Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Project111 smcc144

Încărcat de

burvanovDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Project111 smcc144

Încărcat de

burvanovDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

THE ELECTRO-MECHANICAL DESIGN OF RIGID AND STRAIN BUSBAR SYSTEMS

Shaun M. McCarthy

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

This work has been commissioned by Sinclair Knight

Merz to investigate the processes involved with rigid

busbar system (RBS) and strain busbar system (SBS)

design. This paper deals with the theory behind the

various forces exerted upon these busbar structures and

their corresponding electro-mechanical responses. A

novel method for calculating the final tension due to

temperature change in an aerial conductor and an outline

for modelling concentrated masses on RBS conductors

is presented. To illustrate the processes involved, a

design demonstration comparing RBS and SBS is

conducted. A cost analysis is performed, revealing that

the RBS is the more economical of the two designs.

1. Introduction

Busbar systems are structures within substations that

serve as connections between electric circuits of a power

system and consist of conductors, insulators, supports

and associated connections. These structures account for

a large percentage of the overall substation equipment

investment [1]. Proper design is essential for safe,

reliable and economic operation of the power system.

Of the existing substations today, air insulated

substations (AIS) account for the majority [2]. There are

two main busbar construction types used in AIS designs.

These are rigid busbar systems (RBS), utilising tubular

conductors (Figure 1.1) and strain busbar systems

(SBS), utilising hanging aerial conductors (Figure 1.2).

Regarding RBS, aluminium alloys are commonly used

for the tubular conductors [1][3], which are typically

Figure 1.1: Example of a rigid busbar system [4].

Figure 1.2: Example of a strain busbar system

(adapted from [5]).

connected to vertically arranged porcelain insulators and

steel supports [2]. Selection of the tube dimensions is

frequently governed by mechanical strength

considerations rather than electrical requirements [1].

With respect to SBS, the conductor is usually all

aluminium conductor (AAC) for short spans, and

aluminium conductor steel reinforced (ACSR) for

longer spans [2]. The aerial conductors are attached to

insulator strings (as opposed to vertical insulators for

RBS), which in turn are also connected to steel support

structures. The common case of three phases, arranged

in a horizontal plane, is considered in this paper.

A distinct advantage of RBS is their low and

compact physical profiles, which allow for less required

substation area and more pleasing aesthetics. The

disadvantages lie in the fact that the rigid conductors

and insulators are more susceptible to damage caused by

earthquakes, and more support structures are needed due

to span limitations. The advantages of SBS design are

increased ability to handle earthquake loads and greater

allowable spans, resulting in less number of support

structures required. A disadvantage is the need for large

clearances due to the ability of the conductors to move,

requiring a greater investment in substation ground area.

It is the goal of this paper to present an investigation

into the types of forces these busbar systems are

exposed to during their operational lives, describing the

very different electro-mechanical responses of RBS and

SBS separately. This work has been commissioned by

Sinclair Knight Merz (SKM) to develop a better

understanding of the phenomena involved in the design

of RBS and SBS. Other objectives of this work have

included the development of calculation sheets for each

RBS and SBS, and the application of the sheets to a

theoretical scenario, with the purpose of demonstrating

the design process. It has been decided to base the

calculation sheets on the standards of the New Zealand

system operator, Transpower, particularly [3], which

closely follows IEEE standard 605 [1]. Many of the

results and figures presented in this paper have been

created using the developed calculation sheets.

This paper is structured in the following manner.

Section two describes the gravitational and climate

dependent loads that are incident upon the systems and a

novel method for calculating temperature induced sag

increase of a strain conductor is outlined. Section three

is dedicated entirely to short-circuit forces, which is

considered the most critical factor in busbar design.

Section four describes the electro-mechanical response

of a rigid tubular conductor and section five discusses

other design issues including insulator selection,

vibration and topics for further development of this

work. Section six contains a design demonstration to

bring together the presented theory. A cost analysis

comparing RBS and SBS is performed. The paper

culminates in section seven with conclusions.

2. Gravitational and climatic loads

2.1. Dead weight and concentrated masses

A rigid conductor must be designed to withstand the

loads created by the conductors own weight, referred to

as dead weight, and any concentrated masses along the

span, due to, for example, connections down to other

pieces of equipment. In response to these gravitational

loads, the conductor vertically deforms. Vertical

deflection of the rigid conductor is treated in detail in

section four. Th e to the conductor

dead w ght, F

c

( /

e force per metre du

N m), is

F

c

= nw

c

(

o

-t

c

) (2.1)

ei

t

c

where w

c

is the specific conductor weight, being 26,700

N/m for aluminium [6], t

c

is the conductor tube wall

thickness (m) and

o

is the conductor outer diameter

(m). The effect of concentrated masses on deflection

requires more complicated treatment and is also

discussed in section four.

In 1691, mathematicians J akob Bernoulli, Christiaan

Huygens and Gottfried Liebniz each proved separately

that the shape assumed by a string hung freely from two

points is the catenary (Figure 2.1), which is

mathematically described by the hyperbolic cosine

function [7]. A strain conductor hangs as a catenary

under dead weight [8][9]. The sag of the strain

conductor is defined as the vertical distance from the

lowest hanging point of the conductor to the imaginary

horizontal line connecting the two attachment points

(Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: The catenary curve (adapted from [8]).

In situations where the sag of the conductor is smaller

than one eighth of the span length, a parabolic

approximation of the catenary may be used for

calculating the sag [1][ or same-levelled attachment

points, this appears as

8]. F

=

mgL

2

8H

(2.2)

where is the conductor sag (m), m is the conductor

unit mass (kg/m), g is the gravitational constant (9.81

m/s), I is the span length (m) and E is the horizontal

component of the tension inside the conductor (N). It is

common practise to refer to conductor tensions as

percentages of calculated breaking strength (%CBL) [8].

Strain conductors are usually installed with an initial

tension of low value, less than 10%CBL [2].

An example provided in [8] shows that for a 300m

transmission line, the sag calculated by the catenary

equation and the parabolic approximation is 6.420m and

6.417m respectively, yielding a difference of only 3mm.

2.2. Wind loads

The strength of forces caused by wind is subject to the

location of the busbar system. The wind is assumed to

act on the structure in the horizontal direction, as this

causes the maximum force [1]. The New Zealand

loadings d ves t sp ed, I

z

(m/s),

from the r wing

co e [10] deri the si e wind e

egional w d speed, I (m/s), as follo

I

z

= IH

I (z,cut s

H

t

H

K

sh

K

u

(2.3)

in

s

H

)

H

where the various H and K factors account for the site

terrain and elevation, height of the structure, the

possible effect of wind reduction provided by

neighbouring buildings and so f h. ort

The wind force ,

w

(N/m), acting on the

nductor is given b

per metre F

y

F

w

= C

d

o

q

z

. (2.4)

co

C

d

is the drag-force coefficient, which describes how

wind flows around different shapes and is equal to 1.2

for a circular cross-section [10], as is the case for both

RBS and SBS conduct rs e conductor diameter

(m) and q

z

is the desig ure (Pa) given by

o .

o

is th

n wind press

q

z

= u.6I

z

2

. (2.5)

The 0.6 value comes from half times the density of air,

measured in kg/m.

2.3. Ice loads

Ice loading is clearly only applicable to regions

susceptible to ice formation. The ice build-up is

assumed to form around the conductor uniformly

[1][3][10]. The force by the weight of

ice around the cond ven by

per metre caused

uctor, F

(N/m), is gi

F

= nw

(

o

+ ) (2.6) r

where w

is the specific ice weight (N/m), r

is the

uniform ice radial thickness (m) and

o

is the conductor

diameter (m). As an example, [3] specifies w

and r

to

be 3924 N/m and 3 cm respectively. Transpower

defines the complete load due to ice to be the vertical

force caused by the weight of the ice, coupled with the

horizontal force due to wind acting upon the augmented

section of ice [3]. In this case, the wind speed used in

(2.5) is equal to 0.9 times that of the wind speed used to

calculate the wind load when ice is absent [10].

The presence of ice on the strain conductor causes an

increase in tension [11] that can be conservatively

calculated using methods in [1].

2.4. Thermal considerations

A rigid tubular conductor responds to an increase in

temperature by elon t T ange in length, I

(m), is described by

gaing [1]. he ch

I = oI(I

]

-I

) (2.7)

where o is the coefficient of thermal expansion of the

conductor (1/C), equal to 23.1E-06 1/C for aluminium

[1], I is the length of the conductor (m), I

]

is the final

temperature (C) and I

is the initial temperature (C).

The resulting e ng ermal expansion

force o e con

1L

(N):

lo ation causes a th

ductor and insulators, F

F

1L

= E

c

A

c

o(I

]

-I

) (2.8)

n th

where E

c

is the Youngs modulus (Pa) and describes the

stiffness of the conductor material. It is equal to 68.9

GPa for aluminium [1]. A

c

is the cross-sectional area of

the conductor (m). Thermal expansion puts excessive

stress on the conductor and cantilever (bending) forces

on the insulators. One solution is to install a sliding joint

at one end of the RBS span to accommodate the

expansion [1][3]. The presence of a sliding joint affects

1) the vertical deflection of the conductor, 2) the

maximum stress occurring on the cross-section, 3) the

conductors natural frequency and 4) the transmittance

of loads to the insulators. These effects will be discussed

at relevant points in later sections of the paper.

The response of a strain busbar conductor to an

increase in temperature, is an increase in sag [1][8][11].

As temperature rises, the conductor elongates and the

tension within decreases [11]. The general change-of-

state equation that describes this phenomenon is as

follows.

E

c

+ E

=

g

2

L

2

L

c

A

c

24

c

A oI E

]

- _

m

]

2

H

]

2

-

m

i

2

H

i

2

] (2.9)

where I = (I

]

-I

) (C), E

]

is the final tension (N),

E

is the initial/installation tension (N), m

]

is the final

unit mass (kg/m) and m

is the inital/installation unit

mass (kg/m), with all other parameters mentioned

previously. It is noted that the only variable in (2.9) is

E

]

. By solving for E

]

, the final sag can be calculated

using (2.2). Figure 2.2 shows the initial sag at a

temperature of 15C and the final sag at a temperature of

80C for a SBS with a 32m span length.

Figure 2.2: Sags associated with a 32m span length.

Sag and tension calculations are of high importance in

SBS design to ensure that the minimum phase-to-ground

clearance is not violated (Figure 2.2), which if occurs,

can result in the dangerous conditions of electrical

arcing.

Equation 2.9 is non-linear and is traditionally solved

using iterative techniques like the Newton-Raphson

method, details of which can be found in [12] or any

introductory text on calculus. This prohibits the

convenience that comes with step-by-step progressive

calculation. During the project, the author has developed

a novel method for accurately solving (2.9). This

involves two separate approximation methods that allow

direct calculation of E

]

. To demonstrate the accuracy of

the approximations (in this case, the quadratic error

method (QEM) approximation), Figure 2.3 shows the

deviation between true sag and approximated sag across

different cross-sectional areas for AAC material. The

different curves correspond to the cases outlined in

Figure 2.3: QEM sag deviations [13].

Table 2.1. The details of these methods can be found in

[13] and a brief summary is provided in the appendix.

Table 2.1: Theoretical case definitions [13].

Case

I (m) 50 150 50 150

I (C) 50 50 100 100

3. Short-circuit forces

Mechanical stresses are especially severe during short-

circuit conditions [14] and so are treated very seriously

in the design of busbar systems. Short-circuit forces

may cause substation failure, particularly due to the

failure of insulators [2], and are the dominant influence

in substation design [15]. The mechanical effects of

short-circuit currents for RBS and SBS are quite

different [2]. This section shall begin by discussing the

underlying theory behind short-circuit forces, followed

by the effects on RBS and SBS respectively. In the

following discussion, the terms short-circuit and fault

are used interchangeably.

When two or more current carrying conductors are

in close proximity, they exert electromagnetic forces

upon one another. The direction of the forces is

repulsive if the currents flow in opposite directions, and

attractive if the currents flow in the same direction [16].

Under fault conditions, the currents within the

conductors can become excessive, and the forces

exerted on the conductors become significant since they

are proportional to the square of the fault current (as

shall be made clear soon). Fault currents consist of an

asymmetric decaying component and an oscillating

symmetrical steady-state component (Figure 3.1). The

instantaneous value of the fault current is affected by the

impedances in the adjacent power system (especially the

synchronous machine reactances), the system reactance-

to-resistance ratio (determines how quickly the

asymmetrical component decays [17]) and the timing of

the fault with respect to the system frequency [18]. The

current may reach a maximum of nearly double the

steady-state value [19].

Figure 3.1: Fault current waveform [20].

The physical laws that relate the current in the

conductors to the electromagnetic forces they create are

1) the Biot-Savart law, which is used to find the

magnetic field caused by the current, and 2) Laplaces

law, which determines the force created by the magnetic

field [16].

For parallel conductors, such as the RBS tubes, the

equation for the electrom netic force per metre, F

SC

(N/m), can be derived

ag

as

F

SC

=

1.6kI

SC

2

d

(3.1 )

where I

SC

is the symmetrical RMS fault current (kA), J

is the conductor spacing (m) and k is a corrective factor

which takes into account 1) the type of fault current, 2)

the conductor location (i.e. middle phase or outer

phase), 3) the peak current decay and 4) the mounting

structure flexibility [1]. In deriving (3.1), it is assumed

that since the conductor length is much larger than the

spacing, d, it can be regarded as being of infinite length

[16][21]. Three phase symmetrical faults create the

highest mechanical forces [16][21][22] and so the

current associated with this type of fault is usually

specified for I

SC

in the design.

The assessment of short-circuit forces in SBS is a

problem of higher complexity than for RBS [2][23].

Significant mechanical stresses and deflections occur in

the SBS [2][9][24] and the associated calculations

exceed three dozen equations. For the sake of brevity,

only a descriptive treatment will be provided for the

short-circuit forces associated with SBS. Full details of

the calculations can be found in the IEC standard [25]

and the CIGRE guide to this standard [2]. The SBS

response can be analysed in terms of three phenomena

[26], which will now be discussed in order of their

occurrence.

The first phenomenon is known as the pinch effect

and results from the collapse of subconductors in a

bundle due to the attractive electromagnetic forces

caused by the short-circuit current [2][15][23][24].

Bundles are often used in applications with high load

current requirements where one conductor is not

sufficient. Figure 3.2 shows the pinch effect occurring

for a bundle of three subconductors. One can see that

the bundle has fully collapsed a mere 18ms after the

initiation of the short-circuit event. This is small in

relation to the typical duration of a short-circuit, which

is 15 cycles [15], corresponding to 300ms for a 50Hz

system.

Figure 3.2: The pinch effect [23].

The increase in length of the subconductors as they are

bent inward results in an increase in tension [15].

Spacers are used in conductor bundles to minimize

wind-induced motions and to keep conductors from

entangling [1] (see bottom of Figure 3.2). If it is such

that the subconductor spacing and configuration of the

spacers allow the subconductors to clash effectively, the

pinch effect force is small relative to the other forces

induced and so may be ignored. Tests in [2] have shown

that this condition is described when either of the

following conditions is satisfied:

u

s

d

s

2

s

I

s

u

Su

u

s

d

s

(3.2)

2.S

I

s

s

u

7u (3.3)

where o

s

is the distance between the midpoints of

adjacent subconductors (m), J

s

is the diameter of the

subconductors (m) and l

s

is the distance between

adjacent spacers (m). The mathematical model used to

calculate the force due to the pinch effect equates the

strain energy in the conductors, coupled with the kinetic

and potential energy in the support structures with the

work done by the electromagnetic forces [2][24].

Removal of the spacers [1][23] and reducing the

subconductor spacing [15][23] decreases the pinch

effect force.

The second phenomenon is known as the swing-out

force, which occurs after the pinch effect [15]. The

influence of the electromagnetic forces cause the

conductors to swing away from one another [24] and

violent motion results [27]. Figure 3.3 shows the

displacement of one of the strain conductors during a

short-circuit test, as documented in [27].

Figure 3.3: Displacement of a strain conductor during

a short-circuit with 47ms interval between dots [27].

During the displacement, the maximum tensile force

which occurs in the conductor, is the swing-out force.

This force can be reduced by using larger phase spacing,

longer spans and greater sags [15].

The third phenomenon is the tensile force caused

after the short circuit, when the conductor falls back to

its original position [26] and is known as the drop force

[2].

An area of major concern for SBS design is the

phase-phase clearance reduction caused by the

displacement of the conductors. If the minimum phase-

to-phase clearance is violated, arcing may occur

between the phases [24] resulting in noise, strand

damage and a decrease in ampacity [15]. The minimum

clearance occurs during a line-to-line fault, where only

two conductors are affected, and the electromagnetic

forces cause them to swing away from each other, as

described earlier. Under the worst case scenario, the

conductors will swing the same distance back to the

inside, resulting in the minimum clearance condition

[26]. During a three phase fault, the centre conductor

moves only slightly due to bi-directional forces acting

upon it from the outer conductors [1][2] and so the

minimum clearance does not occur. It is noted that the

stresses due to both the aforementioned faults are

approximately equal [1][2].

To calculate the tensions, angles and displacements

associated with the swing-out and drop force, the

conductor is mathematically modelled as a pendulum

with one degree of freedom [2][24][26] (Figure 3.4).

SBS short-circuit calculations are performed for summer

and winter conditions separately, as results may vary

quite considerably. The large tensions and

displacements are considered a weakness of SBS [15].

Figure 3.4: Pendulum model for the strain conductor

[24].

The simplified methods for short-circuit force

calculation in SBS are based on extensive research and

produce results that are in good agreement with tests

[1][2][24][26]. In mentioning this, it is noted that these

methods can lead to over-conservative results [28].

Simplified methods for RBS can over-estimate

experimental results by two to six times [1]. Finite-

element methodology (FEM) provides a more

representative calculation. FEM uses computer software

modelling and involves solving the electromagnetic

diffusion equation for discrete points along the busbar

structure [22]. Experiments using this methodology are

presented in [1][9][14][17][21]-[23][28].

4. Vertical deflection and bending stress of

rigid conductor

A rigid busbar conductor can be mathematically

modelled as a beam [2][3][19]. In response to

gravitational loads presented in section 2.1 and 2.3, the

beam vertically deflects. Utilities provide a maximum

allowable deflection requirement, in order to maintain

pleasing aesthetics [1]. For instance, Transpower

provides this requirement in the form of a deflection-to-

span ratio of 1/300 [3]. A difficulty experienced in this

project, was how to approach modelling a concentrated

mass, such as a span connection to other equipment, as

the considered standards [1][3] only provided means to

model uniformly distributed loads. A mechanics of

materials technique known as the method of integration

[29] provided the solution to this problem. The method

involves integrating the moment equation (4.1) twice to

yield a formula for the deflection of the beam as a

function of the distance alo eam, :(x) (m). The

moment equation is

ng the b

E[

d

2

dx

2

= H(x) (4.1)

where E is the Youngs modulus of the conductor (Pa),

[ is the bending moment of inertia (m)andH(x)isthe

internal moment (Nm) as a function of distance along

the beam, x (m). [ measure of how the beam

deflects. For a circula , [ is given by

is a

r cross-section

[ = n

(

c

4

-

i

4

)

64

(4.2)

where

o

and

are the outside and inside diameter of

the conductor (m) respectively. The larger the [, the

larger is the beams resistance to bending. H(x) is the

equation describing the moments (turning forces) that

are created on the beam due to the gravitational forces.

Figure 4.1 shows the deflection of an eight metre long

rigid conductor with and without a 15kg span

connection. The conductor has a diameter of 80mm, a

wall thickness of 4mm and is subject to ice loading. It is

noted from Figure 4.1 (b) that the maximum deflection

has been offset slightly from the centre and that it has

been increased by approximately 4 mm. In this instance,

the deflection would meet Transpowers maximum

requirement of being no more than length/300 mm

(27mm).

During the evaluation of (4.1), the constants of

integration are found by considering the end conditions

of the beam. Bolted connections, as used in Figure 4.1,

are modelled as fixed connections. When a sliding

joint is installed to accommodate thermal expansion of

the tube, as discussed in section 2.4, the vertical

deflection is increased. A sliding joint is modelled as a

roller connection. Figure 4.2 shows the same span

used in Figure 4.1 (b) except with a sliding joint

installed on the left connection. It is noted that the

maximum deflection has been offset quite significantly

in the direction of the sliding joint. The deflection has

increased by approximately 19mm and no longer meets

the criteria specified by Transpower. A solution to this

problem would be to increase the tube dimensions. This

increases [ (4.2), which has the effect of increasing the

conductors resistance to bending.

(a)

(b)

Figure 4.1: Vertical deflection of an eight metre long

rigid conductor due to (a) dead weight and ice loading

and (b) an additional 15kg span connection located

the way along the length.

Figure 4.2: Effect of a sliding joint (left) on vertical

deflection.

The stress on the rigid conductor due to the loads

presented in section two and three cannot exceed a

certain value, else the tube may be plastically

(permanently) deformed or completely fail. For

aluminium, it is recommended that the stress does not

exceed 50% of the yield strength. This takes into

account the strength reduction caused by annealing of

the material during welding [1]. It is statistically

improbable that all of the loads will occur at the same

time, so the busbar system is designed to withstand

certain load combinations, as defined by the utility

[1][3]. The flexure formula relates the longitudinal

stress in a beam to the internal bending moment acting

on the beams cross- ctio [29] (Figure 4.4). This

formula is written:

se n

o

MAX

=

Mc

]

(4.3)

where o

MAX

is the maximum stress (Pa), H is the

maximum bending moment (Nm), c is the conductor

radius (m) and [ is the bending moment of inertia (m).

The presence of a sliding joint increases the maximum

bending moment on the conductor, because it causes

more of the turning force to be subject to the

fixed/bolted end. This results in an increased maximum

stress.

Figure 4.4: Bending stress in the rigid conductor.

Details of implementing the methods presented in

this section can be found in Hibbeler [29] or any text on

mechanics of materials.

5. Other design issues

5.1. Vibration of the rigid conductor

All structures have a natural frequency. A good way to

visualise this, is by taking a ruler, holding one end on a

hard surface, then pressing the free end and releasing it.

The ruler will move up and down at its natural

frequency. If an oscillating force is applied to a

structure, which is near or at its natural frequency, large

oscillations can occur, leading to damage or failu e. This

is the phenomenon known as mechanical resonan .

r

ce

The natural frequency of a rigid conductor,

b

(Hz),

is given by

b

=

nK

2

2L

2

_

L]

m

(5.1)

where K is a constant accounting for the end conditions,

I is the conductor length (m), E is the Youngs modulus

(Pa), [ is the bending moment of inertia (m) and m is

the mass per metre of the conductor (kg/m). K is equal

to 1.25 when there is a sliding joint at one of the span

ends, and 1.51 for two fixed (bolted) ends [1], showing

that a sliding joint causes

b

to decrease. If

b

<2.75Hz,

the conductor may be susceptible to vibrations caused

by wind flowing around it [25]. This phenomenon is

known as aeolian vibration. A damping conductor

should be installed inside the tube to minimise this

effect [1][3]. The weight of the damping conductor must

be taken into account during the RBS design.

Short-circuit forces cause rigid conductors to vibrate

[2]. The frequency of these forces is twice that of the

system frequency, (Hz) [16][19]. Natural frequencies

near and 2 should be avoided [1][3].

5.2. Insulator selection

Loads on the rigid conductor are transferred to the

vertical insulators as cantilever (bending) forces [1][2].

Cantilever forces also arise from loads directly on the

insulator, such as wind and wind-on-ice [1]. Commonly,

insulators are made of porcelain, which has high tension

and compression ratings in comparison to cantilever and

torsional (twisting) ratings [1]. For this reason it is usual

to provide the peak cantilever force at the top of the

insulator, to the manufacturer [14]. This force is usually

given in kN and is found by considering the different

load combinations (see section four). It is recommended

to multiply the cantilever rating by a safety factor [1][3].

Utilities have criteria regarding maximum horizontal

deflection of rigid insulators due to thermal expansion.

For example, Transpower specifies a height-to-

deflection limit of 1/200 [3]. Horizontal deflection is

calculated by considering the rigid conductor elongation

(2.7).This is of course not an issue if a sliding joint is

installed. However, the sliding joint does affect how the

loads on the conductor are transferred to the insulators.

It causes 63% of the load to be transferred to the fixed

(bolted) connection as opposed to equal load division

when both connections are fixed [1].

The selection of insulators for SBS is much less

complicated. Since the insulators are connected to the

conductors in the same longitudinal direction (as

opposed to vertically), they need only to withstand the

maximum tensile force occurring in the conductor.

If not designed properly, insulators may be cracked,

causing a loss in mechanical strength, or completely

shattered [2][15].

5.3. Issues outside project scope

The following topics should be considered for further

development of this project.

Ampacity: Involves calculations that verify the

conductor current carrying ability for different thermal

and physical conditions.

Corona: Considers the minimising of effects due to

corona discharge (ionisation of air) at the conductor

surface, which causes electromagnetic interference.

Seismic loads: Design considerations for the

forces created by earthquakes.

Pinned end connections: Modelling of these types

of end connections for the RBS take into account

fixtures that allow some movement.

6. Design demonstration and comparison

It is the purpose of this section to apply the presented

theory, using the developed calculation sheets (see

section one), to a theoretical design scenario,

demonstrating the processes involved in RBS and SBS

design. A cost analysis is performed to identify which of

the two designs is the most economical. A

comprehensive list of the parameters used will be made

available to the reader upon request.

6.1. Scenario outline

The proposed scenario is based on a design provided by

SKM. The electrical requirements for the busbar

systems are 1) 220kV voltage rating, 2) 1600A current

rating and 3) 40kA (3sec) short-circuit current. For the

purposes of deriving climatic loads, the design is

considered at a location similar to the lower North

Island. The aim of this demonstration is to compare a

four-span RBS against a two-span SBS, each totalling a

length of 64m. The proposed designs are shown in

Figure 6.1. The phase-to-ground and phase-to-phase

spacings are in accordance with [30].

The calculation sheet for the RBS has been verified

against an SKM design in collaboration with an SKM

representative. The SBS version has been verified

against the strain design example provided in Annex I of

[1]. As previously mentioned, both sheets are based on

standards [1] and [3].

6.2. Design decisions and justifications

6.2.1. Rigid Busbar System

On each span of the design, a sliding joint is fitted at

one end to accommodate thermal expansion.

A 15kg span-connection is located at the centre of

the span.

To meet the electrical criteria, an aluminium alloy

6063T5 tube with outside diameter 80mm and wall

thickness 4mm (written 80x4mm) was selected from [3].

This tube has a normal current and a short-circuit rating

of 1670A and 52.4kA respectively. However, the stress

within the material exceeded the maximum allowable

stress of half the yield strength (90MPa) in all load

combinations and caused the vertical deflection of the

conductor to exceed the allowable limit of 53mm (span

length/300) by 406mm (Table 6.1). The dimensions

were increased to 140x8mm, but this was still

inadequate. A 200x6mm tube was the minimum size

that met the criteria.

The natural frequency of the conductor was

calculated to be 3.31 Hz, which is above the frequency

to require a damping conductor for aeolian vibration.

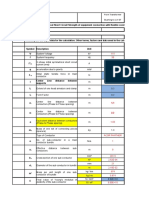

Table 6.1: Deflections and stresses associated with the

considered tubular conductors.

Vertical Deflection (mm)

Limit: 53

Tube Dimensions: 80x4mm 140x8mm 200x6mm

- 459 96 47

Bending Stress (MPa)

Limit: 90

Tube Dimensions: 80x4mm 140x8mm 200x6mm

Load Combination:

Dead +Short-circuit 662 114 69

Dead +Wind 109 40 29

Dead +Ice 125 44 31

(a)

(b)

Figure 6.1: Side elevation and plan views for (a) rigid busbar design and (b) strain busbar design. Dimensions in mm.

The maximum force at the top of the insulators is

5.7kN, provided by the load combination that includes

the short-circuit force. Using a porcelain bending safety

factor of 0.6, in accordance with [3], the minimum

cantilever rating of the insulators used in the design

should be 9.5 kN.

6.2.2. Strain Busbar System

The effect of span-connections on the SBS conductors is

considered negligible as is the case with the example

provided in [1].

To meet electrical requirements, a bundle consisting

of two 415mm AAC conductors was chosen from [3].

This has a normal current and short-circuit rating of

3250A and 48.6kA respectively.

The initial conductor tension was set to 10%CBL,

producing an initial and maximum sag of 0.2m and

0.75m respectively. The height of structure was

increased until the maximum sag of the conductor was

above the required phase-to-ground clearance of 6.64m

[30] and rounded to the nearest half metre at 7.5m. The

sags and minimum clearance are shown in figure 2.2.

The developed QEM approximation (see section 2.4)

was used in the sag calculations and produced a sag

identical to the true result to four decimal places

(nearest tenth of a mm).

The minimum phase spacing due to displacement

during the short-circuit was calculated as 2.93m and

2.17m for winter and summer respectively. The required

phase-to-phase clearance of 2.1m [30] is not violated.

This justifies the design decision to place the conductor

phases 4m apart.

The maximum tensile force acting on the conductor

is 63.5kN due to the drop force during summer. Using a

porcelain tension safety factor of 0.42, as recommended

in [3], the insulator selected requires a minimum tensile

force rating of 152kN.

6.2.3. Supports and foundations

The design of supports and foundations is a structural

task and is considered outside the scope of this work.

For the purpose of attaining a preliminary cost estimate,

supports and foundations have been scaled from similar

designs with guidance from an SKM structural engineer.

It is noted that ground conditions have not been taken

into account during this activity.

6.3. Cost analysis

Table 6.2 shows a breakdown of the estimated costs

associated with each design. The first three entries have

been attained from a local manufacturer and the final

entry is as discussed in section 6.2.3.

The cost analysis shows the aluminium alloy tubes

used in the RBS are more expensive than the aluminium

aerial conductors of the SBS. The costs for the

insulators and fittings associated with both designs are

approximately equal. The large support towers required

Table 6.2: Results of the cost analysis.

Component RBS ($NZD) SBS ($NZD)

Conductors 27,812 5,640

Insulators/fittings 3,040 2,798

Supports/foundations 93,861 408,330

Total 124,713 416,768

for the SBS make up 98% of the total cost as opposed to

75% for the RBS supports. Overall, the strain design is

3.3 times more expensive than the rigid equivalent.

7. Conclusion

Busbar systems require proper design to withstand the

forces in which they are subject to during their

operational lives. The forces considered in this paper

are due to gravity, ice and wind, temperature change

and short-circuits. Relevant theory behind these

loadings is outlined and the electro-mechanical

response of RBS and SBS is discussed. In addition,

vibration and insulator selection is investigated.

Original work includes a novel method for

calculating the final tension in an aerial conductor due

to temperature change and an outline for modelling

concentrated masses on rigid busbar spans.

Based on IEEE and Transpower standards,

calculation sheets have been developed and used in a

design demonstration, with the aim of outlining the

processes involved with each RBS and SBS design. The

demonstration included comparing a four span RBS

against a two span SBS. A cost analysis revealed that

the SBS was 3.3 times more expensive than the RBS.

Topics that should be considered for further

development of this work include ampacity and corona

calculations, consideration of seismic forces and pinned

end modelling for RBS.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Alistair Williams, from

the industry sponsor SKM, for his valuable technical

advice and Dr. Nirmal Nair for his guidance as the

project supervisor. Thanks go to fellow student,

mechanical engineer Elliott Powell, for his derivation of

the deflection calculations and to Kritesh Kumar and

J oan Rey Lawag, also from SKM, for their assistance

with the creation of the CAD drawings in figure 6.1.

References

[1] IEEE Guide for Bus Design in Air Insulated Substations, IEEE

Standard 605-2008, May 2010.

[2] The Mechanical Effects of Short-circuit Currents in Open Air

Substations, CIGRE WG 23-11, 1996.

[3] Guidelines and Information for Buswork Design, TP.DS 01.01-

2010.

[4] HVUBS Short Circuit Testing Design Verification Testing

(undated). Electropar PLP.

[5] D.G. Havard, G.J . Pon, H.A. Ewing, G.D. Dumol, and A.C.

Wong. Probabilistic short-circuit uprating of station strain bus

Appendix - Overview of developed tension

approximation methods

system mechanical aspects, IEEE Trans. Power Delivery, vol.

1, pp. 104-110, J uly, 1986.

[6] Structural Design Actions- Permanent, Imposed and Other

Actions, ASNZS 1170.1-2002.

The change-of-st n uctor tension,

(2.9), can be rearra f cubic equation:

ate equatio for cond

nged to the orm of a

E

2

(A.1) E

]

3

+o

]

+b = u

where I - +

g

2

L

2

L

c

A

c

24

[7] E. Maor, e: the Story of a Number, New J ersey: Princeton, 1994,

pp. 140-141.

o = E

c

A

c

o E

m

i

2

H

i

2

[8] Sag-tension Calculation Methods for Overhead Lines, CIGRE

WG B2.12.3, 2007.

b = -

g

2

L

2

L

c

A

c

24

m

2

.

[9] R. Miroschnik. Force safety device for substation with flexible

buses, IEEE Trans. Power Delivery, vol. 18, pp. 1236- 1240,

October 2003.

]

pr du e

E

]

=

_

-

(H

]

[10] Code of Practice for General Structural Design and Design

Loadings for Buildings, NZS 4203-1992. Further re-arranging o c s

b

+u)

.

Making the assumption that o > E

]

, (A.2) may be

approximated as

[11] D. A. Douglass and R. Thrash, Sag and Tension of Conductor,

in Electric Power Generation, Transmission, and Distribution, 2

nd

ed., L.L. Grigsby, Ed. Florida: CRC Press, 2007, Chapter 14.

(A.2)

[12] J . F Epperson, An Introduction to Numerical Methods and

Analysis, New York: Wiley, 2002.

E

]A

= _

-b

u

. (A.3)

[13] S.M. McCarthy and N-K.C. Nair, Approximation methods for

calculating final tension in an aerial conductor, IEEE Trans.

Power Delivery (to be submitted).

This initial appro matio s refined by applying two

algebraic techniqu n

xi n i

es, produci g

E

](Ln)

=

H

]A

+u

1.5+_

c

[14] J .S. Barrett, W.A. Chisholm, J . Kuffel, C.J . Pon, B.P. Ng, A.M.

Sahazizian and, C. de Tourreil. Testing and modelling hollow-

core composite station post insulators under short-circuit

conditions, IEEE Publication (unnamed), pp. 211-218, 2003.

H

]A

[15] M.B. Awad, and H.W. Huestis, Influence of short-circuit

currents on HV and EHV strain bus design. IEEE Trans. Power

Apparatus and Systems, vol. 99, pp. 480-487, Mar/Apr, 1980.

_

(A.4)

E

)

=

3H

]A

2

+H

]A

_4u

2

+8uH

]A

-3H

]A

2

](uud

6H

]A

+2u

. (A.5)

where E

](Ln)

is the linear error method (LEM)

approximation of final tension and E

](uud)

is the

quadratic error method (QEM) approximation of final

tension. These values can then be used to calculate the

sag of the conductor with (2.2). (A.5) is more accurate

than the former in most applications, but (A.4) is

simpler to evaluate. These approximations were found

to produce very accurate results (see Figure 2.3).

[16] Electrodynamic Forces on Busbars in LV Systems, Schneider

Electric Cahier Technique no. 162, 1996.

[17] D.A. Bergeron, and R.E. Trahan J r. A static finite element

analysis of substation busbar structures, IEEE Trans. Power

Delivery, vol. 14, pp. 890- 896, J uly, 1999.

[18] N.S. Attri, and J .N. Edgar. Response of bus bars on elastic

supports subjected to a suddenly applied force, IEEE Trans.

Power Apparatus and Systems, vol. 86, pp. 636- 650, May, 1967.

[19] J .B. Edwards. Electromagnetic forces on busbars, Journal

IEEE, pp. 30- 32, J anuary, 1962.

[20] Calculation of Short-circuit Currents, Schneider Electric Cahier

Technique no. 158, 2005.

[21] F.M. Yusop, M.K.M. J amil, D. Ishak, and S. Masri. Study on the

electromagnetic force affected by short-circuit current in vertical

and horizontal arrangement of busbar system, Presented at the

International Conference on Electrical, Control and Computer

Engineering, Pahang, Malaysia, J une, 2011.

Using the method of least squares [12], conditions of

validity were established for the two methods. Figure

A.1 shows the minimum temperature change as a

function of span length and initial tension, required for

the QEM approximation to produce a sag within one cm

of the true value. The results are for AAC material.

[22] D.G. Triantafyllidis, P.S. Dokopoulos, D.P. Labradis. Parametric

short-curcuit force analysis of three-phase busbars a fully

automated finite element approach, IEEE Trans. Power

Delivery, vol. 18, pp. 531- 537, April, 2003.

[23] ENEL 380kV Substations: Short-circuit Uprating of Rigid

Busbars Systems and of Flexible Bundled Conductors

Connections between Component, CIGRE WG 23-108, 1998.

[24] D.B. Craig and, G.L. Ford. The response of strain bus to short-

circuit currents, IEEE Trans. Power Apparatus and Systems,

vol. 99, pp. 434- 442, March/April, 1980.

[25] Short-circuit currents - Calculation of effects - Part 1: Definitions

and calculation methods, IEC 60865-1-2011.

[26] B. Herrmann, N. Stein and, G. Kiebling. Short-circuit effects in

HV substations with strained conductors systematic full scale tests

and a simple calculation method, IEEE Trans. Power Delivery,

vol. 4, pp. 1021- 1028, April, 1989.

[27] J .I. Landin, C.I. Lindqvist, L. R. Bergstrom, and G.R. Cullen.

Mechanical effects of high short-circuit currents in substations,

IEEE Trans. Power Apparatus and Systems, vol. 99, pp. 1657-

1665, Oct, 1975.

Figure A.1: Minimum temperature change required for

approximate sag to be within one cm of true sag for

the QEM approximation.

[28] Assessment of the Dynamic Performance of Flexible Busbar

Systems under varying Fault Conditions, CIGRE WG B3 110,

2006.

For more detail, refer to [13], which includes

relevant background material, mathematical derivations,

validity investigations and case studies.

[29] R.C Hibbeler, Mechanics of Materials, 7th ed., Prentice Hall,

2008.

[30] Clearance and Conductor Spacings, TP.DS 62.01-2009.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Development of A Low Sag Aluminium Conductor Carbon Fibre Reinforced For Transmission LinesDocument6 paginiDevelopment of A Low Sag Aluminium Conductor Carbon Fibre Reinforced For Transmission LinesVishalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conductor Sag and Tension CalculatorDocument11 paginiConductor Sag and Tension CalculatorSanjeev KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 132 KV Tower Analysis PDFDocument11 pagini132 KV Tower Analysis PDFViswanathan VÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tower Design SpecificationsDocument8 paginiTower Design SpecificationsInsa IntameenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technical Specification: Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam LimitedDocument9 paginiTechnical Specification: Haryana Vidyut Prasaran Nigam LimitedAdmin 3DimeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loading - Calculations - 12 M Pole 33kVDocument6 paginiLoading - Calculations - 12 M Pole 33kVshreya ranjanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mechanical Short Circuit Strength Calculation for Equipment Connection with Flexible ConductorDocument12 paginiMechanical Short Circuit Strength Calculation for Equipment Connection with Flexible Conductoranoop13Încă nu există evaluări

- Approved - 400kV LADocument22 paginiApproved - 400kV LAGuru MishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACSR Thermal Mechanical White PaperDocument9 paginiACSR Thermal Mechanical White PaperleonardonaiteÎncă nu există evaluări

- CIGRE 2008 A3-207 Int ArcDocument10 paginiCIGRE 2008 A3-207 Int Arcdes1982Încă nu există evaluări

- Is 802 1977 PDFDocument21 paginiIs 802 1977 PDFBhavin Shah0% (1)

- Transmission LinesDocument44 paginiTransmission Linessssssqwerty12345Încă nu există evaluări

- Aac, Aaac, Acsr, Hal, Etc - MetricDocument31 paginiAac, Aaac, Acsr, Hal, Etc - MetricAdiyatma Ghazian PratamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conductor Parameters-SI UnitsDocument17 paginiConductor Parameters-SI UnitsMunesu Innocent Dizamuhupe0% (1)

- Cable Design for Trapezoidally Shaped ConductorDocument1 paginăCable Design for Trapezoidally Shaped ConductorkjkljkljlkjljlkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study On The Electromagnetic Force Affected by Short CircuitDocument5 paginiStudy On The Electromagnetic Force Affected by Short CircuitShrihari J100% (1)

- Creep IEEEDocument45 paginiCreep IEEEPablo DavelozeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Purchase Specification for 30kV Surge Arresters for Balanch SS ProjectDocument6 paginiPurchase Specification for 30kV Surge Arresters for Balanch SS ProjectPritam SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sag-Tension Spreadsheet Free Calculator (Even and Uneven Supports Elevation) - Electrical Engineer ResourcesDocument2 paginiSag-Tension Spreadsheet Free Calculator (Even and Uneven Supports Elevation) - Electrical Engineer ResourcesSlobodan VajdicÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8-P-174 - 220 & 500 KV CTDocument8 pagini8-P-174 - 220 & 500 KV CTAhsan SNÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cable TerminationDocument2 paginiCable TerminationElectrical RadicalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Busbar Design PARWDocument14 paginiBusbar Design PARWJuju R ShakyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACSR Conductor SelectionDocument12 paginiACSR Conductor SelectionSushant ChauguleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analytic Method To Calculate and Characterize The Sag and Tension of Overhead Lines - IEEE Journals & MagazineDocument4 paginiAnalytic Method To Calculate and Characterize The Sag and Tension of Overhead Lines - IEEE Journals & MagazinesreedharÎncă nu există evaluări

- 765kV Greater Noida-Mainpuri Line - Rev 0Document24 pagini765kV Greater Noida-Mainpuri Line - Rev 0Abhisek SurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathlaiya SS 132kV Busbar DesignDocument9 paginiPathlaiya SS 132kV Busbar DesignSantosh GairheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Opgw System FittingsDocument35 paginiOpgw System FittingsRadu Sergiu CimpanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2B P6 MVCC - RDSS - PGVCL - Infra SBD - Part 2 - TS - Version-2 - 28062022Document202 pagini2B P6 MVCC - RDSS - PGVCL - Infra SBD - Part 2 - TS - Version-2 - 28062022Mrugesh Samsung.m31sÎncă nu există evaluări

- Power and Control Cable IEC 60502-1: Flame Retardant, Sunlight Resistant 90 °C / U /U 0,6/1 KVDocument3 paginiPower and Control Cable IEC 60502-1: Flame Retardant, Sunlight Resistant 90 °C / U /U 0,6/1 KVShashank SaxenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sag 340Document15 paginiSag 340tanujaayerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5.surge ArrestorDocument5 pagini5.surge Arrestorraj_stuff006Încă nu există evaluări

- SC Calculations - EditDocument118 paginiSC Calculations - Editeps.hvdc.ocÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electical Calculation EN2021-1132 (220kV)Document3 paginiElectical Calculation EN2021-1132 (220kV)Venu GopalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resistance Grounded Systems: PurposeDocument6 paginiResistance Grounded Systems: Purposerenjithas2005Încă nu există evaluări

- Acsr Moose GTPDocument3 paginiAcsr Moose GTPsomdatta chaudhuryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design Calculation of Oc+15 MTR TowerDocument14 paginiDesign Calculation of Oc+15 MTR TowerGuru MishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aluminium Conductor Sizing - 275kVDocument10 paginiAluminium Conductor Sizing - 275kVsitifarhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calculation of Lightning Current ParametersDocument6 paginiCalculation of Lightning Current ParametersMarcelo VillarÎncă nu există evaluări

- DSLP 11 3mDocument7 paginiDSLP 11 3msureshn829Încă nu există evaluări

- Conductors For Overhead Lines Aluminium Conductor Steel Reinforced (ACSR)Document13 paginiConductors For Overhead Lines Aluminium Conductor Steel Reinforced (ACSR)Sirous EghlimiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 27 Pad Mount TransformersDocument51 pagini27 Pad Mount TransformersRoni Dominguez100% (1)

- 2240 162 Pve U 004 SHT 3 3 01Document13 pagini2240 162 Pve U 004 SHT 3 3 01Anagha DebÎncă nu există evaluări

- Minimum Electrical Clearance. Electrical Notes & ArticalsDocument8 paginiMinimum Electrical Clearance. Electrical Notes & ArticalsJoenathan EbenezerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Power Transformer - 1M - CDocument3 paginiPower Transformer - 1M - CahmedelgharibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electrical Clearance in SubstationDocument3 paginiElectrical Clearance in SubstationpussykhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- DSLP (Control Room) DhamraiDocument3 paginiDSLP (Control Room) DhamraiarafinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vol2 TL-S1-6 3626 PGCBDocument124 paginiVol2 TL-S1-6 3626 PGCBabhi120783Încă nu există evaluări

- GTP For Panther ConductorDocument2 paginiGTP For Panther ConductorPritam SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sieyuan Electric Co., LTD: ClientDocument19 paginiSieyuan Electric Co., LTD: ClientRami The OneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technical Schedule of Surge Arrester 400 KV - ABBDocument5 paginiTechnical Schedule of Surge Arrester 400 KV - ABBmohammadkassarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conductor Design SubstationDocument101 paginiConductor Design Substationt_syamprasadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aluminium Pipe Bus PDFDocument6 paginiAluminium Pipe Bus PDFaviral mishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pages From Electrical Transmission and Distribution Reference Book of WestinghouseDocument4 paginiPages From Electrical Transmission and Distribution Reference Book of WestinghousesparkCEÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11kV Surge Arrestor HE-12Document2 pagini11kV Surge Arrestor HE-12shabbir4Încă nu există evaluări

- Design Manual For HV Transmission LinesDocument9 paginiDesign Manual For HV Transmission LinesbudituxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vertical Loads: F M M KG/M MDocument4 paginiVertical Loads: F M M KG/M MJCuchapinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Electro-Mechanical Design of Rigid A PDFDocument10 paginiThe Electro-Mechanical Design of Rigid A PDFXabi AlonsoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Static Resistance Bolted Circular Flange JointsDocument9 paginiStatic Resistance Bolted Circular Flange JointsBálint Vaszilievits-SömjénÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magnetic Field of Air-Core ReactorsDocument8 paginiMagnetic Field of Air-Core Reactorshusa501100% (1)

- Work Specification For The Construction of 33Kv Overhead Lines Across A Lagoon Using Equal Level Dead-End Lattice Tower SupportsDocument6 paginiWork Specification For The Construction of 33Kv Overhead Lines Across A Lagoon Using Equal Level Dead-End Lattice Tower SupportselsayedÎncă nu există evaluări

- IT Application Guide Ed4Document134 paginiIT Application Guide Ed4K Vijay Bhaskar ReddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Service Manual: CDX-4270RDocument12 paginiService Manual: CDX-4270RburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- High Voltage Skywrap: Fiber Optic CableDocument1 paginăHigh Voltage Skywrap: Fiber Optic CableburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Modify Old Qbasic Programs To Run in Visual Basic: Bergmann@rowan - Edu Chandrupatla@rowan - Edu Osler@rowan - EduDocument7 paginiHow To Modify Old Qbasic Programs To Run in Visual Basic: Bergmann@rowan - Edu Chandrupatla@rowan - Edu Osler@rowan - EduJohn K.E. EdumadzeÎncă nu există evaluări

- EuroEngineering Catalog 2009Document23 paginiEuroEngineering Catalog 2009burvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADSS Fiber Optic Cable Bismon 2018Document4 paginiADSS Fiber Optic Cable Bismon 2018burvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- High Voltage Skywrap: Fiber Optic CableDocument1 paginăHigh Voltage Skywrap: Fiber Optic CableburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- T Rec K.33 199610 W!!PDF eDocument18 paginiT Rec K.33 199610 W!!PDF eVatsanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Optic Fiber Protection Overhead Ground Wire: Other Aluminium ProductsDocument7 paginiOptic Fiber Protection Overhead Ground Wire: Other Aluminium ProductsburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- E907w Wwen PDFDocument92 paginiE907w Wwen PDFDarshana Herath LankathilakÎncă nu există evaluări

- ELEN 7000 - Main Report (Final Submission)Document242 paginiELEN 7000 - Main Report (Final Submission)burvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- T Rec L.26 201508 I!!pdf eDocument24 paginiT Rec L.26 201508 I!!pdf eburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Composite Insulating Cross ArmsDocument4 paginiComposite Insulating Cross ArmsburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- High Voltage Reactive Power Brochure GBDocument20 paginiHigh Voltage Reactive Power Brochure GBburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- ARB OHL CatalogueDocument84 paginiARB OHL Catalogueburvanov60% (5)

- Littelfuse ProtectionRelays SE 330AU Neutral Earthing Resistor Monitor Manual R3Document32 paginiLittelfuse ProtectionRelays SE 330AU Neutral Earthing Resistor Monitor Manual R3burvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alstom Grid - RPC&HF - HV Air-Core ReactorsDocument8 paginiAlstom Grid - RPC&HF - HV Air-Core Reactorsmourinho22Încă nu există evaluări

- Dynamic Response of The Switch Disconnect orDocument7 paginiDynamic Response of The Switch Disconnect orTran Thai DuongÎncă nu există evaluări

- A185716 175Document8 paginiA185716 175burvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technical Catalogue for ConductorsDocument150 paginiTechnical Catalogue for ConductorsGanesh Veeran100% (1)

- Aislador Sediver CompositeDocument16 paginiAislador Sediver CompositeelatoradoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 03Document18 paginiLecture 03burvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Data Sheet Rodurflex Composite Line PostDocument1 paginăData Sheet Rodurflex Composite Line PostburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- High Voltage Reactive Power Brochure GBDocument20 paginiHigh Voltage Reactive Power Brochure GBburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spec6 01 140Document13 paginiSpec6 01 140burvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raychem Stripping Tool For Extruded and Bonded Cable ScreensDocument4 paginiRaychem Stripping Tool For Extruded and Bonded Cable ScreensburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- OH VI 1 Fiber OpticDocument38 paginiOH VI 1 Fiber OpticRochaWillÎncă nu există evaluări

- 380kV DiagonalConnection Brochure 50hertzDocument15 pagini380kV DiagonalConnection Brochure 50hertzburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- 164 - Accurate Simulation of AC Interference Caused by Electrical Power Lines - A Parametric AnalysisDocument7 pagini164 - Accurate Simulation of AC Interference Caused by Electrical Power Lines - A Parametric AnalysisburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- CABLE SYSTEMS FOR ENERGY APPLICATIONSDocument7 paginiCABLE SYSTEMS FOR ENERGY APPLICATIONSburvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shell & Tube Gas Heater Data SheetDocument3 paginiShell & Tube Gas Heater Data SheetRobles DreschÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crazy Taxi Naomi ManualDocument87 paginiCrazy Taxi Naomi ManualbrtnomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elaborate Report Field Testing Pit Emptying BlantyreDocument69 paginiElaborate Report Field Testing Pit Emptying BlantyreAlphonsius WongÎncă nu există evaluări

- VWH Beetle SSP 2011 Lo Res Pt1Document45 paginiVWH Beetle SSP 2011 Lo Res Pt1fabrizioalbertiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chemical HazardousDocument31 paginiChemical HazardousGummie Akalal SugalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Filter Bag EnglishDocument32 paginiFilter Bag EnglishArun Gupta100% (1)

- Aditya Series Ws 325 350 144 CellsDocument2 paginiAditya Series Ws 325 350 144 CellsEureka SolarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Woodwork: Cambridge International Examinations General Certificate of Education Ordinary LevelDocument12 paginiWoodwork: Cambridge International Examinations General Certificate of Education Ordinary Levelmstudy123456Încă nu există evaluări

- Auto Tank Cleaning Machine DesignDocument9 paginiAuto Tank Cleaning Machine Designvidyadhar G100% (2)

- Disclosure To Promote The Right To InformationDocument25 paginiDisclosure To Promote The Right To InformationztmpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bosch EasyAquatak 110/120 pressure washer original instructionsDocument68 paginiBosch EasyAquatak 110/120 pressure washer original instructionsFaizall SahbudinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Service Bulletins,: For Manipulator Systems, Slave Arms, & AccessoriesDocument44 paginiService Bulletins,: For Manipulator Systems, Slave Arms, & AccessoriesKenneth S.Încă nu există evaluări

- Mounting AccessoriesDocument18 paginiMounting AccessoriesJack BaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Four Mark Question Answers Chapter Wise Value Based QuestionsDocument3 paginiFour Mark Question Answers Chapter Wise Value Based QuestionsnitishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sec06 - GroundingDocument6 paginiSec06 - GroundingYusufÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dando Mintec 9000 (Dando Drilling Indonesia)Document2 paginiDando Mintec 9000 (Dando Drilling Indonesia)Dando Drilling Indonesia100% (2)

- Efficient Molasses Mixer for Optimum Massecuite BlendingDocument1 paginăEfficient Molasses Mixer for Optimum Massecuite BlendingRio Fransen AruanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extended End Plate Moment Connections PDFDocument47 paginiExtended End Plate Moment Connections PDFManvitha Reddy100% (1)

- Polycoat Rbe PDFDocument2 paginiPolycoat Rbe PDFAmer GonzalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ce 340-3 GB 7fbestDocument424 paginiCe 340-3 GB 7fbestחנן שניר100% (2)

- Technical Data Sheet Permatex Copper Anti-Seize LubricantDocument1 paginăTechnical Data Sheet Permatex Copper Anti-Seize Lubricant최승원Încă nu există evaluări

- Eutectic Systems: Cu/Ag Eutectic SystemDocument39 paginiEutectic Systems: Cu/Ag Eutectic SystemmatkeyhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise 23 - Sulfur OintmentDocument4 paginiExercise 23 - Sulfur OintmentmaimaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- VFPE Geomembrane Installation For Landfill Capping Applications EngineeringDocument3 paginiVFPE Geomembrane Installation For Landfill Capping Applications EngineeringDAVE MARK EMBODOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bill of QuantityDocument20 paginiBill of QuantityBerry MarshalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structural Design For Embankment Dam BottomdischargeDocument8 paginiStructural Design For Embankment Dam BottomdischargeAnonymous 87xpkIJ6CFÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rick Johnson SNF / PolydyneDocument54 paginiRick Johnson SNF / Polydynezaraki kenpatchiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benefit of Axial Design Waterjet Propulsion - Wartsila PDFDocument20 paginiBenefit of Axial Design Waterjet Propulsion - Wartsila PDFPandega PutraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Refrigeration and Liquefaction Processes ExplainedDocument26 paginiRefrigeration and Liquefaction Processes ExplainedJolaloreÎncă nu există evaluări

- C2 Metallic Bonding Answers (Rocket Sheets)Document1 paginăC2 Metallic Bonding Answers (Rocket Sheets)Maria CamilleriÎncă nu există evaluări