Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

102 Occupational Therapy For Physical Dysfunction

Încărcat de

Patricia MiglesDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

102 Occupational Therapy For Physical Dysfunction

Încărcat de

Patricia MiglesDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

"

I

(

,I

'"

I

j

1

J

i

J

I

1

I

I

I

\

f

I

&earnceO. Wau!>. 1.1("

Occupational

Therapy lor

Physical

Dysfunction

Fourth Edition

Editor

A. TroDlhJy

O.T.R.,F.A.O.T.A.

Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy

Sargent College of Allied Health Professions

Boston University

Boston, Massachusetts

Williams &

HO,NG KONG

teNDON. MUN!CH SYDNEY" TOKYO

A W",VI::RlY COMPAN Y

NCSStudyGroup

ScientificInquiry

8/05

DonStraube,PT,MS,NCS

Topicscovered:

Theorydevelopment

PrincipalsofMeasurement

Sensitivityandspecificity

Reliability

Validity

Researchdesigns

Experimental

Quasi-experimental

Single-subject

Parametricandnonparametricdata

Descriptivestatistics

Statisticalinference

Analysesofvariance

Analysesof frequencies

Correlation

Regression

Epidemology

1

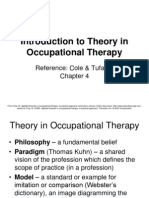

Theory Development

Theory: an abstract idea or collection of ideas used to explain physical or social

phenomenon. See Figure.

Theories are not directly testable, but hypotheses are. Researchers set up

hypotheses based on the theory> collect data > statistically analyze / test the data

> interpret the results and either support our hypothesis (and indirectly the

theory), or don't support our hypothesis and theory (positivism approach).

We use theoretical frameworks I paradigms to help describe theory and

influencing factors and underlying assumptions.

Basic tenets of a theory:

1. Evolves from experience / research

2. Dynamic-

Newtonian Physics to Theory ofRelativity

3. Not directly testable

4. Requires scope conditions - conditions or situations under which the theory will work.

5. Requires operational definitions - ofthe major constructs ofthe theory (e.g., tone,

normal movement). When operational definitions are absent, then there is disagreement

among researchers (lack of consensus related to phenomenon).

Principals of Measurement

Measurement: the process ofassignin numer to objects to represent quantities of

to certain rules. ere is a difference between numerals and

numbers!!! umb ve conjoiqt additivity (can addlsubtract/multiply/divide and

maintain meaning of numbers). Numerals do not have this!!! This is important to

consider when applying statistics ... for example the FIM. This limitation is overcome by

models associated with Item Response Theory (Rasch Measurement Model, 2 & 3

parameter models).

Scales

Nominal: objects or people are assigned to categories based on some cri,erion.

(e.g., yeslno, OIl, present/absent). Uses vs numbers!!! I (l.Au:.:

Ordinal: categories are rank-ordered on the basis of an operationally defined

characteristic. Higher levels usually respond to "more" of the construct of

interest. Uses - not numbers! !

(e.g. 0-10 pain scale, FIM, Berg Balance Scale, MMT)

Interval: has the rank-order characteristic ofan ordinal scale, but also equal

intervals between response categories. These are not related to a true zero, so not

representing an absolute quantity. (e.g., temperature, IQ, ROM). Involves

numbers .

...----

2

Ratio: numbersrepresentingunitswithequalintervalsandhave~ (e.g.,

age,bloodpressure,dynamometer). Involvesnumbers.

Thetypeofdatayouhavewilldictatethetypeof statisticsused. Non-parametric

statisticsareusedfornominal!ordinaldatainwhichthedataarecomposedof numerals.

Parametricstatisticsareusedforintervalandratiodatainwhichthedataarecomposedof

numbers.

Sampling

Samplinginvolvesselectingsubjectsthatarerepresentativeof thepopulationof

interest. Inclusion!exclusioncriteriaareoftenusedtopickthestudysUbjects. Random

samplinghelpstoincreasetheabilitytogeneralizefromthestudypopulationtothe

targetpopulation,asthesamplesarethoughttobemorerepresentativeofthegeneral

popUlation.

Probabilitysampling

Simplerandomsampling

Systematicsampling

Samplingintervalsused

Non-probabilitysampling

Conveniencesampling

Quotasampling

3

Sensitivity I Specificity

When a measurement tool is intended to be used to screen patients for the presence or

absence of a condition (e.g., risk for falling), then the understanding ofthe test's

sensitivity I specificity is important.

Sensitivity: ability of a test to obtain a positive result when the condition is present (true

positive). Sensitivity is more important when the risk associated with missing a condition

is high.

Specificity: ability of a test to obtain a negative result when the condition is absent (true

negative). Specijicity is more important when the risk associated with further

intervention is substantial.

Tests are never both high in sensitivity and specificity, but rather a trade offoccurs.

When possible, using tests that compliment each other is helpful.

Diagnosis

Dx+ Dx-

Test Results

Sensitivity =a I a + c Specificity = d / b +d

Reliability: the extent to which a measurement is consistent and free from error

.;.NA 0{

,:p Types of reliability

; AJI

Observed score =true score + error

Sources oferror: individual! instrument! variable being measured

Intrarater reliability: same person perform measure over time

'pr Assesses error from the individual and variable being measured

Interrater reliability: different people measuring same thing

Assesses error from individual

Test-retest reliability: repeat measures on same sample on two different occasions

Assesses if error from the instrument / variable being measured / rater

Internal consistency: concerned with the extent to which the items of an

instrument measure the same characteristic. Different from validity!

Split half reliability

Cronbach's alpha

4

Statisticsforreliability

Kappa K ,- }ttnrlilJ ctif

fPfh6 10

WeightedKappa h.-; ::;.

::t:ec, Lj, 0

_I..ll

ICCvs .

c

/0

Howwouldyoudesignaclinicalstudytoassessthevariousreliabilitiesofa er

I

commonlyusedtest(eg.,ROM,MMT,BergBalanceScale,etc)?

q

r; '''l--

Inter-raterreliability "1

3 Ct

Q &.uz..,

tf

"2>

/f

,.

"1-

J

Intra-raterreliability

Considerissuestopopulationspecificity..

5

Validity

Face:weakestform ofvalidity- doestheinstrumentmeasurewhatitissupposed

tomeasure? Basedon"expert"opinion- isthemethodplaUsible?

Construct:establishestheabilityof aninstrumenttomeasureanabstract

constructandthedegreetowhichtheinstrumentreflectsthetheoretical

componentsoftheconstruct. (Correlationof motorskilldevelopmentwithage).

Striveforinstrumentsthatareunidimensional- measureoneconstruct(FIM).

Supportedby:knowngroupsmethod,discriminantvalidity(CPl),factoranalysis,

IR Tmethods (fitstatistics)

Content:Indicatesthattheitemsthatmakeupaninstrumentadequatelysample

theuniverseof contentthatdefinesthevariablebeingmeasured. MostusefulforI

duringthedevelopmentofquestionnairesandinventories. (e.g.Testofmath

ability- butwordbasedproblems). Usuallyagreeduponbyexpertsinthearea.

Criterionrelatedvalidity:indicatestheoutcomeof oneinstrument(targettest)

canbeusedtosubstitutemeasurefora"goldstandard"criteriontest. (ROMI

radiographs) Canbeconcurrentorpredictive.

Concurrent:estabilishesvaliditywhentwomeasuresaretakenatthesame

time. (e.g.RIC-FASandFIM,FunctionalReachTestandposturalsway

measuresfrom aforceplate)

Predictive: establishesthattheoutcomeofthetargettestcanbeusedto

predictafuturecriterionI score. (e.g.BergBalanceTest,Functional

ReachTest)

ConsiderI discussthevalidityofthesetests: MMTI AshworthScaleI ROMI

FIMI anyothers?

Considerissuesrelatedtopopulationspecificity.

~

6

~ Research Design

Characteristics may include:

Independent variable I dependent variable

Random assignment

Manipulation of variable (IV)

Control groups

Research protocol

Blinding of investigator and subject (double-blind) or just one group

(single-blind) to eliminate biases

Issues:

Internal validity: potential for confounding factors to interfere wl

The relationship between IV /DV. (maturation I testing I attrition)

External validity: extent to which results can be generalized

outside of experimental situation. (random sampling I assignment

help).

Experimental Design: uses random assignment to at least two comparison groups

and controls for threats to internal validity. Strongest evidence for casual

relationship.

Think of a study that would represent I include an experimental design .....

Quasi-experimental Design: lacks random assignment and I or 2 comparison

groups.

Think of a study that would represent I include a quasi-experimental design ..... .

Single subject design (see handout I Figure)

Repeated baseline measures: subjects serve as their own controls.

7

Descriptive Statistics

~ f central tendency

/ ean - total score! # in sample

~ ~ if' Mode - most commonly occurring score

~ Median - value that represents the 50% in ranked distribution

~ Range - dispersion equal to difference between highest & lowest scores

Standard deviation - value used to describe the variance in the data

= square root of sum (X - mean)! N))

X - mean =deviation

Sum ofdeviations = sum (X-mean)/N

8

ParametricI NonparametricStatistics (seehandouts/Figures)

SampleDistribution

z-Scores:usedtodescribethelocationof anindividualscoreinadistributionandallows

forcomparisontootherdistributionsthathavebeentransformed

z=X-mean

SD

Allowsustosayindividualwas+/- oneortwostandarddevabovelbelowmean.

Confidenceintervals/significancelevels(alphalevel). Thesearesetapriori-

aheadoftimefortestof significance.

TypeIerror- falselyrejectthenullhypothesis.

TypeIIerror- falselyendorse/retainthenullhypothesis.

Parametric ... AO g..

Assumptions"

>( iYJ. Nomaldistribution,equaldistribution,interval/rationdata

T-test,ANOV A, etc

V\ Man-WhitneyUTest,SignTest,Wi1coxonMatch-PairsSigned-Rank 'r

Test,Kruskal-WallisTest

OAltJ 1.10 P ell sIT-l

I V---..

-

9

StatisticalInference

Whatcanbeinterpretedfromtheresults?

Haveassumptionsbeensupportedorviolated?

Nonnaldistribution

Intervallevelscore

Appropriatesamplesize

AnalysesofVariance

Comparisonof>2means(vsTtestisfor2means)

One-wayANOVA

Two-wayANOVA

Analysesoffrequencies

Frequencydistributiontable

Frequencydistributiongraph

Histogram

Bargraph

Polygon

Symmetricaldistribution

Positivelyskeweddistribution

Negativelyskeweddistribution

Quartiles

10

Correlation

Mathematicalmethodforassessingrelationshipamong2ormorevariables(DV

totheIV). Correlationcoefficientsrangefrom-1.0to 1.0 Shouldnotbeinterpretedas

cause& effect. Onlyassessmentofrelationshipamongvariablesundervarious

conditions.

Positivecorrelation

Negativecorrelation

Regression

Multipleregression

Assessingtherelationshipof>2independentvariablestothedependent

variable. AbletosayindependentvariableXlexplainsX%oftheDV,X2. .. "

explainsX%oftheDV,etc. TheDVisacontinousvariable. J

Logisticregression

Sameasmultipleregression,butwithlogisticregression,theDVisa

discretevariable.

Epidemology studyofthedistributionanddeterminantsof disease,injuryordysfunction

inhumanpopulations.(egcausalfactors,riskfactors). Helpfulwhencharacterizinga

diseaseI epidemic.

Incidence- quantifiesthenumberofnewcasesofadisorderordiseaseinthe

populationduringaspecifiedtimeperiod.

Prevalance- proportionreflectingthenumberof existingcasesofadisorder

relativetothetotalpopulationatagivenpointintime.

11

CHAPTER 2. THE ROLE OF THEORY IN CLINICAL RESEARCH 19

ting on how

aning to iso-

bservations. .

my separate

otorcompo-

Il'e also used

tance, a the--

U\d feedfor-

skill.

cumstances.

)lace during

ingleaming

II\ isoldnetic

rqueoutput

tostrength

ltcannotbe

'Ories,New-

nologywas

measure of

:plains how

)re( . how

n,

tohygiene.

idingmoti-

: a theoreti-

hypothesis

the theory.

a therapist

1 patient to

,hodoand

encetothe

Il\e theory.

! results of

monstrate

yexamin-

scientific

Figure 2.1 A model of scientific thought, showing the circular relationship between facts and

theory and the integration of inductive and deductive reasoning.

The basic building blocks of a theory are concepts. Concepts are abstractions that

allow us to classify natural phenomena and empirical observations. From birth we

begin to structure empirical impressions of the world around us in the form ofconcepts,

such as "mother," "father," "play," or "food," each of which implies a complex set of

recognitions and expectations. We develop these concepts within the context of

ence and feelings, so that they meet with our perception of reality. We supply labels to

sets ofbehaviors, objects, or processes that allow us to identify them and.discuss them.

We use concepts in professional communication in the same way. Even something

as basic as a "wheelchair" is a concept from which we distinguish chairs of different

types, styles, and functions. Almost every term we incorporate into our understanding

of human and environmental characteristics and behaviors is a conceptual entity. When

concepts can be assigned values, they can be manipulated as variables, so that their

tionships can be examined. In this context, variables become the concepts used for

building theories and planning research. Variables must be operationally defined, that

is, the methods for measuring or evaluating them must be dearly delineated.

Some concepts are observable and easily distinguishable from others. For instance,

a wheelchair will not be confused with an office chair. But other concepts are less tangi-

ble, and can be defined only by inference. Concepts that represent nonobservable

behaviors or events are called constructs. Constructs are invented names for variables

that cannot be seen directly, but are inferred by measuring relevant or correlated

iors that are observable. The construct of intelligence, for example, is one that we cannot

see, and yet we give it very dear meaning. We evaluate a person's intelligence by

observing his behavior, the things he says, what he "knows." We can also measure a

person's intelligence using standardized tests and use a number to signify intelligence.

I

A B A B

180

160

Z 140

20::

~ ~ 120

...1...1

LL.:=I 100

LL.0

0%

tn en 80

wl-

~ : : i 60

(,!)..J

W 40

o

20

1 I I I

i i i , i I i lii i I1 i i lii i I i i I i

2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24

DAYS

FIGURE6-1.ThebasicARABdesign.

8

A

3.0

Cl

w

~ 2.5

...Itn

~ w 2.0

...I

wi 1.5

(.)

zz

.c- 1.0

l-

tn

0.5

Q

2

4 6 8

10 12 14

DAYS

FIGURE6-2.TheABdesign.

(

,

MEDICALTRWSBF.SEd

A B A

FIGURE6-3.TheABAdesignandoverlap.

I

would be very difficult to defend against the possibility thatsomeunC(

variableaccountedforanychangeobservedinthedependentvariable.Ft

pie,a changeintheweathercoincidenttotheinitiationoftreatmentmil

causedtheobserved (orself.reported) changeinwalking.

TheABAdesign (Figure &-3) is strongerbecausethedependent\la

clearlyassociatedwiththeinitiationandwithdrawalof trealment.TheABA;

(Figure6-1),however,isstillstronger;asHersenandBarlowpointout,"Ul

naturalhistoryofthebehaviorunderstudyweretofollowidenticalfluctw

trends,itismostimprobablethatobservedchangesareduetoanyinfluen

somecorrelatedoruncontrolledvariable) otherthanthetreatmentvariab

systematicallychanged"\! (p.176).

There are two problems associated with withdrawal designs (ABA.

Thefirstpotentialconcernisthatsomebehaviors,bytheirnatureorbecau

subject'sresponse,donotreverttotheinitialbaselineoncegainshavebee

For example, in Figure 61 the second Phase A did notrevert to the

measurementbutthe trend did level off. Whether this is a realproblen

mustbeanaIyzedrationallyineachexperiment.Learning,especiallymob

ing,isanexampleofavariablethatisnotlikelytoreverttoanoriginalha

ashortperiodoftime.

Thesecondconce.rnis theethicsofwithdrawing3C "tmentthat81

beeffective.Onemayarguethataperiodofwithdrawr' legitimately

inthecauseof avoidingfalsepositiveinitialresultsthat..." .Jleadtothec

.. '!

2.3 I FREQUENCY DlS1RfBUTION GRAPHS

~

DEFINITION Fora bar graph, a verticalbarisdrawnaboveeachscore(orcategory)so

that

1. Theheightofthebarcorresponds tothefrequency.

2. Thereis a spaceseparatingeachbarfrom thenext

Abargntphisusedwhenthedataaremeasuredonanominaloranordinalscale.

FREQUENCY DISTRIBUTION

POLYGONS

Insteadofa histogram,manyresearchersprefertodisplayafrequencyd i ~ o n

usinga polygon.

DEFINITION Inafrequency distribution polygon, a singledotis drawnaboveeachscore

sothat

1. Thedotiscenteredabovethescore.

2. Theverticallocation (height) ofthedotcorrespondstothefrequency.

A continuouslineisthendrawnconnectingthese dots.Thegraphiscom-

pletedbydrawing a linedowntotheX-axis (zerofrequency) ata pointjust

beyondeachendoftherangeofscores.

FIGURE 2.3

Anexampleofafrequency distribution

histogram forgroupeddata.Thesameset

ofdataispresentedinagrouped fre...

quencydistributiontable andin ahisto-

gram.

X f

5

12-13 4

10-11 5

8-9 3

6-7 3

4-5 2

i:

4

0'----

2-3 4-5 6-7 8-9 10-11 12-1314-15

Scores

FIGURE 2A

Abargraph showing the distribution of

personalitytypesinasampleofcollege

students. Becausepersonality type is a

discrete variablemeasuredonanominal

scale. thegraphisdrawn with spacebe-

tween thebars.

20

~ 15

~

0'" 10

~

u.

A B c

Personall1ytype

/-""

\ f

\.,. ~ /

X

6.6

Followingaz-scoretransformation,the

X-axis is.relabeledinz-scoreunits.The

distancethatisequivalentto 1standard

deviationontheX-axis (a == 10pointsin

thisexample)conespands to 1pointon

thez-scorescale.

80 90 100 110 120

t..d I

z

-2

-1 0 +1 +2

JI.

6.2 I PROBABIUTVAND THE NORMALDlS1RIBUDON

FIGURE6.4

Thenormaldistributionfollowing a

,-scoretransformation.

2.28%

-2 -1 0 +1 +2

J1

198 CHAPTER 8 I INTRODUCTION TO HYPOtHESIS1'ES11NG

FIGURE8.4

The locationsofthecriticalregion

boundariesfor three differentlevelsof

.significance: Cl = .05, Cl = .01, and

Cl = .001.

-1.96 0 1.96

-2.68 \ ) 2.68

----a=.001----

1

/\

IATION OF CLINICAL PRACTICE DESCRIPTIVE RESEARCH

TABLE 5-2 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

101

research. As indicated in

p in the research process.

with the literature to find

problem, it takes on some

etative t'eview of literature

.luating the quality, or the

her colleagues

60

"decided

udies. In this way, conclu-

drawn from the best meth-

.1 anciskin disorders has been

:linical trials (RCTs) involving

ne were generally of a better

:0 clear relationship could be

l the efficacy of laser therapy,

In general, the methodological

:onsequently, no definite con-

lerapy for skin disorders. The

1&5 seems, on average, to be

re specifically, for rheumatoid

cial pain, laser therapy seems

rther RCTs,;( , "ling the most

rto enable tJt.... .;nefits of laser

Level of Central Spread or

Measnrement . Tendency Variability Other

Nominal Mode Range Frequency counts and

percentages in

categories

Ordinal Median Range Frequency counts and

percentages at levels

(percentile)

Range; variance; Frequency counts and

~ Mean

standard . percentages at levels

deviation

......\

.. . ~

list, the range would be 0 to 3. There are two Os, seven Is, two 2s, and five

3s; therefore, the mode would be 1 because there are more Is than any

other number. The mode is a measure of central tendency for nominal

data. A sample may be bimodal if two frequencies are equal in number.

The frequency counts can be transformed into percentages. For example,

the Os make up 12.5 percent (1/8) of the total list; percentages should,

however, be used with caution when the sample (n) is small.

The median is the statistic of central tendency of a set of ordinal data;

it is the middle of the range of recorded measurements, listed in order. For

example, take all of th( '-jngs of spontaneous activity in the supine posi-

tion from the table in -:.. .:! article by Carter and Campbell. Sixteen ratinszs

~

!

--- - -- -. .... _.. ....-_............,.... ...""

he practicingclinicians.

)anything done for the

ts physiological orpsy-

)gical effectsonpatients;

cal effectsofthemodal-

underwhatcircum-

ithologydoes it change

age, the frequency, the

Iftreatment?Whatisthe

lrticular case, and what

Whatarethesideeffects

1, orintensity?Giventhe

do the answers change

eyinteractandinfiuence

youwereworkingand

latyouwereapplyingto

Ilyasanswers?Thepoint

Iberofclinicalquestions

)esigns using sequential

answer these questions

dgn has been little used

ture.ReadLightandcol-

Jnentsof thedesign dis-

llt.

23

"

ldation and the manner of

datedwitheverystatistical

test is valid under certain

(

tests.

25

Table8-3outlinesaselectnumberotClasSIC statiStiCal

defined ,above. Afrequently used statistical test is listed for each mea-

surement level and for eachsampling model given in Table 8-1.As dis-

cussedin Chapter3,parametri<:statistics,r.efeitotl?-ose'testsappropriate

fo-:jnettIcda. tests,espeCially andFtest,rnat<e

normallydistributed

asonthe'farnlliarbell testsmakefewer

andsoaremotewidelyapplicabl*26Nonparametrictestsmaybeapplied

tometric data,iftheassu,mptions'of the parametric testsarein question,

butit is nofappropriatetoapplymetricteststonominalorordinaldata.

More complexdesigns for k datasets,factorial designs, andmultivariate

designs will beillustratedinChapter9.

TABLE 8-3 STATISTICALTOOLSAPPROPRIATETO EACH

BASIC'RESEARCH DESIGNAND LEVEL OF MEASUREMENT

Level ofMeasurement

TypeofDesign Nominal Ordinal Metric

1. Onesample 'Ohi"Sqriarelx2) ,i One-sampleruns Hest,related

2. Two related,own McNemar Sigri test Hest,related

control Wilcoxop.

3. k related,own CochranQ FriedMaa Ftest,two-way

control AOV

4. Two independent X2, Median test t-test,indepen-

Mann-Whitney dent

5. Two related, McNemar Sign test t-test,related

matched WilkOXGD

6. k independent X2, Kruskal-Wallis Ftest,one-way

AOV

7. k related,matched CochranQ FriedmaI1!$! Ftest,two-way

AOV

AOV =analysisofvariance.

Sources:Datafrom Campbell.DT andStanley,JC: Experimental andQuasi-Experimental

Designs for Research,Rand-McNally, Chicago, Daniel,WW: AppliedNonpara-

metricStatistics.HoughtonMifffin, Boston, 1978.

I

1rO-I : ( ..,Scri"....

I

PubMed

PubMed, created by the National Library of Medicine, provides access to: MEDLINE and PreMEDLINE.

Compose Your Search: Define your search clearly; consider all important words, concepts, and synonyms.

Su bj ect Searching: PubMed may be searched by entering keywords or phrases into the text box. You may

enter one or more terms and press the enter key or click Go. PubMed will search multiple words as a phrase if it

recognizes the terms. Otherwise, PubMed will search the words separately and combine with AND. PubMed will

also automatically try to map your term to a MeSH heading.

Use "OR" or "AND"to combine your concepts. OR broadens a search (e.g. Breast Neoplasms OR

Breast Diseases) AND narrows a search (e.g. Vitamin C AND common cold)

Database: MeSH terminology provides a consistent way to retrieve information that may use different

terminology for the same concepts. One way to select MeSH terms is to use the MeSH Database link, found on the

blue sidebar, to browse for appropriate terms. Enter the term in the text box and click GO.

View the list ofterms that appears and click on the most appropriate term.

Scroll down the page to see everywhere the term appears in the MeSH "Trees," a hierarchial subject category display

ofMesh terms. For example, ifyou browse this listfor eating disorders, you can select.from a host ofterms including

Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia and Pica.

To further refine your search, limit your search by using Subheadings, Major Topic or Explode.

Do Not Explode. To decrease retrieval, click on the Do Not Explode checkbox to not include MeSH terms

found below your term in the MeSH tree.

Major Topic. Click on Major Topic to limit search to citations in which your term is the main topic.

SubHeadings. Click in any of the subheading checkboxes to further narrow your search term.

Chemically Induced Complications Diagnosis

Drug Therapy Epidemiology

Click "Send To" when done narrowing the term. Continue to add terms to your search using the MeSH

database. When complete, click Search PubMed

Title Word Search: Limiting a search to a word found in the title of articles is often a good way to reduce large search

results. You can do this by entering the term in the text box. Then click on Limits, pull down the All Fields menu, and

select Title Word. You may also limit to title by entering the term followed by [tiJ.

Author Search: The Index provides a list of author names and variations. To use, click on Preview/Index found

below the textbos. Scroll down the page to Add Term(s) to Query or View Index. Using the All Fields pull-down

menu select Author Name. In the text box, enter the author's last name and initials ifknown. Click on INDEX.

Selec:t the name from the list of options that appears. Multiples names may be selected by holding down the CTRL key.

Multtple names will be ORed together. Names can be added to tlle search box by clicking AND (to combine) OR (to

find either/or), or NOT (to exclude). '

Journal Name: To retrieve articles in specific journals, use the Index. Follow the Index instructions for searching by

author (above), and select Journal Name from the All Fields pull down menu

your Terms. PubMed will provide the results of your search in the History Table. PubMed will also

proVIde a nUl11ber for each ofyour search terms or sets. You must use the # symbol before the search numbers and

search operators (AND, OR, NOT) must be capitalized

Sgarch

#3 E:carch#l AND #2

#2 St:i:lIl;l! u.n:rl aglmLs

#1 :search diabetes mellitus llon-insuJin dependent/droll therapy

Limit: searchfurtherbyclickingLimits. ThiswillallowyoutolimityoursearchbyJournalSubsets,Age

Groups,PublicahonTypes,andotherfeatures specifictothedatabases.

DisplayingSearchResults:PubMeddisplayssearchresultsinbatches;thedefaultis 20records perpage. To

change .default, theShowpull-down to thenumberofrecordsdisplayedonasinglepageupto

500. TIns IS aconvementwaytobrowsetheenhredisplaytochooseselectedarticlesto saveorprint.

PubMedcitationsinitiallydisplayin Summary (Author,Title,Journal,PubMedID)format. Documentscanbeviewed

inotherformatsincludingBrief(author,PubMedID),Abstract(Author, Title,Journal,PubMedID,Abstract),

Citation(Author,Title,Journal, PubMedID,Abstract,MeSHHeadings), and MEDLINE(forimportingintocitation

software Author,Title,Journal,PubMedID,Abstract,MeSHHeadings).

SavingResultstoDisk: Resultsmaybesavedtoadiskorharddrive. OncesearchresultshavebeenDisplayedin

thedesiredformat(Summary,Brief:Abstract,Citation,orMEDLINE),select"File"fromthepulldownmenunext

to "SendTo". NextclickSendTo. A SaveAsDialogBoxwillappear. TitlethenameofyoursearchintheFile

NameBox. ClickSave. ThesefilescanbeopenedinWord,WordPerfect,orNotepad.

SavingtoCitationSoftware (ReferenceManager,Endnote)

ToimportresultsintoCitationSoftware,youmustdisplayyourresults inMEDLINEfOID1at Select"File"fromthe

pulldownmenunextto"SendTo". NextclickSendTo. TitlethenameofyoursearchintheFileNameBox. Click

Save.

EmailResults: OncesearchresultshavebeenDisplayedinthedesiredformat(Summary,Brief:Abstract,

Citatiou,orMEDLINE),clickonthepull-downmenunexttoSendTo. Select''E-Mail''andclickonSendTo. In

thetextboxnextto"E-mail"enteryouremailaddress. ClickMail.

ClipBoard:TheClipboardallowsyoutogroupselectedcitati,onsfromoneormoresearches.Amaximumof500

citationscanbeplacedintheClipboard.Clipboarditems.willbe.1ostafteronehourof inactivity.Toadditemstothe

clipboard,clickonthecheckboxtotheleftofthecitation'andSelect"Clipboard"fromthepulldownmenunextto

"SendTo". NextclickSendTo.OnceacitationhasbeenaddedtotlleClipboard,therecordnumbercolorwill

changetogreen. OnceyouhaveaddeditemstotheClipboard,youcanclickonClipboardfrom theFeaturesbarto

viewyourselections. .

SavingSearchStrategies& TheCubby:TheCubbyisusedtostoresearchstrategies. To register,clickonCubby

fromthePubMedsidebar. Nextclick"IWanttoRegisterforCubby." FillintheformprovidedandclickRegister.

ToStoreaSearchintheCubby: Run thesearch. ClickonCubbyfromthesidebar. (Loginifyouhaven'talready

doneso.) Inthemiddleofthescreenatextboxunder"CubbySearchName" willappearWitllyoursearchstrategy.

Youcaneditthematerialinthetextboxtoameaningfulnameforthesearch.

ToRunaSavedSearchedStrategyintheCubby:ClickonCubbyfromthePubMedside. Clickonthecheckbox

nexttothesearchyouwanttorunandclick"What'snewforselected."

LinkOuts:UICsubscribestonumerousonlinejournalswhichmaybeaccessedthroughPubMed'sLinkOuts. Once

yoursearchiscomplete,clickonAbstractsintheDisplaypulldownmenu. Thiswillshowtlleabstractsof thearticles

andavailablelinkouts. IfyouhaveenteredPubMedthroughaUICLibrarywebpage,itemsownedbyUICwillbe

accompaniedbyanIconindicatingUICholdingsinformation.

Indicatesthatyoumaylink directlyto thejournalarticlefromPub Med.

.Qf___:lW: JJS

. Print holdings' IndicatesthatUICholdsthisj0U111a1 inPrint. ConsultlITCCATformorein-depthholdings

for UIC users infunnation. .

Note: NotallofUIC'sonlinejoumalsareaccessibledirectlythroughPubMed. In addition,notall ofthelinkoutsin

PubMedareaccessibletoUICusers.

ForFutherAssistance,pleasecontactReferenceStaff.

SDG09/03

o V I D CINAHL WEBONLINESEARCHING

I

I

Compose Your Search

Defineyoursearchclearlyand concisely; considerall impOltantwords, concepts,andsynonyms.

Enteryourkeywordorphrase(e.g. eatingdisorders).

CINAHLwill automaticallytryto mapyoursearchtennto asimilarorrelatedtenn(s). Ensure the MapTerm

Checkboxis checked.

Ifanyof thetermsCINAHLlistsappearappropriate,you canclickontheSelectcheckboxforanyor

all oftheterms.

Ifyou choose morethanonetenD, usethepull-downmenuatlhetopofthepageto

combinethemwith"OR",or"AND".

ORbroadensasearch(e.g. friendships orpeerrelationships)

AND nalTOWS asearch(e.g. EatingHabitsandBodyhnage)

" ,

Explode. Toincreaseretrieval, OvidautomaticallyExplodesselectedtennstoincludeanynalTowertermsor

concepts. (e.g.Exploding"EatingDisorders"willincludethenalTowertenns: Anorexia,Bulimia,andPica.)

Focus. ClickontheFocuscheckboxto limityoursearchtocitationswhereyourtermisthemaintopic.

IfyouonlyselectedonetennfromthelistofSubjectHeadingsprovided,CINAHLwillpromptyouto

choosesubheadingsfor yourtenn.

Subheadingsfor: Eatingdisorders

OChemicallyInduced(3) oDiagnosis(46) OEducation(7)

OComplications (23) ODmgTherapy(8) OEpidemiology(32)

Youcanclickinanyofthesubheadingcheckboxesto :fi.uthernarrowyoursearchtermORclick

Continue(nosubheadingswillbeselected).

If CINAHLwasunabletoprovidealistof relatedtennsforyoursubject,trytothinkofotherrelated

tennsandrepeatthe abovestepsORclickofftheMapTerm Checkbox.

CINAHLwillprovidetheresults ofyoursearchinthetableentitledSearchHistOJ)I. CINAHLwill also

provideamunberforeachofyoursearchtenTIS orsets.

EntertllenextkeywordorphrasethatyouwouldlikeCINAHLtosearch.Thenamesofauthors,journals,or

titlesmaybesearchedbyclickingontheappropriate icon.

Enterthefirstfewlettersofafulljournalname; donotuseabbreviations(e.g. BehforBehavior

Journ"J Modification). ClickPerformSearch.CINAHLwillprovidealistofJournalTitles. Clickonthebox

nexttothetitleyouaresearching.

Enterawordorphrasetobesearchedinthetitle (e.g. reportingof medication).

Entertlle Author'slastname,aspace,and firstinitialifknown (e.g. WinslerA). ClickonPerform

Search.CINAHLwillprovidealistof Authors., Clickontheboxesnexttotheauthors'namesthat

AuttJor appeartobetheonesyouaresearching.

Combine your Terms.

Oombine

CombineyoursearchtermsusingtheconnectorsANDand OR. Usethenumbers that CINAHL

providedintheSearchHistorytable.

# Seal1:hHistory ReSw.ts Display

Demetlual 1046 Display

2 Conceptanalysis/ 287

3 3 Display

_ a Limit

r ~ LimityoursearchfurtherbyclickingontheLimiticon. Thiswill allowyou tolimityoursearchby

Limit Language,PublicationYear, PublicationTypeandotherfeaturesspecifictothe databases.

Examine Your Search Results

CINAHLautomaticallydisplays theresults ofthelastsearchatthebottomof thescreen. Usethe scrollbarto

examinetheresultsof yoursearch. Youcan alsoclickonDisplaytoviewtheresults.

ClickonAbstractorCompleteReferencetoviewtherecordindetail. SomecitationsinCINAHLalso

contain thefulltextarticle. Ifavailable,you can clickonFullTexttoseetheentiremticle.

Print, Download or E-mail Full Text

Clickon"OvidFullText"whereavailabletolinktoarticlesavailablefull-textthroughOvid. Scrolltothe

OutputBoxfoundnearthe topontherightsideof thepage.

ToPrinttheFullTextof anarticle,clickonthePrintPreviewIcon. SelectaGraphicSizeandclickContinue.

ThenclickonthePrinticonfoundonyourWebbrowser. ClickFullTextPDFtoobtainarticleinPDFformat

whenavailable.

ToE-mailtheFullTextarticle,clickontheE-mailArticleTexticon.TypeintheE-mail addressandclickon

SendE-mail. (This willnotincludegraphics).

".;

ToDownloadtheFullTextarticle,clickon SaveArticleText. ClickContinue.IntheSaveIn: pull-downmenu

clickonthedriveinwhichyouwanttosaveyourfile(AorC). TypeatitleforyoursearchresultsintheFile

Namebox. ClickSave.(This will notincludegraphics).

Print, Download or E-mail Your Citation Results

Markanycitationsthatyouwishtoprint,downloadorE-mail. Ifyouarelookingatthecitationsthroughthe

TitlesDisplay,clickontheboxtothe leftof thetitle. Whenyoul ~ a v e completedviewingyourcitations, scroll

to theCitationManageratthebottomofthepage..(ITviewingthecitationsin detail, clickon theboxatthetop

of thepage.)

ToPrintthecitationsyouhavemarked,c1ick.'c)ll'theDisplayiconfoundundertheActioncolumn. Thenclick

onthePlinticonfoundonyourWebbrowser. .

ToE-mailthecitationsyouhavemarked, clickontheE-mailiconfound undertheActioncolumn, Typeinthe

E-mailaddressand clickon SendE-mail.

ToDownloadthemarkedcitations,clickontheSaveicon. Inthe"SaveIn:"pull-dowlll11enuclickonthedlive

in whichyouwanttosaveyourfile (AorC). TypeatitlefortheresultsintheFileNamebox. ClickSave.

Note:only200 ofUICsonlinejournalsareavailabledirectlythroughOvid. ConsultUICCATforUIC'sprint

journalholdingsandonlinejoumalholdings(5000+onlinejournals).

ForFurtherAssistance,PleaseSeeReferenceStaff. SDG(07/02)

ComparisonofFunctionalStatusToolsUsedin

Post-AcuteCare

AlanM.Jette,Ph.D.,StephenM.Haley,PhD.,andPengshengNi, M.P.H, M.D.

There is agrowing health policy mandate

for comprehensive monitoring offunctional

outcomes across post-acute care (PAC) set-

tings.This article presents an empirical

comparison of four functional outcome

instruments used in PAC with respect to

their content, breadth of coverage, and

measurement precision. Results illustrate

limitations in the range ofcontent, breadth

ofcoverage, and measurement precision in

each outcome instrument. None appears

well-equipped to meet the challenge ofmon-

itoring quality and functional outcomes

across settings where PAC is provided.

Limitations in existing assessment method-

ology has stimulated the development of

more comprehensive outcome assessment

systems specifically for monitoring the qual-

ity ofservices provided to PAC patients.

INIRODUCl10N

A fundamental barrier to fulfilling the

emerging health policy mandate in the

United States for monitoring the quality

and outcomes of PAC is the absence of

standardized, patient-centered outcome

data that can provide policy officials and

managerswithoutcomedataacrossdiffer-

ent diagnostic categories, over time, and

across different settings where PAC ser-

vicesareprovided(WtIkersonandJohnston,

Theauthorsarewith Boston University. Theresearch inthis

articlewassupporlEdbytheNationa1lnstituteonAgingunder

Grant Number 5P50AGl1669 and the National Institute on

Disability and Rehabilitation Research under Grant Number

HI338990005. Theviewsexpressedinthisarticlearethoseof

theauthorsanddonotnecessarilyreflecttheviews ofBoston

University,tbeNationa1InstituteonAging,theNatiomillnstitute

onDisabilityand RehabHitation,ortheCentersforMedicare&

MedicaidServices.

1997). Recently, the National Committee

on Vital and Health Statistics (NeVHS)

(2002) made recommendations on the

potentialfor standardizing data collection

and reportingfor the purposes of quality

assurance as well as for setting future

researchandhealthpolicyprioritiesinthe

U.S. TheNCVHS (2002)wasunanimousin

stressingtwo majorgoals: "... to putfunc-

tionalstatussolidlyontheradarscreensof

those responsible for health information

policy,andtobeginlaying.thegroundwork

for greater use offunctional status infor-

mationin andbeyondclinicalcare... "The

NCVHS project used the term functional

statusverybroadlytocoverboththeindi-

vidual's ability to carry out activities of

daily living (ADLs) and the individual's

participation in various life situations and

society.

Within PAC, functional outcome instru-

mentshavebeendevelopedandarewidely

usedforvariousapplicationsandforusein

specific settings. Examples include the

functionalindependencemeasure (FJMTM)

foracutemedicalrehabilitation (Guidefor

the Uniform Data Set for Medical

Rehabilitation, 1997; Hamilton, Granger,

andSherwin,1987),theminimumdataset

(MDS) for skilled nursing and subacute

rehabilitation programs (Morris, Murphy,

and Nonemaker, 1995), the Outcome and

Assessment Information Set for Home

Health Care (OASIS) (Shaughnessy,

Crisler,andSchlenker,1997)andtheShort

Form-36 (SF-36) for ambulatory care pro-

grams(WareandKosiniski,2oo1). If one

looks carefully at the content of these

HEALmCARE FlNANCINGREVIEW/Spring 13

instruments, it becomes apparent that sub-

stantial variations exist in item definitions,

scoring, metrics, and content coverage,

resulting in fragmentation in outcome data

available for use across different PAC set-

tings (Haley and Langmuir, 2000).

Differences in conceptual frameworks

used to construct each instrument, the

inability to translate scores from one

instrument to another, and the lack of out-

come coverage and precision to detect

meaningful functional Ghanges across set-

tings, severely limit the field's ability to

measure and analyze recovery through the

period of PAC service provision. If the

PAC field is to achieve the goal of compre-

hensive functional outcome assessment

and quality monitoring for different patient

diagnostic groups across different PAC

settings, efforts are needed to develop

functional outcome assessments that are

applicable across a continuum of post-

acute services and settings.

To our knowledge, no studies exist that

have directly compared the content and

operating characteristics of functional out-

come instruments commonly used in PAC

to examine their relative merits for moni-

toring outcomes across care settings. In

this article, therefore, we report the results

of a direct empirical comparison of the

FIMTM, OASIS, MDS, and the physical

function scale (PF-10) of the SF-36, focus-

ing on three aspects of each: instrument

content, range of coverage, and measure-

ment precision. The objective of this com-

parative analysis is to evaluate the com-

monly held assumption that there exist

fundamental deficiencies in the current

armamentarium of setting-specific out-

come instruments that prevents their

applicability for more comprehensive patient-

centered functional outcome assessment

across diagnoses, over time, and across dif-

ferent settings where PAC is provided. In

response to identified deficiencies in exist-

ing instruments, we also discuss the poten-

tial utility of contemporary measurement

techniques, such as item response theory

(IR1) methods and computerized adaptive

technology (CAl), to yield functional out-

come instruments better suited for out-

come monitoring across PAC settings.

METIlODS

Subjects

These analyses use data from a sample

of 485PAC patients drawn from six health

provider networks in the greater Boston

area. All patients enrolled in the study

were recruited by study coordinators with-

.in their own health care facility and com-

pleted infonned consent prior to participat-

ing in the study. Patients were recruited

from inpatient (199 from acute inpatient

rehabilitation and 90 from transitional care

units); and community settings (90 from

ambulatory services; and 106 from home

care). Eligibility criteria included: (1)

adults, age 18 or over, (2) recipients of

skilled rehabilitation services (physical,

occupational, or speech therapy), and (3)

English speaking. The sample was strati-

fied by impairment group to include

approximately an equal number of subjects

within three major patient groups: (1) 33.2

percent neurological (e.g., stroke, multiple

sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, brain injury,

spinal cord injury, neuropathy); (2) 28.4

percent musculoskeletal (e.g., fractures,

joint replacements, orthopedic surgery,

joint or muscular pain); and (3) 38.4 per-

cent medically complex (e.g., debility

resulting from illness, cardiopulmonary

conditions, or post-surgical recovery). To

assure good representation of levels of

functional severity, the sampling design

was stratified to yield a wide distribution of

subjects representing three distinct severi-

ty levels: slight (35.9 percent), moderate

, ,

HEALTII CARE FINANCING REVIEW/Spring 2003/VOfume24,Nmnber3 14

I

(44.1 percent), and severe (20.0 percent)

based on scores from an adapted modified

Rankin scale (vanSwieten et al., 1988).

The sample reflects the racial and ethnic

distribution of the greater Boston metro-

politan population. The sample contained a

wide age range (19-100 years; mean age =

62.7 years.) The majority of the subjects

were female (58.8 percent), white (81.6

percent), and non-married (61.1 percent).

More than one-half (51.3 percent) had

beyond a high school education. The wide

range of onset from initial injuryI illness

(2.0-3.9 years) characterizes different stages

of recovery within both inpatient and com-

munity settings. The SF-8 Health Survey

(Ware et al., 1999) data indicated that phys-

ical functioning of the overall sample

(mean=40.3, standard deviation (s.d.)=9.9)

was below the D.S. population norms

(mean=50, s.d.=10), although mental func-

tioning (mean=50.2, s.d.=:10.3) was consis-

tent with D.S. population norms (mean=50,

s.d.=10).

Data Collection Procedures

Our overall data collection strategy was

to assess items from existing functional

outcome tools used in PAC so that they

could be combined for analysis into one

common scale. Due to practical data col-

lection considerations and potentially high

patient response burden, we did not admin-

ister items from all four instruments to all

485 subjects. Rather, we linked items

together by administering to the entire

sample a core set of 58 activity items applic-

able for patients in both home and commu-

nity service settings. This method has

been referred to as a common-item test

equating design, in which a core set of

items serve as a scale anchor from which

unbiased parameters can be estimated on

items with missing data (McHorney and

Cohen, 2000).

We collected activity items, when avail-

able, from standardized instruments admin-

istered and recorded in the medical record.

These included the 1B-item FJMTM for per-

sons in inpatient rehabilitation settings

(N=108), 19 MDS items (physical function-

ing and selected cognitive items) for per-

sons in skilled nursing home settings

(N=91), and 19 ADL/individualADL items

from the OASIS or persons receiving home

care (N=103). Since there were no consis-

tent data available from charts in the out-

patient setting, we administered the 10

physical functioning items of the SF-36 to

individuals receiving outpatient services

(N=82).

We applied specific rules for handling

missing item data within two of the stan-

dardized instruments. In accordance with

FIMTM scoring rules, items that were not

administered are scored as "total depen-

dence." The MDS items have a response

option of "activity did not occur." 'We con-

verted these codes to the lowest score for

that item, namely "total dependence." We

reasoned that the most likely explanation

for the activity not occurring was that the

item could not be performed, an assump-

tion that others have made when compar-

ing functional instruments. (Buchanan et

al., 2002). Missing data for the PF-I0 and

OASIS were not systematically recoded.

The 58 core activity items collected on all

485 subjects were used as scale anchors. In

order to compare items from instruments ,

across PAC settings, a common link was

needed to provide a stable functional base

for comparison purposes. The common-

item test equating design was used so that

every subject had a similar core set of

items. Rasch (1980) models (Wright and

Masters, 1982) can be conducted with miss-

ing data if a core set of items is used to link

the setting-specific instruments into a

common scale. Core items included: 15

physical functioning, 14 self-care, 12 daily

HEALm CARE FINANCING REVIEW/Spring 2003/"'lume 24, Number 3 15

routine, 11 communication, and 6 interper-

sonal interaction items. Activity questions

asked, "How much difficulty do you cur-

rently have (without help from another per-

son or device) with the following activi-

ties...?" A polytomous response choice

included "not at all," "a little," "somewhat,"

"a 101," and "can not do." We framed the

activity questions in a general fashion with-

out specific attribution to health, medical

conditions, or disabling factors. For some

individuals in the community settings, we

also collected 52 additional functional items

(N==I96) and added those to the common

linking solution, however the results of

these items are not reported here. None of

the subjects had difficulty in completing the

core set of 58 items.

Data on items from three of the existing

instruments (e.g., FIMTM. OASIS. and

MDS) were recorded from retrospective

chart review. Data on the PF-I0 items (out-

patient programs) and core and communi-

ty items were collected via subject or proxy

interviews. Each interview (approximate-

ly 45-60 minutes) was conducted in a quiet

atmosphere in an inpatient setting. an out-

patient facility. or participanfs home. The

ability of a subject to take part in the inter-

view self-report was assessed by a treating

clinician who determined if the respondent

could: (1) understand the interview ques-

. tions, (2) sustain attention during an inter-

view, and (3) reliably respond to the ques-

tions. If the answer to any of these screen-

ing questions was no, then the interview

was completed by either a clinician or fam-

ily member proxy participant A proxy par-

ticipant completed less than 3 percent of

the interviews.

Interviews that included information on

core items were timed to coincide with

administration of standard outcome instru-

ments. For example. FIMTM is adminis-

tered in most facilities within 3 days of

admission and prior to discharge in the

inpatient rehabilitation setting. Thus, the

subject interview was arranged to take

place within 3 days of admission or dis-

charge such that FIMTM information was

collected close to the time of the interview.

likewise, interviews of subjects in transi-

tional care units were scheduled to coin-

cide with the MDS assessment Subjects

receiving home care therapy were inter-

, viewed either near to admission or dis-

charge such that the OASIS assessment

was performed in close proximity to the

subject interview. The interview was fully

scripted. with standard instructions and an

answer card to help subjects identify the

desired response choice. The order of pre-

sentation of test sections was randomly

assigned to mitigate the possibility of large

portions of missing data in anyone section

due to respondent fatigue.

Interviewers. who were experienced

rehabilitation clinicians (mean years of

clinical experience==5.7 years). received

training and quality assurance from: (1) an

initial 3-hour training session. (2) a proto-

col manual, (3) supervision by the research

project staff on all first interviews. and (4)

acceptable completion of a procedural

checklist and inter-rater reliability on a

subsequent interview. A project staff mem-

ber accompanied interviewers on approxi-

mately every 10th interview to check on

adherence to study protocol and to assure

overall quality control. All subjects.

regardless of setting, were administered

the SF-8 items to establish a normative

description of the sample.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted in three

stages. First, we conducted one-parameter

Rasch (1980) partial credit analyses for the

entire item pool (instruments and

core!community items) to develop an

overall functional ability scale (Wright and

HEAL1H CARE FINANCING ~ p r l n g 2003/VoIume24,Number3 16

Masters, 1982). The Rasch partial credit

model allows for different number of

response categories across items. For

example, the FIMTM scale has a seven-point

rating scale, while the OASIS incorporates

multiple response categories that differ per

item. This overall scale was used to esti-

mate parameters for all items in each of the

four comparison instruments. We used a

method of concurrent calibration, which

involves estimating item and ability para-

meters in the, overall subject and item pool

simultaneously. This treats items not

taken by subjects as missing, as the Rasch

program uses information available to esti-

mate person and item parameters. Our

goal was to develop a general scale for

functional abilities, and specifically to see

the location of item content across the four

existing instruments. We calculated inter-

nal consistency estimates-Cronbach

alpha (1951)-for each of the individual

instruments and for the overall functional

scale to determine the levels of consisten-

cy of the items within the overall function-

al scale. We also calculated goodness of fit

tests for all items with the overall function-

al scale using the standardized infit statis-

tic (+/-2.0) to determine the number of

items with poor fit within the overall scale.

Second, we examined the relative

amount and range of activity content cov-

ered by each of the four existing instru-

ments and made comparisons across

instruments. To do this, we used the

extreme (highest and lowest) item thresh-

old estimate for each instrument A

threshold represents the point of separa-

tion between adjacent item response cate-

gories for each item. The Rasch partial

credit model estimates thresholds for each

item, and the minimum and maximum

threshold values per instrument were used

to establish the range of content within the

overall functional ability scale.

Third, we calculated item and test infor-

mation functions (Lord, 1980; Dodd and

Koch, 1987; Murnki, 1993) to estimate the

location of optimal measurement precision

of each instrument The item information

function is an index of the degree and loca-

tion of information that a particular func-

tional item provides for estimating a score

along a functional ability scale. Item infor-

mation functions are related to the location

and shape of the item characteristic curve

(lCC), which describe the probabilities of

responding to particular response options

of an item. The steeper the slope of the

ICC, the more information about function-

al ability provided by an item in the scale,

thus the greater level of item discrimina-

tion and precision associated with esti-

mates of the score at that point along the

scale. ICCs that have a broad range of cov-

erage along the scale provide information

functions across a wide range of the scale.

Therefore, the information function is the

relationship of the amount of information

of an item at a particular scale level and is

described by the ratio of the slope of the

ICC and the expected measurement error.

Test information functions were calculated

by summing the item information func-

tions to obtain an estimate of the measure-

ment precision of the entire test at differ-

ent levels of the functional ability continu-

um. We compared the test information

function with the ability levels of the sam-

ple in each major setting (inpatient, com-

munity). We calculated a summary score

converted to 0-100 metric for each person

based on the overall item pool.

RESULTS

The internal consistency values of the

four functional ability instruments were as

follows: MDS=O.97, OASIS=0.99, FJMfM-

0.99. and the PF-10=0.99. The internal

HEALm CARE FINANCING REVIEW/Spring 2003/VoIutne 24. Number 3 17

Figure1

RaschModelComparisonof the FourPost-AcuteCareInstruments

. FIM 1-1--/------+---/------+---/-----1----1---+----1,------1

PF-10I

I 1.#

e

::11

i

.. /' ~

~

/' V /'\

MOO I

I I

/0

it'/

qf

OASISI

I

20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70

,.

ItemScale

Less Ability MoreAbility

Functional Ability

NOTES:LocationsarederMI<fasestimatesofthe 8'Yerageitemdilficullyparametergeneratedfor eachinsIntment. FIM1M is

functionalindependentmeasum.PF-10isphysicalfunctionindex(10items). !lADSis minimumdataset. OASISis

StandardizedOutcomeandAssessmentInfDrmalionSetforHomeHeahh.UEisupperexfmmily.LEislowerextremity.

SOURCES:(Hamilton,Granger,andSherwin,1987;Morris, Murphy,andNonemaker,1995;wamandKosinski,2001;

Shaughnessy,Ctisler,andSchIenker,1997.)

consistency of the items within the full

functional ability scale was O ~ 8 5 Only five

of the items within the existing instru-

ments (7.2 percent) exceeded the good-

ness of :6t values. Thus. we felt it was

acceptable to combine the items from each

of the four functional outcome instruments

into an overall functional ability scale for

the purposes of directly comparing their

range of functional content, breadth of cov-

erage, and measurement precision.

FIgUre 1 illustrates and compares the

location of items in each of the four func-

tional outcome instruments along the

broad content dimension of functional abil-

ity. These locations are derived as esti-

mates of the average functional ability para-

meter generated for items in each instru-

ment included inthe analysis. Across all

four instruments it can be seen that cogni-

tive, communication, and bowel and blad-

der continence function items achieved the

lowest functional ability estimates, indicat-

ing that those items were usually less diffi-

cult for persons inthe sample to perform

compared with other items contained in

these instruments. Ingeneral, the PF-IO

scale contained items with the highest item

REALmCAREFtNANCINGREVIEW/SpriDg2003/VolumeU. Nlllllher3 18

Figure2

ComparisonofActualRangesCoveredbytheFourPost-AcuteCareInstruments

100

99

MDS OASIS

FIMTM PF-10

Instrument

NOTES: Content coverage is calculated by the high and low step estimates for each item's response cate-

gory. MDS is minimum data set. OASIS is Standardized Outcome and Assessment Information Set for

Home Health. FIMTM is functional independent measure. PF-10 is physical function index (10 items).

SOURCES: (Hamilton, Granger, and Sherwin, 1987; Morris, Murphy, and Nonemaker, 1995; Ware and

Kosinski, 2001; Shaughnessy, Crisler, and Schlenker, 1997.)

100

90

80

70

60

C

III

50 u

..

l.

40

30

20

10

0

0 0.5

86

25

50

functional ability calibrations compared

with the other three. A substantial number

of items in the FIMTM, OASIS, and MDS

instruments achieved average functional

ability calibrations in the mid-point of the

functional ability continuum. Figure 1 also

reveals the substantial overlap of item con-

tent across these four instruments.

The actual range of functional ability that

is covered by the items contained in each of

the four functional outcome instruments is

presented in Figure 2. The content cover-

age is calculated by the high and low step

estimates for each item's response cate-

gories instead of average estimates, which

were the basis of the information presented

in Figure 1. Consistent with the general

spread of the functional ability parameters

illustrated in Figure 1, the range of cover-

age shown in Figure 2 appears greatest for

both the MDS and the OASIS instruments

as compared with either the FIMTM or PF-10

scales. Because of the high step estimate

for one of the transportation items in the

OASIS, the actual range of coverage of the

OASIS is nearly the entire range of all four

instruments.

Figure 3 displays the measurement pre-

cision of each instrument as depicted by

the test information function curves.

These curves are superimposed with the

average score on the functional ability con-

tinuum and 2 standard deviation for the

inpatients and community samples. Note

the location of the peak amount of preci-

sion for each instrument in relationship to

HEALTH CARE FINANCING REVIEW/Spring 2003/Volume 24, Number 3 19

Figure3

MeasurementPrecisionofPost-AcuteCareInstruments,byTest

27

22

c

0

17

:a

0

c

:::s

IL

c

12

0

:;

E

..

i

7

2

-3

,

,

,

.

,

.

,

.

...... \"

-- PF10items

. FIMTM items

--- OASISitems

-.MOSitems

inpatients

- ...- Outpatients

..'

,...

..

.......

, .

'\ .......

-..

...

Inpatients

Outpatients

60 70 80 20 30 40 50

FunctionalAbility

NOTES:CurvesaresuperimposedwiththeaveragescoreonthefunctionalcontimJum and 2standarddeviation

for inpatientsandcommunitysamples. MDSIsminimumdataset.OASISisStandaldi2:edOutcomeand

AssessmentInformationSetforHomeHealIh. FIMT"isfundionallndependentmeasure. PF-10isphysicalfunction

index(10 items).

SOURCES:(Hamilton,Granger,andSherwln,1987;Morris, Murphy,andNonemaker,1995;WareandKosinskl,

2001;Shaughnessy,CrisIsr,andSchIenker.1997.)

each sample. Although the OASIS items

contain a broad range ofcontent, as was

seeninFigure2, theOASISitemsprovide

ahighdegreeofmeasurementprecisionat

onlytheverylowendofthefunctionalabil-

ity dimension for both the inpatient and

community samples. The precision of

MDS items is also greatest at the lower

functional ability dimension levels,

although the MDS items have a greater

spanoffunctionalabilityinwhichtheypro-

vide some levels ofprecision. The FIMTM

itemspeakatthelowto moderateendof

theinpatientsample. Incontrast,theinfor-

mationfunctionofthePF-IOitemspeaksat

thehighendofthecommunityoutpatient

sample with very poor precision for the

inpatientsample.

DISCUSSION

Theresults oftheseanalyses ofinstru-

mentcontent,coverage,andmeasurement

precision provide directevidence ofwhat

many have argued are the major limita-

tionsofexistingfunctionaloutcomeinstru-

mentscurrentlyinusewithinPAC. While

eachofthefourinstrumentscomparedin

thisanalysisappearswellsuitedforitspri-

mary application, none of them appears

well-equipped for thecurrentpolicy man-

date for monitoring the quality and out-

come of PAC provided over time and

acrossdifferentPACsettings.

IfonelooksattheresultsfortheFJM1'M,

themostwidely used outcome instrument

in PAC, one cansee thattheFIMTM items

HEALmCAREFINANCINGREVIEW/Spring2003/Vo1ume24,Number3 20

cover a very small portion of the functional

ability continuum within a narrow range of

functional content The flMTM is most pre-

cise and relevant for PAC inpatients whose

function is at the low end of the continuum.

All of these characteristics of the FIMTM are

acceptable when one considers its primary

application is for evaluation of inpatient

rehabilitation services. These FfMTM char-

acteristics become severe limitations, how-

ever, if the intended application is assess-

ment of outcomes or quality across PAC set-

tings. An instrument such as the PF-10 suf-

fers from a similar type of limitation, as does

the FIMTM. The PF-10 covers a narrow

range of functional content, although, unlike

the FIMTM, the content covered by the PF-10

is at the higher end of the functional activity

continuum. The PF-10 appears most pre-

cise for community dwelling outpatients,

but much less so for inpatients such as

those seen in many rehabilitation facilities.

When used with high functioning communi-

ty patients, the PF-10 covers appropriate

content; its content and range is severely

limited in application to patients within insti-

tutions. The MDS and OASIS instruments,

in comparison with the FIMTM and PF-lO,

cover content from the mid portion of the

functional ability continuum with less con-

tent covering the low or high ends. Patients

functioning at the very high or very low.end

of the functional continuum would not be as

well served by the OASIS and MDS.

Concerns about existing instruments

used in PAC, such as the four examined in

this analysis, have stimulated the develop-

ment of more comprehensive functional

outcome instruments developed specifical-

ly for application across diagnostic groups,

and across PAC settings. An example of

this type of work is found in the activity

measure for PAC (AM-PAC), developed by

the Rehabilitation Research & Training

Center for Outcomes based at Boston

University (Haley and Jette, 2000). In con-

structing the AM-PAC, its developers used

the strategy of combining functional ability

items found in existing instruments and

from a variety of other sources into quanti-

tative scales that can be employed to

assess a wide range of functional content

needed to assess quality and outcomes of

patients seen across PAC settings.

Although instruments such as the AM-

PAC are promising, the continued use of

traditional, fixed-form measurement method-

ology for constructing' functional outcome

instruments presents the researcher with

two common problems that limit their utility

in clinical outcomes assessment One fun-

damental problem encountered with fixed-

form instruments of modest length is floor

and ceiling effects where large numbers of

individuals who complete these outcome

instruments score at either the top or the

bottom of the range of possible scores.

These ceiling and floor effects severely

reduce measurement precision and thus,

restrict the utility of the instruments

(Andresen et al., 1999; Brunet et al., 1996;

DiFabio et al., 1997; Rubenstein et al.,

1998). In response to concerns over inade-

quate measurement precision and inade-

quate coverage of important outcome

domains, some researchers develop more

comprehensive and lengthy outcome instru-

ments. Lengthy instruments lead to the

frustration and fatigue faced by many sub-

jects and busy clinicians overwhelmed by

large and burdensome batteries of instru-

ments (Meyers, 1999).

One promising solution offered to mea-

surement problems faced by traditional

fixed form instruments is offered through

the combined application of IRT methodol-

ogy and CAT techniques (Ware et al., 1999;

Ware, Bjorner, and Kosinski, 2000; Weiss"

1982; Hambleton, 2000). These techniques

of test construction are currently being

applied to the development of a new gener-

ation of functional assessment instruments

REALm CARE FINANCING REVIEW/Spring 2003/V01ume24, Number" 3 21

designed for use in PAC settings (Haley

and Jette, 2000). CAT methodology uses a

computer interface for the patient (or a

computerized interview/clinician report)

that is tailored to the unique functional abiJ...

ity level of the patient. The basic notion of

an adapted test is to mimic what an experi-

enced clinician would do. A clinician

learns most when he/she directs ques-

tions at the patienfs approximate level of

proficiency. Administering outcome items

that are either too easy or too hard pro-

vides little information. An adaptive test

first asks questions in the middle of the

ability range, and then directs questions to

the level based on the patienfs responses,

without asking unnecessary questions.

This allows for fewer items to be adminis-

tered while gaining precise information

regarding an individual's placement along

a continuum of functional ability. CAT

applications require a large set of items in

anyone functional area (item pools), items

that consistently scale along a dimension of

low to high functional ability, and rules

guiding starting, stopping, and scoring

procedures. Large item sets such as the

AM-PAC can be readily adapted to a CAT

format in future work.

Methods like IRT that make it possible

to calibrate questionnaire items on a stan-

dard metric (ruler) also yield the algo-

rithms necessary to run the engine that

powers CAT assessments. These statisti-

'cal models estimate how likely a person at

each level of function is to choose each

response to each survey question. This

logic is reversed to estimate the probabili-

ty of each health score from a particular

pattern of item responses. The resulting

likelihood function makes it possible to

estimate each person's score, along with a

person-specific confidence interval. In

principle, one can derive an unbiased esti-

mate of an outcome, i.e., an estimate with-

out systematic error, from any subset of

items that fits the model. The number of

items administered can be increased to

achieve the desired level of precision. Most

statistical models for estimating such item

parameters can be traced to the work of

Rasch (1980) or on a second tradition-

IRT (Hambleton and Swaminathan, 1985).

Both models assume unidimensionality;

i.e., that the items included on a particular

scale measure only one concept. Whether

these techniques, if applied to functional

outcome assessment, will solve the prob-

lems presented by traditional, fixed form

methodology, needs to be carefully evalu-

ated in future research.

There are several limitations in the

analyses reprinted in this article. To

achieve a direct comparison of these four

instruments, we used a liberal interpreta-

tion of unidimensionality to combine items

from all of the four comparison instru-

mentS into a single scale. This simplified

the presentation so that an instrument-

based rather than a content-based compar-

ison could be made. A more detailed

examination of common functional dimen-

sions that underlie the item set was beyond

the scope of this article. We also point out

that, for practical reasons, we combined

data from medical records and from inter-

views to develop the item calibrations for

the instrument comparisons. Although not

ideal, we do find only small amounts of

error from clinician and self-report inter-

view modes of testing within these func-

tional items (Andres, Haley, and Ni,

Forthcoming). More work in this area of

combining data across respondents and

modes of data collection will be needed as

the field advances in assessing functional

ability across post-acute core settings.

HEALm CARE FINANCING REVIEW/Spring 2003h>1mne24, Number 3 22

CONCWSION

Results of this analysis illustrate some of

the inherent limitations in the range of con-

tent, breadth of coverage, and measure-

ment precision found in functional outcome

instruments currently in use within PAC.

Umitations in existing functional outcome

methodology has stimulated the ongoing

development of more comprehensive out-

come assessment systems specifically for

monitoring the quality of services provided

for patients with dif:ferent across diagnoses

and across PAC settings. The careful use of

IRT-based measurement methods coupled

with CAT outcome assessment techniques

may hold future promise for making out-

comes assessment brief er and less burden-

some to patients, and thus more acceptable

for use in busy clinical settings. What is

needed is functional outcome data that is

applicable to patients treated across differ-

ent clinical settings and applications, more

efficient and less costly to administer, and,

sufficiently precise to detect clinically

meaningful changes in functional outcomes.

Contemporary measurement methodology

may hold considerable promise as a vehicle

for advancing PAC outcomes evaluation,

thus avoiding the pitfalls of traditional

assessment methodology.

REFERENCES

Andres, P.L, Haley, S.M., and Ni, P.S.: Is Patient-

Reported Function Reliable for Monitoring Post-

Acute Outcomes? American Journal 0/ Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation. Forthcoming.

Andresen, E.M., Gravitt, G.WJ., Aydelotte MR, et

al.: limitations of the SF-36 in a Sample of Nursing

Home Residents. Age and Aging 28:562-566, 1999.

Brunet, D.G., Hopman, W.M., Singer, M.A, et al.:

Measurement of Health-Related Quality of Life in

Mu1tiple Sclerosis Patients. Canadian Journal 0/

Neurological Sciences 23:99-103, 1996.

Buchanan, ]., Andres, P., Haley, S., et al.: Final

Report on the Assessment Instrument /br PPS, MR-

1501-CMS. RAND. Santa Monica. CA 2002.

Cronbach, L: Coefficient Alpha and the Internal

Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 16(3):297-334.

1951.

DiFabio, R.P., Cboi, T., Soderberg, J., et al.: Health-

Related Quality ofIife for Patients with Progressive

Multiple Sclerosis: Influence of Rehabilitation.

Physical Therapy 77:1704-1716, 1997.

Dodd, B., and Koch, w.: Effects of Variations in

Item Step Values on Item and Test Information in

the Partial Credit Model. Applied Psychological

Measurement 11:371-384, 1987.

Guide for the Uniform Data Set for Medical

Rehabilitation, (lncluding the FJMIM Instrument,

Vemon 5.1.) State University of New York at

Buffalo. Buffalo, NY. 1997.

Haley, S., and Jette, A: Extending the Frontier of

Rehabilitation Outcome Measurement and

Research. Journal 0/ Rehabilitation Outcome

Measurement 4(4): 31-41, 2000.

Haley, S.M., and Langmuir, L: How Do Current

Post-Acute Functional Assessments Compare With

the Activity Dimensions of the International Oassi-

fication of Functioning and Disability aCIDH-2)?

Journal 0/ Rehabilitation Outcome Measurement

4(4):51-56,2000.

Hambleton, R.: Emergence of Item Response

Modeling in Instrument Development and Data

Analysis. Medical Care 38(9 Supplement m; II60-

1165,2000.

Hambleton, R and Swaminathan, H.: Item Response

Theory: Principles and Applications. Kluwer Nijhoff.

. Boston, MA 1985.

Hamilton, B., Granger, C., and Sherwin, F.: A

Uniform National Data System for Medical

Rehabilitation. In Fuhrer, M. (Ed.) Rehabilitation

Outcomes: Analysis and Measurement. Paul H.

Brooks. Baltimore, MD. 1987.

Lord, F.: Applications 0/ Item Response Theory to