant difference was seen in bone loss

between submerged and control sides, with more

bone loss over the control side, which may also be

attributed to the irregular edges of the bone left

after extraction. These edges are rounded off by

external resorption, leaving a high, well-rounded

ridge as compared to the submerged area, where

the alveolar bone is supported by the tooth roots

and has smooth bony margins, decreasing the re-

sorption in this area.

In general, the rate of reduction of the residual

ridge varies between different individuals and is

usually more rapid in the frst 6 months following

extraction. It was also seen that from 6 to 9 months,

the bone resorption continued in both the sub-

merged and control areas, but was greater on the

control side (1.05 0.52 mm) than on the sub-

merged side (0.45 0.27 mm). The total amount

of bone lost from the immediate post-operative

period to 9 months was greater on the control side

(3.32 0.75 mm) than on the submerged side

(2.09 0.66 mm). This shows that the reduction

of the residual ridge is chronic, progressive, irre-

versible and cumulative.

We observed a decrease in residual ridge resorp-

tion on the submerged side, which may be attribut-

ed to the presence of roots within the alveoli, which

continuously provide a physiological stimulus to the

bone. This resulted in a decrease in resorption as

compared to control side, where there is no physi-

ological stimulus to the bone due to absence of

roots. This decrease in the rate of resorption of the

residual ridge may also be due to the difference in

distribution of forces over the submerged and the

control sides.

However, there are certain problems related to

vital root submergence which should be addressed.

Murry and Adkins (1979) have suggested dividing

the post-operative clinical problems of vital root

submergence into two categories: problems related

to the surgical technique and problems related to

prosthetic factors. The surgical complications can

be due to improper surgical techniques, improper

sterilisation, use of insuffcient coolant, incomplete

debridement of the surgical site, failure to achieve

complete closure over submerged roots, incom-

plete removal of the crevicular epithelium or im-

proper rounding of the bony margins.

Longitudinal cephalometric studies have provid-

ed excellent visualisation of the gross pattern of

bone loss (Tallgren 1970; Weinmann and Sicher,

1955). The superimposition of the tracings of ceph-

alograms made in such studies clearly shows that

the reduction of the ridge occurs labially on the

crest and lingually. The rate of reduction and the

total amount of bone vary from individual to indi-

vidual, within the same individual at different times

and even at the same time in different parts of the

ridge. Similarly, there may be many anatomic, bio-

logical and metabolic factors that may also effect

reduction of the residual ridge (Weinmann and Si-

cher, 1955; Ortman, 1962). These changes are in

accordance with Wolffs law, which states that eve-

ry change in the function of the bone is followed by

defnite changes in internal architecture and exter-

nal shape (Wolff, 1892).

Craddock states that resorption of bone follow-

ing tooth extraction takes place in two phases. The

early resorption is part of the healing process and

takes place very rapidly. The second phase is the

inevitable resorption that goes on indefnitely (Crad-

dock, 1951). Thus, the retained roots do not pre-

vent the resorption of the residual ridge, but rather

aid in decreasing the resorptive pattern, thereby

preserving the residual ridge to some extent.

This may be an expedient and inexpensive way to

preserve the residual ridge, requiring minimal spe-

cialised training. Since both objective and subjective

fndings clearly indicate the signifcant benefts of

tooth root retention, even the extraction of the few

remaining natural teeth should be considered a seri-

ous decision. It enabled us to observe a sequence

of treatment for a number of otherwise condemned

teeth (Masterson, 1979; Graver and Fenster, 1980).

CONCLUSION

The success of submerged roots in preventing the

resorption of the residual ridge was dependent

upon proper surgical procedure, which leads to the

Sharma et al

Vol 10, No 3, 2012 265

proper closure of mucosa over the retained roots.

Problems related to prosthetic factors were over-

come by simply reducing the localised pressure

over the submerged roots.

Although residual ridge resorption is an irrevers-

ible process, the resorption can be minimised or

reduced with the help of vital root retention, which

aids in preserving the residual ridge to some extent

and is obviously preferable to the totally edentulous

ridge.

Further research work and detailed studies are

required in this feld to delineate the proper mecha-

nism and ways of preserving the residual ridge, as

well as to determine the effect of the submerged

root in preventing the residual ridge resorption.

REFERENCES

1. Brewer AA, Morrow RM. Over Dentures. St. Louis: C.V. Mos-

by, 1975.

2. Casey DM, Lauciello FR. A review of the submerged root

concept. J Prosthet Dent 1980;43:128.

3. Craddock FW. Prosthetic Dentistry, ed 2. St. Louis: C.V.

Mosby, 1951.

4. Fareed K, Khayat R, Salins P. Vital root retention: A clinical

procedure. J Prosthet Dent 1989;62;430434.

5. Glickman I, Pruzansky S, Ostrach M. The healing of extrac-

tion wounds in the presence of retained root remnants and

bone fragments. Am J Ortho Oral Surg 1974;33:263.

6. Graver DG, Fenster RK. Vital root retention in humans: A

fnal report: J Prosthet Dent 1980;43:368.

7. Graver DG, Fenster RK, Baker RD, Johnson DL. Vital root

retention in humans: A preliminary report. J Prosthet Dent

1978;40:23.

8. Graver DG, Fenster RK, Connole PW. Vital root retention in

humans: An interim report. J Prosthet Dent 1979;41:255.

9. Graver DG, Muir TE. The retention of vital submucosal roots

under immediate denture A surgical procedure. J Prosth

Dent 1983;50:753

10. Ground T, ONeal RB, Delrio CE, Levin MP. Submergence of

roots for alveolar bone preservation I. J Oral Surg 1978a;

45:803.

11. Ground T, ONeal RB, Delrio CE, Levin MP. Submergence of

roots for alveolar bone preservation II. J Oral Surg 1978b;

46:114.

12. Harper AK. Submerging an endodontically treated root to

preserve the alveolar ridge under a bridge a case report.

Dent Update 2002;29:200203.

13. Herd JR. The retained tooth root. Australian Dent J 1973;

18:125.

14. Hiremath HP, Doshi YS, Kulkarni SS, Purbay SK. Endodontic

treatment in submerged roots a case report. J Dent Res

Dent Clin Dent Prospect 2010;4:6468.

15. Howell F. Retention of alveolar bone by endodontic root

treatment. Seminario Anual Del Grupo de Estudios Dentacs

U.S.C. de Mexico, 23 May 1970.

16. Hughes KW, Schofeld JC, Alves ME, Bennett BT. Disarming

canine teeth on nonhuman primates using submucosal

vital root retention technique. Lab Anim Sci 1991;41:

128133.

17. Johnson BR, Jensen MR. Treatment of a horizontal root

fracture by vital root submergence: Dent Traumatol 1997;

13:248250.

18. Klemetti E. A review of residual ridge resorption and bone

density. J Prosthet Dent 1996;75:512514.

19. Marinello R, Potashnick SR. Root retention for immediate

implant replacement A case report. J Compendium

1994;42:834.

20. Masterson MP. Retention of vital submerged roots under

complete dentures: report of 10 patients. J Prosthet Dent

1979;41:12.

21. Mead SV. Residual Infections. Int J Ortho 1929;15:

11201125.

22. Mead SV. Oral Surgery, ed 4. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby, 1954.

23. Murray CG, Adkins KF. The elective retention of vital roots

for alveolar bone preservation: A pilot study. J Oral Surg

1979;37:650.

24. Ortman HR. Factors of bone resorption of the residual

ridge. J Prosthet Dent 1962;12:1962.

25. Rodd HD, Davidson LE, Livesey S, Cooke ME. Survival of

intentionally retained permanent incisor roots following

crown root fratures in children. Dent Traumatol 2002;18:

9297.

26. Salama M, Ishikawa T, Salama H, Funato A, Garber D. Ad-

vantages of the root submergence technique for pontic site

development in esthetic implant therapy. Int J Periodon

Restor Dent 2007;27:521527.

27. Simpson HE. Histological changes on retained roots. J Can

Dent Assoc 1959;25:287.

28. Tallgren A. Alveolar bone loss in denture wearer as related

to facial morphology. Acta Odont Scand 1970;28:251-270.

29. Von Wowern N, Winther S. Submergence of roots for alveo-

lar ridge preservation. Int J Oral Surg 1981;10:247250.

30. Wallace JA, Cerman JE, Jimenez J. Endodontic therapy and

root submersion of a an impacted canine A case report

and review of the root submergence concept. J Oral Surg

Oral Med Oral Path 1994;77:519.

31. Weinmann JP, Sicher H. Bone and Bones, ed 2. St. Louis:

C.V. Mosby, 1955.

32. Wolff J. Das Gesetz der Transformation der Knochen. Ber-

lin: 1892.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Single Visit Natural Tooth Pontic Bridge With Fiber Reinforcement RibbonDocument4 paginiSingle Visit Natural Tooth Pontic Bridge With Fiber Reinforcement RibbonDentalLearningÎncă nu există evaluări

- Broadrick Flag.Document5 paginiBroadrick Flag.Martin Eduardo Ruiz Lopez100% (1)

- Three-Dimensional Evaluation of Dentofacial Transverse Widths in Adults With Different Sagittal Facial Patterns PDFDocument10 paginiThree-Dimensional Evaluation of Dentofacial Transverse Widths in Adults With Different Sagittal Facial Patterns PDFSoe San KyawÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Evidence-Based System For The Classification and ClinicalDocument9 paginiAn Evidence-Based System For The Classification and ClinicalAna Maria Montoya GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Björk 1955 CRANIAL BASE DEVELOPMENTDocument28 paginiBjörk 1955 CRANIAL BASE DEVELOPMENTPauly JinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparison of Traditional RPE With Two Types of Micro I - 2019 - Seminars in OrtDocument9 paginiComparison of Traditional RPE With Two Types of Micro I - 2019 - Seminars in OrtOmy J. Cruz100% (1)

- Gummy Smile Correction With TadDocument8 paginiGummy Smile Correction With TadRockey ShrivastavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Three-Dimensional Comparison of Condylar Position Changes Between Centric Relation and Centric Occlusion Using The Mandibular Position Indicator. Utt 1995Document11 paginiA Three-Dimensional Comparison of Condylar Position Changes Between Centric Relation and Centric Occlusion Using The Mandibular Position Indicator. Utt 1995Fernando Ruiz BorsiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perioral Forces and Dental Changes Resulting From Lip BumperDocument9 paginiPerioral Forces and Dental Changes Resulting From Lip Bumpersolodont1Încă nu există evaluări

- Angle Orthod. 2015 85 5 881-9Document9 paginiAngle Orthod. 2015 85 5 881-9brookortontiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Temporomandibular Joint Spaces and Condylar Position - A CBCT StudyDocument6 paginiEvaluation of Temporomandibular Joint Spaces and Condylar Position - A CBCT StudyDr Yamuna Rani100% (1)

- The University Münster Model Surgery System For Orthognathic Surgery. Part I - The Idea BehindDocument6 paginiThe University Münster Model Surgery System For Orthognathic Surgery. Part I - The Idea BehindDr Mostafa FarahatÎncă nu există evaluări

- PAPER (ENG) - Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire For Detecting DysphagiaDocument5 paginiPAPER (ENG) - Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire For Detecting DysphagiaAldo Hip NaranjoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relationships of Sagittal Skeletal Discrepancy, Natural Head Position, and Craniocervical Posture in Young Chinese ChildrenDocument7 paginiRelationships of Sagittal Skeletal Discrepancy, Natural Head Position, and Craniocervical Posture in Young Chinese ChildrenTanya HernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 JMSCR PDFDocument6 pagini11 JMSCR PDFmilanmashrukÎncă nu există evaluări

- To Evaluate Whether There Is A Relationship Between Occlusion andDocument13 paginiTo Evaluate Whether There Is A Relationship Between Occlusion andSamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Habla ClaraDocument14 paginiHabla ClaraCristóbal Landeros TorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Setting Procedure of The Fully Adjustable SAM 3 Articulator PDFDocument4 paginiSetting Procedure of The Fully Adjustable SAM 3 Articulator PDFortodoncia 2018Încă nu există evaluări

- Growth - Principles and ConceptsDocument70 paginiGrowth - Principles and ConceptsPranaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indices / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental AcademyDocument77 paginiIndices / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental Academyindian dental academyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prosthetic Rehabilitation of Acquired Maxillofacial Defect Obturating Residual Oronasal Communication A Clinical Report 91 93Document3 paginiProsthetic Rehabilitation of Acquired Maxillofacial Defect Obturating Residual Oronasal Communication A Clinical Report 91 93Maqbul AlamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre-Prosthetic Surgery: Mandible: Ental Science - Review ArticleDocument4 paginiPre-Prosthetic Surgery: Mandible: Ental Science - Review ArticleAdrian ERanggaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Efficacy of Grafting Materials in Alveolar Ridge Augmentation - A Systematic ReviewDocument12 paginiClinical Efficacy of Grafting Materials in Alveolar Ridge Augmentation - A Systematic Reviewvanessa_werbickyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laser en OrtodonciaDocument7 paginiLaser en OrtodonciaDiana ElíasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pain ManagementDocument44 paginiPain ManagementSaherish FarhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treatment of Brodie SyndromeDocument25 paginiTreatment of Brodie SyndromeAdina Serban100% (1)

- Growth AssessmentDocument65 paginiGrowth Assessmentdr parveen bathlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8 - Maxillary Expansion in Nongrowing Patients. Conventional, SurgicalDocument11 pagini8 - Maxillary Expansion in Nongrowing Patients. Conventional, SurgicalMariana SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bhanu Impaction Seminar FinalDocument138 paginiBhanu Impaction Seminar FinalBhanu PraseedhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of Growth in Orthodontics FinalDocument21 paginiAssessment of Growth in Orthodontics FinalSaumya Singh100% (1)

- Bahan Jurnal Neglected Fractures of FemurDocument5 paginiBahan Jurnal Neglected Fractures of Femurgulamg21Încă nu există evaluări

- The Kinetics of Anterior Tooth DisplayDocument3 paginiThe Kinetics of Anterior Tooth DisplayYu Yu Victor Chien100% (1)

- Topic - Rapid Maxillary ExpansionDocument39 paginiTopic - Rapid Maxillary Expansion王鈴鈞Încă nu există evaluări

- Chairside Diagnostic Kit - Dr. PriyaDocument25 paginiChairside Diagnostic Kit - Dr. PriyaDr. Priya PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Molares InclinadosDocument13 paginiMolares Inclinadosmaria jose peña rojas100% (1)

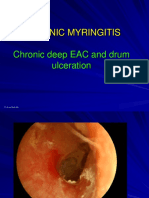

- 3 Chronic MyringitisDocument19 pagini3 Chronic MyringitissyahputriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tarrson Family Endowed Chair in PeriodonticsDocument54 paginiTarrson Family Endowed Chair in PeriodonticsAchyutSinhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BiostatisticsDocument7 paginiBiostatisticsSaquib AzeemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tran 2018Document5 paginiTran 2018Zachary DuongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relationship Between Crown-Root Angulation (Collum Angle) of Maxillary Central Incisors in Class II, Division 2 Malocclusion and Lower Lip LineDocument9 paginiRelationship Between Crown-Root Angulation (Collum Angle) of Maxillary Central Incisors in Class II, Division 2 Malocclusion and Lower Lip LineSri RengalakshmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Bite: A Review of Etiology and Management: Peter Ngan, DMD Henry W. Fields, DDS, MS, MSDDocument8 paginiOpen Bite: A Review of Etiology and Management: Peter Ngan, DMD Henry W. Fields, DDS, MS, MSDAzi Pertiwi HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treatment Plasmablastic LymphomaDocument35 paginiTreatment Plasmablastic Lymphomavladimirkulf2142Încă nu există evaluări

- MSE 10.1016@j.ajodo.2016.10.025Document11 paginiMSE 10.1016@j.ajodo.2016.10.025Neycer Catpo NuncevayÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4224 PDFDocument4 pagini4224 PDFDrDikshita BhowmikÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Articulators in Orthodontics and Orthognatic SurgeryDocument5 paginiThe Role of Articulators in Orthodontics and Orthognatic SurgeryDr Shivam VermaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full Mouth Rehabilitation of A Patient With Ra PDFDocument3 paginiFull Mouth Rehabilitation of A Patient With Ra PDFdehaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Miniscrew Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (Marpe) - ExpandingHorizons To Achieve An Optimum in Transverse Dimension A ReviewDocument15 paginiMiniscrew Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (Marpe) - ExpandingHorizons To Achieve An Optimum in Transverse Dimension A Reviewaa bbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Treatment of Class III Malocclusion With Modified Tandem Traction Bow Appliance and A Brief Literature Review 2247 2452.1000644Document5 paginiEarly Treatment of Class III Malocclusion With Modified Tandem Traction Bow Appliance and A Brief Literature Review 2247 2452.1000644kinayungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sling and Tag Suturing Technique For Coronally Advanced FlapDocument7 paginiSling and Tag Suturing Technique For Coronally Advanced FlapFerdinan Pasaribu0% (1)

- Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, And Endodontology Volume 93 Issue 1 2002 [Doi 10.1067_moe.2002.119519] Norbert Jakse; Vedat Bankaoglu; Gernot Wimmer; Antranik Eskici; -- Primary WounDocument6 paginiOral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, And Endodontology Volume 93 Issue 1 2002 [Doi 10.1067_moe.2002.119519] Norbert Jakse; Vedat Bankaoglu; Gernot Wimmer; Antranik Eskici; -- Primary WounMr-Ton DrgÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6c5e PDFDocument1 pagină6c5e PDFMas TellawyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indice de Placa Silness Loe y Articulo Original 1967 PDFDocument7 paginiIndice de Placa Silness Loe y Articulo Original 1967 PDFJaime OspinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role of A Pedodontist in Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate Rehabilitation - An OverviewDocument25 paginiRole of A Pedodontist in Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate Rehabilitation - An OverviewIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spradley1981 PDFDocument10 paginiSpradley1981 PDFFernando Ruiz BorsiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ribbond: A Reinforced Polyethylene Ribbon: - Boon To PedodontistDocument21 paginiRibbond: A Reinforced Polyethylene Ribbon: - Boon To Pedodontistdr parveen bathlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Endodontics: Success of Maintaining Apical Patency in Teeth With Periapical Lesion: A Randomized Clinical StudyDocument9 paginiEndodontics: Success of Maintaining Apical Patency in Teeth With Periapical Lesion: A Randomized Clinical StudyCaio Balbinot100% (1)

- Hamed Personal S & ArticleDocument12 paginiHamed Personal S & Articleحامد بكريÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tent-Pole in Regeneration TechniqueDocument4 paginiTent-Pole in Regeneration TechniqueangelicapgarciacastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Retention Characteristics of Hawley and Vacuum-FormedDocument8 paginiThe Retention Characteristics of Hawley and Vacuum-FormedYayis LondoñoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abi Nader S, - Plaque Accumulation Beneath Maxillary All-On-4™ Implant-Supported ProsthesesDocument6 paginiAbi Nader S, - Plaque Accumulation Beneath Maxillary All-On-4™ Implant-Supported ProsthesesAnsaquilo AnsaquiloÎncă nu există evaluări

- RPH Clasp Assembly - A Simple Alternative To Traditional DesignsDocument3 paginiRPH Clasp Assembly - A Simple Alternative To Traditional DesignsFaheemuddin Muhammad0% (1)

- Consensus of Prostho On Implants-2017Document148 paginiConsensus of Prostho On Implants-2017Faheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Let S Be Your Guide-PoundDocument8 paginiLet S Be Your Guide-PoundFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modified Pontic Design For Ridge DefectsDocument11 paginiModified Pontic Design For Ridge DefectsFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5trial Visits and DentureDocument12 pagini5trial Visits and DentureFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modular DenturesDocument4 paginiModular DenturesFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Be Happy - WayToGodDocument65 paginiHow To Be Happy - WayToGodFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Denture Complaint PDFDocument10 paginiDenture Complaint PDFFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rehab of Severley Worn Dentition-Using Fixed and RemovableDocument0 paginiRehab of Severley Worn Dentition-Using Fixed and RemovableFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why-When-How - To Increase Ovd PDFDocument6 paginiWhy-When-How - To Increase Ovd PDFFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Dental Academy - Theories of Impression Making in Complete Denture Treatment PDFDocument15 paginiIndian Dental Academy - Theories of Impression Making in Complete Denture Treatment PDFFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 Steps To Overcome Social Anxiety - Chapter 1Document22 pagini10 Steps To Overcome Social Anxiety - Chapter 1kapilnabarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ridge Defects and Pontic DesignDocument14 paginiRidge Defects and Pontic DesignFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- PersonalityDocument77 paginiPersonalityFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saudi Aramco Medical Services Organization: Plan Helper CalendarDocument1 paginăSaudi Aramco Medical Services Organization: Plan Helper CalendarFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curve of Spee in Prostho-Broadrick Flag TechniqueDocument5 paginiCurve of Spee in Prostho-Broadrick Flag TechniqueFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Defining and Diagnosing Burning Mouth Syndrome PDFDocument9 paginiDefining and Diagnosing Burning Mouth Syndrome PDFFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impression Theories in Complete DenturesDocument2 paginiImpression Theories in Complete DenturesFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Facebow Calliper ReviewDocument5 paginiFacebow Calliper ReviewFaheemuddin Muhammad100% (3)

- Treatment of Grossly Resorbed Mandibular Ridge 1Document48 paginiTreatment of Grossly Resorbed Mandibular Ridge 1Faheemuddin Muhammad0% (1)

- Effective Suction-Imporession For Retentive Mand Dentture PDFDocument24 paginiEffective Suction-Imporession For Retentive Mand Dentture PDFFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- PaperDocument4 paginiPaperFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effective Suction-Imporession For Retentive Mand Dentture PDFDocument24 paginiEffective Suction-Imporession For Retentive Mand Dentture PDFFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Review of The Clinical Significance of The Occlusal Plane Variation and Head PostureDocument74 paginiA Review of The Clinical Significance of The Occlusal Plane Variation and Head PostureFaheemuddin MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zemoso - PM AssignmentDocument3 paginiZemoso - PM AssignmentTushar Basakhtre (HBK)Încă nu există evaluări

- 09B Mechanical Properties of CeramicsDocument13 pagini09B Mechanical Properties of CeramicsAhmed AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blessing of The Advent WreathDocument3 paginiBlessing of The Advent WreathLloyd Paul ElauriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adjectives Comparative and Superlative FormDocument5 paginiAdjectives Comparative and Superlative FormOrlando MiguelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Education - Khóa học IELTS 0đ Unit 3 - IELTS FighterDocument19 paginiEducation - Khóa học IELTS 0đ Unit 3 - IELTS FighterAnna TaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music Recognition, Music Listening, and Word.7Document5 paginiMusic Recognition, Music Listening, and Word.7JIMENEZ PRADO NATALIA ANDREAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anesthesia 3Document24 paginiAnesthesia 3PM Basiloy - AloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decision Trees QuestionsDocument2 paginiDecision Trees QuestionsSaeed Rahaman0% (1)

- Biomedical EngineeringDocument5 paginiBiomedical EngineeringFranch Maverick Arellano Lorilla100% (1)

- February 2023 PROGRAM OF THE MPLEDocument8 paginiFebruary 2023 PROGRAM OF THE MPLEDale Iverson LacastreÎncă nu există evaluări

- NACH FormDocument2 paginiNACH FormShreyas WaghmareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ulangan Tengah Semester: Mata Pelajaran Kelas: Bahasa Inggris: X Ak 1 / X Ak 2 Hari/ Tanggal: Waktu: 50 MenitDocument4 paginiUlangan Tengah Semester: Mata Pelajaran Kelas: Bahasa Inggris: X Ak 1 / X Ak 2 Hari/ Tanggal: Waktu: 50 Menitmirah yuliarsianitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adhi Wardana 405120042: Blok PenginderaanDocument51 paginiAdhi Wardana 405120042: Blok PenginderaanErwin DiprajaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accomplishment Report Rle Oct.Document7 paginiAccomplishment Report Rle Oct.krull243Încă nu există evaluări

- Tool 10 Template Working Papers Cover SheetDocument4 paginiTool 10 Template Working Papers Cover Sheet14. Đỗ Kiến Minh 6/5Încă nu există evaluări

- Nepal Health Research CouncilDocument15 paginiNepal Health Research Councilnabin hamalÎncă nu există evaluări

- AIPMT 2009 ExamDocument25 paginiAIPMT 2009 ExamMahesh ChavanÎncă nu există evaluări

- API Filter Press - Test ProcedureDocument8 paginiAPI Filter Press - Test ProcedureLONG LASTÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pelatihan Olahan Pangan Ukm LamselDocument6 paginiPelatihan Olahan Pangan Ukm LamselCalista manda WidyapalastriÎncă nu există evaluări

- HIPULSE U 80kVA 500kVA-Manual - V1.1Document157 paginiHIPULSE U 80kVA 500kVA-Manual - V1.1joseph mendezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 2 ME 326Document10 paginiAssignment 2 ME 326divided.symphonyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Web Script Ems Core 4 Hernandez - Gene Roy - 07!22!2020Document30 paginiWeb Script Ems Core 4 Hernandez - Gene Roy - 07!22!2020gene roy hernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic: Going To and Coming From Place of WorkDocument2 paginiTopic: Going To and Coming From Place of WorkSherry Jane GaspayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hijama Cupping A Review of The EvidenceDocument5 paginiHijama Cupping A Review of The EvidenceDharma Yoga Ayurveda MassageÎncă nu există evaluări

- Service Manual - DM0412SDocument11 paginiService Manual - DM0412SStefan Jovanovic100% (1)

- Lenovo TAB 2 A8-50: Hardware Maintenance ManualDocument69 paginiLenovo TAB 2 A8-50: Hardware Maintenance ManualGeorge KakoutÎncă nu există evaluări

- Io (Jupiter Moon)Document2 paginiIo (Jupiter Moon)FatimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RX Gnatus ManualDocument44 paginiRX Gnatus ManualJuancho VargasÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8582d Soldering Station English User GuideDocument9 pagini8582d Soldering Station English User Guide1valdasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peseshet - The First Female Physician - (International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, Vol. 32, Issue 3) (1990)Document1 paginăPeseshet - The First Female Physician - (International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, Vol. 32, Issue 3) (1990)Kelly DIOGOÎncă nu există evaluări

![Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, And Endodontology Volume 93 Issue 1 2002 [Doi 10.1067_moe.2002.119519] Norbert Jakse; Vedat Bankaoglu; Gernot Wimmer; Antranik Eskici; -- Primary Woun](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/224676744/149x198/8c2fa96a30/1400316861?v=1)