Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

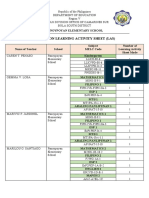

No 4

Încărcat de

Shahnizam SamatDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

No 4

Încărcat de

Shahnizam SamatDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Curriculum Use in the Classroom

M Ben-Peretz and B Eilam, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Glossary

Commonplaces They refer to the main issues and topics treated by curriculum developers in the development process: teacher, learner, subject matter, milieu (Schwab, 1973).

Teachers as Curriculum Users

The following are possible distinct curriculum uses by teachers (Ben-Peretz, 1990). From research conducted in the 1980s on the way in which teachers used curriculum materials, the following modes were found to articulate different uses. Teachers as Users of Teacher-Proof Curriculum In this mode, teachers are expected to use the planned curriculum explicitly as it is prescribed. In order to achieve this goal, the curriculum presents teachers with minute details of the intended use. Teachers as Curriculum Choice Makers In this mode, teachers apply their own principles, criteria, and awareness of concrete circumstances to make decisions about the specific curriculum content, such as part of the textbook, to use in their teaching. Oftentimes, constraints constitute a strong component in this process. Another issue is the pedagogical tension between breadth versus depth in teaching any subject-matter area. Teachers may also be influenced in their choices by their understanding of the nature of students, their abilities, interest, or prior knowledge. Teachers as Curriculum Adaptors Teachers may act as curriculum adaptors who change the curriculum materials in response to the perceived needs of their students, or in line with their own interest and knowledge base. Fullan (1982) mentions the tremendous power teachers have to introduce any changes they see appropriate in the process of curriculum implementation. Teachers adaptation of curriculum, and their attempts to introduce changes in existing texts, raises the problem of adherence to curricular guidelines or to curriculum materials. How far may teachers go in their adaptations without destroying the spirit and meaning of the planned curriculum they implement in their classes? Curriculum analysis may help teachers recognize the special characteristics of curriculum materials. Such insights may aid teachers in their efforts to interpret materials and to plan their lessons on the basis of this interpretation. The term curriculum

Curriculum use may be defined as the ways in which curriculum materials are employed, applied, treated, and even manipulated by several stakeholders in the educational world. Curricular materials mentioned are: syllabi; teacher handbooks or guidelines; textbooks; additional instructional materials, such as worksheets, films, tapes, and so forth; and materials for student assessment, tests, and other kinds of examination modes, such as questionnaires measuring attitudes toward specific subject-matter areas. In this article, stakeholders are conceived of as representatives of three of the four commonplaces that Schwab (1973) suggested as the three main realms of curriculum, namely, learner, teacher, and milieu. The milieu is represented in this article by members of society. The mode of curriculum use by these stakeholders has far-reaching consequences. The article begins with the presentation of each stakeholders mode/s of curriculum use based on relevant literature. The modes of use in each case are analyzed on a continuum from low to intensive engagement with the curriculum. Low engagement refers to little active involvement, either as learners, teachers, or members of society. Intensive engagement means active involvement in decision making concerning the nature of curriculum materials. After presenting the uses of each stakeholder, an integrative, comprehensive model for analyzing curriculum use is presented, accounting for the nature of users and intensity of engagement with curriculum materials. In order to focus explicitly on the separate modes of use of each stakeholder, the interactions and linkages among the three are related throughout the text. Such linkages may have an impact on curriculum use. For instance, there may be a very strong demand by societal agents such as a Ministry of Education that teachers use National Curriculum as it is planned; or teachers use may be shaped by learners nature, for instance, in the case of new immigrants at schools.

348

Curriculum Use in the Classroom

349

envelope has been suggested for describing the special characteristics of the planned curriculum. Inside this envelope, teachers may plan their own mode of use. Teachers as Creators of Curriculum Finally, teachers as creators of curriculum may create their own curriculum materials, based on specific general guidelines or syllabi, or completely independently. Teacherbased curriculum development may be called forth for a number of reasons. Special needs of student groups may require individualized curriculum materials which are not to be found commercially. The faculty of a school may decide to try to react to some societal problems, such as a high incidence of teenage pregnancies, through the local development of a course on family life and family planning. Because of the great sensitivity of such issues, it is necessary to bear in mind the specific beliefs and values of students, parents, and community while constructing such a course. Such school-based curriculum development (SBCD) may cover a whole school curriculum, or be confined to individual subjects or themes. According to Marsh et al. (1990), the term school based curriculum development (SBCD) is used in various ways in the literature but typically as a slogan for devolution of control, for grass-roots decision-making, and as a representation of the polar opposite of centralized education (p. ix). Though there is a tendency nowadays to move toward more centralistic school systems, for instance, through enforcing standards, or the national curriculum in England, the practice of SBCD still seems to be occurring, and sometimes even flourishing. Marsh et al. claim that it is unlikely that schools will retreat to an isolated existence where parents and community have no say in curriculum matters. At the site-level of SBCD, both personal and social processes have a strong impact on teachers use of curriculum. Fullan (1982) points out that beliefs guide and are informed by teaching strategies and activities and Miller and Seller (1985) go on to claim that personal factors affect implementation and use of curriculum materials. Miller and Seller (1985) argue that too often, implementation is centered on things, such as textbooks, teaching aids, and explanatory booklets. However, implementation is not as one-sided as it is often portrayed; rather, it is an interactive process during which the teacher adapts the program to his/her educational context.

developers intentions, Schwab (1973) warns us that these intentions convey the values of the developers only imperfectly and merely suggest ways of constructing teaching activities. Actual classroom experiences of the curriculum might serve to reduce the ambiguity of the stated intentions as well as modify them. Implementation of ideas and activities, which are proposed in the curriculum, turns these into concrete experiences. These experiences may correspond to the perceived intentions of the developers, but they may also serve different ends. It is important to remember that the notion of curriculum potential is dependent on the interaction between teachers and materials. Materials offer starting points, and teachers use their curricular insights, their pedagogical knowledge, and their professional imagination to develop their own curricular ideas on the basis of existing materials. The scope, variety, and richness of the curriculum potential embodied in materials are determined by the wealth of their content and the flexibility or rigidity of their structure. Good curriculum materials have many different potentials for diverse educational situations. In terms of the continuum from low to intensive engagement with the curriculum, here the movement is from being users of teacher-proof curriculum to teachers as curriculum planners.

Learners as Curriculum Users

One of the most critical phases of the curriculum transformation model, suggested by Goodlad et al. (1979), is curriculum as experienced by students. Usually, the experienced curriculum is evaluated through measuring students achievement. The notion of learners experiences is expanded to include the process of actual interaction between students and curriculum materials such as understanding of text or manipulation of tasks. Students may play a role in evaluating curriculum materials. Overall, it is deemed important to give students a voice in curriculum matters. Frequently, classroom context determines to a large extent the role of students as curriculum users. The interaction of students with textbooks cannot be viewed as an entirely passive process. There is an implicit assumption that meaning is determined by the text itself. This approach neglects the reality of interpretation of textbooks by students. Depending on social context and social psychological variables such as ethnicity, gender, social class, personality and psycho-pathogenesis, individual pupils may reach vastly different interpretations or decodings of one and the same text (Kalmus, 2004: 470471). These interpretations by students may be conceived as an important component of classroom curriculum use. One of the modes of students interacting with the curriculum is in the form of a community of discourse.

The Notion of Curriculum Potential

One of the ways in which teachers gain ownership of the curriculum is through their imaginative use of curriculum potential (Ben-Peretz, 1990). Although curriculum materials are often perceived as the expression of their

350

Curriculum Development Evaluation and Research

Interpretive community is one in which constructive discussion, questioning, and criticism are the rule rather than the exception. Students and teachers alike have ownership of knowledge and experience but no one has expertise in all areas. Members of the community share their expertise through reciprocal teaching and collaborative learning activities. In such an environment, students may act as teachers and discussion leaders, thus having an active role in curriculum use. In a constructivist classroom, students are viewed as thinkers with emergent theories about the world and teachers seek the students points of view in order to understand students conceptions for use in teaching. In this sense, students become part of the planners of curriculum use. This active role of students is opposed to their role in traditional classrooms, where students are often viewed as blank slates onto which information is etched by the teacher. Typical constructivist instruction asks learners to play more of the task-management role than in conventional instruction. Self-directed learning represents an independent mode of curriculum use, through assignment, theme, and topics for students to learn by themselves (e.g., problem-based learning, inquiry, projects). Independent and self-regulated learning usually takes place in the frame of the mandated school curricula. This kind of learning may focus on several key self-directed learning processes: defining what should be learned, developing learning goals, identifying a learning plan, successfully implementing it, and self-evaluating the effectiveness of learning. Thus, students almost develop a curriculum according to the Tylerean rationale. Among the salient approaches to involving students in curriculum implementation is, for instance, designbased science curriculum, learning and teaching through inquiry, or project-based classroom learning. Openinquiry instruction is beneficial in engaging students at all levels of achievement in the learning process (Yerrick, 2000). The just the basic mentality and compromising science by watering down the curriculum for lower track students continue to perpetuate a learned helplessness for these students regarding scientific knowledge (Yerrick, 2000: 231). In this case, allowing students to play a highly active role in the curriculum is a prerequisite of successful curriculum implementation. There is an important message in these findings for the development of educative curriculum materials. In order to help students learn in the most productive ways, and be successful curriculum users, curriculum materials need to be designed to support teachers in engaging in particular teachinglearning processes and in addressing particular learning challenges. Teachers have to become aware of the positive impact of giving students an active role in the implementation of curriculum. Homework may be conceived of as an extension of students curriculum use outside the frame of school.

Almost all children at school all over the world are asked to do some kind of homework. In this sense, the curriculum comes home, where it is used, and not only in the classroom. There is generally consistent evidence for a positive influence of homework on achievement, especially in grades 712. The movement here in terms of the continuum from low to intensified engagement with the curriculum is from students reading prescribed texts to students as independent learners in the inquiry mode.

Society as a Curriculum User

Society constitutes an important stakeholder. As stated above, society, the milieu commonplace includes members of society such as diverse societal groups, policymakers, and parents. However, unlike the direct use of curriculum by teachers and students in the classroom, curricula serve to mediate between society and its goals and are used for achieving diverse societal goals and agenda. Such goals are constantly changing in accordance with the various contexts, local or global, as they are perceived in different times. Society and culture affect classroom use of curriculum as far as related to curriculum content and proposed goals. Increased literacy demands and diversity in student populations are only two of several social changes affecting the scope and complexity of curriculum use in classrooms (Sowell, 2000: 110). An example for curriculum fostering societal goals is the response of educators in the USA to the competition in space technology with the Soviet Union. As long ago as the 1940s, Tyler regarded society as one of the sources of curriculum objectives, viewing the curriculum as serving societal needs. Curriculum scholars from the 1960s onward challenge the perception of society as a single entity, and called for a re-conceptualization of curriculum theories, which always carry a privileging dimension that serves some groups and individuals, while simultaneously harming others (Hlebowitsh, 1999: 345). They call for an increased sensitivity to social contexts and issues of race, ethnicity, gender, or social status, moving away from the imposing of control of one societal group over others (Hlebowitsh, 1999).

Social Class as Stakeholder

Curriculum dialog was enriched, becoming also more controversial, by the deepening and widening of perspectives regarding its use in schools and the revelation of the various mechanisms working behind curriculum use. Already, in 1981, in her well-known study, Jean Anyon called attention to school reproduction of unequal class structure (Anyon, 1981). Anyon demonstrated subtle

Curriculum Use in the Classroom

351

differences in the curriculum in use among schools situated in contrasting social-class settings. What counts as knowledge in these schools was found to be different along dimensions of structure and content. Curricula in the working-class schools were only partially used in comparison to elite schools, where high cognitive demands were placed on learners. By situating school knowledge in the particular social setting, Anyon showed how it contributes to contradictory social processes of conservation and transformation. Schools play a central role in both changing and reproducing social and cultural inequalities along generations.

Curriculum as Political Text

School was not perceived anymore as detached from ideologies or politics; rather, the term of ideological hegemony was coined together with the resulting belief that only a critical approach would undermine the reproductive forces and present individuals with alternatives (McLaren, 1989). Curriculum was perceived as a political text, aiming at the perpetuation of domination of the rich and strong over the weak and poor in society. The concept of the hidden curriculum has been used to describe all the implicit and tacit assumptions and ways in which knowledge influences behaviors and thoughts (Jackson, 1968). It is well understood that books, images, and media used in schools perpetuate negative racial and gender-related attitudes. A recent example of a societys use of curriculum to respond to political needs is post-apartheid South Africa (Fataar, 1997). Placement of two million children in schools was viewed as central to rebuilding the country. The curriculum had to be changed from a colonial white curriculum to a post-colonial indigenous one. A policy of quantitative expansion of schooling should not ignore the quality of schools; otherwise, education becomes a factor contributing to social inequality rather than to social reconstruction.

(Bishop, 1990; Smith, 1999). Various countries formed committees and initiatives to deal with employmentrelated key competencies while reevaluating and adapting national educational goals to face these changes (Smith, 1999). In the USA, national economic/educational goals were proposed in response to the skill gap. However, the debate concerning issues dealing with the need for preparing students for higher demands of workplace, and with the ability to transfer school-acquired procedural knowledge to the workplace, or the relations between education and worker productivity, continues. In the past, some researchers suggested no necessary connections between education and workplace productivity (Bishop, 1990) or argued that such relationships between workplace characteristics and cognitive demands of workers were more complex and less direct (Smith, 1999). Kress (2000) suggested that demands of the coming era require education for instability rather than being directed for a certain disposition and cultural reproduction. He claims that present curricula in most Western states were developed to needs of nineteenth-century school, with its desire for a homogeneously conceived citizen for that state (p. 134). He calls for the dissolution of former frames and the emergence of new framings (Kress, 2000).

Parents as Stakeholders

Among the societal stakeholders in the curriculum domain, parents tend to play a central role (Klicka, 1998; OECD, 1997). Parents send their children to school so that they attain the necessary knowledge to function in the societal context and the labor market. The school curriculum and its uses are vehicles for achieving these goals. How much, if any, impact do parents have on the development and use of curriculum? Involvement of parents in curriculum development is usually lacking except in special cases of SBCD. On the other hand, parents involvement in curriculum uses may be rather significant. Parents may play a role in assisting their children in school tasks, such as homework or projects. Usually their involvement reflects the provision of home support to their children in homework performance or learning for exams. Parents may also act as supporters, or obstacles, in the path of curriculum innovation. Parents involvement in the curriculum process, especially in reform movements, requires explaining the new approach of teaching and learning involved in the innovation. The most active and involved role of parents in the curriculum domain is in the context of home schooling (Klicka, 1998). Home schooling means that parents adopt the role of teachers including the planning of curriculum materials. Parents rely on numerous educational curricula and resources that are available to them. Independent

Curriculum as Economic Text

The social dimension of curriculum use, societal utilization of curriculum in the classroom to achieve its own goals, may be best exemplified by literature reports concerning the preparation of students for labor in the current globalization and technological age. Although it is impossible to predict the future, one may recognize some core trends against which societal agendas may be evaluated. It is often indicated that characteristics of work are greatly changing especially concerning the demands for skills and technology, due to the rapid pace of changing economy and technology. Standards of efficiency, productivity, and quality are raised due to global competition

352

Curriculum Development Evaluation and Research

studies were found that, on an average, home-schooled children score above average on standardized achievement tests. This outcome reflects the skillful use of existing curricula adapting them to specific teaching situations. The relationship between parental involvement and educational outcomes exists regardless of students socioeconomic or race/ethnic background and regardless of whether parental practices occur in the middle grades or in high school (Catsambis, 2001). Parents as stakeholders come from different social, religious, ethnic, racial, or economic groups, drawing on different value systems, and relating differently to their children or to schools. It is certain that they all want the best for their children, but cannot agree on what best is, making it difficult to uniformly conceptualize parents involvement in the curriculum domain. A number of research projects looked at the relations between schools and parents in different social groups immigrant parents and low socioeconomic status showed that active involvement of parents in school activities promotes students learning and achievements. School activities may be in the form of classroom volunteers, being an integral part of the decision-making process at school, for instance, in curriculum matters. Parents, as educational partners, no longer feel intimidated by teachers but voice their opinions and suggestions for the school curriculum. The term parent power refers to increased parental activism, expressed in increased numbers of parents participation in various organizations and associations. It reflects parents ability to pressure educational systems

to enact a curriculum that responds to their group needs. A current example is parents involvement in the curricular debate concerning the teaching of evolution versus teaching creation (intelligent design). Present-day governments tend to support and legislate for parents collective voice, expressed in parents representation on policymaking bodies at the various levels and parents associations. An interesting survey has shown that one in three students learn in a school where his/her parents may influence the curriculum (OECD, 1996). Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (1997) argued that three major constructs are center to parents involvement in curricular decisions: (a) teachers beliefs about parents roles in their childrens education, (b) parents sense of efficacy for helping their children succeed in school, and (c) the perception that both child and school want parents to be involved. In the case of society as a curriculum user, the move from low to high intensity of engagement has to be analyzed separately for each of the sub-groups mentioned above.

An Integrative Model for Analyzing Curriculum Use

Based on the analysis of each of the stakeholders interactions with the planned curriculum, a model for viewing the complexities of curriculum use and the transformation of the planned into the enacted curriculum is presented (Figure 1). This model is presented in a visual

Teacher

Low

Planned

Curriculum

High

Low Learners Legend Stakeholder Planned curriculum Curriculumstakeholders interactions Between-stakeholders interactions Highlow intensity of engagement

Figure 1 A model for analyzing curriculum use.

Low Society

Curriculum Use in the Classroom

353

form, because the process of curriculum use is conceived as simultaneously involving three different stakeholders. The model consists of a triangle, each apex representing one of the three stakeholders: teacher, learner, society. The teacher is placed at the top, because teachers are considered as main decision makers in curriculum implementation. A circle within the middle part of the triangle represents the planned curriculum. The three shaded parts of the model are formed by the interaction between the stakeholders and the curriculum, and represent the enacted curriculum. In order to remind readers of interactions among stakeholders themselves that potentially have impact on curriculum use (as mentioned before in the text but are not the focus of this article), two-way directional arrows are marked on the three sides of the triangle. The continuum from low to high intensity of engagement is marked by three arrows going from each stakeholder toward the planned curriculum. The closer a point on this continuum (arrow) is to the curriculum, the higher the intensity of engagement. The novelty of this model presented here relates to two aspects of curriculum use: (1) viewing three different users whereas usually teachers alone are considered, and presenting their use as simultaneously enacted, and (2) conceiving of curriculum use as a continuum reflecting intensity of engagement from low to high intensity. This model has the potential to be used in studies of curriculum implementation and in the process of introducing teachers to the curriculum domain. The distinction between low and high level of intensity of users engagement raises research questions that can be studied in relation to each of the subgroups of society, for instance, in relation to immigrant parents. Such a view of engagement allows curriculum researchers to go beyond the measuring of students achievement as major factors in curriculum use. The continuum from high to low intensity of engagement provides refined insights into the understanding of stakeholders impact on curriculum use and may enhance their possible involvement.

Fullan, M. (1982). The Meaning of Educational Change. New York: Teachers College Press. Goodlad, J. I., Klein, M., and Tye, K. (1979). The domains of curriculum and their study. In Goodlad, J. I., Ammons, M. P., Buchanan, E. A., et al. (eds.) Curriculum Inquiry: The Study of Curriculum Practice, pp 4376. New York: McGraw-Hill. Hlebowitsh, P. (1999). The burdens of the new curricularist. Curriculum Inquiry 29, 343354. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. and Sandler, H. M. (1997). Why do parents become involved in their childrens education? Review of Educational Research 67, 342. Jackson, P. (1968). Life in Classrooms. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Kalmus, V. (2004). What do pupils and textbooks do with each other? Methodological problems of research on socialization through educational media. Journal of Curriculum Studies 36, 469485. Klicka, C. J. (1998). The Right to Home School: A Guide to the Law on Parents Rights in Education, 2nd edn. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press. Kress, G. (2000). A curriculum for the future. Cambridge Journal of Education 30, 133145. Marsh, C., Day, C., Hannay, L., and McCutcheon, G. (1990). Reconceptualizing School Based Curriculum Development. Hampshire, UK: Falmer. McLaren, P. (1989). Life in Schools: An Introduction to Critical Pedagogy in the Foundations of Education. New York: Longman. Miller, J. P. and Seller, W. (1985). Curriculum: Perspectives and Practice. New York: Longman. OECD (Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development) (1996). Education at a Glance. Paris: The Center of Educational Research and Innovation. OECD (Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development) (1997). Parents as Partners in Schooling. Paris: The Center of Educational Research and Innovation. Schwab, J. J. (1973). The practical: Translation into curriculum. School Review 81, 501522. Smith, J. P., III (1999). Tracking the mathematic of automobile production: Are schools failing to prepare students for work? American Educational Research Journal 36, 835878. Sowell, E. J. (2000). Curriculum: An Integrative Introduction, 2nd edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. Yerrick, R. K. (2000). Lower track science students argumentation and open inquiry instruction. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 37, 807838.

Further Reading

Brown, A. and Campione, J. C. (1998). Designing a community of young learners: Theoretical and practical lessons. In Lambert, N. M. and McCombs, B. L. (eds.) How Students Learn: Reforming Schools through Learner-Centered Education, pp 153186. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Carreon, G. P., Drake, C., and Barton, A. C. (2005). The importance of presence: Immigrant parents school engagement experiences. American Educational Research Journal 42, 465498. Connelly, M. F. and Clandinin, D. J. (1988). Teachers as Curriculum Planners: Narratives of Experience. New York: Teachers College Press. Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., and Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research 19872003. Review of Educational Research 76, 162. Dalton, D., Dingess, D., Dingess, C., et al. (1996). The parents as educational partners: Programs at Atenville elementary school. Journal for Education for Students Placed at Risk 1, 233247. Gellert, U. (2005). Parents: Support or obstacle for curriculum innovation. Journal of Curriculum Studies 37, 313328. Grant, C. and Sleeter, C. (1986). After the School Bell Rings. Philadelphia, PA: Falmer.

Bibliography

Anyon, J. (1981). Social class and school knowledge. Curriculum Inquiry 11, 342. Ben-Peretz, M. (1990). The TeacherCurriculum Encounter: Freeing Teachers from the Tyranny of Texts. Albany, NY: State University Press. Bishop, J. H. (1990). The productivity consequences of what is learnt in high school. Journal of Curriculum Studies 22, 101126. Catsambis, S. (2001). Expanding knowledge of parental involvement in childrens secondary education: Connections with high school seniors academic success. Social Psychology of Education 5, 149177. Fataar, A. (1997). Access to schooling in a post-apartheid South Africa: Linking concepts to context. International Review of Education 43, 331348.

354

Curriculum Development Evaluation and Research

Rudduck, J. (1999). Teacher practice and the student voice. In Lang, M., Olson, J., Hansen, H., and Bunder, W. (eds.) Changing Schools/ Changing Practices: Perspectives on Educational and Teacher Professionalism, pp 4154. Louvain: Garant. Tyler, R. (1949). Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Zimmerman, B. J. and Lebeau, R. B. (2000). A commentary on selfdirected learning. In Evensen, D. H. and Hmelo, C. E. (eds.) ProblemBased Learning: A Research Perspective on Learning Interactions, pp 299313. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Harker, R. (1990). Bourdieu education and reproduction. In Harker, R., Mahar, C., and Wilkes, C. (eds.) An Introduction to the Work Pierre Bourdieu: The Practice of Theory, pp 86108. London: Macmillan. Kelly, A. V. (1999). The Curriculum: Theory and Practice, 4th edn. London: Paul Chapman. Ortiz-Franco, L. and Flores, W. V. (2001). Sociocultural considerations and Latino mathematics achievement. In Atweh, B., Forgasz, H., and Nebres, B. (eds.) Socio-Cultural Research on Mathematics Education: An International Perspective, pp 233254. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Jadual Guru Kelas PJK 2021Document1 paginăJadual Guru Kelas PJK 2021Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revision - Final Exam Math 4Document14 paginiRevision - Final Exam Math 4Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Room Facilities: Safe, Air Conditioning, Iron, Work Desk, Ironing Facilities, CarpetedDocument1 paginăRoom Facilities: Safe, Air Conditioning, Iron, Work Desk, Ironing Facilities, CarpetedShahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia BWM 21403 - Matematik Iv Revision of TestDocument2 paginiUniversiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia BWM 21403 - Matematik Iv Revision of TestShahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Customer Relationship ManagementDocument54 paginiCustomer Relationship ManagementBalram92% (26)

- No 2Document6 paginiNo 2Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- No 3Document6 paginiNo 3Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- No 1Document7 paginiNo 1Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- No 3Document6 paginiNo 3Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- No 2Document6 paginiNo 2Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artikel No 5Document5 paginiArtikel No 5Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- No 10Document18 paginiNo 10Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- No 1Document7 paginiNo 1Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- No 8Document6 paginiNo 8Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artikel No 5Document5 paginiArtikel No 5Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- No 9Document7 paginiNo 9Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modularization in Vocational Education and Training: H Ertl and G Hayward, University of Oxford, Oxford, UKDocument8 paginiModularization in Vocational Education and Training: H Ertl and G Hayward, University of Oxford, Oxford, UKShahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- No 1Document7 paginiNo 1Shahnizam SamatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form 5: Learning Area 4Document34 paginiForm 5: Learning Area 4Haffiz IshakÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- First HPTA MeetingDocument20 paginiFirst HPTA MeetingRochelle OlivaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adgas Abu DhabiDocument7 paginiAdgas Abu Dhabikaran patelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 03 - Professional PracticeDocument104 paginiUnit 03 - Professional Practicerifashamid25100% (1)

- Architecture - Hybris Lifecycle FrameworkDocument214 paginiArchitecture - Hybris Lifecycle Frameworkrindang cahyaningÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 1. Introduction To Teaching English To Young LearnersDocument2 paginiUnit 1. Introduction To Teaching English To Young LearnersVesna Stevanovic100% (3)

- Institute of Professional Psychology Bahria University Karachi CampusDocument16 paginiInstitute of Professional Psychology Bahria University Karachi Campusayan khwajaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BPC SyllabusDocument3 paginiBPC SyllabusSivaram KrishnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cambridge Companion To Eighteenth-Century OperaDocument340 paginiThe Cambridge Companion To Eighteenth-Century OperaAldunIdhun100% (3)

- Interview DialogueDocument5 paginiInterview Dialogueapi-323019181Încă nu există evaluări

- Hepp Katz Lazarfeld 4Document5 paginiHepp Katz Lazarfeld 4linhgtran010305Încă nu există evaluări

- Giáo Án Anh 8 Global Success Unit 9Document41 paginiGiáo Án Anh 8 Global Success Unit 9Hà PhươngÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Promise of Open EducationDocument37 paginiThe Promise of Open Educationjeremy_rielÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALOHA Course InformationDocument7 paginiALOHA Course InformationAarajita ParinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metaphor Lesson Plan 4th GradeDocument5 paginiMetaphor Lesson Plan 4th Gradeapi-241345614Încă nu există evaluări

- Iex BeginnerDocument22 paginiIex BeginnerNeringa ArlauskienėÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum Vitae and Letter of ApplicationDocument7 paginiCurriculum Vitae and Letter of ApplicationandragraziellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Action Plan Templete - Goal 1-2Document3 paginiAction Plan Templete - Goal 1-2api-254968708Încă nu există evaluări

- Notes by Pavneet SinghDocument9 paginiNotes by Pavneet Singhdevesh maluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sandy Shores: Sink or FloatDocument5 paginiSandy Shores: Sink or FloatElla Mae PabitonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship Handbook (For Students 2220)Document14 paginiInternship Handbook (For Students 2220)kymiekwokÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prepare 2 Test 1 Semester 4Document3 paginiPrepare 2 Test 1 Semester 4Ira KorolyovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LESSON PLAN Template-Flipped ClassroomDocument2 paginiLESSON PLAN Template-Flipped ClassroomCherie NedrudaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 Industrial Training HandbookDocument26 pagini2 Industrial Training HandbookZaf MeerzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Math LessonDocument5 paginiMath Lessonapi-531960429Încă nu există evaluări

- Ifugao: Culture and ArtsDocument35 paginiIfugao: Culture and ArtsJules Michael FeriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gerund and InfinitiveDocument3 paginiGerund and InfinitivePAULA DANIELA BOTIA ORJUELAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grant ProposalDocument5 paginiGrant Proposalapi-217122719Încă nu există evaluări

- Fuhs - Structure and State DevelopmentDocument52 paginiFuhs - Structure and State DevelopmentMichael Kruse Craig100% (1)

- Questionnaire SpendingDocument4 paginiQuestionnaire SpendingNslaimoa AjhÎncă nu există evaluări

- PANOYPOYAN ES Report On LASDocument4 paginiPANOYPOYAN ES Report On LASEric D. ValleÎncă nu există evaluări