Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Location

Încărcat de

Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Location

Încărcat de

Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Location: U.S.

Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay Facts of the Case In 2002 Lakhdar Boumediene and five other Algerian natives were seized by Bosnian police when U.S. intelligence officers suspected their involvement in a plot to attack the U.S. embassy there. The U.S. government classified the men as enemy combatants in the war on terror and detained them at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, which is located on land that the U.S. leases from Cuba. Boumediene filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus, alleging violations of the Constitution's Due Process Clause, various statutes and treaties, the common law, and international law. The District Court judge granted the government's motion to have all of the claims dismissed on the ground that Boumediene, as an alien detained at an overseas military base, had no right to a habeas petition. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit affirmed the dismissal but the Supreme Court reversed in Rasul v. Bush, which held that the habeas statute extends to non-citizen detainees at Guantanamo. In 2006, Congress passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006 (MCA). The Act eliminates federal courts' jurisdiction to hear habeas applications from detainees who have been designated (according to procedures established in the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005) as enemy combatants. When the case was appealed to the D.C. Circuit for the second time, the detainees argued that the MCA did not apply to their petitions, and that if it did, it was unconstitutional under the Suspension Clause. The Suspension Clause reads: "The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it." The D.C. Circuit ruled in favor of the government on both points. It cited language in the MCA applying the law to "all cases, without exception" that pertain to aspects of detention. One of the purposes of the MCA, according to the Circuit Court, was to overrule the Supreme Court's opinion in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, which had allowed petitions like Boumediene's to go forward. The D.C. Circuit held that the Suspension Clause only protects the writ of habeas corpus as it existed in 1789, and that the writ would not have been understood in 1789 to apply to an overseas military base leased from a foreign government. Constitutional rights do not apply to aliens outside of the United States, the court held, and the leased military base in Cuba does not qualify as inside the geographic borders of the U.S. In a rare reversal, the Supreme Court granted certiorari after initially denying review three months earlier. Read the Briefs for this Case Question 1. Should the Military Commissions Act of 2006 be interpreted to strip federal courts of jurisdiction over habeas petitions filed by foreign citizens detained at the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba? 2. If so, is the Military Commissions Act of 2006 a violation of the Suspension Clause of the Constitution? 3. Are the detainees at Guantanamo Bay entitled to the protection of the Fifth Amendment right not to be deprived of liberty without due process of law and of the Geneva Conventions? 4. Can the detainees challenge the adequacy of judicial review provisions of the MCA before they have sought to invoke that review?

Conclusion Decision: 5 votes for Boumediene, 4 vote(s) against Legal provision: Article 1, Section 9, Paragraph 2: Suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus A five-justice majority answered yes to each of these questions. The opinion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, stated that if the MCA is considered valid its legislative history requires that the detainees' cases be dismissed. However, the Court went on to state that because the procedures laid out in the Detainee Treatment Act are not adequate substitutes for the habeas writ, the MCA operates as an unconstitutional suspension of that writ. The detainees were not barred from seeking habeas or invoking the Suspension Clause merely because they had been designated as enemy combatants or held at Guantanamo Bay. The Court reversed the D.C. Circuit's ruling and found in favor of the detainees. Justice David H. Souter concurred in the judgment. Chief Justice John G. Roberts and Justice Antonin Scalia filed separate dissenting opinions.

Summary of Boumediene v. Bush Facts: In 2002, Lakhdar Boumediene and five other Algerian natives were apprehended by Bosnian police based upon the suspicions of U.S. intelligence officers that they were involved in the bombings of a U.S. embassy there. The U.S. was given custody of the men, who were then immediately classified as enemy combatants and detained at the naval base at Guantanamo Bay. Boumediene filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus arguing that the U.S. government violated his Due Process Clause rights. The U.S. District Court dismissed Boumedienes claims on the grounds that he was not a U.S. citizen, and he was detained at an extra-territorial base, thus not entitling him to the same constitutional protections afforded to someone on U.S. soil. The U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed the ruling, but the U.S.S.C. reversed the ruling in Rasul v. Bush and indicated that foreign nationals, even if they are enemy combatants, have at least the right to challenge their enemy combatant status in court. In kind, Congress passed the Military Commissions Act which stripped federal courts of the authority to hear habeas corpus cases from detainees who have been classified as enemy combatants as a means to apparently circumvent the Supreme Court ruling. The detainees applied to the D.C. Circuit Court for a second time, arguing that Congress could not in essence retroactively change the rules of the game, and argued that even if it could, the Suspension Clause which states that, The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it, prevented the Congress from infringing on their rights because there was rebellion or invasion. Since the MCA explicitly stated that it applied to all cases, with no exceptions, the Circuit Court affirmed the governments right to legislate in such a way. The Court ruled that the Suspension Clause was more of a historical relic that only really applied to the circumstances surrounding the political and national security climate in 1789; at that time, it was believed the intent of the amendment was not to protect foreign nationals but citizens. While it initially declined to hear the case, the U.S. Supreme Court eventually decided to hear arguments regarding Boumedienes claims in order to answer the question regarding foreign nationals and the right to due process in the context of detainment in extra-territorial bases. Issue: Several legal questions were presented. They included the following: Should courts interpret the MCA of 2006 to mean that they no longer have any jurisdiction over habeas corpus petitions filed by foreign nationals detained at extra-territorial bases, in this case Guantanamo Bay? If the answer to the first question is in the affirmative, is the MCA of 2006 in violation of the Constitutions Suspension Clause? Are Guantanamo Bay detainees entitled to Fifth Amendment protections without due process of the law and consideration of the Geneva Conventions? Do detainees have to invoke judicial review provision first or can they challenge them on other merits before invoking an actual review? Holding: The Supreme Court ruled affirmatively for all of the questions. Majority Opinion Reasoning: The Court reasoned that prisoners, even enemy combatants, have a right to habeas corpus. The Court reasoned that while Guantanamo Bay is a base located in Cuba, it is still territorially under the control of the United States government; therefore, the Constitution and all of its protections still apply, for it is essentially American soil. Dissenting Opinion: Chief Justice Roberts and Associate Justice Scalia both dissented, simply asserting that foreign nationals, whether named enemy combatants or given another moniker, have never been afforded the right to habeas corpus as a matter of historical record, and thus there was no reason why it should be believed that in 2006 the contextual situation had changed.

Conclusion: This case was significant because it enshrined the precedent that even enemy combatants have habeas corpus rights and that they cannot indefinitely be denied due process under the law simply because they are not citizens. It should be noted however, that the federal government nevertheless maintains a considerable amount of latitude regarding practices concerning enemy detainment in extra-territorial settings, and practices such as rendition further complicate the issue.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- DotesDocument3 paginiDotesHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homestead Patent and Free PatentDocument2 paginiHomestead Patent and Free PatentHiezll Wynn R. Rivera67% (3)

- Labor Er-Ee - LaridaDocument14 paginiLabor Er-Ee - LaridaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

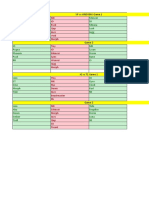

- Parties and Case No. Controversy or Issue Does NLRC Have Jurisdiction? Reason What Happened To The CaseDocument4 paginiParties and Case No. Controversy or Issue Does NLRC Have Jurisdiction? Reason What Happened To The CaseHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labor Er-Ee - LaridaDocument14 paginiLabor Er-Ee - LaridaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- A DadadaDocument1 paginăA DadadaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 7Document5 paginiModule 7Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- EvidenceDocument5 paginiEvidenceHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 321Document1 pagină321Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pecson V MediavilloDocument4 paginiPecson V MediavilloHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angeles City Vs Angeles DigestDocument1 paginăAngeles City Vs Angeles DigestNormzWabanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polytechnic University of The Philippines College of Accountancy and Finance Sta. Mesa, ManilaDocument2 paginiPolytechnic University of The Philippines College of Accountancy and Finance Sta. Mesa, ManilaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Documents - MX People Vs YatcoDocument3 paginiDocuments - MX People Vs YatcoHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Affidavit of Vehicular Accident 2.0Document2 paginiAffidavit of Vehicular Accident 2.0Dee ObriqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- AMDocument1 paginăAMHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Westwind Vs UcpbDocument5 paginiWestwind Vs UcpbHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aaaaa AaaaaaaaaaaaaaaDocument1 paginăAaaaa AaaaaaaaaaaaaaaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1Document2 pagini1Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sanmigcorp Vs NLRCDocument2 paginiSanmigcorp Vs NLRCHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic of The PhilippinesDocument5 paginiRepublic of The PhilippinesHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labor Law 2Document41 paginiLabor Law 2Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Westwind Vs UcpbDocument5 paginiWestwind Vs UcpbHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- BP 129Document7 paginiBP 129Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decision: Riley v. CaliforniaDocument38 paginiDecision: Riley v. CaliforniacraignewmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Strict Nature Reserve" Is An Area Possessing Some Outstanding EcosystemDocument1 pagină"Strict Nature Reserve" Is An Area Possessing Some Outstanding EcosystemHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Certificate of Attendance: AdministrationDocument1 paginăCertificate of Attendance: AdministrationHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- ElccccsDocument4 paginiElccccsHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- RIVERA, Hiezll Wynn R. Common Carrier Defenses Limitation of Liability (2001)Document1 paginăRIVERA, Hiezll Wynn R. Common Carrier Defenses Limitation of Liability (2001)Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. JonesDocument34 paginiUnited States v. JonesDoug MataconisÎncă nu există evaluări

- SMC Vs NLRCDocument1 paginăSMC Vs NLRCHiezll Wynn R. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Complaint Affidavit For LibelDocument4 paginiComplaint Affidavit For LibelLex Dagdag0% (1)

- 290161-2019-Reiterating DILG MC No. 2016-146 On The20220628-11-1civh47Document2 pagini290161-2019-Reiterating DILG MC No. 2016-146 On The20220628-11-1civh47WayneNoveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strengths and Weaknesses of Utilitarianism: Rationality and Practicality Problem With MotiveDocument2 paginiStrengths and Weaknesses of Utilitarianism: Rationality and Practicality Problem With MotivePankaj KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clarifications On The Availment of Monetization of Leave CreditsDocument2 paginiClarifications On The Availment of Monetization of Leave CreditsSusie Garrido100% (14)

- Theories of CSRDocument2 paginiTheories of CSRSiya Ritesh SwamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Air Transpo DigestsDocument6 paginiAir Transpo DigestsMis Dee100% (1)

- Re - Estate Settlement ProceduresDocument7 paginiRe - Estate Settlement ProceduresRonadale Zapata-AcostaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Customer Value Driven Marketing Strategy Developing An Integrated Marketing MixDocument10 paginiCustomer Value Driven Marketing Strategy Developing An Integrated Marketing Mixpranita mundraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deed of AssignmentDocument2 paginiDeed of AssignmentJanz CJÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2ND Wave Case 11 Cir VS GJMDocument2 pagini2ND Wave Case 11 Cir VS GJMChristian Delos ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- TriflesDocument4 paginiTriflesHaryani Mohamad100% (2)

- Directive Principles of State Policy-ADocument11 paginiDirective Principles of State Policy-APratyush Chauhan50% (2)

- Indian Constitution SummaryDocument14 paginiIndian Constitution SummarysudhirsriramojuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foundations of Catholic Morality/ Moral Issues: Ms. PittelDocument2 paginiFoundations of Catholic Morality/ Moral Issues: Ms. Pittelapi-261908516Încă nu există evaluări

- The New FIFA Regulations On Players' AgentsDocument28 paginiThe New FIFA Regulations On Players' AgentsZé DuarteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Merkos L'InyoneI Chinuch, Inc. v. Otsar Sifrei Lubavitch, Inc., 312 F.3d 94, 2d Cir. (2002)Document6 paginiMerkos L'InyoneI Chinuch, Inc. v. Otsar Sifrei Lubavitch, Inc., 312 F.3d 94, 2d Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- CIR v. Burroughs (Digest)Document2 paginiCIR v. Burroughs (Digest)autumn moon100% (1)

- Tax VitugDocument6 paginiTax VitugTrem GallenteÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Jersey V T L oDocument1 paginăNew Jersey V T L oapi-257598923Încă nu există evaluări

- Bail Application PakistanDocument2 paginiBail Application PakistanRahul BishnoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No O. L-38434Document4 paginiG.R. No O. L-38434Charley Labicani BurigsayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Whether Corruption Can Be EradicatedDocument3 paginiWhether Corruption Can Be EradicatedRakesh SrivastavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- J-R-M-, AXXX XXX 954 (BIA June 16, 2017)Document11 paginiJ-R-M-, AXXX XXX 954 (BIA June 16, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crim Pro Digests Nuez UsanaDocument11 paginiCrim Pro Digests Nuez UsanaHarvey Leo Romano100% (2)

- Duties of A Lawyer (F) To (G)Document9 paginiDuties of A Lawyer (F) To (G)Maria Recheille Banac KinazoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Proby Contract With Added ProvisionDocument5 paginiSample Proby Contract With Added ProvisionAndrew Michael TiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- How and Associates, Inc. V BossDocument2 paginiHow and Associates, Inc. V BossTrxc MagsinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advertising and Public Relations Assignment 2Document4 paginiAdvertising and Public Relations Assignment 2Aimen Ashar100% (1)

- Upper-Intermediate - Paying Child Support: Visit The - C 2007 Praxis Language LTDDocument7 paginiUpper-Intermediate - Paying Child Support: Visit The - C 2007 Praxis Language LTDhudixÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Notice of Unavailability of Counsel For CaliforniaDocument3 paginiSample Notice of Unavailability of Counsel For CaliforniaStan Burman100% (1)