Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Fifty-Six Cents - ARCADE - Dialogue On Design

Încărcat de

Leo BloomTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Fifty-Six Cents - ARCADE - Dialogue On Design

Încărcat de

Leo BloomDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

31.

4 CURRENT ISSUE

ISSUES BLOG ARCHIVE EVENTS NEWSLETTER

ABOUT ADVERTISE PARTNER SPONSOR

ARCADE's mission is to incite dialogue about design and the built environment.

SUBSCRIBE

PICK UP CURRENT ISSUE

Fifty-Six Cents: An Urban Vignette

Daniel Friedman

FROM ISSUE 31.1

Saturday 8th Dec 2012 ARCADE 31.1 Winter 2012

Photo by Jet Lowe, taken from the parapet of the World Trade Center, 1982, courtesy of Historic American Engineering Record, Library of Congress.

Among New Yorks many gifts to modern urban experience are neighborhoods famous for their colonization by artists, in whose wake eager, young, educated, art-loving connoisseurs followed, along with wealth, fashion, design and new cultural infrastructure. Displaced by the transformation of SoHo and Tribeca in the late 1970s, poorer artists crossed the river into Brooklyn, seeking refuge and affordability in its unreconstructed industrial fabric. For a time, I lived in one such neighborhood, a few blocks east of what is now called Dumbo (Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass), not far from the Navy Yard. My building sat on the northernmost and roughest edge of the remnants of Vinegar Hill, a nineteenthcentury neighborhood with no relation to vinegar (its name is an anglicization of the Gaelic Cnoc Fhiodh na gCaor, meaning hill of the berry-tree, honoring the site of a famous

battle during the 1798 Irish Rebellion). A few vestigial streets conserve its cobblestone and Federal and Greek Revival row houses, long since hemmed in by public housing and the Bronx Queens Expressway. I moved to this area after grad school when it was still hinterland, just as Dumbo emerged among the acronyms of New York developers, who soon took ownership. I relocated to New York in a grim economy with the highest unemployment since the Great Depression. I owed a few more months work to an NEA grant, finishing the project in nonprofit publisher, not far from the Museum of Modern Art. In the recession of the early 80s, finding an apartment in Manhattan was much harder than finding a job in architecture, which was nearly impossible. If firms were hiring at all, they werent hiring interns, especially interns with no practical experience or drafting skills. Even for the securely employed, an affordable apartment was hard to come by. Leases circulated in tight-knit social networks by word of mouth, people whispering addresses like smugglers. The only contact I had was my brother, who lived with his wife in the top-floor loft of a tenstory concrete warehouse, surrounded by rhizomatous transformers from the Con Edison Hudson Avenue Generating Station, which sprawled across the block. This building otherwise housed diverse low-end businesses and light industry, which we loosely called schmatta. In appearance and location, 160 John Street was a hole in the wall. The roof leaked, rendering the top floor unsuitable for manufacturing or textile work; however, roof leaks posed no problem for an expatriate Manhattan installation artist, who secured the 10,000 square- foot space as his studio; he sublet half of the space to my brother and sisterin-law, who sublet 1,000 square-feet to me.

Con Edison Hudson Avenue Generating Station, Brooklyn, NY. Photo courtesy of Andrea Cacciotti

Strictly speaking, no one lived on the tenth floor, we just all worked nights.

Imagine a long, narrow, rectangular volume 15 x 15 x 60-feet with a concrete floor exposed concrete columns and ceiling, zero amenities. The leaseholder had slapped together the interior walls defining my corner, leaving vast untaped planes of poorly anchored plasterboard to bow and list in the throes of imminent collapse. I had an old fridge and a single gas-fired space heater suspended from the ceiling in one corner to offset nonfunctioning radiators but no sink or toilet. I shared a kitchen and bathroom with the leaseholder on the other side of a hollow-core door I held closed with a spring and eyehook. Our kitchen featured a three-bay stainlesssteel darkroom sink, a gas range and a freestanding, counter-height butcher-block table. Our toilet sat in an unheated closet against an exterior wall. Our shower was a 4 x 4 x 2-foot plywood box clad in stainless steel, perched on sawhorses, draining to a PVC pipe the leaseholder jacked into the waste line under the sink. He suspended a showerhead from the end of a six-foot length of three-quarter-inch pipe connected to a garden hose wed attach to the sink faucet before turning on the water and clambering into the tub. Whether or not my neighbor was home, I almost always showered in the dark, three feet off the floor, in a 5,000 square-foot room. Life in the loft was raw but rewarding. Like the leaseholder, my brother and sister-in-law were artists who operated outside the illusory expectations of careerism. After months of living on potatoes and eggs, I finally found a temporary job that turned into full-time employment at McGraw-Hill. As the only tenant on our floor with steady income and a credit card, I filled my purpose. I commuted to work on the F Line, York Street to Rockefeller Center. Weeknights I took advantage of Manhattan; weekends we drove over to Brooklyn Heights for groceries and laundry; Sundays we gathered for ritual brunch in my brothers space, reading the Times and drinking strong coffee ground from whole beans and patiently filtered through the hour-glass of his Chemex coffee maker. In the summer, we repaired to a little deck on the roof where we basked in million-dollar views of lower Manhattan. Winters were rough. The buildings only elevator jammed. My car was stolen (and quickly recovered in nearby Williamsburg, exactly where an ex-detective from McGraw- Hills security department told me Id find it). Cockroaches nosed around with impunity. After a couple of years, I left the city for a teaching position in upstate New York. I loaded everything I owned into a small trailer, which I towed 400 miles to the edge of the Niagara Frontier, depositing its contents into my department chairs garage, which we sealed and fumigated. I last visited Dumbo in December 2010, for a meeting with Alicia Cheng, founding principal at mgmt. design on Washington Street. I saw what youd expect: city following culture. Today, the building I lived in is a self-storage warehouse. If you Google this address and zoom in on the surrounding fabric, youll see a single, giant stack hovering above the one remaining Con Edison steam boiler. Nowadays this complex is a brownfield-in-waiting. The Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy has set its sights on the plant, hoping to extend its program of shoreline remediation further north. Back in the 80s, the Hudson Avenue plant had four stacks, a huge tetrastyle portico on the rivers edge that made it easy to spot our loft from the air. On the verge of gentrification, not long after I moved out, a party of uncertain character purchased 160 John Street. Like many tenants in buildings bought for their promise of greater profit, my brother approached the new owner with an eye toward leveraging his sublease, to which the owner calmly replied, Mr. Friedman, why should I pay you twenty-thousand dollars when a

bullet only costs fifty-six cents?

Daniel Friedman has served as dean of the College of Built Environments at the University of Washington since July 2006.

Share this article:

BACK TO TOP

ISSUE ARCHIVE BLOG ARCHIVE EVENTS NEWSLETTER

SEARCH:

SEARCH >

ARCADE 1201 Alaskan Way, Suite 200, Pier 56 Seattle, WA 98101-2913

!"#

Terms of Use Privacy Policy Site by IF/THEN and Varyable

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- A Gaelic Blessing - Deep PeaceDocument4 paginiA Gaelic Blessing - Deep PeaceDraganVasiljevicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rules of ThumbDocument6 paginiRules of Thumbcanham99Încă nu există evaluări

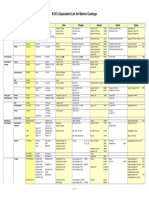

- Coating Equivalent List KCCDocument3 paginiCoating Equivalent List KCCchrismas_g100% (2)

- Citizen Kane Script by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles PDFDocument135 paginiCitizen Kane Script by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles PDFFlavio Roberto Mota100% (2)

- Symbols and ArchetypesDocument36 paginiSymbols and ArchetypesRangothri Sreenivasa Subramanyam100% (2)

- Solid Edge ShortcutsDocument3 paginiSolid Edge Shortcutsabekkernens100% (1)

- TBT 03 Plan To Help A Friend Flannel Graph Color enDocument8 paginiTBT 03 Plan To Help A Friend Flannel Graph Color enMyWonderStudio100% (64)

- Materi Periods of English LiteratureDocument7 paginiMateri Periods of English Literaturetika anoka sariÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Thessalonians 5:12-28 Dennis Mock Sunday, FebruaryDocument4 pagini1 Thessalonians 5:12-28 Dennis Mock Sunday, Februaryapi-26206801Încă nu există evaluări

- Four H Group: SL Particulars Quantity RemarksDocument3 paginiFour H Group: SL Particulars Quantity RemarksrzvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leave RecordDocument50 paginiLeave RecordDiyanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- History VillaDocument22 paginiHistory Villaasyikinrazak95Încă nu există evaluări

- Sole Proprietory FirmsDocument21 paginiSole Proprietory FirmsHuzeifa ArifÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vocabulary Quiz Lesson 3the Case Unwelcome Guest Part 1 2017Document6 paginiVocabulary Quiz Lesson 3the Case Unwelcome Guest Part 1 2017Angela KudakaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Readme (Password + Instructions)Document3 paginiReadme (Password + Instructions)Jesus Roberto Aragon LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Power Plus Air 2009Document12 paginiPower Plus Air 2009Thim SnelsÎncă nu există evaluări

- On The Genealogy of Art Games - A PolemicDocument104 paginiOn The Genealogy of Art Games - A PolemicJosé Ramírez EspinosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hindustan Photo Films' manufacturing processDocument7 paginiHindustan Photo Films' manufacturing processSridhar SriÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Witcher Romance - Witcher Wiki - FANDOM Powered by WikiaDocument4 paginiThe Witcher Romance - Witcher Wiki - FANDOM Powered by WikiaEduardo GomesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pradosham: An Important Saivite Worship Ritual Observed in Lord Shive Temples in IndiaDocument4 paginiPradosham: An Important Saivite Worship Ritual Observed in Lord Shive Temples in IndiaMUTHUSAMY RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arts-Informed Research - Cole, KnowlesDocument16 paginiArts-Informed Research - Cole, KnowlesGloria LibrosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paket 9 Big UsbnDocument13 paginiPaket 9 Big UsbnMia Khalifa100% (1)

- Doctor 8Document16 paginiDoctor 8Pankaj GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Ethos in Management-The BibleDocument12 paginiIndian Ethos in Management-The Biblenoor_fatima04Încă nu există evaluări

- RHRSC Recursos Humanos y Responsabilidad Social Corporativa McGraw HillDocument7 paginiRHRSC Recursos Humanos y Responsabilidad Social Corporativa McGraw HillSandra Kalandra Ptanga0% (1)

- Photogrammetry2 Ghadi ZakarnehDocument138 paginiPhotogrammetry2 Ghadi ZakarnehTalha AtieaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 675 - Esl A1 Level MCQ Test With Answers Elementary Test 2Document7 pagini675 - Esl A1 Level MCQ Test With Answers Elementary Test 2Christy CloeteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Variations Within SupersessionismDocument18 paginiVariations Within SupersessionismAnonymous ZPZQldE1LÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Audio Tale of Revenge and DeceptionDocument27 paginiAn Audio Tale of Revenge and DeceptionSara Lo0% (1)

- 37 Best SmsDocument12 pagini37 Best SmsSandeep KumarÎncă nu există evaluări