Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

BPR Vs Kaizen

Încărcat de

george19821Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

BPR Vs Kaizen

Încărcat de

george19821Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

BUSINESS PROCESS REENGINEERING METHOD VERSUS

KAIZEN METHOD

Cristiana BOGDNOIU

Faculty oI Financial Accounting Management Craiova

Spiru Haret University, Romania

cristina82bgmail.com

Abstract:

The essence of this paper is the comparison of the Business Process Reengineering methoa (BPR)

ana Kai:en methoa.

The BPR methoa is aefinea by Hammer ana Champy as 'the funaamental reconsiaeration ana

raaical reaesign of organi:ational processes, in oraer to achieve arastic improvement of current

performance in cost, service ana speea`.

At its turn, the Kai:en methoa is an management concept for incremental change. The key elements

of Kai:en are quality, effort, involvement of all employees, willingness to change ana communication.

When BPR is comparea with Kai:en methoa, the BPR is haraer to implement, technology orientea,

enables raaical change. On the other hana, Kai:en methoa is easier to implement, is more people

orientea ana requires long term aiscipline.

Key words: business processe reengineering, Kaizen method, incremental improvement,

technology, standardization.

1. Introduction

Quite oIten it is necessary Ior an organization to revise and re-examine it's

decisions, goals, targets etc., in order to improve the perIormance in many ways and this

activity oI re-engineering is called as Business Process Re-engineering which is also

known as Business Process Re-design or Business Process Improvement.

2. Business Process Reengineering (BPR)

Business Process Reengineering began as a private sector technique to help

organizations Iundamentally rethink how they do their work in order to dramatically

improve customer service, cut operational costs, and become world-class competitors. A

key stimulus Ior reengineering has been the continuing development and deployment oI

sophisticated inIormation systems and networks.

Business Process Reengineering involves changes in structures and in processes

within the business environment. The entire technological, human, and organizational

dimensions may be changed in BPR. InIormation Technology plays a major role in

Business Process Reengineering as it provides oIIice automation, it allows the business to

be conducted in diIIerent locations, provides Ilexibility in manuIacturing, permits quicker

delivery to customers and supports rapid and paperless transactions. In general it allows

an eIIicient and eIIective change in the manner in which work is perIormed.

2.1 What is the Business Process Reengineering

The globalization oI the economy and the liberalization oI the trade markets have

Iormulated new conditions in the market place which are characterized by instability and

intensive competition in the business environment. Competition is continuously

increasing with respect to price, quality and selection, service and promptness oI

delivery.

Removal oI barriers, international cooperation, technological innovations cause

competition to intensiIy. All these changes impose the need Ior organizational

transIormation, where the entire processes, organization climate and organization

structure are changed. Hammer and Champy provide the Iollowing deIinitions:

5HHQJLQHHULQJ is the Iundamental rethinking and radical redesign oI business

processes to achieve dramatic improvements in critical contemporary measures oI

perIormance such as cost, quality, service and speed.

3URFHVV is a structured, measured set oI activities designed to produce a speciIied

output Ior a particular customer or market. It implies a strong emphasis on how work is

done within an organization." (Davenport 1993).

Business processes are characterized by three elements:

WKH LQSXWV, (data such customer inquiries or materials),

WKH SURFHVVLQJ oI the data or materials (which usually go through several stages

and may necessary stops that turns out to be time and money consuming), and

WKH RXWFRPH (the delivery oI the expected result).

The problematic part oI the process is processing. Business process reengineering

mainly intervenes in the processing part, which is reengineered in order to become less

time and money consuming.

The term "Business Process Reengineering" has, over the past couple oI year,

gained Increasing circulation. As a result, many Iind themselves Iaced with the prospect

oI having to learn, plan, implement and successIully conduct a real Business Process

Reengineering endeavor, whatever that might entail within their own business

organization.

2.2. The methodology of BPR

Re-engineering is deIined (Hammer & Champy, 1993: 46) as 'the funaamental

rethinking and raaical redesign oI business processes to achieve aramatic improvements

in critical, contemporary measures oI perIormance, such as cost, quality, service and

speed. This deIinition contains Iour key words.

1. The Iirst key word is funaamental. In doing re-engineering, people must ask the

most Iundamental questions about their organizations and how they operate: 'Why ao we

ao what we ao? Ana why ao we ao it the way we ao?`

2. Secondly, raaical design means getting to the root oI things, not making

superIicial changes or Iiddling with what is already in place, but throwing away the old.

3. The third key word is aramatic. Re-engineering isn`t about making marginal or

incremental improvements, but about achieving perIormance improvements.

4. Finally processes. Most organizations are not process-oriented, they are Iocused

on tasks, on jobs, on people, on structures, but not on processes. A process can be deIined

as a collection oI activities that takes one or more kinds oI input and creates an output

that is oI value to the customer (Hammer & Champy, 1993: 32-35).

This eIIort Ior realizing dramatic improvements by Iundamentally rethinking how

the organization`s work should be done distinguishes re-engineering Irom process

improvement eIIorts that Iocus on Iunctional or incremental improvement (Hammer &

Champy, 1993). ThereIore, Handy (1990) states that the theory oI Discontinuous thinking

is central to the BPR process, in stead oI the continuous (incremental) thinking, which is

largely derived Irom scientiIic thinking. This continuous thinking is the keystone to many

oI the quality management techniques. Although the principles oI BPR and the quality

management techniques diIIer, quality programs and re-engineering share a number oI

common themes (BeckIord, 1998). They both start with the needs oI the process

customer and work backwards Irom there. However, the two programs also diIIer

Iundamentally. Quality programs work within the Iramework oI a company`s existing

processes and seek to enhance them or continuous incremental improvement. Quality

improvements seek steady incremental improvement to process perIormance. Re-

engineering seeks breakthroughs, not by enhancing existing processes, but by discarding

them and replacing them with entirely new ones.

BPR is achieving dramatic perIormance improvements through radical change in

organizational processes, rearchitecting oI business and management processes. It

involves the redrawing oI organizational boundaries, the reconsideration oI jobs, tasks,

and skills. This occurs with the creation and the use oI models. Whether those be physical

models, mathematical, computer or structural models, engineers build and analyze

models to predict the perIormance oI designs or to understand the behavior oI devices.

More speciIically, BPR is deIined as the use oI scientiIic methods, models and tools to

bring about the radical restructuring oI an enterprise that result in signiIicant

improvements in perIormance.

Redesign, retooling and reorchestrating Iorm the key components oI BPR that are

essential Ior an organization to Iocus on the outcome that it needs to achieve.

In resuming, the whole process oI BPR in order to achieve the above mentioned

expected results is based on key steps-principles which include redesign, retool, and

reorchestrate.

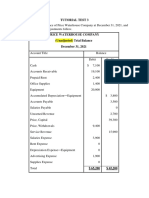

Each step-principle embodies the actions and resources as presented in the table

below.

Table 1. The 3 Rs oI reengineering

REDESIGN

Simplify

Stanaarai:e

Empowering

Employeeship

Groupware

Measurements

RETOOL

Networks

Intranets

Extranets

Workflow

REORCHESTRATE

Synchroni:e

Processes

IT

human resources

Methodology of a BPR project implementation / alternative techniques BPR is

world-wide applicable technique oI business restructuring Iocusing on business

processes, providing vast improvements in a short period oI time. The technique

implements organizational change based on the close coordination oI a methodology Ior

rapid change, employee empowerment and training and support by inIormation

technology. In order to implement BPR to an enterprise the Iollowings key actions need

to take place:

Selection oI the strategic (added-value) processes Ior redesign

SimpliIy new processes - minimize steps - optimize eIIiciency - modeling

Organize a team oI employees Ior each process and assign a role Ior process

coordinator

Organize the workIlow - document transIer and control.

Assign responsibilities and roles Ior each process.

Automate processes using IT (Intranets, Extranets, WorkIlow Management)

Train the process team to eIIiciently manage and operate the new process

Introduce the redesigned process into the business organizational structure

Most reengineering methodologies share common elements, but simple diIIerences

can have a signiIicant impact on the success or Iailure oI a project. AIter a project area

has been identiIied, the methodologies Ior reengineering business processes may be used.

In order Ior a company, aiming to apply BPR, to select the best methodology, sequence

processes and implement the appropriate BPR plan, it has to create eIIective and

actionable visions. ReIerring to 'vision' we mean the complete articulation oI the Iuture

state (the values, the processes, structure, technology, job roles and environment)

For creating an eIIective vision, Iive basic steps are mentioned below.

- the right combination oI individuals come together to Iorm an optimistic and

energized team

- clear objectives exist and the scope Ior the project is well deIined and understood

- the team can stand in the Iuture and look back, rather than stand in the present and

look Iorward

- the vision is rooted in a set oI guiding principles.

2.3. Business Process Re-engineering Examples:

Example1: The entire organization`s business processes or an individual

department`s business processes can be reengineered according to the needs oI an

organization.

For example, a bank may have many activities associated with it like investing,

credit cards, loans, etc., and they may be involved in cross selling(e.g. insurance) with

other preIerred vendors in the market. II the credit card department is not Iunctioning in

an eIIicient manner as the way the bank expected, it might reengineer the 'credit card

business process.

In this situation, bank may think about decreasing the interest rate, oIIering

promotion, redemption, balance transIers etc., to the customers in order to Iacilitate the

perIormance. This would lead to re-engineer or re-design the current bank`s credit card

process. The net eIIect is the improvement in perIormance oI credit card division and

conversely, iI anything goes wrong, major losses are also expected.

Computer system`s inIrastructure, competition, Iinancial strength, expenses

reduction, customer satisIaction, product quality, better management, employees

involvement are some oI the areas that an organization is interested to do business

process reengineering and change the existing processes.

Profect Infrastructure.

An organization may migrate Irom X database to Y database Ior better

perIormance, storage capabilities and reliability.

Competition.

An organization may buy a new and sophisticated application in order to overcome

the competitive pressure.

Financial strength.

Many small and big companies need money to expand their business and in this

situation, they may get loans, or issue shares etc.

Proauct Quality.

A calling card distributor may buy good calling cards Irom the vendors that are

good in quality, time and easy connection.

Example2. A typical problem with processes in vertical organizational structure is

that customers must speak with various staII members Ior diIIerent inquiries. For

example, iI a bank customer enters into the bank determined to apply Ior a loan, apply Ior

an ATM card and open a savings account, most probably must visit three diIIerent desks

in order to be serviced, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Three inquiries three waiting queues

Figure 2. One Stop Service Ior all three inquiries

The diIIerence between the vertical organization (Figure 1) and the cross Iunctional

organization (Iigure 2) lies in the way businesses are organized internally. The vertical

organization is organized based on functional units (e.g. the sales, the accounting

department). In cross-Iunctional organizational units the main organizational unit is the

process. Since "aoing business" is mainly running processes, it would be very logical to

organize companies based on processes. For instance, the ordering process crosses

LOANS

ACCOUNTS

ATM CARDS

ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION

ATM PROCESS

NEW ACCOUNTS PROCESS

LOANS APPLICATION PROCESS

O

R

G

A

N

I

Z

A

T

I

O

N

diIIerent departments: the sales department Ior order taking, the accounting department

Ior credit control and invoicing, the logistics department Ior inventory control and

distribution, and the production department Ior producing the order.

3. Kaizen Method

3.1. The Beginnings of Kaizen

As stated earlier, Kaizen methods Ior work process improvement that include

making the improvements originated in the World War II Job Methods training program.

It was developed by the Training Within Industry (TWI) organization, a component oI

the U.S. War Manpower Commission during World War II. Kaizen methods that suggest

improvements also originated in the work TWI. As suggestion rather than action

improvement programs, Imai points out that, "Less well known is the Iact that the

suggestion system was brought to Japan...by TWI (Training Within Industry) and the

U.S. Air Force" (1986, page 112). Huntzinger (2002) also traces Kaizen back to the

Training Within Industry (TWI) program. TWI was established to maximize industrial

productivity Irom 1940 through 1945. One oI the improvement tools it developed, tested,

and disseminated was labeled "How to Improve War Production Methods." It taught

supervisors the skill oI improving work processes. This program's name was changed to

"How to Improve Job Methods" (War Production Board, 1945, page 191) and is most

oIten reIerred to as Job Methods training. It taught supervisors how to uncover

opportunities Ior improving work processes and implement improvements. It

incorporated a job aid that reminded the person oI the improvement process. This process

began with recording the present method oI operation including details about machine

work, human work, and materials handling - much like a process observations would. It

used challenging questions, to provoke the discovery oI improvement opportunities. It

provided tips Ior eliminating waste - e.g., discards unnecessary steps, combine steps

where possible, simpliIy the operations, and improve sequencing. It incorporated operator

involvement in identiIying waste and developing better ways to do the process. It

instructed people to check out their ideas with others, conclude the best way to make the

improvement, document it, get authorization, and make the improvement. Its

improvements included classic poka yoke solutions like the use oI jigs and guides to

reduce or eliminate errors. TWI emphasized incremental improvements Iocusing on the

processes closest to the person and making improvements that did not require wholesale

redesign oI machines or tools.

3.2. What is Kaizen?

Kaizen is a system oI continuous improvement in quality, technology, processes,

company culture, productivity, saIety and leadership.

Kaizen was created in Japan Iollowing World War II. The word Kaizen means

"continuous improvement". It comes Irom the Japanese words "Kai" meaning school and

"Zen" meaning wisdom.

Kaizen is a system that involves every employee - Irom upper management to the

cleaning crew. Everyone is encouraged to come up with small improvement suggestions

on a regular basis. This is not a once a month or once a year activity. It is continuous.

Japanese companies, such as Toyota and Canon, a total oI 60 to 70 suggestions per

employee per year are written down, shared and implemented.

In most cases these are not ideas Ior major changes. Kaizen is based on making

little changes on a regular basis: always improving productivity, saIety and eIIectiveness

while reducing waste.

Suggestions are not limited to a speciIic area such as production or marketing.

Kaizen is based on making changes anywhere that improvements can be made. Western

philosophy may be summarized as, "iI it ain't broke, don't Iix it." The Kaizen philosophy

is to "do it better, make it better, improve it even iI it isn't broken, because iI we don't, we

can't compete with those who do."

Kaizen in Japan is a system oI improvement that includes both home and business

liIe. Kaizen even includes social activities. It is a concept that is applied in every aspect

oI a person's liIe.

In business Kaizen encompasses many oI the components oI Japanese businesses

that have been seen as a part oI their success. Quality circles, automation, suggestion

systems, just-in-time delivery, Kanban and 5S are all included within the Kaizen system

oI running a business.

Kaizen involves setting standards and then continually improving those standards.

To support the higher standards Kaizen also involves providing the training, materials

and supervision that is needed Ior employees to achieve the higher standards and

maintain their ability to meet those standards on an on-going basis.

Kaizen is Iocused on making small improvements on a continuous basis.

3.3. The Kaizen Philosophy

Improvement has become an integral part oI theories and models oI change such as

structuration theory (Pettigrew, 1990), Ideal types oI change (Van de Ven & Poole,

1995), and cycles oI organizational changes within revolutionary, piecemeal, Iocused,

isolated and incremental changes (Mintzberg & Westley, 1992). Imai (1986) introduced

Kaizen into the western world when he and outlined its core values and principles in

relation to other concepts and the practices involving the improvement process in

organizations (Berger, 1997). Framed as Continuous Improvement (Lillrank & Kano,

1989; Robinson, 1991), the Kaizen philosophy gained recognition and importance when

it was treated as an overarching concept Ior Total Quality Management (TQM) (Imai,

1986; Tanner & Roncarti, 1994; Elbo, 2000), Total Quality Control (TQC) or Company

Wide Quality Control (CWQC) citing practices such as Toyota Production Systems

(TPS) and Just in time (JIT) response systems (Dahlgaard & Dahlgaard-Park, 2006) that

is aimed at satisIying customer expectations regarding quality, cost, delivery and service

(Carpinetti et al., 2003; Juran 1990). With this Iocus on improvement, the Kaizen

philosophy reached notoriety in organizational development and change processes and

has been explained as the 'missing link in western business models (Sheridan, 1997)

and one oI the reasons why western Iirms have not Iully beneIited Irom Japanese

management concepts (Ghondalekar et al. 1995).

Kai:en is a compound word involving two concepts: change (Kai) and to become

good (:en) (Newitt, 1996; Farley, 1999). To engage in Kaizen thereIore is to go beyond

one`s contracted role(s) to continually identiIy and develop new or improved processes to

achieve outcomes that contribute to organizational goals. Kaizen can be understood as

having a spirit oI improvement Iounded on a spirit oI cooperation oI the people,

suggesting the importance oI teams as a Iundamental design in this approach (Tanner &

Roncarti, 1994; Imai, 1997).

Based on the past literature, i summarize the Kaizen methodology as:

1) one that involves all the employees oI the Iirm;

2) improving the methods or processes oI work;

3) improvement are small and incremental in nature and 4) using teams as the

vehicle Ior achieving theses incremental changes.

Kaizen philosophy, however, includes the concept oI Kaizen (Continuous

Improvement) and Kairyo (Process Improvement). Imai (1986) proposes that the Kaizen

philosophy embraces Iour main principles:

Principle1. Kai:en is process orientea. Processes need to be improved beIore

results can be improved. (Imai, 1986, pp. 16-17).

Principle2. Improving ana maintaining stanaaras. Combining innovations with the

ongoing eIIort to maintain and improve standard perIormance levels is the only way to

achieve permanent improvements (Imai, 1986, pp. 6-7).

Kaizen Iocuses on small improvements oI work standards coming Irom ongoing

eIIorts. There can be no improvement iI there are no standards (Imai, 1986, p. 74). The

PDCA cycle (Plan-Do-Check-Act) is used to support the desired behaviors. This cycle oI

continuous improvement has become a common method in Kaizen, it is used to generate

improvement`s habits in employeess.

Principle3. People Orientation. Kaizen should involve everyone in the

organization, Irom top management to workers. One oI the strongest mechanisms

aligning with this third principle is Group-oriented Kaizen (Imai, 1986). Kaizen teams

Iocus primarily on improving work methods, routines and procedures usually identiIied

by management (Imai, 1986).

3.4. The Benefits resulting from Kaizen

Kaizen involves every employee in making change--in most cases small,

incremental changes. It Iocuses on identiIying problems at their source, solving them at

their source, and changing standards to ensure the problem stays solved. It's not unusual

Ior Kaizen to result in 25 to 30 suggestions per employee, per year, and to have over 90

oI those implemented.

For example, Toyota is well-known as one oI the leaders in using Kaizen. In 1999

at one U.S. plant, 7,000 Toyota employees submitted over 75,000 suggestions, oI which

99 were implemented.

These continual small improvements add up to major beneIits. They result in

improved productivity, improved quality, better saIety, Iaster delivery, lower costs, and

greater customer satisIaction. On top oI these beneIits to the company, employees

working in Kaizen-based companies generally Iind work to be easier and more enjoyable-

-resulting in higher employee moral and job satisIaction, and lower turn-over.

With every employee looking Ior ways to make improvements, you can expect

results such as:

Kaizen Reduces Waste in areas such as inventory, waiting times, transportation,

worker motion, employee skills, over production, excess quality and in processes.

Kaizen improves the space utilization, product quality, use oI capital,

communications and production capacity and employee retention.

Kaizen provides immediate results. Instead oI Iocusing on large, capital intensive

improvements, Kaizen Iocuses on creative investments that continually solve large

numbers oI small problems. Large, capital projects and major changes will still be

needed, and Kaizen will also improve the capital projects process, but the real power oI

Kaizen is in the on-going process oI continually making small improvements that

improve processes and reduce waste.

3.5. Varieties of Kaizen Methods

The collection oI Kaizen methods can be organized into the Iollowing categories:

Individual versus teamed,

Day-to-day versus special event, and

Process level versus subprocess level.

Inaiviaual Jersus Teamea

While almost all Kaizen approaches use a teamed approach, there is the method

described as Teian Kaizen or personal Kaizen (Japan Human Relations Association,

1990). Teian Kaizen reIers to individual employees uncovering improvement

opportunities in the course oI their day-to-day activities and making suggestions. It does

not include making the change itselI, but simply the suggestion Ior the change.

Day-to-Day Jersus Special Event

Another example oI a day-to-day Kaizen approach is Quality Circles. Here, a

natural work team (people working together in the same area, operating the same work

process) uses its observations about the work process to identiIy opportunities Ior

improvement. During any day or perhaps at the end oI the week, the team meets and

selects a problem Irom an earlier shiIt to correct. They analyze its sources, generate ideas

Ior how to eliminate it, and make the improvement. This continuous improvement oI the

work process is made in the context oI regular worker meetings.

Special event Kaizens are currently most common. These methods plan ahead and

then execute a process improvement over a period oI days. When they Iocus at the

subprocess level, take place at the work site eliminate waste in a component oI a value

stream. These special events are perIormed in the Gemba - meaning, where the real work

is being done" - e.g., on the shop Iloor or at the point where are service is being

delivered.

Process Level versus Subprocess Level

Most times, Kaizen reIers to improvements made at the subprocess level - meaning,

at the level oI a component work process. For example, imagine the end-to-end

production process associated with manuIacturing shoes. It includes the activities oI

acquiring materials (inputs) Irom suppliers, transIorming them into shoes (output) and

delivering them to customers. One subprocess would be the set oI operations that apply

the sole to the shoe.

The Common Elements. All Kaizen methods that include making change (as

opposed to just suggesting a change) have these common Ieatures. They:

Focus on making improvements by detecting and eliminating waste,

Use a problem solving approach that observes how the work process operates,

uncovers waste, generates ideas Ior how to eliminate waste, and makes

improvements, and

Use measurements to describe the size oI the problem and the eIIects oI the

improvement.

4. Comparison of Business Process Reengineering vs. Kaizen

Table 2 Comparison oI Business Process Reengineering vs. Kaizen

Reengineering Kaizen

Who leads? Usually consultants, top

management, and a cross-

Iunctional Project Team

The people that actually do the work

(with strong guidance in the early years

by top management and a Sensei)

Duration Is a "project" with a deIined

beginning and end

Never ending. Every sub-process should

be kaizened repeatedly Iorever

Type oI

process

Re-engineering works best Ior

processes:

- has cross organizational

boundaries as complex inter-

relationships oI variables

- that involve complex,

integrated technologies

- with medium-length, somewhat

repetitive cycles

Kaizen works best Ior processes:

1. with well-deIined boundaries

2. with most variables in the control oI the

kaizen team

3. that involve low technology - or islands

oI technology

4.with short, highly-repetitive cycles

Scope An entire Value Stream

process

Although kaizen usually starts with a

kaikaku that addresses the entire Value

Stream process - most kaizen events

Iocus on one speciIic sub-process

Degree oI

change

Changes can be incremental or

radical - and usually aIIect an

entire integrated process

Changes can be incremental or radical -

but usually only aIIect a limited sub-

process at a time

Speed Generally implemented in a

Big Bang changeover

Each kaizen event generates

immediately noticeable and measurable

changes

Acceptance High risk oI things reverting

back to the way they were soon

aIter the consultants leave

Since the people that actually do the

work are the ones making the changes -

acceptance is very high

Cost OIten involves expensive

technologies, computers, and

other "systems"

Most "lean" changes are inexpensive or

even Iree

Technology Re-engineering projects are

oIten led by computer

consultants - who tend to "Iix"

most problems with (you

guessed it) computers

Most "lean" methods minimize or even

eliminate reliance on technology - with

a preIerence toward visual methods and

simpliIication

Similarities

x Both address the entire Value Stream oI a process

x Kaizen usually starts out with a kaikaku "big change"

x Both require a qualiIied, competent, and committed Change to have any chance oI

success

5. Conclusion

The essence oI this paper is that the Business Process Reengineering is the redesign

oI business processes and the associated systems and organizational structures to achieve

a dramatic improvement in business perIormance and Kaizen is small improvements and

a change Ior better. It must be accompanied by change oI method.

Business Provess Reengineering is a "project" with a deIined beginning and end,

and Kaizen never ending.

6. References

|1| Berger, A., (1997). Continuous improvement ana Kai:en. Stanaarai:ations ana

organi:ational aesigns, Integrated ManuIacturing System, 8(2), 110-117.

|2| Brunet, A. P. and New, S. (2003), Kai:en in Japan. an empirical stuay. International

Journal oI Operations & Production Management, 23(12), 1426-1446.

|3| Carpinetti, L., Buosi, T., and Gerolamo, M., (2003), Quality Management ana

improvement. A framework ana a business-process reference moael. Business

Process Management Journal, 9(4), 543-554.

|4| Dahlgaard, J. J., and Dahlgaard-Park, S. M., (2006), Lean proauction, six sigma

qualities, TQM ana company culture. The TQM Magazine, 18 (3), 263-281.

|5| Davenport, T. H., and Short, J. E., (1990). The new inaustrial engineering.

Information technology ana business process reaesign. Sloan Management Review,

31(4), 11-27.

|6| Davenport, T. H., (1993). Process Innovation. Reengineering work through

information technology. Boston MA: Harvard Business School Press.

|7| Elbo, R.A.H., (2000). Insiaes Japan Kai:en Power Houses. Business World

Philippines, 13, 1-2.

|8| Farley, C., (1999). Despliegue ae Politicas ael KAIZEN. In: CINTERMEX, ed. XI

Congreso Internacional de Calidad Total, noviembre 1999. Monterrey Nuevo Leon

Mxico: Fundacion Mexicana de la Calidad Total y Centro de Productividad de

Monterrey.

|9| Gondhalekar, S., Babu, S., and Godrej, N., (1995), Towaras using Kai:en process

aynamics. a case stuay, International Journal oI Quality & Reliability Management,

12(9), 192-209.

|10| Imai, M., (1986), Kai:en. The key to Japans Competitive Success, NY: Random

House.

|11| ImaI, M., (1997), GEMBA KAIZEN. A common sense, low cost approach to

management. Kaizen Institute, Ltd.

|12| Juran, J., (1990)., Juran y el Liaera:go para la Caliaaa. Un Manual para Directivos.

Madrid: Editorial Diaz Santos.

|13| Lillrank, P., and Kano, N., (1989). Continuous Improvement. Quality Control

Circles in Japanese inaustries. Ann Arbor MI: University oI Michigan.

|14| Mintzberg, H., and Westley, F., (1992).Cycles of organi:ational change. Strategic

Management Journal 13, 39-59.

|15| Newitt, D. J., (1996). Beyona BPR & TQM - Managing through processes. Is kai:en

enough? In: Proceedings Industrial Engineering, London, U.K: Institution oI

Electric Engineers.

|16| Pettigrew, A. M. (1990). Longituainal Fiela Research. Theory ana Practice.

Organization Science, 1(3), 267-292.

|17| Robinson, A., (1991), Continuous Improvement in Operations. Cambridge, MA:

Productivity Press.

|18| Sheridan, J., (1997). Kai:en Blit:. Industry Week, 246(16), 19-27.

|19| Tanner, C., and Roncarti, R., (1994), Kai:en leaas to breakthroughs in

responsiveness ana the Shingo Pri:e at Critikon, National Productivity Review.

13(4), 517-531.

|20| Van de Ven, A. H., and Poole, M. S. (1995), Explaining Developments change in

organi:ations. Academy oI Management Review, 20(3), 510-540.

|21| Huntzinger, J. (2002), The roots of Lean. Training Within Inaustry. The origin of

Kai:en, Association Ior ManuIacturing Excellence, 18, No. 2. pg. 9 - 22. Available

on line at: http://www.tdo.org/twi/RootsoILean.pdI, viewed February 10, 2005.

|22| War Production Board, Bureau oI Training, Training Within Industry Service,

September 1945, The Training Within Industry Report: 1940-1945, (Washington

D.C.: U.S. Government Printing OIIice).

|23| Hammer, M., Champy, J. (1993). Reengineering the Corporation. A Manifesto for

Business Revolution, New York: HarperCollins,

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Analyzing Financial Performance with Profit & Loss and Balance SheetsDocument27 paginiAnalyzing Financial Performance with Profit & Loss and Balance SheetssheeluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engineer - Trainee and Your Personal Level Will Be 3.: Mysore, India. JulyDocument11 paginiEngineer - Trainee and Your Personal Level Will Be 3.: Mysore, India. Julyദീപക് വർമ്മ50% (4)

- Business Organization and Management - IntroductionDocument17 paginiBusiness Organization and Management - Introductiondynamo vj75% (4)

- PRTC-FINAL PB - Answer Key 10.21 PDFDocument38 paginiPRTC-FINAL PB - Answer Key 10.21 PDFLuna VÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spencer Trading BooksDocument2 paginiSpencer Trading BookscherrynestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Retirement Pay Law in The PhilippinesDocument2 paginiRetirement Pay Law in The PhilippinesBonito BulanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project ManagementDocument13 paginiProject Managementgeorge19821Încă nu există evaluări

- Informative advertising is used heavily when introducing a new product categoryDocument3 paginiInformative advertising is used heavily when introducing a new product categoryMalik Mohamed100% (2)

- Salo Digital Marketing Framework 15022017Document9 paginiSalo Digital Marketing Framework 15022017Anish NairÎncă nu există evaluări

- BPR Business Process Re EngineeringDocument49 paginiBPR Business Process Re EngineeringIshan Kansal100% (1)

- Course Outline Performance Mnagement and AppraisalDocument4 paginiCourse Outline Performance Mnagement and AppraisalFazi Rajput100% (2)

- Lecture 1 - Presentation On BPRDocument31 paginiLecture 1 - Presentation On BPRRahul VashishtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faculty of Management: Barkatullah University, BhopalDocument50 paginiFaculty of Management: Barkatullah University, BhopalA vyasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Om Assignment Edited To PrintDocument7 paginiOm Assignment Edited To PrintMaty KafichoÎncă nu există evaluări

- YARDSTICK INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE - Docx NATI HMRDocument4 paginiYARDSTICK INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE - Docx NATI HMRRekik Solomon100% (1)

- Quantitative Analysis for Decision Making AssignmentDocument8 paginiQuantitative Analysis for Decision Making Assignmentabebe amare100% (2)

- CHAPTER 5 - Quality ManagementDocument21 paginiCHAPTER 5 - Quality ManagementJohn TuahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management AccountingDocument8 paginiManagement AccountingTeresa TanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 Over ViewDocument25 paginiChapter 1 Over ViewAgatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article Review Group AssignmentDocument7 paginiArticle Review Group AssignmentFiseha100% (1)

- Gezahegn Degefa MBA 7188 14ADocument4 paginiGezahegn Degefa MBA 7188 14AGezahegn DegefaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Distinguish Between Production Management and Operation Management. What Is Production Management?Document13 paginiDistinguish Between Production Management and Operation Management. What Is Production Management?Desu mekonnenÎncă nu există evaluări

- A-01 Article ReviewDocument1 paginăA-01 Article ReviewtatekÎncă nu există evaluări

- INTRODUCTION TO OPERATIONS RESEARCH AND LINEAR PROGRAMMINGDocument124 paginiINTRODUCTION TO OPERATIONS RESEARCH AND LINEAR PROGRAMMINGHayder NuredinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Masters of Business Administration: Yardistic International CollegeDocument23 paginiMasters of Business Administration: Yardistic International CollegeGETNET TESEMAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quantitative Analysis for Management Decisions OptimizationDocument50 paginiQuantitative Analysis for Management Decisions OptimizationTsehayou SieleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- BA 5019 SHRM 2 Marks Q & ADocument22 paginiBA 5019 SHRM 2 Marks Q & AMathewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managment Assignment 1Document5 paginiManagment Assignment 1Fasika AbebeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Training and Development Final Question BankDocument2 paginiTraining and Development Final Question Bankshweta dhadaveÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA Organizational Culture Impacts Employee PerformanceDocument5 paginiMBA Organizational Culture Impacts Employee Performancehaile100% (1)

- Strategic Management Concepts and TechniquesDocument2 paginiStrategic Management Concepts and TechniquesViraj BhedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture Notes For Unit 2 PlanningDocument26 paginiLecture Notes For Unit 2 Planningrkar130475% (4)

- New Global Vision Collage 22Document28 paginiNew Global Vision Collage 22Man TKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wolkite University College of Business and Economics Department of ManagementDocument40 paginiWolkite University College of Business and Economics Department of Managementkassahun mesele100% (1)

- Human Resource Management: Short Answer Questions / 2 Mark Question With AnswersDocument3 paginiHuman Resource Management: Short Answer Questions / 2 Mark Question With AnswersANSHID PÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Resource Management Answer Sheet 1Document17 paginiHuman Resource Management Answer Sheet 1Thandapani Palani0% (1)

- HRM Assignment 2Document5 paginiHRM Assignment 2raghbendrashah0% (1)

- The Role of AIS Success On Accounting Information Quality: Azmi Fitriati, Naelati Tubastuvi, Subuh AnggoroDocument9 paginiThe Role of AIS Success On Accounting Information Quality: Azmi Fitriati, Naelati Tubastuvi, Subuh AnggoroThe Ijbmt100% (1)

- Maryland International College Organizational Behavior Final ExamDocument3 paginiMaryland International College Organizational Behavior Final ExamAyalew Lake50% (2)

- The Effect of Working Capital Management On The Manufacturing Firms' ProfitabilityDocument20 paginiThe Effect of Working Capital Management On The Manufacturing Firms' ProfitabilityAbdii DhufeeraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 QuizDocument5 paginiChapter 1 QuizOWEN TOLINÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management Theories & PracticeDocument50 paginiManagement Theories & Practicelemlem sisayÎncă nu există evaluări

- OM Ind. Assignment AnswerDocument5 paginiOM Ind. Assignment AnswerGlobal internet100% (2)

- Ob Assignment 1 by Daniel AwokeDocument9 paginiOb Assignment 1 by Daniel AwokeDani Azmi AwokeÎncă nu există evaluări

- HRD Strategies For Long Term Planning & Growth: Unit-9Document28 paginiHRD Strategies For Long Term Planning & Growth: Unit-9rdeepak99Încă nu există evaluări

- Quantitative analysis mathematical modelsDocument12 paginiQuantitative analysis mathematical modelsDejen Tagelew100% (1)

- 1 CVP RelationshipDocument22 pagini1 CVP RelationshipmedrekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Resource Managment-IntroductionDocument89 paginiHuman Resource Managment-Introductionmomra100% (1)

- Chapter 2Document20 paginiChapter 2setegnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jimma University College of Business and Economics Department of Management MA of Logistics and Supply Chain ManagementDocument4 paginiJimma University College of Business and Economics Department of Management MA of Logistics and Supply Chain ManagementGada Nagari100% (2)

- Jimma University Continuing and Distance Education Operations Management AssignmentDocument10 paginiJimma University Continuing and Distance Education Operations Management AssignmentYohannes SharewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management Information System Assignment On Functional Areas at Different Levels Related To FinanceDocument12 paginiManagement Information System Assignment On Functional Areas at Different Levels Related To FinanceAshad CoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 3 PlanningDocument29 paginiChapter 3 PlanningDagm alemayehuÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHAPTER 1 - A Model For Processing Accounting InformationDocument27 paginiCHAPTER 1 - A Model For Processing Accounting InformationSISCA DKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Outline MGT Theory Word FileDocument5 paginiCourse Outline MGT Theory Word FileSisay Deresa100% (1)

- IHRM Question BankDocument5 paginiIHRM Question Bankruchi agrawalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self Assessment Questions: Chapter-1 ManagementDocument45 paginiSelf Assessment Questions: Chapter-1 ManagementUmashankar GautamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multiple Choice and Short Answer Research QuestionsDocument3 paginiMultiple Choice and Short Answer Research QuestionsRadha Mahat0% (1)

- Operational ReDocument177 paginiOperational Resami damtew0% (1)

- Ethics, Justice, and Fair TreatmentDocument13 paginiEthics, Justice, and Fair TreatmentSarbu NishaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter - 1 - Introduction To Strategic Management AccountingDocument11 paginiChapter - 1 - Introduction To Strategic Management AccountingNusrat Islam100% (1)

- Paper Review by Daniel AwokeDocument11 paginiPaper Review by Daniel AwokeDani Azmi AwokeÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBA Article Review StrategiesDocument6 paginiMBA Article Review StrategiesEbisa Adamu100% (1)

- Sintayehu Final Thesis PDFDocument113 paginiSintayehu Final Thesis PDFsintayehuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Minyichel BayeDocument86 paginiMinyichel BayeMilkias MenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management Control SystemDocument5 paginiManagement Control SystemAnil KoliÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRO Procurement Solutions A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionDe la EverandMRO Procurement Solutions A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Process Re Engineering Vs KaizenDocument12 paginiBusiness Process Re Engineering Vs KaizenReader50% (2)

- Business Process ReengineeringDocument17 paginiBusiness Process Reengineeringmahmoud.saad.refaieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Developing Lean Leaders Chapter 1Document45 paginiDeveloping Lean Leaders Chapter 1george19821Încă nu există evaluări

- BPM Sharepoint User StoriesDocument20 paginiBPM Sharepoint User Storiesgeorge19821Încă nu există evaluări

- BPM Sharepoint User StoriesDocument20 paginiBPM Sharepoint User Storiesgeorge19821Încă nu există evaluări

- Top 10 Tips For BPM ProjectsDocument1 paginăTop 10 Tips For BPM Projectsgeorge19821Încă nu există evaluări

- E Book Kill The Things That Kill ProductivityDocument24 paginiE Book Kill The Things That Kill Productivitygeorge19821Încă nu există evaluări

- TopTV - Bank Details - and - Payment - MethodsDocument1 paginăTopTV - Bank Details - and - Payment - Methodsgeorge19821Încă nu există evaluări

- Flow Chart Mb1Document3 paginiFlow Chart Mb1george19821Încă nu există evaluări

- Time Study & Line Balancing - True VersionDocument7 paginiTime Study & Line Balancing - True Versiongeorge19821Încă nu există evaluări

- Calculating Productivity 102Document7 paginiCalculating Productivity 102george19821Încă nu există evaluări

- Job Tasks ForDocument5 paginiJob Tasks Forgeorge19821Încă nu există evaluări

- PWC Adjusted Trial BalanceDocument2 paginiPWC Adjusted Trial BalanceHải NhưÎncă nu există evaluări

- REVIEWER UFRS (Finals)Document5 paginiREVIEWER UFRS (Finals)cynthia karylle natividadÎncă nu există evaluări

- FAM FormulaDocument19 paginiFAM Formulasarthak mendirattaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 606 Assignment Naresh Quiz 3Document3 pagini606 Assignment Naresh Quiz 3Naresh RaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Copia Zuleyka Gabriela Gonzalez Sanchez - ESB III Quarter Exam Review VocabularyDocument4 paginiCopia Zuleyka Gabriela Gonzalez Sanchez - ESB III Quarter Exam Review Vocabularyzulegaby1409Încă nu există evaluări

- 18MEC207T - Unit 5 - Rev - W13Document52 pagini18MEC207T - Unit 5 - Rev - W13Asvath GuruÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Limitations of Mutual FundsDocument1 paginăThe Limitations of Mutual FundsSaurabh BansalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eap Counselling: Outcomes, Impact & Return On Investment.: Paul J Flanagan & Jeffrey OtsDocument11 paginiEap Counselling: Outcomes, Impact & Return On Investment.: Paul J Flanagan & Jeffrey OtsPavan KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leave Policy in IndiaDocument2 paginiLeave Policy in Indiaup mathuraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abdullah Al MamunDocument2 paginiAbdullah Al MamunMamunBgcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 1.1Document2 paginiAssignment 1.1Heina LyllanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2011 Aring Sup1 Acute CFA Auml Cedil Ccedil Ordm Sect Aring Ccedil Auml Sup1 BrvbarDocument17 pagini2011 Aring Sup1 Acute CFA Auml Cedil Ccedil Ordm Sect Aring Ccedil Auml Sup1 BrvbarBethuel KamauÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian FMCG Industry, September 2012Document3 paginiIndian FMCG Industry, September 2012Vinoth PalaniappanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maithili AmbavaneDocument62 paginiMaithili Ambavanerushikesh2096Încă nu există evaluări

- Diff Coke and PepsiDocument1 paginăDiff Coke and PepsiAnge DizonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transforming HR with Technology ExpertiseDocument2 paginiTransforming HR with Technology ExpertiseAdventurous FreakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multinational Cost of Capital and Capital StructureDocument11 paginiMultinational Cost of Capital and Capital StructureMon LuffyÎncă nu există evaluări

- AUC CHECK REFERENCE FORM - OriginalDocument2 paginiAUC CHECK REFERENCE FORM - OriginalteshomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- THM CH 3Document15 paginiTHM CH 3Adnan HabibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coffee Shop ThesisDocument6 paginiCoffee Shop Thesiskimberlywilliamslittlerock100% (2)

- Project Scope Management - V5.3Document62 paginiProject Scope Management - V5.3atularvin231849168Încă nu există evaluări

- HR Manpower DemandDocument18 paginiHR Manpower DemandMd. Faisal BariÎncă nu există evaluări