Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Integrity in The Care of Elderly People, As Narrated by Female Physicians

Încărcat de

ravibunga4489Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Integrity in The Care of Elderly People, As Narrated by Female Physicians

Încărcat de

ravibunga4489Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

INTEGRITY IN THE CARE OF ELDERLY PEOPLE, AS NARRATED BY FEMALE PHYSICIANS

Ann Nordam, Venke Srlie and R Frde

Key words : ethics; female physicians; geriatrics; narrative Three female physicians were interviewed as part of a comprehensive investigation into the narratives of female and male physicians and nurses, concerning their experience of being in ethically difficult care situations in the care of elderly people. The interviewees expressed great concern for the low status of care for elderly people, and the need to fight for the specialty and for the care and rights of their patients. All the interviewees narratives concerned problems relating to perspectives of both action ethics and relational ethics. The main focus was on problems concerning the latter perspective, expressed as profound concern and respect for the individual patient. Secondary emphasis was placed on relationships with relatives and other professionals. The most common themes in an action ethics perspective were too little treatment and the lack of health services for older patients, together with overtreatment and death with dignity. These results were discussed in the light of Lgstrups ethics, which emphasize that human life means expressing oneself, in the expectation of being met by others. Both Ricoeurs concept of an ethics of memory and Aristotles virtue ethics are presented in the discussion of too little and too much treatment.

Introduction

The care of elderly people in hospital in Norway has been described as existing in a state of crisis for more than a decade. There are few gerontologists working in Norwegian hospitals, and none in nursing homes. In the period between 1991 and 2001, 1000 new positions were established for physicians in Norwegian hospitals, while the corresponding number for nursing homes was zero.1 The number of beds available by no means covers the actual need in either hospitals or nursing homes.2 The seriousness of this situation is further accentuated by demographic and disease pattern developments, which are leading to an increase in the number of older people, a reduction in the incidence of fatal diseases, and an increase in the

Address for correspondence: Ann Nordam, Centre for Medical Ethics, PO Box 1130, Blindern, N-0317 Oslo, Norway. E-mail: a.r.nordam@medetikk.uio.no

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4) 2003 Arnold

10.1191/0969733003ne589oa

Integrity in the care of elderly people

389

incidence of chronic diseases. There are more older people with a longer life expectancy, but who suffer from diseases and impairments. The result is an increased need for health services.3 A report on the consumption of health services by elderly people in the 1990s indicates that demographic developments imply that the number of hospital beds should be increased by somewhere between 3000 and 7000 in the next 50 years if current supply and admission criteria are applied. 4 The mass media have frequently raised the issue of the undignified conditions suffered by elderly patients in community nursing facilities, nursing homes and hospitals. The conditions in nursing homes have received particular attention because the lack of both qualified nursing personnel and economic resources have resulted in the re-use of disposable nursing products.5 A report on regional physicians supervision of the health care services provided for older people in the community revealed that there are substantial deficiencies in the fulfilment of such basic human needs as food, personal hygiene and general care.6 Elderly people are not a homogeneous group. Being old, and being old and sick, are two different things. Old age is characterized by two processes: the normal ageing process that affects everyone; and the so-called diseases of old age, which afflict some but not all. 7,8 Older people have fewer physical and mental resources, are more vulnerable, and need longer convalecense than younger people. Making a diagnosis is difficult because the symptoms may be vague, and side-effects and low drug tolerance are common.8 The intertwining of ageing and disease processes makes it difficult to distinguish between disease and normal changes related to age; this can lead to both over- and undertreatment. 9 Older people often have several concomitant diseases, especially those who are over 80 years of age. When this occurs, symptoms may be enhanced, diagnosis becomes more uncertain, and treatment is more complicated. These factors combined can result in unnecessary medication, but also increased morbidity, dulling of the mind and, in some instances, hastening of death.10 Considering the expertise required and the challenges posed in caring for elderly people, it could be expected that the specialty would have a high status within the medical profession, but in fact the contrary applies. An investigation among Norwegian physicians showed that care of elderly people is assigned the lowest position in the hierarchy of prestige, with psychiatry and chronic diseases such as rheumatology just above, while heart surgery, transplant surgery and neurology are at the top of the list.11 These factors indicate the degree of esteem in which older people are held by physicians, the health services and society in general. The treatment of older people is challenging and demanding work, medically, existentially and ethically. Considering the lack of resources in the care of elderly people today, these challenges create a sense of powerlessness and contribute to staff seeking employment elsewhere in the health services. Physicians tend to want to work in emergency medicine and prefer to work with groups of younger patients, in which the goals of medicine (i.e. saving life, restoring health and achieving complete recovery) are likely to be realized. Consequently, the medical treatments of older people are not prioritized, despite the fact that this group of patients fulfil the criteria for serious disease and therefore need effective treatment.12 The imperative to save life in medicine has given rise to the hypothesis that physicians responsibilities often lead to an emphasis on action ethics, with the

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

390

A Nordam et al.

focus on treatment and considerations of justice.1315 Action ethics focuses on: What should/ought I/we do? This perspective centres on the reasons for acting in a certain way. The question What should/ought I/we do? requires an answer; implicitly, it requires a choice of action that proves ultimately to be the right course of action. The requirement to do the right thing is justified in various ethical traditions, such as consequentialism, casuistry, deontological ethics and principle-based ethics. The latter is used widely in both nursing and biomedical ethics.16 However, investigations reveal that physicians alternate between emphasizing an action ethics and a relational ethics frame in their narratives concerning ethically difficult situations in surgery, care of elderly people, and paediatrics. 15,17 Relational ethics focuses on how we as human beings are challenged in situations and in our relationships, and how we meet these challenges in a morally acceptable way. The challenge is to understand life from our own experiences of vulnerability and fragility, and as humans exposed to each other and being interdependent. 18 The fundamental questions are: Am I a good physician? Am I, as a physician, meeting the ethical demand of the other? The qualities that make a good physician are not only personal traits but they depend on the demands of the situation.19 This somehow brings together a relational and a virtue ethics perspective because virtue ethics is sensitive to the demands of the situation and focuses on the virtues expressed in action in a given relationship. Some empirical studies have been performed that explore the moral reasoning of health care professionals in geriatrics. 15,20,21 One study revealed no gender differences, either in the form and content of the moral reasoning disclosed or in showing a care or a justice orientation.15 This is consistent with the findings of Ford and Lowery, with the exception that they found women to be more consistent in their use of a care orientation.22 An analysis of physicians, registered nurses (RNs) and enrolled nurses (ENs) stories about the care of older patients showed that the physicians were preoccupied with criteria for the selection of those who ought to receive treatment, and the appropriate level of care. The RNs emphasized quality of life, and over- and undertreatment of patients. The ENs stories were patient- and relationship-centred and concerned everyday situations .21 Other researchers in the geronotology field have employed other perspectives (e.g. of consumers and gerontological policy). These studies have shown that some of the key issues in the care of older people are dignity and autonomy.23,24 The international literature also suggests that the maintenance of high standards in preserving older peoples dignity and autonomy may be a global problem.24 Team-work is a necessary component in ensuring the health and well-being of more older people. This fact, and data showing that ethical decision making in nursing is profoundly influenced by phyiscians, colleagues and the organization, point to the relevance of physicians experiences of ethical dilemmas to nursing practice. 25 The aim of this study was to illuminate the meaning of being in ethically difficult situations when caring for elderly people, as experienced by female physicians. This is part of a comprehensive investigation of ethical thinking among female and male physicians and nurses who care for elderly people.

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

Integrity in the care of elderly people

391

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were all female physicians (n = 3) working on geriatric wards at a university hospital in Norway. Their working experience in medicine and geriatrics was between seven and 20 years. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the 5th Health Region in Norway. The physicians gave their informed consent to participation in the study.

Interviews

The second author conducted the tape-recorded narrative interviews, which lasted for between 30 and 140 minutes (mode = 75); they were transcribed verbatim by the first author. Interviewees were asked to narrate care situations they had experienced as being ethically difficult in their work as physicians in the care of elderly people. The aim was to understand the meaning of their experiences. The concept of an ethically difficult situation was not defined, the question being left open for the respondents to define what they themselves had experienced as ethically difficult situations. Questions were asked only when the interviewer wanted the interviewees to elaborate their story or had difficulty with understanding the narration (e.g. What did you do, think or feel then?)26

Interpretation

The interviews were analysed and interpreted by using a method of interpretation inspired by Ricouer s phenomenological hermeneutics.2729 This was developed at the University of Troms and Ume University, and has previously been used by Lindseth et al.,30 Norberg and Udn,15 Norberg et al.21 and Sundin et al.31 This method focuses on the meaning of peoples narrated lived experiences. The interpretation proceeds through dialectical movements between understanding and explanation. The first naive reading is a superficial reading of the text as a whole, to gain an overall impression and an initial grasp of the content. The naive reading shows the direction that the structural analysis should take. The structural analysis is directed towards the structure of the text in order to explain what the text is saying. It includes examination of parts of the text in order to validate or refute the initial understanding obtained from the naive reading. The third phase the interpreted whole is an in-depth understanding based on the naive reading, the structural analysis, and the authors pre-understanding. The interpreted whole is developed in the light of conceptual frameworks with the aim of gaining a deeper understanding of the text. A naive reading was made of all the transcribed interviews to gain a first impression of the meaning of the text as a whole (i.e. the interviewees lived experiences of being in ethically difficult situations during their clinical work as geriatricians). The naive reading was done as open-mindedly as possible, without any deliberate attempt to analyse the text. In the next phase, the structural analysis, the interviews were divided into meaning units (i.e. one sentence, parts of sentences or a whole paragraph with a related meaning content). The meaning units

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

392

A Nordam et al.

were condensed and discussed among all three authors, and themes and subthemes were identified. Finally, a critical overall understanding was developed, taking into account the authors pre-understanding, the naive reading and the structural analysis. The text was read as a whole and understood in relation to theories of ethics and investigations into the meaning of being in ethically difficult care situations, leading to the formulation of a comprehensive understanding.

Results

Naive reading

The naive reading revealed that the most prominent feature of the narratives was the focus on relationships, particularly expressed as concern and respect for individual patients, and secondarily on relationships to relatives and relationships between professionals. Other recurrent themes were respect for the specialty, elderly patients, and patients as individuals. The difficulties of making medically and morally good decisions were put into focus, on the one hand concerning too much treatment and achieving death with dignity, and, on the other, too little treatment and the lack of resources allocated to the care of elderly people.

Structural analysis: relational ethics perspective

Focusing on individuality and dignity: (1) Seeing older people as individuals The physicians emphasized the great variation in the work with older people. The wide individual personality differences among older people and the spectrum of diseases encountered made the female physicians feel that elderly people are more exciting, both as people and patients, compared with those who are younger:

It is far from the case that they [older people] are a homogeneous group. They perhaps get more individual when they grow older. I think it is because they are able to say what they want, they might feel that they do not have much time left, and during that time they have to get the best. They fascinate me. Some of them have a lot to give as fellow human beings.

An appreciation of the individual qualities and characteristics of patients was important to the physicians, even if older people are not productive in society. The physicians emphasized that older people have lived a long time and have acquired much wisdom from life. It was therefore important for physicians to listen to patients in order to meet them in an individualized way. At the same time it could be difficult to meet some elderly people in an appropriate manner because they may sulk and complain:

I think many of those I meet are well balanced; they have come to terms with many things in life. It always fascinates me the ability people have to live through all the phases in life. But then you also have those who are chronically discontented. But even that provides a picture of how humans can develop, and even that patient gives me something.

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

Integrity in the care of elderly people

393

Demanding patients can be hard to relate to, especially if they demand more than is strictly necessary in the physicians opinion: Especially if you are exhausted, and then try to take a positive attitude to those who almost put a drain in your brain. Focusing on individuality and dignity: (2) Protecting the vulnerable The stories disclosed that these physicians felt especially responsible for the weak and vulnerable patients who do not demand anything. They expressed that it is necessary to fight for the silent patients, in particular those suffering from dementia.

You never know. Think about it, what if suddenly one day you become demented and sit there with drool on your chin and your left shoe on your head, and nobody cares.

The interviewees expressed the need to protect the integrity of patients and confirm their value as human beings, especially if they are young elderly people. They told stories about patients feeling they had little value, and that they felt they were a burden. This included both older and relatively younger patients. The physicians were concerned about the way in which the media handles certain issues, especially that of active euthanasia. Newspapers have reported stories about physicians performing active euthanasia in Norway, and the media in general has raised the debate about legalizing it, referring to the practice in the Netherlands.

We had a relatively young patient and he asked a straightforward question about euthanasia. He said: Well I do not really have any value because I am so ill. It is only a burden that I go on living. He really became invigorated when I told him about my point of view.

The physician opposed active euthanasia saying: A life is a life. This confirmation from the physician gave the patient a feeling of being protected: It was obvious that he had been thinking about it. Some patients have very low self-esteem, and their expectations of the health services are also rather low, which is connected with their feeling that they are not worthy of medical attention: I said, You have a life; you have no less value than a child, and I think she felt that was good to hear. Focusing on relationships to patients: keeping a balance between closeness and distance The physicians referred to their own lives by saying that being able to establish good contacts with older people and feeling empathy with them is related to their close and positive childhood relationships with their grandparents. As one physician said: For many years I had a very good relationship with my grandparents. I have always liked elderly people. A close relationship based on trust was seen as fundamental to understanding the expressions and needs of patients. The physicians described the difficulty of finding a balance between being involved and engaged in the patients situation and reaching the point where one has to maintain a distance from patients in order to survive:

You distance yourself in a way because you cannot involve yourself in every [patient] as if [he or she] were your close relative. You cannot manage that, but at any rate you remember them so well.

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

394

A Nordam et al.

Focusing on professional relationships: (1) Accepting ones own vulnerability and fallibility The physicians expressed that they would never hesitate to call for supervision from a more experienced physician in critical care situations, even if they may be criticized by colleagues. Ethical difficulties occurred when physicians were afraid of asking for help or of making medical mistakes. Openness within the team was fundamental to accepting ones own vulnerability and fallibility. These female physicians emphasized that lack of courage and openness may lead to arrogant behaviour owing to insecurity. This problem is related to a fear of not being able to answer all the questions raised by patients and co-workers because some physicians feel that they have to be omniscient: Some physicians feel that they have to be infallible and it is very difficult to come down from that pedestal. The burden involved in making decisions is having the ultimate responsibility for the decisions being made. The physicians discussed difficult situations concerning care and treatment with other professionals, but, because they have the final word, they feel lonely. Uncertainty about whether their decisions are right is a feeling physicians often have, and this adds to the burden. However, the burden of responsibility weighs less heavily on them as the years pass and they gain more clinical experience:

I cannot be a hundred per cent certain, but I try to see whether this is in accordance with my own moral views, and what I think is the right thing to do.

Focusing on professional relationships: (2) team-work Doing a good job is closely connected with contributing to and enhancing teamwork. It is important to be able to acknowledge co-workers and to ensure that they are not becoming exhausted. The physicians described their work as demanding. At the same time it was important to promote a fighting spirit in the team, which contributes to everyone doing their best for the patients. They emphasized respect for and dependence on co-operation with other professional groups to improve outcomes for patients. In particular, their co-operation with nurses was described as good:

I feel that we function as a united front, of which I am merely a part. You have the final responsibility, but I have never felt that team-work is a problem. I have never experienced any conflicts among professionals.

The positive and supportive collegial environment among physicians involved in the care of elderly people was emphasized. The openness and extent of discussion concerning treatment or nontreatment, as well as the support they say they received from other physicians, was marked. The physicians stated explicitly that ethical problems are often discussed:

It is discussed more often than people think. It is not the case that one of us makes a decision and then that is the way it is going to be.

The lack of conflict and a good working environment was pronounced:

Nobody has elbowed their way . . . the working environment is decent. Never any big conflicts. All in all I think it is very positive. It has often saved a strenuous working day.

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

Integrity in the care of elderly people

395

Structural analysis: action ethics perspective

Relatives as decision makers When these physicians were having to make difficult decisions (e.g. whether they were going to continue or discontinue treatment) they felt that being pressured by relatives to continue treatment influenced their decision. Close relatives sometimes want intensive treatment of patients in a terminal stage. If the physicians acted in opposition to such wishes and decided to allow patients a peaceful death, they felt that they were killing them. The physicians also experienced negative reactions from relatives when patients themselves did not want further treatment at the end of life but relatives wanted them to continue:

He would not acknowledge that his mother was dying. And we were continuing a treatment that in many ways we felt pressured to give, much longer than I really wanted to.

The physicians believed that patients were not being listened to or respected because they were old:

He didnt want to be admitted. They almost coerced him to be admitted, and two days later he died. Such episodes are painful. That is steamrolling the patients.

The narratives disclosed that wives in particular expected physicians to give extensive treatment to their husbands. The same phenomenon was also revealed in childless couples who had had only each other for the whole of their adult lives: Women especially react as if it is their child who is going to pass away. Denigrating patients The physicians did not agree with and opposed the tendency to medicalize older people because of their age. They believed that there is a lot of prejudice against older people in society and in the health sector:

Older people have never had any status in society, at least not in recent years. I have a feeling that older people are just seen as wreckages. I think there are a lot of hidden mechanisms like that, and the care of elderly people does not have status within medicine.

They narrated that elderly people in general, and older patients, are not seen and met as individuals. Elderly patients are often declared incapable of managing their own affairs, and health care routines are given highest priority, not the needs of patients. It was frustrating for these physicians that elderly patients are not respected and not prioritized compared with younger patients. They considered that elderly patients rights are being infringed (e.g. they are not receiving rehabilitation services, or are not given appointments with specialists). They also noted that those who have responsibility for the allocation of resources show little respect for elderly patients:

Speaking of ethical dilemmas, the greatest frustration is the indifference of those who allocate the money a kind of strange disregard for the patients. It makes me quite depressed, especially because some older people are treated like parcels and sent east and west.

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

396

A Nordam et al.

Denigrating the care given to elderly people On the administrative and political levels there is very little understanding of how demanding a specialty the care of elderly people is. The physicians pointed to the fact that geriatrics and psychiatry are ranked lowest among the medical specialties. They believed that the health administrators have a very cold and cynical attitude towards this aspect of medicine:

When they make public speeches it sounds pretty good, but I often feel that it is very cynical, and that is extremely frustrating. I think many feel that, and this is an interesting point, that the trade union is being muzzled. We are not allowed to make statements, only about certain specified topics. We can lose our jobs if we state our opinion publicly, and this is happening in democratic Norway. It makes me very angry. Such conditions make the working day difficult.

The physicians revealed that the cuts in public spending are affecting what they think is medically justifiable: The question is how far can you go for the sake of your own conscience as the patients advocate. They expressed that they do not have enough time for patients and there are too few resources in terms of personnel. This affects the supervision of newly employed physicians. Because there are too few physicians, they do unpaid overtime and thus have less leisure time. The physicians believed that administrators take advantage of this because no doctor willingly leaves his or her patients. Challenges occurring in the care of elderly people seem to be of little interest to the other medical specialties. Saving life has always had the highest priority and, as a result, there seems to be nothing heroic about caring for elderly people. The physicians revealed that the lack of resources and pressure of work are leading to less contact with and closeness to patients and relatives. Information about patients has to be obtained from the nursing staff. They wanted to have more time to talk to patients. It is always the contact with the patients that suffers. Too much or too little treatment: (1) Death without dignity The physicians stated that there is a risk of too little treament being given to patients who are suffering from dementia because they have reduced mental capacities, and also to patients who are suffering from depresssion. They emphasized that it may be difficult to understand what patients mean when they say that they do not have anything to live for, and this entails a risk of not initiating treatment.

You must be acquainted with the patients. When they say that they do not have anything to live for, they actually mean it, but this does not imply that they want to die.

The physicians faced a dilemma when patients stopped eating and drinking. The difficulty is to decide whether this is a genuine wish to die or the result of depression. This is a difficulty they often encounter because depression is a common problem among elderly people, and one that is frequently undiagnosed and untreated:

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

Integrity in the care of elderly people

397

There is a lot of depression among older people; their families have more than enough to do with themselves and they feel that nobody needs them any more. They are lonely and their friends have died, so there are a lot of different factors. They may seem demented because they cannot keep track of what day it is. It doesnt matter to them, because they are not interested in knowing that.

Too much or too little treatment: (2) Death with dignity There is a risk that diagnostic procedures will be carried too far, resulting in putting too heavy a strain on patients. In situations where physicians subject patients to overtreatment, they may remember this many years later:

In this case I chose to send her for an operation and she came back and died within a short time. It is this kind of patient who can haunt you afterwards. With hindsight she should probably not have been operated on. What bothers me is the fact that she was mutilated. It is an ugly word, but it was actually how I felt it, that I had contributed to it. It is very unpleasant to live with this afterwards. Sometimes you get these flashbacks. You see the poor patient who you have been sending around the system.

When these physicians had to make a life-and-death decision, they found it difficult to take into account the total situation, which they nevertheless felt was necessary if they were to make the right decision. In addition, the patients wishes must be taken into consideration and dealt with more positively. The physicians emphasized that it can be problematic to allow older people to die:

It is important to stop [the treatment]. It is one of our tasks as physicians in the care of elderly people to say, Enough is enough. We have to discuss this. Some cases cause conflict if we do not stop in time. At the same time it is important not to stop too early. It is an eternal conflict we face.

Great emphasis was placed on listening to and respecting the patients wishes with regard to medical diagnosis and treatment. Death with dignity was a recurrent theme in the narratives:

There are patients who have had a long and good life, who are mentally lucid, and who do not want to undergo more diagnostic procedures. They want to die in peace. When they are admitted to hospital they are subjected to things they dont want to have happen. We should respect that. We should not start examining and treating them. We should listen to and hear what the patient wants.

The importance of a worthy and qualitatively good death was stressed (i.e. one day of good quality life is better that three qualitatively bad days). It was of great importance for the physicians decisions that they reflected over their own life experiences and tried to put themselves in their patients place:

I always try to think, what if this was one of my own relatives, because that is the only criterion I have. I do not have any other criteria.

The physicians interpretations and understanding of the relationship between patients and relatives was essential for their decision making concerning termination of treatment. They believed that it is difficult but important to confer with relatives in order to evaluate what resources they have, and what kind of relationship they have with the patient.

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

398

A Nordam et al.

Comprehensive understanding

These female physicians had entered the field of geriatrics from other medical specialties. They expressed great respect for this challenging and complex, but rewarding, specialty. The results demonstrate that respect for patients and preserving dignity, in the sense of valuing patients and promoting their self-respect, were seen as fundamental aspects of establishing and maintaining an ethically good relationship. Furthermore, these relational aspects were seen as basic to the making of sound medical decisions. The female physicians were attending to the medical needs of the patients and stressed the importance of maintaining their integrity by seeing them as individual persons, not merely as patients. Respecting individual patients and appreciating their individual characteristics were seen as basic values expressed in seeing, listening, hearing and sensing what the patients are expressing. The physicians allowed themselves to be emotionally touched and moved by their patients. The ethical demand to meet the other was sensed especially in the case of those who are silent, vulnerable and undemanding. The primacy of relationships in human life and ethics echoes the writings of Lgstrup,18 according to whom our lives are fundamentally intertwined. From this it follows that we are not independent but exposed to each other. Human life means expressing oneself with the expectation of being met by others. The ethical demand emerges directly from the fact that, metaphorically speaking: A person never has anything to do with another person, without holding some part of his life in his hand.18 Human interdependence is particularly salient in situations when people are in need of help (i.e. in contexts of disease, disability, pain and suffering). The interdependence and the expectation of being met are not restricted to such situations but present in all our encounters with others:

Regardless of how varied the communication between persons may be, it always involves the risk of one person daring to lay himself or herself open to the other in the hope of a response. This is the essence of communication and it is the fundamental phenomenon of ethical life.18

Trust is in a basic sense fundamental to all communication, as we deliver ourselves into the hands of the other.32 This surrendering of self makes us vulnerable because the other can hear the tone in what we say or can ignore it. The ethical demand is to answer the appeal from the other, to take care of what he or she has placed in our hands. Our existence demands of us that we protect the life of the person who has placed his or her trust in us.18 Answering the appeal from the other may fail because obstacles are placed between the physician and the patient. Such obstacles may be too much focused on diagnosis and treatment, which take precedence over the relational aspects. One female physician had flashbacks of a situation many years earlier, in which she felt she had contributed to the overtreatment and mutilation of a patient. She expressed that this situation haunted her and she could not forget it. This phenomenon may be understood in the light of Ricoeur s ethics of memory: the physicians never will, can, or must forget.33,34 Situations that are carried in their memories are paradigmatic in the sense that they have failed to do their best for the patient or to do him or her good. These situations have become indelibly

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

Integrity in the care of elderly people

399

printed on their memories. Ricoeur 35 uses as an example of the phenomenon you must not forget, the atrocities committed especially against the Jews during World War II. It can be claimed that this is an extreme example, but the main point is that some events take place that are associated with feelings of extreme discomfort, and the memories of them are haunting. From this perspective, feelings of loneliness and uncertainty among physicians are understandable. The physicians emphasized the burden of decision making and the loneliness and uncertainty they felt in critical care situations. It seems that as human beings we remember ethically difficult situations because the memory of them activates our ethical reasoning and judgement. They function as paradigmatic exemplars of how we should not act. The negative feelings associated with such negative exemplars (uncertainty, discomfort and loneliness) have a positive side to them because human beings are free to remember what is at stake in their lives and can interpret the ethical demand in their responsibility for others.36 When physicians allow themselves to be emotionally moved by a patients appeal, although feeling uncertain, lonely and vulnerable, they can do good (or bad). Listening to the voice of conscience requires courage. This courage comes from life itself, as expressed by one physician: As you gain more experience you become less uncertain, but you can never be a hundred per cent certain that this is the right thing to do. The physicians referred to their own life experiences as relatives and friends; they emphasized the good relationship they had had with, for example, their own grandparents. This may explain the emphasis on dignity and respect they felt for elderly people. They had positive memories going back to their childhood, and they listened to the voice of conscience. In addition, the results indicate that the positive and good experiences are, if not of equal importance, at least significant for reflecting and actually developing the openness to be able to sense and answer the demand from the other. This is connected with developing moral integrity. Considering the meaning of the word integrity as intact and whole, I protect my moral integrity by doing what I feel is the right thing to do . . . ultimately moral integrity is all about self-respect which benefits fellow human beings, the other.36 The demand that the other be accepted is not clear and explicit. It is silent, nonexplicit and is not to be equated with a persons expressed wish or request.18 We must ourselves find out what the other person is demanding from us. In Lindseths interpretation of Lgstrup, this necessitates not only a willingness to hear what the other is saying, but also an alertness to the tone of what is said, to the unspoken content of the silence, body language and relationship and situation.37 A willingness to interact and act in sensuous proximity to the other person was expressed by the female physicians when they interpreted situations where patients said they did not have any value as human beings. One physician recognized the vulnerable expression of one patient and confirmed her individual value by saying that her life was as valuable as that of a child. Other narratives revealed how these female physicians interpreted contexts in which patients stop eating and drinking, saying they have nothing to live for. The physicians emphasized that this does not mean that these patients want to die. Such an expression from a patient may be the result of depression and feeling a

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

400

A Nordam et al.

burden to family and to society. The physicians did not take the words spoken at their face value but were alert to the tone and the unspoken content, trying to find out what the patient was really demanding. As Lgstrup himself points out: The situation may be such that I am challenged to oppose the very thing the other person expects and wishes me to do for him or her, because this alone will serve his or her best interests.18 Virtue and moral integrity are closely related concepts, and they are expressed in the narratives that concern too much or too little treatment. Going back to the ethics of memory, one physician spoke about hindsight and discomfort because the result was unworthy (the patient had been mutilated). The physicians also spoke about the inability of relatives to accept that the end of life was approaching for a patient, which led them to continue futile treatment. These memories had not resulted in bad conscience, but in reflection and a coming to wisdom after the event, making them more focused on sensing and answering the appeal from the patient. This is an expression of what Aristotle calls practical wisdom (phronesis ) or the practical knowledge of a virtuous person.38 The female physicians were aware of the problems connected with giving too much treatment because this could lead to an undignified death. At the same time they presented situations in which they could provide too little treatment, especially for demented or depressed patients. They were not speaking about the issue of death with dignity, or in terms of health care allocations and priorities, nor in a consequentialist sense of weighing the positive and negative consequences of different courses of action. What the narratives revealed is that they were striving to find the balance between too much and too little treatment (i.e. the middle path, which, in Aristotles works, constitutes the virtuous). Virtue is central between two extremes (e.g. courage is between the vices of foolhardiness and cowardice). The virtue of courage is used as an example here because morality and implicitly professional integrity are intertwined concepts expressed in acts that demonstrate practical wisdom. The narratives showed that these female physicians were aware of their own vulnerability and fallibility, expressing neither extreme, but courage. Answering an ethical demand from a patient can imply that physicians are acting against relatives wishes concerning continuing treatment or its cessation. This requires courage, which is an expression of intact moral integrity. Acting in a way that fulfils self-integrity is an expression of virtue.36 In these narratives, the centre is expressed as the mid-point between too much and too little treatment, leading to indignity, which, in Aristotles concept, constitutes vice. What the physicians narrated was that they were approaching this middle path the virtuous by reflecting on difficult care situations and through open dialogue with co-workers and colleague physicians. The dialogue and discussion occurring with other professionals in the care of elderly people is worth noting because it is completely absent in paediatric pratice. 17,39,40 Reflection, open discussion and memories enabled the female physicians to deliberate, which is always necessary when making decisions in a patients best interests. Doing good in the sense of finding the middle way is no easy task because it involves doing this to the right person, to the right extent, at the right time, with the right motive, and in the right way; that is not for everyone.38 A virtuous person is capable of doing the right thing in the right circumstances and, through ethical reflection, gains a conscious understanding of who she or he is and what she or he is doing.

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

Integrity in the care of elderly people

401

Reflection on ones own character, and the ensuing self-acceptance or self-criticism, may be an activity which is at once motivated by the virtues, an expression of the virtues and a manifestation of human freedom.41 The right and good act always depends on the context, and, quoting Aristotle, this means that: the decision rests with perception.38 This implies that it is impossible to make guidelines or rules about what conduct is right; it always depends on the conscious sensitivity of the demands of the situation.

Methodological considerations

The small number of participants in this study was insufficient to allow inferences about the incidence of the observed phenomena in the background population. However, the aim of qualitative studies is not to fulfil the traditional claims of validity, reliability and generalizability that are required in quantitative research. In-depth interviews do ensure representation in relation to transferability, because they permit deeper insight into the phenomena under study, thus the complexity of detail in the data.42 Against this background it can be stated that qualitative projects show a high degree of content validity if people with similar experiences can recognize the descriptions and interpretations as their own.43 The distinction between an action and a relational ethics perspective may seem artificial. However, it is analytically productive because it helps to structure the data, and also because the two perspectives have two distinct focuses, namely an explanation of choices of action and how we as human beings are challenged in situations and relationships in life. In practical clinical work, these two perspectives are intertwined because it is difficult to determine what are the right course of action and acting in the best interests of the patient, unless a good relationship is established with the patient at the outset. This means that the two perspectives are not mutually exclusive; quite the opposite, they are complementary because morally justifiable conduct has to include both perspectives.

Conclusion

In this study, female physicians focused mainly on integrity, both in the sense of a profound respect for the care of elderly people as a medical specialty, the integrity of patients and their own integrity as physicians. They were preoccupied with doing what was right and best for individual patients. A prerequisite for this was establishing an ethically good relationship, as was expressed in their emphasis on seeing and meeting the individual patient. The importance of making a moral commitment in medical contexts has been described with reference to paediatric care because commitment in this context raises complex medical, relational, existential and emotional issues.44 The narratives analysed and interpreted in this study confirm this complex picture also in the care of elderly people. They reveal that the traditional picture of medicine as dealing with and handling biomedical facts expertly, from a stance of professional distance from the patient, is inadequate for grasping the complexities involved.

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

402

A Nordam et al.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Norwegian Research Council and the University of Oslo. The authors are grateful to the participants in the study and to Ms Pat Shrimpton for revising the English. Ann Nordam, Venke Srlie and R Frde, University of Oslo, Norway.

References

1 2 3

5 6

7 8 9

10 11 12

13 14 15

16 17 18 19

Huseb, BS. Medisinske feil i sykehjem. (Medical mistakes in nursing homes). Omsorg Nord Tidsskr Palliat Med 2001; 1: 4750 (in Norwegian). Government White Paper no. 50. Handlingsplan for eldreomsorgen (Planning care for elderly people). Oslo: Elanders, 1997 (in Norwegian). Statens Helsetilsyn (The Norwegian Board of Health). Scenario 2030. Sykdomsutviklingen for eldre fram til 2030. Utredningsserie 699 (Scenario 2030. The development of diseases in elderly people towards 2030. Report 6-99). Oslo: Statens Helsetilsyn, 1999. Paulsen, B. Kalseth B, Karstensen A. 16 prosent av befolkningen-halvparten av sykehusforbruket. Eldres sykehusbruk p 90-tallet (16 per cent of the population half of the consumption of hospital services. The consumption of hospital services in the 90s among elderly people). Oslo: Norsk institutt for sykehusforsking Helsetjenesteforskning. Samdata sykehus Analyse (Norwegian Institute for Hospital Research. Health Service Research), 1999 (in Norwegian). Blstad J. Kronikk: Ingen trenger sykehjemsplass (Chronicle: Nobody needs nursing homes). Dagbladet 1999 Sept 7; 38 (in Norwegian). Statens Helsetilsyn (The Norwegian Board of Health). Tilsynsrapport 1998. Fylkeslegenes felles tilsyn med helsetjenesten for eldre. Oppsummeringsrapport (Supervision report 1998. The regional physicians supervision of the health services for elderly people). Oslo: Statens Helsetilsyn, 1999 (in Norwegian). Hjort P. Fremtiden er lys det er bare tre bekymringer (The future is bright only three problems remain). J Med Assoc Norway 2000; 120: 12 (in Norwegian). Hjort P. Fysisk aktivitet og eldres helse (Physical activity and the health of elderly people). J Med Assoc Norway 2000; 120: 291518 (in Norwegian). Wyller TB. Kvinners helse i Norge. Appendix 8 (Elderly womens health. Appendix 8). Norges Offentlige Utredninger no. 13 (Norwegian public government reports no. 13). Oslo: Statens Trykning, 1999 (in Norwegian). Norwegian Medical Association. Nr du blir gammel og ingen vil ha deg (When you become old and nobody wants you). Oslo: Norwegian Medical Association. Album D. Sykdommers og medisinske spesialiteters prestisje (The prestige of diseases and medical specialties). J Med Assoc Norway 1991; 17: 213336 (in Norwegian). Prioritering p ny- Gjennomgang av retningslinjer for prioriteringer innen norsk helsetjeneste. (Renewing priorities. Going back to the guidelines for prioritisation within the Norwegian Health Service). Norges offentlige utredninger no. 18 (Norwegian public reports no. 18). Oslo: Statens Trykning, 1997 (in Norwegian). Cooper MC. Principle-oriented ethics and the ethics of care: a creative tension. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1991, 14(2): 2231. Udn G, Norberg A, Lindseth A, Marhaug V. Ethical reasoning in nurses and physicians stories about care episodes. J Adv Nurs 1992; 17: 102834. Norberg A, Udn G. Gender differences in moral reasoning among physicians, registered nurses and enrolled nurses engaged in geriatric and surgical care. Nurs Ethics 1995; 2: 23342. Fry S. Toward a theory of nursing ethics. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1989, 11(4): 922. Srlie V, Lindseth A, Udn G, Norberg A. Women physicians narratives about being in ethically difficult care situations in paediatrics. Nurs Ethics 2000; 7: 4762 Lgstrup KE. The ethical demand. (Jensen TI trans 1971; Danish original 1956.) Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1997. Lindseth A. The role of caring in nursing ethics. In: Udn G ed. Quality development in nursing

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

Integrity in the care of elderly people

403

20

21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34

35 36 37

38 39 40 41 42 43 44

care. From practice to science (Linkping Collaborating Centre, health service studies 7.) Linkping: World Health Organization, 1992, 97106. Jansson L, Norberg A. Ethical reasoning among registered nurses experienced in dementia care. Interviews concerning the feeding of severely demented patients. Scand J Caring Sci 1992; 6: 21927. Norberg A, Udn G, Andrn S. Physicians, registered nurses and enrolled nurses stories about ethically difficult episodes in geriatric care. Eur Nurse 1998; 3: 313. Ford MR, Lowery CR. Gender differences in moral reasoning: a comparison of the use of justice and care orientations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 50: 77783. Moody HR. Why dignity in old age matters. J Gerontol Soc Work 1998; 29(23): 1338. Lothian K, Philip I. Maintaining the dignity and autonomy of older people in the health care setting. BMJ 2001; 322: 66870. Lipp A. An enquiry into a combined approach for nursing ethics. Nurs Ethics 1998; 5: 12238. Mishler EG. Research interviewing context and narrative. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986, 5359. Ricoeur P. Interpretation theory: discourse and the surplus of meaning. Fort Worth, TX: Texas Christian University Press, 1976. Ricoeur P. Hermeneutics and the human sciences. (Thompson JB ed, trans; first published 1981.) New YorK: Cambridge University Press, 1988. Ricoeur P. Time and narrative. (Blamey K, Pellauer D trans; first published as Temps et rcit, 1983.) Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1988. Lindseth A, Marhaug V, Norberg A, Udn G. Registered nurses and physicians reflections on their narratives about ethically difficult care episodes. J Adv Nurs 1994; 20: 24550. Sundin K, Axelson A, Jansson L, Norberg A. Suffering from care as expressed in the narratives of former patients in somatic wards. Scand J Caring Sci 2000; 14: 1622. Lgstrup KE. System og Symbol (System and symbol). Kbenhavn: Gyldendal, 1982 (in Danish). Ricoeur P. Critique and conviction. (Blamey K, trans; first published as La critique et la conviction, 1995). Cambridge: Polity Press, 1988. Srlie V. Being in ethically difficult care situations. Narrative interviews with registered nurses and physicians within internal medicine, oncology and paediatrics. (Ume University medical dissertations, new series no. 727) Ume: Ume University, 2001, 4951. Ricoeur P. La mmoire, lhistoire, loubli (The memory, the story, the forgotten). Paris: Seuil, 2000 (in French). Sundstrm P. Sjukvrdens Etiska Grunner (The ethical foundation of health care). Gteborg: Bokfrlaget Daidalos, 1996, 8788 (in Swedish). Lindseth A. The relational ethics of KE Lgstrup what ethics can be and can not be. In Proceedings of: Moral sources and relational ethics: a NorwegianAmerican dialogue on the work of Knud E Lgstrup; 1996 Oct 1819; University of California, San Francisco. Aristotle. The Nicomachean ethics. (Ross D, trans) Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980. Srlie V, Frde R, Lindseth A, Norberg A. Male physicians narratives about being in ethically difficult care situations in paediatrics. Soc Sci Med 2001; 53: 65767. Srlie V, Lindseth A, Frde R, Norberg A. The meaning of being in ethically difficult care situations in pediatrics as narrated by male registered nurses. J Pediatr Nurs 2002 (in press). Lear J. Aristotle: the desire to understand. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. Delholm-Lambertsen B, Maunsbach M. Videnskapsteori og anvendelse (The theory and application of science). Nord Med 1997; 112: 2427. Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative reseach. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1986, 8: 2737. Lantos JD. Do we still need doctors? New York: Routledge, 1997.

Nursing Ethics 2003 10 (4)

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Very Short Introduction To EpistemologyDocument10 paginiA Very Short Introduction To Epistemologyravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- New Notes On ThinkingDocument45 paginiNew Notes On Thinkingravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Intro Philosophy July 2017Document24 paginiIntro Philosophy July 2017ravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- LeibnitzDocument8 paginiLeibnitzravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Unit-Iii: Depth PsychologyDocument10 paginiUnit-Iii: Depth Psychologyravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- 144 Factors Associated With Underweight and Stunting Among Children in Rural Terai of Eastern NepalDocument9 pagini144 Factors Associated With Underweight and Stunting Among Children in Rural Terai of Eastern Nepalravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Attempted Suicides in India: A Comprehensive LookDocument11 paginiAttempted Suicides in India: A Comprehensive Lookravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Unit-Iii: Depth PsychologyDocument10 paginiUnit-Iii: Depth Psychologyravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- 299Document20 pagini299ravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- 869Document22 pagini869ravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Motivations For and Satisfaction With Migration: An Analysis of Migrants To New Delhi, Dhaka, and Islamabad814Document26 paginiMotivations For and Satisfaction With Migration: An Analysis of Migrants To New Delhi, Dhaka, and Islamabad814ravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- SpinozaDocument8 paginiSpinozaravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- 807participation, Representation, and Democracy in Contemporary IndiaDocument20 pagini807participation, Representation, and Democracy in Contemporary Indiaravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Unit-Iii: Depth PsychologyDocument10 paginiUnit-Iii: Depth Psychologyravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- 89.full INDIADocument34 pagini89.full INDIAravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Violence Against Women: Justice System ''Dowry Deaths'' in Andhra Pradesh, India: Response of The CriminalDocument25 paginiViolence Against Women: Justice System ''Dowry Deaths'' in Andhra Pradesh, India: Response of The Criminalravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Transforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive CareDocument17 paginiTransforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive Careravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- A Qualitative Analysis of Ethical Problems Experienced by Physicians and Nurses in Intensive Care Units in TurkeyDocument15 paginiA Qualitative Analysis of Ethical Problems Experienced by Physicians and Nurses in Intensive Care Units in Turkeyravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Culture and Domestic Violence: Transforming Knowledge DevelopmentDocument10 paginiCulture and Domestic Violence: Transforming Knowledge Developmentravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Trends in Understanding and Addressing Domestic ViolenceDocument9 paginiTrends in Understanding and Addressing Domestic Violenceravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Care of The Traumatized Older AdultDocument7 paginiCare of The Traumatized Older Adultravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Visiting Nurses' Situated Ethics: Beyond Care Versus Justice'Document14 paginiVisiting Nurses' Situated Ethics: Beyond Care Versus Justice'ravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Transforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive CareDocument17 paginiTransforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive Careravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Night Terrors: Women's Experiences of (Not) Sleeping Where There Is Domestic ViolenceDocument14 paginiNight Terrors: Women's Experiences of (Not) Sleeping Where There Is Domestic Violenceravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Language Barrier On Acutecaremedical Professionals Is Dependent Upon RoleDocument4 paginiImpact of Language Barrier On Acutecaremedical Professionals Is Dependent Upon Roleravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Ethical Dilemmas Experienced by Nurses in Providing Care For Critically Ill Patients in Intensive Care Units, Medan, IndonesiaDocument9 paginiEthical Dilemmas Experienced by Nurses in Providing Care For Critically Ill Patients in Intensive Care Units, Medan, Indonesiaravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Respecting The Wishes of Patients in Intensive Care UnitsDocument15 paginiRespecting The Wishes of Patients in Intensive Care Unitsravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Transforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive CareDocument17 paginiTransforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive Careravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Meeting Ethical Challenges in Acute Care Work As Narrated by Enrolled NursesDocument10 paginiMeeting Ethical Challenges in Acute Care Work As Narrated by Enrolled Nursesravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- Challenges in End-Of-Life Care in The ICUDocument15 paginiChallenges in End-Of-Life Care in The ICUravibunga4489Încă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Normative Ethics Readings19 20 1Document27 paginiNormative Ethics Readings19 20 1JHUZELL DUMANJOGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compassionate Love As Cornerstone of Servant LeadershipDocument14 paginiCompassionate Love As Cornerstone of Servant LeadershipAnthony PerdueÎncă nu există evaluări

- CSRGOVE Sessions 4 and 5Document71 paginiCSRGOVE Sessions 4 and 5_vanitykÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clair, Joseph - Discerning The Good in The Letters and Sermons of Augustine-Oxford University Press (2016)Document205 paginiClair, Joseph - Discerning The Good in The Letters and Sermons of Augustine-Oxford University Press (2016)FilipeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virtue EthicsDocument13 paginiVirtue EthicsDr. Shipra DikshitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classical Philosophies Specifically Virtue Ethics: Notre Dame of Jaro IncDocument3 paginiClassical Philosophies Specifically Virtue Ethics: Notre Dame of Jaro IncVia Terrado CañedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phillippa Foot - Virtue Ethics (Summary)Document8 paginiPhillippa Foot - Virtue Ethics (Summary)Seed Rock ZooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syllabus Introduction To Philosophy-Roland ApareceDocument5 paginiSyllabus Introduction To Philosophy-Roland ApareceRoland ApareceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Ethics 2 - Moral Reasoning Ethical TheoriesDocument38 paginiBusiness Ethics 2 - Moral Reasoning Ethical TheoriesAhmad Haniff IlmuddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- (MPA-SECTION 20) Key Concepts - Ethics, Accountability, and Public ServiceDocument46 pagini(MPA-SECTION 20) Key Concepts - Ethics, Accountability, and Public ServiceSarah Jane Bautista100% (1)

- Virtue EthicsDocument6 paginiVirtue EthicsTheLight7 Dark6Încă nu există evaluări

- Ge6075 MCQDocument29 paginiGe6075 MCQVishnu53% (15)

- ArticleDocument96 paginiArticlekritim81Încă nu există evaluări

- Business Ethics - Theories and PerspectivesDocument12 paginiBusiness Ethics - Theories and PerspectivesYasheka StevensÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virtue: (Etymologically) Means Manliness, I.E. Strength, Courage A DDocument11 paginiVirtue: (Etymologically) Means Manliness, I.E. Strength, Courage A DAngelyn SamandeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics-Natural LawDocument40 paginiEthics-Natural LawJhianne Mae AlbagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virtue Ethics and Decision Making in Business ManagementDocument4 paginiVirtue Ethics and Decision Making in Business ManagementjazreelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics Activity2Document7 paginiEthics Activity2Anna MutiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 1Document16 paginiQuiz 1bobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics Class, 2nd Semester 2018-2019 Rhea A. CadaoasDocument2 paginiEthics Class, 2nd Semester 2018-2019 Rhea A. Cadaoasjasmine gay pascualÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics NotesDocument99 paginiEthics NotesgowrishhhhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics (2ND)Document4 paginiEthics (2ND)Yna Padilla BiaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aristotle and Virtue Ethics: The Goal of HumanityDocument4 paginiAristotle and Virtue Ethics: The Goal of HumanityGenie IgnacioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment in Ethics About Aristotle Virtue EthicsDocument6 paginiAssignment in Ethics About Aristotle Virtue EthicsFrednixen Bustamante GapoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lintian Na BESR - Docx Ver PutchaDocument39 paginiLintian Na BESR - Docx Ver PutchaAnna Mae Loberio100% (1)

- Chapter 8 Engineering Ethics (Risk, Safety, and Accidents)Document26 paginiChapter 8 Engineering Ethics (Risk, Safety, and Accidents)Shashitharan PonnambalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fred Alford - 2014 - Bauman and LevinasDocument15 paginiFred Alford - 2014 - Bauman and LevinasAndré Luís Mattedi DiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics: The Study of What Is Morally Right and WrongDocument22 paginiEthics: The Study of What Is Morally Right and WrongLyka AcevedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 4: Filipino Values and Moral DevelopmentDocument35 paginiLesson 4: Filipino Values and Moral DevelopmentManiya Dianne ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

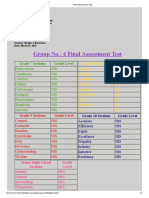

- Final Assessment TestDocument1 paginăFinal Assessment TestKatrina AmoresÎncă nu există evaluări